[Page 120]

The Secret Societies “Nes Tziona” (“Netz”) and “Netsach Yisrael”

Translated by Jerrold Landau, based on an earlier translation by M. Porat z”l that was edited by Judy Feinsilver Montel

The Netzi'v was devoted heart and soul to the “Chovevei Zion” movement, albeit the Yeshiva was the soul of his life. Therefore, he demanded one thing only from his students: to be devoted entirely to Torah study and not to divert their thoughts to other ideas. In one of his letters to the Chovevei Zion Committee in Warsaw, he appologized for not being active in the work for “The holy organization for the settlement of the Land of Israel,” because all his time and energy was dedicated to the holy Yeshiva, of which he was the living spirit, and for which there was nobody else to bear its burden. If the Netzi'v, the Yeshiva's head, could not find any possibility to refer his attention to national activities, all the more so could he not agree that his students interrupt their studies, divert their attention from their efforts in the Yeshiva, and immerse themselves in work for Chibat Zion.

In any case, the national revival ideas penetrated through the Yeshiva walls and were implanted deeply in the students' hearts. The Volozhin Yeshiva became the center of the national movement among the Beis Midrash attendees, from where the idea of Chovevei Zion spread out into the important Torah centers of the Diaspora. A clandestine organization called Nes Tziona was founded in the Yeshiva. There was no other organization like it. The center of the organization was in Volozhin, and its emissaries spread out throughout the country. It conducted a great deal of publicity amongst Torah oriented Jewry for the upbuilding and revival of the Land.

A meeting was held by seven Yeshiva students in utmost discretion during the winter of 5645 [1885]: Moshe Barshak, Ben Zion Dante, Shimon Zlotoybke, Yakov Flakser, Menahem Fridman, Yosef Rozenkrantz and Yosef Rotshtayn. They laid the foundation of “Nes Tziona” [Banner of Zion] Society and pledged allegiance to its aims.

[Page 121]

|

|

Rabbi Yehoshua Heschel Levin

Sitting (right to left): Menachem Fridland, Menachem Mendl Nahumovski, Rabbi Moshe Mordechai Epstein, Yaakov Mordechai Alperin

Standing (right to left): Rabbi Avraham Yaakov Flakser, , Yaakov Mordechai Zingman, Chaim Lerman

(The photo was received from the Russian Zionist Archives,

founded by Aryeh Rafael-Tzenzifer)

|

The goal of the organization was the settlement of the Land of Israel with the purity of holiness and Jewishness, and imbuing good, upright and sublime traits and feelings of charm and honor for everything good, effective, holy and precious to the House of Israel.

During the first year of its existence, the society listed more than fifty members. More members were added from time to time. Everything was conducted in complete secrecy. The organization also grew beyond the bounds of the Yeshiva. Its founders set their goal to educate diligent, faithful workers who would prepare to be dedicated to the movement of the settlement of the Land of Israel throughout their lives, and to accept upon themselves the role of disseminating the idea of the revival of the nation and its return to Zion through all the broad pathways of the nation throughout its Diaspora.

The organization found a broad array of willing human resources among the Yeshiva students. Most were young, and their hearts were alert to everything good and effective taking place in the community and in the nation. In order to protect their organization from the “evil eye,” to secure its existence, to ensure the trustworthiness of its members and to strengthen the connection between them throughout all the days of their lives and to bring them in to the yoke of reality, the founders found no

[Page 122]

other way to ensure proper protection than imposing an oath upon every member as they entered Nes Tziona. The oath consisted of two ideas: faithfulness to the organization, and dedication to work throughout life; and maintaining the secret, so as not to disclose anything that was seen or heard within. The oath was as follows:

“In the name of our Holy Land and in the name of all that is dear and holy to me, I am swearing this oath of allegiance to be faithful to our Society's purposes and to make every effort throughout my life to accomplish the idea of settling the Land of Israel, and to refrain from disclosing anything to anyone until they too enter into the covenant with an oath.”

One of the first activities of the society was to disseminate literature in praise of the settlement of the Land of Israel. The society disseminated the book Doresh Tzion [Inquiring about Zion] by Rabbi Ch. Y. Kramer, published in 5645 [1885], as well as other books. Hamagid and Hameilitz were also distributed by the members. In the year 5649 (1889), members of the society took the initiative of publishing a large anthology on the idea of the settlement of the Land of Israel. The anthology was supposed to include sections from our literature throughout all the generations relevant to the idea of the settlement of the Land of Israel and the love of Zion, aside from sections from the ancient literature, from the Bible, the Mishna, Talmud, and Midrash. Those involved also wanted to include items from the new era starting with Rabbi Kalisher and ending with the rabbis of Chovevei Zion of their generation.

However, the publication of the anthology never took place, because the existence of the society became known to the authorities at the beginning of the year 5650 [1890]. That year, a letter from a member of the society to a student of the University of Dorpat [trans: an old name for Tartu, Estonia], regarding the society in Volozhin was intercepted by the authorities. The police searched the student of the Yeshiva who had sent the letter and found with him the copying machine that printed the flyers. The lad was arrested. This matter disturbed the Netzi'v greatly. He had not known about the existence of the society. They did not do anything against the heads of the society, but the result was the disbandment of the society.

In the winter months of 5651 [1891], a second secret society “Netzach Yisrael” (The Eternity of Israel) was created inside the Yeshiva. Chaim Nachman Bialik played an active role in it. Bialik writes in his “Autobiographical Note”:

“It happened during the publication days of Ahad Ha'am's first articles. The best and the “enlightened” Yeshiva students formed a society and vowed to dedicate their talents and their entire life to working for their people. The foundational idea of the society was indeed glorious. It was stated as follows: The Volozhin Yeshiva is the center of the best talents that will ultimately spread amongst the Jewish world, penetrate to its midst, and be absorbed into it, and become its leaders, as rabbis, doctors, and scholars, as well as administrators, communal heads, publicists and writers. Therefore, it would be sufficient for us to establish among the Volozhin students a permanent incubator for lovers of Zion. These would later turn the entire world into lovers of Zion, etc.

“The society was based on the cream of the crop of Yeshiva students, and of those with clear intellect. Every

[Page 123]

person accepted as a member was tested thoroughly from every side. Only those who were deemed to become a benefit to the cause in the future were chosen as members. I was considered as a future writer (that is how I was known) and this was the reason for my acceptance as a fellow in their company. I was one the first ones. At this very time, I wrote an article, as requested by my colleagues of the society. This was my first literary attempt. It was titled “The Idea of Settlement.” It was published in Hameilitz of that year. That article was intended as a manifest of our society to publish its outlook to the world.”[38]

What aroused the enlightened students in the Yeshiva to found the society? There is a theory that the chief factor in this was the article of Ahad Ha'am “The Priests and the Nation.” In it, it is written that “Any new idea, whether religions, traditional, or social, will not stand and will not come to be unless there is a group of priests who will dedicate their lives to it, and work on it with their whole heart and whole personality.”

The purpose of the organization was: “The settlement of the Land of Israel with the purity of holiness.” The meaning of “purity of holiness” is not only the upkeep of the religion in its simple meaning, but also complete traditional renewal, rooted in all the praiseworthy traits of Judaism within the Hebrew nation. The settlement in the Land must be a national home in the traditional Jewish sense, to serve as a center for Jews and Judaism.

There were some twenty members who composed the Society. Despite their small number, they considered each activity as very important. They planned to establish a cooperative settlement for religious youth in the Land of Israel, which would be a showpiece not only of loving work but also of morality and religious ethics. An important letter remains from M. L. Lilienblum to Bialik and his friends, dated 3 Sivan 5651 [1891], in which he informs them that he received their letter: “May G-d, the L-rd of Zion, be with the mouths of the Jewish lads, and grant them grace and mercy before the philanthropist, to have mercy upon them and upon our Land.” He blessed the writer of the letter, Bialik, with: “With all my heart that his good intentions become actualized.”

The Yeshivah was closed in the winter of 5662 (1892). The students dispersed and that was the end of that society in Volozhin[39].

