|

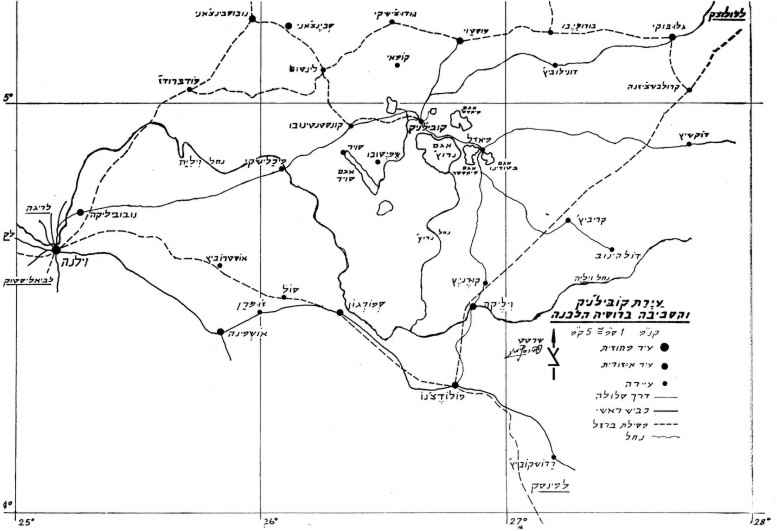

Town of Kobylnik

and its district in White Russia

| Scale 1 cm ≅ 5 km | |

| North ↑ | |

| ● | District city |

| • | Regular city |

| ∙ | Town |

| _____ | Paved Road |

| _____ | Main road |

| -------- | Railroad |

| ~~~~ | River |

|

|

[Page 23]

Moshe Kulbak

Translated by Joseph Leftwich

|

My Grandmother

When my grandmother died

When they lifted my grandmother from her bed,

My grandfather walked up and down the room,

When they bore her into the town,

Only when the Shamash took his knife, My Grandfather

My grandfather in Kobylnik is a plain man,

They float rafts on the river, haul timber from the forests,

My grandfather can hardly manage to crawl Grandfather Dies

My grandfather came home at night from the field,

My uncles and my father, his sons, stood silent,

And this is what grandfather said to his sons,

Rachmiel, who can compare with you in the meadow?

You, Samuel, man of the river,

Night was falling, the sunset glow

Then my grandfather drew his knees together,

A bird sang in the forest. |

[Page 24]

|

Town of Kobylnik

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

by Yitzchak Gordon of Haifa

Translated by Jerrold Landau

In memory of my dear mother Chaya–Musia Gordon.

Kobylnik, is a small town in Soviet Byelorussia (In earlier period, Jews called the district “Reisin”). From the 16th century to the third partition of Poland in 1795, it belonged to Lithuania and the Kingdom of Poland, which were united for 400 years.

After the partition, the district transferred to Russian hands during the rule of Ekaterina II (The Great). Russian rule lasted until the German conquest during the First World War, in 1915. During that war, the Germans occupied the town for about four years. Heavy battles between the opposing armies took place nearby. Kobylnik was under Polish rule during the inter–war period. The town was connected the Vilna region, Postów district. It was 105 kilometers from Vilna. It was on Lake Narach, one of the largest in Poland (with an area of 80 square km.), and on the Vilna–Polatsk Road.

A small river, which flowed into the Viliya River, passed through the town. Kobylnik served as the final stop on the narrow train that connected it with Lyntupy, as well as the broad train that went from Królewszczyzna, through Globky, to Vilna. The Russian–Polish border passed less than 100 kilometers east of the town. The border was broken by the Soviets in 1939, and Kobylnik passed to their rule. With the outbreak of the war between Germany and Russia in 1941, the town was conquered by the Germans, and remained under their yoke until the liberation by the Soviets in1944.

When exactly the town of Kobylnik was founded, what is the meaning of the name, and from where

[Page 26]

did its first settlers come? We do not have exact answers to these questions, and the facts are clouded in the fog of recent history.

