[Page 357]

Memories

by Simcha the son of Yacov Langsam

And the Lord said onto Moses: “Write this for a memorial in the book and Rehearse it in the ears of Joshua…”

G–d had awarded two precious gifts to those he created when he blew into them the breath of life. What you do not like to remember you forget by force or forgetfulness and what you don't like to forget you remember by force of memory.

I have a special affection for the second gift because whenever I remember an event that occurred in my life, my desire to thank and to proclaim the greatness and the wonders of the Almighty increases. Therefore, it is my duty and my holy command to write the memories of the period when the world brought down the Holocaust upon our people from which I and a very few fortunate Polish Jews survived.

My brother Yechezkiel and I, together with hundreds of Jews, went on a journey to seek refuge from the claws of the Hitlerist bands in 1939. After many travails about which I told in a previous chapter, we arrived in the city of Lesko. This city is located on the other side of the San River which, at that time, was the natural border–line between the Polish territory occupied by the Soviets and the Polish territory occupied by the Germans.

By the lights of German search lights, we crossed the San River which was overflowing. It was a shocking sight. Under the cloak of the darkness of night, a group of Jewish people – the elderly, women and infants among them, were stranded in water which reached up to their chins. Their clothes and belongings were wet and the danger of drowning was imminent. It was the rainy season. “I am drowning. Please help me. I am a father of small children” pleaded an older man with his last breath. Indeed, with great effort, I successfully brought him ashore.

Excited, shocked and wet to the marrow of our bones, we found ourselves on the shore of the noisy river in Soviet territory. Some of the refugees who had already tasted the taste of death under the Germans were kissing the ground of the free land. Some recited the morning prayers. There was a strange feeling, a feeling of joy mixed with sadness. On one hand, although we could still see the Germans on the other side, we were out of their reach. On the other hand, our hearts were filled with a new worry: what was going to happen to our dear ones who remained in the hands of the murderers?

The border guards that carried light arms welcome us with a repeated request: “Quiet!” (We did not know then that silence in that land is the means of survival).

Heavily guarded, we were brought into a large movie hall in the city

[Page 358]

of Lesko. We were told that we were arrested for investigation into the purpose of our coming, whether it was espionage for the Germans. We encountered rabbi Kalonymus, the young rabbi of our town among the arrested. He was very depressed but he told us that something was being done on his behalf. To our joy, he was freed after a few days as the result of the intervention of a few Jewish communists who had recommended his release.

From Lesko, we were transferred by the N.K.V.D. authorities to the city of Lwow and imprisoned in the famous “Brigidki” prison. After a thorough search of all parts of our bodies, all “forbidden” articles were confiscated. We were dispersed throughout the prison in different cells – about seventy or eighty in a cell, cells which in normal times would hold twenty–five prisoners. The fact which depressed us the most and caused much pain to the imprisoned was the confiscation of the tefilin. The Jewish communists threw all the tefilin into a big pile in the prison yard. A shudder went through our bodies when we saw what was happening to something so sacred to us for generations. We felt that this horrible war was also a war against the Jewish soul. We realized that this denigration act was a special “treatment” against the Jews. We protested to those in charge but their reply was: “Our land is a free land. You can pray undisturbed but the prison is not a church!”

One of the prisoners did smuggle in a pair of tefilin and that news encouraged us. Most of the prisoners had forgotten what they had gone through lately and found consolation in these phylacteries.

It is hard to describe the first night in prison on a bank–bed made of boards. Despite the exhaustion of the last few days, nobody slept a wink. At daybreak and after fulfilling a few prison regulations, we all lined up for the donning of the tefilin. People who had never in their lives donned a tefilin lined up. Everybody recited the blessing and handed the tefilin to the next in line. We did it in a corner, out of sight of the jail guard. There were in our cell people from Frysztak, Jaslo, Krakow, Tarnow and Rzeszow, but none from Strzyzow. We later found out that the son of the assistant rabbi from Sendziszow was in one of the cells. I was told that he had refused to eat any food except for bread and water. He was very depressed and suffered from all kinds of aches and pains.

Once in a while, I succeeded in sending him a carrot or a piece of sugar which was given to me by a Jewish prisoner from Bukhara who worked in the kitchen. It was only by accident that I found out that he was Jewish. I saw him once moving his lips before his meal and so I asked him: “What are you mumbling?”: “I pray”, he replied. When I asked him to say the prayer louder, to my astonishment, I heard him recite the blessing “Netilat Yadayim”. That is all that is left in my memory from my father's house, blessed be his memory. “I am Jewish” he said in Russian because he did not speak Yiddish.

There were about two quorums of Jews in my cell. We tried to encourage each other and we sought consolation in all kinds of discourses in Torah and in the words of our sages.

During that period, I befriended a man from Rzeszow – Reb Samuel Nachum Emer – a peculiar type, about whom I will tell further on.

[Page 359]

After I spent three months in Lwow, I was transferred to the Ukrainian prison if Kiev, Charkov and others. With each transfer, I was separated from the people with whom I had found a common language. Especially painful was my separation from my brother Yechezkiel. He was sent to another prison and I did not know his whereabouts until the liberation.

In order to understand how much our looks had changed, I would like to tell here an interesting episode. In the cells, besides the Jews, there were also non–Jewish inmates – Polish anti–Semites and other extreme nationalists who hated the communists in Poland and preferred the Nazi. They waited for them for years before the outbreak of the war.

Suddenly the door opened and the guard ordered us to move over and make room for more inmates. A few people came in, frightened, with torn and shabby clothes, some Jewish and some not. All of them were searching with their eyes to spot an acquaintance, a relative or just an ordinary Jew. I too looked at the newcomers and noticed a Jewish face and soon began a conversation: “From where is a Jew? How long ago did you leave Poland? How is Jewish life in Poland?” and many other questions. After I finished questioning my neighbour, he heaved a deep sigh and began to reply to my questions. He suddenly burst out with a cry: “Simcha! Simcha! Don't you know me? I am Samuel”! I mobilized all my brain cells but could not recognize this bearded young man who looked my age and who, only a few months earlier, had prayed with me in the synagogue and had strolled down the streets together on a Sabbath afternoon. I could not believe the changes that had occurred in such a short time. When he saw that I could not recognize him he told me that his name was Samuel, son of Reb David Lieberman from Strzyzow. At present Samuel resides in Petach Tiqua, Israel. After being together for twenty–four hours, the separated us again.

Zitomir

by Simcha Langsam

On the outskirts of the town there was an isolated three–story building surrounded by a wall and watchtowers on each corner. This was a prison and in it the authorities assigned me together with thousands of other Jewish residents.

In the cell with me were a few young men who belonged to the Zionist Religious Youth Movement; the rest of the inmates were elderly observant Jews. In the first few days, we felt only depression and despair. We were cut off from the whole world without a newspaper, without any contact with our families and we did not know what was happening on the front lines. We worried about our families that had remained in the hands of the murderers. Hunger, filth and sleepless nights imprinted on us a horrible impression. Continuous nightly interrogations and the threats of the interrogators that tried to force confessions of spying from us, for which we could be sentenced to fifteen or twenty year's imprisonment, brought mental suffering upon us. All the above sufferings united us; the religious young men and the observant Jews into one large family in our daily prison life. All these shared factors were the source of our unity.

[Page 360]

The most uniting force in our group was Reb Samuel Nachum Emer, of blessed memory. This man encouraged us and instilled in us a belief and confidence in the eternity of Israel. He strengthened in us the belief in redemption because of the merits of the Tzadikim and the founders of Hassidism. He led collective conversations and also conversed with each of us individually. Reb Samuel took it upon himself to be the spiritual leader during our denigrated life and despairing moments.

Reb Samuel had an extraordinary personality and a wonderful disposition. He lived in Rzeszow where he had left his family. He was about forty or forty–five years old, a great scholar, pious and a strict observant of all the commandments even when it caused him pain. What he allowed others, he did not allow himself. His memory was astonishing. He never forgot anything he learned. He remembered entire Talmudical tractates, the Psalms, etc.

During the eleven months that we were together, he had not eaten anything besides bread and water. The rest of the observant inmates ate everything except for cooked meat. Although our menu did not contain meat, if the soup had any meaty taste, we refused to eat it. Reb Samuel succeeded in uniting around him a group of twelve young people who did not eat chometz on Passover.

