|

56°33' / 27°43'

Translation of “Ludza” chapter

from Pinkas Hakehillot Latvia v'Estonia

Written by: Dov Levin

Published by Yad Vashem

Published in Jerusalem, 1988

Acknowledgments

Our sincere appreciation to Yad Vashem

for permission to put this material on the JewishGen web site.

This is a translation from: Pinkas Hakehillot Latvia and Estonia:

Encyclopedia of Jewish Communities, Latvia and Estonia,

Edited by Dov Levin, published by Yad Vashem, Jerusalem (pages 160-167).

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

[Page 160]

(German: Ludzen, Russian: Люцин, called by Jews: Lutzin)

Translated by Jerrold Landau

Donated by Anonymous in Denver

Translation first published in Latvia SIG, vol. 3, no. 2, June 1998

It is a regional city in the north–east of Latgale, 100 kilometers north–east of Daugavpils, in a district rich in lakes.

| Year | General Population (number) |

Jewish Population (percent) |

Percentage |

| 1772 | 227 | 66 | 34 |

| 1802 | –– | 582 * | –– |

| 1815 | 1,800 | 1,175 | 67 |

| 1847 | –– | 2,299 | –– |

| 1868 | 3,578 | 1,915 | 55 |

| 1897 | 5,140 | 2,802 | 55 |

| 1900 | 6,000 | Approx. 3,000 | Approx. 50 |

| 1914 | 7,100 | Approx. 3,500 | Approx. 50 |

| 1920 | 5,044 | 2,050 | 41 |

| 1925 | 5,559 | 1,907 | 34 |

| 1930 | 5,359 | 1,634 | 30 |

| 1935 | 5,546 | 1,518 | 27 |

Until the End of the First World War

History of the City

Ludza was conquered in the 13th century by the Livonian Order, which built a fortified castle there. It passed to Poland in 1660. It was under Russian rule from 1772 and onward. In 1802, it became a regional city in the District of Vitebsk. Its connection to the railway line in the 1890s hastened its development as a district regional center. It was granted the status of a city in the year 1895.

The Founding of the Community and Demographic and Economic Development

According to the tradition that was accepted by the elders of the Jews of Ludza, a small Jewish community already existed there in the 16th century. When Czar Ivan the Terrible conquered Pulutsk and other cities in White Russia in 1577, and ordered that the Jews be drowned in the river – according to tradition, the Jews of Ludza escaped before the city fell into hands of the soldiers of the Czar. Thus, they were saved from the fate of their brethren in the conquered cities. After the king of Poland, Stefan Batory reconquered the district of Lutzin in the year 1582, Jews returned to settle in the city and its environs. In any case, we have no information of the continuity of the existence of the community in the 17th century.

One of the first pieces of information about the community during the 1760s is based on the existence of a stone monument in the old cemetery. This monument is over the grave of the tailor Moshe the son of David, who earned his livelihood from fixing the clothing of the farmers the neighboring villages. Once, the tailor became entangled in a religious debate with a farmer. The farmer libeled him to the owner of the estate for uttering words of denigration regarding their messiah. The owner of the estate, a zealous Catholic, ordered in his stubbornness that Moshe the son of David be arrested, and he commanded him to convert, so that his sin could be forgiven. If not, he would be burnt to death. The tailor refused to change his religion, and was burnt at the stake. Etched on the stone is: “And all of Israel shall bewail the burning…”[1]. The martyr Moshe the son of David, 5 Tammuz 5525 (1768)[2].

The large growth of the community during the first half of the 19th century was influenced by the expulsion of the Jews from the villages and estates, and the ban imposed on them from owning inns. However, along with this, it seems that the economic distress in Ludza caused several Jewish families to immigrate in 1835 to the districts of Kherson and Ekaterinoslav, where Jewish agricultural settlements were being established at that time. Tens of additional families of Ludza set out to the settlements in the years 1846–1848, as well as during the 1850s. In total, their number reached 50. The exodus took place in an orderly fashion. One of the groups took along a Torah scroll. As a result of this emigration, the population of the community dropped from 2,299 in 1847 to 1,915 in 1868. A possible additional reason for the shrinkage of the community during those years is the fire that broke out Ludza in 1866 and destroyed about half of the houses of the city.

