|

|

|

[Page 254]

Translated by Meir Bulman

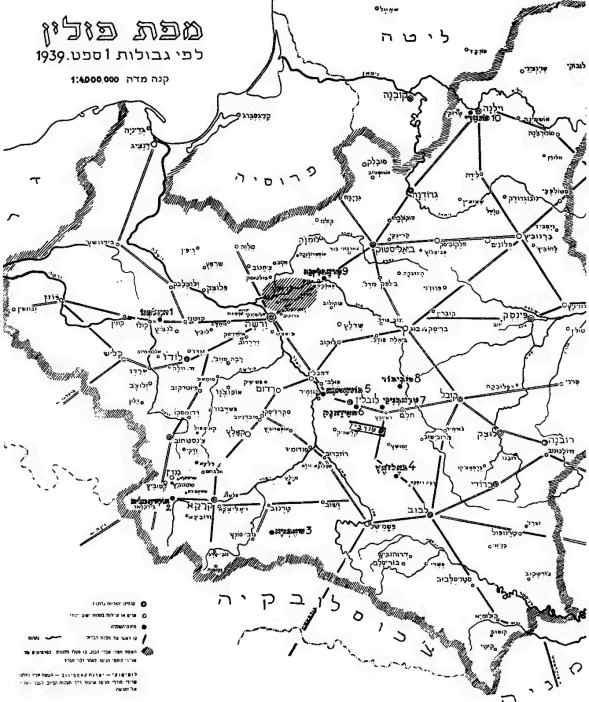

This map are marks 10 main extermination sites which the Germans erected in Poland starting with the occupation 1940–41. Many labor and concentration camps are not mentioned here, including large ones like Janówska in Lwow, Kraków–Płaszów, and others, which were also camps for systematic extermination, and in all the Germans massacred local Jews.

|

Shlomo Zissmilkh

(man of the underground)

Translated by Meir Bulman

After the occupation of Poland and the Russian–German agreement, the Russians retreated from the occupied Polish territory from the western side of the Bug river, with the fixed border along the river. That was in October 1939. In that month, on the holiday of Simchat Torah, the Russians left Turobin. They were immediately followed by Nazi forces, and as soon as they arrived they conducted a weapons search. There was not a home where they did not present themselves.

I remember an interesting event from that day: in our home we housed five refugees from Krakow. The German soldiers entered our homes and instructed, “stand still with your hands up.” (Upstehen Händen in den noch) The refugees, who spoke German, froze in place and remained in their beds without grasping what they were told. Only after the soldiers began hitting them with their rifle butts they recovered and understood the situation.

At the start of 1940 the population had to sustain itself economically. There were weak business ties. A few merchants brought products from nearby villages to export to Lublin in wagons (buses were not operating.) They purchased products that were unavailable in town and brought them back. The Germans treated that trade like smuggling, and due to the ban one could not move merchandise to and from Lublin in the daytime. There was also a night time curfew. The import and export from Lublin were done at night anyway. In one trip to Lublin, I joined six passengers, one of whom I remember, Chan'che wife of Avraham Liberbom the hatter. Before we reached Wysokie, the Germans captured us and imprisoned us in the Wysokie jail. We did not sleep that night because we feared our end. There were precedence for that fear as the Germans simply shot captured smugglers. As morning approached an officer entered and asked where we were traveling to at night, and we replied honestly and told him we were traveling to Lublin to purchase necessities. Based on that he freed us and we

[Page 257]

continued our journey to Lublin. In Lublin we bought food items, sewing instruments, leather, etc. The stores in Lublin were already half shuttered, but one could still obtain merchandizes. Under those condition Jews traveled to Lublin two–three times weekly to shop and on their way, there brought produce from villages. The situation continued the entire winter of 1940.

The German army was stationed at the outskirts of Turobin. According to their plan they worked the Jews in clearing snow, ditch digging, trash removal, and other services for the military. In place of a salary the Germans gave beatings, and more than once caused grave injury. One day, I walked through street in Lublin and heard “snatchers” and until I managed to escape to Kowalski Gate number 3 I was captured by an SS man who brought me to Shvinta–Doska [?] where there were many detainees and we were all led to a farm near Maydan. We were worked clearing the territory of mud and clearing trash from the stables. The bearded Jews among us were shaved [?] using lit candles. Suddenly, they gave an order to run and began shooting, to injure or kill. I worked diligently and tried to avoid any reason for assault. The whole day an SS guard with a lash passed by and hit the workers. Toward evening the SS passed by me and I asked if I can go home. He replied, “yes, you worked diligently. Go home.” As I was walking away I walked back and saw the same SS talking to a Jew, who possibly also asked to go home. In response he took out his gun and shot him on the spot. After I saw that I left quickly and traveled home to Turobin. Such a day was called, “snatching day.”

In the summer of 1940 there was a forced labor quota which had to be fulfilled by the Judenrat. In one convoy, 150 Jews were sent to work in Zamość, and I was in that group too. The job was to building walls using pedestals and wood by the river bank. The workers slept in barracks and received a little food through representatives of the community. Each community supplied food to its members. At the same time the representatives of Zamość brought food they extracted me from the work camp thanks to family members I had in Zamość. My younger brother remained in that Zamość camp that whole summer. In addition to the worker quotas there were also snatching days in Turobin.

