|

|

|

[Pages 1-50]

by Dov Levin

Translated by Shay Meyer

Edited by Toby Bird

[Translator's note: This article was written before the break-up of the Soviet Union. It does not reflect the recent history of Latvia. Latvia gained full independence from the Soviet Union in August 21, 1991]

|

A. General Background

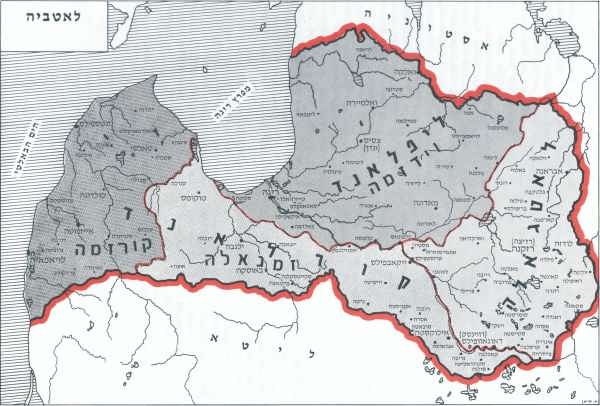

Latvia, currently known as “The Latvian Soviet Socialist Republic,” is the largest of and central to the three Baltic countries included in the Soviet Union. It occupies an area of 73,000 square kilometers on the eastern coastal plain of the Baltic Sea. It borders in the north with Estonia, in the south with Lithuania and in the east with Belarus [White Russia].

Historically, politically and culturally, this area is divided into three main regions:

With the development and enlargement of the city of Riga, and other cities that were established in the course of time, another independent force emerged the “Burghers.” These were the permanent citizens of the cities, who were eligible to vote or be elected to the city councils. Due to increasing military pressure of the Muscovite princes on the eastern areas of Latvia, especially on Latgale, the knights were obliged to request the help of the neighboring Polish state. As a result of this, the reign of the knightly order in Livonia came to an end in 1561, and most of their lands were turned over to Poland: The Courland region - with the exception of the Piltene district was declared a dukedom under Polish protection. Poland undertook to maintain the rights of the Germans as the ruling class and of the Lutheran church.

The Polish rule in Liflandia lasted for about 60 years until the Swedes conquered it in 1629. Following the “Northern War” and the defeat of the Swedes at the battle of Poltave (1709) against the Russian Czar Peter the first, the region fell under Russian rule in 1721 and became a region (gubernia) of Lifland. Riga had already surrendered to the Russians in 1710.

For a few years only, the Courland dukedom took part in the wars of its large neighbors, mainly those of Sweden, Poland and Denmark. The dukedom persisted under the protection of Poland, especially during the reign of the duke Yaakov, exhibiting economic and industrial growth. He invested in the development of trade and established a merchant and even a military fleet.

The city of Mitau (Yelgava in Latvian) served as the capital of the dukedom. The social order and status was maintained within the framework of the dukedom. The Germans maintained the servitude of local serfs. The local parliament, the Landtag, located in the city of Windau (Ventspils in Latvian), represented the interests of the city-nobles and of the land owners. Its decisions were subject to the approval of the duke.

In the second half of the 18th century, Courland fell more and more under the influence of Russia. Following an agreement in 1783 between the dukedom and Russia, a strip of the Baltic coast was handed over to the latter. The strip included Schlok, Dobeln and Majornhof. The whole of Courland was annexed to Russia in 1795, when Poland was divided for the third time.

The Pilten region (Piltene in Latvian) of Courland, was in point of fact a political and administrative enclave under the dukedom for most of the time. It included the Grobin district (Grobina in Latvian), the Hazenpoth district (Aizpute in Latvian) and part of the Windau district. In 1559 the region was given to king Friedrich of Denmark who placed it at the disposal of his brother the duke of Egnos. At the death of the latter, the region was handed to the direct rule of the king of Poland, and as a result, many of the local laws were set by the Polish “Saeima” [parliament]. When Poland was divided for the third time in 1795, this region came under Russian rule, just like the rest of Courland.

In spite of repeated Russian attempts to capture the Latgalian lands, this area was annexed to the Polish kingdom in 1582 as a special administrative unit with the name of Inflantkie Ksientwo, or Inflantia for short. A “voyevoda” (governor), who was appointed by the king of Poland, stood as head of the region. A sort of local parliament was set up, in which only the nobles took part. These suppressed the Latgalian peasants, imposed Catholicism upon them and left them illiterate. The Polish rule over Latgalia lasted for ten generations until the first division of Poland in 1772. The Latvian peasants in this region were freed from their bondage only in 1881.

By the end of the 18th century, the entire domain of Latvia was an integral part of czarist Russia, and merged into the administrative structure of this empire. It was divided up as follows: The Lifland sector (Vidzeme in Latvian) included the regions of Riga, Walk (Valka in Latvian), Wolmar (Valmiera in Latvian) and Wenden (Cesis in Latvian). The Courland sector included the regions of Windau, Pilten, Libau (Liepaja in Latvian). The Latgale sector included three regions; Ludzen (Ludza in Latvian), Rezitse (Rezekne in Latvian) and Dvinsk (Daugavpils in Latvian). The Latgale sector was merged into the Polotsk sector, and after 1802 into the Vitebsk sector. The czarist administration applied a policy of making these sectors more Russian. This policy was carried out systematically by government officials, headed by a minister for the sector. However, the German influence continued to a considerable degree in the town councils, country districts and local administrations: some Germans were “burghers”, some land-owners, barons and bearers of other noble titles.

The continued influence of the small but active and assertive German minority, as well as the connection to the west, had a profound influence on the western parts of Latvia. They gave a distinctly western nature to its towns, its villages and its economy, both in the manner of public organization and the way of life. This nature was entirely different from that of the rest of Russia. Both the legal procedures and the schooling continued to be German.

The integration of Latvia into the Russian empire considerably enlarged her economic development. Her convenient geographic location, her ports on the Baltic and her industrial infrastructure, which had existed for some time, were factors that contributed to this. As a result, a proletariat also flourished. The proletariat was aware of social-class levels and integrated with the political and revolutionary movement across Russia. In parallel, there arose a nationalist movement with the name “Young Latvians” among the local population. These nurtured cultural and political aspirations. Thanks to the improvement in living conditions, the population grew rapidly. On the eve of World War I the population of Latvia numbered about 2.5 million people. At this time this small country had 782 factories with 93,000 workers.

World War I brought great destruction to the regions of Latvia. Most of the basic industry was moved to the interior of Russia. The rest was obliterated. Commerce was paralyzed and about half of the agricultural holdings were destroyed. The general population dropped to 1.6 million people.

Courland was gradually conquered by the Germans when the war began (1915), and after the Russian revolution in 1917 they also conquered Riga. Immediately after Germany surrendered in November 1918, the temporary national council of Latvian public personalities led by Karlis Ulmanis declared the independence of Latvia and declared themselves as its temporary government. In December of that year the Red Army began to invade Latvia and by January of 1919 they took control of Riga, and with help from local supporters led by Peter Stuč ka they set up a communist government. Ulmanis and his government fled and took refuge in the port city of Libau (Liepaja), which held out under cover of the British navy. A compact German army, which included the “Landeswehr” established by the local nobility, under the command of von der Goltz captured Riga from the Red Army, but was defeated in a short space of time by a combined Latvian-Estonian army, and Ulmanis returned to Riga. After a series of battles waged by the Latvians with British and French assistance, most of the invading forces were driven out of the land and in 1920 a peace treaty was signed between independent Latvia on the one hand and the Soviet Union and Germany on the other hand.

In 1897 the Jews numbered 142,315 persons 7.4% of the total population. Up until the First World War the life, the destiny and the national and cultural character of the Jews in the three main regions of Latvia evolved and developed parallel to the events and the developments specific to each region. For this reason, the history of the Jews in each region will be reviewed separately, up to 1920.

