|

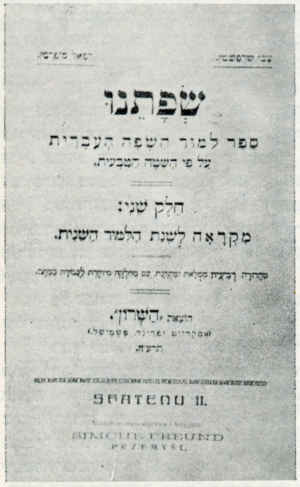

The title page of Sfateinu, a textbook for the study of the Hebrew language, in the natural style. Published by Simcha Freund in Przemyśl.

|

[Page 81]

by D. N.

Translated by Jerrold Landau

The constitutional era that began in 1868 did not precipitate any immediate change in the order of communal government of Austrian Jewry, including Galicia. The Austrian laws regarding “The Israelite Religious Communities” that appeared in 1890, delineating bounds of operation and granting the authority to impose taxes and fees in return for services only, did not permit them many tasks. It only granted religious autonomy only on a local basis, and not for the entire country or specific provinces. This autonomy did not have governing bodies of the second or third level. The communities remained disconnected. The right of voting for the communal body was only granted to those communal members who paid the specified level of tax for religious needs. The number of voters was small, as is shown by the example of Przemyśl in the latter years, before the outbreak of the First World War (1907-1913). According to the tablets of “The Austrian Jewish Registry”, we can determine that approximately 18,000 people lived in the community (including residents of the nearby towns), out of which there were 1,200 taxpayers. That is less than 7% of the general Jewish population, including children.[i]

Since the communal ledgers have been lost, we are unable obtain information on the communal governing institutions prior to the new law. We must suffice ourselves with fragments of information based on popular tradition. Dr. Bloch, a member of our editorial committee, recalls that his grandmother's father Reb Matityahu Brodheim, the 'regirer' (ruler) in Przemyśl during the time of Franz Josef, was among the notables of the city who were present at the reception for the Kaiser when he visited the city. He appeared before the Kaiser who asked him a typical question under such circumstances, and received an answer not in German, but rather in popular Polish. The elders of Przemyśl who are still alive still recall the elder Reb Yehoshua Steuer, who was the final “regirer” (ruler) of the community. He was an honorable man, apparently wealthy. The lawyer Dr. P. Gottlieb, a native of Przemyśl who died a few years ago in Israel, told us that in the year 1886, when he was a first year student in the gymnasium, he had a friend in his class whose father, Dr. Baumfeld, a lawyer in Przemyśl was the local “prezes” (chairman) of the “Israelite Religious Community”. Since by 1886 there was no such community in existence, and no “prezes” of the community, our informer erred either about the position of Dr. Baumfeld or about the year in which he performed his role, despite the fact that he had a good memory.

We have information about the community council and the head of the community from approximately 1893. The Gaon Rabbi Yitzchak Schmelkes was then about to leave Przemyśl in order to accept the rabbinical seat of Lvov, and he advised the community of Przemyśl to summon a rabbinical court from another city in order to make a binding decision about the “battle of the cantors” that was transpiring then (between the young Strucki and Schechter and their supporters who were fighting strongly over the position of cantor in the old synagogue)[ii]. The communal council, headed then by Chaim Wolf who was one of the partners of the Profinancial and a very wealthy man, agreed to this recommendation. The supporters of Cantor Schechter, headed by Mosze Scheinbach, did not regard this as a good omen[iii], for they suspected the Gaon of supporting the opposing side.

[Page 82]

The name of Mosze Scheinbach appears for the first time here in the annals of the events of the community. He was to become the central figure of the community for approximately the next fifty years. At that time, M. Scheinbach was already a member of the communal council and the head of the “Schechterites”. He came from the village of Brzozowa near Dobromil, not far from Przemyśl. He came to the city along with the general influx of those seeking a livelihood, which was abundant in the city as it was becoming a military center. At first, he earned his livelihood from two sources: wagon driving and the transport of materials, and a popular restaurant (by his wife). When he abandoned these forms of “livelihood”, those who opposed his rise to power would often remind him of his early sources of livelihood, that when he first came to Przemyśl he was not even able to sign his name in Latin characters, and that his education from the cheder was almost nil. They added further that when he came to Przemyśl, he did not broaden his education that he had obtained in the village. His opponents were incorrect, for not only was the man intelligent, but he also learned greatly from life experiences, even though he did not read too many books after he had learned how to read. He became especially proficient in the “government” tasks that he took on, not only in his synagogue and the community, but also in the city council and its institutions, as well as in the “Old Bank”, the running of which he had great influence over.

In any case, Scheinbach apparently succeeded in his early sources of livelihood. This success enabled him to exchange them for other, more successful pursuits, to dress in a fine fashion, to conduct his household in a manner fitting of his status, and to educate two of his sons as lawyers and the third as a pharmacist. He joined the community council, the town council, and became an asesor (assistant judge) to the magistrate. He learned well the norms of behavior of the intelligentsia in general, and of government officials in particular.

M. Sch. had a strong character and strong drives. In particular he had a drive for leadership. His opponents issued complaints about him through printed notices that during election times, those under his sphere of influence would vote in place of people who were deceased or absent from the city. We do not know of any court cases that took place because of the disgrace that he suffered. However, his political opponents also behaved in this manner during election times. This does not justify the situation, but it testifies to the fact that this was the “way of the land” during those times, even though it was a corrupt and immoral behavior.

When the “Zion” organization was founded in 1894 and 300-400 people joined in short order, M. Sch . was among them. However, when it became clear after a few years that the government of the land does not look positively on the awakening of the Jewish national consciousness, M. Sch. became “a Pole from the womb and from birth”. However, is it possible to demand special loyalty to one's nation from a person who received minimal traditional education and never studied in public schools, when at that time Jews throughout Galicia who had a strict religious upbringing and at times also secular education knew how to play the “Polish” game and to betray the honor and interests of their people? There was a general moral decline at that time.

Thus was the man and thus did he act. We should not be surprised that due to his intelligence and talents, he succeeded in becoming a decisive voice in the city a short time after the battle of the cantors. Through his mouth it was determined who would or who would not be elected to the communal council and the town council, who would become head of the council and who would struggle for it forever. Candidates for parliament, even during the time of universal secret suffrage and especially before it, knew that they had to give over the running of their affairs to M. Sch. if they wished to have any chance of success.

With his great intelligence, M. Sch. declined the title of “head of the community”, and preferred de facto leadership, leaving the figurehead titles to others. This situation did not change, and M. Sch . knew how to protect his leadership of the communal council even during the era of universal suffrage rights for parliament, by maintaining his support of the small number of electors for the community. He would send primarily wealthy or at least well-off people to the communal leadership, from among

[Page 83]

practitioners of the free professions who earned good incomes, and from among the traditional Jews – primarily scholars and Hassidic leaders – and even Zionists and socialists, “silent ones” of course, on the condition that they would protect his status and leadership over the community. His prime goal was to preserve his authority in the city council and the city. During M. Sch.'s final decade of life, he set up a certain veteran lawyer as the head of the communal council, who operated according to his dictates.

