|

is the Russian border.[3] Scale: 1:600,000 - each cm. on the map represents 6 km. in distance

|

|

[Page 7]

Translated by Mira Eckhaus

About ten years have passed since the time that I proposed to publish the Olkeniki [memorial] book until today, when we had the privilege of publishing it.

Difficulties and doubts, problems and misgivings accompanied those involved in the matter through this long period. And when we have come this far, and we present the book to the people of our town and the general public, it should be noted in advance that we do not pretend to give a scientific historical assessment of our small town, and we do not submit to the public refined literary material. The material, for most of its part, was written out of longing and from the aching hearts of the generation of ancestors, who witnessed the Holocaust and wanted to establish a monument for their town, and to instill in the children and the next generations memories and experiences from the landscape of their homeland, from their parents and from the holy community that was destroyed and lost to them and to the people of Israel forever.

The chapters on the Holocaust were written by the survivors or written from their words, as they recreated the fateful moments in their lives, when they stood on the brink of death.

It is possible that due to the tumultuous times, and due to the distance of time and place, that there are inaccuracies or repetitions and we ask ahead for the reader's forgiveness.

We know, and we emphasize this with regret, that we did not cover all of the life of the town in the last generations and that we were not given the opportunity to give important episodes in the life of the vibrant youth in the last years before the Holocaust. Likewise, precious, important, and holy figures were not mentioned in the book, because none of their family members were left [alive] to put their memories onto paper.

And now I find it a pleasant duty to thank the “Association of Former Residents of Olkeniki [Lithuanian: Valkininkai] and Its Surroundings” and the few residents of our city who live overseas, who assisted wholeheartedly and with great faith to the success of the enterprise.

My thanks go to the writer Chaim Grade[1] from the United States, who lived in our town during his studies in the yeshiva and immortalized it in poetry and prose, for agreeing to publish excerpts of his work in this book.

We are also grateful to the writer G. Einbinder from the United States for making available to us some of the material he recorded from the survivors of Dakashnia.[2]

May all those who participated in the writing and sent me the pictures of their loved ones be blessed. And last, but not least, our gratitude goes to Mr. R. Hasman, and the “He'Asor” [the decade] printing house whose efforts have given the book a nice shape.

Haifa, 15th of Sivan 5720

10.6.1960

|

|

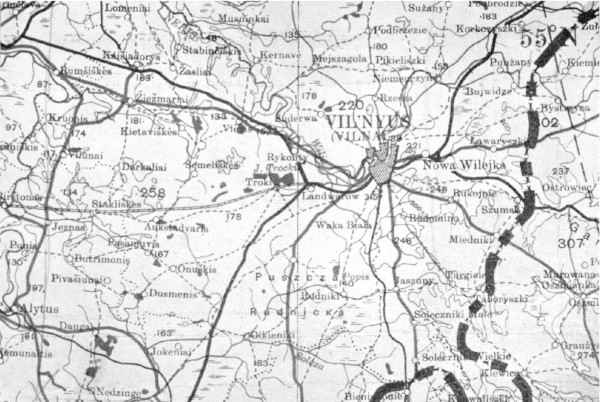

| Olkeniki on the map of the southeast of “independent” [inter-war] Lithuania. The line on the right is the Russian border.[3] Scale: 1:600,000 - each cm. on the map represents 6 km. in distance |

Translator's footnotes:

by S. P-R

Translated by Mira Eckhaus

Our small town was not among the large communities that were destroyed and were privileged to have built for them memorial monuments in the eternal life of the nation. But the disaster, the sorrow, and the agony have no quantitative dimensions, and the mourning of the individual, the mourning of the remnants of our town, can be greater than Job's mourning.

Each of us carries within us a black stain of mourning which will not be erased all the days of our lives, like the black stain of the “memory of destruction,” which stood out on the western wall of the synagogue in our dear town, which was burned and no longer exists.

Songs and legends were created about the death trains that transported European Jewry to destruction. Who can describe the situation, the thoughts of terror, of the people of our city, when they were being transported in farmers' carts on the road going up to Eishyshok, through the wonderful pine forest, when the wind whispered among the branches of the trees the secret of death in the ears of those going on their final journey. Where is the poet who will sing the song of doom about a whole, holy, and pure community that was being led to the slaughter, in the wonderful fall of the year 5702 [1941], on the eve of Rosh Hashanah?