B. The History of the Jews in the Liflandian Sector

There is reason to believe that a few Jews from Lithuania or Poland reached Lifland or Livonia during the reign of the Christian orders. These orders were generally hostile to the Jews. We can deduce the presence of Jews in this region during the 16th century from the agreement that was signed in 1591 by the king of Poland and the leader of the Teutonic order, as well as from other sources. According to the agreement, “Jews in Livonia are forbidden to deal in trade and to handle taxes and duties.” Jews continued to move into the region for the duration of the Polish rule. Some of them worked in handicrafts, peddling in villages, leasing of taverns and similar occupations. These activities built up a relationship between them and farm holders and local nobles. Nevertheless, their earnings were meager. In the course of time, there was a considerable increase in the number of Jewish traders who took part in the marketing of the agricultural produce from Lithuania. In return for grain, flax, wood, honey and similar produce, they exported tobacco, coffee, salt, iron and other products from this region products that were in demand in Lithuania. Jewish merchants also initiated the export of agricultural produce overseas, and thus played a substantial role in developing the export trade of both Poland and of Russia through the port of Riga.

The success of the Jews in these enterprises increased the anxiety of the local city dwellers, especially of the German traders, about the commercial competition. This background explains the frequent and repeated complaints and demands to the government that Jews should once again be forbidden to trade, that they be forbidden to settle and that their movement into the region should be restricted. This applied especially to the city of Riga whose “burghers” from 1592 and onwards consistently strove to stop the Jewish trading activity, and even demanded that the Jews be expelled. From time to time, even the nobles agreed to keep the Jewish traders out of their territory, but within a short time the earlier situation was restored, and the Jews continued to fill the role of bridging between the city and the villages in the feudal economy. Apparently for this reason, the number of Jews who lived in the country districts was larger than the number who lived in Riga during the 16th and 17th centuries. A proof of this is the large number of cemeteries from the period of the Polish rule which were found in the villages and in the farm holdings. During this period the total number of Jews in the region increased. This happened, in spite of the fact that there was no improvement in their legal status.

During the period of Swedish rule in Lifland (1629 - 1721), there was no lifting of restrictions on Jews who wanted to enter the region. But thanks to their energy, their connections with Poland and with Lithuania and their success in bringing further development to trade, their number increased even more, and their commercial activities became wider. The Swedish government encouraged the Jews to enter the Christian religion. When a few Jews were found (generally “social cases”) who agreed to change their religion, they were privileged by the attendance of high officials and nobles at their baptismal ceremonies.

The legal status of the Jews hardly changed when Lifland was transferred to Russian rule in 1721. In the initial years of their rule, the Russian rulers hardly took an interest in the question of the Jews. This changed following a decree published by the empress Yekatarina I in 1727, which ordered the expulsion of Jews from the cities of Russia. In Riga, the expulsion was carried out in 1743, in spite of a long chain of attempts and representations by the local administrators, especially by the minister of the sector, to soften the decree on account of the economic damage that would accrue to the region in general and to the city of Riga in particular.

A number of Jews returned to Lifland in the framework of the campaign of the Czarist regime to resettle the Jews in the southern part of the state, in “New Russia” (Kherson, Crimea and other places). An additional opportunity for the legal presence of Jews in Lifland came about through the transfer of the Schlok zone and other towns to Russian rule. An order with the purpose of developing the area was published in 1785 in the name of Yekatarina II, according to which Russians and foreigners were permitted to settle in the area without regard to their “race or religion”. According to this criterion, Jewish merchants from Courland and other places were permitted to settle. Their number reached 430 by 1811. Officially, they were given the title “Schlok citizens” or “Schlok merchants”. Even though the orders of 1788 allowed them to remain in Riga for a limited time (only 3 to 8 days), they were able to renew their permits and to remain in the city for much longer than allowed by the orders, and in fact they transferred their businesses to Riga. But it was only in 1822 that the “Schlok citizens and merchants” were actually allowed to stay in Riga with their children. On market days they were allowed to trade in the other cities and villages of the Lifland sector. By 1834 the number of Jews in this sector reached 532.

The question of limiting the number of Jews in the Lifland sector came up again in the discussions of the central government in Peterburg. In these discussions and their resulting decisions, the general tendency was for leniency: permission was given for the prevailing status (that is to say, a legal status was given for the residence of Jews who did not possess an appropriate permit) and regulations were eased for additional Jewish immigrants. As a result of this the number of Jews in the Lifland sector increased significantly: from 1221 in 1863 to 25,196 in 1881.

The lifting of the regulations concerning the merchants was undoubtedly a result of the wave of prosperity that swept the region in general, and the importance of the port of Riga for the foreign trade of the Russian empire in particular.

Indeed, it was not without reason that the Jews who had lived in Lifland for a long time preferred to live in Riga. The Jews from nearby areas (persons originating in “the pale of settlement” mainly from the nearby sectors such as Kovna and Vitebsk) were also drawn to this city. As a result, the majority of the Jews of Lifland were concentrated in Riga. This trend, which began in the 17th century, continued to increase and reached its peak at end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century. According to the census of 1897, there were 26,793 Jews in Lifland, (3.5% of the local population) and 22,097 of them lived in Riga (80%). Only 4,606 (20%) lived in the country towns and the villages. The majority of the latter lived in the following seven communities: Wolmar (Valmiera in Latvian), Walk (Valka in Latvian), Marienburg (Alūksne in Latvian) and Lemsa (Limbăzi in Latvian). At the time of World War I these communities numbered between 50 and 100 families. At that time, about 50,000 Jews lived in the whole sector (4.5% of the overall population). In the 1880's, the home-language spoken by the Jews of the Lifland sector were as follows: Yiddish 77%, German 22% and Russian only 1%. Nevertheless, the number of Jews in Lifland who were able to speak Russian rose from year to year. This number reached its peak at the time of World War I.

Since the Lifland sector (including Riga) was conquered by the Germans in the early stages of World War I, the Jews of this sector did not suffer much in comparison with other regions, and they were saved from the decree of expulsion which befell the surrounding sectors, for example Courland and Kovna. A census undertaken by the Joint towards the end of the war found that only 10 houses belonging to Jews were destroyed in all of Lifland in the course of the war. Nevertheless, the events at the end of the war together with the migration to the Riga metropolis, lead to further thinning of the country communities in Lifland. According to a census taken in Latvia after the war (1920), there were 29,110 Jews in the Lifland sector: only 4,389 of them lived in the country towns and villages, while there were 24,721 living in Riga, namely 80% of the Jews of the sector.

In view of this statistic, we can safely say that the history of the Jews of Riga was almost identical to that of all the Jews of Lifland up until World War I and also for a short time afterwards. The downward trend in the population of the country areas of Lifland became more pronounced in the interval between the two world wars. The Jewish population in these areas reached 1,908 in 1925.

C. History of the Jews of Courland (Kurzeme and Zemgale)

1. From the initial settlement of Jews until the end of the era of the dukes.

Just as in Lifland, Jews were forbidden to live in the Courland region ever since the time of the rule of the Teutonic knights. In spite of this, the first Jewish traders from Prussia arrived here by way of the sea, apparently in the 14th or 15th century. Some settled in the city of Hazenpoth (Aizpute in Latvian) as well as in other places in the Pilten region (Piltene in Latvian). Thanks to the special political status of this region, which was an autonomous enclave within Courland, the condition of the Jews was relatively benign in regard to receipt of permission to reside in the place, to practice commerce and trades and to keep up communities. At the end of the 15th century many of the Jews of the area owned estate assets. Later on, Jews came into other parts of Courland, mainly the southern parts. Most of them came from Lithuania, principally from the Samogitia region. After them, Jews also came from regions of Poland, especially in the aftermath of the pogroms led by Chmelnitzky. The main occupations of the Jews at this time were: peddlers, tavern operators, liquor makers, realtors.

The opposition to them increased at the end of the 17th century, opposition on the part of the citizens living in the cities. In the dukedom of Courland, just as in Lifland, the merchants and the artisans in particular saw the Jews and other “foreigners” as serious competition in the fields of commerce and economics, and pressed continually that they not be granted residence permits in the dukedom, and even more so that they not be allowed to participate in commerce. But the local nobility in the region generally had an interest in the presence of the Jews because of the benefit they brought in the marketing of agricultural produce and the importing of goods from other regions. In addition, the Jews were a source of considerable income on account of the levies and fines imposed on them from time to time for permits to reside in the area.

