|

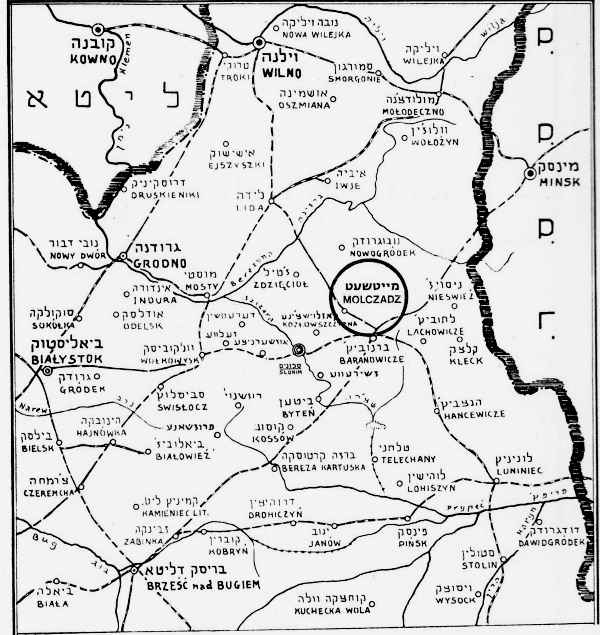

Map of the region, with the community of Molchadz in the center

|

[Page 25]

[Page 26]

|

|

| Map of the Region Map of the region, with the community of Molchadz in the center |

[Pages 27 - 41]

Translated by Semadar Siegel and Esther Mann Snyder>

The name that is used by the residents of the city and surrounding vicinity is Maytchet. The name that appears on the official documents from the era of ancient Poland as well as the maps of modern Poland is Molczadż, whereas in Russian it is Моўчадзь. This name came from the Molchad River, which passes through the region and flows into the Molchadaka River.

In general, cities and villages were named after geographical locations or historical people or events. This was not only for the purposes of identifying the area, but also to perpetuate it, such as the case with a historical event, a national hero, the name of institution. However, not every city merits a splendid family tree that denotes an important historic event. For the most part, a settlement is named for the river upon whose banks it was founded, such as Vilna for the Vylia River, Dvinsk for the Dvina River, and Maytchet for the Molchad River, which is a left tributary of the Neman. In a district with a long history, it would sometimes happen that various tribes and nations would live there in older times, and as their language is forgotten, so would be the meaning of the names of the rivers, mountains, and the like. Names of cities and towns that were called by their names have now completely lost their meaning, and are only decipherable by historians.

This was indeed the historical-geographic and demographic situation of the near and far area of Maytchet, from which it drew its livelihood and spiritual influence at the time of its founding and during its existence. During ancient times, this location was a meeting place of wandering peoples -- Russians, Byelorussians, Lithuanians, Tartars, and Poles. Even those who would travel from afar, wandering through the area at that time, would not pass over this region. These different tribes

|

|

| General view of Maytchet |

[Page 29]

continually fought over who had the right to settle and govern this place. Everyone left behind a remnant of their presence in the cities and the settlements, such as fortresses or castles. And each thing, by their name, represents the times and places from whence they came.

As has been stated, Maytchet is the name used by the Jewish residents, as they used to give such names in every place, and therefore does not serve as a source for research. However, the old original name Molchad has a definitive local ring, whose old meaning stems from the river that passes through the area.

We should note that besides our city and the river we mentioned, there are other settlements, including villages and farms, where the name Molchad is noticeable in the name. These include Molchanuff, Molchani, Molchanovka, Molchanovo, Molchnaska Huta and Molchanska Luka, and others. This is aside a string of names with the root Milchan. The article of Molchani in the Geographic Dictionary of the Kingdom of Poland theorizes that these names form a historical link with the ancient Slavic tribe called called Molchan or Milchan. which is mentioned by chronologists and historians.

The elders of the town tell the following joke that used to be widespread in the area: A high ranking Russian captain was passing through the area and did not know about the place and its name. He sent an assistant to ask the residents of the city about the name. When the aid came back the captain asked, “What is the name of the city'” He answered “Molchat,” which in Russian means “be quiet.” The captain slapped him on the cheek and shouted, “I asked, what is the name of the city!” The assistant responded once again, “Molchat”…

b. Sources regarding the Early Period of the TownA major methodology utilized by researchers of Jewish history and communal life during the period of autonomy of the Jews of Poland and Lithuania is to peruse the ledger, which is the well-known “Pinkas” of the Council of Four Lands. This is known as a reliable source for information and details in this area. With regards to a Lithuanian city such as Maytchet, the most important Jewish source is the Ledger of the Council of the State of Lithuania, which is a book of minutes of the autonomous council of the Jews of Lithuania, which in the year 5383 (1623) separated from the Council of Five Lands, which then became known as the Council of Four Lands. This ledger is a reliable source of information on the Jews in the community of Lithuania, from the perspective of religious, economic activities, and family life, etc.

At the first meeting of the autonomous council in 1623, the Ledger of the Council of the State of Lithuania opens with a split into three regions -- Brisk [Brest], Horodna [Grodno], and Pinsk, as well as with the division of the regions into central communities and smaller communities that were depended on the central communities with regard to the imposition and collecting of taxes. According to this division, Maytchet is listed together with all the small towns around it, which were directly subordinate to the community of Slonim in the district of Brisk regarding to the payment of taxes and other matters. Furthermore, in the municipal and administrative edicts of Slonim, which was the regional city in that period,

[Page 30]

Maytchet is also mentioned as subordinate to it for administrative matters, intercession with the authorities, etc.