At the start of 1941, anti–tank ditches were being dug along the Bug River. Many people were snatched for that job. In Turobin 16 people were snatched. The snatched Jews from Turobin were sent to the Rava–Rus'ka area. The arrangement was that each community was permitted to bring food and clothes for its people once every two weeks.

In one day in May 1941, in early evening, as the community people walked through town to gather clothes and food for the forced laborer, a car with 4 Gestapo men. One of them One of them guarded Velvel Birnbaum's home so that the people in it would not leave, and the other entered. We immediately heard an explosion and understood a hand grenade was thrown. Mottel Yakovzon heard the explosion and struck the SS man to the ground and escaped outward, and I followed him and escaped too. Yakov Feder survived because he fell to the ground and the murdered laid on top of him. That day, those SS men passed door to door and killed every Jew they came across. 130 people died that day. That was the first big day of slaughter. People began to grow accustomed to those horrors. The fear continued and occasionally some were killed and others were snatched and shipped. It continued until the winter of 1942.

[Page 258]

In the winter of 1942, the Jews continued to work for the Germans. The synagogue was converted into a warehouse for the German army. At That same time, some compulsory laborers returned from Zamość. They told of a short SS supervisor who rode a white horse and every day had to find some victims and shoot them.

Most expulsions were done in the summer of 1942. I was in the group last expelled, dubbed “Judenrein” during the holiday months in October 1942. On Saturday morning, an order was issued that no Jew may remain in town by 7 in the evening. The Germans brought several wagons, and the expulsion began.

I remember that among those expelled the second time was my mother OBM, and they were brought to the Trawniki train station. All those expelled were placed in freight carts. After the train n began to move in the evening, my mother jumped through the slit in the car. She sprained her foot and made her way home leaning on a stick, dozens of kilometers.

The final expulsion was towards Izbica. The procession, numbering inn the thousands (there were some refugees from Lodz among us) made its way slowly to Izbica. I remember that when we reached Kleparz Yakov Moshe Hopen OBM turned to me and said, “these are the final hours of our lives. Let us escape from the procession towards the woods.” I proposed that to my father who replied that the same fate of all Jews will be his fate too. But Yakov Moshe, his wife, and two daughters departed the convoy, headed to the villages. I have not seen that family since. They must have been murdered by Polish villagers after hiding for some time in the woods.

Before the expulsion of the Turobin community there was also an expulsion from Modliborzyce and Janów. At the same time, a few young men from Janów and one from Modliborzyce. He proposed to the Judenrat to purchase weapons and we will be accepted into a group of partisans hiding in the Godziszów woods. A payment was made, but we did not see that man since.

Along the route of expulsion some 30 young men organized and we escaped to the woods. Near the forest which splitsŻółkiewka, we encountered a German army unit which opened fire on us. We dispersed. Along with a large part of that 30–man group, we returned to the expulsion procession. Part of the group regrouped and entered the Godziszów woods, where a group of 90 people convened. That group negotiated with a group of murderous Polish partisans, who took their money to purchase weapons and then murdered the whole group, except for two, one of whom I later met. I of course returned to the convoy and my family. The family continued to walk all winter [?] It was a cold day accompanied by pouring rain throughout all hours of the night. The rain added to our bad luck of the destruction and permeated the bones of the expelled. The convoy arrived wet and exhausted in the evening to Izbica [?]

The Turobin expellees were split up and placed in Jewish homes. That night, I was approached by Shalom Shabtai, a member of the Turobin Judenrat who told me the town was approved to be turned into a (judenstaat) Jewish town. Most of the local communities from Zamość to Lublin were concentrated In Izbica. It was said that from each community 40 people will survive and comprise the Jewish city. That was probably the German scheme, which demanded a large payment for Turobin to be included in that plan. I paid a large sum to the Judenrat as did

[Page 259]

many others. The Judenrat had to pay that ransom to a German villain who I think was named Abeyer. Yakov Feder and I then constructed a bunker in Altman's leather workshop.

The form of the scheme was that all those who paid the ransom and placed on a list would remain in the field and then returned to town. Early on Monday morning, the expulsion of the Jews from Izbica began to the train station outside of town. The expellees were commanded to sit on the wet and muddy grass. The victims sat there all day. In the afternoon, a command was issued to board freight trains. They began to recite the last names of those on the list to return home and instructed them to pass to the other side of the tracks. But many people not on the list followed those families and chaos ensued. The guards did not like that and they began assaulting the victims and shot some them. The SS men present shot those who tacked to distinguish between those on the list and others. That situation continued until it was announced that all Jews without distinction must board the train. After everyone boarded, they commanded that all young, healthy men exit the train. Truthfully, they did not want to leave the train so the SS entered the train and aided by blows from rifle butts.

