|

|

|

[Page 143]

Ritro Labor Camp

I arrived at the Ritro labor camp dressed in summer clothes the way I left the Roznow labor camp in the morning for the selection at the ghetto of Sandz. All my belongings including money and papers and papers were left at the Rozinow camp. The announcement about the departure for Sandz came after we had left the barrack and were on the way to work. The Germans did not permit us to go back to the barrack and get our belongings. Of course, there were some Jewish workers who arrived with back packs that contained all their belongings. I had nothing and could not complain. The Germans appointed Kuba Fuhrer to be in charge of the Jewish forced laborers. He selected as his assistant, his friend Awraham Segulim.

The wooden barrack contained two–tier bunk beds that had mattresses of hay or sawdust. Most of us received two blankets. Food was a serious problem at the camp. I worked with a Polish youngster at cutting leftover pieces of wood. The cutting was done near the living quarters; there were no guards there. There were German armed guards who belonged to the company. The supervisors of the sawmill were Germans and the place belonged to the German company known as “Hubag.” All section chiefs were former soldiers who were disabled during the war. We worked 12 hours a day and received two meals per day. In the morning we received a cup of coffee and a slice of bread. At noon, we received a bowl of soup and whatever floated in it. At the morning break, we sat with the Polish workers who brought food from home that consisted of cooked potatoes, country bread, milk or sour milk. Since our breakfast was practically non–existent, we started to trade with the Poles, clothing for food. Shirts, pants socks were bartered for cooked potatoes, bread and milk. A black market of sorts developed in the camp between the Jewish forced laborers and the Polish workers.

We ate lunch in the big mess hall. I was lucky since one of the kitchen workers, Moshe Kriser, was from Sandz and knew me. The latter used to slip a cooked potato into my bowl of soup. The managers and supervisors also ate in the same mess hall but their section was closed off. Still, I waited whenever possible to sneak into that section to finish the food that was left on the plates by the Germans. With time, the food situation improved. We received three meals per day. On Sunday, the sawmill was closed but the Jewish forced laborers were forced to load sections of finished wood barracks aboard the train that headed to the front for the German army in the east. The railway station was opposite the sawmill. Attempts were made to establish contact with the few remaining Jews in Sandz. Some attempts succeeded. Contact was established with Yehoshua who was a fruit dealer who had survived the liquidation of the ghetto of Sandz. He employed a Polish maid who traveled between Sandz and Piwniczena. She lived in Piwniczena and worked in Sandz. Yehoshua began to send letters, money and even some packages to the Jews in the Ritro labor camp. Of course, she also provided the latest news regarding Sandz and the few remaining Jews there. Some of the money that was sent from Sandz disappeared along the road. At the time, one of my surviving uncles sent me some money but I never received it. To this day, I do not know what happened to it.

Toward the winter of 1942, the Jewish labor leader Fuhrer gave me some winter clothes since I had left everything in the Rozinow camp. Fuhrer wanted his Jewish workers to be content and not to create problems for him. The Ritro camp was not far from the hamlet of Ritro where there were no German soldiers or Gestapo men. It was easy to escape from the Ritro labor camp but the Jewish supervisor watched us like a hawk. He was afraid that someone might disappear and we would all be shot, including him. So he watched us very closely and tried to make life bearable.

One evening I worked the night shift with the Polish youngster. I was very tired and wanted to close my eyes for a few moments. I asked my Polish partner to keep his eyes open and if he saw a guard to wake me. He also fell asleep and the German guard making the rounds saw that I was missing. He started to look for me and found me asleep. He took me straight to the German commandant of the camp who ordered that I be given 25 lashes on my backside. The lashes were extremely painful but I survived. I could not sit for days on end since everything was raw. My big tragedy was the fact that I lost my position as a wood cutter inside the building. I was now assigned to work outside in the cold winter with no real warm clothes. My new job consisted of collecting used wooden planks and boards. I had to clean them and dunk them in large bathtubs containing chemical solutions that coated them against pests. The water solution was usually red.

I still remember some of the Jewish workers who worked with me at the Ritro labor camp.