Nevertheless, we do know the following from historical sources. Jews were already living in Western Europe from the first centuries of the millennium, having arrived via Rome. Other Jews reached Greece in earlier times, spreading to Constantinople and the Crimean Peninsula. However, they did not live in those places permanently, and their rights that they earned were dependent on the goodwill of the kings and nobility under whose protection they lived. From here we can perhaps surmise that the first Jews who came to Kobylnik area arrived because of persecution and deportations that they endured in their previous places of residence.

These persecutions lead to a migration of Jews from Western Europe to the east, which was populated by the Slavic nations. Jews reached the kingdom of Poland during the 13th century. In 1385, Poland and Lithuania united under the crown of King Władisław Jaggiełło. His cousin Witold was appointed as Grand Duke of Lithuania. During his wars with the Tatars, Witold expanded the borders of the country and reached southern Russia. He brought back Jews among his captives, and settled them in Byelorussia, Lithuania, and the vicinity of Vilna.

At the beginning of the 16th century, commerce with the lands of the west increased, especially in the export of agricultural and forestry products. The estate owners, who were not proficient in administrative business, looked for talented people to manage their businesses. They found the Jews to be fitting and appropriate in this area. Even though the Polish nobility was suffused with hatred toward the Jews, and related to them with disdain, they did not refrain from using them as a force against the city dwellers (Meisczinim) to weaken their influence.

Indeed, during that era there were Jews who left the royal cities and accepted the role of managing the estates and farms of the nobility. Others leased the tax depots and the tollbooths at intersections and rivers, which served as sources of income for the landowners. Jews owned taverns and inns in the areas between cities (Krechemes). Such a krecheme[1] is known to all of us in Kobylnik. It stood near the center of the town. Thy leased the mills, the milk business, the taverns, the fish ponds, the wineries, the orchards, and the like from the landowners. There were also Jews who obtained the rights to move mail from place to place (“Poszters: we all recall, for example, Bentze the Poszter, who lived in our town before the First World War). In addition to all this, Jews were also involved the grain, flax, and pig hair trade in the villages, as well as in the selling of haberdashery to the residents. This is how the Jews and their business endeavors spread in the villages and estates. At that time,

[Page 27]

official towns were formed from settlements that had once been “private” towns of estate landowners. Most of these towns were named for the landowners and nobility.

|

|

We have found evidence for these names through the names of the towns near Kobylnik. The names identify the family names of the landowners (boyars) of the area. Even our town of Kobylnik is named for a landowner named Kobylnicki. The landowners to whom the towns belonged granted Jews the rights to establish synagogues, inns for housing the poor, bathhouses, Jewish cemeteries, and other institutions that were necessary to conduct communal life in the towns.

The growth of these towns came primarily through the charters that were issued against the Jews during the rule of King Alexander I in 1804. The Jews were ordered to leave the villages in which they lived and move to towns. The deported villagers led to crowding and a rapid growth in the Jewish population of the towns. We find testimony to such from our times: Many Jews who lived in Kobylnik are called by names

[Page 28]

related to the nearby villages in which they had previously lived. For example, my father of blessed memory was called Avrahamel the Moczanier. Others were called Yisrael the Pasinker, Meir the Skarier, Shlomo the Szloker, Leibe the Wirenker, Zalman the Hatowiczer, Yisrael the Kuper, etc.

In maps from the era of the “Lublin Unia” (the uniting of Poland and Lithuania in 1569), we find that in the district in which our town of Kobylnik exists, there were already towns such as: Globoky, Dolhinov, Smorgon, Oszmina, Radishkowce, etc. Even if we do not find Kobylnik on that map, we can surmise that the history of our town also began from that period. Support for this theory can be found in the Geographical lexicon of Poland, published in Warsaw in 1883, in which the following is written about Kobylnik: “During the 16th century, Kobylnik belonged to the Duchy of Greater Lithuania, and was owned by the nobility of the Zaborsky family. Later, it was transferred to the ownership of the Abrahamowicz family. Ludwig Bakszt Chominski, a writer and land registrar in the Duchy of Greater Lithuania sold Kobylnik to Marcin Oskrako, the prince of the palace of Oszmina. Later, Kobylnik was sold to Antony Swintorczki. In 1866 we find that, aside from the Swintorczki family, two other families of nobility had ownership in Kobylnik: Zybmunt Sziszko and Wansowicz.

