|

|

|

[Page 62]

Dov Rabin

Translated by Eszter Andor

General Overview

On the eve of the 20th century, in the census of 1897, 3,542 Jewish souls were counted in Krynki. They made up 71.45% of the 4,957 inhabitants of the whole shtetl. According to the Polish Dictionary of Geography of 1883, 20 years earlier Krynki had had 3,336 inhabitants, and 2,823, that is, 84.62%, of them were Jewish. Since 1847 a total of 1,686 Jews came to the shtetl, and of them about 719 settled in the last two decades of the 19th century. This means that in 40 years the Krynki Jewish colony doubled. However, after 1897 the Jewish population almost stopped growing, apart from the natural increase and the influx of Jews who came to Krynki from the surrounding settlements in search of a better living in the shtetl which had been economically prospering for a number of years, and the percentage of Jews in the general population of the town even diminished a little.

The growth of the Jewish population in Krynki came to a standstill because many inhabitants left the shtetl and emigrated. Individuals, enterprising young Jews left the town for America already in the 19th century. The repression of the czarist police, however, which started to pour down on the awakened tannery workers and revolutionary youth of Krynki following their frequent strikes, forced the Jewish 'lads' (young, daring members of revolutionary circles)—especially after 1902—to leave their homes and escape--emigrate by the hundreds abroad, mainly to North America. As time passed this emigration intensified and later, when the first wave of immigrants settled down and became more or less 'Americanized' in their new haven, they started sending 'ship tickets' home to their families and friends, especially when the Krynki leather industry started experiencing a serious crisis which became even more acute after the First World War. In due course Krynki Jewish 'colonies' appeared in many countries and grew in size until the number of compatriots in these 'colonies' equaled those in Krynki itself.

A regular part of the more than six million Russian Jews, the Krynki community also experienced the fate of the Jewish communities in the period under discussion especially in the social-political and spiritual-cultural domain. Krynki Jews endured the same vexations and restrictions introduced by the Russian government as the whole Jewish population of Russia. At the same time, however, they found enough opportunities to derive great satisfaction from various domains of internal Jewish life, and from the Jewish tradition especially, with which even the anti-Semitic despotism of the Romanovs did not dare to interfere. As can be expected, the Krynki chronicles—press reports and descriptions—and even the memoirs of the compatriots usually concentrate on the local events, especially on those that could be of general interest and even on things of global significance, that is on the incidents related to the Jewish labor movement,

[Page 63]

as for example, the 1905 revolt of the tannery workers in Krynki or their epic strike.

Witnesses gave long lists of Krynki heads of the families who at the time of the Kishinev massacre in 1903, which shocked all Jews, especially the Jews of Russia, and of Krynki, hastened to give donations speedily for the victims of the pogrom. These lists, which appeared in the Warsaw paper Hatsefira in June 1903 (see p. 226), contain the names of rich middle-class manufacturers and their journeymen tanners, as well as of other strata of Krynki Jews.

The most important, and sensational, political event – with the tannery workers and revolutionary youth as its heroes – which affected the Krynki Jewish community was the rebellion against the czarist government in January 1905, during which the freedom fighter 'sisters and brothers' expelled the local lord and seized power in the shtetl for a few days. We shall describe this in detail later on.

The young Jewish revolutionaries of Krynki who belonged to political trends, which adopted terrorist methods in their struggle, became famous even far from their hometown for their daring acts and self-sacrifice. Sikorski, a Krynki Jewish tanner, member of the social revolutionary movement (SR) participated in the attempt on Viacheslav Pleve, the cruel czarist minister of interior, who was responsible for the Kishinev pogrom. With dynamite bombs in hand, Sikorksi and his two accomplices (Igor Sazonov and Sergei Kalaiev) waited for Pleve at the Warsaw station in Petersburg on June 15, 1904. Kalaiev threw his bomb first and killed the evil antisemite. Sikorski was sent to Siberia and he never came back.

The seventeen-year-old anarchist Niomke Friedman finished his very active life with an attempt on the cruel commander of the Grodno prison in revenge for his whipping and bullying the young Jewish female strikers of the tobacco factory who had been arrested.

Yisroel Galili, leader of the Haganah and minister in the Israeli government, recalls (in his book entitled Eliyahu Golomb – Chevion 'Oz, vol. 2, Tel Aviv, 5796) Niomke's name when describing the reminiscences he heard from the deceased Eliyahu Golomb, chief commander of the Haganah, as well as from the leaders of the Histadrut and from members of the Jewish colony in Palestine in general. In his recollections of his young years in Krynki (he himself was born in Volkovisk) Golomb portrays his 'comrade' Niomke as a “Jewish hero who risked his life to take revenge for the torture of Jewish women strikers”.

No less important and also of general interest, especially for the history of the living conditions of the Jewish workers – a long affair about which there was much commotion in Russia – were the series of bold and heavy strikes organized by the Jewish tannery workers of Krynki for humane working conditions. Much has been written on these strikes and we shall also discuss them in detail in the present study.