Our town did not have the privilege that its saints will reside in it, but their terrible fate, which cannot be understood and measured, was to be dragged about 21 kilometers to the neighbor city, Eishyshok, which was related to Olkeniki in family ties, trade ties, and cultural ties.

The remnants of the Eishyshok people who live in Israel saw us as partners in disaster and fate, and they found it appropriate to share with some of our townspeople in their grief, and we thank them for that, but in the depths of our hearts there was a doubt, if our community of Olkeniki is not worthy, that we, the remnants, will find the way and the time to establish a monument for our families and our town.

Each of us has something in him from the landscape of our dear town, just as he has virtues and talents from the heritage of his dear parents. After all, over forty years have passed since I left the town, and I remember every protruding stone in the street, every turn of the Marchenka[1] River, every leaning tree on the road, because there I absorbed the first strong impressions of my childhood.

This is the physical, observable Olkeniki - its rivers, its forests, its watery lakes, and its silent fields. But there is a spiritual and cultural Olkeniki. This was the town of Olkeniki which had raised generations of hardworking people, people of culture and creativity, and had created a special way of life that characterized it. This ancient community, which knew how to live in holiness and purity, in which even the common people within it studied the Torah every day and worked and learned the ways of the world, who purified the nation's theory of life and the tradition of the ancestors, were engaged in the Talmud and Midrash, [as well as] world affairs and literature. The spiritual Olkeniki stands out among hundreds of other towns in Poland and Lithuania. And in this we will place a written memorial to it, from the scriptures of its remnants in the land of Israel and overseas.

Tel Aviv, 1953

Translator's footnote:

by S. P.

Translated by Mira Eckhaus

When I think about the personalities and characters of the town, in recent and past generations, about their way of life on weekdays, on the Sabbaths and holidays, on tranquil days, on emergency days, and during the Holocaust, I clearly see the abundance of spiritual treasures, the mental forces, that the Jewish town had accumulated and that have not been expressed. The few members of the town that left it and went out into the wider world, glorified its name publicly, and dozens of its townspeople from the last generation, who left it and emigrated to the land of Israel, found a relief for the spiritual forces that were stored within them and used those forces in the work of building and creating.

Among the members of our tiny town, who were and are active in many areas of our lives in Israel, we will recall here the late Prof. Yosef Kloizner, who was raised and born in a small house in our town, and was first educated by the melamed Reb Tzotsa, who lived on a hill near the Beit Midrash. It should also be noted that [Israel's oldest civil engineering and construction company] “Solel Boneh” began with people from Olkeniki, headed by the energetic Hillel Dan. In the cities, settlements, and kibbutzim in Israel, many of our townspeople are active in the areas of education, economy, and industry.

It has not yet been investigated how and when the process of recovery and regeneration in the town and the country began. How did it happen that the sons of petty merchants and hard-working shopkeepers, the sons of oppressed workers and artisans, left the town, rebelled against their parents and the quiet life of the town, and went out into the world. Who inspired in them the desire to join associations, to replace their spoken language [Yiddish] with the Hebrew language, to start working in jobs that were simple and, in the eyes of their parents, despicable, and finally to leave their homeland and emigrate to Israel.

Where lies the pushing and driving force for all of these, and what are the roots from which the people of the Third Aliyah[1] and those who followed them were propelled? Apparently, the spiritual seeds were hidden and concealed for generations in the town's treasure and were passed down from generation to generation, from fathers to sons and, with no relief for these forces, the townspeople invested themselves in simplistic spiritual activity, in wars over beliefs and opinions, in the war of languages, etc. Olkeniki was blessed in this, that all the upheavals in the Jewish community in recent generations found faithful echoes in its community life.

From the meeting of the State Council of Lithuania in our town, to the war of opponents against Chassidism, education and assimilation, Zionism and its opponents, the revival of the Hebrew language and advocates of Yiddish - all of these left their mark on the small town, which never had more than 150 families and never more than 1,000 people, even in its prosperous times.

May its memory be preserved in the hearts of future generations, as a faithful monument to the creative power of our people in exile and in their country [Israel].

Footnote:

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Valkininkai, Lithuania

Valkininkai, Lithuania

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 18 Jan 2023 by MGH