Nechemia Sheingut

Moshe Dawid Laor

Yeshayahu Bergman

Zalman Fefer

Iziv Kaempner

Wolf Shimel

Moshe Krizer

Menashe Wolf

Romek Gut Hollander

Asher Brandstatter

Motci Blauzenstein

Berek Hershtel

Awraham Segulim

Kuba Fuhrer

Mordechai Lustig

There were of course many more Jewish workers but I do not remember their names.

Flugmotorwerke in Lisia Gora, near Rzeszow

Suddenly, on February 23, 1943, we were told that we would be leaving the camp. Officers of the German air force came and took us to the railway station where we boarded a freight train and headed to an unknown destination. We traveled for hours and finally reached our destination. It was a former Polish air force installation. The letters PZL were still visible and stood for Polskie Zaklady Lotnicze or Polish Air Force Warehouses. The place now belonged to the German air force where there was a “Flugmotorwerke” or engine plane factory. It was located in Lisia Gora, near the city of Rzeszow. The aeronautical plant was operated by the German company Daimler–Benz. The place produced engines for the “Junker” planes.

We reached the camp at an early hour in the morning. We were received by two Jewish supervisors. One was named Bener and he was from the city of Przemysl in Poland. The name of the second one escapes me. We immediately received bowls of hot soup and bread. We were also accommodated in the barracks where there already were about 200 Jewish workers. The workplace had many metal machines. The living places were long halls with bunk beds that contained mattresses with hay. Our group was assigned to study theory and work on the metal machines.

The food situation was good. We started the day with an inspection of cleanliness, then a head count and finally we left for our workplace where we would spend the next 12 hours. There were two shifts. We also had to tend to the gardens around our workplace.

I was lucky that I found a big coat that would come in handy later. The work at the place was very hard and intensive. We worked and studied long hours. The place also had a policy of writing down the names of workers who broke or damaged instruments. The list was called the blacklist and was kept with precision. The first shift would wake up, wash and receive breakfast that consisted of coffee and bread. Then the head count and we headed to work at about 10 o'clock. We remained at the workshop until 10 o'clock at night. The night shift had difficulty sleeping in the day for there was always noise or other disturbances that prevented the workers from sleeping. During the month of March, I worked the night shift. I suffered from boils that prevented me from sleeping. I worked then with Wolf Schimel who was originally a dental technician. We operated this big metal machine that made specific metal plates that were fitted with big screws. I barely managed to stand on my feet. I told Wolf that I must get a couple of winks since I did not sleep in the day and I had the boils on my back. Wolf said: “Go ahead and rest I will watch and would wake you if the Ukrainian guard reaches the area.” I sat down on the lowest step of the metal machine and fell asleep. Of course, Wolf fell asleep and the guard caught me sleeping. The Ukrainian guard caught me sleeping and started to shout and beat me mercilessly. He then dragged me to a water faucet and let the ice cold water run over my head. He held my head under the running water and I felt that my head would explode from the cold. Finally, he let go but he placed my name on the blacklist. I continued to work at the same machine. Ten hours of work and two hours of theoretical study and mathematics.

One day in April 1943, while working in the garden surrounding the barrack, I heard the announcement that all people on the blacklist are hereby ordered to leave everything and report. I left my work and joined a large group of Jewish forced laborers who were already assembled outside the workshop. I also saw the fully

