|

|

|

[Page 768]

by Y. Shmulewicz of New York

Translated by Jerrold Landau

Approximately 18,000 Jews lived in Mezritsh before the Nazi murderers began sowing destruction and devastation amid Jewish life in Poland. And what is the situation now in Mezritsh, the city of Jewish brush makers? If there are Jews there, where are they? How do the streets, the houses and the institutions, where generations of Jews lived and created, now look?

A short time ago, a Mezritsh Jew came to New York. Before leaving Poland, he visited his hometown, and saw Mezritsh for the last time.

The 48–year–old Nachum Gutman is a son of “Berl the Deaf.” That is what they called his father, who was also a brush maker. His mother was Rivka. Before the war, the family lived on 3 Szkolna Street, near the synagogue. Gutman's father, mother, two younger brothers Fajwel and Moshe, and two younger sisters Mindel and Rajzel were murdered by the Nazis.

Nachum Gutman recounts –In 1946, after I returned from Russia, where I had roamed during the wartime, I lived in Szczecin, Lower Silesia. I wanted to travel to my former hometown of Mezritsh many times. I wanted to see what had become of Jewish Mezritsh, what the Jewish city was like now. However, my heart did not permit me to do so. I couldn't…

Now, after obtaining my American visa, and soon to leave Poland on my way to New York, I decided to travel and see the former Jewish Mezritsh, so that I might remember it until I die.

He [Gutman] relates – While traveling on the train from Warsaw to Mezritsh, I was the only Jew. This was uncanny, how could one comprehend this? At one time, this same train was full of Jews, Jews from Warsaw, Jews from Mezritsh.

He [Gutman] continues–I arrived in Mezritsh. I saw the same station, as it once was, as if nothing had taken place. As I got off the train, Poles carrying sacks and baskets in their hands got off with me. I looked, floating in another

[Page 769]

world. In those moments it seemed that I saw a crowd of Jews: look, there go Mezritsh Jews!

Then Nachum Gutman crossed the small bridge; he knew the way very well from some time ago. Suddenly, his legs weakened beneath him. It seemed to him that he was walking on Jewish blood.

He arrived at the large Mezritsh market. Things began to perplex his mind. He did not recognize his hometown.

At one time, the market had been full of Jewish stores and booths. Also, the large hall, the “Rod,” had been full of Jewish businesses. Products of Jewish toil were placed on display and sold. Now the market had been turned into a large park, with vegetables and flowers. Poles were sitting there on the benches chatting amiably. A large loudspeaker was hanging from the town hall, playing joyous music, among other things. It appeared as if nothing had happened there. Yet there in the market, the Nazis had gathered the Jews together, beaten them, killed some, and drove the rest to their deaths in Treblinka. Thousands of Jewish men, women, old people and young people were shot in the market. Everything there was soaked with Jewish blood and tears. Now, flowers grow there, and they play joyous music…

Gutman explained that he had not eaten anything on the first day of his visit to Mezritsh. When he went to Szkolna Street #3, where he and his family had lived before the war, there was no trace of [the dwelling]. Everything had been eradicated.

There were only four Jews [remaining] in all of Mezritsh. One was the shoemaker Moshe Sroliwka, who lived in Reichman's home on Lubelski Street. The second was “Lajzer with the mustache,” an elderly Jew who hid with Christians during the war. Now as well, he lived among the Christians. There is still an elderly Jewish couple, the only Jewish couple in Mezritsh. He, Meir Mandelblatt (“Meir Morde”) had been a shoemaker before the war. His wife is Gittel, Itche Libe's daughter.

Nachum Gutman spent the few nights in Mezritsh with that elderly couple. The couple lived in a house that had once belonged to Yankel Szenker. The dentist Leon Bochenek had once lived in that house. As he said –he slept there! He left the house at daybreak. He went to Szmulowizna, where the Jewish Ghetto had been. Aside from the 18,000 Jews of Mezritsh

[Page 770]

whom the Nazis had driven into that ghetto, Jews from the surrounding towns of Radzyn, Biała, Lukow, Parczew, Nasielsk, and others [were also sent there]. Altogether, there had been 40,000 Jews in the ghetto. The hunger, sickness and crowding were unbearable. Now, there was a great wasteland, an emptiness, a vacant area there.

