|

|

|

[Page 24]

Part I

A superficial observer might think that my story concerning the tragedy of the Slovak Jews and my personal sorrows comes a bit too late. This book will describe my own unbelievable experiences and my three years of suffering under the heel of the Nazis. I especially hope that my Jewish coreligionists will take heed of what I have recorded.

The book will also attempt to show that the travail of the Slovak Jews did not terminate with the downfall of Nazi empire. The five years which have passed since the end of hostilities seem to have shoveled the sand of times over the mass graves, ever the wounds. The beat of a new life can be heard over the dreadful past.

Many things changed since the gates of the concentration camps were swung open for their derelict inmates. Many a card appeared from under the table, many formerly hidden connections came to light. This book aims to give a warning, to forewarn forever human conscience, so that the criminal games of the Nazis and the Fascists will never be repeated. I also wish to remind humanity, as best as I can, not to forget the terrible and bloody legacy of the Second World War, and to implore mankind to stifle in their beginnings every hidden or open fraud of politics which might likely lead mankind once again into aberration and, perhaps, to an era of new Oswiecims, Majdaneks, Matthausens, Treblings, and Buchenwalds.

[Page 26]

The collective tragedy of the Slovak Jewry is marked by the terrifying figure of 100,000 Jewish dead. In the beginnings of these tragic events the territory of Slovakia comprised considerably less than it does today. At the outbreak of the war 89,000 Jews lived in Slovakia. OF this number 71,000 perished in the Nazi hell chambers. Numbered among them were not only the very aged, longing for eternal peace in the cemeteries of their forefathers, but numberless unborn children as well, men in their prime, women, scientists, workingmen, laborers, a professional people. Mine, yours, his and hers: fathers, mothers, sons and daughters, brothers and sisters, friends and strangers. Every one of the 108,000 murdered were loved by someone, esteemed by someone, somebody's acquaintance useful to one, irreplaceable to another, all personally dear. Every one of them in normal times would have been buried in decency, mourned by his relatives and friends, and be placed to eternal repose according to the customs of his faith. When we contemplate these cold statistics in the light of human feelings and sympathies, we see nothing but endless, innumerable rows of mourners whose sorrowful cries unceasingly reach the ear, nor can they be stilled.

These 100,000 dead do not represent merely a statistic, a number, a cipher. They are much more. They were mothers, children yet unborn, helpless grandfathers and grandmothers, flesh and blood, creatures endowed with senses and intelligence, hard working: full of zest to live, they were compelled to look upon the terrifying instruments of mass murder as witnesses on their road toward their ultimate extinction. No normal person can ever visualize the terror and the horrors these experienced. No work of art, no technical reproduction of the scene of their death will ever reproduce or re-tell the story of their sufferings.

No work of literature, no line of writing will ever recapture the pathos of the sentences written on scraps of stolen paper by mean of a tiny splinter of wood dipped in the blood of an unhealing wound. These words, arrested in limbo, frequently bore messages to addresses who too often met death as they received them.

[Page 27]

|

[Page 28]

The smuggled-out messages, by and large lost today, bear testimony to the greatest humiliation known to man. They carried words which the poets and dramatics never yet thought of placing in the mouth of heroes of the tragedies with such implacable force.

It suffices to cite a few of them, and mankind which will only reluctantly believe in them, will realize what it means when someone received a message from Lodz, Oswiecim or Buchenwald as for instance the message which brought to this writer this information from his brother:

“Tonight while I was out working, they took away my wife and my children. They also stole my shirt, trousers and shoes. I am hungry, naked and feel abandoned…Please, tell Clara that her father is dead. Tell his son Max, if he is still to be found at home, to say a prayer for him. He was hot last evening by a drunken guard…”

Or this message:

There was a transport leaving Oswiecim, not of the kind we knew before. When one is sent to such center, it means death.”

In these messages sorrow and death defile side by side with the instinct of self-preservation. This chronicle by an author mindful of the duty to caution mankind of these tragic happenings does not merely seek compassion of the world for the victims of Nazi barbarism. No amount of begging or dramatic appeals will ever bring the victims again to life. What is more important is for the world to realize that we must prevent the repetition of such barbarism and to see to it that those murdered multitudes will constantly be recalled to the conscience of the world, so that any attempt to restore Nazism or Fascism will be met by an impenetrable and resolute barrier.

This writing, then, is to be considered as a modest attempt to lace a spotlight on the events and happenings which led to horrible murders: the author will attempt to show who caused all these horrible acts be repeated, and what forces attempted to prevent the executive of these dreadful crimes.

[Page 29]

|

|

|

|

[Page 30]

One has to bear in mind, above all, that the tragedy of Slovakia's Jewry is not isolated fact. It cannot be separated from the over-all Nazi plans of conquest. The tragedy of Slovak Jews is an integral part of the tragedy of Jewish people the world over, a tragedy which was made possible by the tragedy of modern man led down the wrong path by the false prophets of Nazis and Fascism. The anti-Semites fury of the Nazis reached beyond national borders.

In the book of the tragedies of mankind crushed by two imperialistic wars the Jewish question represents but a single chapter. One hundred and eight thousand dead members of the Jewish community of Slovakia represent merely a fraction of the 57 million victims of the Second World War. Six million murdered Jews, representing one third of world's Jewry, makes only for one tenth of the entire bloody count of Nazi brutality and insanity.

The somber story of Nazi rule in Slovakia is particularly sorrowful since these crimes were perpetrated in a State which called itself Christian. The ruler's propaganda blared to the entire world that it was guided by the principles of love to one's neighbor, of respect toward God's command, of equality of men before their Creator. Germany's Nazis declared in unmistakable terms that they were engaged and would press the fight against Christianity, so that they did not, and never should be able to declare that they were guided by the principles of Christianity. Neither were many other countries where deportation of Jews took place ruled by regimes which advanced themselves as Christian. Almost everywhere the fate of the Jews was decided by the ill-will of the Nazi conqueror. Not one of the conquered countries took the initiative, but each, servile, executed step by step the Nazi command to achieve the mass murder of their Jewish population.