Even though we have found general historical material on Kobylnik starting from the 16t century, we have not found any material confirming that Jews lived there during that time. We know about the existence of Jews in the town only from the 19th century. In the Yevreiska Encyclopedia, published approximately 100 years ago in Peterburg, the following is written about Kobylnik: “In 1847, the Jewish population of Kobylnik was 140. Fifty years later, in 1897, the general population was 1,055, including 591 Jews.” In the aforementioned Geographic Lexicon, we find that the general population of Kobylnik was 370, including both Jews and gentiles. This number included 190 Catholics, 164 Jews, 7 Pravoslavs, 6 Muslims, and 4 families of “Strobirs. “

In the continuation of the same source, it states that Count Swirski built a wooden church for the Christians in 1651. It also states that there were five annual fairs in the town. In 1966, the district of Kobylnik includes also

[Page 29]

Swirani, Wierenki, and Chomiki. It had 315 houses, 67 agricultural settlements, and a population of 3,487 farmers.

In various times Kobylnik served as an export depot for lumber, via barges on the Narach River. In the nearby village of Sciepieniewo, which is surrounded by large, thick forests, they would cut down the trees (especially the large pine trees), collect them on a hill on the banks of the river, and roll the large trunks into the water at an opportunity time. They would tie them into barges, and float them to distant places.

The barge drivers put up a tent in that area, which served as a sleeping place and a kitchen. Through the efforts of the drivers, and by rowing day and night, they floated the lumber eastward until the source of Narach River. From there, they lumber floated down the river until it reached the Viliya River, upon which the city of Vilna was situated.

In Vilna, they would take the lumber to a sawmill close to the city. The planks of lumber were used in the carpentry shops and factories for the manufacture of wood products for use within the country, and for the provision of wood products for export abroad.

|

|

Translator's Footnote

|

by Meir Yavnai (Yavnovich)

Translated by Gilad Petranker

Edited by Toby Bird

A commemoration for my parents, my sister, my brother and their families who have perished in the Holocaust

Yamim Noraim – The High Holidays are at hand

The month of Elul in our town – as in all Jewish towns that have woven together the special Jewish way of life – moved the hearts of every Jew, young and old, man and woman. The hot summer sun, shining with all its might, brought peace to the entire universe. The wheat ripened; the fruit trees were heavy with fruit that ripened from day to day, and enjoyed the blessing of the sun from above and suckled the essence of life from the ground with their roots. From a distance echoed the doleful song of the harvesters – a song that heralded the approaching of the gloomy autumn days and the end of summer's glory. In the warm and delicate air, a thousand thin threads were woven, like the webs of a spider, which the rays of the sun made silver with their light. These threads were called colloquially “a woman's summer.”

It seemed as if this summer peace would never be disrupted. The heart envisioned it as everlasting, imperishable. But early in the morning on the first days of Elul, the town – which had been sleeping and snuggling against the calming serenity of the late summer – was alarmed by the sound of a Shofar blasting lengthily, like a cry, awakening the sleepy hearts and calling them to repent, the hearts submerged in their slumber and enjoying the bright light of this blessed world. This blast moved the heart of every Jew. It announced that it is time for introspection; that the day of judgement is nigh. It cried to us to detach from the vanities of this world and to call for repentance, to face accusing Satan and to equip oneself, facing the Creator who gives life to every living being, with a sack of good deeds and acts of kindness.

