|

|

|

[Pages 249-260]

by Shimshon Meltzer

I had around ten teachers in our town, the town of Tluste, and from each one of them I learned something. All of them were honest G–d fearing pious Jews, versed in the Torah and distinguished scholars. They did not perform their work, the work of the Lord, by fraud. All of them tried hard to teach the Torah to their students and to give them something from themselves. But what they had for themselves and how much of it they were able to pass to their students – in that they were very different from each other. And this is the reason why only some of these teachers remained carved in memory. Even this list is short and slowly fading, but the memory of others is hidden in my heart. I remember them, their teachings, their customs and habits, with love. I even remember with fondness their small–talk, and my soul is beating in me when I bring their names on this page.

My first teacher was called Moti Kutsh,

his old house was hunched and leaning to fall,

I was brought to him on a gloomy autumn day

to start the Aleph–Bet with sound and song.And it happened when I approached the rabbi with my Sidur

to read A–Ba–Ga, Da–Ha–Va in a whining voice,

the writing looked elegantly decorated to me

and each letter looked defined and pleasant to me.Everything looked glowing and full of light to me,

like the colors of a rainbow extending to the

heavens on a rainy sunny day……

because I discovered the Sidur through a tear.

I was around the age of four and a half when I was brought to the home of “Moti Kutsh.” I probably studied with him for two “periods,” the winter–period and the summer–period, until the eruption of the First World War. My first “period” with R' Moti Kutsh was rewarded with a wide and detailed description in my book “Aleph” and, to be truthful, I must admit and inform that all that I described in that book I really remembered from the “Heder” of R' Moti Kutsh. I was too young when I started to study in his “Heder” and I can't remember all the details, the order of studies, the recess and the games. Most of the information in “Aleph” is from a later observation in the “Heder” of R' Dudi Pfeffer, who was in fact the most “important” teacher in our town with whom I was not rewarded to study, “by miracle,” because of the war and the escape from the town that lasted for almost three years. His class was in the “vestibule” of the great synagogue. A wide and big room, its floor was paved with stones and it did not have any windows. Air and light streamed through small windows under the ceiling and through the entrance door when it was opened for a few minutes. There were many students, around forty in number, and they were divided into a number of “classes” according to age and their degree of knowledge. Each class sat next to its table and “repeated” in a chorus what the rabbi ordered to “repeat” in a great confusion of voices. I was around the age of fifteen when I stood in the same hall, looked at that “Heder” and everything that was happening there with a “critical eye,” in order to describe it in a “written essay” for my Hebrew teacher, Mr. Mordechai Spector. Even today, I keep this work in a notebook and I wonder about the measure of ugliness and wickedness that I invested in that description. It was full of darkness and gloom, and there wasn't even one spark of light in it. I don't know who was “responsible” for this hostile “vision”: my Hebrew teacher, who tried with all his might to open my eyes, and the eyes that were opened – were opened to see that, or maybe it was the writings of Mendele Mocher Sforim that I read continuously when I was sick for a full month. The continuous non–stop reading provided me with the full treasure of Mendele's vocabulary, and it is possible that it directed my eyes to see everything through Mendele's eyes… and the sight, as I said, was darkest from dark. My ancestral merits probably stood for me when I came to describe my first “period” in the “Heder” in my book “Aleph.” The “sights” that I saw “behind my tears” were illuminated by the light of mercy, love and kindness.

In the “Heder” of R' Moti Kutsh I learned to read and to pray. When the war erupted, and I was around five and a half, I was already familiar with the Sidur and the proof for that: when we escaped from Tluste to Horodenka we stopped in Uścieczko by the Dniester River. The bridge was already burnt and the ferries that were promised by the military had not yet arrived. There was a nice forest near the river. The Jews wrapped themselves with their prayer shawls and the young men adorned themselves with their Tefillin and stood to pray Shacharit [morning prayers] in the forest. At the same time, I held my Sidur in my hand and knew how to follow the congregation and the cantor.

The meaning of the name Kutsh is not completely clear to me, and, when I asked my landsmen, they were not able to give me a clear answer. It is possible that the word Kutsh is a distortion of the word Kortsh, meaning, root, trunk or dwarf, and the rabbi was called by that name because he was short. And, if so, his name was close and similar to the name of a teacher greater than him, and he is Yanush Korchak. The meaning of his name is simple: Kutsh – carriage, and it might be based on a story about a trip that he took, or maybe one of his family members took, in a carriage of powerful lords…

Clearer and safer is the name of my second rabbi with whom I studied in the town of Zaleszczyki. We arrived there via an indirect route, through Horodenka. We stayed there for a year and a half during the days of escape and exile, and out of fear of the Cossacks.

The rabbi was called Teshapki Melamed by all and, as we know, Teshapka means a hat in Polish and Ruthenian. And here we need the saying of our Sabra sons: why was he named Teshapki?

Why – hat? But, it is possible to assume that also this title was probably based on a real event or on an event that could have happened, such as when the rabbi entered a government office and the Austrian clerk, a Pole who hated Jews, berated him because he did not act quickly to remove his hat.

He was an easy going person and I can't remember if he ever scolded me or another boy. There were around twenty of us. I see all of us sitting next to a long table laid with the best for the feast of Lag Ba'omer. At that time, Tluste was in the Russian zone and was wiped dry from everything good but Zaleszczyki, which was in the Austrian zone, was blessed with the best. The abundance was also present in our “Heder” – figs, dates and different kinds of candy. Two of my cousins studied with me at Teshapki, and were partners to the same feast. My first cousins: Michael Meltzer who now lives in Haifa, and Mordechai Sternkar who now lives in Beit–Shearim.

When the front got closer to the Dniester, we were forced to escape from Zaleszczyki to Czerniowce [Chernowitz] on the first day of the holiday of Shavuot. I ran to my rabbi's house to collect the three pilgrimages “Mahzor” that I left there. I was very sad for the “Akdamot Milin” [a religious poem]. Such a beautiful great poem and the first that I learned by heart. I was not rewarded to read it in the synagogue on that day. Exactly at the time that “Akdamot Milin” was read in the Dripaltikyt Street synagogues in Czerniowce, we entered the same street together with other escaping refugees sitting on top of farmers” wagons. The wagons were loaded with our belongings, women and children sat on top of the bundles and the men walked behind them…

Additional pain was caused to me by the special lovely poem “Yeziv Pitgam” [Aramaic hymn in praise of the Torah] that I also knew by heart, but without fully understanding it. Now this short song is totally “wasted” on me. Will my father have the time and the will to open the Mahzor, to test me and listen to me reciting the entire poem by heart?

This short poem was “special” in my eyes since all of its lines ended with the same rhyme: “Rin”, and the repeated endings sound like rin–rin–rin–rin, which were lined one under the other at the end of the page. In my eyes, they looked like water dripping from the edge of the roof, one drop after the other, like a string of beads. They sounded in my ears: rin–rin–rin, meaning: tif–tif–tif, drip, drip, drip… you the reader, don't wonder that the string of beads sounded and looked that way to me, the child. This vision and sound already had a base and a root in R' Motie Kutsh's Heder. When we started to study Parasht Vayikra from the Chumash, our group read it and translated it to Yiddish in a loud voice: “Ben–Bakar” [a calf] – “A Yengel Rint” meaning: a dripping boy. This was closer and clearer to us than the correct translation: “Ben–Bakar” – “A Younger rind”. The word “Rind” was not common in our language, and we did not assume that the words “Rinder Fleisch” (beef) that our mothers said was somehow connected to “Ben–Bakar” – “A Yengel Rint”…

Teshapki Melamed's Heder was located in his apartment at the end of the road “on top of the mountain”. Many years later, when I was a grown boy and traveled from Tluste to Kołomyja, I turned to Zaleszczyki to show my companion the few places in the city that were connected to my childhood memories. Only the Dniester remained mighty and impressive the way it was, but the rest of the places had changed their look and size. The big buildings of my childhood became smaller in my adolescence and now looked smaller and shorter. Long distances shrank to a few steps, the “tall mountain”, where Teshapki's house stood was a slope. I found only one small closed alleyway. The rabbi's house did not stand on “top of the mountain” but at the end of that alleyway that indeed rise up on a hill.