In so far as the citizenry and officials of these countries resisted those orders and attempted to prevent their execution or at least attempted to alleviate the misery of the condemned, can judgment be made of their character, conscience or lack of depravity.

[Page 31]

|

|

his body is dumped in one pile, ready for mass burial. Here you see a pile of bodies. Later they began to cremate bodies in order to save on labor |

After an inmate lost his life in a gas chamber, his body is dumped in one pile, ready for mass burial. Here you see a pile of bodies. Later they began to cremate bodies in order to save on labor.

[Page 32]

In attempting to weight the degree of guilt by association of the former pro-Nazi leaders of the Slovak State, one must bear in mind that this political formation appeared on the scene March 14th 1939 by the grace of Hitler, and brought to light the first of the non-occupied countries which consented to the practice of deporting Jews as early as 1942 at a time when no other of the Nazi satellites showed willingness to become accomplice to this horrible crime. In 1944 even they were practically overrun by the German armed forces. Rumania, Bulgaria and Hungary rejected Eichmann's proposal to deport Jews.

To so-called Christian regime of the Slovak State not only adhered to the scheme of Nazi crimes but – as it can be seen from the material contained herein – came out initiatively with the proposal of deport Jews. This at a time when Horthy, of Hungary, and Antonescu, of Rumania, still resisted Eichmann's insistent persuasions (notwithstanding that they did not because of any particular sympathy for the Jews but because of strong resistance among their own crowd against such plans).

It is difficult to understand how a regime, which talked so much about Christianity, could be the first one to join the Nazis in their anti-semitic fury, so that they outdid, in their hatred of Jews, even such people as Horthy and Antonescu. Was it perhaps because there was more of anti-Semitism in Slovakia? Or did the people force the government to deport Jews even at a price involving a tarnishing of the Christian conscience forever.

This question cannot be answered in the affirmative. The population of Slovakia, exposed to systematic propaganda in the press and radio, from speakers' platforms and in the electoral campaigns was not more anti-semitic than any other nation subjected to Nazi propaganda and the pressure of native Fascists. It is precisely the tragedy of Slovak Jews that it is not just nor right to say in this connection that there was a case of some unusually virulent intolerance among the population of Slovakia.

Going back in history, it suffices to recall the times when Czarist imperialism together with the landed gentry of the

[Page 33]

|

|

These had to be put in order by the old, remaining Jews. |

[Page 34]

Ukraine and Poland instigated throughout the Slavic world a series of unbridled programs. Did similar outbreak of unbridled passions occur in Slovakia at that time? Did we witness any occurrences similar to what happened in Ukraine, Galizia, Bessarabia or Bukovina?

All in all, no pogroms occurred in Slovakia, save for some sporadic disturbances which occurred during some of the election campaigns as the immediate aftermath of the First World War. These disturbances never were of any considerable proportions. Neither did the fable of ritual murders find as much fertile soil here as elsewhere. In so far as any anti-Semitic violence were noted they were always more ease of premeditated disturbances put up by ignorant elements swayed by vision of looting, food and drinks, than a cause of pure political hate.

It is a great misrepresentation reality for anyone to assert that the so-called Government of Bela Tuka reflected the desire of the majority when it entered into negotiations in 1941 with Himmler's henchmen concerning the so-called “liquidation of Jewish question” (read: liquidation of the Jews). Even though it may be said that at the time the rest of satellites shed away from Nazi bestiality, it cannot be said that Slovakia was infected by the anti-Semitic virus in a degree greater than any other European country. The action of Tuka's Government only meant that the Slovak people deprived of their rights were unable to give expression to their will. The people very often had to keep hidden their sympathy towards Jew if one did not wish to come into an open conflict with the authorities, the police, and the Hlinka Guards.

In this perspective, the tragedy of the Slovak Jews bares in its horrible details the dreadful guilt of the Government then in authority in Slovakia. It was this Government which used Slovakia, un-occupied as vet. into the network of Nazi crimes.

It was no lesser a Nazi than the so-called “Berater” (adviser) to the war time puppet Government in Slovakia. Dieter Wisliczeny, who wrote the following in his prison diary under date November 18, 1946: “It was in April 1942 that the Slovak Government offered to deport Jewish labor and, later on, their depend-

[Page 35]

|

|

|

[Page 36]

ents”. Said Wisliczeny was arrested after the liberation as a Nazi war-criminal, and subsequently condemned by the People's Court in Bratislava to be hanged.

The guilt of the so-called Slovak Government is awful to contemplate. It is difficult to describe the hypocrisy of this Government which while perpetrating these crimes, never ceased to assert that whatever was being done, it was compatible with Christian conscience. While the Jewish population of Slovakia was being bled white, hypocritical leaders of this so-called Christian Government talked of having taken good care of the deportees. These quislings of the Nazis talked of how well they had cared for the religious need of the deportees, and that they had respected the sanctity of family bonds. They bragged about having seen to it that families must not be separated. There is no greater example of pharisaism as those criminal rulers self-righteously asserting that they were genuinely worried as to whether the religious needs and rites of deportees would be properly attended to ad safeguarded.

This book cites only a few instances of the depravity of the human mind. It is almost impossible to visualize the perversity of perpetrators of these crimes and their accomplices in Slovakia.