The opposing and differing interests of the ruling classes concerning the Jews were given expression in the “Landtag”, that is the governing body of the dukedom. Its decisions were subject to the approval of the duke. The approach of the dukes to the subject of the Jews was dictated largely by the benefits they could gain by exploiting the Jews. In point of fact, the Jews continued to be active in commerce, but they were forever under pressure and fear of new limitations and other decrees. Mostly, the decrees and limitations were renewed whenever there was a change in the reigning personnel.

In 1719 the “Landtag” passed a decision to give the Jews the right of residence in return for a payment of 400 Talers. This payment, which was called “Protection money” (Schutzgeld in German), was debated in many sessions of the “Landtag”. Nevertheless, in the course of several following decades, the subject of the Jews was debated repeatedly in this institution, and motions to expel them from the land were brought up, but these were never passed. In many cases, there was no serious intention to expel the Jews, but rather to extort as much money as possible from them, whether individually or collectively through the communities or through special evaluators. In the face of the never ending decrees and prohibitions, part of the Jewish population was forced to leave Courland, even if only temporarily. But the great majority remained in place.

The question of the rights of Jews became a subject for discussion among the general public, and not solely in the “Landtag”, and was discussed from many points of view in a series of papers that appeared in 1787. The first of these bore the title: “In favor of tolerance towards Jews in the dukedom of Courland and Zemgalen.” Nevertheless during those years, the “Landtag” refused to ratify the relief and rights granted by the duke to the Jews, and postponed the decision from session to session until the dukedom came to an end in 1795. In practice, the Jews enjoyed a positive status quo during the last years of the dukedom.

2. During the era of the rule of the Russian Czars.

When the dukedom of Courland and the Piltene zone were annexed to Russia, some ten thousand Jews lived there, less than half of them (4,581) were males. Only about 20% of the Jewish population lived in the cities of Mitau (Jelgava in Latvian), Hazenpot (Aizpute in Latvian), Goldingen (Kuldiga in Latvian) and Jakobstadt (Jekabpils in Latvian). Apart from a few hundred who lived in Mitau or in the Piltene district, and who were entitled to join the ranks of the merchants, the remaining Jews who lived in the towns occupied themselves with small businesses: buying and selling of used clothes or brokers, even though these occupations were forbidden to them. The lot of the remaining Jews of Courland, who continued to live on the estates or in the villages, was even more dismal. Some of these occupied themselves with the production of liquor, some operated taverns, some worked in handicrafts and some were wandering peddlers who moved from village to village.

When Courland became an integral part of imperial Russia, the Jews requested, through the minister of the sector, that a decision be taken regarding their legal status because most of them had been living in the region for 200 years without clear legal permission. This request resulted in no definite response, though the Jewish question came up from time to time in connection with the payment of a ransom by the Jews in return for not serving in the army. In his memoirs sent to the senate about this subject, the minister of the sector rejected the idea that a ransom be collected from the Jews, on the grounds that most of them were newly immigrated, had no connection with the place, and that they lived in abject poverty: “no bread to eat and no clothes to wear.” In the light of this situation, he recommended that the prohibitions which existed in the era of the dukedom should be enforced and that the Jews should be expelled from the sector.

In contrast to this, proposals with liberal and humane objectives were made to the senate. The advocate of these was Karl Heinrich Heikings, who was born in Courland. He was well informed about the local problems and had considerable influence in government circles especially with the court of the czar in Petersburg. There is no doubt that his proposals played an important part in the development of the new law concerning the Jews that was passed by the senate and also received the approval of the czar. By the authority of this law, the Jews of Courland at last became subjects with concrete rights of citizenship. The law was published on 12 May 1799, after a struggle that went on for about 200 years. Among other things, they now had the right to live anywhere in the sector and to engage in commerce and trades without fear of interference. In spite of this there was no let up in pressure from the non-Jewish merchants who demanded a limit to the entry of more Jews into the sector. (In 1802 there were 832 non-Jewish merchants and 101 Jewish merchants). In response to this pressure, the local authorities decreed that “only Jews and their descendants - who were registered in the sector at the time the law was passed in 1799 were entitled to reside there.” This decree was ratified by the senate.

A new law was passed in 1835 in response to a subsequent demand to reduce the number of Jews in the entire sector, a demand presented to the emperor by the merchants and artisans of Mitau. According to this law, all Jews who were registered in the most recent census were considered local citizens. The rest were to be expelled to the Pale of Settlement. Immigration of Jews to Courland from other sectors was forbidden. This law remained in force until the end of the Russian rule in Courland.

| Year | Number of Jews |

| 1797 | 10,000 (4,581 were men of whom 896 lived in the cities) |

| 1834 | 23,486 |

| 1850 | 22,743 (11,081 men and 11,662 women) |

| 1860 | 27,989 |

| 1875 | 34,180 |

| 1897 | 51,169 |

| 1913 | 60,000 |

| 1915 | 9,891 |

| 1920 | 20,223 |

An unconventional method of reducing the number of Jews in Courland is visible in the encouragement given them to emigrate to the south of Russia, mainly to the sector of Kherson. This did not require expulsion, and was consistent with the policy of colonization that the Russian government adopted at that time for economic and political reasons. In the framework of this emigration, 2,530 persons left 10 cities of the Courland sector in 1840. These people were from 341 families, representing 11% of the total Jewish population in the sector. Many of the Jews who stayed behind died in a cholera epidemic that broke out in Courland in 1848.

Even though the population of Jews in Courland was reduced in terms of numbers (see Table 1), the threat of expulsion still dangled over the heads of those who arrived after the cut-off date. The flow of Jews into the region continued even after this date, due to the prosperous economic development in the sector, due to its proximity to the Pale of Settlement and especially due to the possibility to merge into the businesses of the local Jews which continued to branch out in the 19th century. At this point in time, the overall population of Courland amounted to about 520,000 persons. The composition of the population was as follows: Protestants 436,000 (83.5%), Catholics 45,800 (9%), Pravoslavs 15,500 (3%) and Jews 22,743 (1.5%). The number of synagogues reached 29.

In 1904 the central government of Russian wanted to merge the Courland sector into the Pale of Settlement, by this was not implemented because of the opposition of the local German elements. At that time about 2/3 of the Jewish population of Courland lived in the cities and towns, and the German city dwellers had substantial fears of competition from the Jews. Against this background the police took action from time to time, where they expelled Jews who had recently arrived in Courland, or who were legally registered as artisans but were found to be active in commerce. This practice continued even after the memorandum of the minister Stolipin in 1907, in which he ordered the local authorities to refrain from expelling “illegal” Jews, but to be satisfied by not issuing residence permits. In fact, the threat of expulsion of these Jews from Courland remained until the end of the czarist regime.

3. Mass deportation in 1915.

An extensive and very brutal deportation of the Jews from a substantial part of Courland was carried out at the beginning of World War I following the orders of the military government of Russia. Deliberately false and imaginary accusations against the Jews were used to justify this. The accusations included treachery and helping the German army. The deportation was carried out on the 4th and 5th of May following notice of only 48 hours (the festival of Shavuot fell in this time). It affected all the Jews, the newly arrived as well as the long established, with the exception of those living in the villages to the east of Bauska. Additionally, about 10,000 Jews were saved from the deportation. They lived in Libau (Liepaja in Latvian), Hazenpoth (Aizpute in Latvian) and Grobin (Grobina in Latvian), which were under German occupation at the time. The Jews were removed to the interior of Russia to sectors such as Poltava, Yekatrinoslav (Dnipropetrovsk), Vladimir and Voronezh. Some of the deported persons were forced to cover great distances on foot, carrying on their backs the few possessions they owned, and also carrying their children of a tender age. Some of them died in the carriages while being transported, some became ill with serious diseases and some suffered nervous breakdowns. In general the deported were allowed to take only clothes and food with them. Their furniture, their tools and money owed to them by non-Jews all were left abandoned. This was also the case for the property, the furniture and the fittings of the institutions belonging to the Jewish community. Within a short time, all was pillaged by the local community. In fact this was the most severe damage inflicted on the Jews of Courland, who up to that time had not suffered any pogrom, in contrast with the other sectors of Russia.