Reb Samuel believed that the troubles that befell the Jews were pains before the final redemption. He was an admirer of the rabbi from Koloszyce. He strongly opposed Zionism. He taught us daily from his memory a chapter of Mishnayoth or a chapter of Gemara. We prayed daily with a minyan and our cell served as a spiritual centre for the entire prison. He made sure that we would remember at least one section of prayers in case we were the last Jews to survive.

“Who knows”, he said: “If we are not the last Jews alive, upon who was imposed the task of carrying on the Jewish spark?” he urged us not to be frightened of any sacrifice and that “keeping the fire burning on G–d's altar was not easy”. “I am convinced” he continued, “that the prayers that we pray daily from our hearts to the creator and the acceptance of the yoke of His Kingdom will be our shield and our sword”. His ornate thoughts were divulged in secret to his closest friends only. “No matter what! I have to write prayer books by hand and prepare a calendar for several years ahead so that, Heaven forbid, you shall not desecrate the High Holidays or the regular holidays until G–d will have mercy upon us and enable us to live as true Jews, in body and soul”.

“Who knows if I will be still around? I doubt if I will be worthy of surviving”. We sat for hours figuring out all the details of how to fulfil Reb Samuel's wish, how to supply him with paper, pen and ink. It was not an easy task in prison.

Samuel Nachum took upon himself to supply the paper. The jail nurse related to him with a special respect. She called him: “the Jewish rabbi”. Reb Samuel exploited this relation and always asked her for a powder against headaches. He successfully hid the wrapping paper. (An inmate was not allowed to possess any paper). I stole a pen from the interrogator's desk during the long hours of my interrogations. We also found a way to obtain ink. In the hall of our jail, there was a desk at

[Page 361]

which the jailers used to sit and on that desk, there was an inkwell. Before going out for our daily walks, we prepared small pieces of cotton. The custom was that we were escorted by two jailers ahead of us and two in the back. When we passed the desk, we dipped the cotton in the inkwell and, upon returning to our cell, we added a few drops of water to it in a cup and so we had ink. Of course, all the activities were carefully executed because being caught committing such a crime could have brought upon us heavy punishment. To ensure complete secrecy, we hid the writing materials inside a broom which was made from willow twigs. Nobody would have thought to look in such a place. With revered piety and fear for the authorities, but anxious for the mitzvah, Reb Samuel sat down in a corner and began to print with small print on pages the size of 5x7cm. Reb Samuel Nachum sat days and nights and did the holy work. His pupil watched the door with alert and would notify him when the guard was approaching. Two months of vigorous work ended when prayer books containing the entire weekly and holiday prayers, the “Amidah” for Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur and even Akdamuth for Shavuot were before us. Lon Lag B–omer, we prepared ourselves for a modest celebration – the receiving of the “Sidurim”. Reb Samuel's face glowed with happiness. We all became emotional. We gathered in a corner and Reb Samuel turned to us with a trembling voice: “Dear children”, he said and tears began to flow from his eyes. Filled with emotion, we joined him in cries that tore at our hearts. Cries that were choked before they could be heard for fear of being heard by the guards. We were grasped with the holy atmosphere of the Judgment Day as though we were preparing to establish the foundation of our People's continuity and deciding who shall live and who shall die. Reb Samuel Nachum continued with a choking voice. “In these days, when Jewish blood became worthless, who knows if anybody still remained there that could join us in our crying? We were separated from everyone who was dear to us, from parents, mothers, brothers and sisters, women and infants”. At this point, he strengthened his voice: “My heart is tearing apart when I realize that a big part of our nation could have saved their lives if they would have listened to the beat of salvation… I have to confess that a big part of our nation is guilty in our tragedy. We have not understood and have refused to respond to the call of the few on the rebuilding of our homeland. We postponed our redemption with our own hands. And now!” Here he turned to the younger segment: “I don't know if I will merit entering again into G–d's congregation but you probably will, I believe. Please! When the times come, abandon the Diaspora. Do not remain in strange lands even at physical cost. For Heaven's sake, remove all the bounds with the bitter Diaspora and establish a new life in the Holy Land and with it, you will speed up the complete redemption for you and for future generations”.

With trembling hands, Reb Samuel Nachum handed the Sidurim to everyone in the group and said: “That is our most precious treasure – the prayers in which we spill our hearts out before the Creator of the World. These Sidurim that I am handing over to you should accompany you wherever

[Page 362]

|

|

| |

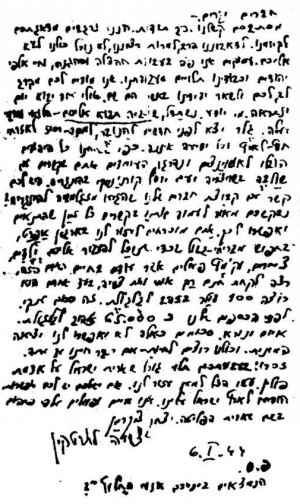

| This is the title page of Reb Samuel Nachum's prayer book with the dedication to Sicha Langzam: “This prayer book I wrote as a gift for my dynamic friend, the revered and accomplished young man, Simcha Langsam, when we were imprisoned in Zitomir, Russia in 1940.

G–d shall bring us out from here and bestow upon us a complete redemption.

Samuel Nachum Emer

From Rzeszow

|

[Page 363]

you go until the Redeemer will come and redeem the remainder of Israel”.

Reb Samuel Nachum opened the last Siddur and requested us to repeat after him. He began to recite the prayer “Avinu Malkeinu”. When he reached the verse: “G–d our King, have pity over us and over our babies and small children. Dot it for the sake of those who perished by fire and water for the sanctification of Thy Name”, he loudly began to wail. However, he was compelled to stop for fear of the authorities. “How hard it is”, he said. “The fact that we cannot even cry aloud. There is nothing harder and more painful than that which we cannot do whilst others are allowed to do. Nevertheless, boys, this is the greatness of the Jewish people. In every generation they rise up to annihilate us and the Holy blessed be He, saves us from their hands. All shades of Hamans impose upon us physical and spiritual decrees, mock us and scorn us among the nations, gloom our skies, darken our days and it seems as if the end has come. But at these times, our people exalt themselves heroically with the highest exaltation and exemplary self–sacrifice. They escape the different furnaces even though wounded and injured, but strong in their belief that they must produce from amongst themselves, redeemers and deliverers, to prove to the wicked world, that in spite of everything, the People of Israel must live and exist. Go forward powerfully and you will be helped”.

After the ceremony, I stood silent for a few seconds with my prayer book that I had just received. In my mind, my father's image appeared – Reb Yacov, the son of Tzvi Elimelech, a descendant of the rabbi Tzvi Elimelech Shapiro Dynasty from Dynow. I remembered the last few hours in our house before our separation as he stood before me. His tender white forehead, his long golden and slightly curled beard that adorned his sad face, and the tears that were flowing from his eyes. With trembling hands, he handed us the tefilin and the prayer books to pack among or belongings. The echoes of the words that came out of his mouth when he handed the tefilin to my brother Yechezkiel and me were still in my ears. “My sons, most beloved and dear to me! Every time when trouble befalls us, our nation becomes weaker. It is the duty of every Jew to block it and fence it off. I fear, my sons that Heaven forbid… (he had trouble finishing his sentence). “A need will arise that you will have to sacrifice your lives for 'Yiddishkeit'. Remember, do no separate from the tefilin. If you will guard them, they will guard you”. We kissed and embraced with extra love, and his tears kept flowing down his cheeks as though he wanted to implant upon us his thoughts and engrave them in our memory.

These memories came to my mind in that moment when I pressed the new prayer book to my heart with its small pages and miniature letters which was written by Reb Samuel Nachum Emer. May their memory be blessed.

G–d has privileged me to build my house in the State of Israel where I came to rest and put down my roots. I was privileged to bring with me the prayer book which accompanied me throughout the waste plains of Siberia and to exhibit it in the Generation–to–Generation Museum which is located in Heichal Shlomo in Jerusalem.