[Page 37]

|

|

at Trebisovo (Slovakia), they also destroyed the synagogue and desecrated valuable religious objects and burned them |

[Page 38]

Slovakia had a particular status among Nazi satellites. The country was not occupied by Germans until 1944. For the local Government it was possible to appoint native citizens to key positions in the governmental and economic life as well. The Nazis were fully preoccupied by war and by millions of starving Jewish victims of their barbarism. It was quite likely that the Nazis would not have commenced any particular campaign against the Jews in Slovakia except in the event of an uprising in Slovakia. The Slovak people actually did rise against the Nazis, in 1945. The so-called “final liquidation” of Slovak Jews would not have occurred in Slovakia had it not been initiated by native quislings. Were the Nazis to meet any resistance on the part of Slovak authorities, however weak., it might be that it would have been possible to postpone the executive of the Nazi plan as to the Jews until later, at least until then when the entire country was occupied by the Nazis as a result of Slovak uprising which was crushed in 1945.

The so-called Slovak Government is responsible, however, for the 60,000 Jewish persons who were deported from Slovakia to Nazi death camps in 1942. Conscience stricken, the puppet Government of Slovakia self-righteously declared that it had at least saved those Jews which had been baptized and accepted in the Christian faith some time earlier. The masters of Slovakia's destiny used these exceptions as proof positive of their mercy and Christian understanding. In reality, they only persevered in their criminal belief that it was ethical to discriminate still further against people denounced because of their race. They considered difference in religion as sufficient justification for mass murder of the members of the religious minority.

In order to rationalize their actions, these self-righteous leaders of Slovakia asserted later on that at the time of the deportations they did not know the fate which awaited the deportees. They further claimed that they, in the fall of 1942, ordered the deportations to be discontinued, and that it was only then, in the last months of 1942, that they learned the truth about Nazi concentration camps.

[Page 39]

| The “King of the Jews” of Slovakia who decided the fate of Jews and made selections as to who is to go to concentration camps. The result of his work was the disappearance of 68,000 Jews of Slovakia. Here you see him; who he is making excuses for his act before the Court. But he was found guilty and sentenced to death by hanging in Bratislava. |

|

|

| Dr. Anton Vasek |

[Page 40]

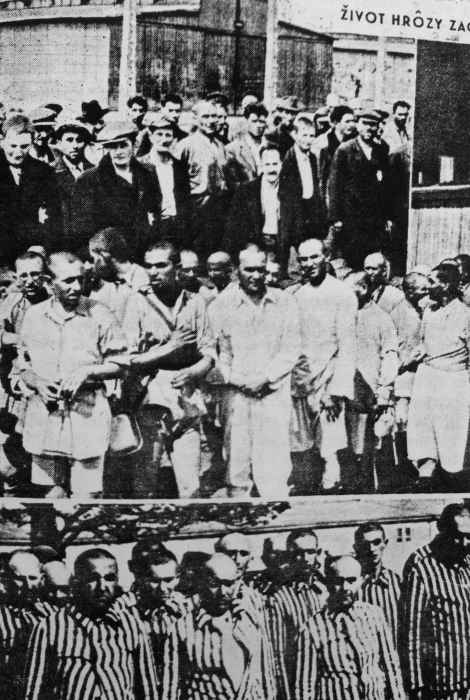

The pictures published in this book speak for themselves. By taking advantage of several years old anti-semitic tradition the regime participated fully in the anti-semitic crusade. The procedure was exactly the same as in Nazi-occupied countries. First, a whipped-up anti-semitic propaganda from the outside, then the piratical legislation which deprived the victims of the fruit of their labors and, finally, the deportation into slave labor camps, and murder.

If some of the perpetrators and accomplices of these crimes assert that they did not know what would be the ultimate fate of the Slovak Jewry, they are not speaking the truth. They only aim to deceive the world by claiming today that they would never have given consent to this murder, although they openly admit that they willingly participated in the persecution of the Jews; that they approved of looting, enslavement and deportation. Their purpose of deporting Jews was that the Jews should never return to Slovakia. They realized only too well that the bedraggled mass of Jewish deportees would mean a heavy yoke even for the Nazi economy and that the Nazis would seek to rid themselves of the deportees. Gas chambers were the logical conclusion of this policy which was strictly adhered to by the so-called government of Slovakia.

The death of six million Jews and more than fifty million other victims of war is the logical consequence of anti-semitic racism, just as racism, Nazism and Fascism is the logical consequence of imperialism.

This tragedy of the Jews did not begin with the era of Nazism nor with the Fascist march on Rome. Neither will it end unless such order is instituted in the world which will not permit Governments and rulers to proclaim that they are protecting civilization and Christianity while they perpetrate the most horrible crimes against humanity. It is self-evident that while the Tiso-Tuka Government in Slovakia had one hand on the Bible, it gave blessing, with the other hand, to those who were murdering Jews by hundreds of thousands.

Part II

My death or life struggle with the Nazis

On March 15, 1939 while listening to the radio, I learned that it had been decided at Hitler's Headquarters to press for the speedy passage of drastic legislation against the Jews of Slovakia. I had previously made my mind to consider such news merely as a part of the campaign of intimation, and I quietly carried on with my daily routine.

It was not until later, on December 10, 1940, that local Fascist papers came out with screaming headlines such as this: “The Jew wished our death, let's throw him out of Slovakia.”

On July 15, 1941, the Ministry of Interior published the infamous degree 7201/II/4 – 1941 which reads as follows:

“In accordance with Paragraph 2 of the Law 190/1939 it is prohibited for all Jews and persons equal status, in the public interest, to

It is mutually prohibited to maintain any social contacts between Jews and Aryans one side, and between Aryans and Jews on the other side.

The term “social contacts” is to be interpreted as meaning not only contact at homes, but any contact on the streets, public

[Page 42]

places and the like. The prohibition of social contacts between Jews and Aryans and vice-versa is to be extended throughout the entire territory of Slovakia. Overstepping of this Law is subject to prosecutions, and the offenders will be sentenced to a term of six months in prison.”