After the deportation was almost complete, an order was given to cancel it, this on condition that the Jews agree that some of them would become hostages. The hostages would be hanged if Jews were found to be traitors. This subject raised a fierce debate among the Jewish public, but the matter of the deportation became irrelevant because most of Courland was conquered by the Germans. Nevertheless, the deportation continued in some villages east of Bauska which the Germans had not yet conquered. Approximately 40,000 Jews were deported from Courland. Only a few remained behind, and these suffered at the hands of the Russian army.

The deported Jews were carried by trains through Riga and other cities, where resident Jews provided material help and spiritual support. Food and essential equipment were brought to the carriages. The members of “Jekopo,” that is the committee to assist Jews who suffered as a result of the war, organized systematic help for the deported. Jekopo was established in Petrograd, formerly Petersburg, in 1915. Not all the Jews who were deported to the sectors in the interior of Russia remained there. In the course of time they were allowed to live in all the cities of Russia outside the Pale of Settlement with the exception of the two capitals, Petrograd and Moscow. Many of the deported died on account of the hardships of travelling, conditions of starvation and destitution in the places where they stayed in the interior of Russia and, in addition, on account of pogroms that took place in Russia during the war and the revolution. After the war, the survivors were permitted to return to their former homes in Courland, according to the terms of the peace treaty signed by Soviet Russia and Latvia in 1920.

According to a census made by the Joint towards the end of the war, 1,123 houses belonging to Jews and 92 community buildings were destroyed or damaged in Courland as a result of military activities.

4. Life within the Jewish community under Russian rule.

As we see from Table 1 above, the Jewish population increased six fold up until World War I during the Russian rule. At the same time, a distinct trend was evident for the Jews of Courland to concentrate in the cities: from 20% city dwellers in 1797 to 67% in 1897. These significant changes in the course of 100 120 years were largely a result of the prosperity of the area during that time. These trends had a considerable and positive influence on the life of the Jews. Among other things, it expressed itself in their increased entry into wholesale commerce, foreign trade (mainly export business), industry, investment in property and business and in free trades. As a result, the Jewish population enjoyed a period of material wealth, a rise in standard of living and culture and also public and political activity.

The fact that part of the Jewish population had been living for a long time in the villages and on the estates, and had occupied itself with peddling and operating taverns in gentile environments had a considerable influence on the Jewish way of life. During this period a generation of “country types” sprang up, a generation that lost contact with Jewish values and culture. In contrast, the concentration of Jews in the cities and the progress in the granting of civil and legal rights brought about an improved community life and in parallel the spread of higher education among them.

According to the description of the lives of the Jews in the 1850's and 1860's, as given by the historian Reuben Wunderbar, even the poorest of them tried to give their children at least a basic education; among the adults only very few did not master the German language. Many families continued to converse in jargon, meaning Yiddish, “but this phenomenon was disappearing.” According to Wunderbar, the Jews of Courland and Lifland achieved a high degree of civil rights in comparison with other places.

By the end of the 19th century there were 7 government schools in Courland, 22 private schools and 142 “Cheder” and “Talmud Torah” establishments. In the census of 1897, 30% of the Jews declared that German was the language spoken at home, but together with this, there was an increase in the number who spoke Russian, and a striking number of graduates of Russian universities could be found among them. The number of graduates of Dorpat (Tartu) university, in neighboring Estonia, was particularly large. One of these was the physician, public activist and important historian of the Latvian Jews, Yizhak Yaffe, who was well known for, among other things, the original documents about the Jews of Riga and Courland that he published in his book “Regesten und Urkunden der Geschichte der Juden in Riga und Kurland, Riga 1910”. The book was published by the Riga branch of “The Society of Promoters of Enlightenment”.

At the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century a more positive attitude to the values of Jewish culture arose among the Jews. This resulted from the influence of the two central movements: Zionism and the “Bund.” “Improved Cheders,” whose language of instruction was Hebrew, were opened in the cities and towns of Courland. In the course of time Hebrew gained respect alongside Yiddish in the Jewish institutions of learning. Many of the Jews in Courland, who originated in Torah-oriented Lithuania, continued to maintain family and cultural ties with the country of their origin, and even kept up the way of life and the customs that were based on the Jewish traditions that were common in Lithuania. They were called “Kurlandische Litvaks” for this reason. There was no Yeshiva in Courland (with one exception in Piltene, and even that existed for a short time only) so the religious Jewish home-owners sent their sons to study Torah in well known Yeshivot in Lithuania, and brought husbands for their daughters from there. In spite of this, Courland nurtured a line of Rabbis in the course of time. They were well versed in the Torah, and their fame spread far and wide. Among these were Rabbi Mordechai Y. Eliashberg and Rabbi Yizhak Cook the Cohen, who held the holy office in Bauska and Rabbi Levi Avchinsky from the Vilna sector who was chosen for the rabbinical office in the city of Auce, and later served as “Official Rabbi” in Jelgava the city of his birth. He was also a historian and wrote the book “The History of the Jews of Courland” in 1908. The Rabbis from the Rabiner, Samonov, Livtenstein and Nurok families even formed “dynasties” of Rabbis who held office in succession in the communities of Bauska, Skaitskelna, Jelgava, Windau and Tukums. Several of them even achieved state recognition, receiving titles such as “Official Rabbi,” “Regional Chief Rabbi” etc. Together with this, some communities were dissolved by the state in Courland starting from 1844, and some of the associated responsibilities were transferred to the local city council (the magistrate). In order to handle these responsibilities, the Jewish public was required to elect a number of officers every three years. These officers undertook the task of collecting taxes from the Jewish residents.

At the time of the elections for the “Duma” (that is the parliament that existed in Russia at the time of World War I), many of the Jews of Courland lived in cities. Thus, according to the election laws, they were entitled to participate in the primary elections that chose candidates for the parties. On account of their electoral weight, and through agreements drawn up with the other national parties in the sector (the Germans, the Latvians), the Jews were able to send a representative of their own to each of the four “Dumas”. But since the relations between the Jews and the Germans were generally not good, these agreements were usually based on immediate common political interests. In fact, the agreements were technically “ad hoc” in nature.

A similar relationship existed between the Jews and the Latvians. At the time of the revolution in 1905, many of them walked shoulder to shoulder with the Jews in the realm of the political struggle. With the support of the Latvians, Nissan Katznelson from Libau was elected to the first “Duma” (where there were a total of 12 Jews). In 1907 Yaakov Shapira from Windau was elected to the second “Duma” (where there were 3 Jews). In 1908 Lazar Nisselowitz from Bauska was elected to the third “Duma” (in which there were 2 Jewish representatives). In the elections for the fourth “Duma” that took place in 1913, Dr. Yechezkiel Gurwitz from Jekabstadt was elected with support from the Germans. Together with him, there were three Jews from all of Russia in this “Duma” which was the last. At the time when the Jews were expelled from Courland, representative Gurwitz together with Rabbi Dr. Mordechai Nurok took the lead in the demonstrations and the activities to foil the expulsion.

Towards the end of World War I, young Jews from Courland fought in the ranks of the Baltic “Landswehr” led by sons of the local agrarian nobility against what was termed “The Russian Bolshevik barbarism.” These youth were mainly from long standing Jewish families in Courland, who were influenced by the German culture, spoke German and were anti-Russia in their views. There were also young Jews who volunteered for the Latvian units that fought in the war for Latvian independence.

D. The history of the Jews of Latgale

1. Prior to the onset of the Russian Administration (1772)

Due to its relative distance from the main centers of Poland and Lithuania, and also apparently due to its poor economic state and lack of development of the population, few Jews from central and eastern Europe were drawn to Latgale (or Inflantia as it was known at the time of the Polish administration). In any event, Jews arrived in this region at a much later time than in other parts of Poland. According to all the signs, a mass settlement of Jews in Latgale began in the first half of the 17th century, in the wake of the pogroms and the destruction suffered by many communities in the south. As with other Jews in the adjoining territories, those coming to Latgale found occupations as tavern operators, as customs brokers at border stations, as liquor brewers and distillers, as property agents, as small shop-keepers and as peddlers in the villages. In the course of time, some of them became tenants on estates, and began to trade in grain and wood with overseas countries. Most of them resided in villages and on estates due to the nature of their occupations. At the end of the 17th century, and mostly in the 18th century, a larger fraction of them became artisans. At this time, there was already a concentration of Jews in the central cities of the region, such as Dvinsk (Daugavpils), Kreitsburg (Krustpils) and Karsava. According to a census that was taken in 1766 for the purposes of collecting taxes, there were 2996 Jews in the region (excluding infants).