|

|

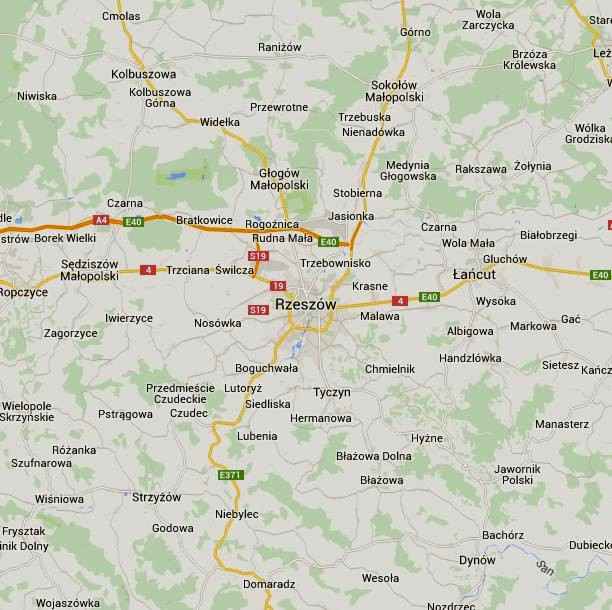

| Map of the city of Rzeszow or Reishe |

armed SS men who waited in the area. I thought to myself, where could they take us, what would be our future? Would they finish us somewhere over here? We marched out of the camp and began to march We marched and marched and finally entered the ghetto of Rzeszow.

Rzeszow or Reishe in Yiddish is located in southern Poland about 150 kilometers east of Krakow. Jews lived in the city since the 15th century. The city's Jewish population reached about 15,000 people in 1939 or one–third of the total population of the city. The Germans immediately started to harass the Jewish population. The crescendo of persecution of the Jews reached the peak in June 1942 when the Jewish population reached 23,000 souls. The ghetto was packed and poverty was rampant.

The process of concentrating the Jewish population of the region started as early as March 1941. All the Jews from small villages were ordered to move to ghettos in the nearest towns. They had to leave behind almost all their property. Jews moving to the Tyczyn ghetto were brutally beaten; all were robbed, a number killed. On 25–26 June, all Tyczyn ghetto Jews were resettled in the Rzeszow ghetto. Again, the march was accompanied by brutality and murders. A number of Tyczyn Jews were executed at the local Jewish cemetery. Jews living near Kolbuszowa were forced into the ghetto there in autumn 1941.

This ghetto was closed in February 1942. In Sokolow Malopolski the ghetto was formed in April 1942. At the time of the ghetto's liquidation in June 1942, 3,000 Jews lived there. During the resettlement to Rzeszow, 28 persons were killed. Most of the Jews from the ghetto in Glokow Malopolski were moved to Rzeszow in early July 1942. Jews concentrated in the ghetto of Strzyzow were resettled to Rzeszow on April 26 and June 9,1942 and those Jews of Blszowa on June 26,1942.

By the end of June 1942 all Jews from the smaller towns of Majdan, Kolbuszowa, Czudec, Niebylec and Staniszewska, together with some from Lancut, Sedzszow Malopolski and from small villages near Rzeszow were forced into the ghetto of Rzeszow. As a result, the population of the ghetto rose to almost 23,000 people.

|

|

| Jews of Rzeszow being driven to the train station (Yad Vashem Archives) |

In June 1942, the responsibility for the entire Jewish population was transferred from the administrative authorities to the police and SD (security police). At the beginning of July, the Germans imposed a penalty on the Rzeszow ghetto of 1,000,000 zlotys, to be paid by its Jewish inhabitants. Between July 7–19, 1942, it is estimated that 20,000 were deported to the death camp of Belzec where they all perished. Yet there were still about 4,000 Jews in the ghetto of Rzeszow, for the Germans kept moving Jews from all the ghettos in the area to Rzeszow. We assume that most of the original Jewish inhabitants of Rzeszow were no longer alive when Mordechai Lustig arrived in April 1943 in Rzeszow from Gora, near Rzeszow.

|

|

| Jews of Rzeszow being forced into deportation train at the Staroniva station (Yad Vashem Archives) |

Rzeszow had two ghettos: ghetto east and ghetto west. The ghettos were separated by a road that led to the eastern ghetto where there was no work. Both ghettos were surrounded with barbed wire and under the administration of the Judenrat and the Jewish ghetto police. The eastern ghetto had workshops that provided employment to workers. Many of the Jewish workers worked outside the ghetto and came in contact with the Polish population that sold them food that they brought home. The western ghetto was sealed and there were very few employment opportunities. If you did not have money, you could starve. Our group was taken to the western ghetto. The Judenrat officials assigned us – Shia Nagel, the two Kahana brothers, myself and a few other people whose names I no longer remember – to various buildings and apartments. I was assigned to an empty apartment where a Jewish woman and her two children had just arrived from the liquidated Krosno Jewish community. I went to sleep on the floor and covered myself with the big coat.