On September 10, 1941 the puppet Slovak Government passed a law as to who was to be considered a Jew.

Six days later the Premier issued an order to the Central Economic Office ordering the latter to do its utmost in carrying out the special ruling providing for the exclusion of Jews from the economic life of the country, and for the transfer of Jewish properties to Aryans.

The month of March 1942 approached. The radio brought an announcement ordering all Jews to report to the draft boards. This was, of course, a trick. The Government radio merely tried to conceal the fact that the Jews were to be drafted for slave labor camps. Prison terms of six months were announced for those who failed to heed the order.

Almost every Jew, not wishing to antagonize the Fascist authorities any more, reported quietly to the draft board.

Previously rumors had it that the Jews would be deported to Poland. Many did not believe that deportations to Poland would take place. They preferred to believe that the Jews would be kept in labor camps in Slovakia itself.

My brothers, like the rest of Jewish young men in our town, reported to the draft board. I however, the youngest in our family did not so report. I did not want the Fascists to have any records as to my person. I knew that all this was a mere smokescreen and that the Fascists merely attempted to get a grip on the Jews the easy way. Many young Jews fell for this and wee subsequently deported to labor camps in Poland.

The month of March 1942 passed quietly, and Nazi propaganda relented a bit. The entire situation seemed very suspicious to me. I tried to explain to my family that something was afoot, and asked everyone not to be deceived by this apparent lack of wild

[Page 43]

propaganda in the papers. The war raged in full swing. Hitler advanced and his armies approached Stalingrad. The warm, tepid April days of 1942 arrived. The remaining Jewish population of Slovakia became panicky. Rumors circulated among Jews, and non-Jews, as well, that the Nazis would draft Jewish boys and girls. The girls were to be sent to the front, for the brothels, the boys were to be sent to the task of rebuilding of roads, bridges and houses. Every father and mother not realizing that they, too, would meet their end in tragic death at the hands of the Nazis attempted to save their children from deportation. The only means of escape was to flee to Hungary. Some of those who lived in border regions succeeded in their attempt. Some went into hiding. It was not too easy to hide, for the Fascists installed guards and informers everywhere. The only relatively safe hiding place was the mountains. But then it was necessary to build caves and accumulate enough food and clothing for the winter. This was not easy to accomplish.

Although I was in hiding most of this time, I also wanted to save my sister, who, unmarried was subject to draft into the labor camps. And so I took her to another sister who was married, and who lived some 150 miles away from our family. I secured the services of a dependable taxi driver who took us, at midnight, to our sister. We were very lucky to evade all the roadblocks and control stations. When we arrived at our sister's house, everyone inside was asleep. We knocked on the door and windows until finally our brother-in-law opened the door. We awoke our sister. Not knowing what was going on she became so frightened that she fainted. I left my unmarried sister there and returned home since our parents were anxious to know how we fared. I came home at dawn. Our parents were still awake.

On April 15, 1942 at 9 a.m. the so-called Hlinka Guards appeared in the streets, taking boys and girls into custody. People cried and shouted. One could see Jewish young men being led away by armed guards. Some youngsters escaped. Fully ninety percent, however, were taken away. The deportees were permitted to take with them some forty pounds of clothing and food for three days.

[Page 44]

The guards searched Jewish homes until finally they came to us too. They asked for me and my sister. They turned the house upside down, looking into every corner while menacing our parents and hurled all sorts of insults on them. When our parents declared that we were gone, they were told that they would be shot. Of course our parents did not reveal that they knew of our whereabouts. The guards finally left and let our parents alone.

In the evening, the guards forced the assembled deportees into a cattle train and subsequently into one of three deportation centers in Slovakia whence the Jews were transported to Poland.

During all this time I was not too much concerned about where to hide. I told myself that either I would come out of this alive or they would not take me alive. I never stayed in one place for more than a day. I slept in a different place each night.

Of course, I could not carry on like this for a long time, and so I decided with my nephew who likewise stayed with me all this time, to make our hiding place in a big stack of straw on the outskirts of our town. We had a supply of food from our parents' home: dried fruits, canned goods and bread. However it was impossible to store supplies because the heat in the stack became unbearable and the food spoiled easily. Local police informers soon learned what was going on. They again searched my parents' home.

One day, as I came home for supplies once more, I didn't even realize that the guards were on my trail until I saw them coming into the courtyard and entering into the house. I quickly jumped out of the window and ran away through the garden not however without being shot at by the guards who stopped me. They did not hit me though and I escaped empty-handed.

Two days passed. My parents were unable to bring any food to a place previously agreed upon and I decided to try again and see whether I could get home anyway. As soon as I entered I was very surprised to find my sister there, the one which we took away to relative safety three weeks previously. I reprimanded her sharply for having come back. Tired to death, I decided, nevertheless, to spend the night at home.

[Page 45]

My sister was very tired too, and frightened. She explained that she could not possibly stay at our sister's any longer, since her hiding place became known to the police. She declared that she had had enough of this misery, and that she would not budge from our home. She also said that sooner or later the Nazis would deport every Jewish person, and that she intended to stay together with our parents.

Nothing happened during the night, and it was impossible to leave the house during daylight. The next day ended tragically for our family; for the guards surprised us once more. I escaped the same way as before but returned soon thereafter to observe from a safe distance what was going on. My sister, Frieda was her name, first escaped through the back door and hid behind the stable. The Nazi guards, who originally came to get me, were very surprised to find my sister in her hiding place, and without permitting her to say Good-bye to our parents they took her into custody at once; they led her out on the street, stopped a passing automobile, pushed her into the car and ordered the driver of the vehicle to take her to a city prison in Trebisov.