Jewish encyclopedias are an additional source of information on the Jewish communities. They generally contain a number of lines on each settlement according to its size and importance. Nevertheless this information is sketchy and is very general. The information below appears in the Brokuaus-Efron Jewish Encyclopedia written in Russian:

|

|

| Maytchet, early period |

“Mołczadż Моўчадзь during the time of the Rzeczpospolita was a town in the district of Slonim. In 1765, 369 taxpayers lived in the community.

Today it is in the region of Grodno, which is in the district of Slonim. According to the census of 1847 the Jewish population of Maytchet was 340 people, and according to the census of 1897 the general population was 1,733, of which 1,188 were Jews.”

It goes without saying that the general encyclopedias, rich in various entries, tend to dedicate their entries to central cities and places of historical and political importance, skipping completely over smaller communities. On the other hand, the various lexicons and geographical dictionaries, whose purpose is specific and whose scope is restricted to a specific country, pay equal attention to a city and a village, a railway and a roadway, and even the location of a small flourmill on the banks of an unknown river, without skipping

[Page 31]

over anything. This is what was written regarding Maytchet in the Dictionary of Geography of the Kingdom of Poland [Slownik Geograficzny Krolestwa Polskiego], which was published in 1889 in Warsaw (in Polish):

“Molczad is a town situation on the Saratowa River, where it flows into the Molchadka River, in the district of Slonim; which is SE of it alongside the Vilna-Romania railroad. The total population is 1,128 (specifically 524 men and 604 women), of which 702 are Jews. In 1654 Maytchet was destroyed in a fire and the people in the town were released from paying taxes and civic duty for four years. In 1879 two thirds of the city burnt down.

The environs around the city were hilly with sandy soil and it was sparsely forested. It was a stop on the Vilna-Romania rail line (officially Molczad). There was a post office and a telegraph line between the railroad stations of Navolania (25 verst)[1] and Baranovichi (25 verst). It was 162 verst from Vilna, 63 verst from Lida, 189 verst from Pinsk and 301 verst from Kobrin.”

c. Settlement of Jews in LithuaniaThe Jews came from different areas of the Diaspora, and from different expulsions, and settled in Lithuania in the 14th century. The liberal Lithuanian ruler Gediminas (1336-41), who expanded the borders of his country to the Nieman and Bug rivers through his conquests and victories, was welcoming to settlers from outside, among whom were many Jews who were needed for the development of his large but still undeveloped country.

The liberal treatment of the Jews continued with full force with Gediminas' grandchild Witold (1430-86), who even granted the Jews special, far-reaching privileges in order to encourage them to build up and develop his country. Thanks to the humane treatment of these two princes and of the Lithuanian population, who were still pagans until the second half of the 14th century and had not yet been infected by the venom of Christian anti-Semitism, many Jewish settlements developed. The three largest Jewish communities were Brisk, Grodno, and Troki.

However, as was always the destiny of Jews of the Diaspora, after approximately 200 years of relative tranquility and after they put all their energy and blood into the building of a country that was not theirs, history repeated itself. “A New King Arose,” “Let us deal craftily with them”[2] etc. Under the influence of the zealous Jesuits who gained influence in this country at that time, in the year 1495 the Orthodox Bishop Alexander Jagiellonczyk expelled all the Jews from his district confiscated their property, which they had obtained through great toil. When Maytchet was established along with other villages in the 16th century, there were only a few remote villages without Jews[3].

However, very soon the rulers of the country realized that the advice of the Jesuits was wrong and that their country sank very quickly into economic chaos without the hard-working Jews. The economic benefits that came to them from the diligent labor of the Jews disappeared as if had never been there, and the property that was confiscated went to the greedy church. Only after their eyes opened up to see the light, did they turn from their wicked thoughts and, in April 1505, the Jews were allowed to return to their homes, and with that return the Jews also went to new areas of our district with the idea that they would build up those areas as well.

|

|

| General view of Mochadz |

[Page 33]

Here is the place to note specifically that after the cancellation of the expulsion decree, the pillaged property of the Jews was returned to them, but they never received the full rights back that they had before. Furthermore, they were burdened with a special tax, called the “Return Tax,” (powrotny), which henceforth was a customary tax that every Jew had to pay to the Lithuanian State, together with the head tax, for the benefit of the national coffers.

We also find in the ledger of the Council of the State of Lithuanian from the middle of the 17th century, more than150 years after the return of Jews to the area, the concept of the “Return Tax” from the area towns of Dvorets, Zhetl, Maytchet, etc., which by that time had obtained the status of independent communities that paid taxes to the Council of the State of Lithuania.

Another transfusion to the Jewish body of Lithuania occurred after the unification or Lithuania and Poland from 1516 and onward, when the two sister nations unified into one kingdom. A new element was added to the Lithuanian Jewish corpus, the source of which cannot be fully defined, and that was the Polish Jews who streamed into and integrated themselves into that area that had become a part of Poland. That integration went very well. The scholarly Lithuanian Jews, who were so sharp that they received the name of “the brain” of Jewry, absorbed the religious fervor from the Chassidic Polish Jews, who were known as the “heart” of the Jewry. They complemented each other. From this one can understand the existence of the Chassidic courts in the big cities and the small villages in the area.