The Judenrat assigned me to work on collecting and restoring bricks and maintaining sewer holes. I was given food that consisted of a bowl of soup that looked like carrots and a piece of bread. This was the food for the day. I realized that this was a starvation diet and many Jews in the ghetto died of starvation. On the other hand, if you had money you could eat at the restaurant like the Jewish policemen who ordered rolls with soup and eggs or potato puree with onion sauce. One day, I received a postal card from my two uncles, Moshe and Awraham. They informed me that they were alive and were in the ghetto of Tarnow. I was very pleased with the news. Following the end of the war, I looked for my uncles but did not find them. A childhood friend named Zvi who was in the ghetto of Tarnow told me what happened. My uncles decided to escape from the ghetto of Tarnow. They were spotted and shooting ensued. Both uncles perished.

Occasionally the Jewish police would seize Jews and send them to terrible places like Huta Komorowska or Bieszadka where the survival rate was very small. Whenever there was an action I hid very well in the septic sewer system where there were large manholes along the road. Yossef Niemiec and myself were busy unclogging the sewers so that the standing waters would disappear. We planned so that we advanced slowly toward the fence of the western ghetto. There we received food that consisted of soup and bread. People were standing at the entrance gate of the western ghetto but the Jewish police would not let them enter. Of course, black market operations took place along the fence. On occasion I managed to get some food and give it to the hungry people at the entrance gate. But this solution could not last.

I knew that the Judenrat had posted ads on the local bulletin board in the western ghetto that asked people with skills like carpenters, plumbers, to sign up for jobs. The jobs were located at the Skarzysko concentration labor camp at Juleg. People who signed up were permitted to enter the western ghetto and received food for about 10 days. This treatment improved tremendously the appearance of the workers. I asked someone to do me a favor and place my name on the board. I was soon called to report to the western ghetto. I barely spent one day in the camp when I came down with typhus. The epidemic raged in the camp. I had fever and was unable to move. My case was soon reported to the Jewish police and I was soon shipped back to the eastern ghetto to the hospital. I remained at the hospital for one month and thanks to the good care of a nurse who provided me with a constant flow of tea, I managed to return to myself. About 800 people of a population of 2,000 died of typhus at the ghetto. Following my discharge from the hospital, I was very weak. I approached a restaurant owner and told him that I would bring water to the restaurant and peel his potatoes for food. The water pipes to the restaurant did not function. The owner agreed and I worked for a short time as a water hauler until my strength came back to me.

You are probably wondering how a restaurant could function in the ghetto where there were few food supplies and the guards were instructed to prevent food from entering the place. The answer was very simple. The ghetto was surrounded by fences and Polish policemen patrolled the outside fences. But Polish youngsters managed to find loopholes and with the help of strings managed to deliver to the ghetto an ample supply of food that enabled the restaurant to provide rolls, eggs, potatoes, flour, sugar and onions.

My situation was getting hopeless. Then I met Yossef Niemiec who was with me in the engine plant. We discussed our situation and concluded that we must get to the western ghetto in order to survive. We decided to approach Lazarowicz. He arrived in Rzeszow with a transport of Jews from the area of Lodz in November or December 1939. He worked with the Jewish police. He was the official undertaker of the ghetto. He had a license, a horse and a cart. He was also permitted to travel outside the ghetto. We approached him and begged him to smuggle us to the western ghetto so that we could register for jobs. This was a very complex situation but we managed to get to the western ghetto. Lazarowicz even gave each of us 500 zlotys so that we could have a good meal and appear decent in the western ghetto. We entered the ghetto and signed up for work. Meanwhile we received food and rested for 10 days. Then the S.S. men came and took 50 of us. We climbed aboard trucks and proceeded to the labor camp of Pustkow near Debice.

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Nowy Sącz, Poland

Nowy Sącz, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 07 Nov 2015 by JH