Later on I learned that they took my sister, with30 other prisoners, to a concentration camp called Patronka, located near Bratislava. From this camp my sister was transferred, together with 1060 other victims, to the infamous Oswiencim concentration camp in Poland.

As I later learned they crammed 106 people into a boxcar. I also learned that my brother Alexander was caught in the same raid. He was then transported from Trebisov along with 120 persons of Jewish faith to an unknown destruction.

At about the same time another incident occurred in the vicinity of a nearby town called Humenne. There, in the woods, someone killed a gendarme. The Nazis of course claimed that this was the work of Jews. The purpose of spreading such rumors was to make non-Jewish angry and prejudiced, and to facilitate the mass-arrest of the Jewish population. Some 150 persons were arrested in this connection. The Nazi authorities let out rumors that every

[Page 46]

second person of those arrested would be shot unless the perpetrator or perpetrators of the murder of the gendarme was found. Finally, after two weeks of detention, the arrested were released since the investigation disclosed that the culprit was not a Jew.

[Page 47]

Soon the tragic, incredible day May 2, 1942 arrived. It was the day of the Sabbath. The entire Jewish community assembled in the synagogue. A notice was posted on the church wall. The notice was undated, and did not stipulate whether it concerned the young or the old people. It merely stated that every deportee was to carry with him, or her, up to forty pounds of clothing and food. The older folks simply did not believe that they too were to be deported, since the pro-Nazi Government of Tiso and Tuka bellowed time and again that whoever cared to listen that their Government was fighting for Christianity and humanity.

No sooner had we left the church when we saw on the street some hitherto unseen Nazi uniforms. We approached the chairman of the Jewish community and asked him what was this all about. He replied that he feared the worst, that all of us would be deported. I asked him whether we should flee, to which he replied in the negative, adding that according to authorities we were all to remain together, that we would be taken to Poland and that our families would not be split up.

That very same afternoon, at two o'clock, a whole group of Nazi guards were seen searching Jewish houses. Their first victim was a man named Jozef Weinstein. They were leading him through streets. He had a small trunk in his hand. On the way to military barracks the guard beat him. It was one of the local Nazi police who acted most savagely. He was in a rage because Weinstein a few weeks earlier had refused to let him have his textile store.

From a safe distance I observed that Weinstein's house was sealed. A few minutes later I saw the Nazis leading other Jews away.

Afterwards, I returned home where the rest of our family was gathered. We feverishly discussed the situation. Everyone was crying. My brother Arnold declared that he would go along with the rest of the deportees since he believed that he would thus help our parents. He believed the Nazi Government would real-

[Page 48]

ly permit the families to stay together. In this he repeated what the chairman of the Jewish community said shortly before. I, however, did not believe the Nazis in the least. I told my family what I saw on the streets and urged everyone to go away and hide. My father, seventy year old and gravely ill, was simply unable to realize any more what he was doing. Laying in bed, he declared that, perhaps they would not dare to take him away in his condition. I decided then that I would not go with the rest of the deportees, and readied myself hastily for a hasty departure. I put some bread into a crude bag, went out a tucked the bag safely in the stack of straw, and remained outside. In the meantime I observed carefully what was going on. I was especially careful not to let myself be seen. I spent the rest of the day in the garden. My head was ready to burst from sorrow and anxiety.

In the meantime the rest of our family made preparations for the inevitable. At six o'clock the guards came. They entered our house and left within a half-hour. From where I stood I could see my brothers and parents being led away. The Nazis put the house under seal. All my family was standing in the courtyard. My late mother went for the last time to the stables where we used to keep three cows. She gave some fodder to the animals. Then she rejoined the rest of the family who were in the courtyard watched over by armed guards.

Then the guards took my parents and the rest of the family away to the military barracks. They did not show the slightest consideration to my parents who were old and ill.

That day I became an orphan.

I remained in hiding in the garden. My heart was heavy from sorrow. Disturbed in the extreme I simply did not know where to turn. Should I give myself up? What was now that I was to become, left entirely on my own?

It was impossible to stay in our garden any longer. It was too easy for anyone to detect my presence, and so I left the garden furtively only to return that same night at about ten o'clock.

[Page 49]

Everything was quiet around the house. I broke the seal on the door and stepped in. I found my overcoat and was ready to leave again when our tenant, to whom we leased one storeroom, realized that someone was inside the house. --- Who is it? He asked. I changed my voice and said just one word: Gendarmes. There was no further exchange between us and everything went silent. I took some more clothing from my room and left quietly.

At midnight I set out for my former hiding place in the straw stack. When I reached the place I found my nephew who remained hiding in the stack all this time.

He was very impatient to learn what happened. No sooner had I told him what occurred when he fainted. He came to however, and I pushed him out of the stack to breathe some fresh air. At three o'clock in the morning he even went to the shore of Ondava River to get fresh water for us. We were exhausted and desperate, for it was none too wise to stay in the stack any longer. An escape to Hungary, which we discussed thoroughly, seemed too problematic since it involved the added risk of falling into the hands of the border patrols. The surveillance on the borders was growing better every day, and so on the evening of the next day we headed for town.

The purpose was to get our own alcohol heater. When we came to the town we had a sudden change of mind and we decided to try spending the night in our family home. The night was very dark. We approached our house. Everything was silent but for the barking of a dog. Nothing suspicious in the courtyard. We knew that the doors were locked and sealed and that the gendarmes were supposed to stand guard over confiscated Jewish houses. But we knew also that this surveillance was far from perfect or efficient. The gendarmes saw to it that there would be enough sloppiness as to make it possible for the gendarmes themselves to rob these houses at night. In addition, the recently promulgated decree ordering the entire population to stay away from the streets after 8 p.m. under the penalty of loot sequestrated Jewish homes undetected.