And while the entire world is sleeping, and the night's chill of an approaching autumn covers the universe, doors would open and figures would slip away through them, with the sleep still clinging to their eyelids, and all their limbs still weary and craving rest. The warmth of their beds hasn't gone from them. And these figures would gather within the walls of the synagogue. The candles and the gas lamps were lit, and their light broke through the dark of the departing night. From afar rose the voices of children, begging to their Father in heaven: “Oh oh, merciful God, saving His grace unto thousands.” In this refrain the voices rose and spread throughout the town which was still asleep. These voices would wake me from my sleep since I was too young to take part in saying the penitential prayers, and perhaps my will was not strong enough in those days to give up the hours of sleep just before sunrise, which are so sweet. Morning came. Each man would return home, carrying the bag of tefillin and tallit under his arm, and in his heart the hope that the prayer sent indeed would reach its destination and would perform the mission it had. And from holiday to weekday – the working day returns. The shops open; everyone goes about their business, to sell and buy, to haggle and bargain. But each one had in his heart the secret of sanctity as well as the hope that the sacred overcomes the secular, good overcomes evil, the advocate of truth overcomes accusing Satan.

Rosh Ha'Shana (New Year)

With the days of Elul approaching their end, the commotion in town grew towards the High Holidays. Their awe was felt everywhere. The number of people waking early to pray grew every day and the voice of people in prayer grew as well. The blast of the Shofar, which pierced the stillness of the universe before sunrise, increased the quivering of the heart and demonstrated more fiercely the approach of the deciding hours.

On the eve of Rosh Ha'Shana the prayer in the synagogue was longer than any other day. Inside the houses, the housewives diligently made their last preparations toward the holiday. The scent of the special food for the High Holidays was carried through the air. The ladder–shaped Challah bread was baked, for the prayers and wishes to ascend to heaven. Care was given to the bowls of honey, brought to the table to taste from, so that the year to come would be as sweet. A slice of watermelon was prepared, called “Kavineh,” which had seeds peeking out like black eyes. Everything was scrubbed and polished in silence and moderation, befitting the upcoming serious moments. And when evening came, everyone hurried to the synagogue, illuminated with many candles, in memory of the people gone, whose memory would be mentioned the next day during the “Yizkor” prayer.

And the people pray, wrapped in their white Kittels (robes) and their books of prayer on the prayer stand before them, ready for the signal given by the prayer leader. The prayer pours out in the special melody of the High Holidays, all of which is sadness and purification in the face of the Creator – a melody of crying and supplication, momentarily changing into embellishment expressing joy of hope and security, ending with the blessings of “may you be written for a good year” and “so may you” – leaving the synagogue after the Arvit, after the “first knock” that was sent to the Gate of Mercy, and hurriedly returning to their homes to the festive and solemn dinner. They taste the honey and the special fruit and with an anxious yet hopeful heart they retreat to a night's rest before the next day, toward more penitence with the Creator.

And the next day, early in the morning, again, they flow to the synagogue. After the Shaharit comes the solemn moment when the prayer recited is “The King,” and the fear of the King is felt all around; the fear of the judgment day becomes more tangible. And that fear rises and reaches its peak when the prayer is “Unetanneh Tokef” – “Let us speak of the awesomeness” – who for life and who for death, who by famine and who by thirst, who by sword and who by fire. Broken cries pierce through the wailing of the prayer leader; bitter sobbing of women comes from the ladies' section in hearing the horrible words. And with a pronounced emphasis, the entire congregation's voices follow the cantor, the words planting security in everybody's hearts: “and prayer and penance and charity pass over the harsh fate.” And when the hour of blasting the Shofar is near, again the solemnity and the heaviness of the occasion grow. When everybody wraps their tallit around their heads and stand on their feet – the sounds of the Shofar pierce the awe–struck silence encompassing everything. Appeased and calm, everybody continues praying until noon. Jews return to their homes with a recovered stride with a solemn countenance. With the blessing of “May you be inscribed for a good year,” they enter their homes for the lunch of the Rosh Ha'Shana.

