[Page 84]

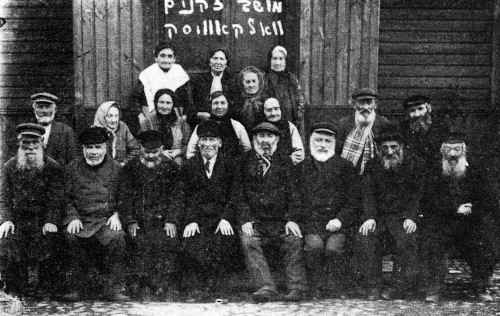

The Volkovysk Old Age Home

|

|

The Volkovysk Old Age Home

Right to Left, First Row Seated: Ahareh the Shammes, L. Ein, Meir Shiff, Esther Weinstein (die Podriachikheh), Abraham Nissan Kronberg, Tuvia the Smith (from Zamoscheh)

Second Row, Standing: Herschel the Wagon Driver, Two unidentified Wagon Drivers, Gutka (Mendel the Dayan's daughter), Unknown, Wife of Yankel the Smith (from Zamoscheh), Mikhlah, the Blind Man's wife, Chaya from the Laundry, Unknown, Aydeleh Mazover, Chasia Pozniak, Nionia, the wife of the Wagon Driver, Tzipa, wife of the Shammes, Dina Leah Jesierski (the Dye-Maker), Unknown

Last Row: Shimon Ada's, the Melamed, Eli Dina's (the Melamed), Unknown, Unknown, Tzal'keh the Wagon Driver, Yankel the Smith, The Blind Pauper, Moshe Goshchinsky (The Blonde), Alta's brother, from under the Barg, Shimon the Chimney Sweep, Unknown |

|

|

The Old Folks at the Old Age Home, Prior to the Second World War |

Volkovysk, like many other important Jewish communities in Eastern Europe had its own, well-organized Old Age Home, in which old Jewish men and women without family were supported in dignity, in which all of their material and spiritual needs were attended to.

The residents of the Volkovysk old age home came from all classes and walks of life: former storekeepers, workers (hat-makers, tailors, bakers, chimney sweeps, etc.), and near-clergy (shamashim, teachers). Here were found people who were born in Volkovysk, and grew up as the city itself developed, spent their entire lives there, transacted and worked there, brought children and grandchildren into the world, raised and married off sons and daughters, and remained alone in their twilight years: children went away into the greater world, their own energies waned, and it became difficult to make a living. There were among them, people who were not entirely

[Page 85]

impoverished, or they received a fixed stipend from their children in America, but they were very lonesome, they were either widows or widowers, they did not have the capacity to prepare their own meals, or take care of themselves, especially on days when they either felt weak or unwell, as happens so often during old age.

For this class of people, the Old Age Home was both a residence and a club at the same time. They had their friends there, people of their own age, with whom they could converse about the “good old days.” They had comfortable quarters there, where tasty and nutritious meals were prepared for them, where their laundry was washed; they also had their own synagogue there, a place for prayer and study. In the Old Age Home, they could live out their years in dignity and tranquility – in their own city, which was so deeply imbedded in their hearts, where that had lived through so much joy, and suffering, and where the graves of their parents and grandparents were located, and those of their near and dear relatives and friends.

The Volkovysk Old Age Home developed a good reputation for itself, and during its final years it attracted many of the elderly from surrounding towns, who [also] came there.

For this high level of regard achieved by the Volkovysk Old Age Home, thanks are due to its loyal activists: the three presidents – Meir Shiff and (after his death) Mr. Yaakov Winetsky, the pocketbook maker from the Wide Boulevard – Manya Galai, Leib Heller (Weiss), Yaakov Weinstein, L. Ein, Mrs. Esther Weinstein, A. Offenberg (Secretary), and others. These active members spared no effort and energy in placing the Volkovysk Old Age Home on a healthy foundation, so that it will engender respect for the Volkovysk Jewish community.