From there, from that empty place, once could see the Krzna River. The same well with two large wheels was there. Christians were carrying pails of water, as in the past. Nothing had changed… Once a week, on Thursday, the empty place on Szmulowizna had come to life. That was when the fair took place. Peasants came, and they bought and sold.

There was no trace left of the large, fine synagogue on Szkolna Street. It was the same situation with the large Beis Midrash and with the other Basei Midrash. On the other hand, the large Jewish hospital (without Jews now) on Warszawer Street, the hospital that the Mezritsh natives in America had helped to build before the war, had been used by the Hitlerists for their purposes. Now that fine hospital was being used by the Poles.

The firefighters' building, built by Jews, as well as the movie theater that Hirsch–Leib Cytryn built in the old city, were also still standing. There were very few new buildings in Mezritsh. Everything was from the bygone time, from Jewish toil, now used by others.

The “Beder” a wealthy Jewish lumber dealer, had once built a large house on the water. It looked like those in Venice. They used to say in Mezritsh at that time that the foundation alone cost more than three regular houses. Now, Poles were living there.

Yechezkel Sztajn's large house is now an infirmary. The militia now occupies Yosel Tisz's house. A Christian brush–making cooperative is found now in the former H. D. Nomberg Jewish Folkschule. They took over the former Jewish specialty.

Nachum Gutman explained that in the old Jewish cemetery, which the Jews no longer used before the war, but where generations of deceased Jews of Mezritsh were laid to rest, the Poles had built houses and were going about their lives. At the new Jewish cemetery on the Bialer highway, the Nazis had uprooted the monuments, and used them to pave the roads.

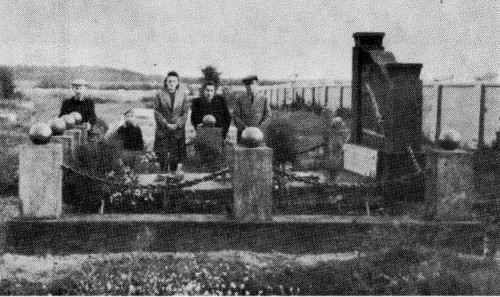

After the war, Mezritsh Jews who returned from their exile in Russia, as well as the few who had survived the Nazis, came back, collected the gravestones from various places and made a wall around the cemetery. Near the large mass graves, where

[Page 771]

the remains of thousands of Jews who were shot now repose, a large monument was erected. This was done with the help of the Mezritshers Avraham and Sarah Finkelstein of New York, and with the help of the American united Mezritsh Relief Committee.

On August 25 every year, the aforementioned elderly couple, Meir and Gittel Mandelblatt, go to the monument in the cemetery and light six candles there. That date is the anniversary of the large Aktion that was perpetrated against the Jews of Mezritsh.

|

|

| The mass grave in the Mezritsh Jewish Cemetery |

[Page 772]

Buildings remaining intact that were not destroyed

|

|

| Sapir's mill |

|

|

| Built in 1938, on the eve of the Second World War |

[Page 773]

|

|

| Brik Gasse –Bridge Street |

|

|

| Warszawer Gasse. The first house belonged to Yossel Tisz. The rest are new houses. |

[Page 774]

Mezritsh survivors in their wanderings

|

|

| Mezritsh brush–cooperative in Reichbach [1] (Lower Silesia) in 1947 In the second row, seated, from right to left: Yitzchak Wysznia, Shepsl Ekerman, Alter Skwarne, and others |

|

|

| Mezritsh families with children in Szczecin |

Translator's Footnote:

by Nachum Gutman of New York

Translated by Jerrold Landau

Impressions from a visit to our hometown

In 1946, I returned to Poland from Russia, but instead of going to Mezritsh, I went to Szczecin. I remained there for 16 years. I never traveled to visit Mezritsh during that entire time. Why? I knew that I had nothing to look for there. I received information in Szczecin that Mezritsh with its 18,000 Jewish souls is no more. They were murdered at the hands of the Nazis and their collaborators. The small number of survivors had left Mezritsh.