For the Jews of Przemyśl who knew the city from the time prior to the First World War, it is worthwhile to mention the composition of the city council from the year 1907, in order to see over whom this man dominated, and who nodded their heads to him. The smaller council included: the lawyers Goldfarb and Haas, the engineer Reiniger, Melech Gans, Mosze Hirt, Leo Langbank and Arnold Rabinowicz. The rest of the members of the council were: Aberdam, Leo Aschkenazy, Josef Isaak, Shalom Baumwald, Menachem Brodheim, Leib Bombach, Shimon Gottfried, Leizer Grossman, Arco Dawid, M. L. Diamant, Baruch Henner, the lawyer Berthold Herzig, Yaakov Hirschfeld, Naftali Winkler, Aharon Landau, Dawid Lander, Yehoshua Mieses, Samuel Knoller and Leo Schwartzthal. It is typical that craftsmen are missing from this list.

The administrative office of the community was restricted until the outbreak of the First World War. Its budget was modest, reaching approximately 112,000 crown in 1907/08 and 140,000 crown in 1913/14. These are small sums in light of the number of taxpayers, and the good economic status of a significant number of the Jewish residents of the city. However it must be noted that most of the communal institutions, or those institutions dependent upon the community, existed through their own income, and even ran a surplus. Such institutions included the synagogues and slaughterhouses on the one hand, and the bathhouse and cemeteries, including the Chevra Kadisha (burial society) on the other hand. The expenses for the rabbinical courts of law were not great, for the community paid their members modest salaries, and fees were collected from those who were interested in the services of the court and its members. The hospital and old age home were founded through funds (foundations) established by two very wealthy people (the Hirts) who supported them even after they were built. This was over and above the payments that these institutions received for their services. The allocation to the Jewish schools was not large, for the simple reason that their numbers were not large and their academic level was low (there were two Talmud Torah buildings). There remained the “Agudat Shtei Haagorot” (The Group of the Two Coins), and the People's Kitchen that required communal support. Other benevolent organizations received small allocations. Jewish public schools (elementary schools and gymnasiums), the orphanage, the bourse for apprentices, the trade school for girls, and the institution for support of academics all did not exist yet. They were founded after the First World War.

In reality, no task was left to the responsibility of the community, and there were no factional disputes within it. If any controversy ever arose, Sch. thought, “let the children get up and play”. Sch. displayed strength of spirit and great feelings of obligation to the members of our community in that he did not join the wave of those who fled westward in 1914 as the Russians approached the city, but rather remained in the city, serving as vice chairman of the community, out of a sense of responsibility to the community. This was similar to what Rabbi Schmelkes did. He and the members of the community suffered from tribulations and great danger during the time of the siege, and even more so after the conquest of the city by the Russians. He should be remembered positively for this relationship with the community.

Mr. Sch. Apparently died in 5677 (1917) or one year previously, after he returned from Lvov, to where he had been sent into exile by the Russians.

Original Footnotes:

by D. N.

Translated by Jerrold Landau

According to the national law of 1889, Przemyśl was included among the 30 largest cities in Galicia (excluding Lvov and Kraków), in which the city leadership (magistrate) was composed of 6 members: the mayor, the vice mayor, and 4 directors called asesors who were elected by the city council. The number of members of the city council was set at 36

[Page 84]

and 18 backups. Elections to the city council took place in 3 electoral strata. Each elected 12 members to the council, even though the sizes of the strata were different. The first stratum included members of the clergy, the free professions, government officials, and officials of communal institutions. This composition guaranteed at the outset the election of 12 Christian members. On the other hand, the majority of electors of the other two strata – which were determined by the level of tax that was paid – were Jews. Thus, the Jews were indeed able to win most of the seats of the city council in most of the town of Galicia. However, in order to avoid anti-Semitism and the accusation that Jews were ruling over “Christian” cities, the two sides reached a compromise agreement in almost all of the cities of Galicia. From among the 36 seats on the magistrate and 18 backups, the Jews were assured half of the seats, as well as 2 seats on the city leadership (the magistrate). This was also the situation in Przemyśl at that time. This situation continued until the end of Austrian rule in 1918.

The first Jewish membership of the city leadership, the asesors, were apparently Dr. Wilhelm Rosenbach and the photographer Baruch Henner. Dr. Rosenbach, a native of JarosŁaw, was a lawyer and veteran jurist. He was an expert in administrative law and had great talents. He was elected to the city council in 1885/86 and served for approximately 30 years as the overseer of the city budget and an asesor. He also served for many years as the vice administrator of the council of lawyers of Przemyśl. He was a faithful Jew, who studied Jewish sources in his youth. He died in 1922 at the age of 82.

The second asesor, Baruch Henner, a native of Wielkie Oczy, studied in a yeshiva during his youth. However, not only did he begin studying secular studies from a young age, but also he dedicated himself to the professions of photography and graphics that were created in those days. He reached a high artistic level. His work won awards outside of the country as well, and he received the designation of “Photographer of the Royal Court of the Kaiser”. He was elected to the city council in 1890.

He fulfilled other public roles in addition to his work on the city council, including serving as the director of the allocations committee and the director of the sick fund. He was widely appreciated by the residents of the city due to his honesty and hatred of bribery. He died in 1926 at the age of 85.

With the ascendancy of Mosze Scheinbach, an activist of the 'do-it-all' variety, Baruch Henner's place on the city leadership council was replaced by Mosze Scheinbach, who served for many years after that as a member of the magistrate. Even though the Jewish representation in the city council was at a significant level, and they had influence over matters that were within their authority, such as overseeing of building, protection of health, supervision of commerce and trade, and maintenance of the public schools, there were few Jewish supervisors in the city council and its institutions. These officials included the city doctor Dr. Mannheim, Braunstein (in the building department), the head of a well-known family in the city Leon Axer, the treasurer, and the lieutenant of the city police Waldman. Mrs. Henner was a Jewish official in the allocations department. We have no information as to the degree of support provided by the city to Jewish institutions at that time. It is know that the city hall provided significant financial assistance toward the building of the new synagogue on Slowacki St., but this time it was due to the payment of the coalition tax to Mosze Scheinbach for the Jewish votes from 1907. With the strengthening of Dr. Lieberman and the socialists of the city, an attempt was made to weaken the coalition that existed in the city hall, and which had the reactionary appearance of yes-men. An opposition coalition was established to this end. Only a few years before the outbreak of the First World War did the opposition coalition succeed in electing a few members to the city council, including 2 Jews: the lawyer Adolf Mester and the well-known contractor Szymon Bernstein. Both of them, like most of the Jews in the city at that time, were supporters of Dr. Lieberman. After the war, Szymon Bernstein was among the activists in the nationalist Zionist camp. The autonomous activities of the city council were stopped by the government appointed commissars during the war years of 1914-1918.

a. Wholesale business in several types of merchandise was conducted on a national scale. First and foremost, there was business with iron materials, iron implements, foodstuff, and general stores. The Buchband, Langsam and Wikler families worked in the iron business. The 4 Ganz brothers with their branches (Baumwald [Baumfeld], Turnheim, Mieses, Majersdorf, Scharf, and Astel) worked in foodstuffs. Tovia Intrater, Tuchmann and Nisan Sacher did business in specialty food stores. Yaakov Hirschfeld and Moshe Klang worked in the flour industry. The grain merchants ground their wheat that they purchased for flour in the small mills of Frankel. The market of these merchants of provisions extended from Stryj in the east to Rzeszów in the west. The iron wholesalers distributed their goods throughout all of Galicia. This was also the situation with the wholesale army supply business of Reuven Necht. The missile industry was also large scale, as raw manufacturing for export to western Austria. In this respect, it is fitting to mention the concerns of the Miltau and Kupfer families, who had general purchase contracts with the army and many dry goods warehouses in the city and the region. They would also purchase missiles from the villages around Rzeszów. Aside from them, Antman was a large provider of animals for the army. He would gather them together and ship them to the west. The firms of Blech, Goliger, Nagel, Moshe Katz, and Kerner [Körner] and sons were large wholesalers for building lumber. They would also provide for the army, and their marketplace encompassed a large part of Galicia. Freund's publishing house (previously Amkraut and Freund) was among the largest wholesaler in Galicia of sidurim (prayer books), machzorim (festival prayer books), techinot (women's petition books), and other holy books. These reached all corners of the world. He was also the publisher of the books that were printed in Przemyśl by the Knoller publishing house. The Dornbusch business was a wholesaler of large women's kerchiefs. His market reached to Rzeszów.