The rabbi was no longer alive, but the great experience was alive in me with the same strength that existed in me during that “time” in that “Heder.”

One day I returned to the Heder after a lunch break and, behold, a group of Jews dressed in kapotes [caftans] with beards and side locks were struggling with a saw and a hammer, nailing unpolished white boards together, and building a kind of long box. A few of my friends from the Heder stood around them in a half–circle, and one of them whispered to me: “they are making a coffin for a dead person… the old man in that house died….”

Not too many minutes passed and the dead man was taken out. His bent body was wrapped in shiny shrouds, and he was placed inside the coffin. I escaped like a shooting arrow, ran back home shocked and terrified, but I did not have enough energy to run inside the house. Breathing and exhaling I ran into the tobacco store that was owned by our best neighbor, R' Yedel Kutner. He was a wise Jew who liked me and talked to me a lot, and his jokes and candy were always waiting for me. What happened? Why are you so pale? He asked me and pressed my head into his chest. I was only able to emit one word – “I saw”. “What did you see?” – he asked. “A dead person” – I answered, and started to cry. “Ha! the old man next to your Heder?” – “yes, yes”, “and because of that you cry? My little fool! He was a very old man, a hundred years old or maybe more, and he died a righteous death!”

A “Righteous death?” What is it? His words did not explain much and I continued to cry. I did not cry for the old man. I saw him many times sitting on a bench next to the house, warming in the sun and “chewing”. “What is he always chewing?” I asked my friends. “He is chewing nothing and he does not have any teeth”. But he was alive, alive, and now I saw him dead. They placed him in that coffin, and they put two unpolished boards on top of it, and they took a hammer and nails to seal him inside. With nails…

And so, I discovered death for the first time, and the childish heart cried from fear and knew why he was crying and why he was afraid. He probably knew that in a year or two deaths will appear in his family, his brother – far away, and his mother – very close. “I was nine years old, still a child, and death – doubled –looked straight deep into my eyes”.

The days of war and “exile” in Horodenka, Zaleszczyki, Chernovitz, and Sasów skipped me to the Heder of R' Dudi Pfeffer, which was crowded and very noisy. So I moved to the Heder of another teacher, who was the opposite of R' Dudi: thin and delicate, feeble and quiet. I don't remember his name, but I remember him and his wife the Rebbitzin: a white scarf was always tied to her head, the ends of her loop snuck out from under her delicate chin like two little wings, and her beautiful small face was made out of very thin wrinkles, like an apple that ripened late in the autumn. The rabbi's face was also shriveled and wrinkled, and his very thin voice sounded like his wife's voice. His wife's face was clean without the signature of a beard, but the rabbi also lacked a beard, not even one hair! Not that he shaved it, G–d forbid! but because he never grew a beard! So the children swore and testified, and said that because he did not have a beard he also did not have children.

I don't understand the connection between a missing beard and the lack of children. But I feel sorry for this small couple, who lived in peace and loved each other like a pair of doves. It showed when the Rebbitzin brought the rabbi his daily lunch in a clean basket. She waited until he was done with his meal and took the empty dishes back home with her in the same basket….

His Heder was in the Tradesmen Synagogue which was also located in the great synagogue. The entrance was through R' Dudi Pfeffer's Heder. There were few students there and the studies were conducted in tranquility and calmness. The students bragged that their rabbi never hit them and they never heard a word of scolding from his mouth. On the contrary, the students of R' Dudi Pfeffer claimed that their rabbi talked in a woman's voice, his face was a woman's face, he did not have a beard, never had one and would never have one… and my luck played for me, and I was not brought to that rabbi, but to the Heder of R' Ahron the Melamed.

R' Ahron Goldhaber was not a native of Tluste, Horodenka or any other town. He came to our town after the war and immediately earned the name of a good outstanding teacher. His “Heder” was located in the big house of the Mani Gertner family, near “Gvitzsa” hall in old Targovitza. The big room also served as a synagogue on the Sabbath (since most of the synagogues in town were destroyed). There were three classes there. The largest class had four or five grown up boys and they only studied Job for two hours in the afternoon. The melody of Job's complaint is still ringing in my ears which were always open to receive everything enticing. R' Ahron read it with affection, as though he was listing his own complaints to the ears of his older students. The melody came from the bottom of his heart, and entered my guts and my kidneys despite the fact I understood very little of the contents. I greatly doubt that a small portion of that lamentation and joy, argument and flurry of emotions, are still echoing in the ears and the hearts of his five older students… Three of them are still alive and live in three different faraway lands. They were too old, too experienced in the fearful events of the war to be able to comprehend the talk of Job that was mixed in R' Ahron Melamed's crying soul…

The young class was also small, five or six boys. Besides the Chumash with Rashi we also studied Yehoshua. But I did not stay in that class for many days. There was an older boy in that class, in the small class, probably two years older than me, but his brain was weak. The rabbi told me to “repeat” the chapter that we studied in Yehoshua until he understood it. I “repeated” it with him once, twice and three times, but he was not able to understand it. On the next day, when R' Ahron came to test us on this chapter, that poor boy stuttered and did not know the meaning of the words. When my turn came to read and explain, I looked at the rabbi and without looking at the book I said one verse and translation only by heart, since I had memorized it from the repeated reading with that boy. R' Ahron heard a number of verses to the end of the chapter, thought for a moment, and said to me: you are not good. I looked at him with wonder and I was ready to start crying. I was sure that he was not going to let me be a “repeater” to that boy, but R' Ahron repeated and said: you are not good for this class, move to that table.

And so I moved to the middle class, the big class. Around twenty students sat next to the long table, and matters were brighter and happier there. In “Pasuk” [a sentence in the bible] we studied the Book of Isaiah (at that time I was not able to tell the difference between Isaiah and Joshua, but years later I decided to correct the distortion). In the Torah: at first I studied Parasht Vayechi with all the “details” about my second “self,” about “the brothers Shimon and Levi” and the proof that only they, Shimon and Levi, plotted together to kill the whole city of Shechem and sell their brother Yosef… all these matters were lofty, exalted and royal. Yosef was second to be king. His two sons – great heroes. Yehudah – strong and mighty and the father of future kings: “The kingship will always be in the tribe of Yehudah” …and the “family members” were also pleasant and friendly, they also liked Yosef, as it says: “He was an assistant to the sons of his father's wives, Bilhah and Zilpah”… we are forced to say against our will that: “the brothers Shimon and Levi” were of the same opinion… but for the sake of the truth – the childish heart hated them. On the contrary, the two brothers were heroes, carried weapons and knew how to frighten a town full of gentiles – it was a pleasant and lovely thought and I wished I had two brothers like them!

On the Sabbath I'm tested. I know all of Parasht Vayechi with Rashi, all the way to the end. And I know the verses by heart – twice as much: in Rashi's short and condensed language, the holy language, and also in my rabbi's Hebrew version with the special melody. And the childhood voice is ringing like a bell and blows like a flute, and fills all of our “front room” …..

R' Ahron liked me, and also his tall wife with the delicate face, the Rebbitzin, showed me great affection. There are two girls in the house and now a boy was born. Tomorrow he will be circumcised and R' Ahron is calling me to help him with a matter of holiness: the foundation beam of the old house where the Heder is located, a beam that is protruding from the wall and crumbling from old age and rot. He is taking a piece of broken rotted wood and crumbling it slowly, slowly to a fine powder. Later, he sifts it with a thin sieve – and the brown–red “flour” will be thrown on the circumcision tomorrow to stop the blood… and the baby, thank G–d, will grow up and become a boy, and the boy will become a teen, and the teen will become a young man. And he stood before all the horrors of the war and he is now in Israel, and he is, Avraham Goldhaber, May he live.

How good it would have been if they had allowed me to study with R' Ahron for three–four periods, but the Kingdom of Poland thought and found out that R' Ahron was needed to enforce its military power and drafted him to one of its forces. R' Ahron Goldhaber was his name, but he did not have gold and he did not have money to redeem himself from the army, and the best Heder in town was scattered among other teachers. How did the family earn a living? At that time, I was too young to be interested in this matter and investigate it.