After gathering strength, they would go before sundown to the river for the “Tashlikh.” While reciting the prayer “And you will cast all our sins into the depths of the sea” they would shake the pockets of their garments to symbolize the shaking off of all sins and the tossing of all faults to the depths of the river, so that the current would carry them to unknown distances.

And again the Arvit arrives, and the next day would be the second day of the Rosh Ha'Shana, like the first day. The days of the Rosh Ha'Shana have ended, the two first days of the High Holidays, and the Ten Days of Repentance begin, leading up to the most awesome day of all – Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement.

The Ten Days of Repentance and Yom Kippur

And between the Rosh Ha'Shana and Yom Kippur, between the new moon and the tenth day of the month, grows the air of repentance, prayer and charity. The droning of prayer becomes the basic tone of these days. It's voice is carried in the mornings through all the streets and yards near the synagogue, and these sounds bring with them a sort of sadness to the heart, along with the sadness of the days of autumn, boldly approaching.

And the days grow short. The doleful song of the harvesters at dusk joins the minor harmony, mantling the sadness. Women wearing headscarves and with eyes full of tears hurry beyond the bridge and disappear on the narrow path going between the yards of the gentiles – the Goyim – leading to the cemetery. There they stretch over the graves of their dear ones and call unto them with bitter sobbing or with quiet and broken weeping, to stand at their side at the deciding moments of the verdict. Their lips silently move, pouring out the wishes of their hearts, to come up before their Creator.

The hand opens generously, giving charity to every pauper and person in need. And on the Shabbat between Rosh Ha'Shana and Yom Kippur, the Shabbat of Repentance, the Jews swarm to the synagogue after a short afternoon nap, to hear the sermon of the rabbi about the matter of the day, that is repentance and the fear of the days. And the rabbi would weave into his words sayings of the old sages and parables, along with legends from days of old and stories from more recent times – and all of them are directed at evoking thoughts of repentance and regret, since the modern time has led us astray.

And on the night before Yom Kippur comes the shrieking of roosters from every Jewish home, from the attics or from the alcoves of stoves, roosters which have been disturbed, taken out of their places and tied up for Kapparot – atonement. With a heart full of faith, Jews – old and young, men and women – swing the rooster above their heads and their lips move silently with deep intent: “Men dwelling in darkness and the shadow of death… this is my atonement, this will go to death and I will go to a long and good life, Amen.” And from the yard of the Shochet –the butcher – echo the last chords of these poor birds, who are slaughtered for the atonement of the humans, and for the feast ending the tiresome exhausting fast.

At the eve of Yom Kippur, the town resembled a camp that was called for duty. Every deed and every step, the keeping of each and every detail in custom and tradition kept for generations, were directed into a single purpose – to take away the harsh fate, to add floor above floor to the building called Teshuva – repentance, a building which was started on the first day of the month of Elul. And again, the ladder shaped Challah bread was baked. And it was a custom to eat exceedingly before the fast, as it was a Mitzva to hold the fast. And special Jewish cuisines were brought to the table: bowls of soup with meat–filled dumplings and the ladder–shaped Challah. And again, a meal – and they would hurry to the public bath house to cleanse the body well before the day of judgement.

And from house to house the Jews would pass to ask for forgiveness for offences that had hurt somebody's dignity during the year. Bitter rivals who would not exchange a word during the year would make peace on that day. With a serious countenance and an air of importance, the heads of the families would sit themselves at the table for the final meal before the fast, an early meal.

And when they finished eating the delicacies that were carefully prepared, all the members of the family would hurry to the synagogue for the Minha and the “Kol Nidre” prayer. The entire town, even though it was not wholly Jewish, wore the air of Yom Kippur. Even the Goyim felt that during this day, something serious was taking place in the homes of the Jews and, especially, in the synagogue.