b. Przemyśl was a center of large agencies for a wide range of large enterprises. Among others, we must mention here the large form of Klagsbald and Honigwachs (agricultural machines and sewing machines that were sold throughout Galicia); Aschkenazy and Munz, the national agency of the large Hungarian firm “Rima Morani” (iron products); Shlomo Aschkenazy, the agency of the largest flour mill in Hungary; Arnold Rabinowicz, the national agency of the Unger Insurance Company; Feuer, the agent of another large insurance company from abroad Kerner [Körner].

c. Important merchants worked in the retail trade: men's and women's fashion – Reif; valuable gold objects – Löwenthal; fine porcelain wares – Rosenberg; fine men's fashion – David Streng; furs – Berl Brodheim and Bernfeld; haberdashery – Benzion Rosenzweig, Mrs. Halpern and Marcus Duldig. The latter also did business with popular sweaters. These haberdashery merchants also conducted large-scale wholesale business. The veteran of the haberdashery business in Przemyśl was Reb Hershele Sperling, who, as was said, used to travel by carriage to Vienna to purchase merchandise (before 1859). Kalman Gotlieb owned a fine furnishings store. There were many stores for low prices ready made men's clothing in Przemyśl. Some of their owners became wealthy. Stores for delicacies intended primarily for captains of the army were prominent on the streets of the city (2 of the Ochsenbergs and that of Buchband, etc.)

[Page 86]

d. Manufacturing. The most important manufacturing enterprise in the place was the stream driven flourmill of Frankel and partners, founded in 1866. Already by 1883, it had 9 millstones and 60 horsepower steam engine. According to the information that we received about this matter from Yaakov Kerner of blessed memory, this mill milled 10-12 wagonloads of flour a day, and was in its time the largest flourmill in Galicia. 50-60 Christian employees worked there, and there were approximately 11 Jewish foremen. In his time, Mester served as the general director. He was the father of the lawyer Mester [Henryk (Heinrich) - ed.] and the judge Mester. At the end of the 19th century, Dawid Löwenthal served in this role. The elder Frankel who founded this mill was a lawyer who hailed from Lvov. His son Alfred became the sole owner after he gradually took over the shares of the partners. In the latter years before the last war, the Nussbaum family established a smaller mill. It contained new electric machinery that worked effectively, and apparently never stopped for lack of work. A small flour mill also operated in Zasanie. During the Austrian era, the owners of sawmills of the region lived in Przemyśl: that of Stummer in Niżankowce, and of Engel and Hutterer in Osieki. However, none of these enterprises reached a national level, as they did in Stanisławów. Among the industries in Przemyśl, we must also mention the brick kilns, especially of Freundenheim, Teich and Mrs. Mieses; the kauczuk [a] clothing factory (especially of collars) that belonged to the firm of Lieber and Partners, and which employed approximately 50 Jewish workers. There were several factories for packing materials, and for cigarettes, and the cork factory of Eliezer Kartagener. Jewish employees worked in all of these, sometimes more than 10 in a factory.

e. There were many army suppliers in Przemyśl, some of whom became quite wealthy. We will mention here Eliahu Hirt (who built the new Jewish hospital with his own money), Mosze Hirt (who established the old age home with his money and supported the popular minyan in the square “By the Gate” – Plac Na Bramie – ed.), Spiegel (provided food to the army hospitals), David Goliger and Berish Kerner (lumber for building), various food providers, etc. The Kerner [Körner] family provided elm wood for the army as far as Klosterneuberg near Vienna, and throughout Galicia. Incidentally, they also provided oak wood to the Tunt factory in Vienna. Baruch Saltz provided dyes to the army.

f. Large scale army contractors for building included Szymon Bernstein, Wagner, and the engineer Reiniger from among the Jews, and Holiczer and Habliczak firm from among the Christians (they were brought in to Przemyśl by the army). Szymon Bernstein, who possessed great Jewish and general knowledge, had exceptional experience. He built an army road in the area of three commands of the Galician army, starting from Bukovina and ending in Silesia. The engineer Reiniger, who came to Przemyśl from Moravia, erected army buildings in Przemyśl and the region, and also performed periodic repairs on those buildings. Wagner in his time brought new styles of building to Przemyśl.

g. Inns. The professional statistics in the last two lists of the era show the importance of the hospitality industry, with decisive numbers and significant statistics (approximately 6.7%). This includes restaurants, cooking houses, dairies (which were in reality vegetarian food suppliers, appreciated very much by the soldiers and the sergeants), coffeehouses, beer halls, hotels, and rooms for rent. The coffeehouses especially flourished. Some were splendid with none like them in Galicia except in Lvov and Kraków. The dairies also flourished.

h. Many craftsmen, especially of the building trades, came to Przemyśl from all corners of Galicia. Many of them were of a high professional level, such as the well-known painter and sign maker Frim, who was frequently commissioned by the army for improvements and new work He also performed artistic work for the residents. There were also the professional smiths, of whom it is worthwhile to point out Armhaus, Wolfling, Schlisselberg and sons; as well as the blacksmiths, the designers of decorations for the borders of houses, the manufacturers of oven doors for the houses of the nobility, (well-known

[Page 87]

in his time was Yehuda Ehrlich), the manufacturers of special fillings for furniture, or the sewers of the frocks of the priesthood: such as Leib Pasternak, and later Leib Pillersdorf. The furriers of Przemyśl also produced excellent wares.

i. Financial. Incidentally it has become clear that during the era that we are dealing with, there were a significant number of wealthy people in Przemyśl – of course on the Galician scale, in comparison to the general impoverished population. Among them were some very wealthy people who lived solely from the income from their own wealth. Others were merchants, contractors, manufacturers, suppliers, etc. The evaluation conducted by Mr. Hirsch Intrater, who is considered an expert in this matter, serves as proof of this. During that time, he was an important writer of contracts (a middleman between the money lenders and their private borrowers). He knew the economic status of each and every Jew through his extensive experience. According to Moshe Intrater, Hirsch's brother, once both of them went over the list of people who were considered wealthy in possessions and cash. In their clear evaluation of their property, the brothers reached the sum of 50,000,000 crowns (according to the rates of that time, more than 10,000,000 dollars). It is difficult to estimate what portion of the Jewish wealth was used for private loans. There were always several contract writers working in the city. Similarly, there were also Jews whose profession was the giving of loans.