Probably at the same time the lot fell on me to become one of R' Asher Kurtzer's students. Before the war he was a teacher in Baron Hirsh School. After the war he lived in a building next to the former school. That building was fully occupied with those who returned to town from their “exile” and found that their homes had burned down. R' Asher Kurtzer had a number of occupations. He became a cantor, a Mohel, and a teacher, but all of them did not provide an income to his family and did not drive the poverty away from his home.

R' Asher was not a “Melamed” [a Heder teacher] but a “Teacher”. He had few students and taught in his home, a one–room apartment. From all that I learned from him I remember only The Book of Proverbs. I remember that he did not explain the meaning, wisdom and moral of the verses. He translated them in “Germanit” Yiddish (probably using a book of “commentary” that he owned) and, to our ears, his translation was something that needed a translation and an explanation, therefore:

The clear reasonable words of Solomon – did not attract my heart,

the rich moral from which he collected wisdom like women, did not please the lad,

but what wisdom did I earn in his home, from extreme poverty,

from the few blessings and the many crafts of a teacher, cantor and a Mohel….

“From extreme poverty” – G–d forbid that you think that it is a figure of speech, out of the need to find a rhyming word for Solomon. The poverty in that home was elevated and lofty; it was an elegant aristocratic poverty. The speech in that house was pleasant and noble. On Thursday, market day, the woman and the man calculated what they needed for the Sabbath. This is missing and that is missing, but probably only an accidental shortage, a temporary shortage… and indeed, it was only “temporary”. After a few years the two boys grew up and helped to provide the family, if not with abundance, with honor.

R' Ahron Goldhaber was taken to the army in the middle of the summer and the students scattered among the different teachers until the end of that period. After the holidays, R' Shimon Gabai from Estisheski was brought to Tluste. He was an outstanding Gemara teacher. The “Pasuk” was pushed to a corner, and even the Chumash with Rashi were pushed to Thursday afternoon and Friday morning. All the days of the week were dedicated to a page in the Gemara.

I don't know what moved R' Shimon to choose “Masechet Ktovot” and start with the second chapter.

We were children of war, and the matter of a woman claiming her marriage contract after she became a widow, or divorced her husband, did not stimulate the souls of 18 teenage boys who sat around the table in the “Vizshnizer Kloiz” (the synagogue of the Vizhnitz Hassidim). Surely, in a week, three or four students (myself included) had a command of the Gemara page and in the negotiation that was strange to us (it was winter outside, the bells rang on the horses' necks and snow fell and covered the town with a white scarf). There were a few sweet words and, ever since, their good taste remained in our language: the woman who was widowed is simply a woman who became a widow, a veil is the scarf that a bride wears, and the “mouth that forbids is the one that permits”, a great basic rule that always stands for me in the time of need. And, above all, the “Migu! ” [a Talmudic claim – why do I need to lie] a concept that your tired young brain can't understand and learn the meaning of, but after you earned it for yourself – it is yours forever and you treat it like a treasure.

R' Shimon was required to prepare a test for the Sabbath, not only for the three or four “good heads,” but also for all the students. The poor man worked hard – and all for nothing! Every Thursday, with great sadness and devoted pain, he repeated in a red weak face: you study and study and study, and when you arrive at the end of the matter – there is no one at home! (pointing his thumb up).

Of course, the word “children” was directed at those who did not know and not at the three or four who knew. But, R' Shimon was not comforted with the few “good heads,” and every week he felt sorry again for the failure of his intermediate students. What else could he have done for those students?!

The boy Munya Gabai brought him to destruction. Munya was the rabbi's brother's son, an orchard tenant who lived out of town on the road to Zaleszczyki. Munya was a wild lad and his brain in front of a Gemara page was like an empty bottle that was very well plugged. It was opened like a pigeon coop and all kind of “ideas” and inventions flew out of it. He entertained the other boys with them and distracted them from their studies. In winter, the rabbi left the “Vizshnizer Kloiz” with a big checked woolen scarf wrapped around his head and his back, exactly like the scarf that women wrap with (and he was the only man that I saw wrapped in such a scarf), and under the scarf it was possible to see his bent back. I knew that, because of the chill outside, the rabbi was leaning and wrapped in that way, but I could not put my feeling aside that the troubles that Munya brought on him bent his back……

A few years later, after Munya drowned in the water reservoir near the mill on the road to Swidowa, he was taken by a cart to the home of Dr. Albin, as though he was able to revive the dead. In my heart I was sure that it was a punishment from the heavens for the grief that he caused his uncle, R' Shimon Gabai, but I felt that the punishment was too severe…

R' Shimon had another relative who studied in our Heder and his name was Vali (Avraham), the son of Mordechai Gabai. Vali was one of the three or four good students, not with the power of his quick understanding, but with the power of his great dedication. He was a tender good teenage boy. He was also a partner to the great grief that his rabbi and uncle R' Shimon suffered, from the pranks of his cousin Munya. In order to compensate for that – he studied with great dedication. A few years later, when we grew up and the town's youth started to think about their future and broke their way into the “big world” and for education – he remained the only student to sit in Beit Ha'Midrash, and he studied the Torah with the dedication of a real diligent Yeshiva student, the way it was done in the old days. His father and all the members of the town expected greatness from him. In secret they also told wonder stories about the charitable deeds that he performed with the daily meals that they brought him in Beit Ha'Midrash, and the pocket money that his father gave him.

He was a year younger than me, and his “comprehension” was slower than mine, but in the two or three years after his Bar Mitzvah, at the time that I was busy in different works and read a lot of secular books that I found in the Zionist library and in the Hebrew School – he sat from early morning to the late hour of the night and studied, and studied, and studied – the Gemara. During those three years he became a real diligent Torah scholar, and I, what did I achieve – I filled my belly with Shmuel Leib Gordon, the “Hebrew version” of Kerensky, and all kinds of books that were not “religious books.” I knew that his way was better than mine, but I did not have the power to change my mind. My road led me to Lwów [Lemberg], but he remained in Tluste, in Beit Ha'Midrash, studying diligently on his own. And his road was only a few hundred steps, in the morning from his father's house, across the bridge to Beit Ha'Midrash, that the rich woman, Mrs. Rivka Braksmayer, built, and at night he returned the same way. For that he crossed twice a day and he did not know any other way.

But he was destined to travel once all the way to Lwów on his last journey. And in spite of the fact that his father's home was close to Tluste's cemetery – it was forecast that his tender and graceful body would be buried in the Yanovski cemetery – ten full years before the place became a death camp and a burial ground for the Jews of Lwów and the extended area.

Even he, the good, innocent and honest, like his cousin Munya who drowned, was taken to Dr. Albin – to his clinic in Lwów for an appendectomy. The matter became known to me in the evening and when I hurried to that clinic the next morning – I already found him lying dead on a high bed. Blood was flowing slowly from the oilcloth, dripping from the bed to the floor and accumulating in a small puddle. He arrived to Lwów too late and died during surgery or shortly after it.

He was around eighteen when he died. If he had died in Tluste, probably the whole town would have come to accompany him, and the town's wise students would have given him a great eulogy. Now that he died in Lwów his funeral was arranged in haste. The funeral left the Jewish hospital in Rapaport Street and the coffin was not carried on the shoulders, but transported on a Hevrat Kadisha cart – no one eulogized him or cried for him, no one walked after his coffin besides the members of Hevrat Kadisha and a few poor people who accompanied them for the mitzvah and for the hand out. My arm was inside the arm of his unfortunate father, R' Mordechai Gabai, and we walked heavily after the cart, along Rapaport Street, and the father was not shouting and was not mourning, but he whispered all the time: “Shimsheli, you are the only one who knows who I am leading to lay inside the grave,” and I only shook my head and I was not able to say even one word, since my tears choked my throat.