Lithuania's Jews experienced hard times, which were a normal part of Jewish life in the Diaspora, and about which we will talk in the next chapters. As our sages have said, “Be mindful of the children of poor people because from them comes Torah learning.” Such it was with the Lithuanian Jews, including the area of Polish Lithuania, as they produced great names in all areas, with the entire Jewish people depending on their Torah and wisdom. Jewish natives of Lithuania became the pillars of the Zionist movement and the Hebrew culture in many of the countries of the Diaspora, such as South Africa, etc.

d. Area of Many RegimesWe cannot say how successful the post 1917 revolution regimes were in both abolishing the old world according to the revolutionary doctrine; and in building a new and better world. But when it comes to the Jews who had so much hope in the revolution and sacrificed so many people and much property-their world was literally darkened. Everything collapsed very quickly approaching World War II when Hitler, the firstborn of the Satan, may the name of the evil ones rot, destroyed almost all the Jews of Europe through his madness and cruelty. Few people survived this war of annihilation. Some of these survivors immigrated to Israel to build a new State and build up the country and build a new life for themselves.

The regime of Sodom and Gomorrah is only the end that testifies to the essence of other regimes that preceded it and greatly affected the character of the Jews in the Diaspora

[Page 34]

including our area. The Lithuanian Polish region, with Maytchet located at its center, was a battleground where Eastern and Western armies fought throughout the generations. It passed from one hand to another, but everyone had one deep-seated goal, to suppress the Jews, each in accordance to his way.

The era until the end of the 13th century, was known as the era of settlement of that area with all the occurrences of incursions and retreats from both sides without any permanent regime, accompanied by the temporary invasions and attacks of external elements such as the Tatars, Cossacks, Swedes, etc. Only beginning in 1291, with the establishment of the Lithuanian archdiocese, did the Lithuanian rule became more permanent, lasting for 278 years until the merger of Poland and Lithuania in 1569. Lithuanian rule began with a liberal spirit toward the Jews, who were invited to inhabit the country and participate in the formation and building of the country. However, the attitude of the regime changed very quickly, and the Jews were commanded to leave the country after they devoted their lives and blood to the building of the country. However, the rulers of Lithuania very quickly regretted what they had done and the Jews were allowed to return, but the rend in the heart never healed. The real goal of the government was revealed in particular when it needed the Jewish money and it imposed a special “Return Tax” in return for their right of return; and which remained in force as a Jewish tax which they had to pay throughout the entire period of their rule.

With the “Lublin Unification” treaty between Poland and Lithuania, they became one country in all respects and the Polish government continued for 226 years. The attitude of the Polish government to the Jews was not as it seemed. On one hand there was a tradition of the respected Jews who excelled in the development of the country, and that allowed the Jews to have religious autonomy which was granted to them under the rubric of the Council of the Four Lands. On the other hand, the Polish people were very deeply rooted in anti-Semitism, and the liberal Polish government turned the vast Jewish center into a virtual ghetto. Every Polish landowner wanted with all his heart to see the Jews disappear except for his own private Jew, who was forced to sing and dance before him saying “How beautiful you are.” These are the three typical symbols of the Polish Diaspora and its regime.

The third regime that left its mark upon the area in a very destructive way to the image of the Jew was the Russian regime, which established itself after the third partition and the complete destruction of Poland in 1795. It is proper to note that, whereas the preceding Polish regime was liberal to the Jews, albeit with a policy of degradation, the Russian regime acted with an iron fist and with a policy of oppression. Everywhere that the Russian regime reached, the Jews were limited in where they could live. The limitation was called Krumi Yevreyeb, which means everything is allowed to everyone except for the Jews. The civil rights of the Jews were gradually decreased until the Council was completely abolished. A law was enacted prohibiting Jews from living in villages, banning certain trades, etc. Pogroms also took place.

These were the three main regimes that lasted for several centuries and left their mark upon life in the area in general, and Jewish life in particular, throughout many generations. Nevertheless, we cannot ignore regimes

[Page 35]

that lasted for briefer periods, but whose influence lasted for a long time, such as the renewed Polish government that succeeded in quashing all the hopes and dreams of the Jews during its 19 years of existence. Of course, there was the Nazi regime that lasted for over three years, which was the most fatal and tragic to the local Jews who had already experienced so much pain and suffering, about which we will devote chapters later in this book.

e. The disturbances of Tach veTat (the Chmielnitzky uprising) and other such disturbancesIn the wake of the Cossack Rebellion led by the enemy Chemil, the rebellious farmers swept through western Ukraine and the area of Podolia and Volhynia, drowning the Jewish residents in rivers of blood, until their bloody march reached Pinsk. Some sources say that they even reached the swamps of Polesia and arrived at the cities of Slonim, Grodno, and even Minsk, but there is no official confirmation of such. Nathan Nota Hanover listed in his book Yaven-Metzula all the names of the communities that were destroyed. He does not mention Slonim, and the nearby communities such as Maytchet, Zhetl, or others. Aside from the echoes of the terrible atrocities that overtook the Jews of Poland and the help that was given to the refugees, we find no mention of the atrocities in the Ledger of the Council of the State of Lithuania, that continued its activities during the years of Tach and Tat (1648-1649) and beyond without any interruption, until the end of its existence. We find that the 12th meeting of the Council took place in the month of Shevat in 1649 in the small town of Mistkevich. At the 13th meeting took place 1650 in Zabludova, large sums of money had to be paid by the Jewish communities of Dvorets, Zhetl, and Maytchet, and others who had to pay debts that were created in the winter of 1648.