Original Footnotes:

- Ch. N. Bialik: “Autobiographical Notes” Knesset, Book VI, Tel Aviv, 5701 [1941], page 15. Return

- A. Droyanov published in “Writings on the History of Chibat Zion and the settlement of the Land of Israel” Volume II, pp. 797-799, a letter from “A group of students of the Volozhin Yeshiva” to K. Z. Wissotzki from the year 5649 [1889] regarding designating a plot of land for the founding of an agricultural settlement in the Land of Israel for students of the Volozhin Yeshiva. The letter is as follows: “The national movement is continually spreading throughout our brethren the House of Israel. Great is the commandment of actualizing the settlement of our Land, for the time of its mercy has come. The bitter situation of our brethren and their bad lot in their lands of dispersion also breathed into our hearts the idea of making aliya to Zion, of working its land, eating of its fruits, and satiating ourselves with its goodness. Approximately 100 people have forged a covenant and formed a society for the founding, with G-d's help, of a settlement in our Holy Land, so we can be tenders of vineyards and farmers upon the mountains of Israel. It has been acquired for us from our brethren, men of valor, who went out as pioneers and made aliya to Rishon Letzion to till its mountains and smooth outs its valleys. Their hope for the future, with the vine plantation, is that it shall blossom and bear fruit.”

Later, they request from Wissotzky that he “Purchase the necessary land for our desire, stating that they are prepared to provide 5,000 rubles as an advanced payment, so that he would perhaps agree to give over the land, and they would pay interest according to an agreement.”

The signatories: Reuven the son of Rabbi Dov Yaakov HaKohen Gordon, Eliyahu Aharon Milikowsky, Menachem the son of Tzvi Krakowski, Yaakov the son Rabbi Baruch Yosef Blidstein, Shalom Eliezer the son of Rabbi Y. Rogozin (or Rogovin), Yeshayahu Bunimowitz, Aharon Yaakov Perlman, Efraim Zamonov (the grandson of the Netzi'v, the husband of the daughter of Rabbi Chaim Berlin), Moshe Chaim… Yitzchak Yaakov Perski. Return

[Page 124]

The Dispute Between the Netzi'v and Rabbi Yosef Dov Soloveitchik

Translated by Jerrold Landau based on an earlier translation by M. Porat z”l

A leadership of pairs, consisting of the Yeshiva head and his deputy, has always been in effect at the Etz Chaim Yeshiva. During the era of Rabbi Itsele, his son-in-law Rabbi Eliezer Yitzchak served as his deputy. After Rabbi Itsele's death, Rabbi Eliezer Yitzchak served as the Yeshiva head, and the Netzi'v was his deputy. The Netzi'v was appointed as Yeshiva head after the death of Rabbi Eliezer Yitzchak. Rabbi Yosef Dov Soloveitchik, a great grandson of rabbi Chaim Volozhin through his daughter, was appointed as his deputy. It is written in the writ of rabbinate given to the Netzi'v: “And as his deputy, we have chosen to place the honor of the great, sharp, famous rabbi, Rabbi Yosef DovBer the son of Rabbi Yitzchak Zev HaLevi, a grandson of the Gaon, our teacher Rabbi Chaim, may the memory of the holy be blessed, to assist and support the aforementioned Yeshiva head by teaching halacha to the students – for he is good and effective in imparting his didactics [pilpul] to the students.”

These two Gaonim had different opinions as to the methods of Talmud learning. The Netziv's son, rabbi Meir Berlin, describes the methodology of the Netzi'v:

“The Volozhin Yeshiva introduced the method of study that can be traced to the Gaon of Vilna. Through this, the students of this Yeshiva differ from those who learned their Torah from other Yeshivas. This method of study is not based on sharp didactics, sectional expertise, or exactitude of wording. Rather, it penetrates into the Talmudic discussion and everything stemming from it. The aspiration for truth, efforts in preparation, and the will to understand the clear meaning – that is the learning methodology of the Rabbi of Israel (the Netzi'v) in his books, and that was the learning methodology of his Yeshiva and his students. The first approach is toward understanding and depth. To determine whether the understanding is correct, or whether the digging in depth is distorted, one must find support in the words of the great early sages, and especially from Talmudic sections that deal with the same concept in general, for there are cases where words of Torah are poor in one place, but rich in another place.”[40]

The Netzi'v fundamentally rejected pilpul, stating that “Just as it is impossible to discharge one's obligation of a set meal through delicacies and sweets alone, even if they are good and proper when they follow a full meal with bread, fish, and meat – similarly, sharp pilpul is good if it comes as

[Page 125]

accessories and sweet treats,” after the set study of Talmud, decisors, and books of the early commentators, after the student reaches the level of complete, true acquisition of the fundamental treasures and virtues of the Torah.

In the eyes of the Netzi'v, Torah study alone was important. And the more a man increased his Torah knowledge the more his spiritual power would grow. The Netzi'v would explain the matter with a parable from life: A studier can be compared to a machine in a factory. As long as you add coals for fuel, it works with greater diligence and complete purpose, and produces proper products. This is not the case of a meager quantity of coals are provided. The machine will then function lazily, without the spirit of life, and the products it produces will be without form or glory.

Such is also the complete man who has acquired his Torah. The more Torah he acquires from Talmud, decisors, and the books of the early commentators – for all of these demonstrate the clear fundamental of every law and area of research, like coals in a machine – the more he will be able to research and answer every Torah matter that comes his way. He will find the sources and basis in his Torah that he has studied in breadth and depth.

For this reason, the Netzi'v did not look positively at those who elongated their prayers, for overly extended praying interferes with the study of Torah. Torah learning demands that the student be dedicated to it totally and at all times. Regarding this, the Netzi'v relates that during the times of Rabbi Chaim of Volozhin, a certain scholar studied in the Yeshiva, and took a great deal of his time from his studies to recite Psalms. Rabbi Chaim was pained that his student took away so many hours from the study of Torah, and he reproved him for this. His student told him: “Our rabbi, indeed, it says in the agada [Talmudic lore] that King David requested that everyone who occupies himself with the recitation of Psalms will be considered as if he is occupied with [the laws of] leprous legions and [impurity transmitted by] coverings.” Rabbi Chaim responded: “It is indeed true that he requested, but we do not know how the matter was answered to him.”

Rabbi Baruch Halevi Epstein describes the essence of the controversy between the Netzi'v and Rabbi Yosi Ber Soloveitchik in the following words:[41]

“As opposed to the Netzi'v, the Gaon Rabbi Yosi Ber considered sharp pilpul to be a precious tool to forge the young students' intellects, to sharpen their logic, and thereby to excite the rivalry of wisdom and to make them enjoy the competition.

The two methodologies, or two regimens, at opposite sides gave rise to a chasm between the Yeshiva students. Some followed the opinion and regime of my uncle (the Netzi'v) and revered his methodology as a true and sure path in the ways of Torah, and others enjoyed the path of sharpness of Rabbi Yosi Ber.

At first, the chasm was mild and light, and was only hidden in the hearts of those sages, the mighty ones of their methodologies and paths. However, after the chasm broadened and entered the public domain of the Yeshiva students, it was no longer possible to confine the winds in the hearts of these youths, each of whom, with the heat of their souls and emotions, attempted to prove the superiority of their leanings, methodologies, and pathways that they had chosen

[Page 126]

Slowly but surely, the question turned into a dispute, and the logic became a conflict. Those close to each other grew apart; friends became ideological adversaries. It had become a storm of tribulations. Furthermore, as time passed, the dispute broke forth from the confines of the walls of the Yeshiva, and moved on to towns near and far from Volozhin. Several students and Torah giants began to take interest in the difference of opinion.”

To settle the controversy, four of the Torah greats of the generation were summoned to Volozhin: David Tevel, the head of the rabbinical court of Minsk, Rabbi Yosef from Slutsk, Rabbi Yitzchak Elchanan from Kovno, and Rabbi Zev Landau the preacher from Vilna. They were joined by the wealthy Rabbi Yehoshua Levin of Minsk.[42]

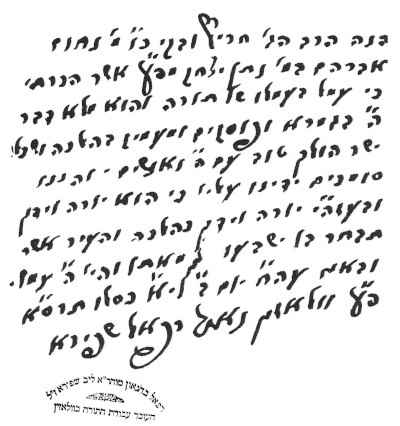

The following was their verdict from 4 Cheshvan, 5618 (1857):

“When we came together and gathered here in the holy community of Volozhin to investigate the issues of the great house in which Torah is nurtured for the masses by our rabbi and teacher, Rabbi Naftali Tzvi Yehuda, may his light shine, and our rabbi and teacher, Rabbi Yosef Dov, may his light shine – the following is what we the undersigned agreed and have recorded.