On Passover eve, R' Shimon Gabai returned to his town of Uścieczko and never returned to us. Maybe he missed his family members, or maybe he longed to see his tiny little town that resided by the mighty Dniester. And maybe he did not long for the Dniester that rolled its great waters with a broad royal serenity, but maybe for the little tributary, the Dzhuryn, that rushed with a great noise to the Dniester? since this Dzhuryn passed not far from his home. Once, about seven years after I was his student, I found him standing on the small wooden bridge above the yellowish tributary looking at its stormy water after a summer rain that fell on that day. “Shalom Rabbi!” – I shouted from a distance, he greeted me, immediately recognized me and called me by my name, but he did not shake my hand, probably not to embarrass the young woman who walked with me since he was not able to shake her hand. But the rabbi did not abstain from looking at her, at this young woman, and asked if she was my “bride.” In order not to confuse the answer I simply answered “yes.” The young woman blushed and I think that R' Shimon's face came alive. At the same time, I thought that he was not an “idler,” and perhaps in his youth he read Schiller's poems and Goethe and Heine, and the proof of the matter: when he was kind to us during class, he kept on promising us that if we would be good children and also study hard in the next week, he would pay for the favor with a favor and teach us German grammar. He never reached the point to keep this promise, and we also did not crave that he would keep it – these terms looked strange and magical to us, and were above our understanding, but we were sure that he was able to keep his promise if he was able to do so. Now I said in my heart. Is it possible that he knows German grammar without knowing a little German literature or poetry?

For the summer period, R' Shimon Gabai, son of Muni Gabai, came in his place. They resembled each other in their height and in the same shiny red face, but while the father's face was adorned with a beard and his head with side locks – the son's face was smooth and it looked like it was covered with oil. I don't know if the son removed the hairs of his beard with some kind of a “potion” that the Jewish religious laws allow to use, or if he was shaving it with a real razor. The second possibility was probably closer to the truth. If not – from where did all the frequent injuries come to his face? And if so, how did the Heder boys' fathers ignore it? since all of them were pious and most of them were Chortkov or Vizhnitz Hassidim.

The “Heder” was no longer in the “Vizhnitzer Kleizel” but at the home of Mrs. Leah Stupp, in a room that she leased cheaply for that purpose since her son, Muny, was also one of the students. Heaven Forbid! Leah Stupp was not a widow. The head of family, R' Izik–Leib Stupp, was a Vizhnitzer Hassid, a scholar and a cantor with a stylish pleasant voice. But since Mrs. Leah was wise and knowledgeable, she was not only a housewife but also the active soul in the fabric shop in her front room and in her egg business on market day – the whole family was named after her.

The main difference between R' Shimon Gabai and his son, Muni Gabai, was only in the fact that the father was called by all “Shimon Melamed,” but his son was called from the beginning and also during all that “period,” “Muni the Teacher.” And what did Muni the teacher teach us? Maybe he came to keep his father's promise and really teach us German grammar with all the six tenses in it? Or maybe he would start teaching us the books of the prophets according to their order, from first to last, with Rashi, with Mezurut and with the commentary of Rabbi Meir Leibush ben Yehiel Mikhal? Heaven Forbid! It did not come into his mind. He was not brought to Tluste even for that! His father, R' Shimon the Melamed, taught us about a woman who became a widow and she was demanding her marriage contract, but the son Muni the teacher, taught us the matter of bringing a divorce across the ocean, and the need to declare who wrote it and who signed it! If Muni the teacher had pointed to us on a certain map of Eretz–Yisrael (one of those was already available at that time in our town, published by Amkroyt et Freynd in Przemysl, since the days were after the Balfour and the San Remo declarations!), they would have lit our eyes saying: here is the land of Binyamin and the city of Rekem, and here is the city of Acre (still there today), and here is the city of Ashkelon. R' Yehudah spoke about these cities in the Mishnah: “From Rekem to the East, and Rekem is like the East; from Ashkelon to the South, and Ashkelon is like the South; from Acre to the North, and Acre is like the North” – unmistakably the matters would have been clearer in Masechet Gitin [a tractate of the Talmud devoted to the validity of the divorce document and how it may be written and delivered]. But Muni the teacher did not show us any kind of a map, did not bother to explain why R' Yehudah was setting boundaries only in the east, south and the north, but not in the west. He only bothered himself with a question of the witnesses, who signed it – i.e. to effectuate it, and the witnesses who handed it over. We were not attracted to this problem, and I think – also the heart of the teacher was not attracted to it. His heart was attracted to something else

In the same summer, Ms. Miriam Rosenbaum visited our town. She was the daughter of R' Shenor Rosenbaum who is “Shenor Melamed.” Only my friends and I knew of his good name, but we were not rewarded to see his face and study the Torah from his mouth. This Miriam was well educated and spoke Hebrew in the days before the World War. She even founded a Jewish Zionist society in our town for women who studied Hebrew and Jewish history. Now, she came from afar (from America!) to visit her town, Tluste, and she was staying at the home of Leah Stupp, the home where our Heder was located. Besides the fact the Miriam was perfect, she was also a beautiful woman. And the soul of Muni the teacher longed to talk to her! He was not able leave his students, approach her directly and start a conversation out the fear of what the students and their parents would say! He did not dare to talk to her or take her for a walk in the streets or out of town, from the fear of what people would say! So he sent her small letters, small folded notes, and he used me as his messenger to deliver them. And I would leave the room and walk to the other room, hand the small letter and wait for a written answer. And at the same time, I enjoyed the glowing face of that Miriam. And at the same time Muni the teacher apologized to me and said while his red face was getting redder: All his intention with these letters was to revive his knowledge in the wisdom of Gabelsberger's Stenography since these little notes were written in Stenography letters and good things come in small packages…

Miriam is reading and smiling, replying what she was replying, also in Gabelsberger's Stenography, and telling me that she likes me. Is it not something! Miriam the scholar, who knows how to speak Hebrew! But she is not the only one who likes me. Also the girls my age and the girls who are older than me by a year or two, who come to Mrs. Leah Stupp's store to buy a piece of white fabric and print a nice sample for a Sabbath tablecloth – they also like me! For what reason? Because, all the nice samples are drawn in advance. You copy them from a paper that is pierced with tiny little holes by spreading blue powder on it and spraying some kind of a liquid to set the color so it will not be erased. But, it is not the same for monograms – those you have to draw for the name of each girl! And I'm the one who knows – the one who knows everything and knows from where! Muni the teacher turns an eye on the fact that I disappear for hours from the study table. He probably trusts my good “grasp.” And I stand and draw a monogram, a great letter for the name of the girl, curly and intertwined with her surname. To complete the art work I decorate them with leaves and blossoms, and the girls stand around me and look at my work with wonder, and one of them, Feigale' the beautiful (the wife of Zechariah Krizler, Canada), is bending over me and actually leaning on my back. Her golden braid is gliding on the left side of my neck and her hot breath is patting the right side of my neck, and under my hand the blossoms are blooming for the completion of her monogram…

The monograms and the golden braids of the beautiful Jewish girls sweetened my summer days, and the teacher Muni did not scold me – and for that I remember him well!

From this sublime we fell, myself and a number of my ‘Muni the teacher’ school friends, to the ownership of a “distinguished Gemara Melamed” from Budzanów. Without a doubt, he was a modest, G–d fearing Jew and a Torah scholar. But even a great scholar – May he forgive me up there in heaven! – was not a helpful teacher. Besides his moral lectures I can't remember any of his teachings. The Heder was located in the big Beit Ha'Midrash, and the studies were in the Beitzah Tractate. The Melamed from Budzanów (May G–d forgive me! I can't even remember his name) was a strange creature, and a number of tales that the world was telling about lazy Melamedim, were told about him. I will repeat and tell here one of them the way it remained in my memory:

Once upon a time, during the intermediate days of Passover, the Budzanówni Melamed from the town of Budzanów, left on the road leading to the village of Verbuvitch [Verbovczy] to converse the words of the Torah with R' Yisrael Glick. On the way he got tired (one of his legs was shorter than the other and he limped a lot). So he sat on the edge of a field to rest a little. Suddenly he felt sleepy and said to himself: the day is still long, I will nap a little and continue on my way. He took off his shoe with a sole that was the way of all other soles, and took off his other shoe with a sole that was eight times thicker since this leg was shorter. He stood the two shoes one after the other, the way they walk and said in his heart: when I will wake up from my sleep the shoes will show me the way and tell me to what side I need to turn in order to continue on the road leading to Verbuvitch. A prankster passed by, saw the two shoes and the order in which they were standing, and figured out the intentions of the Budzanówni. What did he do? He took the two shoes and changed their direction, standing them in the direction of Budzanów. When the Budzanówni woke up, he immediately looked at his shoes and knew in what direction he needed to walk. He put his shoes on and left. An hour later he returned to Budzanów. What “A great wonder,” he said to himself, “this Verbuvitch became larger! Verbuvitch is a small village but her buildings are the buildings of a real city.”. Very quickly his amazement grew bigger. “This street,” he said to himself, “looks exactly like my street in Budzanów, and this house looks exactly like my house.” He stood before his window and looked inside and saw his wife sitting by the table, a holiday scarf on her head and wire glasses on her nose, and she was reading what she was reading, since on a holiday she was not able to patch or knit, but he was still afraid to enter his home in case the woman was not his wife, only looked like his wife, or, G–d forbid!, it was the work of a witchcraft. He gathered his courage and shouted through the open window “show me the Ketubah!” Only after he saw the Ketubah that was written and signed legally – he calmed down and returned to his home and to his wife.