And the memorial candles would be brought to the synagogue to be lit. Jews would take off their shoes and would wrap themselves with their Kittles. At the entrance to the synagogue they would put up tables with bowls for charity with signs next to them. In recent years, the bowl of the Jewish National fund appeared next to the other bowls. Everybody saw a holy and exalted duty to donate to the different bowls of charity, each one according to his ability and perhaps above that. The floor of the synagogue was covered in dry hay, letting off its special scent, the scent of a field.

The beadle of the synagogue, the Shamash rabbi Shaya–Yosef would walk around in a manner of dignity, wrapped in his white Kittle and carry a strap, which he used to adminster the customary whips to whomever desired them. Jews would stretch themselves on the floor in front of him, kneeling, and he would count to forty minus one.

The dark would descend over the town. The candles and lamps would shine around. The congregation would hurry to its place. The set of prayers would begin, starting with a whispered “Be'Tfillah Zaka” – “in a pure prayer.”

The hour of “Kol Nidre” is approaching. At the entrance to the synagogue, by the door and in the entrance hall, some of the Christians gather up as well, to witness the “awes of this night.” Among the people gathering are the dignitaries of the town: the head of police, the head of council, important officials etc. and I remember the hearts of the children would be proud – here, even the Goyim would honor us with visiting the synagogue on this day.

The Shamash would beat on the table of the platform. The “Kol Nidre” prayer is recited with its traditional melody in the breathless silence. The congregation joins the cantor. The Torah scrolls are taken out of the Torah Ark in awe and reverence. The words “Light is sown for the righteous, and gladness for the upright in heart” are heard and from this point the entire congregation would gradually take a more active part in the prayer. The voice of the cantor and of the entire congregation blend with each other. The doleful and pleasant melodies are sung by everyone. The “Yaalu Tachanuneinu” prayer, “May our supplications ascend at eventide; our pleas come in the morning,” purifies the heart and soothes; and the prayer approaches its end.

Some of the people praying stay in the synagogue to stand in their place – the place of connection with their Creator – during the entire night, and most of the congregation leaves. Sometimes a light rain, heralding the coming autumn, would start trickling. It seemed as though nature added its bleakness to the bleakness of the moment, accentuating the seriousness of those returning home from the prayer of Yom Kippur. And with total silence they would depart from each other with the blessing of “Le'Shana Tova Techatemu,” “For a good year you shall be confirmed,” and disappear into the darkly illuminated houses. Bit by bit they would go to the night's rest, to gather strength for the next day, the day of fasting and torment, the long day of prayer from morning till night.

And early in the morning the synagogue would again be filled with people praying. After the ordinary Shaharit, the people in front of the ark would be replaced. The intended cantor would take his place by the ark. “The King” is trilled by the cantor, and the congregation joins him with the traditional melody of the High Holidays. Bit by bit the words of the people pour out, the prayers are loudly recited – sitting down and standing up – and again the congregation is called up during the Musaf prayer when the cantor opens with “Unetanneh Tokef.” And with describing the tribulations expecting man, the crying is fiercer than that of Rosh Ha'Shana, all according to the will of the Almighty. Low and heartbreaking wails come from the ladies' section. Children with their curious eyes search for their mothers to see them by the narrow openings in the attic, where they pour their words to the Creator. Their wails grow with the mention of the dead. Some of the people hurry home after an additional Musaf prayer to rest a bit and gather strength.

After the Minha, the marks of the fast are seen everywhere; signs of fatigue and paleness are on the faces, but it seems that everybody is feeling relieved. A pleasant weariness is prevalent as well as the satisfaction of those who have done their work honestly. And maybe the emotion, like a child's, that has been reconciled with his father filled the hearts of the congregation at that time. And in those moments of quiet everyone sits, rests and anticipates the song that has become a part of the tradition of Yom Kippur, like an intermezzo between the Minha and the concluding prayer, the Ne'ila. In a deep and pleasant voice, Rabbi Eliezer, with the gray–streaked black beard, starts singing with a kind smile spreading over his face, and the congregation follows suit, from one melody to the other – the songs would flow heartily and slowly and even “Ha'Tikva” was in repertoire of recent years, if my memory does not mislead me.