* * *

The Volkovysk Old Age Home was founded in 1908 (5668) at the initiative of Reb Schraga Feivel Heller. In 1927 there were 18 aged men and 17 aged women who were being cared for along with the others: three meals a day were prepared for them daily, and tea with sugar was given to them on request, at any time. Expenses, except for wood, was covered by America – was about 800 zlotys a month. Income came from the following sources: 1) monthly fees from the residents – 150 zlotys a month; 2) from the city administration – 80 zlotys a month; 3) from various contributions. This, however, could not cover all the expenses of the Old Age Home, and a large portion of the income came from Volkovysk landsleit in America.

Under the direction of the very energetic president, Meir Shiff, the facilities and appearance of the Old Age Home were greatly improved. A substantial renovation of the building and its rooms was carried out, which gave them an entirely different appearance. This attracted financial resources from a variety of sources. Many solitary old people from families who previously had means, came with requests to the Old Age Home administration that they be taken into the institution. But this revealed that there were no free places available for these new candidates for the Old Age Home. Mr. Shiff then decided to put up another building, in order to be able to accommodate everyone who had a need for such an institution. Through his good relationship with the authorities, it became possible for him to acquire a supply of wood from the municipal forests that was needed for the construction of the building. Contributions for the new building also came from other sources, and the building was erected in a matter of several months.

We find an interesting portrait of the Volkovysk Old Age Home, under the direction of Meir Shiff in an article by Alexander Kalir that was published in the Volkovysker Leben of 1930. The writer describes how he went for a visit to the new building of the Old Age Home with the director, Mottel Leib Kaplan, over which appear the words: “An Old Age Home – Cast Us Not Into Old Age:”

[Page 86]

“A clean, neat yard with the old building of the Old Age Home on one side, and on the second side – a spanking new just-completed wooden building, with an attractive porch, a regal facade, which brings to mind an inn or a pension in Otvotsk or Schvieder.

We go inside. Through a corridor, we come into a wide, open and well lit eating room: three large, long tables are arranged in a “U.” An eight-branched candelabra hangs over them – on the wall is a large circular clock. A large coal stove spreads an inviting warmth [throughout the room]. A spigot juts out of the stove that dispenses tea all day long. At a side – in a wall, is a square little window, through which food is served from the kitchen.

We went into the kitchen: A big cooking surface, and surrounding it are tables covered with metal pots. Solitary ladies stand about, and are rolling out rolls of noodles. It is a midday week, and we wondered: “Are you making noodles already for the Sabbath?” – we asked them – “No” – they answered us – “We are preparing the evening meal – dairy noodles.” “Are these the cooks?” I simply tossed the question at her, not having anything else to ask. “No, no – the two elderly Jewish ladies quickly answer to “assure” us, – the cook is a [much] young[er] person!”… We smiled at the answer, and went into the “pantry:” There is a variety of foodstuffs, sacks of flour, a crock of cucumbers, and other things to eat. In general one sensed the skilled hand of a capable homeowner, with a strict economical discipline wherever we turned. From there we come out into a large fenced yard. Several sheep were grazing on the lawn, chickens and roosters walked about.

– These have already been provided for kapores[1] – the President, Mr. Shiff explained, pointing to the birds, and then led us to the brook.

–What is there? – A beach perhaps, also?…-- director Kaplan says jokingly – but instead of a beach, we see a setup for handling the laundry for the old folks, and a place for summer wood.

Turning back, Mr. Shiff points out the bell, which joins the two buildings, and pulls on the handle … the oldest residents begin to come out, appearing in the yard. They have the ‘privilege’ of eating their midday meal earlier. May they eat in good health.

In the old building we meet with old people from many places. Every visit bears witness to the type of life the individual lived, and what sort of 70 years have transpired for him.

Here, we meet an old man who greets us with a broad ‘bonjour’ and immediately as he sees us begins to recite declensions: Imenitelny – kto chto, roditelny – kovo chevo, datelny – komu, chemu…[2] – and if you are interested, he will recite by heart the poem Чиж и Соловей Приходский Училище[3] … many years before, he studied in a [4] he recalls (kein ayin horeh).

[Page 87]

– Who is this man? – director Kaplan asks.

– Reb Shimon the oven cleaner – President Shiff answers.

– The chimney sweep – Reb Shimon corrects.