The Cossacks attacked the Polish nobility and Catholic churches wherever they went. However, these incidents were not recorded in any municipal or district courthouse records in Slonim. There is also insufficient information in the history books of the area communities to reveal the tragic events that happened to the Jews. It is known; however, that many communities paid higher taxes during those years, which is a sign of their economic success.

In contrast it is clear that in the year 5416 (1655) the Cossacks arrived in the district of Slonim, destroyed the Catholic Monastery in Zyrowa, and viciously attacked the towns and villages in the area. Even though we do not have detailed information about killings of Jews, we still know that their economic life was almost paralyzed. The urban Christian and the Polish nobility with the help of the Catholic priesthood led by the Jesuits, who were growing strong in Lithuania at that time, spared no disgusting effort to attack the Jews and afflict their life.

With the great confusion, the Jews of Ruzhany were accused of a blood libel in the year 5418 (1658). This ended with the execution of two of the leaders of the community. This unfortunate event laid the groundwork for other libels and for the danger of

[Page 36]

general expulsion of the Lithuanian Jews. Feelings of fear overtook the Jews in the region and their communities, which were obligated by the state council to pay heavy fees to intercede in the libels, and were weakened to a low level. It was not only the communities of the area, but also the large community of Slonim that had to take out high interest loans from the priests of Zyrowa. They were unable to repay even the interest, and became completely dependent upon them.

As if the load of troubles and tribulations of the Jews of the area was not full, from 1654 to 1655 the Russians and their Swedish partners that took part in the Thirty Year War of Poland attacked the Jews and killed many without mercy. The communities of Lithuania that miraculously survived the Cossacks during the tribulations of Tach VeTat, were now being murdered by the Russians and Swedes, and reached the point of poverty and desperation. Because of the terrible situation of the Jewish community, especially in the area of Novogrudok , the Council of the State of Lithuania could not deliver the correct head army to the state coffers. In 1712 a lawsuit was registered to the Supreme Court in Vilna for not paying the taxes of the sum of 25,000 gold coins.

The communities mentioned in the lawsuit included Slonim, Dvorets, Zhetl, Maytchet, Polonka, Stolovichi, Mysh Nova, and others. The verdict was a very harsh, and consisted of a death sentence for the community leaders if the money would not be paid within the time frame set in the verdict.

To sum up this difficult and bitter period that was the lot of the Lithuanian Jews, it must be stated that because of the continuous wars and poverty, there was a major plague spread through the area that killed many.

f. The region and its Spiritual InfluenceNo historical period that is measured as a whole entity. Rather, it is part of a chain of generations and periods. Each period is part of a chain of epochs, and is a result of the preceding one and a base for events of future generations. Similarly, a geographical specific point is a sum of influences from external factors from other geographical centers, primary and secondary, that influence its existence physically, spiritually and culturally. It is clear that this little town in Lithuania is, first of all, Lithuanian in its essence.

The area of the influence of Maytchet, of which it is the center, developed between the Neiman River in the northwest and the Pripet River in the southeast and the large cities surrounding it: Vilna in the north, Grodno and Bialystok in the west, Brisk and Pinsk in the south, Minsk in the east, and Slonim in the center

[Page 37]

of the area. Before we describe the immediate region, i.e. the cities and nearby villages that conducted day to day commercial relations with Maytchet, we will describe more distant centers that had a significant spiritual and cultural effect on the area in general and on the city of Maytchet in particular.

Vilna - It was an ancient and significant town with 235,000 people, with a Jewish population of 80,000 in 1941. It was formerly the capital of Lithuania, and then a district city in Poland, and finally the capital of Soviet Lithuania. It was a large center of European Jewry for Torah, Jewish wisdom, enlightenment, and arts. It was nicknamed the Jerusalem of Lithuania (Yerushalayim DeLita). Its educational and cultural institutions included: an ancient university, a science academy, a conservatorium, a rabbinical seminary, a teacher's seminary, secondary schools in Hebrew and Yiddish, an ORT Technion, a center for Yiddish culture called “Vilner Yiddish,” YIVO, “Vilner Troupe”, Bund, a printing press and newspapers. The printing press of the Romm widow and brothers published the Vilna edition of the Talmud. The periodicals included “Hakarmel”, “Hazman”, and “Haolam”. Important scholars who lived there included: The Vilna Gaon, Rabbi Yehudah Halevi Horowitz, Adam Ha Kohen, [his son] Mikha”l, Yehuda Leib Gordon, Shmuel Yoseph Fine and others.

Grodno (Horodno) -- an ancient town on the River Nieman with 50,000 inhabitants; 20,000 of whom were Jews. It was one of the main towns in the Bialystok area during the era of Polish rule, and it is part of Soviet Byelorussia. It had commerce in wood, wool, and tobacco processing.

It already had a Jewish community in the 14th century. On account of its importance and great influence in the area, it was established as one of the three districts of the Council of the State of Lithuania. In 1789 the first Jewish press in Lithuania was set up by Baruch Romm. It moved from there to Vilna and became famous as the “Romm Press,” and later, the “Widow and Brothers Romm.” Rabbi Mordechai Jaffe, the author of “Halevushim”, served in the rabbinate of that community.

