|

|

|

[Pages 8-10]

by Dr. Dov Levin

Translated by Martin Jacobs

For many generations Lithuanian Jewry has been praised in the Jewish world for so many things, among them being as a center for Torah learning and for Haskala (the Jewish Enlightenment movement), as a workshop for movements and schools in the intellectual, ethical, and social spheres, as the stronghold of Hovevi-Tsion (an early organization for Jewish settlement in Palestine) and of Hebrew education, and as a source of pioneers for the Land of Israel.

This Jewish community began to display its uniqueness as early as the period of the union with Poland (“Council of the State of Lithuania”) and it was prominent in great measure in the days of Tsarist Russian rule (1895-1915)[1]. Indeed it is worth clearly pointing this out for the period of Lithuanian independence (1918-1940), from the day of its founding at the end of the First World War until its conversion into a Soviet republic at the beginning of the Second World War.

In the period between the two world wars about 160 thousand Jews lived in Lithuania, in about 250 communities, old and new. In almost every one of them, whether city or small town, prayer houses and community institutions were active, both religious and secular; schools (the majority Hebrew, a few Yiddish); branches of movements and parties, Zionist and others; hakhshara communities (which prepared youth for emigration to Palestine, mainly by teaching agriculture); and Ulpan houses (schools teaching Hebrew) which taught Torah in various classes, starting with the heder (elementary school), traditional or modern, and going up to smaller and greater yeshivas (religious academies).

Four communities succeeded in becoming Torah institutions which were much esteemed throughout Lithuania and perhaps in the entire Jewish world: Kelm (Kelmė), Slabodka, Telshe (Telshe, Telšiai), and Ponevezh (Panevėžys). As is well known, these institutions were named for their geographic locations: the Kelmė Yeshiva, the Slabodka Yeshiva, the Telšiai Yeshiva, the Panevėžys Yeshiva. Except for the last one, these yeshivot were established in the last third of the 19th Century. They were set up and their spiritual path was delineated at that time. Great sages of Israel were involved in this, at their head the intimate disciples of the founder of the Musar movement (a movement to further ethical and spiritual discipline), Rabbi Israel Lipkin of Salant (Salantai), the “Salanter Rabbi”. A unique method of study flourished and developed in these yeshivas, known as “the Lithuanian method”, based essentially on a deep and honest understanding, on precise analysis, and on sound reasoning.

These institutions reached the height of their spiritual development and their material success in the 1930's, which were also years in which Hebrew education and Zionist activity flourished and gained eminence. When, during Soviet rule (1940-1941), the system of Hebrew education was abolished and the strongholds of Zionism were liquidated, the Torah institutions were also severely affected as a result of prohibitions and limitations, or of a ban on building which reduced their existence to a minimum. The bitter end of the majority of Lithuanian Jewry, both religious and Zionist, came about as a result of the Nazi occupation at the end of June 1941. Among the communities which were slaughtered and destroyed by the Germans and their Lithuanian helpers in the summer and autumn of that year was the ancient community of Telshe, three hundred years old, which was said to be renowned far beyond the borders of Lithuania.

The extensive collection presented here and dedicated to the community of Telshe is being issued forty four years after the physical destruction of the community at the time of the great calamity which befell the majority of Jewish communities in Europe. Thus it is also a book of remembrance, a glorious monument to a glorious community which was the innermost heart of religious Jewry in Lithuania between the two world wars. If we can make a comparison, we could say that just as Jewish Lithuania is called the “Land of Israel in Exile” and Vilna the “Jerusalem of Lithuania”, we might just possibly call the Telshe community the “Yavne of Lithuania.”

And indeed the trend of religious education in Lithuania led to the proliferation in the city of what we have called Yavne of an appreciable number of the best institutions, among them the Yavne Gymnasium (Hebrew secondary school) for Girls, founded in 1921, which served as a model for the other mid-level institutions of this type throughout Lithuania. Furthermore, the Yavne Teachers Seminary (the only one of its class in all Jewish Lithuania), founded in Kovna (Kaunas) in 1923, moved to Telšiai after several years and graduated ten classes of students there, until it was closed by the Soviet authorities. These institutions and others (most of which are mentioned in this book) started with kindergarten and went up to the Kollel Avrakhim (Community of Married Scholars), thereby constituting an appreciable part of the great Torah system which developed around the Yeshiva in Telshe.