In this memorial book which perpetuates all the holy and untainted souls from our city, I would also like to commemorate the beloved exalted,

[Page 364]

and untainted soul of Reb Samuel Nachum Emer, of blessed memory. May he always be remembered. Amen.

Ben Zion Kalb saved many

Jewish lives during the Holocaust

by Shlomo Yahalomi

In this short article I would like to write a wonderful chapter which deserves to be glorified because the main hero is a native of Strzyzow. Ben Zion Kalb, the son of Reb Abraham Kalb, of blessed memory. This story is about the rescue of thousands of Jewish people from brutal killing by the Nazi – may their names be obliterated. This story deserved to be written in a more revered space in our book and in a more detailed way because of its importance, not only for the people of Strzyzow but also for the history of the Holocaust and the rescuers of Jews in general. However, for reasons that I cannot bring forth there, I received this material at the last moment when this book was almost finished. It was the will of the Divine Providence that Ben Zion, the friend of my youthful years when we sat and studied together in the Beit HaMidrash and fought the battle of Torah, came for a short visit to Israel. Only then did I convince him that these rescue stories should be told. Henceforth, I received this material from him with some pictures. For lack of time and space, I could not publish everything, only the most important facts. I feel obliged to point out that besides the letters and documents that I saw, and of which a few copies were included in this book, like the confirmation of the Jewish Agency, the letter from the Rabbi of Bobow and also the letters from Rabbi Micha Dov Weismandel, of blessed memory, Izhok Zukerman and others. I myself interviewed a few people who live with us in Israel who witnessed the rescue activity and they confirmed the truthfulness of this story.

The war caught up with Ben Zion Kalb, his brother Mendel and his parents in Nowy Targ. They moved there from Strzyzow over forty years ago. (Approximately in the late 20's). Two months after the outbreak of the war, he concluded that there was no future in Poland and decided to escape before it was too late. He obtained travel documents to Altendorf, Slovakia and from there he went to Kazmark. In Slovakia, Jews were relatively free and they thought that the wickedness would not reach them. To make a living, people smuggled wares and foreign currency across the border. Ben Zion was forced to do the same thing and therefore had constant contact with occupied Poland. Thanks to this contact, he knew what was happening to his brothers, the children of Israel and the fate that awaited them in the future. He knew that not only the German Nazi but the Poles too were eternal haters of the Jews and were waiting for the occasion to get rid of them. Ben Zion tried to take his parents and brother, Mendel out, but his parents refused to leave and Mendel refused to leave his parents. Consequently, Mendel was murdered in Rabka on July 21, 1942 and the parents in August, 1942.

When the situation in Slovakia worsened as well and the Nazi began to send Jews to work, Ben Zion claimed that this was not work, it was death.

[Page 365]

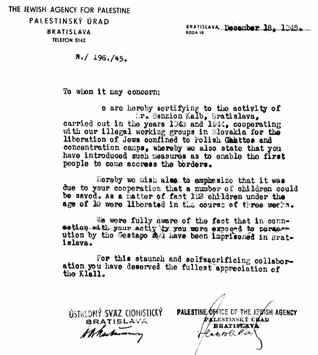

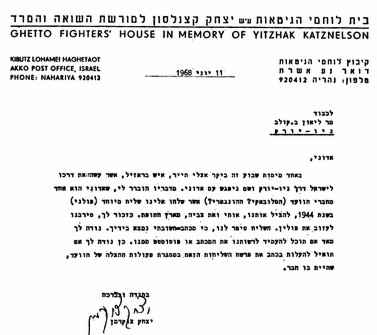

Letter from the Jewish Agency

|

|

| The Jewish Agency for Palestine |

| Palestinsky Urad |

Bratislava, December 18, 1945 |

| Bratislava |

……… |

| Telefon ……. |

| N/196./45. |

To whom it may concern:

We are hereby certifying the activity of Mr. Benzion Kalb, Bratislava, carried out in the years 1943 and 1944, cooperating with our illegal working groups in Slovakia for the liberation of Jews confined to Polish Ghettoes and concentration camps, whereby we also state that you have introduced such measures as to enable the first people to come across the borders.

Hereby we wish also to emphasize that it was due to your cooperation that a number of children could be saved. As a matter of fact, 103 children under the age of 30 were liberated in the course of three weeks.

We were fully aware of the fact that in connection with your activity you were exposed to persecution by the Gestapo and have been imprisoned in Bratislava.

For this stannah and self– sacrificing collaboration, you have deserved the fullest appreciation of the Klall. |

| |

| Ustridry Svaz Cionistky |

Palestine Office of the Jewish Agency |

| Bratislavk |

Palestinski Urad |

| |

Bratislvka |

|

[Page 366]

However, few believed him. The majority helped to send their children to “work” to Auschwitz. Ben Zion did not let the community leaders rest and he finally convinced them to start an urgent rescue operation. Thanks to his business contacts with non–Jews in Poland, he was able to dream about a widespread rescue operation with the help of his non–Jewish messengers. With the help of one righteous gentile, Jan Malec from Zefisco (then Poland and now belonging to Slovakia), and some other means, Ben Zion succeeded in bringing over to Slovakia three thousand people, including two hundred children aged two months to six years. This was a dangerous action. Once Ben Zion travelled with his gentile helpers and was arrested and held in prison for two weeks. Miraculously he escaped. He was in hiding for six months in a cellar and had gone through hell. (G–d willing, we will tell about these events in a separate book which I hope to publish). More than once, he was forced to leave the children alone in the woods for the night and the next day he had to search for them and found them almost frozen to death. Several times, they were almost caught by the Nazi but the gentile Jan Malec, who knew all the pathways in the woods, succeeded in bringing them out undetected.

Of course, just by bringing the children over from Poland to Slovakia, the rescue action was not complete. We knew that the wickedness would reach Slovakia as well. But when? Maybe soon? Again, much devotion and work was needed to complete the job. Almost every transport of children had to be hidden among the gentiles until safe houses were found for them. And here, I would like to mention favourably Mrs. Bartoshek, a gentile woman in whose house Ben Zion Kalb hid and through whose husband he sent letters to the rabbi, the famous rescuer Reb Micha Dov Weismandel, the author of Min Hameizar and Reb Shlomo Stern. Rabbi Weismandel put him in contact with the underground organizations that participated in the rescue operation. Members of that organization were, among others, Mrs. Fleishman, the famous heroine; Dr. Newman; Dr. Duks; Ben Zion Gotlieb from the Mizrachi; Egan Roth and Mr. Korminski. When Ben Zio n returned from Poland and described the hopeless situation there, at first they did not believe him. Even those who did believe did not know how serious the situation was. It is interesting to quote an excerpt from a letter written by Rabbi Weismandel to Ben Zion: “Please, do whatever is possible to put the children who have just reached you into kosher homes, truly pious so that Heaven forbid we should not lose them to strangers. They are the few who are left and we shall watch over them that they remain pious with G–d's help”. However, Ben Zion did not heed his advice. On the contrary, he did the opposite. He understood that in non–Jewish homes the children would be safer. But he also hid some children in Jewish homes. Ben Zion Kalb was in contact with Jewish leaders in Pressburg and he pressured them to help bring over more Jews. The people from Pressburg contacted Switzerland, the United States and Eretz Israel. Great sums of money were needed. Dr. Wallstein, who now lives in Israel, took care of the finances. In his continuing efforts in the rescue operation from Poland, Ben Zion Kalb organized the smuggling of many Jews from Slovakia to Budapest, Hungary, through Preshov and Kashau. There the Jews joined a Polish organization pretending to be gentiles,

[Page 367]

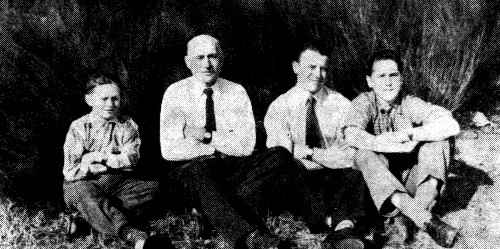

|

|

| The second from left is Jan Malec, the most important messenger in the rescue operation. He himself rescued 635 people including 200 orphans.