The whole day of waiting, many commands were issued. Once it was commanded that all must hand over their money, and another command to hand over silver and Gold, and then that all craftsmen cobblers, carpenters, tailors move to a special section. That same time Shalom Shabtai offered me to become a carpenter but I refused and entered the train car. 1200 young men who were removed from the cars. We were gathered in a field and commanded to clean the area. Gold, dollars, other currency, and jewelry could be seen spread across the territory. Afterwards, the guards faced a machine gun at us and fired for 10–15 minutes. The screams reached high heaven. Those who fell, fell and those who remained were told to return to town.

On the way back to Izbica, the Ukrainian camp guard stopped me and ordered me to give him my boots which he liked. In their place I was given shoes with wooden soles which could not be walked in. I reached town and encountered Shmerrel Gells and Yakov Lev. They told me they had built themselves a bunker. Since I did not have shoes, I entered one of the Jewish homes to find shoes. In that house I found murdered Jews. I searched and found a pear of boots. But when I wore them I saw they had no soles. Shmerrel told me there was a cobbler not far from there who would repair them for me. Shmerrel gave me some money since I remained penniless. I told them of the events by the train station and they did not reply, since they did not know what could be done and where to turn. On the way to the cobbler, an SS man grabbed me by the neck and led me to a freight truck.

Among those on the truck was Avraham Kopf from my town. We were driven to a mixed village of Poles and Germans near Wysokie–Zamoyski. The Poles were cleared from the place and the farms were repurposed for the Germans. In place of two–family farms,

[Page 260]

one farm was constructed for a single German family. New homes were being constructed and we were tasked with construction. We were housed in a camp of small houses with kitchen. Of course, no food was given for cooking. Among the kitchen workers I met a friend from Zamość. The construction manager arrived the next day and designated me as a roofer. I was trained and began work. Avraham worked in building walls with heavy wooden planks.

The home we were constructing was for a German farmer. At lunchtime he called us and told us to eat from the potatoes cooked for the swine. Potatoes were already priceless at that time. I filled my appetite and kept some potatoes in my pockets for dinner. The farmer's wife was in Germany. One day, we entered the home and before we could taste the potatoes we met the farmer's wife. I heard her say to her husband, “you're letting those dogs eat? I will have you ordered shot,” and left the house. As I recall, the farmer turned white as snow after he heard his wife's words and was more nervous than we were. I did not forget to take advantage of the opportunity and stuffed some potatoes in my pockets. The German told us to leave quickly and we returned to work. I remember that everyone began crying about the potatoes we were barred from eating. At that chance I took out the potatoes from my pockets and we ate. One day as I returned from work I saw that Avraham suffered a face injury and his teeth were shattered. He explained that while working he lifted a heavy wooden plank which fell from his hands. The construction manager of the SS approached him and kicked him, breaking his teeth.

For a few days, Avraham repeatedly told me that we must escape the camp. But in order to escape we needed food, so we waited for the 800 grams of bread we received weekly. We received the bread portion, and I managed to steal some of the beets on their way to a sugar factory. On a stormy and rainy night, Avraham and I began to cross the camp fence. As we began to tread the muddy route, the camp guards noticed us and began shooting. Avaram's hand was injured, but we had gotten away. We walked all night. In the morning, we reached an area which Avraham did not recognize. We feared continuing traveling in the daytime so we took position in the fields, among the piles of wet hay. We began walking in the evening and walked through the night and reached a village. In one farmer's house we received food and then moved on to different acquaintance and stayed for the night. He also fed us, but then said we could not stay longer. We continued walking and reached a farm where we fond large piles of crops before harvest. We hid in those piles. We had one loaf of bread, which we lived on for three days. We heard noise near our hiding spot and thought we were discovered, But we saw people approaching a neighboring pile and extracting from it a young man named Velvel Kashizki. We did not know he was there, but the farmers knew. They extracted him and led him to the Gestapo in Turobin. After we had witnessed that, we left quickly that night, and continued walking towards the village of Czernięcin.

In Czernięcin, we encountered Yosef Kopf who supported us. I knew it was difficult for him to do so as the farmer must have demanded a high payment. I then decided to go to the front yard of my house in Turobin where my family had hidden gold and silver. One night, after I arrived in the yard and began digging, I saw a German was living in our house who awoke when I began

[Page 261]

digging. When the German came out to the yard I quickly left. The German saw me and shot after me, but I miraculously survived. As I ran I heard the guards in the town also began shooting and chasing me. I ran towards Czernięcin through the swamps, and the dogs they sent after me could not track me. After I returned to my former spot, I told Avraham I would return to Izbica, and Avraham stayed put. Yosef, who said he wanted to know what we would do there, joined me on my journey to Izbica. We reached Izbica after a long night of wandering. We then saw that the remaining Jews in Izbica were being gathered in the movie theater for one last expulsion. After Yosef and I saw that we left Izbica and returned to Czernięcin. A few days later, Avraham and I went to obtain food form a farmer who Avraham was acquainted with. On the way, we encountered Germans who shot at us. I left Avraham and escaped on my own.