Białystok -- It was a district city during the era of Polish rule with more then 100,000 inhabitants, half of whom were Jewish (1939). The primary occupation of the local residents was with the textile and leather factories, most of which were in Jewish hands. Famous people included Rabbi Shmuel Mohilever, Zamenhof, and others.

Brisk of Lita (Brest Litovsk) -- it was the main city in the Polesia district, on the Bug River with 50,000 inhabitants and a large Jewish community. It was an important crossroad on the Moscow-Warsaw railroad.

In the 17th century, Brisk first became known as an important center of Lithuanian Jewry. The Council of the State of Lithuania designated it as a major district, and it became a location for conventions. Famous rabbis of Brisk included: the Maharsha”l, Rabbi Yoel Sirkes the author of the Ba”ch, Rabbi Chaim Solveitchik and others.

[Page 38]

Brisk was destroyed in 1648 by Chmielnitski's soldiers, but the line between Brisk and Pinsk served as the northern border of their bloody rampage.

Pinsk - It was a city in the region of Polesia with the Pinsk marshes at its center. In 1939 there were 37,000 inhabitants, of whom 24,000 were Jews. Most of the industry and commerce, mainly dealing with exporting wood to Danzig, was in Jewish hands.

There was a Jewish community from the 16th century, which was one of the three first districts of the Council of State of Lithuania. It played an active role in the dispute between the Misnagdim and Chassidim. The Jews suffered terribly from the Cossack pogroms of Chmielnitzki.

Minsk - The capital of Soviet Byelorussia on the Svisloch River, southeast of Vilna and on the Moscow-Vilna-Warsaw railway line. In the district of Lithuania, it is the twin city to Vilna in its population and Jewish cultural importance. Before the Holocaust there were 60,000 Jews out of a population of 238,000 individuals. In the 14th century Minsk was annexed to Lithuania and in the 16th century it became part of Poland during the 1569 unification.

From the 16th century, Minsk had an important Jewish community under the rubric of the Council of the Four Lands, and later in the Council of the State of Lithuania. In its time, Minsk was known as an important Torah center, with the following rabbis: Rabbi Yechiel Halperin the author of “Seder Hadorot”, Rabbi Arieh Leib the author of “Shaagat Aryeh” and others. It was an important base of the Mitnagdim, had a great deal of Haskalah activities, and was an important Zionist center. It hosted the Russian Zionist council from 1902.

g. Immediate Surroundings and Economic RelationshipsAfter we have described the broader district from which Maytchet absorbed its spiritual and cultural influences, directly and indirectly; it is now appropriate to turn our attention to the immediate area with its cities and villages, which set up their roots from the time of their establishment, and to look into the settlements with which it had day-to-day contact and which served as its base for livelihood and sustenance. First of all…

Slonim - An ancient, historic city dating from the middle ages on the banks of the Szczara River. Before the Second World War there were 14,000 inhabitants.

It is a very well-pedigreed city, whose elder generation was a pleasant mix of rabbis and scholars who were great in Torah, and Jews of renown who had a sharp Lithuanian “mind,” and of Admorim and Hassidim who possessed a warm Jewish “heart'. The younger generation excelled in their sweet Jewish folksiness.

It was always a primary city and an example for other cities and towns whose residents came to Slonim to study in its Yeshivas, to spend time in the Hassidic courts, and to draw from its great spiritual treasuries in the realms of Haskalah, Zionism, revolution, etc.

[Page 39]

During the days of the autonomous Lithuanian Council, Maytchet and surrounding towns were affiliated with the large Slonim community.

Baranovichi - It was a relatively young city that was established after the construction of the Moscow-Brisk railroad in 1873. This place, which had formerly been a pine forest, became an important crossroads, and many inhabitants of the surrounding villages and even farther-away places were attracted to it.

Baranovichi developed mainly during the Polish regime, which established it as the district city instead of Slonim that served as such during the time of the earlier Russian regime. Administratively the councils of Mush, Maytchet, Polonka, Stolovich, and Horodishtch belonged to this community. Of the 28,000 inhabitants, less then half were Jewish. The diligent Jews were in control of most of the business and trades of the city, whereas the Christians were the government officials and the military people.

Baranovichi was the center for Torah and Hasidism. The two large Yeshivas attracted youths and young married men from the towns of the area. It also served as Jewish cultural center, with all its ramifications. Six weekly Jewish newspapers were published in Baranovichi, and the city exerted a strong influence on the towns of the area.

Stolovichi - It was a small town 7 parasangs[1] from Baranovichi, populated primarily by urban Christians (misczans) and a few hundred Jewish families. Stolovichi was situated on a main road, and served as a stopover from routes of many directions, for all routes led through Stolovichi. Its roads spread out in four directions, and were a stopover for horses and carriages.

Since it was an important crossroads, from early times Stolovichi had market days, which were known afar. The entire economy of the city, both of the Jews and the Christians, was based upon them. These market days indirectly affected the economy of other towns of the area, Maytchet included, for people would go there with their handiwork and various merchandise to sell.

Mush regarded itself as the mother town of Baranovichi. For a long time, people would call it New Mysh. It was an ancient city, as is shown by the old ledger that included historical facts. In the census of 1897, Mush had 2,995 people, including 1,764 Jews.