The Jews of Ludza earned their livelihoods at that time primarily from the trade of agricultural products, such as lumber, grain, and flax. No small number were also involved in agriculture. At the end of the 19th century, two agricultural settlements were founded on government lands near the city. A survey of tradesmen in the city that took place in the 1880 by the AYK”A Society shows that 71 of 104 trade workshops were Jews. In total, there were 310 Jewish tradesmen, and 62 dayworkers. More than 40% of the tradesmen were tailors.

During the 1840s, the tradesmen set up a mutual aid organization called Poalei Tzedek. At the same period of time, the community set up a charitable fund that granted loans to retail merchants, especially peddlers who made the rounds to the villages with their merchandise. During the early 1880s, which were years of famine in Russia, the community operated a special assistance organization that baked bread and sold it to the poor at half price. Such charitable operations, and other similar ones, arose on occasion during times of difficulty and operated in addition to the existing charitable institutions such as Bikkur Cholim (organization for the visiting of the sick), and Hachnasat Kallah (organization for providing for poor brides).

Displays of Anti–Semitism

During the 1880s, several significant anti–Semitic incidents took place in the city. In the spring of 1883, a Christian maid who worked in the home of a Jewish family named Lutzov disappeared. After her body was discovered in a pool of water outside the city, the members of the Christian clergy quickly spread a story that the maid had apparently been strangled in the home of Zimel Lutzov by family members, and her blood was drawn for the baking of matzos for all the Jews of the city. Thus, an accusation was laid against the entire community.

[Page 161]

Anti–Semitic newspapers spread news of the libel throughout Russia. A well–known lawyer from Peterburg defended the Lutzov family members in court. He succeeded in disproving the words of the false witnesses presented by the prosecution. The adjured judges, chosen from amongst the residents of the city and its surrounding area, unanimously exonerated the accused. “The Jews of Lutzin were justified, and were glad and joyous” wrote Hamelitz in an article devoted to this topic (April 22, 1885). A short time later, the general prosecutor appealed the verdict in front of the supreme court in the district city of Vitebsk. Great pressure was exerted upon the judges by the government prosecutor and members of the clergy to find the accused guilty. Zimel Lutzov was sentenced to life imprisonment, and his wife to six years of prison.

A new supervisor appointed to the local government hospital at the beginning of the 1880s immediately fired the Jewish physician, openly stating that “It is preferable that a Jewish physician not be found in a public hospital.” The number of Jewish students accepted in the public school was restricted by order of the authorities.

|

|

Institutions and Communal Life

Rabbis: From almost its beginning, the community of Ludza became known as a large locale of Torah and studiers of Torah. It was the place of nurturing and location of tenure of rabbis and Gaonim, who, along with their descendants, became known for generation after generation.

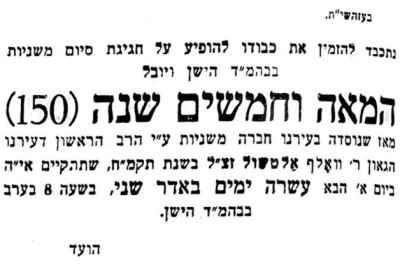

The first of the rabbis of the community was apparently rabbi Zev–Wolf Altschuler, who settled in the city in the year 1786. Two years later, a Chevra Mishnayos [Mishnah study group] was founded there, which existed continuously for 150 years, until the Holocaust. Rabbi Altschuler, who died in 1806, authored several books of commentary (Sfat Hayam, Even Pina, and others). Following Rabbi Altschuler, Rabbi David Zioni, the head of a dynasty of rabbis of that family, occupied the rabbinic seat. (When the law obligating the use of family names went into effect, Rabbi David chose that name.) When Rabbi David died in his prime (in 1810, at the age of 48), his eldest son, Rabbi Naftali Zioni, inherited his position. He lived long, and served in his position for 46 years. When the censor law went into effect in Russia, Rabbi Naftali Zioni was appointed as the censor in Ludza for sacred and secular books. After his death in 1856, his son, Rabbi Aharon Zelig Zioni, was invited to occupy the vacant position. Like his father, Rabbi Aharon Zelig was known for strongly standing beside the youth of poor families who were snatched for service in the Czar's army in place of the sons of the wealthy and well–to–do. With money that he made efforts to raise, he would redeem the poor, Torah studying lads, who had been forced to fill the quota of draftees to the army imposed upon the community. Rabbi Aharon Zelig served in his position in Ludza for 20 years (1856–1876). After his death, his home was turned into a synagogue. His book of responsa was published in 1975 with the title of Sefer Zioni.