j. Jewish banking institutions. There were several important Jewish bankers. First and foremost, there was the banking institution of Aschkenazy and Munz, of Leopold Süsswein (later the director and apparently a partner of the “Vienna Bank Union”), and of Yaakov Ehrlich. Aside from these, approximately 12 credit cooperatives that were in Jewish hands functioned as banks. The eldest of them was the “Old Bank” whose first director was the father of Professor Schorr. Mosze Scheinbach had decisive influence over this bank. This assisted him with his political hegemony over a segment of the Jewish population. Later, the “Giro”[b] bank was created, which encountered financial difficulties in the final period, that it was not able to overcome. Among the others we should note the “Spółdzielczy Bank” (of the people of the large Beis Midrash, headed by Yaakov Hirschfeld and Yaakov Sacher); the Zaliczkowy Bank[c] (Nussbaum, Ehrenfreund, Abraham Rebhun); the bank of Wikler and Silberfeld, the bank of the Teomim [Tumim] brothers; the bank of Hirsch Steiner; the bank founded by Billig (and his brother in Berlin); Kasa Faktorow[d] (founded by groups of merchants and lawyers). The interest rate of these banks, including auxiliary fees, was not always low. Aside from these institutions, there were several wealthy Jews who were “censors” in the Giro Bank of Austria-Hungary, who served as guarantors for the loans. With respect to their credit for this bank, they would promise credit at relatively low rates of interest to those who brought contracts to the royal bank. The city savings fund also ensured a number of loans for the needs of the Jews. This was also the case with the Galician Hipoteczny Bank[e].

k. The profinancers of Przemyśl. Freudenheim, Wolf, Reisner and Herzig conducted the local profinancing, except in the final years of the existence of this business. This was the most important business of its kind in the entire country, due to the large contingent of the army in the city and the area. It was the pillar of support of the Jewish economy of the city. It employed a large staff of workers, which included non-Jews only among the “Roizors” at the outskirts of the city. A large number of Jewish bartenders worked in all corners of the city. In addition, the profinancers of Przemyśl conducted large-scale profinancing also outside of Przemyśl, for example in Stanisławów and JarosŁaw. Many of them owned other large businesses. Freudenheim owned a large brick kiln. Wolf and Herzig were involved in the business of regulation of the rivers. They also were partners in banks and in the building of houses.

l. Builders of buildings. Various professionals such as merchants, moneylenders, manufacturers and even successful lawyers would build houses for themselves, sometimes even splendid ones. Thanks to the large numbers of high captains, there was a great demand for large residences. This affected the prices of mid-sized residences. The building of houses was not only a sure investment, but at times also the source of great profit.

[Page 88]

Furthermore, the building of smaller, simpler residences was associated with speculative development in the fields of the suburbs. The builders of such houses did not intend to hold on to them, but rather to sell them at a profit, so that they could build other homes, around and around again. In this manner, Schiffer built many houses on Długa St. (later on Dworskiego), Teich on Dobromilska (later Słowackiego [Słowacki St. - ed.]) and to a smaller degree Dampf in the Wygoda suburb. Schiffer left behind a large amount of property, some of which was houses, to his three children who were his heirs, who proceeded to lose it. Teich and Dampf lost their fortunes during their lifetimes.

m. Estate owners. Only very few of the large estate owners in the area around Przemyśl were Jews. Similarly, there were also few Jewish lessees of such estates. From among the estate owners, we should mention Reb Moshe Teomim [Tumim] (who owned the Trojczyce estate). He lived in Przemyśl, and was the wealthiest Jew in the city; as well as the estates under Jewish ownership in Bolestraszyce, Nakło and Rokszyce. The Baruch family, which had lived in Nakło for generations, was among the lessees of large estates. Many of the family members were traditionalist maskilim. (Reb Yonah Rosenfeld, the maskil who upheld tradition, educated the younger generation of the family in his time.) From the time that Przemyśl turned into an army center, agriculture on estates around the city ceased to be an attractive source of livelihood. People felt that there were greater opportunities for investing money in the city. The famous and very wealthy agrarian Reb Berish Turk lived in the city before its militarization. He is buried in its cemetery, and was known throughout Galicia as a great philanthropist.

Conclusion. To sum up, it cannot be said that there was an economic Garden of Eden in the city starting from the time of the militarization. As proof of this, the stream of emigration from the city to Vienna, Germany and the United States grew during the 1880s and 1890s. The conditions for immigrants were still difficult in the 1890s. The “shops” sucked the blood of their employees with hard work, and the “peddlers” did not earn a great deal at their lowly trade. The first mutual benefit and sick benefit society for Przemyśl natives was established in New York already by 1899. Other organizations were founded later.

Apparently, there were also people in Przemyśl who were unable to earn their livelihoods there even if they were willing to work hard and suffice themselves with little, despite the situation described. No permanent Jewish proletariat was established there, as it was in Kołomyja for example. The workers at the workshops attempted to attain the level of “meister” and to finance their own workshops by means of loans and dowries. Apparently, there were also those who searched for other means to attain a stronger status. Przemyśl perhaps had the least unfavorable conditions of other Jewish centers in Galicia, where the percentage of Jews was larger than in Przemyśl.

Original Footnote:

Coordinator's Footnotes:

by D. N.

Translated by Jerrold Landau

1) It is hard to believe, but it is a fact that the first Hebrew publishing house in Przemyśl was founded at the end of the year 5629 (1868), as Reb Chaim Dov Friedberg mentioned in his book “History of Hebrew Printing in Poland”, page 164, which appeared complete and accurate, published by Mr. Baruch Friedberg in the year 5710 (1950) in Tel Aviv. At first, this was only a branch of the publishing house of Reb Dov Berish Luria, who owned printing presses in Lvov and Żółkiew. They began by publishing the book a new edition of “Shirei Tiferet” of Naftali Hertz Wiesel. Even before the publication of this book was complete, he joined in partnership with Reb Chaim Aharon Żupnik after a year. Two typesetters worked in the publishing house then. Proofreading was done by the maskil who was a writer in Przemyśl, Reb Naftali Weinig. However, the arrangement fell apart after a short time. Mr. Zupnik founded his own typesetting business and the printing was done, starting from 5631 (1871) by the Greek-Catholic Kapituła publishing house in Przemyśl. Reb Chaim Knoller joined the partnership in 5633 (about 1873). He was a writer of Torah subjects and a well-known Sanzer Hassid. In the year 5648 (1888)

[Page 89]

Mr. Hammerschmid [Hammerschmied] joined as a third partner. He was the father of the lawyer Hammerschmid [Hammerschmied]. Ten years later (5658), Mr. Wolf entered in his place. In the year 5670 (1910), the partnership passed to Reb Chaim Knoller and his son. Reb Chaim Knoller died at the end of the First World War, and the publishing house passed to his son alone. He transferred it to his son-in-law Szymon Mieses when he made aliya during the 1930s. He also prepared to make aliya, following his father-in-law, but he did not succeed, and he perished in the Holocaust along with his family. It is worthwhile to note that decades earlier, the printing press of the Greek Catholic Kapituła was turned over the partners to run (it is not known if they did so as owners or lessees). It thereby turned into a mixed Hebrew and vernacular publishing house. During the time of this partnership, the publishing house published Torah books, Hassidic books, and all of the many books published by the Przemyśl writers Amkraut and Freund (formerly Ethel Amkraut). This was one of the largest publishing houses of siddurim (prayer books), machzorim (festival prayer books), techinot (women's petitions), and other religious books in Galicia. They were distributed throughout almost all parts of the world. In addition, they also produced various templates for the Greek Catholic clergy, as well as certificates for the births of Jewish children, invitations, and Hebrew and vernacular posters. During the period before the First World War, the proofreader was Reb Tzvi Hirsch the son of Reb Yitzchak (known in the city as Hershele Reb Yitzchak's). He wrote a book on the history of Przemyśl that was never published, and was lost during the war.

|

|

The title page of Sfateinu, a textbook for the study of the Hebrew language, in the natural style. Published by Simcha Freund in Przemyśl. |

2. According to the aforementioned story of Friedberg, before the Second World War a publishing house by the name of Freund Orphans existed in Przemyśl. This was apparently the Freund publishing house. However, Freund's heir, Reb Aharon Freund who lives in Israel, knows nothing about this. It is possible that the binding of books that were printed Knoller publishing house by the Freund publisher was taken over from Knoller by the Freund family, however they never published independently.