Nevertheless, my heart was connected to Mezritsh, to the place where my cradle had once stood. Among the greetings that I received from Mezritsh, one brought a bit of comfort: I heard about the great deed that Reb Avraham Finkelstein and his wife Sarah [of New York] had performed for the murdered Jews, who had met their horrible deaths in the cemetery, including Rabbi Raszka of Mezritsh; and also for the Mezritshers murdered in the vicinity of Mezritsh. They had all been brought to a Jewish burial in the Mezritsher cemetery. Thanks to the Finkelsteins, the cemetery has been renovated, a funeral chapel has been erected, and the cemetery has been enclosed with a new wall. Incidentally, thanks to a large sum of money that the Finkelsteins donated for that purpose, the grave monuments that were used [by the Nazis] to pave the Mezritsh sidewalks and were recovered and used to make the new wall, thereby leaving at least a memory of those murdered – some sign that Jews had once lived in Mezritsh.

On the eve of our journey to America, I decided to visit Mezritsh. I visited the town several times. I hoped to find a Jewish memory to which the Finkelsteins had so greatly contributed. I found the cemetery abandoned, however, and in a terrible state. I knew that if the situation was not quickly rectified, it would only be a short time until no one would know that Jews had once lived in Mezritsh. Meir and Gittel Mandelblatt lived in Mezritsh at that time. Meir later died, and his wife, may she live long, lives today in Israel. I approached Meir Mandelblatt, peace be upon him, and requested that he help me find

[Page 776]

|

|

| The wall that was assembled from the collected monuments in the Mezritsh cemetery |

|

|

| The front of the monument at the communal grave |

[Page 777]

an honorable gentile who would maintain the cemetery and serve as its guardian. He suggested that I speak to the former postman, and ask him to take responsibility for maintaining the cemetery and serve as its guardian, of course for a salary. I spoke to him and realized that he was a respectable man. I proposed that he accept the position. I promised that [once] in America, I would arrange for a regular salary for his efforts, and in the interim, I gave him a deposit of a sum of money. He brought the cemetery back to a good state.

When I arrived in America, I initiated a campaign in the Mezritsher Society, asking that they allocate an annual pension for the guard. I clarified the importance of this, and the pension was allocated.

When I was already in New York, I received news from Mezritsh that a local priest wanted to take over the cemetery and turn it into a czmentarz [1]. He proposed to leave only the area with Jewish graves as a Jewish cemetery. I began a campaign to not permit this. I wrote letters to the Wojewoda [2] in Lublin, to Warsaw, and the Polish embassy, demonstrating that the cemetery was the property of the Jewish community and could be used only as a Jewish cemetery. The intervention was successful. The priest retracted his plan.

The guard maintains his watch, and I hear from him from time to time. If anyone goes to Mezritsh, they will find the cemetery as the sole testimony to the existence of Jews in Mezritsh.

Translator's Footnotes:

by Avraham Blusztajn

Translated by Jerrold Landau

The First Victim

Chaim was the second son of Shaya Berezowski (Bolnik), after Mottel and before Yankel. In 1919, during the Polish–Bolshevik War, he was mobilized [to serve] in the Polish Army and immediately sent to the front. The Jews in Poland were “satiated” with wars, and so they did not demonstrate any great sympathy for the war.

To this day, the tears that the handsome, sturdy young man shed as we parted are etched in my mind. He had a premonition that he would not return alive.

The sad news of his death arrived not long thereafter. A bullet from a Red Army soldier killed him.

The Second Victim

Yankel was an active participant in the Communist Movement, first in the youth circles and later in the party. He belonged to a group of dedicated idealists. The terror and constant persecution by the Polish government organs were unbearable, and [Yankel's group] felt that the ground was already burning under their feet. They decided to sneak across the Soviet border. They indeed succeeded in arriving in Russia in 1932 with the help of a paid border smuggler.