Mush is about four parasangs west of Baranovichi. In marriage documents and other certificates, Baranovichi is noted as “Baranovichi near Mush.” Before Baranovichi was founded, Mush was a city blessed by G-d, whose Jewish residents earned their livelihood in a plentiful manner. However, once Baranovichi was founded around 1884 and became a railway stop, many of the residents of Mush moved there,

[Page 40]

to the point where it became emptied of its residents and sources of livelihood. From that time, it was a wealthy man who had become impoverished, but who retained his family tree in his hand.

Zhetl[4] - It was a Jewish town on the road from Novogrudok to Slonim, about 12 kilometers from the Nowojelnia railway station. It had an old community with 3,000 Jews, who earned their livelihood throughout the generations in a meager fashion through their handiwork and by conducting small-scale commerce with the villages of the area. Despite being of modest means, the Jews of Zhetl were at a high level from a spiritual, cultural, and social perspective.

A large Yeshiva was established in Zhetl, in which Jews from all parts of Poland would come to study, and which was known for its geniuses. It also had Talmud study groups in which the scholars of the town and regular householders participated. It sent forth rabbis and scholars who of renown who were great in Torah. In the latter period, Zhetl was noted for its nationalist-Zionist activities and also as a center of the Jewish-Russian workers' movement.

Dvorets - It was situated close to Zhetl, and had a larger Jewish community than did Zhetl. The two communities shared a common lot throughout the generations, and appear for a long time as twin cities in the ledger of the Council of the State of Lithuania, that paid their tax quotas to the council in a joint fashion. However, with the passage of time, Zhetl developed to the point where it earned its status of an independent community, whereas Dvorets separated from Zhetl and was set up by the council as an affiliate of the community of Maytchet for that same purpose.

The Yeshivas of Volozhin and Mir - Without doubt, one of the wonderful traits, the fruit of the land with which Lithuanian Jewry was graced, was the voice of Torah that burst forth from the famous Yeshivas, which were the first and primary institutions in all the cities of Lithuania and the area. These included the Yeshivas of Slobodka, Radin, Ponovich, Novhorodok, and Slonim (in which the splendorous Maytchet Gaon Reb Hirsch served), Lida (in which the Maytchet genius KR”M served), Horodishets, and others.

However, we will discuss specifically the two large Yeshivas, which are Volozhin and Mir, which were like the Oxford and Cambridge of the Lithuanian region, whose good name spread throughout the Jewish Diaspora as centers of Torah and moralistic teaching (mussar), and whose sounds of Torah never stopped day and night. As is known, the Volozhin Yeshiva was founded by Rabbi Chaim the student of the GRA (Vilna Gaon) as a force of opposition against the Haskalah movement. Within it walls, there were Yeshiva heads, Gaonim and giants of Torah and fear of G-d; as well as 400 students who were diligent in their studies, including the national poet Ch. N. Bialik, the Maytchet Genius, and others.

The Mir Yeshiva, which was closer to Minsk, had more students that Volozhin; but the crown of the first born remained with Volozhin.

[Page 41]

|

|

| Maytchet youths in the Yeshivas of the area |

Villages of the area - It is appropriate to point out an interesting fact, which was not a particularly widespread vision throughout the Jewish Diaspora but was quite typical in that district - that many Jews worked in agriculture. Jewish residents lived in almost all of the villages around Maytchet. Some of them worked in leasing, trades and commerce as did village Jews everywhere, whereas another portion worked in agriculture in the fields and gardens. Both groups regarded themselves as belonging to the community of Maytchet in all respects. As is known, even the Maytchet Gaon was born in the nearby village of Sennichenenta to his father who was the lessee of the post office and inn of the village.

The following is the list of the nearby villages whose Jewish residents added a significant percentage to the Jewish population of Maytchet: Ivankoviche, Byalolozy, Dokorva, Zahorny, Zverovshchina, Khoroshovchitsy, 41Yatra, Mitskevichi, Medbedzini, Serebrishche, Svortova, Kalisheniki, and Rohotna.

It should be noted that the Jewish residents of the villages succeeded in escaping the sword of the Holocaust more so than the residents of the town.

Another source of information about the Jewish community in Maytchet can be found, without doubt, in the Yizkor books of the adjacent communities in the area, since they shared a common fate in terms of political and economic relations and also in the organization of the Jewish communities. It also should be noted, the problems concerning

[Page 42]

the general political matters and also the internal community life under the tyrannical government and the very difficult days including the poll tax levied on the Jews by the state, attempts to prevent blood libels and other vicious decrees, redemption of prisoners, aid to the families whose members were martyred, etc. The Jews of Lithuania suffered from another tax that was levied for the right to return to their former residence after the cancellation of deportations decrees.

All these matters were daily occurrences of the Jews of Lithuania and brought for discussion to the Committee of the State of Lithuania, where each community tried to give as much as possible to the fund of the Committee which was directly responsible to the government for the payments. According to the amounts of payments and their changing details we can learn about the conditions that rose and declined of the community.

|

|

| The early days of Maitshet |

And this is what we read in the “Shtetl Pinhas (Ledger)”, of the interesting work of Mordechai Vav. Bernshtein (Buenos Aires)

“In the meeting of the Committee from 1670, section 687, we read about the levy of “State amount”: three gold coins, 46 large ones and 100 large Polish ones). From this we learn for the first time, that also Maitshet was part of the partnership.” š Pinkas Zhetl (a/k/a Dyatlovo), edited by Baruch Kaplinski. Tel-Aviv, 1957.