I was headed to a work camp in Trawniki where my brother worked. I followed the route of the tracks of the freight train. I headed the wrong way and entered a lit village house, where there were five Poles. I asked for directions. The Poles were very happy to meet a Jew and invited me home, joyful they had found a “treasure” since for every Jew captured for the Gestapo they received several kilos of sugar and a bottle of Vodka. The farmers locked me in a room. At night, of course, I did not sleep. I contemplated an escape because I knew my end was approaching and my will to live overpowered everything. I began searching and found an axe in the fireplace. I was not sure I could battle five men with that axe, but they were sound asleep. I broke through the window with the axe and escaped. I reached Tarnow, where there was a guard inspection. They saw me and began shooting. I escaped into the woods.

I wandered the woods and survived off sorrel leaves and hackberries. A few days later I dared and approached a lone home near the forest. I knocked on the door. A tall farmer opened the door and said, “Jew, what do you need? Are you hungry? Please come in.” My frightful experience had impacted me, and I was too afraid to enter. The farmer fed me and said that in the nearby forests thee were Jews I could find. After a few days of hunger and cold, I swallowed the food to quickly and after I finished eating I could not move and my legs swelled immediately. The farmer was like an angel to me, he brought me to the attic laid me down and rubbed my legs with clean ethanol which was priceless at the time. That continued for 4–5 days and I then left to the woods with food the farmer had given me. For a few days I wandered the woods, unable to find the group of Jews the farmer had gestured toward.

One night, I heard braking branches. I moved towards the noise, and immediately fell into a pit. After I managed to leave the pit, I saw a campfire with a pot of chicken cooking. I sat, took the chicken, and began eating. Suddenly I realized I was surrounded by people. Those people were Jews who lived in a bunker. They feared me, scattered, and after they saw me up close returned. Those Jews did not have weapons. I stayed with that group several weeks until the snow period began. The group would purchase food in nearby Białki[?] village.

At the edge of the village I came across a farmer's house, whose granddaughter came from France and could not return. The grandfather and his granddaughter, a young woman of about 20, ran the farm. I occasionally received food from them and then disappeared into the woods. The snows began then and we constructed bunkers to hide in.

[Page 262]

One Saturday evening I went to the farmer to ask for food. The French woman told me, “Why would you return to the forest while it snows and freezing? Sleep here and in the morning return to the forest.” Of course, I stayed. Early in the morning she said, “I will cook some food for you. Eat and then return to the forest.” In the meantime, she borrowed scissors from a neighbor and cut my hair, since it was overgrown like a savage. The grandfather carried milk back from the barn. After the grandfather returned he said gunfire was heard from the forest. After it snowed, farmers had noticed footsteps and understood a group of Jews was hiding in the woods. It was told to the Germans who executed the group of Jews. Some managed to survive. I stayed with the farmer for the entire winter of 1943.

One night, I wanted to breath fresh air and stretch. I found two people laid on the snow, dying in the cold. They were brother and sister. I carried them to my spot in the attic but was afraid to tell the French girl about the event. Since that day, I shared my food with them, and of course we suffered hunger. One Sunday the French woman heard us conversing and she became aware of her new neighbors. She was not pleased by it. But she was simply an angel. After she learned of their presence, she constructed a bunker in the yard, and every time she learned Germans were to visit the village she notified us, and we scattered to the woods. One day, the French woman told us the Germans were on their way, and the pair and I left for the woods. We stayed there all day. I understood our friends would check on us and bring us food, since we were hungry. We stood guard and waited at the edge of the forest. In the afternoon she appeared and brought food.

We received notice that a group of Jewish partisans was hiding in the nearby forest section. That information was correct, since Germans placed a blockade on them and they relocated to our section. When they saw a stranger, me, wandering the area, they surrounded me, and brought me to their commander. It was a mixed group of Christians and Jews. There were 30 armed young men and some women and children. They hid in the forest without bunkers, as it was the spring (1943). They brought me to their camp and introduced the commander, a Jew from Kraśnik. His pseudonym was Adolf and his real name was Avraham Braun. He assembled that partisan unit. He was very active and organized, and thanks to him many survived. He was a talented leader, with a great sense of smell. He always recognized ahead of time when the Germans were approaching and hid the women and children ahead of time. In the span of months there were several clashes with Germans or Poles, also during food obtainment missions.

In midsummer, a Polish man arrived from France, formerly a volunteer fighter in Spain. He was sent to us to organize the partisans. He assembled 50 Poles and joined them with our group. Thus, we became a group of close to 90 men. Our first mission was to derail a freight train and obtain the weapons loaded on it. It was according to a notice we received that the train was carrying weapons to the Russian front. We did not have explosives nor tools to disassemble the tracks. We approached a point guarding the tracks. We overpowered the guard, obtained the keys, and disassembled

[Page 263]

the rails. We lacked experience, so we left the keys between the tracks so when the train approached the conductor noticed them and managed to somewhat stop the train, so from 30 cars, only 18 derailed. There was also an additional surprise: in place of a freight train with the weapons headed for the Russian front, it was a passenger train carrying officers from the German front headed to vacation. As we were in the middle of a mission we shot at the officers and killed 700 [?] of them. We lost one fighter, Yehoshua Klinbaum of Shestucka [?], the only one among us who operated a light machine gun.

