|

|

|

[Page 253]

written by Abraham Wise (Tel Aviv)

[from page 7]

With the destruction of the temple, the Torah became the only treasure of our nation. A new tradition arose in the land of Israel, the writing of Torah Scrolls in the names of the departed in order to bless their memory and eternalise them in heaven.

Those who could not afford a scroll to be donated to the synagogue could at least donate a new prayer book. It never occurred to any congregation to memorialise a whole community, as they all believed in their survival until the coming of the Messiah and the Reincarnation of departed souls.

Not only did they believe in their own redemption by the ingathering in the Land of Israel, with song and poetry, but also that their departed brothers would arise.

But, behold, the great destruction occurred and took with it thousands of thriving communities and millions of Jews, and obliterated their names under heaven. And now the survivors ask how they may revive their holy institutions and create a life in Israel and the remainder of the Diaspora.

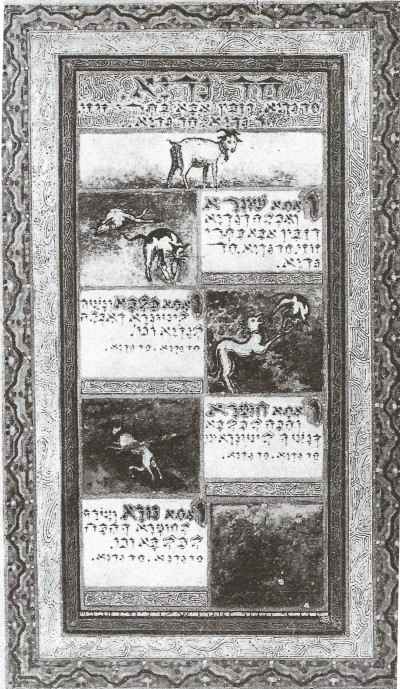

David Davidowitz found a way to eternalise his community by writing the Pabianice Hagaddah, something that took him three years to execute. Besides the Bible, there is no other book as popularly accepted as the Passover Hagaddah. It is regarded as a most important document not only by Jews, but also by the whole world.

The Hagaddah was written over thousands of years, concluding during the period of the Second Temple when the saying “you shan't add or erase anything from it” was coined.

But the creativity of the Pesach Hagaddah never stopped; as the saying goes, “from then on Moses and the Children of Israel shall break out in song” on the banks of the Red Sea, and until today the embellishment of this event has never ceased.

Every generation added its own chants, illustrations and renditions “and he who extends the story telling is commendable”. It was not only intended for old or wise men, but also for women, children and even the youngest of babes, and it is to be uttered preferably in the holy tongue, but was also translated into all the languages of the world. It was intended for all levels of Jewish Society, and for the whole of humanity as an historical document.

See for yourself this wonderful book, which is only used once a year [in Israel] or twice in the Diaspora, and has more editions than any other Jewish Book. Every generation in every Diaspora community needed its own interpretation as “in every generation, a man must see himself as if he himself was freed from Egypt”. We know of no book, other than the Passover Hagaddah, where such expense and toil went into its illustrations and design. The Hagaddah is the one main survivor of Middle Ages manuscript artwork.

[Page 254]

Every museum and art gallery in Europe and the U.S.A boasts its ancient Hagaddah Collection. The Jews of Serbia, Mentova Daramestz, sold the most beautiful Hagaddot to world famous art dealers, and that became the testimonial of the would–be–forgotten, doomed communities. The descendants of those congregations refer to their birthplace using the various Hagaddahs as keepsakes.

Our first illustrated Haggadah originated a unique art form in the thirteenth century in Germany, France, Italy and Spain. With the invention of the printing press, wooden covers were created in Prague (1526) and etched metal book covers in Holland (1695 – Amsterdam).

This glorious artwork reached its peak in the eighteenth century. Afterwards, copies of the ancient artwork were stereotyped into newer Hagaddahs. It is only in recent times that new creative attempts have been made by notable artists, and they have produced very successful results.

Amongst all the modern makers of Hagaddahs, two Polish artists attached to the Jewish Community are notable. One is Arthur Szyk who was commissioned by the city of Lvov, and the other is David Davidowitz, who devoted his Haggadah to his birthplace Pabianice.

Even though both Haggadahs are enlightening, there are considerable differences between them. Arthur Szyk, a talented, sophisticated artist, was influenced by the Christian illuminated manuscripts – not much to our liking. David Davidowitz on the other hand produced the printed front and illustrations more to our taste. This artist was brought up in a Hebrew culture from babyhood, went to a Jewish cheder in Pabianice and then to the Polish high school there, and graduated from Strasburg University in Engineering.

Dr Kane Swartz, the renowned art historian, commended David Davidowitz in his book “The New Jewish Art” (Tel Aviv 1941), particularly for the established Jewish version of modern art which distinguished him from his contemporaries. He absorbed much of European culture into his work and achieved an east–west cultural synthesis.