During the long tenure of Rabbi Naftali and his son Aharon Zelig, the community consolidated with the force of their deep traditional influence, their proper, just conduct, and their protection and mutual pleasantness. An event that took place in 1866 testifies to this. An elderly Jew from a far–off city, Izik Chaim Bandarski, appeared before the heads of the community and demanded reparations for being caught, along with three friends, as they were working for a Jewish contractor in the area 34 years previous. Since they did not have their certificates of citizenship with them, they were taken by force to serve in the army in the place of Ludza natives who were to be drafted. The Jewish accuser claimed that Rabbi Naftali Zioni redeemed and freed his friends, but did not manage to redeem him. Therefore, he was forced to serve in the army of the Czar for many years in place of the son of one of the wealthy members of the community. The rabbis of the city and heads of the community recognized the correctness of the claim of this man, and allocated a significant sum of reparations for him. This story of this situation and the memory of the words from the adjudication and verdict, with the signature of the accuser, were recorded in the ledgers of the Old Beis Midrash as follows: “I, the person signing below, Izik the son of Reb Avraham Abba Bandarski, who was taken by the people of Lutzin to Feimanka to army service in 1854 – I have now come to Lutzin and agreed with them on the sum of 75 rubles to forgive them completely and decisively from the depths of my heart. I have no further complaint against them, nor do I hold any grudge in my heart. I forgive those who were there at the time, whether they have already died or are still alive. All this was conducted with a handshake and a formal agreement. I have signed on Tammuz 24, 5646 (1886). Signed, Izik Chaim Bandarski.”

Following Aharon Zelig Zioni, his brother–in–law, Rabbi Eliezer the son of Shabtai–Don Yachya, sat on the rabbinical chair[3]. He was the scion of a dynasty of rabbis, great in halacha, writers and poets, descendants of an old family who had come from Spain. The name of Rabbi Eliezer spread throughout Russia as an expert in decisions of Jewish law. Rabbi Kook studied Torah from him in Ludza during his youth. The Christian residents of the city also honored him, and turned to him to adjudicate their disputes. From his youth, he was enthused by the ideas of settling the land and Zionism. His work Even

[Page 162]

Shetiya was published in 5653 (1893), and his other work Taam Megadim was published posthumously in the Shoer Family Publishing House of Ludza.

The fact that a native of Ludza, the merchant and maskil Yekutiel Ziskind Levi, was chosen as one of the two delegates from the region of Vitebsk to the convention of Jewish delegates of Western Russia that took place in Vilna in 1818, testifies to the status of the community. That wealthy man, Y. Z. Levin, built a large, two–story house in the center of the city in 1880, which was one of the first stone buildings in the city. The wide–branched family of the wealthy man lived there, including his sons and descendants, generation after generation. The businesses of the family members were located on the ground floor. The residents of this stone house, all of whom were related, as has already been noted, were called di moyerer by the community, that is “people of the stone house.” They also had their own synagogue.

Educational, political, and social activities: Secular education under the auspices of the community began in the year 1865 with the founding of the private boys school. 62 students studied there during its first year. That year, a Talmud Torah was set up in the traditional style. Through the efforts and funding of several wealthy members of the community, an additional Talmud Torah was set up in 1887, which also taught general subjects such as Russian and arithmetic. The community funded its upkeep from the meat tax (Korobka). 40 students studied there in the year it was founded.

During the 1890s, the teacher Yafeh founded a private school for boys. Later, in 1910, a private Hebrew school was opened in the form of a modern cheder. It was founded by the teacher Meir Levin and the writer Hirsch Malamud. They imparted love of Zion and the Hebrew language in the heart of their students. This first Hebrew school, in which 60 students studied, only operated for two years. At that time, approximately 50 Jewish students studied in the public schools of the city.

In 1883, Chaim Shoer, a member of the Zioni rabbinical family, opened a bookstore in Ludza. The store also turned into a lending library after a short time. In 1907, the owner of the store and the library founded the first and only Jewish printing press in Latgale.