At his right is his son, and at his left are his relatives. |

[Page 368]

Until ten years after the war. What a pity that there is no list of the survivors who went through this smuggling route. I would like only to mention a few of them. The first survivor was Ben Zion's bride, Clara Lieber. After super–human efforts, Ben Zion finally located her and kept contact with her. In one letter, she wrote to him that if he would not sent Jan Malec (the gentile chief smuggler), she would travel to his brother Mendel. (Which meant she would be killed). She was in Bochnia. Her rescue was very expensive. She was the first who dared to go and she showed a dangerous way on how to leave Bochnia. After her successful escape, many followed her. Subsequently, it was enough to pay the smugglers between ten and eighty dollars per head. Persons who had money paid and if not, others paid for them. Many times Ben Zion paid out of his own pocket. Other survivors were: Rabbi Shlomo Halberstam from Bobow; his brother Reb Yechezkiel; the son of Reb Moshe Stempel who was Reb Feivel Stempel's and the old Rabbi from Bobow's grandson. He now lives in London and is the head of a Yeshiva. The police tried to stop their car and shot at them. With them were six more children – the children of the Rabbi from Sucha who was the grandson of the Rabbi from Sandz. Reb Moshe Shenfeld, the son–in–law of Reb Itzhok Meir Levin; Eliezer Unger; two sons of Mordechai Weinberg from Krakow (who was the son of Reb Berish, a famous Hassid and a wealthy man in Krakow. The sons of Reb Mordechai Weinberg now live in Israel and they served in the Israeli Army and Navy. Their uncle, Reb Joel Kremer told me about them. Also rescued were the Smith sisters, relatives of Reb Moshe Bleicher; the assistant rabbi in Krakow and Eva Eckstein from Rzeszow. Reb Jonah Eckstein and Mrs. Stern took care of the children until they were safe.

Had there been enough money, it would have been possible to save many more children. On the next pages, there is a letter from “Antek” – Itzhok Zukerman and Tzivia Lubetkin who confirm this fact. The above were ghetto leaders in Poland. Ben Zion Kalb also suggested helping them to escape but they refused. They refused to abandon their brothers. Dr. Bornstein, who is at present head of the Neurological Department of the Beilinson Hospital, told my wife that Ben Zion had proposed to help him escape but he refused to leave his wife behind. Many other famous people have given testimony that Ben Zion Kalb had rescued many lives. The last but not least of witnesses is the present Rabbi of Bobow, Rabbi Shlomo Halberstam who called him: “the war hero in the field of saving Jewish lives”. As indicated at the beginning of this article, this is only a synopsis but a highly qualitative chapter for which I would like to be credited as publicizing the deed of Ben Zion Kalb in this book. This article came about as a result of applying a little pressure after which he agreed to tell me a few details about his activity, accompanied with documents verifying what he had told me.

I would like to add that it is an honour for our shtetl that, not only did no one collaborate, Heaven forbid, with the Nazi but they were willing to sacrifice their lives for the rescue of our brethren – the pursued and afflicted. I want to point out that Ben Zion was not the only one with such deeds. There were other natives from Strzyzow who were active after the Holocaust in the rescue of Jewish children from gentile

[Page 369]

hands. About that rescue, Itzhok Berglass wrote in another place.

And the holy martyr, dear Reb Mendel Groskopf, our landsman who the Nazi nominated as head of the “Judenrat” in Brzostek where he lived, handed over a list with one name only: His own. He overcame temptation and refused to deliver Jews into the damned, wicked hands… He was murdered on the spot. He was the first martyred victim and he surely bequeathed much honour on our shtetl.

Letter from Rabbi Weismandel to Ben Zion Kalb

Blessed be He

Friday, Chapter of the week: ”Ki Tetzeh” 1942.

Peace and blessing to my charming friend who pursues justice and kindness, Mr. Ben Zion Kalb. May his candle continue to burn!

I received your letter. And what can I say? What can I tell? We are facing destruction. We should all say: “We are to be blamed” because there was a time when we could rescue many more if we would have had the funds. My heart and body are broken in fragments. And now I plead with you, do whatever is possible to rescue what is left. Maybe you still have some means left? In the time of fury we think that all is lost. But later it appears that there is still a few who were in hiding and can be rescued. Therefore, we need immediate transport. We need messengers to appraise the situation, to see what can be done. You should contact Mr. Grayer, may his candle continue to burn. He might advise how it may be done and the Almighty will assist, protect and help.

One more favour I would like to ask. Please, do whatever is possible to put the children in kosher homes because they come from truly pious people, in order to keep them from strange hands. The children are the few that are left to us and we are obligated to see that they remain pious until the complete redemption will arrive.

I will be waiting for a response. Give regards to Yechezkiel; Mr Grayer; Mr. Berger; Reb Joseph and all the rest who are involved in this big, holy mitzvah.

Your friend

Micha Dov

[Page 370]

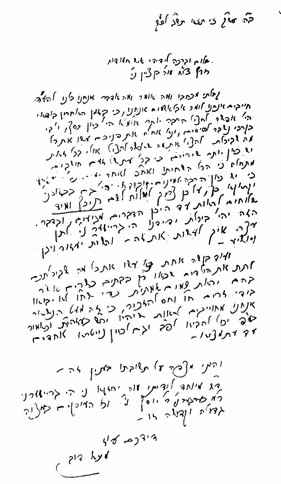

|

|

| Copy of Rabbi Weismandel's letter |

[Page 371]

|

|

|

|

Ben Zion Kalb with Reb Mordechai

Weinberg's two sons that he rescued |

|

Clara Lieber, Ben Zion Kalb's bride |

| |

|

|

|

|

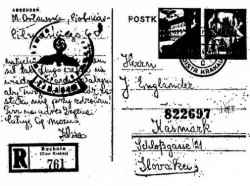

| A postcard from the Valley of Death |

[Page 372]

|

|

| A group of children rescued by Ben Zion Kalb

The adults: standing from left to right are: Eva Ekstein, Jonah Ekstein and Mrs. Stern who took care of the children |

|

|

| Two children who were rescued by Ben Zion Kalb and Mrs. Stern |

[Page 373]

|

|

| Original letter from Itzhok Zukerman and Tzivia Lubetkin |

[Page 374]

A postcard from the valley of death

February 23, 1943.

My dearest!

Last night I received your postcard which wandered a week or more to find me. I was not able to describe my happiness. I am still perplexed. Apparently, as you did not expect to hear from me, so did I not expect to hear from you. But let us get serious. As you see, I am, thank G–d, well but the physical conditions are very hard. My girlfriend received Hungarian citizenship from her relatives and, therefore, her condition has improved a lot. If you could do the same, it would help me too. I have nothing more to write about except that I very much miss you. Now that I know that you are well, I would very much like to see you. When you will write to your friend Jasiek, who brought me once the silk stockings, ask him in my name to come to see me. I have a lot to tell him. I am concluding my writing with the plea – try and respond immediately. Do not let me wait. Write to the same address and I hope it will reach me in the same situation that I am now.

Kisses, Clara

Letters to Ben Zion Kalb from Taivia Lubetkin

and “Antek” Itzhok Zukerman, leaders in the Warsaw ghetto

Dear Comrades!

We received your letters. Many thanks. We were moved about your worry for our existence. Regrettably, notwithstanding our willingness, all of us cannot come to you. We are busy here with rescue activities and defence. The lives of thousands of Jews and our self–respect depend on our work. We thank you and all the rest of our friends wherever they are, from the bottom of our hearts. Maybe the day will come and we will see each other. Who knows? We will try that…(name unreadable) should come to you accompanied by Mordechai, her husband. Geller left two months ago to Hanover to a concentration camp for foreign citizens. So far, we have no information of his whereabouts. What we heard is that they all went to Auschwitz and were killed there. Do you have contact with Schwalbe in Switzerland or Joseph Katyanski in Hungary? Have you any contact with a group of comrades of ours from Zaglebie who should have arrived in Hungary? Lease, contact us whenever it is possible. You must help us to organize a staff, to search for border smugglers to enable us to transport children who are still alive. The man who was sent by you to take me and Tzivia wanted to take us for free but as to the others, he demanded one hundred dollars in gold for each person. This is a huge sum. It comes to sixty five thousand zlotys in our currency per head. This is awful and terrible. For such a price, not many

[Page 375]

|

|

| Letter from Izhok Zukerman “Antek” to Ben Zion Kalb |

[Page 376]

|

|

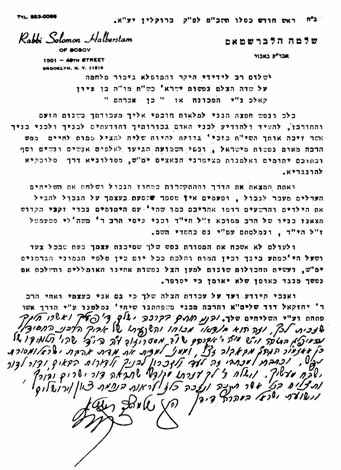

| Letter from the Rabbi of Bobov to Ben Zion Kalb |

[Page 377]

[continuation from page 374] can escape. But everyone who survived until now wants to escape. Remember! The lives of the remnants of Israel in Poland depend on your activity. Do whatever is possible to help us. If you can, inform Eretz Israel about us. We live and act however we can.