- First of all, we decree that there should be peace between the rabbis, and that any Yeshiva student who impinges upon the honor of one of the aforementioned rabbis, and the matter becomes known, both of them must distance him or punish him as they see fit.

- The accepting of students into the Yeshiva is dependent on the will of Rabbi Naftali Tzvi Yehuda, as it was until now. Only when a letter arrives specifically to Rabbi Yosef DovBer does he have the rights to accept him on his own.”

[Page 127]

After the verdict, Rabbi Yosi Ber did not see a place for himself in the Yeshiva. He left it and accepted a rabbinical post in Slutsk. Rabbi Rafael Shapiro, a son-in-law of the Netzi'v, took his place. Despite this, the two great ones of the generation forged bonds of marriage between themselves. Rabbi Chaim Soloveitchik, the son of Rabbi Yosi Ber, married the granddaughter of the Netzi'v, the daughter of Rabbi Rafael Shapira.[43]

Original Footnotes:

- Rabban Shel Yisrael, page 106. Return

- Mekor Baruch, Section IV, chapter 37, “Between Holy and Holy” page 1694. Return

- Rabbi Yaakov Halevi Lifschitz writes about the difference between the Netzi'v and Rabbi Yosi Ber, as well as the impression that the arrival of the delegation had on the Yeshiva students: “These holy Gaonim and Tzadikim were different from each other in the traits of their souls and their methodologies of study and delving into Torah, as well as their paths of life. Since they were different from each other, and could not agree on the methods of conducting the Yeshiva and methodologies of study, a dispute broke out regarding who was better in behavior.” (Toldot Yitzchak, chapter 16, Orach Latzadik, page 58). He writes about the delegation: “Regarding the controversy between the two Gaonim, heads of the Yeshiva of Volozhin, that caused a great breach among their students, a difference of opinion among the supporters of the holy Yeshiva throughout the country, a division in ideology – the great Gaonim of the generation called for an increase of peace among the scholars, who increase peace in the world, with advice of peace and truth, advice that they would deliver with their love of truth and peace. They would calm the opinions of the entire community. Are these not the chief Gaonim of that generation, Rabbi David Tevel of Minsk, the author of Responsa Beit David; Rabbi Yosef Behmer of Slutsk; the famous preacher of righteousness, our rabbi and teacher Rabbi Zeev, may the memory of the righteous be blessed, of Vilna; and Rabbi Yitzchak Elchanan – to whom the Netzi'v of blessed memory traveled himself to visit in Novhorodok to request that he come to Volozhin to be counted among the elders of those Torah scholars in expressing his opinion, with holy awe and splendorous honor that no person can describe other than a person who has previously seen the honor of Torah in Israel. All the students of the Yeshiva with their variegated opinions, many of whom were wholesome in Torah and effectiveness, rejoiced and trembled. Some were sharp in wisdom and exacting in halacha, and later became luminaries among the Jewish people. All of them rejoiced and trembled upon the arrival of these great rabbis of Israel who had gathered together.” (Toldot Yitzchak, chapter 17, “In the Council of the Righteous,” pp. 61,62. Return

- See my article in the chapter “Sages of Volozhin” regarding Rabbi Yosi Ber and his son Rabbi Chaim Soloveitchik. Return

Slander Oppresses the Netzi'v

Translated by Jerrold Landau

In the year 5639 [1879], a very difficult event took place in the Yeshiva, which grieved the heart of the Netzi'v greatly. One of the Yeshiva students gave over a bad report regarding the Netzi'v to the Russian authorities. This slander shook the foundation of the Yeshiva, and its echo spread afar.

I'sh Yemin'i writes the following in Hameilitz[44]:

“At noontime, many army men and captains in official uniforms and medals of excellence came to the quiet city of Volozhin. They set out for the sanctuary of Torah, and those who dwelled therein. Th army men surrounded the building, and the ministers (captains) entered. A deathly pall fell upon the faces of the shepherds and their flock. The captains searched all corners of the building, through all the crates and closets, through all the utensils. They confiscated anything they wanted. The took letters, and ledgers of income and expenditures from previous years, and placed them in a crate. They closed and locked it, and placed a government seal upon it, and sent it to the capital city. Only the money they did not take, although they checked the paper bank notes carefully to see if they were forged. When they finished their work, they interrogated the elderly Gaon: Why do you send emissaries to all ends of the earth to collect a great fortune? For what purpose is it designated? Is this done at the behest of the government? – and other such questions. After the interrogation, the minister took out a letter, turned to the rabbi, and asked him: “Do you recognize this signature? Is it your handwriting?” At first the rabbi answered him, ‘It is my signature and handwriting.’ But then he regretted his words and said, ‘It is not my handwriting. In truth it is similar.’ He did not understand everything that was written in the letter. All the responses of the rabbi were recorded in a notebook.”

The government emissaries left the Yeshiva and went to obtain testimony from the officials and Volozhin police chief regarding the activities of the Netzi'v. They responded unanimously that the Netzi'v is faithful to his country and king, and dedicates his days only to Torah. The went to summon the Netzi'v. They received him with great honor and showed him the letter again. The Netzi'v, who had somewhat calmed down from the search in the Yeshiva, looked again at the letter, and then realized to his great astonishment that the letter was forged. Some forger who had signed the letter with a forged signature of the Netzi'v, wrote

[Page 128]

a letter to Rabbi Yaakov Reinovich in London in the name of the Netzi'v, and sealed it with the stamp of the yeshiva. Apparently, the scoundrel knew that the Netzi'v maintained a correspondence with him regarding halachic questions and responsa. The contact of the letter was that the Netzi'v wrote that he had received a letter from Rabbi Reinovich along with 30,000 rubles, one third of which was given to the Yeshiva people, and a second third as a bribe to the judges and police of Volozhin so that they will remain silent, and the final third given to the ministers of the country so that they would avert their eyes from the deeds of the heads of the authorities in Volozhin. The letter further stated that the Netzi'v requested that Rabbi Reinovich send him forged bank notes. It also contained other similar falsehoods.

The Netzi'v came out clean in the judgement, for the investigators were convinced of his innocence. The Netzi'v suspected three Yeshiva students, one from Volozhin, one from Minsk, and one from Vilna, whom the Netzi'v had distanced from the Yeshiva.

The issue of the libel greatly stirred up Erez, the editor of Hameilitz. Among other things, he wrote the following in his article “The Rotating Sword”[45] [i]:

“We have seen enough of this, that a Jewish person was so brazen as to forge a letter in the name of a great rabbi in Israel, elderly, and occupied with Torah, and to attribute to him slanderous words that stir up the heart, and could easily affect the refined soul of the rabbi, who holds back from issues of this world, and could, Heaven forbid, snuff out the wick of his life. The slanderer himself informed the ministers of the state to pay attention to that letter. No sufficient words exist to express all the feelings of our spirit regarding such a terrible travesty.”

Original Footnotes:

- 3 Tammuz, 5639 (June 12, 1879). Return

- Mekor Baruch, Section IV, chapter 37, “Between Holy and Holy” page 1694. Return

Translator's Footnote

- Based on Genesis 3:24. Return

Rabbi Yehoshua Heschel Levin's Rebellion

Translated by Jerrold Landau based on an earlier translation by M. Porat z”l

Rabbi Eliyahu Zalman, Rabbi Itsele's son, married off his daughter to Rabbi Yehoshua Heschel Levin, a grandson of the Maharsh'a (Our Teacher Rabbi Shmuel Eidels)[45a]. Rabbi Itsele was very pleased with him. He would say “This grandson shall have an inheritance in the Yeshiva along with my sons-in-law.”

Rabbi Yehoshua Heschel was very pretentious. He used to say that since he was a descendent of the Maharsh'a, he deserved to become president of the Yeshiva. There was no peace between him and the Netzi'v and Rabbi Eliezer Yitzchak Fried. Things reached the point that Rabbi Yehoshua Heschel stopped visiting the Yeshiva, and set his regular place of worship in the Beis Midrash. Finally, he organized a minyan [prayer quorum] in his home. From then, he completely cut off his connection with the Yeshiva.

Word spread in Volozhin that Rabbi Yehoshua Heschel had started to give classes to those who came to worship at his house, and that the number of attendees continued to grow. Among them were students of the Yeshiva.

[Page 129]

Indeed, this was not a false rumor. Rabbi Yehoshua Heschel decided to forcefully remove the reins of leadership from the Netzi'v and Rabbi Eliezer Yitzchak, and to take the presidency for himself.