Starting from the 1850s, several known personalities from the community made aliya to the Land, including Rabbi Yaakov Zeev, the brother–in–law of Rabbi David Zioni. The latter made aliya at the end of the century and settled in Hebron. He visited Ludza several times as an emissary of the Rabbi Meir Baal HaNes charity. During the time of the Bilu aliya in the 1880s, and in the spirit of Hibbat Zion, David Yehoshua Levin and his family of six made aliya among the others. Several family members preceded the family in aliya. During the years before the world war, a local branch of Poalei Zion was set up in Ludza.

The winds in the city were not helped by the members of Bund, who attempted to arouse social unrest in the city. Nevertheless, they succeeded in instigating a strike in several Jewish owned workshops in 1904–1905. The owners of the workshops requested the intervention of the police, who arrested several of the strikers. Meir Levin stood at the head of the open and clandestine Bund activity in Ludza during those years. He was forced to leave the city because he was liable for imprisonment. When he returned to the city several years later, there was not one member of Bund around. As mentioned above, Meir Levin founded a Hebrew school in the community. He made aliya at the end of his life.

During the First World War

During the war, hundreds of Jews left the city and moved to the interior of Russia. In their place, hundreds of Jewish war refugees from western Latvia and Lithuania found refuge in Ludza. Some were relatives of residents who preferred to endure the war under the same roof as their relatives over wandering far from their homes and communities. Students of the Yeshiva of Rabbi Yitzchak Yaakov Rabinovitz (Rabbi Itzele Ponivicher) were among the refugees who arrived from Lithuania. By the end of 1915, the number of Jewish refugees in Ludza reached approximately 2,000. The central committee for the assistance of Jewish refugees in Peterburg provided help with food and money. The aid services in the community, which ceased activity due to the departure of the communal activists, were reorganized, and offered aid to the war refugees in the city and area. The rabbi and Yeshiva lads left Ludza in 1917, when the Germans were about to conquer the city. During the years of 1918–1919, the city passed from hand to hand at times. Most of the houses of the city were destroyed or damaged. The Jews of Lomza endured days of fear and serious deprivation during the time of the Bolshevik rule, from the end of December 1919 until January 26, 1920, the day when the city was conquered by the Latvian national army. A Jew named Levin, the son of a known family in the community, served as police chief during the Bolshevik period. During his tenure, Levin issued an edict obligating the Jews to open their stores on the Sabbath. Of course, this caused great distress. The local rabbi at that time, Ben Zion Don–Yachya, stood in the office of the police chief, and, as was said, spoke sharp words to him, and mentioned the verse, “I have raised and brought up children”[4]. In this fashion or another, the rabbi influenced the police chief to annul the decree.

Between the Two World Wars

Demographics, Economy, and Society

The war refugees began to return from Russia in the spring of 1920. At the end of that year, the community numbered more than 2,000 individuals, approximately 60% of its pre–1914 numbers. Approximately one third of the Jews of the community, primarily the refugees who returned lacking everything, required urgent assistance. Another third earned its livelihood in a meager fashion, and they also awaited assistance and general rehabilitation. The JOINT provide quick effective aid to both groups.

[Page 163]

In collaboration with the communal council that was chosen anew in the autumn of 1920, the JOINT also allocated sums of money for the communal institutions for various goals, such as renovating the communal buildings, rehabilitating communal services, first and foremost – health services. One of the most important institutions set up at that time was the Jewish loan and savings fund (Ludzer Yiddishe Lei Und Shpar Kassa). The JOINT assisted the renovation of many of the 282 Jewish homes that were damaged during the war. The Jewish population dropped by a quarter (from 2,048 to 1,225) from 1820 until 1933[5].

Thanks to the broadening of commercial connections during the 1820s between Latvia and the Soviet Union, which was in urgent need of flour and grain, these areas of commerce began to flourish in Ludza, for Ludza was one of the primary centers of distribution of those products. However, in 1924, the Soviet Union suddenly canceled the commercial agreement, causing a serious recession in the city, which barely had any manufacturing enterprises. The business recession lead to unemployment. Over and above all this, there were two years of poor agricultural crops at that time. The impoverishment of the farmers again affected the Jewish merchants and shopkeepers. The lending and savings fund, which had 167 shareholders in 1923, was unable to respond to the urgent needs of the merchants. Many merchants were forced to turn to the local branch of the Latvian national bank; however, the its loans were given in an illegal fashion with gouging interest rates. Within a short time, this led to a wave of bankruptcies among the loan recipients. The matter was brought to adjudication in the economic and budget committees of the Latvian parliament (Saeima). Through the efforts of the Jewish members of the Saeima, a parliamentary investigation committee was established, which brought government intervention with the goal of preventing the destruction of the economic status of the Jewish merchants, and of commerce in the city in general. The situation of the Jewish tradesmen was also not firm. Their numbers were about 100 during the 1920s. The shoemakers organized into a cooperative, that also dealt with the problem of unemployment in that sector.