Our hopes of obtaining weapons in that mission were in vain. Therefore, we attacked lone Germans, killed them and took their weapons. A war could not be waged with all that light weaponry, as we lacked the minimum necessary machine gun. That situation continued until the end of summer. Then our headquarters obtained contact with Moscow, and they sent us a commander named Vatzek (he reached us by paratroop) who brought with him a radio with a receiver, and a pair of Jewish radio operators, a husband and wife. Immediately after their arrival, we were supplied sufficient arms and ammunition. The Partisan group began to take the shape of an army, divided by roles and areas of operation. Our group spanned across a 50–kilometers–long territory. Our role was to destroy rail tracks, bridges, and police stations. I was given the role of communicator and received a horse for transportation.

That activity continued until the start of winter 1944. In that winter, we did not construct bunkers. Firstly, because we were accustomed to the unusual conditions, and secondly because we were always prepared for battle. In that winter we would construct protective nests from bushes and branches. Those huts were built only for protection from the snow, and we slept lightly standing up. The hut was built in such a way that our feet were immersed in the ground so they would not freeze. We lived that way and more than once we awoke covered in snow. Every morning, there was someone tasked by rotation to build a fire. We lit the fire at least 100 meters from where we lived. There were those who wanted to take off their boots to straighten out their feet but could not wear them in morning because the boots froze. If such a remover's turn to build a fire arrived, he had to walk barefoot in the snow. I was accustomed to bathe half my body in cold water. Almost every morning, I would open a frozen puddle with an axe and bathe.

I remember a mission we were on in that winter. Near Czarnocin there was a farm, owned by a man named Hoskowski. The farm was confiscated by Germans who placed in it a German manager. Our plan was to attack the farm. But as we approached Olszanka, a suburb near Turobin, we discovered a German police station. The Germans in the station held a long battle with us. We did not lose any men, but we had to retreat. We battled German forces almost daily.

In the winter of 1944 we battled Polish gangs, like the “AK” [Home Army] and ordinary gangs of robbers. We battled them more in the winter of 1943. That year we suffered much from those gangs, mainly the “AK”. I remember an event when three other Jews and I traveled in a sled while returning from a mission. On the way we met a larger group

[Page 264]

of “AK” who also traveled in two sleds. They blocked our path, and we jumped from the sled, prepared for battle. We were some distance away and the first to ask them to identify themselves. They replied they were “AK”, and we asked what group they belonged to, as we recognized their names. If we were the first to identify, they would have easily beat us since they had more manpower and firepower. We replied we were also “AK”. “If so,” they replied, “we will send a representative and you will too, for we are brothers.” The second their representative left we sent our representative who killed him with a Russian PPSh machine gun, and we retreated. We battled the Andki [?] groups for most of 1943 ns the winter of 1944. There were more groups like that in Janów and the Turobin area, but they did not dare fight us because they were few and at that time we numbered 6000 Partisans.

The Germans would siege certain areas of the forest, because they could not surround a larger territory as they did not have the necessary manpower. Thus, when we learned of a siege of one area our group would leave for a different spot. If the Germans were a small group, we went to battle. Usually in battles within the forest the Germans suffered losses because we hid in certain spots and sniped at them.

In 1943, we received no help from the Russians, because the Russians in those woods were mostly thieves and murderers. They were even worse than the O–Ka and were overtaken by a complete spirit of anti–Semitism. They were mostly Ukrainians. until the Russian captain arrived from Moscow, we knew the nature of a Jewish partisan in the woods. The captain's first order was that he did not want to hear “Jew” used as an insult as we all fight as one against a common enemy. Truly, since the day he arrived, we ceased to feel persecuted as Jews.

I recall than when the Polish envoy arrived from France, we were tasked with liberating a labor camp names Janisow. We stormed the work camp, killed the guards and offered the workers in the camp to follow us. We suffered heavy losses. In the end, the people in the camp did not want to leave, for many reasons, and only few followed us. They had lost faith in man, and feared that the Poles would murder them, since they heard many such stories and so preferred to stay in the camp.

After liberation, I met Yosef Kopf who said that after we parted ways near Izbica he still managed to hide for some time in the villages, and then returned to Izbica and was sent from there to the extermination camp Sobibór. He told me how he and his friend Leibel, son of the rabbi ofŻółkiewka led the uprising in Sobibór. They arranged for the craftspeople to invite the SS men in relation to issues with the work they had ordered and killed them when they arrived. Yosef and Leibel and another group then killed the guards and breached the fence. Some prisoners managed to escape and survived. After the war ended, Yosef Kopf returned to Turobin to recover his property and the Poles murdered him. The Poles murdered Leibel in broad day light on Kowalski Street in Lublin.