In order to attract students, he began to give Talmud classes in his home every morning. Between Mincha and Maariv, he would teach a chapter of Bible with the commentary of Mendelsohn.

|

|

| Rabbi Yehoshua Heschel Levin

|

These classes aroused great interest among the Yeshiva students. They were greatly impressed by them. The number of attendees grew from day to day.

One night, a secret meeting took place in the home of Rabbi Yehoshua Heschel, with the participation of many of the Yeshiva students. At that meeting, Rabbi Yehoshua Heschel announced in public that the crown of Yeshiva head would come to him because he was a grandson of the Maharsh'a. On the spot, a detailed plan was hatched to began preparations for a transfer of the presidency of the Yeshiva.

The lads who participated in the meeting aroused a great tumult in the Yeshiva. This reached the point of an open revolt against the Netzi'v. The community of Volozhin was shaken up by this commotion, which placed the existence of the Yeshiva in danger. The communal heads called a meeting in the Beis Midrash in order to deliberate about what to do.

The matter reached the communal heads in Vilna and Minsk. Rabbi Yehoshua Heschel received a letter from Vilna, signed by several gabbaim, advising him, for his own good, to cease thinking about the presidency of the Yeshiva of Volozhin, for his glory would not come through that path.

One day, when those close to Rabbi Yehoshua Heschel gathered in his home for the shacharit service, they did not find him at home. He left Volozhin in haste, and set out in an unknown direction.

A legend spread through Volozhin that Rabbi Chaim of Volozhin appeared to Rabbi Yehoshua Heschel in a dream, and commanded him to leave the city quickly, for his actions were liable, Heaven forbid to destroy the Etz Chaim Yeshiva. Thus ended the revolt, which threatened to uproot the Yeshiva.

Original Footnote:

- Rabbi Yehoshua Heschel Levin was born in Vilna on 18 Tammuz 5578 (1817) to his father Rabbi Eliyahu Zev. In the year 5631, he was appointed as the rabbi of the Warsaw suburb of Praga, where he served for one year. At the end of his life, he served as the rabbi of the great Beis Midrash of the Jews of Russia and Poland in Paris. He died there on 15 Cheshvan, 5644 [1884]. Books that he authored include: “Glosses on Midrash Rabba,” Aliyat Eliyahu (history of the Gr'a), Maayanei Yehoshua, Tziun Yehoshua, Tosafot Tzion, Pleitat Sofrim, and Dvar Beito. Return

The Moral Sublimity and Educational Excellence of the Netzi'v

Translated by Jerrold Landau based on an earlier translation by M. Porat z”l

On the eve of Shavuot, 5645 (1885), an event took place in the Yeshiva in which the Netzi'v was revealed as an exemplary moral-educational personality. During that period, the Yeshiva excelled with many prodigious students. However, the mashgichim [religious supervisors] began to look into them and to suspect that they were not fulfilling the commandment of public worship appropriately, and that many of them are failing to come for the Yeshiva for the Shacharit service. In order to suppress this “plague,” the Netzi'v nominated a special supervisor to serve as vice principal. His official role

[Page 130]

was to oversee the Yeshiva library, and to give the students the required Gemara volumes. Secretly, however, his job was to investigate the deeds and behavior of the Yeshiva students outside the walls of the Yeshiva. The Netzi'v gave this role to a certain zealot, who would bring the bad reports of the students to the Yeshiva head. The students hated this man with a strong hatred. They nurtured their enmity, and waited for the day when they would be able to take their revenge.

On the morning of that Shavuot eve, this spy informed that many of the Yeshiva students cut their peyos when they took their haircuts on the Shloshet Yemei Hagbalah[i], when haircuts were permitted. The prayer service passed peacefully until the end of the Shmone Esrei prayer. However, at its conclusion, the Netzi'v began to circulate among the students, directing an angry stare at them. He withheld his anger, and did not touch any student during the time of prayer, les the head tefillin be displaced and fall due to the slap, leading to a desecration of the holy object.

At the conclusion of the services, the Netzi'v delivered his class on the weekly Torah portion, as was his custom. When he concluded his class and left the Yeshiva, he met along the way a prominent, well-known student, who was very diligent and consistent in his studies, and was also one of the wealthy ones. He was returning from his residence with a Gemara in his hands. He had bathed, and his peyos were completely cut off. He had not worshipped in the Yeshiva that day, and knew nothing at all of the “hunt” for peyos that the Netzi'v had conducted. When the Netzi'v saw him, he poured out all his concealed wrath at him, and even hit the student. The student was astonished and surprised, as he did not know what this was about. The Gemara fell to the ground, and he stood there beaten, and shocked from the great shame.

This deed caused a storm among all the Yeshiva students, who decided to take revenge for the embarrassment of their friend. When the students took their places and began to study, they began to bang the tabletops incessantly. This served as a sign for the beginning of the revolt. All the students sat in their places studying, while their hands rose and fell upon the shelves of the learning tables. In addition, all the windows were open wide. The wind came through, and the windowpanes shattered.

The vice principal entered during the revolt. His appearance was like fire to wood. The banging grew stronger. Four Yeshiva students rose from their places, approached him, and said, “Get out of here, you scoundrel and slanderer! From this day on, do not dare to cross the threshold of the Yeshiva, for your end will be bitter.” They did not suffice themselves with this warning. They lifted him with their arms, placed him on their shoulders, and forcibly removed him from the Yeshiva.

At noontime, the Netzi'v came to the Yeshiva, as usual, to deliver his lesson. However, the students did not extend honor to their rabbi, and the tumult grew even stronger. He banged his hand on the small table many times, but it was for naught, as nobody listened to him. The Netzi'v circled the hall numerous times and asked the students to calm down, but to no avail. Angry and bitter, the Netzi'v left the Yeshiva without completing his class.

The time for the Mincha service approached. All the students came to the Yeshiva dressed in festive garb. The Netzi'v

[Page 131]

arrived and the service began. They recited the silent Shmone Esrei as if nothing had happened. However, when the prayer leader reached the word kadosh in the kedusha, the students pronounced the sh sound for a long time, until it sounded like an uninterrupted sound: sh sh sh. Furthermore, many students tossed onions and potatoes into the women's gallery.

On every Sabbath and festival, when things functioned normally, the students would approach the Netzi'v one by one after the services to wish him “Gut Yom Tov, Rabbi.” However, when the service concluded that Shavuot eve, they did not move from their places, and stood as if mute. Silence pervaded in the Yeshiva hall.

When the Netzi'v saw all this, he decided to put the cure before the affliction, and began to shout out many times, one after another, “Gut Yom Tov, children!” However, the students stood silent, and did not return the greeting. The Netzi'v realized the extent of the stubbornness of the students, and the extent to which they were continuing with their revolt. He was afraid and perplexed lest this revolt lead to a neglect of Torah study on that Shavuot night, for on Shavuot, the Yeshiva students were accustomed to study all night. He sought a way to put an end to this terrible revolt, the likes of which had not taken place in the Yeshiva since the day of its founding.

He felt that this time, the students would not give in. A deep battle broke out in his heart, a battle between the love of Torah and his own conscience. This internal battle lasted several moments, until the love of Torah won out, and he submitted.

He banged his small table several times and said: “Wait, do not leave until you listen to my words!” He ascended the bima, and, with a frightened voice, began to deliver a lecture on the events of the day. The content of his lecture was that the students must also forgive the rabbi. He felt that he had erred. He begged forgiveness and pardon from the beaten student in the presence of the entire congregation. “Forgive my sin,” he called out at the end, “Even though it is grievous.” When he finished his words, the pillars of the Yeshiva shook from the voices of the students, calling out “Gut Yom Tov, Rabbi!”

Through this act of begging for forgiveness, the Netzi'v rose to a very great height as a great pedagogue, and a man of wonderful morality.

Translator's Footnote

- Literally “three days of setting boundaries” – referring to the virtual boundaries set around Mount Sinai prior to the giving of the Torah, to prevent the people from ascending the mountain. This is a term for the three-day period of preparation prior to Shavuot. The time period is considered as festive in anticipation of Shavuot. Haircutting, forbidden during the Omer period, are permitted by all customs (customs vary as to the portion of the Omer period during which some mourning observances apply). Return

The Big Uprising at the Yeshiva

Translated by Jerrold Landau, based on an earlier translation by M. Porat z”l

In the last years of the Yeshiva's existence the Netzi'v felt his energy leaving him, and he was no longer able to deliver his class. Therefore, he decided to pass the mantle of Yeshiva leadership to his son, Rabbi Chaim Berlin. This decision aroused a great tumult in the Yeshiva, for the students claimed that the son's power was not like his father's.