The majority of these institutions, including the yeshiva itself, were identified in the 30's both ideologically and politically with Agudath Israel, whose influence in the city kept on growing. The two central organs of the Aguda in Lithuania, HaNe'eman and Der Idisher Lebn, also appeared here.

The ideological and cultural activity of the secular community also continued in orderly fashion, in its various parties and organizations, most of which are mentioned in the book. Between the extreme Orthodox community and the secular community (and even the moderately religious) there were often struggles over ethical and ideological matters and even over positions of power. The reader will find here extensive material about such phenomena, current in Telshe from the period of the Haskala (Jewish Enlightenment Movement) on, including the incidents and polemics in which the well known poet Yehuda Leib Gordon was involved.

For the convenience of the reader and for the sake of orderliness the book is divided into five sections. The largest and most comprehensive of these is called “The Telshe Yeshiva – its Rabbis and its Institutions”. And indeed the major part of the section is devoted to these topics, which are brought back again with various points of view in additional sections, such as “The History of Jewish Telshe”, “Personalities”, “Memories”. These three sections present very important details about the life of the Jewish community in Telshe, and a description of the events of the old families of the area and of the personalities central to the establishment of the Yeshiva and to its leadership, up to its last day, dealing either with the founding fathers and Torah greats, like Rabbi Nathan Tzvi Finkel (the “Grandfather”), Rabbi Solomon Zalman Abel, and Rabbi Simon Judah Shkop, or with the rabbis and heads of yeshivas from the school of Rabbi Eliezer Gordon, Rabbi Joseph Judah Leib Bloch, and Rabbi Chaim Rabinovitz. These great scholars were also founders of prominent and important dynasties which left their mark on congregational life. Unfortunately these dynasties were cut off in their prime, after a generation or two, because of the terrible calamity which came upon Telshe along with all the Jewish communities during the Second World War. As a result the shadow of the Shoah (Holocaust) hovers over many parts of this book and the reader will feel this without any doubt.

The essential details and the descriptions of the bitter and sudden end of the Telshe community are presented in concentrated and systematic form within the section “The Holocaust”, which is the second largest section in this book. When we read the shocking facts of the last days of the Jews of Telshe we see the same known conclusion repeatedly verified concerning the enthusiastic participation of the local Lithuanians in the implementation of the murderous deeds and the oppression and humiliation of their neighbors, the Jews. From the description of the facts it emerges that the process of destruction of the communities was a short one, relatively, and the ghetto in which mainly women and children were confined had already been liquidated by the end of 1941. Perhaps this is the reason the Jews of Telshe did not succeed in organizing any resistance movement at all. Nevertheless their courageous conduct and the pride of several individuals, such as Isaac Bloch, a leader of Betar (a Revisionist Zionist youth movement), will serve as a lofty expression of symbolic resistance when faced with death. Furthermore, it seems that a number of Telshe Jews succeeded in actively joining the fight against the Germans.

Facts such as these, and others too, some of which are published here for the first time, are presented in abundance in this book. Because of this the book is intended to serve as an important source for everyone interested in knowing about and exploring the Jewry of our time in Eastern Europe in general and Lithuania in particular.

As everyone agrees, the committee of Telshe émigrés in Israel, and editor Yitzchak Alperovitz, who took the trouble to locate the material, edit it in a balanced manner, and beautifully publish it, deserve a hearty “Congratulations and thank you”.

| Dr. Dov Levin |

Coordinator's footnote

The Editorial Board of the Telshe Memorial Book

Translated by Paul Bessemer

With the publication of the Telshe (Telšiai) book of remembrances, we are kindling a Ner–Neshama [“light of the soul”][1] for our loved ones who were martyred in the calamitous tempest that came upon the House of Israel during terrible period of the Shoah. Within this book of remembrances is wound a “scroll” of Telshe [telling] about its illustrious past and its bitter end. We, the surviving remnants of the community of Telshe, have taken upon ourselves the special mission of establishing a Yad VaShem [“a memorial and a name”][2] for our community so that its memory shall endure forever.