In the name of the remaining survivors.

Itzhok Zukerman (Antek) and Tzivia Lubetkin.

From the ghetto house in memory of Itzhok Katznelson

To the revered Mr. Ben Zion Kalb in New York.

Sir!

A tourist from Brazil, who came to Israel via New York where he met you, paid us a visit this week. From his statement it became clear to me that you were one of the Slovakian–Hungarian committee members who sent to us a special messenger in 1944. That man told me that you possess the response letter. We would be grateful if you could send us a photocopy of that letter. We would also be grateful if you would be willing to put into writing the details of that part of the action within the frame of the general activity of the rescue committee of which you were a member.

With thanks and blessing.

Itzhok Zukerman (Antek)

Rosh Chodesh Kislev, 1969.

Blessed be His Name

From Rabbi Shlomo Halberstam of Bobov

1501–48th street, Brooklyn, New York.

Great peace for my dear friend, the marvellous war hero in the field of the rescue of Jewish lives, Mr. Ben Zion Kalb, whose pseudonym then was “Ben Abraham”. May his candle keep burning.

It is my desire with all my heart and soul to repay my debt to you for your work in the years of fury and destruction, to testify and inform mankind of your heroism. To inform the children and grandchildren that you were merited by the blessed Name with such great merits to be the saviour of many hundreds of Jewish lives. According to information I have received, thousands of men, women and children from Poland escaped via Slovakia to Hungary from the Nazi claws, may their names be obliterated.

You found a path and contacts in the border area. You sent gentile messengers across the border. And many times you travelled by yourself to the border to rescue children from villains, and they pursued you.

[Page 378]

as with the orphans of my holy grandfather from Sandz, the boys of the Rabbi from Sucha, may G–d avenge his blood. Also with the sons of my brother–in–law, Reb Moshele Stempel, of blessed memory. You successfully escaped, miraculously and by the grace of G–d.

I will never forget your devotion to the cause, putting yourself in a dangerous and life–threatening situation where, in your every stride or step, there was only a thin thread between life and death. You walked daily among the hegemonic Germans, may their names be obliterated. You used different tricks in order to save the lives of our wretched brothers, putting your own life on the line in a way which is hard to believe when told.

And I am a witness to your rescue mission because I myself with my brother Yechezkiel David, shall he live, and many members of my family, escaped through the route that you opened and with the help of your messengers.

Behold I am signing off with a blessing. May G–d pay you for your deeds, blessed be your share for meriting it. And this came from the energy and instilment of your father, the Rabbinical Hassid distinguished in Torah and piousness, Reb Avrom the Shohet of Strzyzow, may G–d avenge his blood. Your father was a pupil of the holy and righteous one, the Rabbi of Bobow, of blessed memory. From him you learned the attributes of love for Israel and the devotion to Jewish souls. I wrote this letter as a testimony and remembrance for your sons and future generations. Each generation shall praise your deeds. G–d shall send you his holy help that you should live and bring forth an honest and blessed generation. May you succeed wherever you turn and we shall soon all merit to see the consolation of Zion and Jerusalem, the salvation of Israel. Amen.

[Page 379]

My last Simchat Torah in Strzyzow

by Harry (Yechezkiel) Langsam

The last High Holidays which are called in Hebrew “Yamim Noraim”, the Days of Awe, were truly awful days. They were filled with fear for the rapacious Nazi animal that had just recently completed the occupation of Poland.

When World War II began, I resided in Tarnow where I was working in a paper bag factory. My brother Simcha and I were expecting to hear from our father, of blessed memory, who remained in Strzyzow. But, having no news about his well–being troubled us immensely and we therefore decided that I should try to reach Strzyzow by foot, ignoring the danger that hovered over a Jewish boy wandering through villages void of Jews.

I knew the road from before the war when I had travelled by horse and buggy with Reb Leibush Diamand. I dressed up in peasant clothes so as not to arouse suspicion. I left on my journey heading for Strzyzow. From Tarnow I went to Pilzno, then to Brzostek, Frysztak and into Strzyzow, a distance of fifty miles. The road was peaceful without any unpleasantness. Between Pilzno and Brzostek, I lodged in a Jewish house. At first the owner refused to let me stay because of the orders of the Gestapo which forbad lodging to strangers. But I had no choice. I could not continue because of the seven o'clock curfew. The man risked his life and let me stay. It was Friday morning, Hashanah Raba, when I reached Brzostek and went into the house of Reb Mendel Groskopf who was a native of Strzyzow. (In another part of this book, his heroic death for the sanctification of G–d's name was described in detail). We prayed the morning prayers and I witnessed a heart–breaking scene when Reb Mendel put on the table a dried–up lulav from last year in commemoration of better times. Everyone cried bitterly remembering those previous holidays. I reached Strzyzow at three o'clock that afternoon.

In the evening, it was Shemini Atzeret Eve and we gathered in the house of Michael Schitz to conduct the services and make the Hakafot which resembled more closely to prayers in a mourner's house than to the festivities of earlier years. My heart ached when I recalled the joyous Hakafot, the colourful flags with the red apples and the burning candles on their tops, the exaltation with which Rabbi Nechemiah Shapiro had conducted the Hakafot and the children pushing each other in order to be able to kiss the little Torah scroll with which the Rabbi made the Hakafot. With love and devotion did the Rabbi bend down to each child, trying not to miss anyone. The Rabbi had a special affection for his little Torah scroll and never separated from it. He ordered a special suitcase and wherever he travelled, the Torah was always with him.

We felt that under the brutal rule of the Nazi who flooded us with a sea of hatred, it would be impossible to live. The Jews were not liked

[Page 380]

before, but now we were abandoned altogether. For that reason, we decided to leave Strzyzow after the holidays, to leave this damned land and wander off to the eastern part of Poland which was occupied by the Soviets and where, at that time, Jews were not oppressed. On Tuesday, October 25th, 1939 my brother and I left our home, our birthplace, with the hope that we would return shortly and find everybody safe.

When we left rain was pouring as it usually did in that part of Europe. It seemed that nature was crying with us. I looked around, stared at the house where I was born, at the muddy alley and bid farewell in my thoughts to my shtetl and its wonderful scenery, the hills, the groves, the river and also to her Jews and to the very few good gentiles. I also summed up and recalled the pain I had gone through in this place. There were also some good and happy times, but not too many.

We were frightened of the unknown road which we still had to pass under the German rule. The life–threatening danger was immense. On the other hand, we were scared of the life under the strict Soviet regime. We cursed all those who had brought such misfortune upon us. Our father, of blessed memory, escorted us a short distance and expressed his wishes to see us back home soon for the Passover Seder. To our sorrow, that was the last time we saw our father and we never saw the rest of our family who remained under the German occupation.

Memories from the days of horror

Jumping off the death–train

by Itzhok Leib Rosen

Midnight, November 15–16, 1942. We were transported by train to the annihilation camp. The train consisted of twenty–one cattle cars. Fourteen cars came from Bochnia and Tarnow and seven cars with Jews from the ghetto in Rzeszow were attached at the railroad station in Rzeszow. Each car contained approximately one hundred and fifty people. With us were the last members of the Judenrat from Strzyzow – Abraham Brav and Sheingal and also Samuel (Mulik) Feit and Chaim Adest, both from Strzyzow.