This is how Abba Blusher described the uprising in his article “Bialik in Volozhin”[46]

“That year (that is, the final year of the existence of the Yeshiva), was a year of tumult in the Yeshiva, due to the desire of the Netzi'v to install his oldest son into his position.

[Page 132]

“The Yeshiva students were opposed to this, for the power of the son was not like the power of the father. This internal battle was difficult and stubborn from both sides. The weapons of the Netzi'v in this battle were tears and pleas, and the weapons of the students were their voices and hands. The voice was the voice of Jacob, angry and shouting, going from one end of the world to the other. The hands were the hands of Jacob. They too threw arrows and catapulted stones from behind the fence, from where their owners could see but not be seen.

“The Netzi'v received anonymous letters every day and every hour. Most were written with coarse hands, full of words as hard as sinews against him, impinging on his honor in a coarse manner, like the frogs of Egypt. In this manner, letters reached the Netzi'v in his bedroom and upon his bed, at the Holy Ark, at his podium, in his tallis bag, between the pages of his books and in the pockets of his clothing. There was no place devoid of them. The Yeshiva students followed after the footsteps of the old man, watching every step, in a cruel manner that only the youth could do, causing him great suffering.

“The image of the Yeshiva diminished during this time of emergency. His daily regimen was affected, and his supervision was weakened. The serious students left the Yeshiva and moved to the small Beis Midrashes in the city or convened together in their rooms with their Gemaras. Prisoners of the war circulated around the markets and the roads. They went from home to home and occupied themselves with politics.

“The Zhitomerer (that is Bialik) was not among the fighters, and certainly not among the prisoners of war, even though he too agreed that the words emanating from the Netzi'v, to impose his will upon the Yeshiva against the will of the students, was an error. He was angry about the disgrace that the Yeshiva students were casting upon their dear rabbi. He castigated the tactics of battle that they utilized. Nevertheless, he gave his share to the battle in the Yeshiva. He sat and wrote an anonymous letter to the Netzi'v. A messenger placed it in the podium of the Netzi'v It was related in the Yeshiva that when the Netzi'v read this letter, which was written in fine style, with politeness and respect, he enjoyed it greatly. This letter remained on his table. He would boast to guests that came to visit him, saying, 'See how they write Hebrew in the Volozhin Yeshiva.'”

Chaim Nachman Bialik writes about the uprising in the Yeshiva in his poem “On the Night of Uproar,” in the following words:

Then, the Yeshiva turned to a den of wild ones

The armies of G-d fought with an outpouring of wrath

Hidden powers broke forth like a strong wind…

A hundred hands released the chains

Suppressed anger was set free

They shattered windows, extinguished candles

And overturned benches and tables.” |

[Page 133]

Bialik himself did not interrupt his studies and did not participate in the battle. Rather, he continued to study with the light of the one candle that remained. The students were wreaking havoc and the Netzi'v protected them with his body:

“However, one candle remained in the corner

Even the wind did not dare to extinguish it.

It occupied a space of two cubits, protecting the Divine Presence

And her precious sons – may G-d protect it.

“That was the place of our relative, the lad, and regarding him

Full of mercy and grace, like a father to his only child,

Like an eagle to its nest, to its surviving chicks.

The pillaged ones – thus did the rabbi show concern for his student.”; |

With great faith, Bialik describes the great tragedy of the Netzi'v:

“Suddenly the old man rose up

And raised his lean hand and touched the shoulder

Of the thoughtful lad, and tears flowed like a stream

They flowed between the silver threads…

The shocked youngster turned his head

The lad was shocked, and he turned his head.

Ho, my teacher and rabbi! – Aha, my dear son

And the boy's eyes rose up to his teachers eyes

Like a child's to his father's.

“Had you seen what they've done, oh lad…?

They did not honor my age, they did not respect me…

They swallowed my holy things, they violated my sanctuary

For which I dedicated my life, my interest.

But you – the eyes of the old man penetrated

Stared at the lad and forever

He will not forget the penetrating gaze of his teacher

Penetrating to the soul of the pure lad.”[47] |

Bialik reacted to the uprising of the large majority of the students with such reverence, forgiveness, and love.

Original Footnotes

- Meoznaim, volume IV, booklet II (20). Tammuz 5695 (1935) Return

- Chaim Nachman Bialik: “On the Night of Uproar” (A passage extracted from Hamatmid), Knesset, Dvir Publishing, Tel Aviv 5696 (1936), Book I, from Bialik's estate, pp. 4-8. Return

The Netzi'v is Saddened in his Heart

Translated by Jerrold Landau

The uprisings in the Yeshiva, particularly the one that broke out regarding the desire of the Yeshiva students to appoint Rabbi Chaim Soloveitchik as the Yeshiva head and to reject Rabbi Chaim Berlin for that position, depressed the spirit of the Netzi'v, which was in any case in a poor state due to his illness.

This is how Menachem Mendel HaLevi Ish-Horowitz, a student of the Yeshiva, describes the Netzi'v during those days[48]:

“And the Yeshiva head sat on a chair at the Eastern Wall, leaning his head and immersed in his thoughts. He was thinking various thoughts, worried about various concerns, and also hoping positive hopes. Everything that took place with him in his prime, the good as well as the bad, the toil and tribulations, was passing before him like sheep, event after event. What were the years of his live? Like twenty-five years. Immediately after his marriage, he studied Torah himself

[Page 134]

closed in a room in the “Ezrat Nashim” home, day and night without end. He never saw the day of light and knew no rest. This was his only rest and purpose. However, this made it possible to make a name for himself and to raise up many students – 20,000 or more. Was this not the entire life of his spirit and goal of his soul. He still remembers everything that happened to him in the home and outside: the hatred of his father-in-law's in-laws for him during his youth, when he was devoted to Torah study and did not turn to any worldly pleasures, and he was the source of half of their mockery. Then there were the tribulations of all the Yeshiva students, who surrounded him and circled him at all hours. Over and above all those, there were the edicts and decrees of the government, and the inquiries regarding the holy Yeshiva. This was over and above the yoke of many debts that surrounded his neck, and continually increased.

“With these thoughts, the cold deepened and saddened his heart. However, there was still a hope in the recesses of his heart, that his son would rule after him, and sit on his throne. Perhaps he would rectify the wrongs, even if the Yeshiva students do not accept the yoke of his awe and love. But, but… A few more days passed, several months passed… And he became elderly. His last day was perhaps approaching. Did he not accomplish a great deal during the years of his life. He pondered and pondered, and perhaps dozed off a bit. Without intention, he awoke and set his gaze upon the images of the Yeshiva building. It was already late, and the time for the Maariv service arrived. 'The wicked shall return to questioning' – he banged on the podium, all conversations stopped at the sound of Vehu Rachum[i] emanating from the prayer leader.”

Original Footnote

- Derech Etz Hachaim, pp. 103-104 Return

Translator's Footnote:

- The opening words of the weekday Maariv service. Return

The Pinnacle Years of the Yeshiva

Translated by Jerrold Landau

The Yeshiva reached its pinnacle during the final years before its closing, both with respect to the number of students, as well as the level of talent of the students who studied there. Among the students who studied there were some of brilliant talents, who later appeared in Jewish life in Russia, and disseminated their Torah and wisdom, each one in his place of residence. These included: Rabbi Chaim Ozer Grodzinski, the Illuy [genius] of Iwye, who later became famous as one of the great ones of his generation; Rabbi Avraham Yitzchak HaKohen Kook, whom the Netzi'v loved very much, and called “My Avraham Itze”; Rabbi Moshe Mordechai Epstein, the Illuy of Baksht, who later served as the head of the Knesset Yisrael Yeshiva in Slobodka and later in Hebron; Zunia Mirer (that is what the Illuy of Mir was called in Volozhin), who studied in Volozhin for about seven years, was a friend of Rabbi Chaim Soloveitchik, and later became known as the Gaon Isser Zalman Meltzer, the rabbi in Slutsk and later the head of a Yeshiva in Jerusalem and the author of novellae on the Ramba'm; Beril Kobriner, the Illuy of Kobrin, who later became known as the Gaon Rabbi Avraham Dov Ber Shapira, the final rabbi of Kovno; Rabbi Baruch Berl, who later became the head of Yeshivat Knesset Beit Yitzchak in Slobodka, and continued in the methodology of his rabbi, Rabbi Chaim, with great exactitude, and authored deep books. Shimon of Turitz, who was the famous Gaon Rabbi Shimon Shkop, one of the

[Page 135]

great Yeshiva heads in Telz; Menachem Krakovski from Volkovisk, who later served as a rabbi in Novogrudek, and a preacher in Vilna. He authored a book called Avodat Hamelech on Sefer Hamada of the Ramba'm, written in a scientific fashion, which was a great innovation in rabbinical literature; Baruch of Lomza, who served as a rabbi in Krynki. He authored the book Minchat Baruch and became known as one of the great ones of the generation; Rabbi Moshe David, the Illuy of Utian [Utena], who later became the son-in-law of the Rogochover Gaon; Rabbi Shlomo of Maytchet, who later became famous in all the Yeshivas as the Illuy of Maytchet. He was brought to Volozhin at the age of twelve, celebrated his Bar Mitzvah in the home of Rabbi Chaim Soloveitchik, and delivered a lecture with sharp didactics [pilpul]; and finally – Chaim Nachman Bialik, the poet of the nation.