2. During the Russian Administration up till 1920

At the time the region (the Polochek sector) was transferred to Russia, 4,000 to 5,000 Jews were living there. In the course of time, the sector was included in the Pale of Settlement with all its consequences for the Jews that lived there. The Jewish communities continued to exist and “were tolerated” by the regime, as had been the case during the Polish reign. In spite of this, in those places where Jewish communities did not exist, the regime had an interest to establish such communities, since this made the collection of taxes from the Jewish population easier and more efficient. A classification of the population of the cities of Belarus (to which belonged the Polochek sector including Latgale) was enacted in 1778. It divided the population into two classes: merchants owning property worth more than 500 rubles, and city dwellers. Even though the majority of Jews at that time lived in villages and on the estates, most of them were registered as belonging to the class of city dwellers. With the publication of the law that required members of the city dwelling class to actually live in the city, multitudes of Jews forfeited their status and livelihood in the villages. The owners of the estates were given strict instructions not to give shelter to the Jews. This brought an economic disaster on the Jewish population. But even the estate owners suffered economic losses from this state of affairs, through the absence of Jewish tenants, brewers, distillers and the like.

Jewish advocacy for the cancellation of the decrees therefore found sympathetic ears, and in 1786 they were allowed to return to their previous occupations, with the exception that they were not permitted to own property in the villages. The decree was renewed in 1808 when the region was incorporated into the Vitebsk sector.

From this point on until the end of the Russian regime, conditions in the cities and towns of Latgale were the same as in most other sectors of the Pale of Settlement: dense population, economic deprivation, harsh conditions of living and hygiene and so on. According to data from the YKA society in 1898, 18.5% of the Jewish families in this sector were in need of social support. This fraction only increased as time went on. The economic status of the Jews of Latgale became more and more like the status elsewhere in the Pale of Settlement.

At the end of the 19th century the Jews made up 71% of all the artisans in the region. Their occupations were distributed as follows: clothing 39.9%, shoes 16.2%, carpentry 10.8%, food 11.6%, metal 9.3%. The workshops were generally small, and typically 2 to 3 persons (including family members of the owner) worked in each. 3.3% worked in agriculture. A few large factories existed in Dvinsk, which was considered at that time to be an industrialized city. 32,400 Jews lived in this city in 1897. They comprised a little more than half of the Jews of the whole sector (see table 2 below). The number of Jews in need of social support was high in this sector, taking second place in the Pale of Settlement (after the city of Vilna).

As we see from the table below, the number of Jews was reduced by more than 60% after World War I. Some of them returned, apparently from Russia, where they had gone during the War. Others went to large cities in Latvia, especially to Riga.

| Year | Jewish Population |

| 1766 | 2,996 (excluding infants) |

| 1847 | 10,918 |

| 1897 | 64,239 |

| 1914 | 80,000 |

| 1920 | 30,311 |

Unlike the Jews of Courland and Lifland who differed in some respects from the Jews of Russia, the Jews of Latgale were an integral part of them. Like the Jewish communities in Lithuania and “Reisen” (White Russia), the Jewish communities of Latgale had deep-rooted Jewish folklore and traditions. The dominant language between Jews at home and in public was Yiddish. Every community maintained a “Cheder” of the type that was common in Eastern Europe at that time. In the course of time, many of them were upgraded. A lot of this was thanks to the Hassidic Chabad movement which spread to Latgale from the Chabad center in Lubavitch in the neighboring “Reisen.”

Some of the communities of Latgale became famous in the Jewish world for their spirituality and expertise in the Torah. One example of this was Luzin (Ludza in Latvian) with its rabbinical dynasty from the house of Don Yehia. Rabbi Meir Simha the Cohen and Rabbi Yosef Rosin, both of Dvinsk, were well known, the latter being called “der Ragatshaver.”

In addition to being connected with the Jews of the Pale of Settlement on the traditional and cultural planes, the Jews of Latgale were integrated in the national and revolutionary movements, which earned them supporters among the Russian Jews at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th centuries. Jews in Dvinsk, Rezhitsa (Resekne in Latvian) and other towns of the region joined up in droves with the Zionist camp, or with the “Bund” movement or with other political parties. Many of them took an active part in the events of the revolution of 1905, and also in the pioneering immigration to the land of Israel.

In the course of World War I some of the Jews of Latgale served in the Russian army. The extensive military activities in this region brought a great deal of suffering on the Jewish population.

According to a survey carried out by the Joint towards the end of the war, 1940 houses in Latgale belonging to Jews were damaged or destroyed in the course of the World War and also 101 public buildings mainly in Kreitsburg (Krustpils in Latvian), Liwenhof (Livani in Latvian), Viški and others.

Not a few of Latgale Jews fought alongside the Latvian army in the Latvian war of independence. Generally these were from the towns (some of them members of the same family) that were on the battlefront with the Bolsheviks. Following the partial withdrawal of the Bolshevik armies to the east, and with the general call to arms in the region, many Jews joined up with the partisan brigade of Latgale. According to a partial list that was drawn up in the 1930's it emerges that some came from the following towns: Balvi 26 men, Vilaka 25, Rugāji 7, Baltinava 5 and other places 6. The lively enrollment of the Jews of Latgale into the Latvian army was accompanied by widespread popular support and a warm relationship towards the fighting men on the part of the Jewish population.

The exceptional character of the Jews of the region, in terms of folklore and traditions, did not vanish even when the region was annexed to the Latvian state and the Jewish community was integrated with the other Jews of Latvia.

A. General Background

At the time when independent Latvia was established, there were only 1½ million inhabitants within its recognized territory as compared with 2½ million on the eve of the outbreak of World War I. Near the time of World War II Latvia had nearly two million inhabitants. This means that the number of inhabitants did not return to the number prior to World War I during the entire period of independence, in spite of the natural growth and the return of a quarter of a million refugees (mainly from Russia) who returned to their homeland by the end of the 1920's.

For almost the entire period of Latvian self-rule, 20% of the population was concentrated in Riga, the capital city. In spite of the fact that the importance of Riga in terms of international trade was considerably reduced, Riga continued to be an important port and trade center in north-east Europe. In terms of area and population, Riga was the only metropolis in all of Latvia. The other four large cities, namely Liepaja (Libau), Daugavpils (Dvinsk), Jelgava (Mitau) and Ventspils (Windau) had a combined population of only 150,000, amounting to 7.5% of the total population. Independent Latvia had another 8 cities whose population varied between 5,000 and 15,000 people, namely Rezekne (Reshitsa), Cesis (Wenden), Valmiera (Wolmar), Tukums (Tuckum), Kuldiga (Goldigen), Jekabpils (Jakobstadt) and Ludza (Ludzen). In 1935 these cities had a combined population of 70,474, comprising 3.5% of the total population. Apart from these, independent Latvia had another 19 towns with populations between 2,000 and 5,000 and 27 small towns with less than 2,000 people. In 1935 the total city-dwelling population of Latvia came to 710,563 citizens, making up about 36% of the total population.

The majority (64%) of the population lived in villages and engaged mainly in agriculture. Up until the agrarian reform, about half of the agricultural land belonged to the nobility. The distribution of the population between the cities and the country was not uniform in all regions. Latgale was the region in which the majority of the people were country folk, while Kurzeme (the south western geographic region of the former Courland) had the most city-dwellers apart from Riga. As before, the Latgale region was the most backward in terms of culture. In the 1920's the percentage of illiteracy in Latgale was 46% as opposed to 5% in Kurzeme.

Even after independence was achieved, following a series of wars, national struggles and extended periods of chaos, the country was largely destroyed, especially economically. As a result of the deliberate military activity in this country that took place during 6 years of warfare, a large part of the industry was destroyed. Many of the skilled workers and their managers, who were transferred to the interior of Russia in the course of World War I, did not return after the war. As a result of the new geo-political situation, the country was isolated from the huge Russian market.