3. There was another publishing house, primarily for vernacular languages, that was owned by Schwarz, the owner of a textbook store. Later it became the partnership of Schwarz and Robinsohn. This publishing house dealt mainly with vernacular books. Only announcement posters and advertising flyers were published in Hebrew.

We know some additional personal information about Reb Chaim Knoller, who was mentioned above as the constant partner in the printing press for decades. He was the elder brother of Reb Shmuel Knoller. He was completely immersed in Torah literature, study and dissemination of Torah for the sake of Heaven, as well as editing books on Torah subjects. Knoller conducted himself with uprightness and fine character during his life. He related to his employees with respect. To this end we should mention that the Christian Józef Styfi, who worked as a mechanic in his printing press for some time and later became an important independent printer in Przemyśl, eulogized him emotionally at his grave. This fact testifies to the relationship that this religious Jew had with his employees, and to his high moral character. Reb Chaim Knoller, who taught lore, Midrash and Torah in the study halls of the city, was one of the leaders of the Sanzer Hassidim of the city. From among his books we should note “Pri Chaim” (The Fruit of Life), and “Dvar Yom BeYomo” (Matters of Each Day in its Day).

Political Movements in the Jewish Street

by D. N.

Translated by Jerrold Landau

History of the Zionist Movement in Przemyśl until the First World War

According to Dr. N. M. Gelber[1], an organization named “Yishuv Eretz Yisrael” (Settling of the Land of Israel) was founded in Przemyśl in 1875 by Menachem Brodheim, a teacher of religion in the school of the city, and the Hebrew teacher Awigdor Mermelstein. Its purpose was to collect money for the benefit of “Mizkeret Moshe” that existed at that time in London with the aim of improving the situation of the settlement in Israel through working the land. Nothing is known about the activities of that organization, and about whether similar organizations were founded in other areas of Galicia. (There is an article on that subject by Brodheim in Hamagid.) Apparently, this was an unsuccessful endeavor. In any case, to the best of our knowledge, there is no memory of such an organization in our city.

However, there is memory of the founding of another organization in Przemyśl called “Dorshei Torah Vadaat” (Expounders of Torah and Religion). It was also founded in the 1870s by a circle of maskilim in Przemyśl who appreciated tradition. Its goal was “the dissemination of Hebrew language and literature”. Dr. Gelber states[2] that the forces behind this organization were Izak Shaltiel Gerber (a native of JarosŁaw who apparently lived in Przemyśl at that time), Heinrich Münzer (later a resident of Berlin), Awigdor Mermelstein, and Yaakov Ehrlich who served as its first chairman (a man filled to the brim with Hebrew culture and secular knowledge, and at the time very much in demand as a lecturer in German). We know that Josef Frei [Frey, Freu], the father of Dr. Nachman and Dr. Mordechai Frei [Frey, Freu], Zionist activists in Tel Aviv and formerly in Vienna, was also a member. According to what was written in Przemyśl in December 1881 in Ojczyzna, the newspaper of the assimilationists (number 1/82), this organization was founded in 1887 and was still active at the time of the appearance of the article. The following activists are mentioned in the article: Ehrlich, Auerbach, and the religion teacher Baumgarten. This organization maintained a fine library which included books on Judaica in the German language, as well as a reading hall. After it disbanded during the 1890s, the library transferred to the Yeshurun organization and from there to the Zion organization.

It is possible to state that the Dorshei Torah Vadaat organization played an important role in moving the hearts of the local intelligentsia who had some knowledge of Hebrew toward the Zionist idea.

It is appropriate to dedicate some lines to describe that era of Zionism, which was quite strong in Galicia, and promoted the nationalist idea starting from 1892, approximately four years before the publication of Herzl's “The Jewish State”. In Galicia, the name “Tzionut” (Zionism) appeared explicitly, rather than “Chibat Zion” (Love of Zion), and its members were known as “Tzionim” (Zionists) rather than “Chovevei Zion” (Lovers of Zion). A movement called Chovevei Zion never existed in Galicia, as it did in Russia and Western Europe. Even the movement (centered in Tarnow) that was founded by Herzl at the end of the 19th century and wanted to dedicate itself to practical settlement never affiliated with the Chibat Zion of Russia. Due to the difficult political situation, the Zionist awakening in Russia was limited in its activities and was unable to develop into a political movement, as did happen in Vienna in the 1880s and later in Berlin. Chapters of this movement arose in Galicia, Bukovina, and the rest of the provinces of Austria. In Galicia itself, the traditions of the Haskala movement, traditional education and Hassidism served as fertile grounds

[Page 91]

for a broad-based national movement. In early 1892 in Galicia, after a period of 10 years of preparation, and based upon the achievements of Western European political education, this movement began to publish weeklies and bi-weeklies in Polish and Hebrew whose intention was to serve as the foundation of national and cultural renewal of the nation. At that time, Shlomo Schiller wrote his Polish book, “The National Existence of the Jews” (1894). Even before him, the booklet, “What the Program of Jewish Youth Should Be” was written. Young, energetic ideologues appeared on the communal stage: Ehrenpreis, Yehoshua Thon, Braude, Abraham Kurkis [Kirkes], Adolf Stand, Gershon Zipper, David Malz, Feld and others. Rabbi Leibish Mendel Landau of Przemyśl became known as a modern activist and organizer (despite his rabbinic training). He traveled from city to city, convened meetings and preached not sermons, but lectures filled with national educational content. As a sign of this national revival, a Maccabee celebration was performed, that gave expression to the ideas and feelings of the youth of the movement. This was not a traditional Chanuka celebration (that had family warmth), but a festival of the exalted spirit of the youth who saw the Maccabees as a symbol of the spiritual strength of the nation. The preacher attempted to arouse the personal and national pride of his listeners, and to make the servitude of the exile odious to them. Another illustrious Przemyśl native, Abraham Sonne once said that the Maccabee Celebration became the primary celebration of the modern Zionist movement. Thus was the pre-Herzlian Galician Zionist movement that later began to capture the hearts of Galician Jewry, especially of the youth.