The Authorities Persecute the Yeshiva

Translated by Jerrold Landau, based on an earlier translation by M. Porat z”l

External troubles were added to the internal problems and disorder within the Yeshiva. The Czarist government authorities continually increased the pressure upon the Yeshiva. From the beginning of its existence, the Yeshiva was like a thorn in the eyes of the Russian government. As long as the mighty spiritual fortress known as the Etz Chaim Yeshiva existed in Volozhin, religious reforms regarding the Jewish could not be actualized. Therefore, they sought pretexts to shut the Yeshiva down.

When Minister Makov was appointed as Interior Minister of the Russian Empire in the year 5639 (1879), reports about the Yeshiva were submitted to his office by informants. They claimed that the Yeshiva had existed for more than eighty years while the authorities knew nothing about its functioning. Therefore, there is room for suspicion that clandestine activities against the government take place there. Based on this, the Yeshiva should be closed, and its directors should be punished. However, Minister Makov related to the Yeshiva with appreciation and stated that since it has existed for approximately eighty years as a high-level house of study, and it was founded by a Gaon and a Tzadik, if is certainly not a place for conspiracies and intent to revolt against the government. Since no iniquity has been found with the Yeshiva for all those years, one must conclude that this house of study serves as a protection against revolutionaries. After an investigation and inquiry, the Yeshiva was certified to function under the supervision of the curatorium of the Vilna district.

However, the government was not content for long. The supervisor of the schools in the district came to the Yeshiva in the year 5647 (1887) along with Yehoshua Steinberg, the superintendent of the school for Jewish teachers, as a special emissary from the district minister. They conducted an exacting investigation. They remained in the Yeshiva for a week. First, they verified the validity of the students' documents, for a rumor had spread that youngsters who were evading army service had gathered in the Yeshiva. All the documents were found to be in order. Then they investigated the procedures of the Yeshiva and its students. There was no matter that they did not thoroughly investigate. They visited the student dormitories to see if they followed sanitation standards. They did not find any fault. When they interrogated the students, each one was asked where they were before they came to Volozhin, and what were they doing there. They especially examined their knowledge of the Russian language. After the investigations and interrogations, they listed

[Page 136]

the Yeshiva students on a sheet of paper to check if their numbers correspond to that which was registered in the Yeshiva ledgers. Everything was in good order.

They cordially took leave of the Netzi'v and left the Yeshiva. However, the Netzi'v was saddened in his heart. He suspected that great changes were liable to come to the Yeshiva in the wake of this visit, which would be enveloped in darkness. Indeed, that which he suspected indeed came.

The Decree of the Minister of Education Delyanov [i]

Translated by Jerrold Landau, based on an earlier translation by M. Porat z”l

Mr. Delyanov, the Education Minister, confirmed for the Yeshiva a curriculum that the Netzi'v could not abide by. There were four sections in this decree, which spelled death for the Yeshiva.

- Introducing secular studies every day from nine in the morning until three in the afternoon.

- The school day should not exceed ten hours within a 24-hour period.

- The learning should be interrupted in the evening and the building should be closed at night.

- The Yeshiva head and all the teachers should be certified with diplomas.

The rule restricting the hours of study was the most difficult, for, as per Rabbi Chaim's spiritual heritage, if the study of Torah were to cease, Heaven forbid, even for one moment, the world would be destroyed. Therefore, this decree was in accordance with “if you cut off its head, will it not die?”[ii]

Some members of the Jewish community supported the government program for the Yeshiva. Erez, the editor of Hameilitz, attempted to explain the benefits that would come to the Yeshiva by introducing secular studies. In his article “The Supernal Yeshiva”[49], he writes the following:

“The main role of the Yeshiva is to instruct the students to swim in the sea of Talmud and halachic decisors, to sharpen their minds with sharp didactics [pilpul]. However, if until this generation, every Jewish man knew how to understand the vast majority of Torah even without knowing anything about world events – times and concepts have changed, and we see how great is the honor of those rabbis who have succeeded in acquiring broad knowledge. Such rabbis have a strong power to attract all factions toward them.”

Erez recommended that the Netzi'v educate his students “To speak and write properly in the vernacular, and to understand it fluently, as well as to master arithmetic, and to learn the annals of the nations of the world, and especially the history of their homeland, the structure of the world in general, and especially of their native land, as well as other such vital knowledge, without which a person may stumble, especially a rabbi amongst our people.”

The Netziv's response to Erez was that this is the way of Torah, that its toil and purpose are fulfilled

[Page 137]

only by those who devote their entire mind to it. It is impossible for a person to become great in Torah when he is occupied with other matters. All Torah giants who are also wise in secular studies are only those who occupied themselves with secular studies prior to immersing their minds in Torah, or after they already became great in Torah. However, when combined, it is impossible to attain the purpose of studies. Indeed, secular knowledge is worthwhile, but Volozhin was only created for Torah study.

The response, published in Hameilitz in 5645 [50], is written as follows:

“Even though his opinion differs from ours regarding how to reach the heights, I am not embarrassed to inform his honor and righteousness that he must learn that we understand the preciousness of the holy Talmud more than he does, and we know that just as pure secularity causes impurity to holy objects through contact[iii], likewise do secular studies, even though they have no trace of impurity or forbiddenness, disrupt the holiness of the Talmud and its successful [study] when they are blended under a single inn.”

Nevertheless, the Netzi'v had no choice, and he was forced to institute the study of the Russian language. The question arose: Who would be the teacher? Certified teachers were required, and there were only three such people in Volozhin: two Jews who had completed their studies at the Seminary for Jewish Teachers in Vilna and served as teachers in Volozhin at the school for Jewish children, and one Christian teacher. The Christian teacher was at a significantly lower level of qualification than the Jewish teachers, but the Netzi'v was specifically worried about the Jewish teachers, lest their influence penetrate to the Yeshiva students. The influence of such people, who were public violators of the Sabbath, was not desired in the Yeshiva. They brought in a certified teacher from Minsk, a G-d fearing Jew. However, for various reasons, he did not teach for very long. He had to choose one of the local teachers, a Jew or a gentile. Rabbi Chaim Soloveitchik opposed a Jewish teacher, and they selected a Christian teacher.

Like all the Christian teachers in small towns who were involved with the children of the farmers, he was quite limited. His education was minimal, and his pedagogic talents quite lacking. He did not succeed in his job, and the students avoided his classes. The Netzi'v, who knew very well the meaning of such avoidance, pleaded

[Page 138]

with tears before the students to continue their studies, for the entire existence of the Yeshiva was dependent on this. However, they did not heed him.

Rabbi Yosef Dov Soloveitchik was among the great opponents of the institution secular education in the Yeshiva. His opinion was that if it is impossible to maintain the Yeshiva as it was supposed to be, it would be best if it were to be closed.

Rabbi Yosi Dov said, “It is not for us to worry about the concerns of the Holy One Blessed Be He and to set up Yeshivas for Him. If we can maintain Yeshivas in accordance with the traditions we have from our ancestors, we are required to maintain them. Otherwise, we have no responsibility. Let the Give of the Torah come and concern Himself with the existence of the Torah.” [51]

Original Footnotes:

- Hameilitz, issue 36, 19 Tevet 5651 (December 9, 1880), and Hameilitz, issue 9, 28 Shvat 5645 (February 1, 1885). Return

- Hameilitz, 28 Shvat 5645. Issue 9, page 139.