It became colder after the holidays and, by Hanukah, the river and the area around it were completely frozen. The brave students came out of all the Heders to slide on the ice and only I and my friends, the Budzanówni students, were missing from there. How is it possible? We started to sneak out from the dry and weary studies of the “distinguished Gemara Melamed,” who was not able to revive the matters that he taught us and make them interesting. He also started to lecture us about our morals, and the mouth that was stuttering and swallowing his words during an explanation, was the same mouth that emphasized his preaching in a pleasant and slow voice. He stabbed them in our flesh with the same pleasure that a cobbler pulls out small nails between his lips and nails them into the sole with direct blows. The regular version of the reproof was like a repeated song: If you don't want to study the Torah, what will become of you? You will not able to be a woodcutter or a water drawer, because you are not strong enough for that, you can't be a rabbi or a judge, a butcher or a Melamed – because you don't want to study the Torah. The only thing that is left for you is to be a tailor or a cobbler – is that proper and fit for your father, whatever his name is, for his son to be a cobbler or a tailor?”

When my turn came to hear this song of reproof, which was said in a pleasant voice and the great pleasure of someone who invented a convincing argument for the purpose of studying the Gemara, I already had a convincing answer ready in my mouth.

Rabbi – I answered politely – Is there a reason why all the Jewish children should be rabbis and judges, slaughterers or Melamedim? Surely, also cobblers are needed in the world! Never mind me, I buy ready made shoes from the factory, but rabbi, you can't live without a cobbler! Without cobblers in the world, who will make you a shoe with a sole that is eight times thicker than the other?

I was sure that the rabbi would be strict with me for mentioning his deformity, but I was wrong. He smiled with pleasure and said: “Shemsheli,' you are a wise lad, but you don't want to study. If you wanted to study, you would study and you would be able to reach the real knowledge.” And he did not know that I actually wanted to study, but his teaching was dim, unclear and boring, and it did not enter the heart and not even the ear.

Once he came to Beit Ha'Midrash and his entire head, side locks and beard, his eyebrows and mustache, were covered with fine feathers, exactly like the snow that fall outside in the morning. The only thing that was protruding from the sea of hair and feathers was his round flat nose. Probably, in the same night, the pillow under his head came undone. Shemsheli', his said to me in a laughing voice (G–d knows why he always had the happy face of someone who enjoyed life)” bring me a small mirror from your home. You know that, according to the Jewish code of laws, a Jewish man is not allowed to look at himself in a small mirror, but when there are feathers in his hair, he is allowed to look in a small mirror,” and again, a smile of satisfaction. I brought him a small round mirror that its diameter was the diameter of an egg. The rabbi brought the small mirror to his eyes, to his nose, to his side locks, and for a long hour looked at the image that was reflected from the small mirror, and he was not satisfied. Probably he was amazed from the great wonder, that a man can see himself in a mirror, and maybe he was so pleased from his beauty. At the end he gave me the small mirror back and smiled a smile of great satisfaction for deceiving Shulchan Aruch, R. Yosef Karo, and the “Ramah" [Rabbi Moses Isserles] all together and enjoyed what was strictly forbidden for him to do ….

“You are a good lad,” he suddenly said to me, “When you reach the age of Bar Mitzvah I will tell you the secret of how to create a person. Not in the explicit way and not like the Golem that the Maharal of Prague [Moreinu ha–Rav Loew] created, but a real person.”

The rabbi probably wanted to buy my heart, but his words with the added spark in his eyes did not scare me for some reason, and my heart left him and never returned.

I came home and told my father: I don't want to study with the Budzanówni. Father said: next period you will study with another Melamed. I said to father: this is not what I meant. I want to transfer to another Melamed right now! Father wandered: in the middle of the period? And to whom do you want to transfer? I said: I want to return to Ahron Goldhaber! Father became difficult: and you left him two years ago! I answered father: I did not leave him. He left town and went to the army, now that he has returned and a few of my former friends study with him, I want to go back to him. Father answered: and to study one page of Gemara a week? I added to his answer: but to also study the Homesh with Rashi, Pasuk and writing!

Father, of blessed memory, agreed. I was the youngest child, was orphaned from my mother and he liked me a lot. It was a courageous thing for him to do. To take a “sharp minded child” (this name was given to me) from the hands of a “distinguished Gemara Melamed” (the name that was given to the Budzanówni), and bring him back to a Melamed who taught him two years before. And what will they say about it in the Chortkov Kloiz? and it is possible to assume that it will cause a great financial loss since the Budzanówni was hired by the parents for a full period with a promise of tuition and food. And without a doubt, my father stood by his obligation in addition to the tuition that he paid R' Ahron.

This time, the Heder of R' Ahron was in his new apartment. Twenty–six boys sat on both sides of the long table, a bench on this side and a bench on the other side, from the end of this wall to the end of the other wall. Only a narrow passageway was left at the end of the table. R' Aaron stood behind the outside bench, one of his legs was standing on the bench in between two boys and a book was placed on the knee of that leg. And he read to us from that book as though he was reading it for the first time and the words were illuminated and happy! In the morning R' Ahron read and explained with a good mind and good taste, and in the afternoon we studied “Yeshaya” – the way it was done two years ago! But how different it tasted now and how different it felt. Two years ago I was the youngest in the group, the youngest among the older boys, number twelve or thirteen in the order of students, and now I'm the third, the second, and if you want to say – the first!

What is the “order of students” Only those who were R' Ahron's students know this secret! I already told that R' Ahron stood behind the outside bench that faced into the room, his leg on the bench and the book on the knee of the same leg, and so he stood and read each Mishnah, or each verse in the Gemara, or a whole chapter from the book of Yeshaya, and when he finished he asked: “Who say first?” – And the explanation of “say” is: to repeat and say everything, word by word, one from the source and one – a combination of translation, explanation and interpretation, nothing was missing! If a volunteer was found – he is the “first in the order”, if a volunteer was not found – R' Ahron decided who will “say” first and who will “say” second, who will “say” third, and so on until the last one, all the twenty–six students, so each Mishnah, each verse, and each chapter were “said” twenty–six times. And by doing so, the students' order of importance was decided, and everything that was studied sunk well in the brain and was carved very deep in the heart and was never wiped off.

I don't remember the names of all the students, but I remember the first five: Dudel Shechner who lives in Costa Rica, his cousin Butzi Shechner whose fate I don't know, Moshe Wachstein–Ami, the nephew of Dr. Bernhard Wachstein, who is now older and a farmer in Beit–Shearim, and his next door neighbor in Beit–Shearim, Kalman–Mordechai Sternklar, who is my relative and my partner to the sad period of exile in Lwów. Each time I visit Beit–Shearim – we spin memories from R' Ahron's Heder, and I entertain Moshe Wachstein with a truthful imitation of half a verse from Yeshaya, the way he said it in the evening of the same summer day in the same Heder in the new apartment. He was a tall skinny boy, his voice was also high, thin and shirking, and in this voice, that was elevated and extended high above, he blazed the words, like the high pitch of a metal flute, and said them with a lot of emotion. And I will swe–e–e–e–p it with the be–s–o–o–o–m of destruction, said the Lord of host….

On Thursday, in the afternoon, we studied Humash with Rashi. Each one of us read a verse and when the last word was still between his lips – his friend who was sitting next to him started the next verse, and so the reading was going around in high speed along the table from here and from there, continuously and without a break, and Alas to the boy who did not pay attention, and did not follow the reading, and his friend who sat next him already read in his place.