When we passed the village of Krasna, about thirteen kilometres from Rzeszow, an older man from Bochnia rose, a man who had already experienced several escapes from death–trains, and uttered these words: “Fools! Why are you standing here? Where do you think they are taking you?” And he forced his way to the small opening, pulled out a pair of pliers hidden in his boots and cut the barbed wire that covered the opening. The man jumped out and, thanks to him, we also jumped.

It tears my heart apart when I think about these two people from Strzyzow – Mulik Feit and Chaim Adest, a boy as tall and as strong as a tree. I begged them: “Jump!” but they refused. What a pity. The poor souls did not believe that they were being led to their deaths. I myself was afraid to jump but I heard my brother Samuel shouting from the outside. He had already jumped so I instinctively followed him. Mulik Feit yelled after me. I heard him very clearly: “Take care of my child!” His younger daughter Hena was still in the ghetto.

[Page 381]

Among the escapees was a young boy from Lutcza and Mr. Yaffe from Czudec, in the vicinity of Strzyzow. The boy disappeared immediately and I later found out that he did not survive. In the early morning we went into a barn, gave the peasant five hundred zlotys and were given a bowl of soup each and a bottle of home brew. In the afternoon, the peasant scolded us and demanded that we leave his premises immediately because German policemen had arrived in the village. This was not true but we had no choice. We had to leave. We decided to return to the ghetto in Rzeszow. The peasant directed us to the highway leading to Rzeszow. We walked toward the ghetto and nobody noticed us.

Before entering the ghetto, Mr. Yaffe wanted to stop at a gentile friend's house. However, we did not find him home. His wife was very frightened and told us to hide in the pig–pen where we spent a few hours. Meanwhile, the woman went to look for her husband whom she found in a salon and he came home dead drunk. He took us out from the pig–en and asked us to lie down on his bed, but we refused. We spent the night in deadly fear and in the early morning, the man sent his wife and six children into the street to see if it was safe. We followed them and jumped over the fence of a house which belonged to the famous jeweller, Zuker, into the ghetto. In the ghetto we encountered one hundred and fifty people who had jumped from the train that night but the man from Bochnia who had cut the wire was not among them.

We lived in the ghetto until May 1943. Much has been written already about our lives in the ghetto and the bitter experience we went through. I would like only to mention one episode:

A Polish officer by the name of Pasek helped us contact our sister Pearl who lived in Berlin on Aryan documents. During the time that we spent in the ghetto, we had received about ten letters. We received each letter in mortal terror and we thanked the Almighty that they had not fallen into the hands of the Gestapo. We were lucky that there were no Jewish informers in the ghetto.

Although it is very depressing to reminisce about these troubled times, on the other hand, it relieves a burden from my heart.

The struggle with the Jewish “Kapos”

by Itzhok Leib Rosen

After the great expulsion from the ghetto in Rzeszow, which took place on November 15, 1942 only four thousand people remained in the ghetto. One day upon returning from work outside the ghetto, we noticed an excited crow that was milling around one area of the ghetto. This part of the ghetto was called “Drukerruvka”. The Kapos were extorting contributions from everyone. When I came closer I was hit in the face by a Kapo's whip. The Kapo was a local Jew from Rzeszow – Mr. Kleinmintz. There were not many local Jewish Kapos anymore. Most Kapos were from Lodz and Kalisz. Not realizing what I was doing, I hit him back and he fell. I quickly ran home but mistakenly entered another house where I encountered a few more Jewish policemen, including the sadly infamous “Itchele” from Kolbuszowa. I hit him too and he fell down the stairs.

I was finally overpowered by a few policemen and taken to the German

[Page 382]

command post which was located in the same building as the Judenrat.

The entire ghetto was in uproar. It seemed like a revolt. Luckily there were no Germans in the ghetto when I was brought there. While I was led by the policemen, we encountered Mr. Lubasz, a well–known and beloved Jew in the Rzeszow ghetto. The man knew me from before the war. He calmed down the placement and he followed us until we reached the Judenrat. Meanwhile, as I found out later, other policemen caught my younger brother Samuel who was only fifteen years old and they took revenge on him by beating him savagely. When we came into the Judenrat, Abraham Brav and Sheingal, the two remaining members of the Judenrat in Strzyzow and also members of the Rzeszow Judenrat, happened to be there. They saved my life by taking me out of the hands of the placement because by then, German policemen had arrived in the ghetto. Brav and Sheingal locked me up in the office of Dr. Kleinman, the chairman of the Judenrat, and kept me there for an hour until the arrival of Dr. Kleinman. Faking anger, Dr. Kleinman scolded me. I denied and showed a receipt proving that my contribution had been paid. And that is how the matter ended. My brother and I realized that our lives had been saved by a miracle.

My second encounter with a Kapo occurred in Huta Komarowska camp. This camp was under the command of the German commander – Shubke – who was not a bad man. When a group of people were sent to Strzyzow to work there, demolishing unused barracks, they bartered some clothes for food and he was forced to arrest us at the insistence of the local gentiles. He was afraid that the local gentiles might report him to higher authorities. But after he was convinced that all the gentiles were interested in was taking the food away from us and that they had no intention of pursuing the matter further, he immediately released us. However, there was one commandant in the Huta Komarowska camp – the infamous Schmidt (whose trial is taking place right now in a German court). He was helped in his cruelty by the Jewish Kapos – the brothers Rybner, Mr. Straucher, Elimelech Kirschenbaum and others. We worked very hard cutting timber and during the work we were brutally tortured by this commandant and his helpers, the Kapos. Once we complained to commandant Shubke and he called in the Kapos and reprimanded them for their bad treatment. The next day the Kapos were mad at us and took revenge. They ordered that every second day would be penalty day, which meant working without food and without our shirts at a time when the mosquitoes were sucking our last drop of blood. If someone attempted to straighten his back or stopped working for one second, he was beaten with a truncheon over his back. The worst of them all was Elimelech Kirschenbaum. He was later shot by the Russians. Once, when he came near my brother Samuel and raised his truncheon, I jumped close to him with the axe in my hand and said to him: “Elimelech – if you touch my brother your end will be right here”. My anger affected him. He let go of my brother but he threatened that he would settle with me when we returned to the camp.

While walking back to the camp we searched our souls for advice. “Should we try to escape or not? What should we do?” We also shared our thoughts and wanted to hear the opinion of my older brother, Yechiel,

[Page 383]

and Mendel Lieberman, the son of David Lieberman from Strzyzow. The brother of the Kapo, a fine young man (he now lives in Israel), advised us not to run. There was nowhere to run. The Poles were pursuing every Jew. This man kept scolding and reprimanding his brother the Kapo all the way back to camp until the Kapo finally agreed to swallow his pride and not report the incident to the commandant. And that is how the problem was solved and we were saved again.

“Yiddishkeit” in the German concentration camps

by Itzhok Leib Rosen

Excerpt from a letter written in Sao Paulo, Brazil. 10th day of Kislev, November 15th, 1964.

Today is Sunday and we have the day off. It is also November 15th when Brazil celebrates Independence Day. I remember that twenty–two years ago, on November 15th, 1050 Jews were sent away. My brother Samuel and I were among them. Abraham Brav, Samuel Feit and a few more from Strzyzow were also in that transport.

Yes, my friends, one cannot forget, especially we who suffered will remember for ever what we went through and what we witnessed. These memories will be with us until the last day of our lives.

Now, if you wonder whether we had tefilin in the camps? Yes. I remember very well. I had my tefilin which I received on my Bar Mitzva day. I took them with me to the ghetto in Rzeszow. In May, 1943, I brought them into the concentration camp. From Huta Komarowska we were transported to Kochanowka and were required to go naked through the disinfection chamber. We were ordered to hold our shoes over our heads. I hid my tefilin in the shoes and that is how I managed to bring them into the camp. We were assigned to block number 2. There were only two blocks each housing about two hundred and fifty Jews – a total of five hundred men.