Our battles in the forest continued in the winter of 1944 until the French was front was opened. Then

[Page 265]

the Germans relocated two divisions from the Russian front to the west, and those divisions were tasked with exterminating the Partisan troops along the way

In the summer of 1944, we were surrounded in the forest for three weeks and fought the Germans during the day and by night retreated to a different area, then continued to fight. We received aid from the Russians who airdropped food and resources, in view of the German soldiers. In the three weeks of that battle, the German casualties reached 6000. We received those figures through the Polish press. During those battles, German headquarters was in a village surrounded by woods. We were located three kilometers from them. One clear day, a general went to tour the area in a caterpillar track vehicle accompanied by other vehicles. One of our men began to make his way towards the sled, but we could not understand what he was doing (at that time many lost their mind from exhaustion and war). The man approached the car and took the general's hat and briefcase. The general dared not move, and the man returned to us in good health. There were plans in the briefcase, and thanks to the intelligence recovered by the young man on his private mission we knew what was to take place, which prevented much suffering and victims.

After the battle we split into smaller groups. At that time, a fascist Polish group from the O–Ka approached us by messenger near Józefów. They proposed their help with an attack on the Germans. We agreed, and they received a designated strip. A few hours later, they surrendered without our knowledge. Suddenly, the Germans were on our backs and we decided to retreat by breaking the German line [?] Our group comprised 50 Jewish fighters. We had 23 wounded in that battle and we retreated to the Szczebrzeszyn area. While returning to the Otrocz woods we fought in one day nonstop from 6 in the morning to 9 in the evening. The SS had already penetrated our ditches [?] At that moment, an order was given for 40 Stalinowtzs [?] to go to battle. We were unaware that group existed. They had a Yeaktrow [?] machine gun with special plates [?] The group began a counter–attack and the Germans retreated. In that battle we obtained cannons. Until then we only had machine guns and submachine gun like the ZKM [?].

I remember that after that battle in Józefów we came across the forest keeper's house in the Szczebrzeszyn area. The guard housed us in the pavilion and left. We stayed to sleep. The next morning, he returned with two Poles. I knew one of them well; his name was Mokha and he was a pronounced Jew–hater, a leader of the O–Ka. The second he said, “hello, Mr. Zissmilkh,” I turned cold. I knew that in total we numbered 30 men and among us were 18 wounded and exhausted. Mokha the Pole approached me and said, “I see you are slightly disappointed to see me. But I must thank you and tell you that on your mission you have stopped the Germans from advancing for three weeks and killed many of them, for which you deserve praise.” He ensured we were brought food and drink and everything we needed, and supplied us transportation to the Otrocz woods. A group of fifty men formed and were given instructions to go on a mission in the Pławo area near Warsaw. A short while later, we returned to the woods in the Janow–Turobin area. We operated like that until the end of summer 1944.

[Page 266]

At that time, Lublin was already liberated by Russian forces. As the Russians approached our area, we stayed put. The Russians continued towards Germany. Most of the partisans were joined with the allied forces. I was enlisted in the Russian air force in a camp that formed near Kraśnik. A large number of partisans joined the Polish forces led by Wanda Wasilewska. Many were sent to the first battle on the Wisla River. Few survived that battle. The Wisla was red with the blood of the fallen who fought in that cruel battle. I served in the Russian military until liberation in 1945.

I was released from the Russian military in Lodz. Immediately after liberation, I married, and we traveled to Berlin. From Berlin we traveled to Munich. I stayed in Germany until 1949, when I made aliya.

Yehoshua Ben–Ari

Translated by Meir Bulman

One cannot speak of the Jews of the town without noting the Jewish families which lived in the neighboring villages and were an inseparable part of the Jewish community in town.

Many matters linked the two. There were family ties, business ties, and most importantly, there was the crucial attachment in spirituality; to the rabbi to rule on a question, the Rebbe to sit by his table and enjoy the presence of the Shechinah near him. The synagogue for prayers on holidays, the slaughterer, the circumciser, the matchmaker, the wedding comedian, and the wise Jew for advice, etc.

Thanks to that attachment and the warmth of Judaism, which accepted the rural Jew in his visits to town, he could keep going, at times as a lone man in a sea of gentiles; to trade with them, to have a home, and raise generations while preserving one's Jewish image.

Wondrously, despite the antisemitic condition which the Poles were afflicted with for generations, those village Jews managed to place roots among them, live respectfully, and for the most part were not harmed until the Holocaust. During the Holocaust the blind primitive hatred of gentiles towards Jews resurfaced. In a short time, one forgot everything, ignored friendship and good neighborly ties which were formed and improved for years. Aside from few Righteous Among the Nations, most of the rural population was hostile to Jews, be it actively or passively. The hatred towards the Jew was proportional to the danger he faced.

As one converses with a remnant of those beloved Jews, the impression is that the tragedy those rural Jews faced was mostly due to the Polish population which they lived within. While they were being aggressively targeted, the Poles were those who handed them to the Nazis or executed them on their own. For the sake of historical accuracy, it is noted there was also financial motivation: the riches of the Jew gathered by hard work could be gained only

[Page 267]

through physical extermination. A store, house, and sometimes land could be possessed. It can be said with near certainty that in theory the rural Jew, as opposed to the more urban Jew, would have a higher chance of survival if not for his neighbors who did everything in their power to fail him.

A while ago, we, a group of friends, realized the Yizkor book we are publishing would be incomplete if it did not include the beloved rural figures, only few of whom survived.