Thanks to extensive aid from the countries of the west, an energetic reconstruction of industry was undertaken. The local currency (the Lat) was stabilized relatively quickly, and a striking revival of foreign trade took place, this in spite of the loss of the traditional markets of Latvia in the depths of Russia that was felt for many years. Even so, Latvia did not regain its position as gateway between east and west as was the case before World War I. Consequently, the mainstay of the Latvian economy between the two world wars rested on agricultural produce, especially on linen and dairy products, which formed the main components of its foreign trade. An agrarian reform was implemented in 1920 with the aim of encouraging the activity of the peasants, who made up the overwhelming part of the Latvian nation: 1,300 large estates were distributed among the peasants, estates that previously belonged mainly to the German nobility. Even after this, the German minority continued to be a national group that wielded influence far in excess of their numerical proportion.

Opposite the majority ethnic group (the Latvians) who comprised 75% of the population (according to the census of 1935), the ethnic minorities made up a significant fraction with their numbers reaching 25% of the Latvian population. The Russians held first place 12%, followed by the Jews 4.8%, with the Germans in 3rd place 3.2%, Poles 2.5% and others about 2%. In order to maintain the traditional cooperation between the Latvians and the remaining minorities, representatives of the Latvian political groups that participated in setting up the state agreed to integrate the minorities in the building and the management of the state and to guarantee their cultural and national rights. This policy was in line with the aim of the Latvian establishment to prove to the western nations, upon whose patronage they depended, that the new Latvia was a democratic and peace loving country that respected law and order and had a clear parliamentary regime. Consequently, as early as 1918, the national council included representatives of the minorities (4 Germans and 3 Jews) together with the 47 representatives of all the Latvian political parties. Towards the end of 1919 the national council enacted the special law concerning schools for the national minorities. According to clause 1 of this law “the schools of the national minorities are autonomous”. This meant that the minorities were entitled to establish and to manage educational and cultural institutions using their chosen language. The law also established the national mechanisms and responsibility for the upkeep of these institutions, and their relationship with the central regime. The minorities managed the schools themselves. The other cultural institutions were also managed by the minorities through central facilities that were established for each institution. In order to implement the law, a special department in the ministry of education was set up for each national minority group. A department existed for the Germans, for the Russians, for the Jews, for the Poles and for the Belarusians. According to clause 7 of the law, the manager of a department represents his ethnic group in all matters of culture, is empowered to establish connections with the other departments in the ministry of education, and is entitled to present advice on matters under his jurisdiction at all meetings of the chamber of ministers. City councils were required to allocate a budget for these institutions in proportion to the number of persons of the minority living in the city.

At the inaugurating assembly that met in 1920 with a quorum of 150 representatives, there were 17 representatives of minority groups: 6 Jews, 6 Germans, 4 Russians and 1 Pole. According to the constitution that was accepted by the inaugurating assembly, it was determined that Latvia would be a democratic republic with a “Saeima” (parliament) having 100 members.

In the four “Saeimas” that ruled independent Latvia in the years 1922 to 1934, the fraction of members representing minorities reached only 16% to 19%, even though the minorities made up 25% of the total population. The reason for this was largely due to the disunity within the minorities themselves. Even though the minorities had similar interests, and in spite of the fact that the rights guaranteed to the minorities were cut back from time to time, their representatives in the Saeima were unable to present a united front for any length of time, or even a systematic framework of a minority block. Generally they cooperated in an “ad hoc” manner on matters that concerned their national autonomy, for example: the use of their language in government institutions, instances of discriminatory deprivation, and similar cases. On several occasions, all or some of the minorities took part in causing the dissolution of the government. There was considerable political disunity even among the Latvian majority, largely due to social and economic differences. All of this resulted in an exaggerated number of political parties (in 1931 there were 24 parties in the Saeima), and in instability of the government and the economy. Among other things it brought about frequent changes of the government. The government changed 13 times in 17 years.

On the international front, there was continued pressure on independent Latvia from the Soviet Union towards tightening of mutual connections including even a military pact. But Latvia was against this largely on account of the bitter feelings in the majority of citizens remaining from the attempt to establish a Soviet government in the land in 1918/1919. For the same reason, the tiny communist party in this country did not enjoy much support. The government-establishment fostered a movement in the opposite direction in the form of a nationalist semi-military organization called the “Aizargs” meaning “homeland guard.” In due course right-wing elements set up a militant Latvian organization named “Perkonkrust,” meaning “Cross of Thunder” with a nationalist and fascist ideology. The Nazi accession to power in Germany also influenced the penetration of autocratic and racist ideas into Latvia through many members of the local German minority. Together with this, they demanded a tightening of connections with Germany, even to the extent of annexation.

In this state of economic instability and pressures from within and from without, an extreme right-wing revolution took place on 15 May 1934 led by the leader of the “Peasants party,” Carlis Ulmanis, who was prime minister at the time and had served in this capacity at earlier times also. Ulmanis (who was thenceforth called the leader) carried out the revolution with the help of the “Aizargs” organization. The revolution brought the democratic regime in Latvia to an end. The Saeima was dissolved, the political parties were disbanded and many of their leaders were jailed. Rights of the individual and the autonomy of the minorities were drastically reduced. For internal political reasons, the “Perkonkrust” organization was also disbanded, and its leader G. Celmins immigrated to Germany.

During the six years (1934 1940) of autocratic rule by Ulmanis, the diplomatic and military pressure on Latvia increased and expanded, on the one hand from the neighboring Soviet Union in the east and on the other hand from the nearby Nazi Germany in the west. The obstinate Latvian stance in a position of clear neutrality, and her attempts to overcome these pressures with the help of the western powers and by drawing up a treaty of friendship and mutual aid with the neighboring Baltic States Lithuania and Estonia (“The Baltic Agreement”), did not stand up at the critical time. According to the surprise agreement of friendship that was signed in 1939 between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union (the Molotov - Ribbentrop Pact), Latvia was assigned to the Soviet sphere of influence. This forced Latvia to sign a “Defense Pact” with the Soviet Union in October 1939 which provided the Soviets with military bases in the port cities of Liepaja, Ventspils and other places.

Following the German-Soviet agreement, 52,500 local German nationals were transferred from Latvia to Germany at the end of 1939. They comprised about 80% of the long-standing German population, who had been resident in Latvia for hundreds of years. (Some of them returned to Latvia a year and a half later, following the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, together with the officials of civilian government that came in its wake).

On the 17th June 1940, the Red Army took complete control of Latvia (and of the other Baltic countries), and immediately set up a pro-Soviet government. Carlis Ulmanis was arrested and was deported to Siberia in the course of time. At the time of the elections for the “Peoples Saeima,” only the “party of the workers bloc” took part, and of course earned 97.8% of the votes.

At its very first meeting, the Saeima decided in favor of annexation to the Soviet Union. The Supreme Soviet in Moscow ratified the annexation on 5 August 1940, and Latvia became a Soviet Socialist Republic and an integral part of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (More on this later).