Over the decades since our community was destroyed in the deluge of blood and conflagration ignited by the Nazi Asmodeus,[3] these Holocaust survivors and those who left the city in the years before have carried with them the dream of immortalizing the memory of their loved ones who were brutally killed in mass graves in Rainiai and in Geruliai,[4] so that it be preserved as a witness and testimony, that if there are others like us, survivors of the community of Telshe who are dispersed to all corners of the Earth, they may immortalize the memory of our ancestors and the vibrant life of Jewish Telshe. Like leaves blown in a swirling wind, we remain few in number, charred pieces of wood saved from the conflagration, and, with our remaining strength, we have begun to spin the thread that connects us with our plundered community that has been wiped off the face of the earth and is no more.

Since the end of the Second World War a moral and national debt has lain upon us to preserve for eternity the memory of our community. Among those Israeli immigrants from Telshe there are a few for whom the publication of a memorial book for Telshe has nagged at them for years. They were a handful of persons who were hopeful and greatly desirous [of putting together such] and believed in the possibilities hidden among and inside us, and who never tired of raising the subject again and again until the dream was finally brought to realization.

It was in the month of Kislev 1971,[5] that we, a small group of immigrants from Telshe, gathered together in Tel Aviv at the “King Solomon” school, which was under the direction of our fellow Telshe resident, Dr. Malka Israeli–Blechman, and there we laid the foundations for the “Israeli Immigrants from Telshe” organization. Since then, we have held memorial services for the martyrs of our city every year on the 20th of the month of Tammuz – the day that the community of Telshe was annihilated.[6] The main speaker on these annual memorial days was Dr. Holtzberg–Etzion, [who had been] the director of the Yavne gymnasium in Telshe.

[Page 11]

In order to expand our activities, the executors of the organization, Dr. Malka Israeli and Tuvia Ba'al–Shem, turned to Shoshana Holtzberg–Yafeh from Jerusalem and to Shmuel Natanovitz of Tel–Aviv to join our executive committee, and both responded [positively] to our request. The first objective was to place a memorial plaque/stone among those for other communities of Lithuania that were destroyed during the period of the Shoah in the “Chamber of the Holocaust” on the Hill of Memory[7] in Jerusalem, and thereby immortalize the memory of our illustrious community. And the plaque was indeed placed there after considerable effort.

With the appearance of memorial books for the Lithuanian communities that were destroyed during the Second World War, a deep sense of sacred obligation was felt by those from Telshe to immortalize the memory of some 3,000 victims of our anguished city through a [similar] memorial book. But later on, as the number of former inhabitants of Telshe in Israel was small, the mission appeared near impossible [to complete] and the idea of immortalizing our community faded more with each passing year. It was only with the increased flow of immigration from Lithuania during the 1970s[8] that favorable conditions were created to bring the idea into reality.

At the meeting of the members of the organization established in 1976 in Tel Aviv it was decided to submit for publication the memorial book for the martyrs of our city in recognition that this was the last chance to rescue and preserve the testimonies of the Shoah survivors of Telshe who miraculously survived the killing fields and other survivors who immigrated to Israel and to gather important material for our memorial book.

For this purpose an editorial board was chosen that concerned itself with collecting rich and varied material that would enrich the book. Among its members were appointed: Dr. Malka Israeli–Blechman; Tuvia Ba'al–Shem (serving as head of the organization); Shmuel Natanovitz; Tzvi Brik;[9] Mina Girsh–Bod; Yocheved Varias–Holler; and Shoshana Holtzberg–Yafeh from Jerusalem.

Before us lay two objectives:

Over the long period of preparing the book for print, we worked to the best of our ability to add all the material possible: lists, photographs, documentary material, and, in particular, we wrote up lists and recorded memories just as they had been preserved by those who wrote them down. Also included in the book were essays and descriptions of well–known public persons who lived and studied at the Telshe Yeshiva during various periods.

Our thanks go out to all the [former] sons and daughters of our city for their generous assistance in publishing the book. We also express our gratitude to Rivka Naveh–Katz, a student at Yavneh who helped to make the idea of publishing the book a reality. And finally, we send our thanks to the book's editor, Mr. Yitzchak Alperovitz, whose expertise and [sense of] responsibility contributed to the book's pleasing design.