|

|

Rabbi Leibish Mendel Landau |

In the wake of this movement, the “Zion” organization arose in Przemyśl in 1893, and at the beginning of 1894, the “Yeshurun” organization. The first was legally registered as a chapter of the “Zion” organization of Vienna. Ideologically, it was connected to the Galician Zionist movement that was centered in Lvov. The second was a national movement faithful to Hebrew culture. In practice, if not in actuality, it was faithful to Zionism. Yaakov Ehrlich; Rabbi Leibish Mendel Landau, a student of Rabbi Yitzchak Szmelkes who knew how to speak and also to give classes in the Hebrew language; Awigdor Mermelstein the principal of the “Tikvat Yisrael” Hebrew school, and the merchant Samuel Schweber all worked in the Zion organization. The first chairman of Zion, chosen in December 1893, was Rabbi Mordechai Szmelkes the father of Rabbi Gedalia Szmelkes and the brother of Rabbi Yitzchak Szmelkes. Before he left the city in 1893, he did not hesitate to join the Zion organization, which testifies that at this time, there were still possibilities of membership in the movement for a prominent traditional rabbi such as he. It is worthwhile to note that Rabbi Leibish Mendel Landau, who was later a candidate for the rabbinate of Kołomyja and JarosŁaw , was chosen as the vice chairman of Zion. In the Yeshurun organization there was Dr. Kutna, the merchant Yehoshua Mieses, and Shlomo Auerbach who was a high official in the post office (formerly a student in the school of Yosef Perel in Tarnopol). During its first years of existence, the Zion organization had between 300 and 400 members. This shows that it was a particularly popular organization in light of the fact that the entire Jewish population of the city was about 10,000 at the time. Characteristic is the fact that Mosze Scheinbach, who at that time had begun to ascend the ladder of communal activism of the city, found it appropriate to join that group. The Yeshurun organization, which at that time was a vibrant educational movement, registered itself as a Zionist organization in the ledgers of the Zionist center in Lvov, even though this was not part of its charter.

There were two national organizations in the city. This is an interesting communal-national phenomenon, considering the conditions of the time and lack of forces promoting activity. We should know that in these two organizations, especially Yeshurun,

[Page 92]

there were no activists who knew how to speak in Polish. Therefore, almost no Polish speakers joined these organizations, especially from amongst the intelligentsia, the many employees of the civic institutions, the lawyers, doctors and engineers. The situation was different in most other cities of Galicia where many academics and practitioners of the free professions joined the movement. Favorable conditions for Jewish assimilation developed in Przemyśl, for the percentage of Jews was smaller than in similar cities such as Kołomyja, Stanisławów, Tarnopol, and Tarnow.

During the beginning of the 1890s, the “Czytelnia Naukowa” organization arose in our city. It was not officially Jewish, and there were always 2-4 non-Jews who were members, but for all intents and purposes it was a Jewish organization. We should note that almost the entire Polish speaking Jewish intelligentsia were members of this organization. No similar organization is known to us from any other place in Galicia from that time. We should also note that the activities of Dr. Liberman, who came to Przemyśl around 1893-4, attracted from the Zionist organization some of its supporters, not only because of his socialist activity, but also for the linguistic character of his activities which were conducted in refined Polish. From year to year, the number of the members of the intelligentsia who completed their studies in high schools and universities increased, and the number of people who received partial German education in their homes decreased. Along with this, the number of new members of the two organizations obviously decreased.

There was an additional factor that inhibited the development of the Zion organization. The religious members, of which there were a large number, began feeling a sense of discomfort in their homes and synagogues. Many left the organization for this reason.

Furthermore, members of the free professions did not look favorably upon the Zionist intelligentsia at that time. Dr. Kornhauser, the only Zionist lawyer in the city at that time – who in reality was only a clerk who presided over the development of the legal organization – left the city in 1894 and opened up his office in Jasło. He was one of the 2 or 3 people in Galicia who remained faithful to the active Zionist committee in Vienna at the time of the appearance of the Herzlian movement.

In 1898, the Zion organization began to write its protocols in substandard Polish. Polish was not spoken at its meetings, and no lectures were arranged in Polish. In the pre-Herzl era, there were at time visits to Przemyśl by Zionist activists and intellectuals who appeared at meetings and Maccabee celebrations. However, their visits did not fill the lacuna in the local leaders and educators who were responsible for educating the younger generation. Indeed, two Zionist activists of national stature lived in Przemyśl – Rabbi Leibish Mendel Landau and Awigdor Mermelstein. However, their local activities weakened in the years just before Herzl. Rabbi Leibish Mendel was busy trying to obtain the rabbinical seat in one of the cities of Galicia, despite the opposition of Belz. He finally tired of this struggle, gave up on Galicia, and accepted the rabbinate of Botosani, Romania, to where he moved his family in September 1897, immediately after the First Zionist Congress. Starting from 1895, Mermelstein was completely occupied with the running of his school, which then had 4 or 5 grades, and with protecting it from the attacks of the Orthodox. At times, he was involved in the writing of Zionist publicity pamphlets in Yiddish (The Zionist Order, Chanuka Lights, A Letter from Zion to her Children), the influence of which was very weak in enlightened Przemyśl. He was able to assist the committee of the Zion organization in administrative matters only. He distanced himself from publicity work among the opponents of Zionism in the city. His authority in the city declined. In the minutes of the meetings and events that we have covering a span of 8 years, there is not even a small mention of his supporters trying to set him up as the chairman of the movement.

We do not know how the Herzlian idea was received in Przemyśl, but there is no reason to assume that it met

[Page 93]

|

|

|||

A page of protocols of the Zion organization, hand written in Polish |

||||

[Page 94]

any opposition. There was no opposing movement in the year prior to the First Zionist Congress. Its echoes reached the ledger of protocols of the organization starting from April 10, 1898.[i] In any case, there is no reason to assume that the advent of Herzl was not accepted in Przemyśl, which was a Zionist city at that time, with the same enthusiasm as was prevalent in the rest of the cities of Galicia and throughout Austria. Here, as in all of Galicia, the movement began using the term “Zionism” at least four years before the First Zionist Congress, and was organized and directed by Nathan Birnbaum as a modern political movement. The appearance of Herzl had the sole role of imparting great energy to this movement. The Herzlists did not fulfil this role in Przemyśl due to the lack of the professional Zionist intelligentsia and the nationalist academic youth.

Here are a few sections of the protocols of the Zionist organization in Przemyśl.

|

{Following is translation from the Polish:

| 14.8.1898 |

| 7.12.1898 |

Starting from 1898, a steady decline began in the Zion organization, which was the official representation of the Zionist movement in Przemyśl. Whereas in 1894, the number of members of Zion might not have reached 400, as was reported, but certainly exceeded 300; at the meeting of April 10, 1898, no more than 93 members showed up, despite the fact that the meeting was called to choose a new committee. The number of members steadily declined in the following years, until there were only 107 in 1903, despite the constant growth in the Jewish population of the city.

In 1904-1906 general meetings took place with the participation of approximately 40 members at times. Once, only 21 members showed up. The level of debate at the committee meetings was quite low, and the number of topics discussed was quite restricted. Fundamental issues were dealt with only occasionally.

Although in the first year of the existence of the organization, most of its members were Orthodox or traditional, the majority of them left over the coming years for justifiable reasons. We read in the minutes of a meeting of the committee from November 13, 1898, that a musical evening was proposed with the participation of women singing. One of the observant members of the committee objected, but the committee was silent about his objection. This was a sign that the influence of the Orthodox in the committee had already diminished.

It is interesting to note that at that same meeting, it was proposed to invite a speaker from Vienna to that musical-vocal evening – none other than Dr. Theodore Herzl himself. Of course, he declined the invitation.

Not much is known about serious lectures or publicity speeches. It was the custom to arrange a Maccabee Evening each year, to which they would invite speakers from outside the city. Przemyśl was only once able to send a local delegate to the Zionist congress. Jakob Ehrlich was a delegate to the 3rd Zionist Congress in 1899, as a candidate for the 94th position.