We take our leave of him with a friendly ‘au revoir’ wishing him long years…

We peek into the rooms. Here, an elderly couple is conversing so friendly and lovingly, but they are sitting – back to back with each other.

In a second room – two elderly Jewish women. One is lying down on the bed asleep, a second is sitting on her hand deeply concerned, bitterly worried.

What is this poor lonely old woman thinking about? – the question enters my mind – about her long gone youth? About her children who are spread all over creation? About her lot… I get choked up just looking at her, and it is at this point that I am reminded of the [High Holy Day Prayer] “Cast Us Not Into Old Age,” and it is here that the line becomes completely clear to me…

But Mr. Shiff doesn't permit us to think, he takes us into the office… In the office, Abraham Offenberg the secretary, receives us in a friendly manner, who informs us about the features with which the new building has been equipped: the foundation was donated by the recently deceased Reb Sholom Barash; 500 dollars – Horaczy Heller (the House is named for him); the Grafina[5] Bronitska – nine square meters of lumber; the well-known alderman Shirayev – an overcoat The Rozher Cement Factory – 15 ‘rounds’ of cement, A Warsaw Company, Degenschein – a case of glass; Mrs. Fradl Shiff – the Candelabra; A Warsaw Company, Applebaum – the clock…

Everything was acquired through the efforts of President Shiff – our friend Offenberg explains – he traveled everywhere personally, and at his own expense.

We leave the office. In the Bet HaMedrash Room, the old men are already seated around a table and are studying a chapter of the Mishna[6]. The ritual slaughterer Reb Reuven Kagan is leading the lesson…

We thank president Shiff, and leave the institution.

* * *

For his dedicated work on behalf of the good of the institution, it was decided after the death of President Meir Shiff to place his portrait in the new building, which was constructed as a result of his efforts.

[Page 88]

After the death of Mr. Meir Shiff (in the year 1936) it was decided to appoint the retiring, shy pocketbook maker Yaakov Winetsky as president of the Old Age Home, whose wife was the cousin of the well-known Volkovysk activist and merchant Moshe Zelitsky. The pocketbook maker was a noteworthy person, a common man of heart, who with his effective activity on behalf of anonymous charitable giving (the institution that had the purpose to secretly assist those who had fallen from positions of means, and for a variety of reasons became impoverished, but were to ashamed to ask for help) endeared himself to all classes of the Volkovysk Jewish population.

After the Russians entered the city, the Old Age Home functioned in a normal fashion. However, at the time of the German bombardment the Old Age Home was entirely burned down. The old folks were dispersed into various homes, to their relatives or simply to people who knew them.

Under the German occupation, a portion of them died from the difficulty of living circumstances. When the forced expulsion to the bunkers took place, only the strongest among them were able to go away with their families. The weaker ones, who could not come along, were gathered on November 2, 1942 in the Talmud Torah, and shot by the Germans. The remainder of them, who survived the period in the bunkers, before the forced expulsion from the bunkers, were brought together in the notorious Bunker Number 3 where they were gassed.

Translator's footnotes:

- The purification ritual before the Yom Kippur fast, where the sins of an individual are ‘transferred’ to a rooster, which is then ritually slaughtered and cooked. A variant of the ritual of the scapegoat. In the absence of fowl, coins are often substituted. Return

- The speaker is showing off his knowledge of Russian. These are respectively the nominative, genitive and dative case endings for Russian nouns. Return

- The Finch and the Nightingale Return

- A Parish School Return

- Wife of a Graf – a nobleman Return

- The first part of the codified Oral Law, preceding the Gemara, but together with it, forming the Talmud. Return

This material is made available by JewishGen, Inc.

and the Yizkor Book Project for the purpose of

fulfilling our

mission of disseminating information about the Holocaust and

destroyed Jewish communities.

This material may not be copied,

sold or bartered without JewishGen, Inc.'s permission. Rights may be

reserved by the copyright holder.

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Vawkavysk, Belarus

Vawkavysk, Belarus

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Yizkor Book Director, Lance Ackerfeld

This web page created by Jason Hallgarten

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 16 Oct 2022 by LA