Based on data received from the population census of 1935, there were 302 first–class shops and businesses in the city, of which 191 were owned by Jews. Details are as follows:

| Sector or Business Type | Total | Jewish Owned | |

| Number | Percent | ||

| Grocery | 53 | 48 | 90 |

| Bakeries, bread and flour shops | 19 | 15 | 79 |

| Inns and taverns | 17 | 5 | 29 |

| Bookstores | 3 | 2 | 67 |

| Butcher shops | 11 | 7 | 64 |

| Drink and sweets shops | 11 | 8 | 73 |

| Clothing and textile shops | 32 | 31 | 97 |

| Shoe stores | 21 | 20 | 95 |

| Medicine and chemical shops | 4 | 4 | 100 |

| Pharmacies | 3 | 3 | 100 |

| Furniture and household goods shops | 5 | 4 | 80 |

| Haberdashery | 4 | 4 | 100 |

| Agricultural supplies and metal implements | 19 | 16 | 85 |

| Watchmakers | 3 | 3 | 100 |

| Building materials and paint | 5 | 4 | 80 |

| Wheat | 7 | 6 | 90 |

| Barber shops | 8 | 6 | 75 |

| Various | 5 | 5 | 100 |

From among the free professions, three of the six physicians in Ludza were Jews. The three dentists were also Jews.

The great fire of June 12, 1930 caused general ruin affected the city and its Jewish inhabitants. 212 houses and 117 businesses went up in flames, 95% of which were Jewish owned. Among the rest, the Old Beis Midrash and old stone house, the Catholic church, government offices, and two Jewish owned bookstores were burnt down. The neighboring communities provided urgent aid to 140 families, some of whom were left with nothing. Some of them had lost their homes in the fire. The Jewish institutions in the capital city participated in the rehabilitation of the shops and workshops. The Latvian government budgeted a significant sum of money for rehabilitation, and tasked the interior minister with dealing with the technicalities of rehabilitating the ruined quarter. The office of the loan and savings fund, which at the time had 290 shareholder members, went up in flames in the fire. The valuable papers and money of the fund were not damaged, so it was able to continue its activities and assist those who were affected by the fire. The fund granted 1,575 loans in 1938.

The Community and its Institutions

For many years, the communal functionaries Nathan Levin, Sh. Ostnovski, and Aharon Dov–Ber Gamzo, a devotee of the Revisionist Movement and a member of the city council of that party, stood at the head of the community. The communal council included the aid institutions and various charitable funds in its realm of operations. During the 1920s, the Bikur Cholim society split into two separate organizations, one for the Hassidim and one for the Misnagdim. However, it was not long before the two organizations reunited. An orphanage was set up in Ludza immediately after the war through the efforts of the activists of the leftist Arbeiter Heim union, who obtained funding from the United States. That institution only lasted for several years.

Religion: During the period of Latvian independence, there were seven synagogues in the city, most of which were centered around “Di Shul Hoif” – the courtyard

[Page 164]

of the synagogues, near the lake. They were as follows: 1) The central synagogue, the oldest of them. “The Shul” was built in 1804. Its holy ark was decorated with wood etchings engraved by an artist; 2) the Green Beis Midrash (Der Griner Beis Midrash); 3) The Old Beis Midrash (Der Alter Beis Midrash), built in 1829; 4) The Minyan of the Hassidim, built in 1827; 5) The Synagogue of the Rabbi, established in 1876 in the house of Rabbi Aharon Zelig Zeligman, following his death; 6) the Minyan in the Stone House, burnt down in 1938; 7) The house of worship in Slobodka, in the north of the city.