We made our way into our house: I pried the seal open again, entered my own room and searched for the heater. All of a sud-

[Page 50]

den I heard someone entering the front room. Sure enough, they were gendarmes. Two of them. They entered through the window and hastily whispered to each other. In a split of a second I ducked under the bed, breathless. I heard them whispering: “Let's get it quick!”

First they took the candlesticks, then my sister's coat and lingerie, and a lot of other things. They piled everything into two trunks and were ready to leave. Shaky and holding my breath, I thought this was the end of me. But they left without noticing my presence or my nephew who stayed outside on the lookout.

I learned afterwards that in the afternoon of the very same day all Jews were taken away from Trebisov's military garrison and shipped in boxcars to Zilina, and from there to Poland. Part of them was sent to Majdenek while others were shipped to Lublin. None but four families were spared the ordeal. They were so-called Presidential exceptions, the term used for those who were spared on explicit orders of Tiso, the President of the Republic. In this particular case all four were families of dentists.

The clandestine raid of the gendarmes on our house caused us to change our minds again. It was obvious that we could not have waited in the house. We went back to our straw stack, taking the heater with us.

We remained there, inside the stack, for two crucial weeks. The heat inside was unbearable. During the day it was impossible to go out hiding. At night we crawled out to get fresh air and replenish our supply of water. The heat inside the straw stack was so intense that the water warmed up to point where it was almost possible to cook dough in it.

Then the day May 16, 1942 arrived. From our hiding we saw a peasant cart approaching. As it developed, a neighborhood petty farmer came, with three other men to pick up some straw. The stack did not belong to him. He merely borrowed a load of straw from the owner who did not have the slightest idea about us hiding in his straw stack. The stack itself was located some six miles from the town of Trebisov.

[Page 51]

Neither did the Ruthenian farmer who came to pick up the straw know about us being inside the stack. As he searched for a better quality straw and started digging deeper he spotter our hiding place, and started to investigate. I stuck my head out. Taken aback, he asked what we were doing there. I explained why we were there to which they all replied that, in truth, they knew we were hiding in the stack. We then gave each man five hundred crowns (worth then about twenty-five dollars), and begged them not to betray us to the authorities.

They promised that they would not say a word to anyone, accept the money, and assured us that we would not have to worry about it anymore. Then they piled the vehicle high with straw and left.

We went back to our hole, nervous and frankly worried as to whether those people could be trusted. We decided right then that we must flee that evening. I actually wanted to leave immediately but was unable to move so tired and exhausted was I. I dozed off for a spell while my nephew was trying to read a book in the twilight.

At six o'clock that same evening I suddenly felt that someone on the outside was working feverishly, making his way through the mass of straw to our hiding place.

In a moment we saw men, armed with pitchforks and guns. They immediately ordered us to come out, hands up, and to hand them over our money. They brought two more men with them, all of them from Trebisov. As I learned much later, their names were as follows: Juraj Rusnak, Michal Tudna, Geyza Stanislavsky, Ladislav Hurcik, and few others.

We did not see at once that they were six in number. Two men were hiding behind the stack. As they shouted to us, I quickly grabbed one man, wrestled the pitchfork away from him, hit him hard and started to run away. The two other men, who were hiding all this time behind the straw stack, run after me, firing from their pistols. Fortunately they missed me, and I out-distanced them rapidly. I stopped running, wondering what was to become of the young boy who was with me. We agreed previous-

[Page 52]

ly that in the event one of us was captured, the other must give himself up, so that we would be together, come what may. And so I decided to walk back to the straw stack.

As I approached I saw that they had disrobed my nephew completely, looking for money. Of course they did not find anything on him, since we did not have any money with us at all after we gave them previously all we had. The man I hit earlier in the scuffle jumped at once to me and hit me with the pitchfork so hard that I fainted.

They disrobed me too, completely. They did not find any money on me. They then ordered us to come along with them to the town. On the way we begged them to give us a drink of water. They told us scornfully that we will no longer need any water, and that shall not live long anyway.

However, one of these Nazi thieves did not give up trying to extort money from us by promising us that he would let us go if we could produce a substantial amount of money in cash.

I asked how much they would want, and he said twenty thousand crowns. I told him that I did not have any money on me, but that, perhaps, I would be able to raise some cash in town.

My foremost thought was to escape, although I realized that this was very difficult on account of my young nephew. There was nothing left for me but to continue bartering with my captors.

I promised that I would produce five thousand crowns, but they would not listen to anything else but the full amount demanded.

It should be pointed out that for this amount it was possible to build, at that time, a new solid one-family house.

I kept pleading with them and promised them that I would try to raise 5000 crowns among my acquaintances in Trebisov.

Two of the gangsters, Juraj Rusnak and Michael Trudna, who seemed to be the leaders, would not hear at all of my offer. As we were nearing the town, I agreed, in desperation, to what

[Page 53]

they demanded. I asked that three of them stay with my nephew while I was to go with Rusnak and Tudna to town.

We came into a house of one of my acquaintances, a liberal-minded farmer's family, where I previously deposited some money for safekeeping in those troubled times.

I explained what happened and what we came for. The farmer asked first what happened to my nephew, and advised me not to give anything to those gangsters; he pointed out, in the presence of my captors, that the situation on the fronts was worsening for the Germans, and that our suffering might soon end.

When my captors, small-time Nazi thieves and profiteers, heard what the farmer so outspokenly said, they did not want to stay in the house any longer. The farmer gave them the money. I asked him whether he would be so kind as to go along with my captors and see that my nephew was released. My captors did not want to hear about this and replied that they would release us both as soon as we reach the place where my nephew and his three captors were.