We were told of one man who lives among us and comes each year fir Yizkor who could tell many details, but feared divulging them publicly. At first, I did not understand that, until one night, we came to his house unannounced and explained the reason for our visit. He had no escape. For the sake of manners, he could not kick us out but it was clear he was doing everything to pass the visit without substance.

We did not relent. We enlisted his wife so she too would influence him to speak to us. Slowly, he agreed to speak to us on condition of anonymity. It was clear to us he was doing everything he could to forget the horrific events he witnessed, which likely will never let him rest. He has founded a new home, is admired, and has successful children. He is invested mostly in hard work to support his new family and ensure the children's future. But when he recalls the horrors, he separates from the present reality and returns to a dark world, all struggle for life without knowing why and for what.

He is from the village of Zdziłowice, about seven kilometers from our town. Unusually, that village had many Jewish families who worked in many fields: agriculture, trade, and crafts. They had their own synagogue and holy utensils. Almost like a little town. They had good neighborly relations with the gentile population, and suddenly, the Holocaust arrived. At first, they made due somehow. Until 1941, no drastic events occurred. People continued their lives and businesses with very few changes. The troubles began when the Russians began to battle the Germans. At that time, the Nazi plan for extermination of Jews was in place. Occasional horrors and killing took place.

In urban areas, decrees, limitations, and assaults increased. It was nearly impossible to travel freely. One night, he snuck into Turobin to visit his mother and other family members. He stayed the night. The next night, he dreamed his family back at the village was in danger. He awoke and snuck out without parting with his family and began running through the fields to the village. His dream became a reality, but he arrived after the tragedy. He found that a day before, a Gestapo unit came to the village, and in one fell swoop cruelly murdered 90 village Jews including his wife and two young sons. Those who remained escaped. In that state, unaware of the tragedy, he appeared in the village and sensed a deadly silence. A gentile friend he came across told him the horrible news and warned he must leave quickly. He could not.

[Page 268]

What does that mean, “leave quickly?” Until a few days prior he was a respected man, admired by his neighbors, safely living on his land, a husband and father, a man of certain wealth, how can he leave? Are his wife and children, to whom he said goodbye only yesterday, no longer living? No, it cannot be. He knocked on his neighbors' door. They feared to let him in, feared speaking to him. He met a young gentile who told him the place he can find the victims. He reached the kill field in the village, a large grassy field soaked with blood and scattered severed bodies immersed in the puddle. He had to find his wife and two sons. But how could he find them in such a valley of death? He suddenly noticed two hats he recognized belonged to his little children. That was sufficient proof for him. He took the hats and began to run quickly.

He returned to Turobin, and was kidnapped or handed over for compulsory labor. He was brought to the sugar factory in Klemensów near Szczebrzeszyn. He was not given food. He was commanded to sing [?] and work. He escaped from there too. With him were also Yakov Leib, Shmuel Itza'le, and Berrish Tregger. They ran under cover of night and hid in the fields. One day in the early morning, they were noticed and shot at. Shmuel was killed. Our man managed to reach Turobin (where else would he run to?) and stayed for a bit. The situation in town was awful. The restrictions worsened. It was difficult to leave and enter town. The local Polish gentiles already gave their opinion and guarded so that nobody escape his fate. Our hero managed to leave anyway, in the open, through the bridge. He was stopped by gentiles by the bridge. He fought them. They shot after him, but he already managed to escape and reach his village. He found there the same terrible graveyard. It was a year and a half following the slaughter. His mission was to find his brother who had also resided in that village from whom he had not heard since the killing.

There were a few more kind gentiles in the village and he managed to hide and survive through them. At the same time, he discovered that 36 others from the village survived and have returned to the village, or more accurately to the forest near the village, hiding and surviving with the aid of friends. It was rumored his brother was among them, but how would he confirm that and contact him? It was a difficult mission, but he succeeded. They began to discuss employment and life together in the underground. He needed a scale to weigh grain. He recalled he once loaned the scale to a gentile friend. He came to him after dark and requested the scale. At first, they were frightened by his sight and asked “Are you still alive?” after they saw he was not dead he was told to wait a bit. They began to prepare to exterminate him. He sensed it. He had no other way but to climb to the roof via a ladder and an entrance in the house. He was followed. He fought and could not be overcome. He was strong and fought for his life. That after he had been through nine circles of hell. The gentile was tired. He went to call for help after he locked all the doors in the house. He saw from a distance a murderer approaching holding a gun, a neighbor. A girl, probably a member of the household probably took pity on him and showed him a window through which he escaped. He ran and was chased until he reached the woods. He hid there a while until he joined a group of Russian partisans which he joined and survived.

That man could fill volumes with what he went through. Where is the talent that could faithfully describe those tragedies, the thoughts, feelings, and dilemmas?

[Page 269]

One wonders when seeing how strong the will to live is, and how strong a person is when facing danger and tragedies strongly inflicted one following another, and still finds the mental strength to build a new life upon the ruins of his first life which was exterminated so tragically.