On Friday, after all the Torah portion of that week was fixed in our hearts, R' Ahron taught us some writings (it is a wonder how all the first Melamedim neglected to teach us writing, except for Muni, who from time to time taught us a few lines in Yiddish and German in large Gothic letters). We were not able to buy note books in the market, but we made them from blank empty pages that we found between the “Ektim,” the documents from the Austrian courthouse and other government offices, which were cleared from the cupboards and were used mostly for paper bags in the stores. Many families, adults and children, were busy making them, but empty pages were kept for writing and the notebooks were made out of them. Those notebooks were not lined, and R' Ahron had a small ruler and a small pencil, and with them he lined row after row in such a speed that the eye was not able to catch what his hand was doing. And before we turned here or there – twenty–six notebooks were lined with straight lines, in equal distance from each other, as though they came from under the hand of a magician. R' Ahron wrote a line at the beginning of the page, a line for each one of us, and we copied this line twenty times until two lined pages were full. At times we wrote in the holy language, at times we wrote in Yiddish, and at times both of them together – and the two languages served as one, with love and peace, and we almost didn't feel that we had two different languages before us.

Until the end of that winter period and another summer period, I was rewarded with good explanations and the system of R' Ahron Goldhaber. For the next winter period most of his “older” students left. I was also forced to leave and return to a “distinguished Gemara Melamed” and this time I became the student of R' Feybush the slaughterer.

Many years ago, R' Feybush, the slaughterer, was probably a handsome wise student without a stain on his clothes since he was the Chortkov Hassidism slaughterer, and they were known to be strict with their clothes and their appearance. But in my days he was already an old man. The hair on his head and his beard was white or yellow and his mustache was yellow – from the tobacco and from the tobacconist.

In my time, R' Feybush did not slaughter animals, but people brought him chickens a number of times a day. And, while he was teaching seven or eight students around the square table in his only room, he used to say to the first maiden who came: “sit on the bench and wait until another poultry will arrive and I will reply to you,” What is the “poor” word here? – I wondered in my heart, here is going to his death a white roster, a duck or a goose, some of its red hot blood will be poured into the trough that was made for that purpose, and some on the snow next to the house (if we are talking about geese that are not plucked, only something was taken from under their wings and thrown on the snow outside). And our rabbi says “reply”!

When the rabbi finally goes to “reply,” we take a break and go outside. The home of R' Feybush was very close to the river and the frozen reed marsh and the days were glorious winter days!

Across from R' Feibush's home, on top of a hill, is the workshop of R' Yedel Stupp the carpenter. And there, the saw is sawing boards, cutting corners and joints at the end, and the sculpting tool is sinking deep into the soft white board, and the sawdust is flying in the air, and the resin on top of the boards emits a good aroma and mixed with the smell of the boiling carpenter glue and the smell of the snow outside… Despite the chill – the window is open, Yedel the carpenter and his apprentice are always happy, and they don't chase me away from the window. On the contrary! Yedel loves to talk and he is always in a good mood. Not only that he lets me look at his work and ask him different questions, but he himself starts the conversation and explains the secrets of his work and the “thought” in it! And when I continue and ask a new question on the basis of what he already explained to me, he praises my good understanding and concludes his impression on me: “instead of Torah there is wisdom there”

What Torah and what wisdom did I buy from R' Feybush the slaughterer? I swear that I don't remember! I don't even remember the name of the Masecha that we studied. From that whole winter with Feybush the slaughterer nothing remains with me apart from a good understanding in carpentry that I purchased from R' Yedel Stupp through observation and conversation, and apart from one small “picture” in my poem “Snow”:

A goose that was slaughtered untied his legs

freed himself from his slaughterer and escaped;

He ran without making a sound or waving a wing

and his blood spilled on the snow.And so ran the goose with the slaughtered neck

to the white faraway world… –

and from the long slaughtered neck

coral after coral are rolling

In that winter, comfort and salvation came to me from another source. There was a second slaughterer in our town, R' Shlomo Schechter. Before the war, when there was still a fierce opposition between the Chortkov Hassidim and the Vizhnitzer Hassidim, he was the slaughterer of the Vizhnitzer Hassidim. But during the days of peace, a separation of that sort was unknown. R' Shlomo had three sons: Mendel, Yosel and Zalman. I always remember Mendel walking in the street with a book tucked under his arm (Herzl diaries or Zshtlovski's writings) and he was walking and arguing with friends about the current matters of the world: The Balfour declaration, the mandate on Eretz–Yisrael that was given to mighty England, and opposed to both of them – what is the value of Territorialism?! It is possible that thanks to the never ending arguments in the matters of Zionism, he immigrated to Israel on time, did not reject hard work, and now he and his family live in Tel–Aviv, a nice established family. A couple of years later, the middle brother Yosef, became my best friend even though he was a number of years older then me. Both of us remember with love those summer days when we laid on a large pile of good smelling hay, “swallowing” many chapters from the first book of prophets – to complete what I lacked from my studies with R' Ahron who skipped me from Yehoshua to Yeshaya. Also my friend Yosef saved his soul from the holocaust and arrived to Israel. From him I learned the details and the dates for my poem “The Minyan in my town, the town of Tluste.” He and his wife live in Kiryat–Shalom. The youngest son, Zalman of blessed memory, was my age and for a time my friend in the “Heder.” He was a good smart lad, but he was not a quick learner and his soul did not want to study the Torah. R' Shlomo was sorry about that, and wanted to teach him more than he studied in the Heder. In order to add desire to his studies – he searched and found a friend for him, and I was that friend, and that's how I became the student of R' Shlomo the slaughterer, not in order to pay tuition but to serve as a companion to his son. And so, I became a member of R' Shlomo's family and a friend to his middle son, Yosef, the pleasant and nice.

And how different was R' Shlomo the slaughterer, who taught me in the afternoon, than R' Feybush where I studied before noon! R' Shlomo was always dressed clean, and his beard, in which the first silver strings started to intertwine, was always well kept. When he checked the ritual slaughterer's knife, running it over his special fingernail, I realized how good looking his hands were, how delicate his fingers were and how beautiful his other fingernails were! He always spoke with kindness, he never raised his voice, even during class, and his explanations were done with good taste and kindness.

Also R' Shlomo stopped his teaching and left the room to butcher a chicken in a special chamber across the hallway near his apartment, but he always returned clean without a stain or a spot. His butcher knives frightened me, mostly the big ones. All of them were placed in their special cases, in a special corner between the wall and the oven. G–d almighty! How many times I saw this tender and gentle Jew, who did not even hurt a fly on the wall, swinging a big butcher knife and with a quick move, slaughter a big cow!

R' Shlomo was a lot younger than R' Feybush and slaughtered all the animals. Once, after the termination of the Sabbath during the intermediate days of Passover, I followed R' Shlomo together with my school friend Zalman to the municipal slaughter house across the bridge on the road leading to Chortkov. A large cow was lying on the floor with its back and front legs tied together and two young men were holding its large horns. R' Shlomo took out his large slaughterer knife, looked at it for a moment, lowered himself to the cow and grabbed the skin on her neck with his left hand. When I was ready to watch him bringing the big knife down – a large cut opened in the cow's neck and its hot blood spilled from the stone floor to the drain. My eyes darkened, my head was spinning and I was ready to fall. With weak knees I walked back home and for many years, after that year, I did not taste the taste of meat…… I did not even go to the home of R' Shlomo, mostly out of fear of his many slaughterer knives. The small ones and the big ones, between the wall and the oven ––––

And this is the place to mention another Melamed whom I studied with as an only student. Although I am not sure of the order of time, I remember that I studied with him during the summer period. And I'm not sure if it was the summer that followed the winter that I studied with the slaughterers R' Shlomo and R' Feybush.