The second national movement, Yeshurun, also weakened during the Herzlian era, and disbanded in 1899. At the time of its disbanding, it transferred all of its inventory and library to the Zion organization, with the condition that Zion would pay the debts of the organization. The Zion committee agreed to this.

[Page 95]

Auerbach was the last chairman of Yeshurun. He was chosen in 1902 as the chairman of the Zion Organization. Aside from him, Henryk Godel served as chairman during the latter years of the Herzlian era. He had been the vice chairman during the time that Ehrlich was the chairman. There were also other chairmen who were registered on the citizens' lists (but were not natives of Przemyśl). However, as non-locals, they did not know how to conduct themselves in the organization or educational spheres.

While the Zionist movement was in a bad situation, a new Zionist generation began was coming of age in the gynmasiums of the city. This was a generation who read Zionist books and attached themselves to the Zionist ideal with enthusiasm. A few Zionist academics also appeared in the city. It is worthwhile to note that the youth of the gymnasiums began to work for and even participate in the committee of the Zion organization even at the time that they were still studying in gymnasium. This was fraught with the great danger of being expelled from school a short time before the matriculation exams. An incident took place with respect to the activities of the studying youth who were members of the Zion organization. At some time during the years 1903-1904, a number of students from the two gymnasiums of the city decided to attend the general meeting of the Zion organization in order to elect a new committee that would work for the revival of Zionist life in the city. Since these youths did not at all hide their “revolutionary” motives, someone who was interested in ensuring the failure of their plan wrote anonymous letters to the leadership of the two gynmasiums, informing them that the students of the two gymnasiums were going to participate in the general meeting of the organization. Therefore, that evening, the principals of the two gymnasiums went along with two teachers to the meeting on the fourth floor of the organization's headquarters. However, before they arrived, a youth who lived on the first floor ran and informed everyone about the arrival of the “delegation”. The youths left the meeting in disarray and hid in the rooms of the neighbors.

The youth began to get involved with the organization already from 1902 and onward. They later began to fulfil various roles to the point where they pushed aside most of the veteran member who left the organization. The organization gave over one of its three rooms, for a small fee, to a group of Zionist gymnasium students for meetings and communal study.

Still during the time of Herzl, the organization gave over on room to a group of storekeepers and bookkeepers, who took on that name “Achva” that was popular with such groups. The group numbered about 40 members at the outset. This was not a small number, considering the composition of the members, who up to this point had not been represented. However, the hopes to this end did not materialize, for only a portion of the new members were Zionists. It is not clear if any members of this organization transferred to the Poale Zion organization that was formed in the city one year later. In any case, we know that on April 8, 1903 Schlaf appeared as their delegate on the committee. He later became an extremist activist in the Socialist-Zionist movement of the city, and even became a propagandist of the S.S. movement (Territorialist Socialists).

At the time of the death of Herzl in 1904, the situation of the Zion organization was far from satisfying. Even worse, no new members of the committee could be found who were able to lead the organization to the high road. A new man did indeed appear as chairman, Kalman Robinsohn, who did attempt to fulfil his role faithfully. He did not have the vision necessary to enthuse his fellow committee members. Starting in 1903, Matityahu Mieses was chosen along with them. He was only 18 years old, but had exceptional general and Jewish knowledge. He was fluent in Hebrew, Yiddish, Polish and German. He worked on the committee for at least another two years. During that entire time, he fulfilled administrative roles and acted as treasurer.

Another attempt, made around 1906 by the young academic Josef Gelehrter, to found a new organization by the name of “Hatechia” also did not succeed, for this was the work of one lone person only.

The hopes of the Zionist youth for appropriate development began to be realized despite the local difficulties, albeit at a slow pace. This started with the circles of youth who left the Polish gymnasium in 1904. This was a group of 6 graduates with a Zionist conscience, strength of heart in promoting their ideas, vibrant in their emotions, and full of hope. This group dreamed of founding an academic Zionist group while they were still students

[Page 96]

in the gymnasium, and they waited impatiently for their matriculation exams. After they concluded, they began discussions with the university students who were older than they were, who had returned to Przemyśl for the summer vacation. Together they founded an organization that took on the name “Agudat Herzl”. There were 12 founders, including two partial Zionists who were taken in. The following are the founders:

1) Moshe Winter, who was later a judge in the regional court of Sambor. 2) Shlomo Turnheim, later an engineer in the United States. 3) Nathan Izak, later an engineer in Luxembourg. 4) Moshe Feuerman, a Doctor of Jurisprudence, a teacher in the Jewish teacher's seminary in Lvov, and a provisional member of the editorial board of the Zionist Tagblatt in Lvov. He spoke to his wife only in Hebrew. 5) Henryk Lilien, a Doctor of Philosophy, a teacher in the government gymnasiums, and later the first principal of the Jewish gymnasium in Lvov in the year 1919. 6) Josef Silberman, a Doctor of Jurisprudence and lawyer. 7) Arje Verständig [Ferstendig], a Doctor of Jurisprudence and lawyer. 8) Leo Lauterbach, a Doctor of Jurisprudence, a member of the leadership of the Academic Zionist Organization (A.Z.), and later the general secretary of the leadership committee of the World Zionist Organization and director of its organizational committee. He was the author of a family tree covering 8 generations of the Lauterbach family, a book that won wide acclaim. 9) Dawid Margulies, an engineer. 10) Yaakov Nadel-Frost, in the United States. 11) Dov Knopf, currently Nitzani, a Doctor of Jurisprudence and a lawyer, a member of the leadership of the Academic Zionist Organization, member of the people's council in Przemyśl in 1918-19, a Zionist activist in the Diaspora. 12) Herman Reif, Doctor of Jurisprudence and a lawyer.

|

|

Agudat Herzl before 1914 Standing from left to right: Leo Minz [Münz], Landau, Friesel, Kupfer, Ludwik Minz [Münz], Pömstein, Herschdörfer, Klugman, and Fried Sitting: Reif, Lauterbach, Halpern, Duldig, Rosenfeld, Knopf-Nitzani, Pasternak, Eisner, Gottfried |

[Page 97]

It is appropriate to mention Leo Frachtenberg, a professor of dialects of Indian languages in a university in the United States. He accompanied Professor Weizmann on his first major publicity tour of the United States after the First World War. He was one of the first founders of the Zionist groups in the gymnasium of Przemyśl. He left Przemyśl in 1904 after completing his matriculation exams and immigrated to the United States, where his parents lived. While still in the gymnasium he was one of the initiators of the Academic Zionist Organization in Przemyśl following the matriculation exams of his year, but he was not around to participate in its founding.

It is hard to even dream of a larger group in Przemyśl. The atmosphere that pervaded in that city, particularly among the Jewish intelligentsia, was definitively non-Zionist in those days. The older generation of the intelligentsia were involved, more or less, with assimilationist ideas. They did not even have a small group of supporters of Zionism. The middle generation turned partly to Socialism, while another portion saw its world view as nihilist political radicalism. This was generally a passive, and even somewhat negative, element with respect to nationalism. Only few affiliated with nationalistic Judaism. Most of these were natives of other cities who were law candidates, and were doing their articling in the city. From among the younger generation of academics, there were very few serious assimilationists, but there were also very few Zionists. Most of this stratum of youth was neutral with respect to nationalistic Judaism, which demanded nothing of them. In the years before the Herzl organization, this stratum of youth mostly conducted literary events, some of which were connected to Jewish issues. However, all of this was done with ideas of neutrality.