The tanneries – leather manufacturing – became the backbone of the economic life of Krynki already in the 1890s. Of course, even then many Krynki Jews made a living out of traditional petty commerce and crafts, and awaited the weekly market day when the peasants of the nearby villages came to town to sell their products, their poultry and

[Page 64]

cattle, and to buy and order what they needed, and to have a drink or fill themselves with beer or kvass and stuff themselves in the eating-houses on the market.

Whether Thursday influenced the lives of the little shopkeeper on the market and of the plain traders, of the Jewish blacksmiths, cart-wrights, harness makers, cap makers, bakers, barbers, and the like is hard to say but it is certain that the leather factories and the masses of tannery workers were the main life force of the shtetl and of the artisans and merchants. The shopkeepers, tailors, shoemakers, quilters, bakers, butchers, coachmen, locksmiths, carpenters, masons, flour dealers, glaziers, and so on, all lived off the manufacturers and their workers. A strike in the tannery or a crisis in the leather industry steeped the whole town in crisis.

As early as 1896 there were already 20 factories which tanned horse skin and employed hundreds of workers, among them also a small number of Gentiles. The tanneries yielded large profits and the manufacturers were getting richer and richer. There was no lack of Jewish initiative in Krynki, the number of leather factories grew, the volume of production was on the increase and the number of employees multiplied. Skin was brought from as far as Siberia and the Caucasian mountains, as well as from abroad, from Germany, Austria, France, and even North and South America. The spacious realm of the vast Russian Empire and even foreign countries served as a market for the leather industry. In 1897 there were already 500 to 700 tannery workers in Krynki, their numbers grew to eight hundred in 1898, a thousand in 1901, and then to 1,100 (from which 160 were Gentiles) in the sixty-seven tanneries of the shtetl. The leather manufacturers were considered the richest people in the Northwestern region of Russia as early as the 1890s. Thanks to the Russian-Japanese war of 1904 the already booming leather industry began to flourish even more. Russian soldiers, and not only the military, needed boots. There rose a great demand for leather and the tanneries continued to grow for some years.

In the heyday of leather manufacturing when the manufacturers had already become rich and their master craftsmen well-to-do bourgeois, the tannery workers lay in the abyss. They worked 15 hours a day, and even more on Thursdays and before holidays, and sometimes they had to work even on Saturday night. The wages of the 'dry tannery' workers were negligible and they were paid irregularly and haphazardly. In the 'dry tanneries' the manufacturers would make their life easier and at the same time increase their profit by handing out the piecework (the work on a piece or part of skin) to master craftsmen as 'contractors' (subcontractors). These in turn would hire journeymen and underage apprentices for a 'term' (half a year from Pesach to Succoth) on a weekly pay and exploit them in the most extraordinary ways.

The master craftsman would pay only a wretched wage of few rubles and pay it when it was advantageous for him: usually after the 'term' was over. During the 'term' the workers were forced to appeal to the mercy of their boss, the master craftsman, to get a few rubles for the doctor, in case of the birth of a child, a wedding, or, God forbid!, some misfortune. The whole life of the workers was about trying to make ends meet by borrowing and buying from the shopkeeper and the baker on credit, and by asking the artisan to make or mend shoes or clothes on credit. They would send their order and pay the bill when they could. And to make matters worse, it would often happen that the master craftsmen

[Page 65]

did not pay even that wretched little wage earned by hard work, declaring themselves bankrupt or simply disappearing from the shtetl with the money.

Punishment was a widespread custom if a tool was damaged or broken or a little cod liver oil spilt. If a worker talked back to the master craftsman or protested, the 'impudent man' was sent home and got a good beating too, and his creditors were informed that he had been sacked and he was no longer credit-worthy. Such a man would not be hired in any other tannery without a note from his previous boss.

The working conditions were dreadful in terms of hygiene and sanitation: stuffy air and foul smells, cold, and constant humidity characterized the 'wet tanneries', and great heat in the drying rooms the 'dry tanneries'. Consumption and rheumatism were frequent diseases among tannery workers and 'wet tannery' workers often suffered from the fatal Siberian plagues (a contagious type of ulcers which the workers caught when touching sick animals with wounded hands). At that time the health or life of the workers, let alone their toil, were forlorn. There existed no workers' organization in Krynki yet and the workers had no class consciousness and did not think of getting organized. People knew nothing of social legislation. No one complied with the few existing government decrees on ensuring hygiene in the factories and workshops and there was no one to enforce these decrees.

Part of the workers in the 'wet tanneries' were recruited from among 'half-peasants' and for them, working in the tanneries outside their villages was not their only source of income. The Jews, on the other hand, would come to the factories in order to specialize in the trade and become master craftsmen who stood above the average workers and to collect some capital to establish a little tannery or other little business of their own. It is not surprising then that for the sake of ascent they all tried to please their employer and had never heard of labor unity.