While on our way back the two leaders of the gang asked me not to tell the rest of the gang that they had received all of the twenty thousand demanded. They enjoined me to say that I gave them only 15,000 crowns. I agreed to this.

When we came to the appointed place, I asked them to release my nephew at once, and to let us go. Instead of letting us go they grabbed us by our hands, and said: You gave us the money, but we shall not release you. We shall turn you over to the gendarmes. You will then be sent to Poland, and should you come back, we shall give you back your money. We advise you not to brag about having given us any money. Otherwise we shall report this to the Hlinka Guards and they will confiscate all your property. We also would denounce your farmer friend, and tell the authorities that you are collaborating with the anti-Nazi underground.

Not wishing to endanger my farmer friend, I kept silent. They took us to police headquarters.

[Page 54]

In the morning we were called for interrogation. We explained what happened. The police asked us whether we had given any money to our captors. I said that we did not. Then the police left us alone. We were incarcerated there three weeks, until enough prisoners were gathered to be sent, in a group of 100 persons, to a concentration camp.

While imprisoned in the police station I met a charwoman I knew. She was employed by the police to bring food to the prisoners. I implored her to bring me a file, or to put a file into a loaf of bread, so that I could escape by sawing off the prison's bars. She replied that she couldn't possibly do so, since it would have been easy to ascertain who had helped me. So I dropped the whole idea of escaping from the prison and I decided to wait until we were on the train on our way to the concentration camp.

On May 28, 1942 they sent out a big transport from our prison. I was in that transport. We were about 106 in number. Twenty gendarmes were assigned to guard us.

While in prison I made acquaintance with a young man, and we decided to escape together. We were at the railroad station. In the crowd I spotted the wife of a farmer I knew. She was on her way to market with a basket of eggs. I bought about a hundred eggs from her and a loaf of bread.

We boarded the train. The gendarmes were with us and watched us carefully. When we approached the main station in the town of Kosice, I found myself a place near the window. As we came closer I started throwing eggs into the crowd. People thought I was throwing hand grenades on them, or something. Everybody started to run. In the ensuing confusion I went to a washroom in the back of the car, and jumped out from the window.

I landed squarely and found that I was in a patch of cultivated land. I remained there for about fifteen minutes, thinking that I had broken my leg. Then I pulled myself together and set out for town.

I wandered around the town for about two days. Then the

[Page 55]

police caught up with me. They arrested me again and sent me to a frontier town where they turned me over to a border patrol. Two hours later, I was a free man again. I escaped.

I set out for the town of Presov. There I met a few Jewish families and acquaintances. They, too, were to report for deportation. So I left in a hurry.

Within an hour after I left Presov the gendarmes and the police were on my trail again. I set out at once for the town of Spiska Nova Ves. Again, the police surprised me on my way, and asked for my papers. Not having any, I was re-arrested.

My story was checked and I was sent again to Zilina where I found the deportees with whom I was originally shipped from Trebisov. The police investigated my case thoroughly, and bet me. A police inspector named Vaska was especially brutal during this investigation. He met his death after the war having been condemned by a Peoples' Court to be handed for war crimes.

They kept us all in the Zilina camp for a couple of days, waiting until sufficient number of prisoners was gathered to make a convoy. We were herded inside barbed wire enclosure and guarded by a special detachment of the Hlinka Guard in black uniforms.

For supper they used to give us raw sauerkraut, but nothing else. In the morning, a cup of lukewarm ersatz “coffee”.

I kept thinking of the camp in Poland. What would they be like, comparing the treatment we were getting in our own country.

The local press of course tried to paint a rosy picture as to the situation in Polish camps. Imagine, they, the imprisoned Jews, even enjoy some kind of autonomy inside these fine camps!

I could picture the kind of “autonomy” the Jews presumably “enjoyed” in Polish camps. It sufficed to observe what was going on in our own camp in Zilina.

When a transport came the old and ill men and women were thrown out of the boxcars as that they were animals. Many broke

[Page 56]

their legs or ribs. These unfortunate were then put on stretchers. Red Cross people took them to an infirmary. A few days later the guards kicked them out of the infirmary, fever or no fever.

Every inmate in the camp received a serial number. I noticed that some prisoners carried special white armbands. They were the orderlies. Usually, they were the last ones to be shipped to a death camp. I tried to get possession of such an armband.

One morning while I was arguing with one of the orderlies, a Nazi guard came by. He heard me telling the orderly that I felt ill and was unable to work. The guard immediately took my number down and ordered me to report to the office at noon.

I knew it means a severe beating for me. By sheer luck, I had two serial numbers with me. One belonged to a woman inmate. When I did not report as ordered, the guard set out looking for the holder of the number. He finally learned that he had been fooled and searched for me everywhere.

In the meantime I remained in hiding. I told my fellow prisoners that I intended to escape that very same night. The cautioned me against such action, and asserted that I would be shot while attempting to escape. Not one attempt to escape from this camp had ever met with success they told me.

I tried to induce another nephew of mine, who was with me in the camp, to try to escape with me. He refused.

In desperation, I remained in the camp for two more days.

On the eve of another big convoy to Poland, I escaped, not without being shot at by the guards. They missed me. A few moments after I was in town, Nazi guards were everywhere asking for identification papers. I soon reached the railroad station. I turned around, stepped casually forward along the rails, and posted myself at a safe distance, on the outside of the track, waiting for the train to move.

Eluding the guards and the crowds I jumped aboard while the train was gathering speed.

For a couple of tense moments I tried to orientate myself.

[Page 57]

Then, finding that there were no policemen or gendarmes on the train, I fell asleep.

After half way between Zilina and Kosice someone waked me. It was a gendarme. He asked me for my identification papers. I pretended that I was very sleepy and showed him an old social security card which stated that I was working on the railroad. Casually, I explained that I was going home from work and asked him not to bother me. He let it go at that.