Rabbi Kook brings a different version. He writes: “The Gaon the Netzi'v indeed demanded faithful erudition, and desired the honor of Torah, that a rabbi who is the pastor to the flock of G-d should be a man of generous traits, with manners, and worldly knowledge at a level necessary for the conditions of life. He should also know the vernacular language. If he opposed setting times for secular study, it was because he was afraid that the students would make their education primary and their Torah secondary. In any case, he made a great enactment, and asked the students who had already internalized the knowledge of Torah, and have become immersed in it, to set certain times for the secular studies in a special room, and under the tutelage of expert teachers. (The head of the Etz Chaim Yeshiva, Knesset Yisrael, 5648 [1868], page 142). Return

- Rabbi Moshe Meir Yishai: “The Chofetz Chaim” volume I, page 334, published by Netzach, Tel Aviv, 5718 [1958]. Dr. Shlomo Mandelkorn recommended that the “Society of Disseminators of Haskalah” found a secular school alongside the Yeshiva. The following are his words: “Everyone knows that the Yeshiva of Volozhin is virtually the only one certified and confirmed by the government. From way back, it has disseminated Torah and the knowledge of Talmud and halachic decisors, etc., which are 'the life of Judaism and the guardian of Israel amongst the nations.' The only thing missing is secular studies, which are necessary for every person as a human being, and especially or a rabbi, who must be the mouthpiece of the community and fulfil the duties of the deeds imposed upon him by the government. Therefore, would it not be good if the society of “Disseminating Haskalah in Israel” found a school for such studies adjacent to the Yeshiva for the Yeshiva students, who will only spare a small amount of time to easily acquire the necessary knowledge, small in essence and quantity, from expert teachers.

“My heart is certain and sure that my recommendation will be actualized, to rectify a lacuna in the rabbinate, and to fill what is lacking in the community by the good connection between the Yeshiva under the supervision of the rabbi and Gaon, mighty in Torah, and a school under the supervision of the 'Society of Disseminators of Haskalah'.” (“The Have Been Drawn Near,” Literary Treasury, 5648 [1888], pp 41-43.) Return

Translator's Footnotes:

- See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ivan_Delyanov Return

- A Talmudic and halachic principle indicating that the consequence of an action or a situation is certain rather than doubtful. Return

- Based on the complex laws of Tumah and Tahara (ritual purity and impurity). Return

The Yeshiva Closure – “The Destruction of the Third Temple”

Translated by Jerrold Landau, based on an earlier translation by M. Porat z”l

“It was an ordinary winter morning. Little Volozhin woke up from its sleep that day, a chilly day in Shvat, and saw its stormy landscape covered in white. Deep snow covered its hills and slopes, and the wooden roofs of the rickety houses. Even the nearby pine forest was wrapped in a white blanket. The grey skies were low, almost touching the roof of the Yeshiva building that rose proudly over the hilltop, the pride of the scholars. The well-known local swamps were frozen beneath it. Sleighs full of passengers arrived from Molodechna, the railroad station several parasangs from the city, travelling at a high speed. The residents were going to and coming back from the synagogue. Shops were opening. Sleighs of the farmers appeared at the marketplace. Jews seeking a livelihood were scrutinizing the products, incidentally examining the straw, rubbing their hands that were blue from cold, and bargaining over the purchases. They haggled with the gentiles. After a brief time, they went home with a chicken, a sack of grain, etc.

[Page 139]

Rabbis and new Yeshiva students were loitering around Yosi Zelig's inn. Their gaze was still directed only to the legend of the wonderful Yeshiva. There were also householders from all around Russia who had come to see the great tent of Torah.”

This is how Shee'n[52] describes the day of the closure of the Yeshiva. On that day at the beginning of the month of Shvat, 5652 (1892), all the Yeshiva students sat down after breakfast, and occupied themselves with Torah as usual. Suddenly the district governor, the mayor of the city, and policemen entered the Yeshiva. Behind them, a long row of farmers, and villagers remained outside. The emissaries of the government entered. As they entered, one of them told the students to be quiet and stop their studies. When everything grew silent, one official read aloud the edict of the authorities, stating that the Yeshiva was closed. The edict contained three commands: the closure of the Yeshiva, the deportation of the students from the city, and the deportation of the three Yeshiva heads from three districts of the region. The Yeshiva was closed. The building will be sealed. The students were required to come to receive their documents. They were all required to leave Volozhin within three days.

The Netzi'v, who did not understand Russian, asked for the meaning of this. When he heard the translation, he remained seated at his seat as if he fainted. The Yeshiva students removed from the Yeshiva everything that was possible to salvage. The building was evacuated, and the destruction was actualized in full force. The matter became known to all the Jews of Volozhin, and all of them, from young to old, hurried to the Yeshiva building and removed the Torah scrolls. The men banged their hands, and the women wept aloud. The children ran about as orphans, and heard only the words of eulogy, “The destruction of the Third Temple!” Everyone felt that the greatest place of Torah for more than eighty years, was to be destroyed, and there was nobody to save it.[53].

After the officials determined that there was nobody left in the Yeshiva, they locked the doors, and sealed the entrance gate with a large seal imprinted with the insignia of the government. It stated that anyone who breaks the seal was liable to a severe punishment. With this, the closing ceremony ended. The grief was very great and deep. The large congregation that gathered around the Yeshiva did not have the spirit to leave the place. The Netzi'v sat on his chair, with his tears choking his throat, and words were caught in his mouth.

The closure of the Yeshiva made a frightful impression not only upon those who were immersed in Torah, the Rabbis and scholars of Judaism, but also upon every Jew. Everyone understood that the destruction of the Yeshiva of Volozhin was a national disaster – a loss for all of Jewry, for anyone who had studied in the Yeshiva, even for a brief time, became a lifetime partner in the weaving of the golden chain of Judaism.

Original Footnotes:

- “When the Gates Were Locked,” Hatzofeh, 8 Shvat, 5702 [1942]. Return

- The idea that the Yeshiva disbanded from the inside, in accordance with “Thy destroyers and they that made thee waste shall go forth from thee” [Trans: Translation from Mechon Mamre, Isaiah, 49:17. https://mechon-mamre.org/p/pt/pt1049.htm ], was proposed by the writer Meir Rivkin in his article in Hamashkim, “The Volozhin Yeshiva During its Final Years” Woschod, 1895.Return

[Page 140]

The Netzi'v Conducts Tikkun Chatzot Next to the Yeshiva Building[i]

Translated by Jerrold Landau, based on an earlier translation by M. Porat z”l

The Yeshiva students, depressed and humiliated, left town to return home in groups. Peasant with horse-harnessed carts gathered from the entire region to transport the Yeshiva students to the railroad station. Bitter cold reigned outdoors. A blizzard started, covering the face of the entire world. The lads sat in the wagons, doubled over, crowded between their clothes and their baggage. They were overcome with grief and eaten by agony. The wagons seemed like a row of corpses that winter night, along the route from Volozhin to Molodechna.

Toward evening, the Mincha service was conducted for the first time in a different place. The Netzi'v stood in his corner, praying in his usual manner, pronouncing each word aloud, as if he were threading pearls. In the middle of Ashrei, he could no longer restrain his emotions. He groaned deeply and peered through the window at the dark Yeshiva building, which appeared before his eyes as a corpse in front of the entire Jewish people. Suddenly, he raised his arms heavenward, regained his composure and justified the judgment. In the sad melody of the Yeshiva, he recited the verse: “G-d is just in all His ways, and gracious in all His deeds.”[ii]

However, the Netzi'v was not calmed. He mourned over the Yeshiva. It was a winter day, and a heavy snowfall fell over Volozhin. The windows of the Yeshiva, which were illuminated all night for ninety years, were sealed shut and spread a pall. The local Jews were wary of approaching the building – out of sublime fear of the “deceased” – the death of the community of Israel. Only the Netzi'v remained in Volozhin. He was granted the permission to remain for several weeks. A few days after the closure, footsteps were noticed in the snow upon the Yeshiva path. People recognized the footsteps of the lonely Yeshiva head. Late at night, when the marketplace was deserted, he would leave his home, stand next to the lock door, and recite the Tikkun Chatzot service. There were snowstorms, cold that froze the blood, and the government ban, but he, the wonderful guardian, to whom the soul of the building had become his own soul, stood there. A heavenly voice emanated from his throat into the space of Volozhin: “Alas for my children who have been exiled from the center of their lives, and are wandering along seven paths.” He was unable to part from his nest, which he protected under the shade of his wings for forty years. His footsteps were also found along the path leading to the gravesite of the rabbinical family [Beit Harav], where he used to go to supplicate at the grave of his grandfather, Rabbi Chaim of Volozhin, at any time of tribulation. He would prostrate himself and put forth his supplication and embrace the cold monument in which the holy body was interred.