This Melamed was the preacher R' Pinchas Lapiner who was not a native of our town. He came from a distant place, maybe from Lita, and for some reasons chose to live in our town Tluste. According to my opinion in those days, he deserved to serve as a preacher in a larger community or, at least, travel around the communities in the preachers' tradition. But, he sat permanently in our town and preached only two or three times a year. He preached: on Shabbat Hagadol [the Shabbat before Passover] (as we know our Rabbi, R' Shmuel Chodorov of blessed memory, was not a great preacher), during Shabbat Teshuva [the Shabbat before Yom Kippur] and maybe two or three times more during the year. On those Shabbat eves, hand written notices were posted in all the synagogues and in Beit–Ha'Midrash. They were the size of half a note book page and glued with a little glue. They announced: G–d willing, on the Sabbath, at three o'clock, the preacher Pinchas Lapiner will preach in Beit–Ha'Midrash and the listeners will be delighted. And indeed, the listeners were delighted. The preacher Pinchas Lapiner was knowledgeable in Nevi'im and Ketuvim, and Misrash Aggadah, and as a great expert he was able to thread twenty or thirty verses with one common word, to question from this verse to this verse, from that verse to that verse, all in one big pile of questions. And all the verses connected to each other and strung together like a string of pearls. He ended with: “And a redeemer will come to Zion”, kissed the Parocheth [the curtain of the Holy Ark], removed his Talith and folded it like an artist who created a beautiful work. When he was done organizing his equipment, he descended from the steps in front of the Holy Ark. And once again, he was “idle” for the next six months, until the next sermon. Only G–d knows from where he was earning his living and supporting his little modest wife and their lovely and sweet daughter, whose beauty, even the great poverty was not able to cover.

I was given to this R' Pinchas to study two hours a day and I went to him willingly and happy. Supposedly, he was teaching me the Gemara, but we skipped the difficult negotiation and passed from Aggadta to Aggadta [legend]. We both felt that we were cheating, but what could we have done? Everything depends on the heart, both of us were attracted to the words of the legends, and not only that we skipped from page to page and from chapter to chapter, we did not stay in one tractate [of the Talmud]. From Sanhedrin we moved to Gittin, but Heaven forbid! not to the matter of bringing a divorce from a country across the ocean. From page 55 column 2 to the bottom of column 1 on page 58, we read all the legends about the destruction that rumbled the heart – the days were probably close to Tisha B'Av – from Kamtza and Bar–Kamtza to the story of a man who fancied his rabbi's wife, an act that cannot be removed from the heart and will never leave it! And from there we skipped to the chapter that dealt with the hiring of workers in Baba Metzia, because there are also a lot of legends there. At the end we painlessly passed – Woe to the shame! – to read Ain Yakov exactly the way “simple Jews” read it in Beit Ha'Midrash or in the tradesmen's synagogue. “There is nothing bad in it,” R' Pinchas consulting me, “they are also the legends of the Torah, and if they don't sharpen the brain they warm the heart.” And R' Pinchas was rubbing palm to palm, as though it was winter outside and he needed to warm them.

All that I told here about this rabbi, I told out of love and appreciation. He was one of the few Melamedim whose teachings still live in me. He was modest and humble in his life, walked in the shade and on side roads. And when he walked on a side road, a German soldier shot him in the neck and killed him on the spot. I built a stanza for him in my poem “The Minyan in my town,” let us copy it here:

R' Pinchas Lapiner, the preacher of the holy community of Tluste, taught me the Gemara in a hurry –

May his memory be blessed; Woe how much I loved him and how he captured my heart!

He skipped the negotiations, jumped from page to page,

and taught me joyful legends – and I loved his skipping.

The death of R' Pinchas Lapiner is told in the poem mentioned above. When and how did his gentle wife and beautiful daughter die? – The one who knows his nation's troubles is the one who knows!

I told about nine Melamedim with whom I studied, but in reality there are ten stories, since I studied twice with R' Ahron Goldhaber and told about him twice. And between the ten I swallowed the stories of two Melamedim with whom I did not, but I knew them and their Heder very well. I did not want to skip them just because I was not one of their students. If I did not study with them, many children in our town studied with them, and it is possible that many of them are still alive and live around the world, including in Israel.

According to the review of our Tluste, I must add and tell here about two more teachers that I studied with as an only student. Not as a boy, but as a lad of fifteen and sixteen, out or my own free will, conviction and desire. But according to the age and time, they do not belong to the chapter of my childhood teachers.

One of the two was R' Yisrael Glick of blessed memory, our “relative by marriage.” The father of my brother–in–law, Dov Glick May he live long and happily, who sold his home and all of his belongings in the village of Verbovitch [Verbovczy] in order to emigrate to Israel. But on his way to emigrate he settled in our town of Tluste, to “wait a little” for his son, my brother–in–law, who was also planning to emigrate to Israel and take me, the teenager, with him. In the period of one summer and one winter I came to the home of my in–law, R' Yisrael Glick, who lived out of town near the “Hikand Mountain” and studied two or three hours with him. In the summer we studied in the shade of a rose bush that grew in the garden next to the house. And in winter we studied in the only room of the small apartment. And the father of my brother–in–law was sick and lay in bed, and I read for him in a sad quite tune.

The father of my brother–in–law, R' Yisrael Glick, recovered from his illness and, when spring arrived, his nobility arrived because the study of the “daily page” was introduced and he became the teacher and rabbi of the whole town:

My in–law Serueli' Glick, hurries each morning to the Chortkov Kloiz,

every day he reads a page from the tractate with humility and a modest soft voice,

and a father, a son, and a grandson are sitting around him listening to his voice.A Torah that was placed in a corner is dozing off,

and it seems that it will be forgotten soon, and it seems that it will disappear soon.

Suddenly it started to wake up, breathing with great force.He opened the gate to the Torah and led his students step by step;

He straightened each curve in the road and untied each tangle and complication,

everything without a sound and uproar, only with satisfaction and carful consideration.

But he was not rewarded to emigrate to Israel. The way his beautiful teachings entered the heart of his listeners below, they probably entered the hearts of his listeners above, and for that reason he was probably called to the next world. His many students in the Chortkov Kloiz were orphaned and I mourned him alone, the only student that he taught at home.

And the second teacher was the Hebrew teacher Mr. Mordechai Spector, who also came to our town from afar, and established a private Hebrew school. I, the “private” student, studied: Nevi'im, Ketuvim, grammar and “writing” – to write and to correct, to copy and again to correct and copy, Jewish history and world events, and everything that was available at that time in the Hebrew study books. At first I studied with him in secret and paid my tuition from the money that I earned drawing signs for the shops (most of the signs in town were my handy work) and in 1933, before I emigrated to Israel, the big sign that was placed in front of the home R' Hershil Meir, with a branched–antlered deer in the middle [Hersh – deer]. Later on, when winter came and the sign work stopped (the paint didn't dry, and in any case, the signs outside were covered with snow!) and I did not have the money to pay – I told my “secret” to my father of blessed memory. Out of the goodness of his heart he agreed to pay for my tuition in the name of “to give for a good cause”… since the Hebrew teacher was considered to be a secular man, and who–knows–what–he–was–teaching– there (and indeed we sat and studied the holy scriptures with an uncovered head, spitefully, as though with a covered head our studies were not “modern and scientific” enough).

I studied with the two teachers at the same time, the same summer and the same winter. I clearly saw the difference between them and the contradiction between them. This one was not like that one. This one wanted me to loath all the old, to open my eyes and see the ugliness in it, to awaken in me the desire for the new. And that one wanted me to love all the best and beautiful in the old, to open my eyes so I could see all the splendor in it, to explain to me that you can't build the new on the destruction of the old, only on the base of the old one.

And the equal side between them – both of them aimed their studies to the future, to the future of the young man who was ready to spread his wings and fly out of the nest. And both of them wanted to prepare him for the road: this one is teaching him all that he needs for the high school that he is longing to join, and that one is teaching him all that he needs in order to separate the essence from the subordinate, between the straw and the grain, and G–d forbids! that the young man will turn his back on it all.

The words that I wrote here are abstract, they only hint. But the words in my poem “In the shade of a rose bush” provide a better explanation and a better picture, and the man who said it in a song does not return and say it in an ordinary speech. Therefore, the one who wants to know this small and pleasant story, can kindly turn to that poem in my book “Scattered light”.