[Page 12]

We thank all those who assisted in this production of ours, whether materially or spiritually, and who thereby enabled the memory of this holy Telshe community of ours to be preserved for eternity. May you all be blessed.

This book shall serve as a monument of memory and its pages shall be a place of contemplation for the benefit of our fellow landsmen who are scattered to all corners of the earth.[10] In the hope and prayer that the image of their pure lives and the sanctification of Israel that they possessed at the time of their destruction shall be permanently inscribed in our memories and in the memories of the coming generations.

May their memory be a blessing!

Translator's footnotes:

by Yitzchak Alperovitz

Translated by Paul Bessemer

To the series of memorial books for the Jewish communities that were annihilated at the hands of the Nazis during the Shoah is now added the Telshe memorial book. The community of Telshe served as a symbol for the Jewish communities of Eastern Europe and was a precious flower within the bouquet of Jewish communities in Lithuania before the Shoah. It was an unpretentious group of Jews with a unique character, one bestowed with particular spiritual qualities (mehunan be's'gulot nafshiyot meyuhadot). These people were firmly rooted in the lands of Lithuania and dedicated to Jewish tradition and culture.

Telshe was the essence of Lithuanian Judaism. Its sense of community was a part of this Judaism; [despite the] factors that throughout its history made it subject to difficult administrative and political conditions, Telshe knew how to establish its economic, spiritual, religious, and public life. A network of public institutions was established within [the community] that attracted Torah scholars and thinkers. Much of its spiritual power lay hidden just below the rough surface of the Telshe community.

Telshe was Jewish not only because of its inhabitants, but in also in its rich diversity of stark contrasts: In Telshe the old encountered the new, the pious [encountered] the enlightened, the religious fanatic [encountered] the secular, [and] public servants [encountered] the “common folk.” There were, among the Jews of Telshe, great Torah scholars and Jews of wide knowledge and extensive education. In Telshe there were assembled great creative forces and a city in which both the spiritual and the material coexisted, and where numerous, diverse Jewish families intertwined in a wonderful, complementary manner.

Over the course of centuries, Telshe became known within the Jewish world thanks to the rabbis and ga'onim[1] who lived there. They served not only as spiritual leaders for Telshe itself, but also filled an enormous role in Jewish life throughout Lithuania. Echoes of the activities of the rabbis of Telshe and the heads of the yeshiva reached the Jews [in the rest of] Europe through the books that they composed and by virtue of the famous yeshiva that existed until the period of the Shoah under the leadership of the distinguished rabbis, Rabbi Eliezar Gordon, Rabbi Yosef–Leib Bloch, Rabbi Shim'on Shkop, Rabbi Chaim Rabinovitz, and others.

From the scattered knowledge of the community of Telshe [found] in both external and internal sources the unique lines of the community's character appear. The changes and transformations that began within this community over the generations reflect the same changes and transformations that transpired all over Lithuania and which were unique to it, both in communal and economic terms, as well as in cultural and social terms.

|

|

[Page 13]

A memorial book to the community of Telshe – this is the story of the life and destruction of an illustrious Lithuanian Jewish community that was in existence for many generations. In this book an attempt is made to extract general lines from within a large and expansive web, lines that will serve as an additional aspect to what has already been written in the articles, historical surveys that are scattered throughout a great number of manuscripts, and in books. Telshe was blessed, perhaps, with more material than other communities. The city itself would continue to represent a source of pride for its inhabitants. Its special character and social values over the years of the community's existence were expressed and found a place in the recollections of the city's residents. The abundance of [source] material in the book has no doubt contributed to the painting of a [more] complete portrait of this vibrant and vital community.