Finally I reached the town of Hanusovce, near Kosice. I stayed there a week in hiding, until hey again caught me.

I experienced the same old routine. Only this time I did not reveal my real name. Back to Zilina again.

By pure chance there was no one in the record room when the gendarmes brought me into camp, but an old inmate, acquaintance of mine. I gave him a false name.

The very next day I was put on a train, with hundreds of other prisoners. Destination: Poland: my hope: a smuggled-in knife.

Each car was jammed to capacity. People began to suffocate from lack of air.

As the train approached the border between Slovakia and Poland, I finally succeeded in trying open a window.

Without losing any time I jumped out from the speeding train. A few others followed me, until the guards became aware of what was going on. They fired from their pistols, but did not order the train be stopped.

I remained in hiding in a field for a couple of hours. In the evening I set out by foot for my native town.

After several days of tribulations, I finally reached the town of Hanusovec, a distance of several miles from my hometown. I stayed there for two weeks.

Bitter experience and past sufferings taught me to try a new

[Page 58]

angle. From Hanusovce, I sent a messenger to my hometown Trebisov, requesting a member of a respected Christian family from Trebisov to come to see me. The man came. He was very surprised indeed, since he was led to believe that I was in Poland for many months already.

I asked the man whether he would be kind enough to institute a procedure whereby his family would be allowed to take over the possession of our house. It was a difficult and lengthy procedure but finally he succeeded in convincing the authorities of his good faith.

As soon as they let me know that they had moved into our house and that they made arrangements for me to hide inside the house, I moved in too. We dug a hole under the table, put a carpet over it and camouflaged everything very expertly.

I remained there for many months, and came out only at night since the gendarmes came searching for me on several occasions. As a matter of fact, they kept searching for me constantly for about a month. Then they gave up.

[Page 59]

It was at that time I found out more about the fate of those Jews who were deported to Poland.

I found out especially that my parents and brothers-in-law were led to believe that I was shot during one of my attempts to escape from a deportation train.

I sent them a letter under an assumed name through the Jewish agency in Bratislava which was still operating at that time. I also succeeded in forwarding five hundred crowns to my parents.

The receipt of said money was acknowledged in my father's own handwriting. This was to be the last letter I received from my parents before they died. They wrote:

“Dear son, the reading of your letter meant a new lease on life for us. Send us some old things, but no money. May God protect you wherever you are. Gruenfeld and Katz died from illness.

[Page 60]

In September 1942 news leaked from Poland that the Nazis began to use gas chambers for the purpose of murdering older inmates of concentration camps. In October of the same year, my parents succumbed to this ordeal.

The year of 1942 was a tragic year not only for myself but for all Jewish people in Slovakia.

Hitler was at the gates of Stalingrad. It was then that I began to think of suicide since I thought I was not able to endure this trial any longer.

Some people were saying that the war might last for at least four more years. The farmer's family with which I lived in our house and was taking care of me all this time tried to convince me that it was imperative for me to hold out a bit longer, and assured me that the war would soon end. They undoubtedly were in fear that I might be discovered whether dead or alive and that they would be punished by ten years of imprisonment for hiding a Jewish person in their household.

During the day they stayed out working in the fields, and in the evenings they gave me food. And so I remained in hiding there from June 1942 to December 6, 1944, the day of liberation of my hometown by the Russians.

[Page 61]

Throughout all this period of two and a half years of hiding I had never seen the sun once. I felt ill and discouraged until the time when the Nazis took their beating at Stalingrad in the Winter of 1943. I read the accounts, however scared, of what happened on the fronts, and I made my mind that I must hold out, although I was very ill and ate very little. I was often desperate reading of Hitler's boasts of some new arms which would win the war for him.

However, in the first days of June 1944, I heard something about the partisan movement in Slovakia against the Nazis, I knew the people of our town and was informed as to their opinions about the war and their attitude in political matters. It was during this period that I sent several letters using assumed names, to the most rabid of local pro-Nazis. The purpose of these letters was to deter them from any possible further action against the partisans and the democrats in general.

It was also at this time that I got in direct touch with the anti-Nazis partisans themselves through the intermediary of a Jewish doctor named Gyarfas, incidentally the only Jewish doctor who was permitted to continue practice in my hometown (Trebisov).

A partisan liaison contacted him, and through Dr. Gyarfas I, too, gave some money to the partisans.

Later on, this same liaison man came to see me in my hiding place, on information given to him by Dr. Gyarfas. It wasn't until then that I found out that the liaison man was no one else but my former schoolmate named Deutch. We had not seen each other for over six years.

This man's job was to seek contacts with those officials of the regime who would be willing to provide the partisans with false identity cards. To this effect, Deutch and I contacted another of my former schoolmates, a man named Sokolov.

I had lost track of Sokolov since we left school and I was not sure at all as to his political convictions. When he saw me at

[Page 62]

night he became very frightened since he believed I was long dead. Nonetheless, he promised to co-operate with us, however it was necessary to threaten him with reprisals in case of non-cooperation.

This man, to our great satisfaction and astonishment, brought us the very next night ten identity cards, blank ones bearing all necessary seals. Deutch then went away and I took over the leadership of the partisan movement in the vicinity of my hometown.

Sometime later we joined another group of partisans, and after two weeks we took to the mountains where we joined a large group known under the name of Tchapayev partisan group. We engaged the Germans in fight several times, blowing up bridges and holding up Nazi transports.

On December 4, 1944 the oncoming Russian armies liberated our district and I then enlisted in the regular Czechoslovak Army where I served until the end of the war.

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

The Tragedy of Slovak Jewry in Slovakia

The Tragedy of Slovak Jewry in Slovakia

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 12 Oct 2013 by LA