During the first post–war years, Rabbi Eliezer Don–Yachya continued to sit on the rabbinical seat. After his death in 1926, his son, Rabbi Ben–Zion Don–Yachya, took his place. He was one of the activists of the Mizrachi movement in Latvia. Rabbi Ben–Zion Don–Yachya served until the destruction of the Jewish community of Ludza. He perished in the Holocaust along with his community. Rabbi Don–Yachya wrote the book Yachas Avot, describing the family tree of his family in Ludza and in other communities; a series of historical surveys; and the Torah work on Shulchan Aruch – Orach Chaim (two volumes of which were published, and one was lost during the war). His son Shabtai Don–Yachya served as the editor of the Hatzofeh newspaper in Israel for many years.

Eliezer the son of David Zeligman, the grandson of Rabbi Naftali Zioni, was one of the great scholars of the community. Aside from his Torah works, E. Zeligman wrote Megilat Yuchsin – a work that includes the family history of the old, venerable families of Ludza: the Altschuler, Zioni, Zeligman, Don–Yachya, Levin, and other families.

|

|

| Rabbi Ben–Zion Don–Yachya served in the rabbinate of the community of Viļaka (Marienhausen) from 1902–1928, and following that, in the community of Lutzin until he was murdered in the autumn of 1941 along with his community. |

|

|

| The funeral Rabbi Eliezer Don–Yachya in Ludza (Lutzin), 1926 |

Education: Almost all the children of the community studied in the Hebrew public school founded in 1918. “The Hebrew public school of Ludza has a good teaching staff , and exceptionally good equipment.” – Thus was written in an report of the JOINT regarding the educational institutions at the beginning of the 1920s. In 1922, the local Russian gymnasia, in which 80% of the students were Jewish, turned into the city Jewish gymnasia. The students of this school

[Page 165]

set up a mutual fund to pay tuition. At the beginning of the 1920s, there was an educational institution, a form of modern cheder, which also taught general subjects.

A large cohort of Hebrew teachers emanated from the community of Ludza. They also taught in other communities. Most of the youth were fluent in the Hebrew language thanks to the Hebrew school and its teaching staff. The Hebrew teacher Yechiel Shuval (former surname was Shavlov) earned the praise of Shaul Tchernichovsky in 1930 for succeeding to obtain 40 subscriptions for the books published by Shtibel. Shuval and his brothers Berl and Nisan Shuval founded a Hebrew library and established an organization for Hebrew speakers called Safa Chaya (Living Language). In this manner, they won over the hearts of the local youth to Hebrew and Zionism. They even convinced their father, a teacher with his own cheder, to adopt the “Hebrew in Hebrew” teaching methodology. When Ch. N. Bialik visited Latvia in 1931, he went to Ludza to witness the success of this small community, which attained fame on account of its rabbis and teachers.

Factions and Organizations: Even though the population of the community declined in number, there was no weakening of communal life and activity. Parties operated at that time, and pioneering youth movements, such as Hashomer Hatzair – Netza'ch, Gordonia, Borochov Youth, and Herzliya were founded. Ludza was one of the strongholds of the Beitar and Revisionist (Hatzaha'r) parties. The visit of Zeev Jabotinsky to the city in 1923 left a strong impression. With the passage of years, the strength of the Young Zion party (from the 1930s, the Young Zion – Hitachdut party) continued to grow. Its meeting place was a center for cultural activities. On the other hand, the significance of the Bund declined, as it no longer attracted many of the youth to its Y. L. Peretz hall. A group of Jewish youth was active in the clandestine Communist youth cells. In the elections to the Saeima in 1925, the Bund list in Ludza received 330 votes as opposed to the 275 votes given to Young Zion. However, in the elections of 1928, more than half of the Jewish votes in the district of Ludza were given to Young Zion – 1,077, as opposed to 663 for Bund and 365 to Agudas Yisroel. Of the 20 members elected to the city council in 1925, eight were Jews: five from the Zionist block list, and three from the Bund. In the elections of 1928, the Zionist block again received five delegates, whereas the Democratic block of the Bund and the leftists received only two delegates. The delegate of the merchants was also Jewish, so the total number of Jewish delegates did not decline. Nathan Levin served as the vice mayor for many years.