The meager news that arrived from the hermetically sealed Russia played with the fantasies of many such youth. After a year, the relatives received the first letter from Magnitogorsk [1]. Nobody thought that they would be simply sent to the Urals, far from central Russia. From that group, David Wyszkowski and Shprintza Lederman miraculously survived. They informed us of what Yankel had endured during the fifth year, until 1937, when he was shot as a counterrevolutionary and spy.

[Page 779]

The Third Victim

Mottel Ajzensztajn (he was called by his mother's maiden name) was one of the pillars of the Bund in Mezritsh. He was the chairman of the professional brush–makers union for many years and was well–known in the headquarters of the professional movement. He was a factory worker for all those years, and never aspired to become a paid functionary. He lived with his family (a wife and two children) in great straits. His appearances at the gatherings and meetings were always matter–of–fact, and he obtained much experience in the frequent negotiations with the [town's] employers. He was in constant conflict with the Communist activists. Nevertheless, they respected him for his honesty and sincerity.

A typhus epidemic broke out in 1916, a year after Mezritsh was occupied by the German–Austrian Army. Binyamin Feldman, a close friend of Mottel, was taken to a field hospital and placed in isolation, and it was strictly forbidden to visit the sick. Mottel took the risk, however, and brought him fruit. This was noticed by the soldier on guard. Mottel escaped but fell down. The soldier did not have any loaded weapons, so he stabbed him with his bayonet. Mottel struggled with death for a long time but eventually overcame his wounds.

Before he regained his strength, he was sent, along with a group of youth, to forced labor in Courland [2]. Only a small number returned from there alive. Many died from the difficult work conditions and meager nourishment.

At the end of the [First] World War, Mottel returned to Mezritsh broken. Before he regained his strength, the Polish–Bolshevik war broke out. The Bolsheviks were in Mezritsh for eight days on their march toward the Wisła. When their front was broken and they were retreating, Mottel was among the thousands of youths who left the city together with them. The Polish Army, pursuing the Bolsheviks, reached the fleeing youths. Mottel fell into the hands of such a group of wild soldiers. He was given over to the “fine”, sadistic torturers. Mottel endured everything. Fate had it that he, the last of the three brothers, would also be killed by the Communist authorities.

[Page 780]

In 1939, when fascist Germany attacked Poland after the infamous Ribbentrop–Molotov pact, Mottel went over the Russian side along with his young daughter and many others. None of us could imagine that the Russian regime would act with such brutality toward the refugees.

Mottel began to work in his trade. Incidentally, he was a good tradesman. Throughout all the years, he strove to live in a Socialist society. He wanted to work honestly and live out his years. He never discussed this with anyone or expressed his intentions.

About one month later, the writer of these lines also visited Homel [USSR], and began to work in the same factory [as Mottel]. In Homel, we were hosted by a common uncle, who took us in temporarily. After I had already been in Homel for a month, [Mottel] took me for a walk to get to know the city, especially the places where one could get something to eat. He took me to a bazar and a bread enterprise. This was in December. Old people, covered in rags and barefoot, lay on the steps of the enterprise, begging from everyone who exited the business, “Peterl, give a morsel.” Mottel understood what this meant for me.

After a few months, when we had already become accustomed and had made peace with the situation, Mottel was arrested by the N.K.V.D. Faithful to their ways, they ransacked and searched for victims. They summoned everyone for an investigation. As it turned out, some Mezritsher, perhaps a Communist who wanted to ingratiate himself, reported that Mottel was a Bund activist. They arrested him and accused him of coming to the Soviet Union in order to overthrow the Soviet regime.

I talked to him a few days after his arrest. Srulke Kawe, his party comrade, had already been detained. I made Mottel understand that his fate would certainly be the same. He still had the possibility to return to Brisk [3], as others had done. His answer was categorically negative. He declared to me that he had raised his hands and accepted his fate.

He was killed a short time later.

Editor's Footnotes:

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Miedzyrzec Podlaski, Poland

Miedzyrzec Podlaski, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 16 Jan 2023 by JH