When my first small collection of my poems: “In seven strings” was published just before the break of the war, by the “Davar” publications, Tel–Aviv 5699, I was still able to send a few copies of the book to Tluste, one to my teacher Mordechai Spector and one to Rabbi R' Ahron Goldhaber. The teacher Spector probably did not have the time to answer me, if he did, I would have remembered it and his letter would have been kept with me. The Melamed, Rabbi R' Ahron Goldhaber answered me immediately, I still have his letter written in his golden language and this is what it says:

| “With G–d's Blessings: a day that was blessed twice in the order of days (5699).

May the mountains bring peace and blessing to you my student author, our teacher and rabbi Shimshon May his light shine. Thank you very much for the gift that you sent me from the fruit of the land, decorated with seven beloved strings like a sapphire and a diamond. And thank you that you remembered and the minister of forgetfulness did not rule you. I read from your book and I wondered how you turned in such a short time into a hero and became so successful, because this book can really raise the soul. My beloved, these poems are very lofty and I see a happy future for you, since a man with a spirit will rise higher. I wish you a lot of success in the land of our patriarchs and may your name be known around the world. My beloved! Despite the fact that I learned very little from this book and I lack the knowledge, I do feel the importance of your book. I bless you with the same blessing of the tree. May it be the wish that your offspring will be like you. Don't make fun at the style of my letter which is written in the language of a stutterer, because you know that I belong to the old generation and you can't bring the old from the new. Surely you will add to your first book and I ask you to send me a book each time. And with that I finish my letter, live in peace, a quite and fresh life, bless your family and friends in my name. Your friend, Ahron Goldhaber.” I was not able to fulfill R' Ahron's request and send him additional books. A year later, in 5700 [1940], when my poem “Meir the musician became a commissar” was published in a small book, “Tluste my tiny little town,” I was already cut off, far and distant, as though I was on a different moon, as though it never existed and was only a fable and a fantasy.

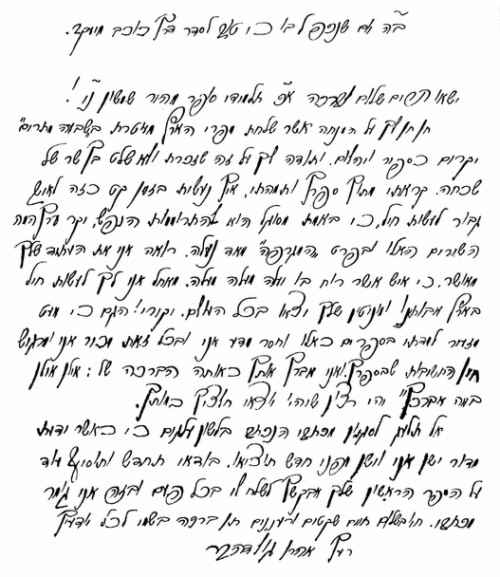

Now I am giving the letter that R' Ahron Goldhaber of blessed memory wrote me to the hands of the editor of this book. I ask him to create a plate and publish it the way it is – to be in front of the readers of this book. Probably a few of them, the students of R' Ahron, will recognize their Rabbi's handwriting. This is the handwriting in which he wrote the upper row in their lined notebook, this is the handwriting from which they learn to write in Yiddish and Hebrew – and if they look in their own letters, maybe they will recognize the Rabbi's letters in them. The intermediate days of the holiday of Succoth, 5676 [September 1915] |

| |

by Shlomo Mesing

Michael, son of Menachem (Mendel) and Shoshanna (Sasia) Mesing, was born in Tluste in 1908. In his childhood he received a traditional education. He was among the first to join the youth movement “Gordonia” and was also the organizer of the branch of “Gordonia” in our town. He was also one of the active members of “Keren Kayemet leYisrael” in Tluste, and among the organizers of the first “Halutzim” training program in our area.

In 1929, immediately after the riots of 5689 (1929), he immigrated to Israel together with the first company of “Gordonia.” The group's first stop in Israel was Hadera. After a stay of one year in Hadera, the Jewish Agency for Israel approached the group with an offer to move to Hulda and rebuild its ruins. Michael was one of the first volunteers to move to Hulda. They faced many difficulties, mostly the lack of water, but despite the many difficulties they didn't lose their spirit and continued their work to restore the place with vigor and stubbornness. Cheerful and full of joy of life, they approached the digging of the first well in the place, hoping that their work would be successful. But their hope was dashed and all their hard labor came to nothing. The drill hit a rock and the diggers' happiness ended. However, also after this great disappointment, the members of the Kvutza [communal settlement] didn't abandon the soil of Hulda and continued to cultivate it with all their strength.

There was no end to Michael's happiness when he was finally rewarded, after great efforts, to bring his parents to Israel and to Hulda. But his happiness didn't last long. In 1935, in the month of Sivan 5695, a typhus epidemic broke out in Hulda. Many members fell ill, and three of them, among them Michael, perished in the epidemic.

Michael was one of the best Halutzim who gave their lives for the building of the country.

May his soul be bound in the bond of life of the renewed nation!

From members words about Michael

Pinchas Lubianko (Lavon): “The terrible death plucked three victims”– said the news item. Your mute faces chase me nonstop. I see you day and night, and the question, which cannot be answered, erupts nonstop: For what, and why? I see you as healthy young men, I see Michael, our Michale”, the serious and devoted, in heart and soul, to the Kvutza. For ten years he lived the life of the movement and was one of its first builders. He carried the load of the Kvutza almost from the beginning of its establishment, suffered from unemployment, hunger and malaria in Hadera and was among the first who went to Hulda to lay the foundations for its development. Only a few months ago he brought his parents to the Kvutza. The father was surprised to see the order of life in the Kvutza, and there was no limit to his amazement when he saw his son, the “farmer,” and he himself held to any work in order to “earn” his bread. Also the mother participated in the young womens' work and was influenced by the new way of life. She believed that together with her son, Michael, she would be able to build a peaceful and secure future for herself.

…and what can I say to you, my beloved, in far and near Hulda? Can we also overcome this blow? That faith must win over despair? That life, creation and war demand victims? Our entire “Gordonia” family united with the Kvutza in Hulda with its pain and great tragedy.

You don't need these meaningless and banal words of comfort. You know very well that you are not alone and lonely. You feel deep inside the will of those who left, and the duty of life – for life.

My beloved brothers, honor to the memory of the dead, honor to your suffering and stubbornness.

(From the article “On the way” written in Polish and published in the movement's journal).

Zalman: When I arrived to the Kvutza I already found him there. I did not know him from abroad the way I did not know the rest of the members. But Michael stood out among everyone as a handsome young man with black hair, black shiny eyes, and a smile on his face. He mostly excelled in his will to help the new member, the “green,” whether with advice or whether with an act. Even though he came to Israel only a few weeks before me, he was like a veteran in everything. He was aware of everything that was happening in the Kvutza, actively participated in all of its affairs and also in the affairs of the entire movement. Also, the affairs in Hadera, and the community of workers within it, were not foreign to him.

When it was decided to leave for Hulda and rebuild its ruins, Michael was given the duty to guard the place. Michael did not know Arabic and not even the Arabs' customs and started to study Arabic in his characteristic diligence. He sat for hours next to the Arabs' well and listened to the conversations of those who came to draw water. By doing so, he learnt to speak like one of them and they respected and appreciated him for that. Despite the fact that he stood on guard, day and night, he did not neglect the matters of the Kvutza, and was one of its active members. Also, in the most difficult situation he knew how to defuse the tension with a proverb or by telling a joke – and the matter became easier on the heart.

It is impossible to describe his happiness when he was able to bring his parents to Israel, but the happiness did not last long. He also became ill with typhus during the epidemic in Hulda. He was taken to the hospital and never returned from there. Even today, twenty–five years after his death, his image is standing before my eyes.

May his memory be blessed!

(From a booklet in memory of the typhus epidemic victims in Hulda)

Frida Sidrer: I knew Michael Mesing z”l when we were members of the movement abroad, and even before I knew him – I've heard about him. I knew that Michael is a friend that you can count on because his dedication to the matters of the movement was ”well known.” If you're going to organize a “summer colony” in the district – you had to turn to Michael, and if a pioneer training group was in trouble and needed immediate help – he was the one to address. He was active in the movement as he was waiting to fulfill his aspiration – to immigrate to Israel.