We can understand the political and ideological composition of the Zionist camp in Ludza from the results of the elections for the Zionist congresses:

| Congress | Year | General Zionist List |

Young Zion, Socialist Zionists |

Revisionists (Hatzaha'r) |

Mizrachi | Total number of voters |

| 14th | 1925 | 18 | –– | 55 | –– | 72 |

| 15th | 1927 | 19 | 33 | 141 | 8 | 201 |

| 16th | 1929 | 25 | 40 | 120 | 9 | 194 |

| 17th | 1931 | 22 | 71 | 104 | 9 | 206 |

| 18th | 1933 | 48 | 210 | 196 | –– | 454 |

During and After the Second World War

During the Time of Soviet Rule (1940–1941)

Many of the businesses of the city were nationalized in the general political rubric of the new regime. The political and cultural organizations, and educational and aid institutions, were gradually closed by edict of the government. On September 9, 1940, a command was issued to close one of the charitable institutions. The directorship was tasked with completing the liquidation process within two months from the issue of the edict. Someone named Y. Zbrowski was appointed as the person responsible for closing the institution. Several Jewish families were exiled to Siberia on June 14, 1941. The family of one of the local heads of the community and revisionist leader, Aharon–Yissachar–Ber Gamzo, was among them. He perished in a Soviet labor camp.

The war between Germany and the Soviet Union broke out one week after the exile. Relative quiet pervaded in the city and its environs during the first days. Jewish refugees from Lithuania and various parts of Latvia began to arrive. They waited at the railway station for the opening of the old Soviet border, and the Jews of Ludza helped them and provided them with food. As the front approached Ludza, the Jews of Ludza deliberated over the question as to whether to escape eastward in the direction of Russia, or to remain in place. Several of them asked the rabbi of the community, Rabbi Ben–Zion Don–Yachya, to leave the city, and also to influence other Jews to escape. However, there was no reason to escape in the opinion of the rabbi, and he refused to accede to the request. The border was opened during the last days of June. Many of the refugees and hundreds of Jews of Ludza succeeded in reaching the interior of the Soviet Union. Some of the Jewish youth of Ludza fought and fell in the ranks of the Red Army. One of them, a captain of the patrol named Tomaszinski, earned the Alexander Nievski decoration of bravery.

Under Nazi Occupation

The German Army conquered Ludza on July 3, 1941. The persecution of the Jews began immediately after the conquest. There were incidents of theft and pillage, expulsion from homes, libels, and murders of individuals and family. On July 5, approximately 50 Jewish refugees who were in Ludza at that time were arrested, and 12 of them were taken out to be killed. The Jews of Ludza

[Page 166]

were forbidden from burying them, and their bodies were tossed into pits. On July 20, an edict was issued to form the ghetto. Bruno Zaver was appointed as chief of the ghetto. Two Latvians, Viktor Ladoson and Pavel Kobraski, served as his assistants. A narrow area between several forsaken streets at the edge of the city was designated for the ghetto. Thousands of Jews of Ludza, as well as Jews who arrived from the nearby villages, were crowded into this area with great cramping, up to 18 people in one room.

Several hundreds of men were gathered into the two synagogues. A series of decrees was imposed upon the Jews: the obligation to wear a yellow patch on the chest and the back; the ban on walking on the sidewalks; harsh labor; and small food rations. Jewish girls were taken from the ghetto to fulfil the lusts of the Latvian and German guards. They were raped, and some were subsequently killed. A short time after the establishment of the ghetto, a group of 35 older people, and people unfit for work were taken out at the command of the head. They were hauled to an area outside the city and killed by shooting in the building that had formerly been a rope factory. According to several versions, Rabbi Ben–Zion Don–Yachya was among those who perished there.

On August 17, 1941, the majority of the Jews of the ghetto were taken (the sick and elderly were transported on trucks and wagons) and killed by shooting at the shore of Lake Curba, about seven kilometers from the city. Before they were murdered, thy were all gathered not far from the pits and ordered to remove their clothes and give over their valuables. The killing was carried out by units of the security police under the command of a German captain who arrived specially in Ludza, and with the assistance of local Latvian police who secured the area and also participated in the slaughter itself. There were approximately 800 victims. Men, women, and children were murdered. Their bodies were buried in two burial pits, 20 meters by 3 meters in dimension. On the evening of the bloody day, the drunk murderers returned to the city on trucks laden with the property of the victims, including clothing, baby carriages, and valuables.