He has been discovered in Tel Aviv as an original great artist, following the sculptor Nacham Aronson's recommendation, and he has been made an honorary Jewish art analyst beside his daily profession as an engineer in the Tel Aviv City Council. He has been successful in both roles, which are undoubtedly complementary to each other.

An artist with a keen eye, as he is described by Ch. Orian in “Haolam”, he looks deeply into the essence of every Jewish creation. He shows integrity in his means of expression. He did not adopt the French style of his tertiary education but remained a Jewish artist.

To be honest, we were not used to his colourful illustrations, so different from the black and white versions that we have been used to in printed books for the past five hundred years. However, looking at the sixty brightly coloured plates in the Pabianice Hagaddah, we fell in love with them, as Davidowitz knew how to choose colours. These are not the gay colours of the Arthur Szyk Hagaddah, typical of the Catholic countries and illustrative of sin, which is absolved by their priests after confession. These colours would produce disharmony on a Jewish canvas. Davidowitz uses dark, serious colours reminiscent of Rembrandt and the Dutch school of art.

[Page 255]

They suit the grey life of the Jewish exile experience. For the first time in centuries here is proof of the fact that it is possible to embellish a Jewish book with colour: colour that won't obliterate its originality but will make it seven times bolder.

Every miniature in the book is bordered by very expressive and graceful authentic frames. The French critics gave much praise to these lovely artistic encasements describing them as “eastern”. But what they failed to understand is they result from a thousand years of evolution of a culture in a European diaspora, rather than from a stable culture concentrated in the Far East.

His art is influenced by a thousand years of Ashkenazi culture and by every country where Jews have lived and spoken Yiddish, a successful and very typical expression.

The latest innovation of the Pabianice Hagaddah is the Hebrew alphabet. There are two opinions regarding the origins of the alphabet. Some think it originates in the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs. Others think that it started with the cuneiform of the Babylonian and Sumerian cultures. Davidowitz is of the second opinion since he actually carved each letter rather than drew it, each letter made up of various parts.

This Hagaddah is a first example of its kind and its form will be discussed widely quite apart from its story of the Exodus.

The main quality of the work is not in its many innovations but, on the contrary, in the continuity of the ancient glorious tradition of authors, editors, copiers and printers, that has survived to this day.

To date the Pabianice Hagaddah (1956) has not been printed, as no printer known can reproduce its original colour scheme. It is, therefore, a memorial manuscript, remembering the Jewish Pabianice which was wiped off the map of Europe with the rest of European Jewish communities. Thanks be to this sole family survivor, who in his Hagaddah has so beautifully eternalised the memory of a family and a community who perished for the sanctity of Hashem.

[Page 256]

|

|

[Page 257]

|

|

written by Moshe Cohen

[from page 75]

|

The Gerre Shtibl was the “Fortress of the Gerr Chasidim” and its assembly of prayers was known as “Students of the Torah and of good deeds”.

In my youth, when I arrived at the home of prayer at 5.00 a.m. on the coldest day of the year in order to study the weekly portion of Shachris, there were already many learning partners present, studying and chatting loudly. The “Blitz Lights” were on, the fireplace was stoked and lights and heat filled the whole place; outside the temperature was freezing and it was snowing, the ground covered in flakes.

Most of the participants were tradesmen, shopkeepers, industrialists and merchants who, during the working day, would be working to support their families. At daybreak, at 7.30 or 8.00 a.m., they would stop studying and go to morning prayers. The young men, the rabbinic students and the teenagers would continue studying till 9.30 a.m. and then proceed to morning prayers. Only when these ended did they return to their homes to have breakfast. At 11.30 a.m. they returned to their studies, which went on until 2.30 p.m. At 4.30 p.m., after lunch and rest, they went back to the study house, later to be joined by the businessmen. This continued until 10.00 or 11.00 p.m. Among the young men were:

Moshe, the son of Leizer Rittkopf,Shalom, son of Hesinich Krieger,

Eliyahu, son of Chaim Kabitkovski,

Moshe–Leizer, son of Chanoch Zederbaum,

the young man Yivlech, a diligent student,

and Joseph, son of Moshe Zimberknop (who presently lives in Tel Aviv).

They would study Torah until the early hours of the morning. This is neither the time nor place to describe how these lessons were conducted, in the absence of an oversighting teacher or a clear methodology.

When they graduated from their studies in order to get married, or to enter the workforce, or join other Yeshivas at the various towns in Poland or Lithuania, many remained as mentors for the younger people.

[Page 259]

This gifted group qualified and became rabbis and some even went on to teach or study in Israel. Even the most enlightened of them kept wearing the traditional garb.

The winds of change and the Enlightenment, that over many years influenced and changed a great many Polish Jews, hardly entered their consciousness. I emphasise this because, with Pabianice only a fifteen minute tram ride from Lodz – the largest textile industry city in Poland – many were not immune to these changes. However most of the population of Pabianice was orthodox and, despite the growth of the Zionist movement, they continued to oppose change.