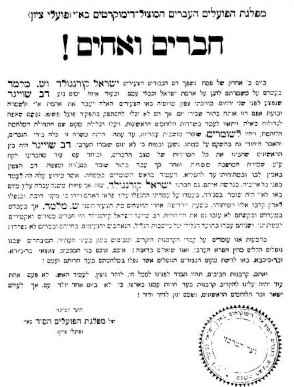

The average Jewish person considered work in the tanneries a lowly, hard and dirty trade. The workers smelled of the 'pleasant odor' of carrion and slack lime from afar. Krynki middle-class tanners did not tolerate this in the bes-medresh [synagogue and study house], so the workers built their own prayer house. The tannery workers separated themselves from their employers in the cultural-religious sphere as well and, as the Warsaw newspaper Hatsefira reported (see p. 264), they founded an association called Poalei Tzedek [Righteous Laborers] in 1894 whose approximately 400 members were all leather factory workers. The association intended to hire its own lecturer-teacher who would give the members daily Torah and Gemarah lessons in their bes-medresh.

The Bundist leader Sofia Dubnov-Erlich (daughter of the Jewish historian Shimon Dubnov and widow of the Polish Bundist leader and martyr Henrich Erlich) describes in her book The Tannery Workers' Union and the Brush Makers' Union (Warsaw, 1937) the typical young Jewish tannery worker of the Jewish Pale of Settlement. She writes that for the above-mentioned reasons “only those on the lowest steps of the social ladder would go to work in the tanneries. The tannery worker is the synonym of the ignoramus. A new type of factory worker started to gradually develop, at first in the Jewish quarter: the typical youth who was not diligent in Torah study but had mighty fists and a quarrelsome temperament. And this youth, with callus on his hands

[Page 66]

soaked in leather, gradually forces the others to treat him with respect.”

The first significant strike of the Jewish tannery workers broke out in 1894 in Vilnius, the hometown of tanning in the Pale of Settlement. Years earlier a German master craftsman had established in Vilnius a little tannery to tan horse skin into 'Hamburg' leather, a type of leather produced in Hamburg, Germany. Gradually other tanners learnt the trade from this German master craftsman (as we have seen, the first tanners were German in Krynki, too). Thanks to the tannery workers' strike in Vilnius, the local manufacturers raised the wages of the qualified workers and the echo of the strike spread in the tanneries of other towns as well.

By 1897 a few Krynki workers had witnessed organized strikes in Bialystok and Grodno. This affected many tannery workers in Krynki and their first strike broke out. It was a heavy and prolonged strike, which ended with the first victory of the workers: a twelve-hour working day and “wages to be received directly from the manufacturer”. This is how the brave and persistent fight of the Krynki tannery workers for humane working conditions started. “The Krynki workers”, continues Sofia Dubnov-Erlich, “placed the tannery workers in the first rows of the Jewish labor movement.” This was accompanied by a change in their way of life. “The tannery workers attained through their fight great improvements in their material circumstances and as a result their environment stopped treating them as pariahs. The parents among the artisan and petty trader started sending their children to work in the tanneries.”

The fight of the revolutionary workers although very significant was but one aspect of Krynki Jewish life in the period under discussion. Krynki was also a shtetl of Jewish tradition and Torah scholarship and even a prominent center in this regard.

In the period discussed, Rabbi Zalmen Sender Kahane Shapiro occupied the rabbinical chair of Krynki. A great Torah scholar of his generation and a prominent personality, he was respected and accepted by all strata of the town and his fame went well beyond the borders of Krynki. Rabbi Zalmen Sender had been rabbi in Maltsh and head of the well-known local yeshiva. When he came to Krynki, he brought a part of this yeshiva with him and continued to be its rosh yeshiva [head]. Even before his arrival, young yeshiva students from many Jewish settlements had come to Krynki to study Torah in groups. One of these students was Arye Leib Semiatzki who later became a distinguished Hebrew philologist and one of the most prominent editors of youth literature in Hebrew.

From the beginning of the 20th century until the entry of the Germans in town in 1915, part of the Krynki youth, just as many young Jews in the whole Pale of Settlement, underwent a certain degree of Russification. This was brought about partly by the few schools in town with Russian as the language of instruction and partly the Krynki high school students who studied in the Russian high schools of the nearby towns and, most importantly, by the general spirit and mood in certain strata of the Jewish population. Speaking in Russian and singing Russian songs with reverence was 'in vogue', especially among the intelligentsia and the 'upper' circles, just as well as reading the

[Page 67]

witty and freedom-loving liberal Russian literature which had a strong influence on them.

The Zionist movement started budding in Krynki in 1898 and it soon set about to transplant its ideas into practice, in particular through a national Jewish education. The basis of a Hebrew education was soon laid down and in due course Krynki distinguished itself in this Hebrew education and it brought excellent results later in forming a nationally minded Jewish youth, which made devoted pioneers for building Palestine.

In 1908 Yisroel Korngold, a member of the Poalei Zion, became known in Palestine and he soon immigrated there. He worked in the Jewish colonies first in Judea and later in Galilee and he was secretary of the party at the same time. He became a guard, one of the first members of the Hashomer organization (the predecessor of the Haganah) but he was soon killed by Arab bandits on Pesach 1909. He was one of the first victims of the Hashomer organization and of the Jewish community who sacrificed their lives for protecting Jewish lives and property in the future State of Israel.

|

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Krynki, Poland

Krynki, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 6 Mar 2022 by LA