After this aktion, several hundred Jews, consisting of those who worked for the Germans and their family members, remained in Ludza. On August 27, 1941, approximately 120 Jews were taken to be murdered, including entire families. Among them were 40 young women who worked in the German military hospital, and Jewish war refugees from Riga, Daugavpils (Dvinsk), and Rēzekne (see entry). Three young Jewesses were removed from the place of slaughter by the German army captains. They were returned to the ghetto a few days later, and murdered later on. On October 27, 1941, 120 additional Jews were removed from the ghetto. They were transported in rafts to Daugavpils, and from there to Rēzekne, where they were murdered. After the three slaughters (aktions), 25 Jewish professionals remained there, with some family members. These final survivors were murdered on May 2, 1942 in the Gorbrovski Forest near the city. Of all Ludza Jewry, one three–person family and one woman survived, having found refuge with a local Polish resident, as well as a Jewish female baby. The baby fell from a wagon hauling Jews to be murdered, and picked up by a farmer. The baby was baptized into Christianity through the advice of the local priest, and the farmer raised her as a daughter. In total, approximately 1,250 Jews were murdered during the occupation period.

After the War

The Red Army captured Ludza on the last week of July 1944. That year, a Soviet committee investigated the war crimes committed in Ludza, including the murder of the Jews. In the wake of its determinations, local Latvian war criminals were brought to trial. At the end of the war, Jews who escaped to the interior of Russia at the eve of the war returned to Ludza. The first returnees brought the victims of the Nazis in Ludza and the nearby villages of Rundēni (see entry), Pilda (see entry), and others to a Jewish burial in the local cemetery, which had not been damaged during the war. They also put up a monument over the graves of Rabbi Don–Yachya and several other Jews. The burial was conducted with the permission of the authorities – the Ministry of Religion in Riga and the city council – and with the assistance of technical equipment and special clothing that was given to the Jews. A Jewish community of about 100 individuals existed at the beginning of the 190s. The community maintained a cemetery as well as a synagogue. There was a rabbi who also served as a shochet [ritual slaughterer]. After his death, a Jew named Netanel Shmukler was invited there to fill his place as a shochet. The Jews of Ludza made aliya to Israel during the 1970s.

Sources:

Al'a 28, kuf, II.

Yad Vashem Archives, Yona Rodinov (collator): 0–33/672–681, 1040, 1043, 1048

Mordechai Neustat: Svitlychne, Udy, Al'a, 28 kuf, II.

David Elkind, Yh'z (memorial day) 12/164; Shlomo Kmeiski, Yh'z 12/232; Gasia Kmeiski Yh'z 12/184.

B. Eliav: Latvian Jewry

Mendel Bubeh, Jews in Latvia

The History of Bund, I, II

Shabtai Don–Yachya, “The Final Rabbi of Lutzin”, Or Hamizrach, Volume 15, Booklet 20, Tevet–Adar 5621 (1961).

Sh Daniel, the Family of Don Yachya, Jerusalem 1930.

Yisrael Zeligman: Family Tree

The Jewish Economy, 4, 5 (1937).

Dov Levin, With the Back to the Wall.

Shmuel Neiger, Leksikon of the New Yiddish Literature

Pinkas of the Riga Jewish Society and Philanthropic Activists

Yaakov Rosen, We Want to Live.

Z. Kamieika, “The Murder of the Jews of Lutzin”, (Jewish Courier, January 25, 1946, Chicago).

E. Avotins, Kas ir Daugavas vanagi.

Bruno Kalnins Latvijas S. Demokratijas – 50 gadi.

Max Kaufmann, Die Vernichtung der Juden Lettlands.

V. Salnais, Pilsetu apraksti.

Блюм И.А Кооперация среди евреев

Еврейская нциклопедия т.7 стр.635

Еврейское статистическое общество Еврейское население России

[Page 167]

Нагле Л. Отблески в озерах Лудзи Рига 1977.

Сборник материалов об кономическом положении евреевв России.

Справочная книга по вопросам образования евреев.

Еврейская старина 7 1912.

“Davar” (October 12, 1944)

“Di Zukunft” (January 1946)

“Der Amerikaner” (May 14, 1943).

“Haaretz” (October 28, 1944)

“Hamelitz” (April 22, 1885)

Translator's Footnotes:

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 10 Apr 2021 by LA