[Page 43]

“In the meeting of the Committee in 1673, paragraph 706 we read: Dvorets (a/k/a Dzyatlava) with Maitshet eight large gold “foil““ to this Maitshet will give 6 “gdo'f.” From this budget we learn that Dvorets (which in the past was considered with Zhetl) became a partner with Maitshet, and we learn from this the portion of Maitshet in the general sum.”

And in the meeting of 1679 - Dvorets and Maitshet 26 large ones and in 1684 they gave 18 large ones until from 1601 Maitshet separated from Dvorets and appeared as a separate community with 7 large ones.

In the Pinkas of Slonim, a book by Kalman Lichtenshtein, in chapter 4, we read the following excerpts about the town of Maitshet and its surroundings from its beginnings:

“Despite the terrible isolation of the Jews among the hostile non-Jews, the Jews of Slonim succeeded during the years 1550 - 1648 to enlarge its borders and to continue to found small settlements in the area, the way they had done in the first half of the 16th century. Thus we note the existence of Jewish settlements during this time such as Zhetl, Roviny, Dvorets, Maitshet, Polanka (a/k/a Stolevitch), Drohichin (a/k/a Drahichyn), Halynka (a/k/a Golynka), Kossovo, Byten, - small communities that were without a doubt founded by settlers from Slonim, who arrived there after the establishment and strengthening their central community.”

In Chapter 6, of the above mentioned book, we read about the place of Maitshet among the family of Jewish communities in the area.

“Immediately upon the start of the Pinkas of the State of Lithuania, in the Committee of 1623, divided the state into three main regions: Brisk, Harodna, and Pinsk. Slonim was mentioned as belonging to the region of Brisk. In this section also are mentioned the communities of Roviny and Dvorets due to their growth in the beginning of the 17th century. From this we learn that many settlements in the area that had lesser Jewish populations than these two; and the fact of their existence was mentioned due to governmental and local acts - Slonimian, and they are: Ozernitsa, Kossovo, Drohichin, Zhetl, Byten, Seltz (a/k/a Syalyets) Polanka, Maitshet and a number of communities in the surrounding villages were directly subordinate to the community of Slonim.”

In addition direct and indirect mention was made in the memorial books of other communities in the area, that indicate the beginning of the establishment of Maitshet and the difficulties encountered in its development.

i. The Jewish town in the view of the newspapers

How wretched and pitiful looked the lives of the Jews in the big cities, and especially in the small Jewish towns, in the view of the newspapers of those days.

[Page 44]

Whether in the Eastern part, the “valley of tears” as described by the author Mendele that is reflected in The Melitz by Tzederbaum in Peterburg and that of the Western side, in Yavan Hametzula by Hanover, reflected in the Tzfira by Slonimski in Warsaw, the area of Lithuania was a middle ground reflecting parts of both sides; two are better than one.

And we should know, that in those days the idea of Zionism had not yet evolved and there didn't appear among the Jewish communities any other solutions to resist the decrees as was done in the democratic countries. In addition, the older generation was still deep in its old ways, the swamp of exile, and were able to bequeath to their children only tarbe that has no end and all the long-standing Jewish way of life. Therefore even new generations physically strong but weak in spirit, plodded along in the same stagnant swamp.

|

|

| The first houses in Maitshet |

If life was so wretched and downtrodden and the writers whose opinions were so empty and superficial, as if there is nothing more in their world but only cursed poverty and meagerness, the community-shtibl, the disputes and rumors. And if the sky was so dark without any horizons, vision and hope ceased to exist in the closed heart without realizing the wretched situation. And if the town stood still for many years and no one arose to write in the newspaper anything more than a fire in the streets, or a murder or theft or until a bishop would arrive

[Page 45]

for a visit and a delegation of Jews with Torah scrolls went to greet him and other such “news.” Therefore, it's not surprising that the image of the Jewish town in the view of the press was desperate and somewhat unpleasant, since that was the image and the character in sad reality.

Here are a few excerpts from the reports of the correspondents of the towns and area around Maitshet, that “constantly ran news reports that would be published on the front pages for all to see” in the periodicals.

HaMalitz - a notice to tell Yaakov everything etc. that happened in Peterburg the capital, written by Alexander Halevi Tzederboim.

Hatzefira - a periodical that reported news among the people of Yeshurun (Jews), published in Warsaw by Haim Zelig Slonimski.

MN- - - notifies: The number of Jews counted in our town is 280 families. There is one great synagogue that is standing since the year 5408 (1648), and another 6 Batei midrashim - Study Halls. Six organizations 1- Hevra Kadisha (for burials), 2- Bikur Holim (taking care of the sick), 3- Linat Zedek (hostel for the poor), 4- Hevrat Sha'ss (learning the Talmud) , 5- Hevrat Mishnayot (learning the Mishna), 6- Hevrat Tehillim (learning/reading the Psalms).

Rabbis 2, Rabbinical judges 2, shohet (ritual kosher slaughter) 3, cantors 2, beadles 8, teachers 13, writers of Torah scrolls, etc. 6, mikve caretakers 2, gravediggers 2, storekeepers 36, sellers of old clothes 6, horse traders 9, fruit salesmen 5, agents and intermediaries 7, bakers of bread and honey cakes 9, tailors and seamstresses 23, leather workers 21, waggoners 11, watch repairers 3, engravers 3, meat pullers 7, wood choppers and water carriers 7, chimney sweepers 2, manual laborers 9, musicians 4, makers of hand boxes 2, doctor 1, pharmacist, midwives 3, without any specific occupation 67, beggars 9.