Translator's Footnotes:

- A midnight set of dirges recited in memory of the destruction of the temple. Generally, Tikkun Chatzot is recited by especially pious people, and is not part of the obligatory prayer rites. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tikkun_Chatzot https://halachipedia.com/index.php?title=Tikkun_Chatzot Return

- This verse (Psalms 145:17) is part of the Ashrei prayer, recited three times daily, including as the opening of the Mincha service. The justification of the judgment (Tzidduk Hadin) is a blessing recited upon receiving very bad news, especially upon hearing the death of a close relative. Return

The Sunset of the Netzi'v Begins

Translated by Jerrold Landau, based on an earlier translation by M. Porat z”l

After the closure of the Yeshiva, the Netzi'v left for Pinsk, and then to Warsaw. On the last day of Passover, the Netzi'v ascended the bima to bid farewell to the people of his community. The departure from Volozhin, where he was raised and educated, and from where his fame spread throughout the world, was very difficult for him. Tears flowed from his eyes, and his voice could be heard with difficulty. Seeing the elderly Gaon weeping aroused great agony. He left the city the day after Passover. Many of the Volozhin residents accompanied him. Volozhin was left enveloped in grief, as its glory and splendor was taken away from it.

[Page 141]

In his memoirs, the preacher Tzvi Hirsch Maslianski described the Netzi'v during his declining months[54]:

“During that time, there was a convention of the local Chovevei Tzion in Warsaw. I too was present at that gathering. Suddenly, as I scanned the people gathered with my eyes, I saw before me the Gaon, the Netzi'v of Volozhin, sitting at the head of those summoned. How surprised was I to see the great change that had taken place in the look of his face and the build of his body, since four years previously,when I had seen him before me alive and fresh, alert, and full of spiritual energy. He, the elder, encouraged me, the youth. He spoke to my heart and strengthened my hands, encouraging me to continue to speak and encourage the revival of Israel in its land. Now, he sat before me depressed and bent over. His face was gaunt and pale, and he exuded weariness and exhaustion. I knew the reason for the change in this exalted man. During the four years, a terrible event had taken place, which destroyed the world of this Gaon, and forcefully severed the wick of his soul – the closure of the great Yeshiva of Volozhin, and the severing of the golden chain that had extended back from the days of Rabbi Chaim. His great, wide heart could not withstand the terrible destruction, and had been cut to pieces.

“After the gathering, I approached the Netzi'v to greet him. We stood and chatted for a period of time. When I parted from him, he hugged and kissed me, and spoke the following words to me in the presence of all those gathered: 'I know that I will no longer merit to make aliya to our Holy Land. May the G-d of Zion be with you , and when you come to the Land, bring my bones with you from here.'”

The Netzi'v intended to make aliya to the Land, but he was forced to defer it due to the debts that were upon him. In his letter of Monday, 21 Adar 5652 [1892], the Netzi'v complained to his student, Rabbi Eliyahu Aharon Milikowski, about the debts that he had incurred on account of the Yeshiva:

“In truth, my close friend said to me that if I had not had debts, I would have set out immediately after the festival to our Holy Land to rest there after bearing the burden of the Yeshiva for 38 years, and to die there [and be buried] at the grave of my father, may the memory of the righteous be blessed, in Jerusalem, may it be built up speedily in our days. However, the debts that I owe force me to leave my wife and children, may the live, and to remain in the Diaspora, to collect, through our great sins, and to disburse. All this affects my soul, and my head spins.”

The decline of the Netzi'v began. Eliezer the son of Zeev Perski writes[55]:

“Volozhin, 14 Tammuz. Today, a telegram reached the honorable Rabbi Chaim Hillel.

[Page 142]

from the Rebbetzin, Mrs. Batya Mirl, the wife of the rabbi and Gaon, our rabbi Naftali Tzvi Yehuda Berlin. It stated that her husband is sick, and he requested that Psalms be recited for him. In the wake of this sad telegram, immediately all the residents of our city gathered in the Great Beis Midrash and recited Psalms with deep devotion, pouring out their words before the Healer Of All Flesh, that He should send a complete healing for his serous illness. Rivers of tears were shed. After the recitation of Psalms, Rabbi Ben Tzion Shu'b [the shochet], a great friend of the Rabbi and Gaon the Netzi'v, may he live long, ascended the bima, and recited the Mi Sheberach prayer for the benefit of the sick person. The entire congregation pledged on his behalf eighteen zloty to Bikkur Cholim, and eighteen zloty to the Talmud Torah. In this merit, may the Healer Of All Flesh grant him a complete recovery, strengthen him, grant him life, and extend his days and years in good spirit and pleasantness, as is the will of all residents of our city, his faithful admirers.”

Original Footnotes:

- Haivri, issue 32, 6 Elul 5677 (July 24, 1917) [Trans: I believe something is incorrect on one of the dates, probably the English date, as the date is too early for 6 Elul, even according to the Julian calendar.] Return

- Hameilitz, Thursday, 22 Tammuz 5653 [1893]. Return

The Death of the Netzi'v

Translated by Jerrold Landau, based on an earlier translation by M. Porat z”l

In Hameilitz of Friday, 29 Av, 5653 [1893], Fogel announced the following frightening news: “Warsaw, 28 Av (July 29, 1893), at 7:00 a.m. The rabbi, the great luminary, the former head of the Volozhin Yeshiva, our teacher Naftali Tzvi Yehuda Berlin, passed away today.”

Ben-Tzion, the shochet of Volozhin, writes the following about the heavy mourning of the Jews of the city[56]:

“Alas over the news that has arrived, the terrible, vexing news that was brought to us today from Warsaw over the telegraph lines, that the crown of our heads, the splendor of Israel, the portent and glory of the generation, the great Gaon, the famous Tzadik, Rabbi Naftali Tzvi Yehuda, the son of Rabbi Yaakov Berlin, may the memory of the righteous be blessed for life in the world to come, has fallen. The head of the rabbinical court and the head of the Yeshiva of Volozhin has been taken from us today. This awful, saddening news, which brought sorrow to the House of Israel in general, and to the community of Volozhin in particular, the city in which he served for close to forty years, reached us toward evening. The entire city was flabbergasted, and everyone, from young to old, gathered in the Great Beis Midrash to eulogize him appropriately, and to weep for him. The weeping reached great heights, and the flood of tears grew like a flowing river breaking through the courtyard of the House of G-d. Mourning and sadness was great in Volozhin.”

“The angels were victorious on the heights, and the Holy Ark has been captured. The Netzi'v was gathered unto his people.” The Netzi'v was gathered to his people on the 29th of the month of Av, 5653, in the year of “my eye is poured out”[i]. The newspapers announced that his son, Rabbi Chaim Berlin, included in his eulogy for his father the words that our sages stated in Yalkut Yeshayahu, 21:

“Our rabbis taught that when the First Temple was destroyed, what did the youths of the Kohanim of that generation do? They gathered in groups, with the keys to the Temple courtyard in their hands, ascended the roof

[Page 143]

of the sanctuary, and said before the Holy One Blessed Be He: 'Master of the World! Since we did not merit to be the treasurers, here are your keys given back to you. They threw them upward. Immediately, a form of a hand came forth and accepted them.'”

Original Footnote:

- Tuesday, 10 Elul, 5653 [1993] Return

Translator's Footnote:

- A literary technique exists in which a Hebrew year is represented by a relevant Biblical verse, some of the words of which form an acronym of the year. The

verse fragment here is from Lamentations 3:49 [עיני נגרת] – with the second word matching the year, albeit the original ה was interchanged with a ת. Return

The Moving Eulogies for the Netzi'v

Translated by Jerrold Landau

On the day of the funeral of the Netzi'v, Y. Ch. Zagorodski sent words of eulogy about the Netzi'v to Hameilitz, expressing the greatness and lofty value of the illustrious deceased. At the end of his words, he tells[57]:

“The terrible news of the death of the Gaon the Netzi'v flew through all corners of Warsaw like an arrow from a bow. From the morning, masses and masses came to the house of the deceased. People from all segments of the nation came to stand around the body of the deceased, and to ponder his greatness and the magnitude of the loss to our nation with the death of this great giant. The deceased was lying on straw on the ground, as per Jewish law. There was a black shroud atop him, and atop the shroud, many books and tractates, a large heap of books. Around this holy heap were tens of candles. Children and youths from the Talmud Torah were standing from the morning, with the Psalms of David the son of Jesse upon their lips. 'For You shall not abandon my soul to the netherworld, nor will You let your righteous one see the pit'[i]. Indeed, people such as the Netzi'v do not die and do not descend to the netherworld, for their memory lives – lives forever in the hearts of the myriads who honor and revere them. Generations will pass, hundreds of years will go by, and the memory of the great Gaon will stand as it is.