Everyone in our block wanted to don the tefilin and pray in them but no one was anxious to risk his life by keeping them. For a whole month we spent nights donning the phylacteries, each person taking his turn. To avoid suspicion, we had to do it at night because at six in the morning, we had to appear for a head count. Until someone from the outside noticed that something suspicious was going on in our barracks. The Nazi chased everyone out, searched the barracks and found the crime. However, nobody said that the tefilin belonged to me. From that day (this was beginning of 1944) until liberation, we completely lost count of the Jewish calendar and almost forgot about Yiddishkeit. From Pustkow we were shipped to Plaszow, from there to Bochnia, onto Mielec and finally to Wieliczka. The Russians were closing in on the Germans but they did not let up on the victims. In Wieliczka we were slaving in the airplane factory which was located underground in a salt mine. However, the factory had very little success for the Germans.

From Wieliczka the German ran with us to Flosenburg and on to Limeritz in Czechoslovakia not far from Theresienstadt. There we met

[Page 384]

Mendel Lieberman and Nechemiah Felber from Strzyzow. Lieberman was sent to Dachau and I never saw him again. I met Felber again together with Wolf Mandel and Nechemiah Hauben from Strzyzow in one of the last and worst camp – Guzin 2 near Matthausen. All of them succumbed during the last horrible murder action, the so–called “Entlaussung” (disinfection).

Somehow we felt that the High Holidays were approaching but were not aware of the exact date. I dared and asked an S.S man if he happened to know when the Jewish New Year would be. He told me that not far away there were some Jews working from the Theresienstadt ghetto about whom we did not know.

One day I risked my life and secretly crawled over to that group from the Theresienstadt ghetto and asked them about the High Holidays. However they did not respond. I did not give up. On my third try the ghetto Jews threw me a little note that tomorrow would be Yom Kippur. That is how we found out the Jewish date. Since then, we kept track of the Jewish dates together with the troubles that had just begun anew because we were shipped to Matthausen (Murderhausen).

The horrible years. 1942–1945

By Hilda Mandel

daughter of Samuel (Mulik) Feit

As one of the few survivors of the Holocaust from Strzyzow, I was asked to contribute a few lines to describe my survival.

It is difficult for me to write about it and I never did until now. I always felt guilty for being the only one alive from my wonderful immediate family that consisted of my father Samuel (Mulik) Feit, my mother Rachel, sister Henia and brother Joseph. I am the older daughter Hinda, (Hilda) Mandel.

Let me begin from the time when my family was expelled to the Rzeszow ghetto in the summer of 1942. On arrival at Rzeszow we were put in a tiny and dark room with many other people. Shortly after, rumours started to spread about sending us to labour camps from which no one had returned. Daily, there were lists of people who were ordered to report and they were taken away to an unknown destination.

My father and I were taken each morning to a work brigade that was assigned to work on roads or railroads but we never worked together, always in separate places. We left the ghetto heavily guarded and returned in the evening. That lasted a couple of weeks. We also went through a selection (left meant immediate death and right a few more days to live).

One evening they announced that all women with children not yet thirteen years of age had to report in the morning. That meant my mother and my little brother Joseph. There was also a list with names to report and my name was on the list.

That evening my father, of blessed memory, gathered us together to say goodbye. However, he handed me a document of life which consisted of a birth certificate of a deceased Polish girl. He handed it over to

[Page 385]

me and said: “I hope with this document you will be able to survive. Take a chance”. He was able to secure this document while on work detail.

The next morning while we were being marched out of the ghetto to go to work and while crossing the fields, I simply left the ranks, rolled and rolled on the ground, hid in bushes and walked away. I still think to this day that G–d made the soldiers blind for the moment of my escape. I should say our escape because I had a companion. This was Pearl Rosen from Strzyzow.

While we were hiding, we saw a column of people – our brothers and sisters – being led to the railroad station and for the last time, I had a glimpse of my mother and brother being led to the trains.

We purchased tickets to Krakow and we were on our way. I had a friend from the gymnasium in Krakow who helped us finding a temporary job in a military hospital. At this time I assumed the name of Barbara Czapczynska which was on the birth certificate. After weeks of living in deadly fear of being discovered, we decided to volunteer for work in Germany. We were accepted and they shipped us to Berlin.

I stayed there for three years in the lion's den, working in an office until the end of the war. I know my description sounds cut and dry. However, this is only an outline of my survival from 1942 to 1945. A lot of suffering and pain, physical and emotional went into these years and after and it just never stops. I miss my parents, my sister and brother and I will to the end of my days.

I know we all have scars that never heal. I know I have.

May G–d avenge their untainted blood. They shall never be forgotten.

Surviving in the Lion's den

By Pearl Strengerwoski–Rosen

At the outbreak of World War II, my brothers and I with our mother, of blessed memory, were all living in Strzyzow except for our older brother, Yechiel who was mobilized in the Polish army to defend the “fatherland”. Soon thereafter, we lost trace of him and did not know whether he was alive or not.

When the situation became clear to us, that is, we began to hear what was happening to the Jews – being tormented and later annihilated, many of the younger people ran away wherever they could; many crossing the border to Soviet–occupied territory. Few Jews went into hiding but the majority remained in Strzyzow and resignedly waited their fate under the Nazi regime. Jews were exploited and used for hard, physical and denigrating work. The Germans needed cheap slave labour for their war machine. Our family remained in Strzyzow. My brother Itzhok Leib and I, with the youngest brother Samuel (Shmulik), took care of our sick mother. The burden of providing food for the family fell on the shoulders of my brother Itzhok Leib and me.

Meanwhile, we were informed by a messenger that my oldest brother was alive and hiding in a small town, Nowosielce, not far from the

[Page 386]

border town Sanok. I went there with my older brother's documents and brought him home. This was illegal and had to done secretly because the Germans grabbed all returnees from the Russian side and killed them as being communists. Luckily they did not find out about him and he survived. A short time later we were expelled to the Rzeszow ghetto together with the rest of the Jews from Strzyzow.

The situation in the ghetto became very difficult. The Germans concentrated Jews from the whole area into the ghetto. The Germans tormented the ghetto Jews and inflicted pain and suffering upon them. The poor suffered the most not having the means to obtain any food to sustain life. The daily life–threatening situation continued.

The Germans began to deport people to the annihilation camps. In one of the selections, I was among those to be shipped out. With great danger and difficulty, my friend Hinda Feit and I succeeded to escape from the ghetto and went to Krakow on Aryan documents. In Krakow we had a Christian friend, a classmate from school, who helped us find jobs as nurses in German hospitals. I worked in one hospital and Hinda in another. When it became dangerous to be recognized by someone from Strzyzow, we both “volunteered” to be sent to Germany for work.

With great hardship we finally reached Berlin, the lion's den. In Berlin my friend and I were separated and began working as clerks in an office because of our knowledge of the German language. This all happened in 1942.

Although we worked in separate places, we did manage to keep in contact. I saw before my eyes the Angel of Death many times. We were required to wear the letter “P” on our clothes as Polish slave labourers. Once I forgot to attach the letter to my clothes and it just so happened when an Allied air raid took place. Somebody reported me and I was summoned to a higher authority. Not knowing the reason why I was being summoned, I was very frightened. I was sure that I was discovered as a Jewess. I took farewell of my friend Hinda Feit and reluctantly went to report. I was sure that I would be killed. But when they asked me why I was not wearing the letter “P”, I breathed a sigh of relief, because I realized that for such an offence, the punishment was not so severe. There were many such instances when my life was hanging on a thread.

My friend and I were in Berlin until the end of the war. We lived through heavy bombardments and our lives were in great danger – ironically from friendly bombs. At the end of the war, we were perplexed. We did not know where to go or which way to turn. I decided to return home and search for my family. I jumped on the first freight train which was going in the direction of Poland. After eight days, I reached Rzeszow and was reunited with my oldest brother Yechiel and my dear friend, Hinda Feit.

I skipped many details about my travails during that period. I am simply unable physically to reminisce about this dreadful period and the tragic times for the Jews and in particular for me as an individual.