Indeed, man is a hero and nature is so indescribably mighty, human language cannot describe it. A while later, we reached another survivor of the villages. He is Yitzchak Lander of the village Tokary [?], in the same area of the previous village. He is not interested in anonymity, but you feel that a broken man sits before you, who has been affected by time and the events in his external appearance as well. He is all white and elderly. He is quite old, suffers from illness, and in his eyes one can see a certain degree of apathy. He still lives in his world of memories, which likely do not relent. It is of no wonder after you hear his life story and the tragedy he experienced in the Holocaust.

Apparently, even after he succeeded, survived, and came to Israel, ready to build a new life, he married a second time and fell into the hands of a woman who tormented him until he managed to part with her. She and her family maximized the man's suffering threshold so that the natural strength of the villager we had come to know could not withstand and he shattered. He is now married a third time and our impression is that he has finally reached peace, even if minor, in the sense of “If he has found a woman – he has found good.” They live in silent harmony.

The man's story is not very different from the previous story. He was also a respectable homeowner in his village, was rooted in his land and the surrounding population whom he coexisted with for years. He frequented Turobin, and residents of Turobin visited him. He witnessed the horrors and tragedies of his family and others which will not be novel if I detail them here, and who can even describe all of it?

The main part of the story is the life of the escapees – those who hid in the forest near Otrocz. Otrocz was also a local village in the area where Jews resided. The Otrocz woods were known in the area as a thick forest and at times dangerous with robbers. I recall that from my childhood. Poland does not lack forests and the beauty of its natural scenery is contrasted with the human scenery.

The human scenery served to spoil the natural scenery. Those enchanting forests hid among their trees many big tragedies which will never be uncovered. There, survivors found refuge. There, they dug in the ground like mice or moles and lived in the ground in mold and fear of tomorrow. There, one had to suppress any sound of a moan, groan, or cry so not be discovered. There, people did not converse because the voice is traitorous. There they leaned a language of signals like they learned a lowly way of life. Nobody dared emerge from the ground in the daytime. In the beginning, 300 people lived in that manner in the Otrocz woods, spread across a territory of a few square kilometers. At night, people snuck to the nearby village or a close field in search of something to survive by.

The local gentiles sensed it. Even under such conditions, the movements of 300 people cannot be ignored. Occasionally they appeared in the woods accompanied by Gestapo. Or local murdering blackmailers and exterminate one kryjowka or another. kryjowka was

[Page 270]

the Polish name for such a dugout. Our witness said that in a relatively short time almost of the previous survivors were executed. 6–8 survivors remained, he among them.

It is difficult to describe what those few survivors encountered. More than once they desired the fate of those who were exterminated. How can a person live like a mouse in a hole, in the cold of winter, in the snow, the rain, without food and in fear of disclosing any sign of life? It is of no wonder that Yitzchak and the unnamed hero from the previous story became strong believers in God and religion and to this day live a stringent religious life, and raise their children in that spirit.

They find one explanation for their survival under such terrible conditions; the hand of God. With the help of God they survived and by his mercy they continue to live. Not long ago, our hero Mr. Lander contributed a Torah scroll to the his local synagogue. He funded the writing of the scroll which he led in a glorious ceremony to the synagogue.

He lived like that in the dug–out for three years and saw little of his surroundings. He remembers a gentile named Thomas Shchofk who was the fire commander in the village and saw him lead the Germans to the kryjowkas in the woods and helping in exterminating those living within them. According to his testimony, that same gentile also had a hand in exterminating the Hopen family, the family of Itamar, Mordechai, and Yehoshua who are here with us.

Those woods were also the den of combatants who were defectors from the Russian military or those who had not managed to retreat when the war between the Russian and Germans erupted. They lived as nomads and murdered for survival. They did not have Jews in their ranks, unless they could aid their war for survival.

Mr. Lander recalls that among those hiding in the woods were the families of Shalom Fleischer, Zalman Fleischer, and other families whose names he cannot recall or did not know their names.

The extermination in Tokary[?] began on the first night of Selichot in 1942. 57 Jews were murdered then. In Otrocz, 20 people were murdered on the 1st of Elul that same year. In Zdziłowice village on the second night of Selichot, 75 people were murdered as well as in Dzielce [?] and the other villages. Those were the villages to the north of Turobin. On the road to Janow–Lubelski there were many villages throughout the whole area where many Jews lived such as Tarnawa Szewnia [?] and more.

The town was in that sense the tree trunk from which the villages branched. The Germans in their diabolical plan began with cutting those branches, and only later cut the tree down and exterminated the Jews of Turobin. According to Mr. Lander's testimony, the extermination in town began when 12 Judenrat men were forcefully removed from the town and murdered in cold blood near the brick mill. Eight days later, the final extermination of Jews plan began, and others testify as to that.

May the souls of the martyred victims, the pure and honest villagers, be bound in the bond of life, in the bond of the pure souls of Turobin from which they drew their strength.

[Page 271]

|

|

|

|

| These pictures were found in the ruins of the Jewish town after the Holocaust. By all indictors this was on the eve of the third and final expulsion. |

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Turobin, Poland

Turobin, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 16 Apr 2021 by LA