Even the Agudat Israel, whose German counterpart became Zionist in 1911, was regarded with suspicion by the ultra–orthodox, who believed in the slogan “Innovation in Torah is forbidden”.

At the onset of World War I in 1914, the Jewish population suffered a great economic slump – especially in the cities where the main industry was textile production. All communications with greater Russia ceased. However, the German invasion of Poland had a positive cultural influence on the Jews.

The Labour socialist movement's younger men started running various underground activities. The Workers of Zion and other active Zionists began organizing a dynamic new alternative group. Eventually, they rented a room on Warsawska Street where people came to hear the latest war news and news from Israel, read newspapers, play chess, and listen to lectures, particularly about Zionism.

The Orthodox students were too frightened to attend these events, of which their parents disapproved. However this surge of new ideas also penetrated the cheders and on the second day of Shavuot, in the year 1915, a secret meeting was held at 33 Kosziousku St, in the Pozonowski's home, attended by my religious friends, to see what could be done about this situation. The members who attended this meeting were:

Yosef Zimberknopf,Itzchak–Meir Morgenstein,

Yosef Neidk,

the writer of this memoir

and another dozen young men.

We decided to start a group to be named Chibat Zion [Love of Zion], the idea being to insinuate our ideas into the religious groups. But Rabbi Mendel Reichbart, the father of the president of the group, discovered our plans and inconsiderately burst into the apartment where we were meeting, screaming, “What is this? What are you doing here? Plotters, leave this place immediately. My son will be punished for this deed in good time.”

News of this incident spread quickly and turned out well for our group as, despite opposition and name–calling, many people joined us. It now became the Religious Zionist Movement of Pabianice and worked in liaison with the Lodz and Warsaw Mizrachi Movement. We would have regular meetings and send our most persuasive members into the religious cheders. The religious–Zionist group respected us as well, and became members of our organisation to the detriment of our opponents.

[Page 260]

During one of the meetings of the temporary committee, we decided to appoint Yosef Zimberknopf to lecture about the “Mizrachi Movement”. He invited a noted professor, Hazchak Dibkin, now living in the U.S.A., to give a talk on the theme “What is Mizrachi?” For the occasion, we hired a hall called “The Genebart” and even received permission to do so from the Polish authorities, who were not as opposed to our ideas as the Russian regime.

A few hundred men and women attended this lecture; this was the first time many of the attendees had heard a Zionist lecture from a highly intellectual religious figure. It was a very successful evening, although it was disparaged the next day by the ultra–orthodox factions.

At the conclusion of Chol Hamoed Succot, on the eve of Shmini Azeret, at the prayer gathering in the Gerre Shtibl, people began whispering when the Hakafot [circling around the Torah] began. For some reason the service was delayed, and when the congregation began complaining a few zealots jumped up and screamed, yelling, “We will not pray with these criminals!” The shouts and screaming of abuse between the two groups did not cease until late into the night. Finally, the crowd went on its way not having said Ma'ariv [the evening prayer]. Without the traditional Hakafot the Festival ended very dismally. The next morning there wasn't even one Minyan [quorum] to pray for rain from the tens of previously established Minyanim.

At night, the night of Simchat Torah, we managed to resurrect many Minyanim because the news spread that the shtibls were “conquered” throughout the city. Those who identified with us streamed into our prayer groups, even from the “old city”. Even young men who were not regular attendees joined in to celebrate our “victory”.

In contrast to the previous evening, this night was celebrated with song and dance and we were glad to find that we weren't alone: even the notable rabbi Heinrich Vigdorowitz joined our ranks. However, he also continued to pray at the Gerre Shtibl in Neischtat [The New City]. He was a son of a prestigious rabbi and a descendant of a great dynasty of the Gerrs in Poland. He promised to support the renewal of the lease for our prayer group, and even invited us to a celebratory drink [Mashke] that is traditional on Simchat Torah. He inspired us not to give up and encouraged us to go on in the belief that soon many more would join us.

The Gerre Shtibl survived the whole winter, though its former zealot members would never set foot in it. There were attempts to make amends and we invited back the zealots who had left, so as to make peace. But they refused and rented their own shtibl. Oddly enough, later on many of their sons and daughters became leaders of our movement. The previous shtibl was now called “The Mizrachi Shtibl”. We organised courses and dealt with Mizrachi problems and Torah education.

R. Yosef Zimberknopf was our leader and our liaison with the other Mizrachi centres in Poland. With the passing of time the centre was the lead educational centre not only in our city but in the whole region. The zealots made several attempts to retrieve their shtibl but to no avail. There was even an attempt by them to bring on a public trial under the Polish authorities, and to the embarrassment of the Jewish population, but their efforts were in vain.

And so ended an interesting chapter in the history of Mizrachi in our city.

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Pabianice, Poland

Pabianice, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 27 Jan 2017 by LA