These are the Jews who live in our town as counted.

Z --- (Grodno area). - On Monday night during the 10 days of repentance, a fire erupted and destroyed more than 100 houses and 3 Study Halls, also stores with their merchandise were burnt. The people of the city stand outside with their wives and children without a place to sleep. Therefore I ask of you in the name of the injured to quickly give them help whether in money or clothes and to send to ---.

MB ---We are told that on Shabbat Parshat Shmot there was a disturbance and confusion in the study hall during the prayers, between the leader of the prayers and the shohet - - - and there was such a great tumult that the neighboring Christians came to see what all the noise was about and they laughed that such foolishness about the leader of the prayers would cause the Jews to desecrate the House of the Lord.

H.P. - MM writes that from a nearby village three farmers came to a tavern run by a Jewish woman who poured them a drink, which they drank and became intoxicated. When she asked for payment they spilled

[Page 46]

out the liquor from the barrels onto the ground and they beat her badly almost to death. If only the police had arrived…

MM. We are told that on Friday, before last Shabbat the prayer hall of the Hasidim became like a battlefield. They beat each other, threw dirt, insulted and cursed each other like fishwives at the market. About 60 pieces of glass were broken from the windows and even the wives of the Hasidim took part in the “holy” war. And the men even grabbed the head coverings off the women in front of all. Finally, they filed their complaints and petitions to the magistrate and the mayor of the city to our disgrace and shame.

M.A. writes MM. - Our town looks like a hut in the field, all the workers have stopped working and live from the air. Due to zero work they walk around the town all day and spend their time in idle talk. Formerly many urgently went to work in the “golden” countries, America and Africa, but even a change of place didn't improve their economic situation because those wandering from place to place didn't earn much. Only infrequently were they able to send money home to their families who were left penniless, and others had to return bitterly disappointed.

The education of the children was sluggish and poorly done. The people found no use for education and no one sought it. I am not exaggerating when I say that there was almost no one in the whole town who had any knowledge of our literature or any idea of our nationalism. No one here even read the newspapers because it didn't interest them in the least.

MB. writes. - Due to the lack of a Talmud-Torah (elementary school) the teachers sit in special rooms and each receives his salary of three to five rubles a week. Each must go around to the homes every Friday to receive this pittance. This money is insufficient to maintain the Talmud-Torah and the community stands apart and awaits the coming of the Messiah.

Recently the home of the local Rabbi was burned. Among his possessions that were destroyed were the documents of his birth and marriage. The rabbi attempted to acquire permission from the governor of the province, that the district council provide a copy of the documents that are kept in their offices. However, many fees are required, which he did not have; he asked the local council to help but they claimed they couldn't aid him since they had no money. Thus those requesting documents were sorely disappointed.

[Page 47]

j. Summary Table Part One

| Until the end of the 6th century | Prehistoric period/movement of primitive tribes, Slavs, Lithuanians, Teutonians |

| 7th - 8th centuries | Beginning of small principalities, Slavic, in the East and Lithuanian in the West 200 yrs |

| 9th - 10th centuries | Overthrow of Lithuanian princes and fortification of Slavic princes in the area 200 yrs |

| 11th - 12th centuries | Constant clashes between Russians and Lithuanians and alternating control of each 200 yrs |

| 1241 | Invasion of the Tatars of Battu-Hen and their withdrawal in the same year 1 yr |

| 1291 - 1569 | Expulsion of the Russian princes to the East/Founding of the Lithuanian Archduchery/Consecutive Lithuanian government in the area for 278 yrs |

| 1316 - 1341 | The Lithuanian Prince Gadmin invites the Jews from various regions to settle in his land 25 yrs |

| 1386 - 1430 | Vitold the grandson of Gadmin grants special rights to the Jewish settlers who will develop his country 44 yrs |

| 1495 - 1505 | Jewish Deportation decree from Lithuanian by Alexander Yagilontzik/ in 1503 repeal of the decree and return of the Jews 8 yrs |

| 1503 | The approximate dare of the founding of the village of Maitshet |

[Page 48]

| 1569 - 1795 | Lublin Unified Covenant between Lithuania and Poland, autonomous Lithuania in the area and conseccutive Polish government for a period of 226 yrs |

| 1623 - 1761 | Rule of autonomous Committee of Jews of Lithuania 138 yrs |

| 1655 - 1659 | Russian invasion and war of the Swedes 5 yrs |

| 1670 | The Maitshet community is mentioned for the first time in the Pinkas (ledger) of Lithuania together with Dvorets and Zhetl |

| 1795 - 1915 | Final division of Poland and annexation of the area to Russia/Czarist Russian government for 120 yrs |

| 1915 - 1919 | German conquest in World War I 3 ½ yrs |

| 1920 - 1939 | After the interim Soviet rule - renewed Polish rule for 19 yrs |

| 1939 - 1941 | Soviet occupation according to the Ribbentrop - Molotov Agreement 2 yrs |

| 1941 - 1944 | Nazi occupation/annihilation of the Jews 3 yrs |

| 1944 | Annexation of the area to Soviet Byelorussia |

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Molchad, Belarus

Molchad, Belarus

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 14 Nov 2014 by LA