The span of time of the recollections in the book is, relatively speaking, great indeed: they begin at the end of the previous [19th] century [and go] until the community's extermination during the Shoah. The book does not pretend to reflect all aspects of the varied life of the Jews of Telshe, but is instead a portrait in miniature of the original reality. We would not purport to claim that we have succeeded in discovering every way of life in Telshe; they do not reach full expression here. Nevertheless, we have taken care that, to the greatest extent possible, the book would include and reflect Telshe Jewry on all its various levels, movements, and currents, from the very beginning of the community's constitution until its destruction. We also concerned ourselves that every list or survey would be certified and as reliable as possible. It should simply be added here that, despite all our varied and repeated appeals [to sources], we were unable to acquire suitable material on the number of important persons in the city and the various public institutions that held a prominent place in the lives of the Jews of Telshe. But what there is is of greater benefit than what is still lacking.

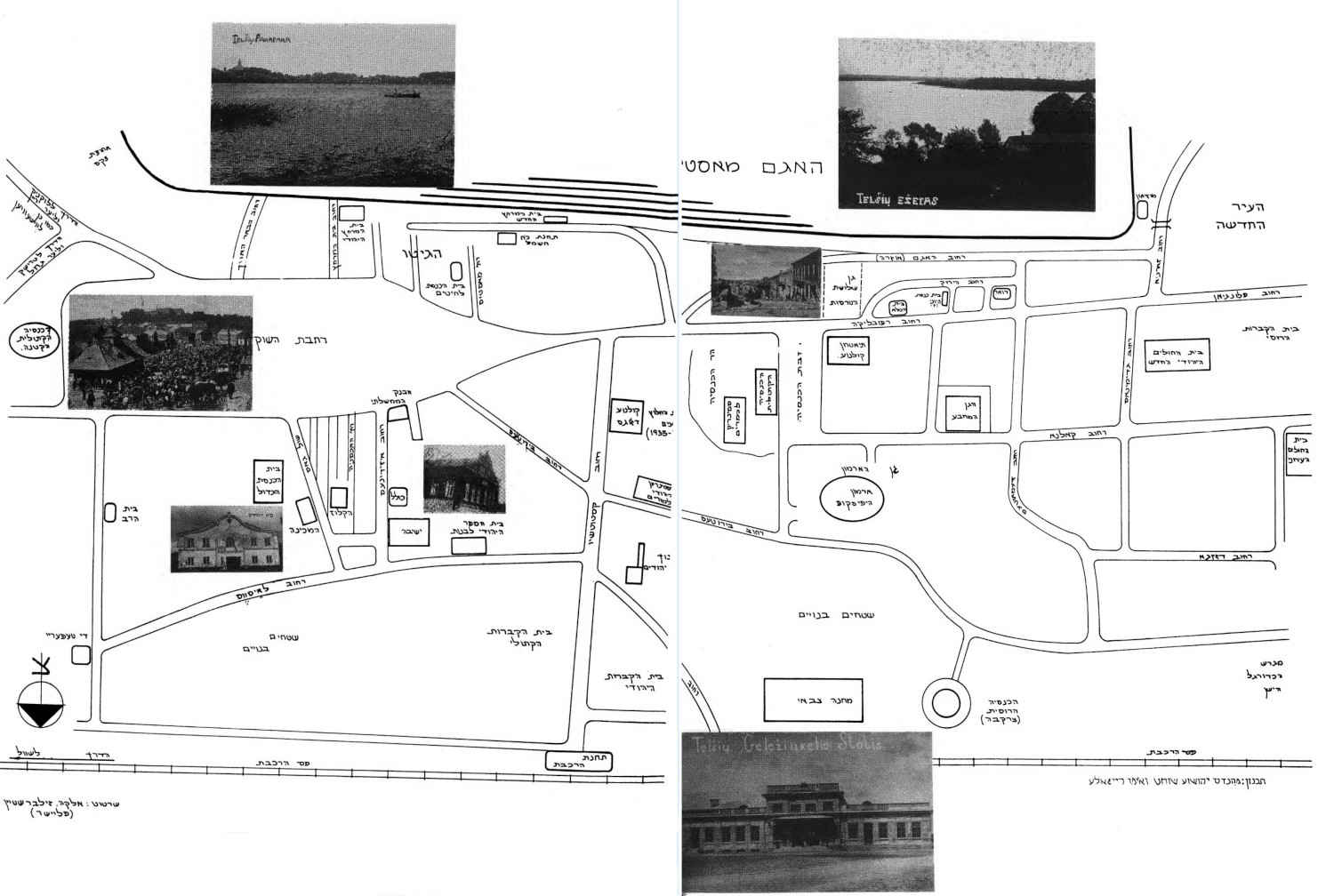

In the Telshe book a special place is devoted to articles and surveys of the certain periods and events in the life of the community. The survivors of the city wrote of their longing for their family homes and community that were destroyed. An important place in the book is also the chapters on the history of the city, on the yeshiva, on the persons and characters, on the network of religious education, and an important chapter on the Shoah. In this chapter are gathered the lists, recollections, testimonies, and diary excerpts from the Holocaust survivors. Among the pages of the book are scattered many photographs, especially landscapes of the city itself, of its public institutions, of rabbis and public figures, and of educational institutions and youth movements.

An important link in the book is the memorial pages and the list of martyred inhabitants. We know that the list is not complete, and that many names are missing and this, is despite the many efforts and appeals made by the editorial board to locate for us the names of their relatives who perished. To our great misfortune, these [efforts] did not bear fruit. We concerned ourselves to include within the book's pages the names of the descendants of Telshe who gave their lives in Israel's wars, defending the homeland, as well as the names of those sons of Telshe who fell on the various fronts during the Second World War.

I have the pleasant duty of mentioning the important assistance of the members of the editorial board who contributed so greatly to the book. They are: The Organization's Acting Head Tuvia Ba'al–Shem, who is the guiding spirit of the organization, and who has devoted his entire life to Jewish Telshe. A dear spirit, he is industrious and capable and has always labored unceasingly; he did not rest, instead mobilizing many people on behalf of the goal of publishing the book. It is he who bore the principal burden of doing the hard work, and