The new organization, which was founded at the time of the great awakening to Zionism in the wake of the death of Herzl (to which the name of the organization is linked) developed slowly during its first years. Its number of members did not grow significantly, and its influence and authority did not grow in the city. However, with the passage of time, starting from 1910, after a break during the years of 1908 and 1909, a new stratum of youth came from the universities (and not directly from the high school graduates), who were educated in the student corporations mainly in Vienna and Lvov, where they practiced fencing. This youth was filled with energy and a spirit of enthusiasm, even though their ideas were not always sufficiently refined. They attracted the elder strata after them, who were discrete but more mature in their ideas. They injected new life into the organization, which grew in membership. They particularly influenced its internal life. Daily meetings (“buda” in the vernacular) were held in the fine hall of the organization. There was song, joyous parties, albeit solidity, over a glass of beer (“knaipe” in the vernacular)[a], honest friendship, educational work to deepen the ideal, testing of the youth, classes and internal lectures. Zionist lecturers and preachers were invited to the broader community. (In this area, it is worthwhile to mention the lectures of Shlomo Schiller, Boris Shatz, Shmaryahu Lewin, and Nachum Sokolov.) There were annual public festivities, the income of which was dedicated to nationalist causes, the “Betzalel” exhibition, etc.

The organization became an attractive force, and the number of students who joined it increased annually. Among them were those who in whom great hopes were placed from an ideological and moral perspective. This was already the third stratum, which was a blend and continuation of the first two strata: there was a blend of ideological awareness, and faith in the power of the movement and the role of the organization. The three strata existed together a life of brotherhood and unity: The Herzl Organization served as an example of an academic organization, in which eight and later ten classes of intelligentsia joined together. The members of the organization would meet together daily for the “buda” and wove together happy communal life with love of a common ideal. Even the elders (“alter herr”) did not see themselves as exempt from work for the organization, even though this was permissible according to the charter. Starting from 1910, the organization found itself in an unceasing stream of development. Abraham Sonne influenced the ideological direction and mode or operation of the Herzl organization.

[Page 98]

Already by 1911 and 1912, the Herzl organization had won for itself recognition and authority in the city. This raised the status of Zionism, which had been in a depressed state in the city. The Zion Organization disappeared and was forgotten, but Zionism lived in the city, was felt there, and the pleasant fluttering of its wings was heard in the air. Wide circles of people participated in the events of the Herzl Organization. It is appropriate to mention here the lecture of Shmaryahu Lewin in the hall of the city hall. Not only was the hall filled to the brim with those invited, but furthermore large groups of people who did not succeed in obtaining entry tickets stood outside on all sides of the building. The giant hall of the workers organization was also filled to the brim during the lecture of Nachum Sokolov. Not only was the excellent functioning of the organization felt, but the signs of the times were also seen there. Then it was already appropriate to be a Zionist in Przemyśl. The dream of the youths of those days, while they were still wearing their gymnasium uniforms, took on a physical form.

The exhibition of products of Betzalel in 1912 was an event of great value. It lasted for an entire week, and brought financial and moral attainments. The exemplary organization and dedication of the youth (especially the academics and the females) brought the desired results. It is fitting to specially praise the organizer of most of these activities, Leo Landau, who already then displayed his organizational talents that later were to become evident in his communal work. The participation of women, who were organized starting from 1904 in the Hadassah Zionist organization, in the Betzalel exhibition should be remembered for good. Hadassah was an organization of young women who were noted for their astuteness. The first chairwoman was Chawa Krebs. Members included the Bruss sisters, Ernestina Rinde (later a rebbetzin in Lvov), Roza Reif, Czarna Kerner, Mrs. Melon who married the communal activist Hacke and succeeded in making aliya and living in Israel on agriculture, and many others. This organization was not able to last long or last in an uninterrupted fashion. An organization for older women arose after the First World War, whose members consisted primarily of women of important communal status.

The Herzl Organization won renown among the Zionist youth of Galicia, despite the fact that most of its efforts were directed internally, without any publicity in newspapers. There were times of crisis for the Zionist youth of that area. After the times of flourishing and enthusiasm came an era of decline. Despite the increase in membership, the ideal became weakened. As a result of the crisis, a convention of the Zionist youth of Galicia was arranged in 1912 in Drohobycz. At that convention, a national organization was founded called the A.Z. (Organization of Academic Zionists). Its leadership was given to three members of the Herzl Organization. With this, the convention expressed its faith in this corporation. The Herzl Organization did not betray this trust. The three semesters of the Przemyśl leadership of the A.Z. strengthened the idealism and organization level of this new national organization. The leadership was conducted without fanfare, but with success. It succeeded in its activities due to the technical and financial help of the Herzl Organization. It is appropriate to mention the meeting of the leaders of the Zionist academic organizations in the beginning of 1913, and the splendid annual convention in the autumn of 1913, both in Przemyśl. The amount of circulars, minutes and correspondence was increased by the cooperation. The Herzl Organization also helped with the expenditures for the publication of the pamphlet of Dr. A. Lauterbach, “The Role of the Zionist Youth” in the summer of 1914. These were the finest pages in the annals of the organization before the First World War.

The war not only interrupted the development of the A.Z. but the activities of the Herzl Organization were also silenced then. However, the communal basis was already well founded. We should not be surprised that the war did not succeed in destroying it, and the organization continued after the war with a meeting of its members in Vienna and Przemyśl, and through the exchange of correspondence among those who were dispersed throughout Austria. The activities of the Herzl Organization resumed in the autumn of 1918. The number of its members grew and the influence on the youth increased through a merger with the young Yehudia Corporation that was founded in the interim. It once again became an important influence on the Zionist intelligentsia of the city and the country.

[Page 99]

With all the merit and acclaim that this organization accumulated, we cannot conclude this chapter on the annals of the Herzl Organization without mentioning the first excellent chaluzim (Zionist pioneers) of the organization. In the first rank were Dr. Tzvi Luft, Samson Goldstein, and Dr. David Zak [Scheck?]. As well, we must mention the following members of the semesters that followed the founders: 1) Pinchas Kupfer, a Doctor of Jurisprudence and a lawyer, a member of the leadership of the A.Z.; 2) the pleasant Yehoshua Hershdörfer, a physician, who settled in Kraków and worked there as a Zionist activist, a physician and artist, and was also involved in fine literature. 3) Leo Duldig, a Doctor of Jurisprudence and lawyer, a member of the second presidency of the A.Z. 4) Jakob Rebhan, a physician, whose Łuck soured. He was the last head of the community of Przemyśl and fell in the line of duty. 5) May he live long, Leo Landau, a Doctor of Jurisprudence, the excellent organizer of the community and activist on the communal council of Vienna, who served, among other roles, as the chairman of the organization of synagogues of Vienna and the director of social assistance in the community.

The activities of the Herzl Organization were interrupted from 1921-1925, however the chain was not broken. In April 1925, that new generation of enthusiastic youths was renewed, and it continued in its wonderful tradition until the destruction of Jewish Przemyśl. This will be described in the Section Three.

|

|

The H.A.Z. conference in Przemyśl in October, 1913 Sitting from left to right: A. Sonne, Dr. P. Kupfer, Dr. L. Lauterbach, Dr. S. Rosenfeld, Dr. I. Schwartzbart, Z. Horowitz, Dr. D. Knopf, Dr. L. Duldig |

Original Footnote:

Translator's Footnotes:

Coordinator's Footnote:

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Przemyśl, Poland

Przemyśl, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 22 Aug 2025 by LA