B. Statistical and Demographic Data

As with the general population of Latvia, the Jewish population diminished as a result of the events of World War I. But the degree of diminishment was disproportionately larger: according to the first census of the population in independent Latvia that was undertaken on 6 June 1920, the number of Jews there was 79,644 as compared with approximately 190,000 in 1914, which is to say a reduction of 58% (at that time, the general population was reduced by 37.5%). In a number of towns in Latvia where there was an absolute majority of Jews before the war, it came to pass that after the war the non-Jews constituted a substantial majority of the citizens. Even after more than 10,000 deported or fugitive Jews returned from Russia in the early 1920's, the Jewish population of Latvia was not restored to even half of what it had been before the war. This is clear from the four sets of census data collected in independent Latvia between the World Wars (see Table 3).

| Location | Year 1920 | Year 1925 | Year 1930 | Year 1935 | |

| Riga (the city) | Number of Jews | 24,721 | 39,459 | 42,328 | 43,672 |

| % of Latvian Jews | 31.0 | 41.2 | 44.3 | 46.7 | |

| % of total population | 13.6 | 11.68 | 11.20 | 11.34 | |

| Vidzeme | Number of Jews | 4,389 | 1,908 | 3,072 | 2,458 |

| % of Latvian Jews | 5.5 | 2.0 | 3.3 | 2.6 | |

| % of total population | 10.6 | 0.47 | 0.76 | 0.61 | |

| Kurzeme | Number of Jews | 14,883 | 12,900 | 12,012 | |

| % of Latvian Jews | 14.6 | 13.7 | 12.9 | ||

| % of total population | 5.19 | 4.48 | 4.10 | ||

| Zemgale | Number of Jews | 20,223 | 7,665 | 7,384 | 7,363 |

| % of Latvian Jews | 25.4 | 8.0 | 8.7 | 7.9 | |

| % of total population | 4.0 | 2.78 | 2.56 | 2.46 | |

| Latgale | Number of Jews | 30,311 | 31,760 | 28,704 | 27,974 |

| % of Latvian Jews | 38.1 | 33.2 | 30.4 | 29.9 | |

| % of total population | 6.1 | 5.89 | 5.30 | 4.93 | |

| Total | Number of Jews | 79,644 | 95,675 | 94,388 | 93,479 |

| % of total population | 4.99 | 5.19 | 4.97 | 4.97 |

From the data in Table 3 we observe that the Jewish population in independent Latvia reached its peak in the year 1925, amounting to 95,657 persons (comprising 5.19% of the overall population). But this peak was only 50% of the number in 1914. As mentioned before, the number of Jews in 1914 was about 190,000. From 1925 and onwards, there is a decrease in absolute numbers and also as a fraction (of the total population), in the whole country, as well as in each of the regions with the exception of Vidzeme (Lifland) especially the city of Riga. The trend towards urbanization of the Jews of Vidzeme occurred largely towards the end of the 19th century, but partly even earlier. In the years immediately following World War I, many refugees returning from Russia to independent Latvia preferred to settle in Riga. Later, many young people from the country villages and small towns also streamed into this metropolis in search of a livelihood. As a result, this process had consequences for the other areas: in 1920 almost 38% of the Jews of Latvia were concentrated in Latgale, whereas in 1935 this fell to only 30%. Nevertheless, this region remained the most significant in terms of the number of resident Jews in the 1930's, with the obvious exception of Riga. The distribution of the Jewish population can be seen in Table 4.

| Region | Jewish communities |

Distribution of communities according to population | ||||

| Up to 500 people |

500 to 999 people |

1000 to 2499 people |

2500 to 4999 people |

5000 or more people |

||

| Courland (Kurzeme and Megale) | 21 | 10 | 7 | 3 | - | 1 |

| Lifland (Vidzeme) | 9 | 8 | - | - | - | 1 |

| Latgale | 22 | 9 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 52 | |||||

It appears that at the beginning of the 1920's a half of the Jewish communities were small in terms of number of people, and under these conditions it was most likely that they found it difficult maintain adequate community services and institutions. Communities with an intermediate number of people were to be found mainly in Latgale, together with a few in Courland. Vidzeme did not have any communities of intermediate size. We can conclude from this that in Vidzeme, community services and institutions existed only in Riga.

|

|

Riga continued to be a center of attraction for the Jews of Latvia, and at the outbreak of World War II more than half of the Jews of this land were concentrated in this metropolis. At this point we wish to point out that the tendency to urbanization was a characteristic that applied to all the Jews of Latvia. In the 1920's 72,039 Jews, amounting to 90.45% of the Jewish population in this land, lived in the cities and towns. By 1935, 86,555 Jews (92.59%) lived in the cities and towns of Latvia. and of these, about 80,000 (85%) lived in urban communities. See Table 5.

| City | 1920 | 1925 | 1930 | 1935 | ||||

| Number | % of total |

Number | % of total |

Number | % of total |

Number | % of total |

|

| Riga | 24,721 | 30.60 | 39,459 | 11.68 | 42,328 | 11.20 | 43,672 | 11.34 |

| Daugavpils | 11,838 | 40.8 | 12,657 | 31.40 | 11,636 | 26.92 | 11,060 | 24.95 |

| Liepaja | 9,758 | 19.0 | 9,851 | 16.21 | 7,908 | 13.81 | 7,379 | 12.92 |

| Rezekne | 4,148 | 41.5 | 3,911 | 30.99 | 3,577 | 28.21 | 3,342 | 25.43 |

| Ludza | 2,050 | 40.6 | 1,907 | 34.31 | 1,634 | 30.49 | 1,518 | 2.37 |

| Jelgava | 1,527 | 7.7 | 1,998 | 7.05 | 1,977 | 5.98 | 2,039 | 5.98 |

| Kraslava | 1,446 | 40.5 | 1,716 | 38.26 | 1,550 | 36.19 | 1,444 | 33.77 |

| Varaklāni | 1,304 | 73.0 | 1,356 | 76.63 | 995 | 51.27 | 952 | 57.32 |

| Krustpils | 1,204 | 62.9 | 1,331 | 37.75 | 1,149 | 35.76 | 1,043 | 28.52 |

| Preili | 995 | 53.6 | 1,005 | 52.07 | 982 | 51.06 | 847 | 50.97 |

| Karsava | 910 | 47.5 | 907 | 46.21 | 865 | 46.91 | 785 | 41.98 |

| Ventspils | 683 | 10.5 | 1,276 | 7.79 | 1,275 | 7.39 | 1,246 | 7.95 |

| Jekabpils | 676 | 19.0 | 806 | 14.25 | 796 | 14.20 | 793 | 13.61 |

| Livani | 637 | 33.3 | 1,032 | 33.45 | 1,010 | 31.38 | 981 | 17.81 |

| Bauska | 604 | 20.8 | 919 | 18.01 | 768 | 15.86 | 778 | 15.81 |

| Tukums | 597 | 13.4 | 1,025 | 14.30 | 968 | 12.64 | 953 | 11.71 |

From Table 5 we observe the reduction in the size of the Jewish population in each of these cities and towns in the course of one generation: the numbers for the town of Krustpils (Kreitsburg) demonstrate this trend in a most pronounced way. Krustpils had an absolute majority of Jews (2/3) in 1920, while their numbers in 1935 had fallen to less than 1/3. Furthermore, in contrast to 5 towns whose population consisted of 1/3 to 1/2 Jews in 1920 - Resekne (Reziche), Livani (Livenhof), Karsava (Korsovke) and Kraslava only two remained in 1935 (the last two). Of the 16 places of settlement shown above, only two towns retained a majority of Jews in 1935 - Varaklāni and Preili (both of these in Latgale).

The process of urbanization, with all its consequences, evidently had a substantial influence on a number of important demographic trends within the Jewish community of Latvia. Thus, for example, while the group of 20-year-olds accounted for 43.27% of the Jews in 1921, this group shrank to only 29.7% in 1935. The aging of the Jewish population in the course of 15 years was the result of the practice of having one or two children, which became more and more common among the Jewish families who moved into the large cities. Data on additional demographic trends are presented in Table 6.

From Table 6 it emerges that the proportion of marriages among the Jewish population was higher than the proportion among the population as a whole. At the same time, the rate of births among the Jews showed a downward trend (27%). In contrast one observes an increase in the rate of deaths (13%) among the Jews. As a result of these two trends, there was a drop in the rate of natural regeneration of the Jewish population to the extent of 80% (during the same period, the rate of natural regeneration among the non-Jews dropped by only 51%).

Though it was substantial, the drop in the rate of natural regeneration was not the prime cause of the reduction of the Jewish population. The extensive decrease in the number of Jews especially from 1925 and onwards had its main origin in the massive emigration of Jews from Latvia to other lands. About 4,500 persons migrated from Latvia to the land of Israel between the two world wars, while 2,500 migrated to the United States and to other overseas countries.

From the mid 1930's onwards there were at least several hundred Jewish refugees from Germany living in Latvia, and later on also from Poland. A small fraction of these managed to get out of Latvia before the Holocaust.

| Year | % Jews in overall population |

% married | % births of Jews |

% deaths of Jews |

% natural regeneration |

| 1925 | 5.19 | 5.33 | 4.25 | 3.51 | 5.75 |

| 1930 | 4.97 | 5.06 | 4.00 | 4.04 | 3.92 |

| 1935 | 4.79 | 6.12 | 3.75 | 4.10 | 2.32 |

C. Politics and Citizenship

The absolute equality of rights granted to the Jews, and to all the other citizens, of independent Latvia enabled them to integrate into the internal politics of the country as well as into other aspects of life. This was felt mainly at the end of the term of office of the national council. In 1920 there were 7 Jewish representatives in the council.