of doing it with devotion and faithfulness, and he accompanied the work of preparing the book for publication from the very beginning until its final printing. He gathered much material for the book, wrote down and recorded lists and recollections orally recited by the survivors of Telshe, and then prepared them for print. He also devoted much labor to collecting the funds [needed] for the book's publication. Without his active assistance, this book would have never seen the light. He also contributed, through his own blessed handiwork and lists scattered within the pages of the book. Also included in the blessing is his wife Tova, who helped him from beginning to end with the difficult task of publishing the book.

[Page 14]

My gratitude is also given to Dr. Malka Israeli–Blechman, a member of the editorial board who was the initiator of the book project in the first place. She contributed her handiwork and participated in setting down the principal directions that the book would take and its publication. A special [note of] appreciation goes to editorial board member Tzvi Brik, who devoted a great deal of his time at every stage of preparing the book for print and also contributed his handiwork. He was a great help to Tuvia Ba'al–Shem in collecting funds and acted with dogged determination to realize his goal. Likewise, he accompanied the book project from the beginning of its preparation until its final publication and he bore, along with Tuvia Ba'al–Shem, the main burden of bringing the book to print. A special [note of] appreciation also goes to editorial board member Shmuel Natanovitz, who became enthused with the idea of publishing a book. He contributed of his own blessed handiwork and great talent to prepare a thorough survey on the history of the city and the yeshiva. My thanks go to editorial board member Yocheved Varias–Holler, who took on the burden of publishing the books. She contributed her handiwork and participated in the meetings of the editorial board. My thanks to Shoshana Holtzberg–Yafeh, a member of the editorial board who enriched the book with a great deal of interesting material. I must also mention the professional assistance of the printer, Mr. Moshe Hamiel, who assisted in the design of the book in every stage of his work.

A special thank you is due to Berl Cohen (New York), a native of Telshe, who edited a number of articles in Yiddish and prepared a fundamental survey on the history of the city, on the yeshiva, on the patterns of life in Telshe, on the rabbis of Telshe who for generations presided over the city, from the founding of the community until its end during the Shoah. He diligently worked through a great deal of material and prepared his survey on the basis of a rich bibliography and his scientific work bestows an illustrious dimension upon the book.

An expression of gratitude and a blessing are sent to all those who lent a hand in the publication of the book, both those in Israel and those who are abroad.

Translator's footnote:

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Telšiai, Lithuania

Telšiai, Lithuania

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 1 Mar 2022 by LA