[Page 387]

“Kol Nidrei” in Auschwitz

By Joseph Weinberg

The sad days of the horrible autumn brought one plague after another. As soon as people arrived they immediately met their destiny. From the older numbers, there were few left. A wild craze dominated the Germans. The worse the news which came from the front, the wilder and more blood–thirsty they became. It seemed that they were taking revenge on us for their unfortunate defeats on the battlefield. Every few days they ordered us to run naked and the weak ones were picked for the ovens. They resigned victims apathetically went into the barracks from where they were taken to the ovens. The rest of us were resignedly trudging daily to–and–from slave labour. We knew that tomorrow or the next day we would share the same fate. Every day there were new arrivals. From all over Europe, wretched people were brought here for annihilation. We became used to the stench of burning bodies. It became part of the natural scenery of the wonderful surroundings. The beautiful mountains were like a crown for the camp. Every morning, dew covered the grass and from the nearby river, a whisper was heard in the still of the night as if it was bringing secrets from a distant world and from the starts in the skies. Trembling leaves on trees, crops in nearby fields were moving in harmony with the breeze and bright clouds which were created by the smoke that came out from the crematorium ovens all became one entity.

The beautiful scenery from the other side of the fence pained me. We were here where everything was dead. With deep resentment, I observed the fantastic sunset. Nature mocked our destiny. And so passed one frightful day after another. However, a sliver of hope was hidden deep in the heart. Maybe! I clung with the last threads to life. The day did not pass entirely without hope.

For several days, whispers reached us from the women's camp. They were not taken out to work anymore. They were locked up behind the barbed wires. Stories were circulating that many women were covered with scabies and a big selection took place. At night, wild wailing was heard as if thousands of people were being slaughtered. The German Kapos who knew what was going on told us that four thousand women were selected to be burned and were packed into one barrack naked. The women lay there one on top of another without food or water. They raised the roof with their bodies and the S.S. men kept shooting at them like rabbits.

That night we could not fall asleep. Next day was Yom Kippur Eve. Tragic were these days of awe!

In the morning we found out that Berlin had ordered not to burn the women but to heal their wounds. A small ray of hope stole into my heart. Maybe after all! After the evening count, we were supposed to gather for the Kol Nidrei prayer. We had promised ourselves for a long

[Page 388]

time that this year we would conduct Kol Nidrei services.

A thick fog covered the skies on that morning. The fog disappeared at noon and it began to rain. The sun was hidden in the clouds. Heaven cried all afternoon. Now, just before Kol Nidrei, the heavens calmed down a little bit. The rain stopped and sadness was all around. The sun felt guilty and did not dare to appear.

From all the blocks, people came to the block of the Jewish elder. People were lying in the bunk beds, stood in the aisles, pressed to each other and hung onto each other. Everyone who felt his Jewish heartbeat came. Even the block elders and the Kapos. They belonged to the elite. But now they stood among the ordinary prisoners. Fear befell them. Even the German block elders and Kapos, the horrible murderers became silent. They avoided passing the barracks. For some reason, today they became frightened of the Jews.

The Rabbi was chanting. He was a new arrival. Acquaintances had helped and supported him. So many Rabbis had perished. At least let one Rabbi survive.

Wrapped in the tallit, the Rabbi prayed the preliminary prayer before Kol Nidrei. Clear was his voice. We, the prisoners around him, froze. We felt that we were the sacrificial lambs who had put our bodies on the altar to be burned for the sanctification of G–d's name. Through the broken walls of the barracks, I looked out and saw the chimneys of the crematoriums from where smoke was mounting into the sad skies. I heard the sound of the Rabbi – not a sound that came from the heart but as if the heart itself had opened and cried: “And with the little blood and milk that is left in us we pray”. We stopped and repeated the same verse again. We emphasized the word: “little” and gathered repeating after him the two words: “our blood and milk”. And suddenly, someone yelled: “The blood and milk of our parents, our children and relatives”. Tears were dripping from everyone's face. The sobbing poured out like a river, even the stone–hearted could not resist crying anymore. I did not cry. I could not take my eyes off the smoke coming from the chimneys. I felt tiredness in my bones. In the barracks was an unbearable heat.

When the Rabbi began: “with the permission from above”, I was carried off into another world. It seemed to me that I was sitting in a catacomb in Spain and seeing the auto–da–fe, the horrible Torquemada, the wretched Jews who were burning for the sanctification of the holy Name and the smoke of the burned ascending into heavens. I heard the “Shema Israel” that the black wrapped souls took with them. I saw people clothed in black, masked and coming into the catacombs. “To pray with the sinners”, the Rabbi continued. The black–clothed people from my vision. I heard the Rabbi say: “From this Yom Kippur on”, and suddenly there was silence. A dead stillness reigned in the barracks. Nobody was praying. Nobody was crying anymore. As if all the people became speechless.

However, from the outside, frightening wailing was heard. On the road that runs alongside the barbed wires, women were being led to the ovens. The sounds of the truck engines overpowered the sound of the lamenting and naked women. Among the gathered here, there were many who had their dear ones

[Page 389]

among those women. Everyone was lying still as if they were trying to recognize a familiar voice. Through the open gate we saw how the victims stretched out their arms toward Heaven and pleaded for mercy. The screaming became louder. We were all in a state of shock. The Rabbi was the first to awake from the numbness that overtook everybody. He interrupted Kol Nidrey and began the prayer: “Unetanei Tokef Kedushat Hayom”. His voice was heard in the stillness of the barracks as if an echo was responding to the wailing of the women. His voice sounded clearly and when he reached the verse: “who shall perish by fire” – a lamentation came out of everyone's throat, repeating the Rabbi's words as if from the world beyond. “Who shall perish by fire” the Rabbi kept saying but his voice was drowned out as if the worshippers were trying to rescind the verdict of the tragic fire. But the engines did not stop humming as more and more victims were brought to the ovens.

“And who by fire?” The people did not stop screaming. The voices of the wretched integrated with the men's prayer. As if hypnotized, they repeatedly yelled: “who will perish by fire?” As if they wished that the fire should absorb them too. And suddenly, in the middle of the prayers, the sound of the shofar was heard. Someone was blowing the shofar. The shofar woke up the people as if from a dream. First silence overtook the barracks. I heard my heartbeat and soon everyone was crying. While the worshippers were crying, the shrieks of the naked women reached the heavens. The sound of the bells was heard signifying that we had to return to our barracks. We were hurrying not to be late. In the block where we prayed, near the stove which we turned into a pulpit, the Rabbi, the shepherd of the flock, lay dead, wrapped in his tallit. There he breathed his last breath.

The crematoriums, which were surrounded by a grove, were burning all night. The ovens were not big enough.

[Page 390]

My road of suffering

By Reuven Greenbaum

Being under the German rule in Strzyzow, I shared the suffering with my family and we were sent off to Rzeszow together with the rest of the Jews. In one of the many transports which were sent to Belzec were my parents. They were sent there to be annihilated. The moments of our separation will remain with me all my life, when my dear mother handed me her jewellery which she had inherited from my grandmother Golda. Among them was a long, golden chain with the watch which she had received on her wedding day and the Sabbath diadem studded with pearls and diamonds. Possibly, she had saved my life with this jewellery. It enabled me to buy bread in the different concentration camps. A message from my sister in Belzec was delivered to me by an S.S. man. I was grateful and rewarded him for it. How na´ve I was. I did not know that this was part of the Nazi scheme to calm down the relatives of the victims and cover up their evil doing.

Reuven Greenbaum

I was sent away from the Rzeszow ghetto before the Nazi finished their destruction there. First, I was sent to Bieszadka, from there to Pustkow. From Pustkow to Auschwitz near Gliwice, Grossrosen and finally to Matthausen, the worst of them all. Luckily, the camp was overfilled and they did not let us in. So I was sent to Limeritz. I finished my trail of suffering in Theresiendstadt where I met Elazar Loos. And there I was liberated.

Reuven Greenbaum

After liberation, I was sent to Buchenwald which became an American camp for the liberated. I was very young – a teenager and, therefore, I was allowed to settle in Switzerland because they had agreed to take in children. From there I immigrated to the United States where I live until this day.

This material is made available by JewishGen, Inc.

and the Yizkor Book Project for the purpose of

fulfilling our

mission of disseminating information about the Holocaust and

destroyed Jewish communities.

This material may not be copied,

sold or bartered without JewishGen, Inc.'s permission. Rights may be

reserved by the copyright holder.

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Strzyzow, Poland

Strzyzow, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Yizkor Book Director, Lance Ackerfeld

This web page created by Jason Hallgarten

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 09 Aug 2015 by JH