The inaugural convention with 150 members included 8 (5.3%) Jewish representatives: Mr. Mordechai Dubin(Agudat Yisrael), Rabbi Aharon Bar-Nurock (Mizrachi), Yaakov Helman (Zionist Youth - Union), Zenou Taron (General Zionist), Leopold Fishman and Yaakov Landau (Jewish Nationalist Party), Y. Beratz and Julius Rabinovitch (Bund). The last two were elected together with other representatives of the Latvian Social-Democratic Party. Respect for the Jewish voters resulted in the postponement of the elections for the first Saeima from the beginning of September 1922 to the end of that month to avoid conflict with the Jewish festivals.

The number of Jewish representatives in each of the four Saeimas that governed independent Latvia after the inaugural convention was initially 6 (6% of the representatives in the Saeima) falling in the course of time to 3 (3%), as can be seen in Table 7.

| Saeima | Party affiliation | |||||

| Total Jewish Representatives |

Agudat Yisrael |

Mizrahi | National Democrats |

Zionist Youth |

Bund | |

| First (1922-1925) | 9 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 5 | 2 | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | |

| Third (1928-1931) | 5 | 1 | 2 | - | 1 | 1 |

| Fourth (1931-1934) | 3 | 2 | 1 | - | - | - |

It is apparent that, with the exception of the fourth Saeima, the fraction of Jewish representatives (out of 100 representatives) in each of the other Saeima's corresponded approximately to the fraction of Jews in the overall population. Most of these representatives were elected by the votes of Jews only, while the competition between the various electoral lists took place entirely within the Jewish neighborhoods and was conducted in the languages spoken by the Jews. The vote of the Jewish electors was influenced by ideological and social issues as well as by the nature of their relationship to the personality at the head of each electoral list. This relationship correlated with the differing traditions of the various geographic regions, as can be seen in Table 8.

| Electoral List | Votes Cast in the Region | |||||

| Riga | Vidzeme | Kurzeme | Zemgale | Latgale | Total | |

| Agudat Yisrael | 6,048 | 469 | 1,058 | - | 5,890 | 13,465 |

| Mizrahi | 3,287 | 202 | 4,416 | 2,200 | 439 | 10,544 |

| Zionist Youth | 1,891 | - | 516 | 529 | 3,466 | 6,402 |

| Bund | 1,423 | - | - | - | 4,308 | 5,731 |

| National Democrats | 1,875 | - | 398 | 289 | 161 | 2,723 |

| Zionist Federation | 235 | - | 223 | - | 505 | 963 |

| Total Votes for Region | 14,759 | 671 | 6,611 | 3,018 | 14,769 | 39,828 |

One sees that the Jewish voters of the Latgale region supported mainly three electoral lists:

“Agudat Yisrael” which received many votes from the Hasidim who were concentrated in this region. “Agudat Yisrael” was led by Mordechai Dubin a member of the Chabad movement and an associate of the Rabbi of Lubavitch. The electoral list of the Zionist Socialists represented by the “Zionist Youth” party lead by Matityahu Landau, and the electoral list of the “Bund” party lead by Dr. Noah Maisel received the votes of common people and of proletarian elements that were active in this region since the revolution of 1905.

On account of this, the Bund achieved representation only in Latgale. In the Courland region (especially in Zemgale) most of the Jews voted for the local leaders favored by the rabbis the brothers Mordechai and Aharon Bar-Nurok. This trend was especially pronounced in the elections for the third Saeima in 1928: the Mizrahi electoral list received 6,234 votes in Courland and both of the Nurok brothers were elected, while “Agudat Yisrael” received only 163 votes there.

In the city of Riga, most of the votes went to “Agudat Yisrael.” Without doubt, this was due to the great esteem for Mordechai Dubin who was at the head of this electoral list. He was renowned in the city for his energetic advocacy and for his warm Jewish heart that was willing to help the religious and the non-religious alike. Thanks to the massive support that they received in the two largest electoral precincts with Jewish voters, “Agudat Yisrael” was able to send two representatives to almost every Saeima. So in addition to Dubin, mentioned above, they appointed Reuven Wittenberg or Simon Yizhak Wittenberg.

Due to fundamental differences of opinion, the Jewish representatives in the Saeima were never able to establish a Jewish faction or any other framework for cooperation. Generally, the Jewish representatives in the Saeima presented a unified front only when the Saeima dealt with matters that were considered to be especially important for the entire Jewish population, for example: the law of citizenship (which was finally passed only in 1927); removal of restrictions to allow Jewish refugees to return from Russia; anti-Semitic behavior of officials; physical abuse of Jews.

One problem, of special importance to the Jews, occupied the Latvian Saeima many times. The problem was focused on the independent management of the Jewish schools and the question of what would be the language of instruction in them: Yiddish or Hebrew. The most incisive opposition to Hebrew as the language of instruction came from Dr. Noah Meisel, the Jewish representative of the “Bund.” Politically and generally he was connected with the faction of the Latvian social democratic party. When the vote concerned economics, social issues or preservation of democracy, then Matityahu Lazarson (the Zionist youth representative) joined forces with the left bloc in the Saeima. It was not without reason that he and Noah Meisel were among those arrested immediately after the Ulmanis revolution of May 1934. “Agudat Yisrael” generally supported the right wing parties. And they in turn repaid “Agudat Yisrael” on various planes. The government awarded a most important status to this party after the right wing revolution of Ulmanis. Due to legislative difficulties, to differences of opinion between the representatives of the national minorities and to internal differences within the minorities themselves, the autonomy of the national minorities in general and of the Jewish minority in particular was not implemented. It was supposed to rest on a network of communities in every place in the land where the Jews lived. The communities themselves were not granted legal recognition, but in spite of this the government recognized them “de facto” as the local Jewish representatives. In contrast to this, the autonomy of cultural and educational institutions was implemented, right from the establishment of the Latvian state. The center of this autonomy was in the system of schools of different types and different levels that were scattered all over the land.

|

|

Seated right to left: Ms. Schneiorson, Rachel Donda, Sarah Gideon, Jacob Cohen. Standing right to left: Zvi Tolowitz, Sheinfeld, Gamzu, Zvi Sheinin, Kaminov, unidentified man, Ms. Tolbowitz. |

|

|

(Photographed in the 1930's) |

|

|

In the lead: A. Kalman, Y. Denenhirsch, Y. Schlesinger. |

While the Jews were free to participate, at least in proportion to their numbers in the population, in the legislative institutions and in the autonomous cultural field, things were different in the various institutions that actually carried out activities on behalf of the state. It is true that the Jewish activist, Prof. Paul Minz, was appointed to the post of state comptroller at the outset of independent Latvia, but he served in this position for a short time only. The first foreign minister, who was later prime minister for two terms, was Zigfrīds Meierovics, a man with Jewish ancestry on his father's side. When the right wing government lead by Alberings was brought down in 1926, the state president delegated the task of forming a new government on a Jew, Rabbi Mordechai Nurok the representative of the “Mizrahi” party. At that time, Nurok lead the democratic minority faction (comprised of 2 Jewish, 3 Russian and 2 Polish representatives). This event was of considerable political and social significance for the status of the Jewish minority in Latvia and made a resounding impression outside Latvia.

This was the total extent of integration of Jews in the upper echelons of state government. Jews did not reach the upper echelons in the field of municipal government either, even though they comprised nearly half of the population in some centers. One exception to this was the city of Varaklāni, where two democratically elected Jews served in the capacity of mayor. In general, the government under the influence of the peasant organizations tended to blur out the Jewish character of such cities. They achieved this by enlarging the administrative area of the city and annexing the surrounding peasant population to the electorate. This diluted the proportion of Jews, Russians, Poles and other minorities in the city population. Another method used to Latvianize cities and towns and reduce the proportion of minorities was to station army units there and include the soldiers in the municipal electorate of the city or town.