The evening has settled. It's time for the Ne'ila. Again, a time of solemnity, but softer than in the commencing of the fast. With renewed energy and with a new hope, takes place the last charge on the Gate of Mercy: “Open a gate for us at the time of the locking of the gate,” flows the pleasant voice of the cantor and the congregation. A last request is sent to heaven, before the verdict is sealed. Everybody believes and hopes that the harsh fate is removed, that the prayer and everything done will bear the desired fruit.

And the blast of the Shofar is encouraging and brings hope: a hasty Arvit with “Next year in Jerusalem,” the blessing of “Gmar Khtima Tova,” “May you be written and confirmed.” While leaving the synagogue they quickly bless the moon, and in tired steps the Jews go home to the meal after the fast. In everyone's heart there is a feeling of leaving a heavy burden behind.

Sukkot

And already at the parting of the holiday, after the end of the meal, lanterns were flashing in the yards of the houses: Jews were busy fixing the first pillar for the Sukkah about to be erected on the days between Yom Kippur and Sukkot.

The preparations for the holiday are performed in happiness, feeling relieved after the solemn days fearing judgement. How happy were the children of Israel in those days, especially while erecting the Sukkah. Who could forget the joy of taking part in the work?! So diligently and willfully the toddlers of Israel would present to their father a beam, a pillar or a nail, who was busy with erecting the Sukkah! How joyful would the heart be, in sight of the green canopy, the Schach, that was brought in a wagon from the forest by the Goy or by the eldest son on his own, if he owned a wagon and a horse. The scent of the forest would spread and a homely warmth would enfold everything, when we would huddle between the four shaky walls roofed by the Schach. And the children would rush to cover the floor with yellow sand and the housewife would decorate the walls with anything befitting decoration. A table would be put in, benches or a few chairs. The table would be covered with a white tablecloth, and how great was the anticipation of the children for the evening, for the first dinner in the Sukkah, with the stars winking from above through the crack in the Schach. And anxious would the heart be, that the sitting in the Sukkah would be interrupted by rain, since the time of autumn was at hand and its presence was felt in the air; and more than once the rain poured down on the very first day of Sukkot.

And obviously there is no holiday celebration without a festive prayer. And Jews would stream into the synagogue fresh and with renewed energy, their faces shining, and in their hearts the joy of holiday. The prayer ends with a jolly melody, expressing the joy in the heart. And with the greeting of “Happy holiday,” “Good holiday,” they would hurry home to the illuminated Sukkah, the family atmosphere, the special holiday cuisines served in the Sukkah. The sound of festive songs breaks out from the meagre looking Sukkot, but a stranger would not understand the elation and the holiday joy filing these four walls from within, covered with branches of fir and willow.

The seven Ushpizin – the Sukkah guests – are invited to come. The children fall asleep and are taken into the house. Another long time passes with the songs and special prayers sounding through the night. It seemed that the world has returned to the wandering of the Israelites through the desert, when they sat in their Sukkot on the journey back to their land.

It's morning. Again, the town wakes up to life. Rabbi Shaya–Yosef is dressed in his black robe, the Bekishe, and his silvery quivers in the wind. In one of his hands he holds a box padded with strands of linen with the Etrog, the citrus fruit, and in his other hand he holds the Lulav, the young palm tree frond, surrounded by branches of myrtle and willow – Hadass and Arava – tied to palm tree branches with strands from last year's Lulav. And how wonderful that Lulav would be for us, the children! I can still remember to this very day: with shaking hands, we would hold the Etrog and the Lulav, Rabbi Shaya–Yosef would say the blessing, and we would repeat and delightfully shake the Lulav to the four winds. Mother is also called from the kitchen to fulfill the Mitzva of blessing the Etrog and Lulav; the rest of the adults hurry up to fulfill the Mitzva as well, and Rabbi Shaya–Yosef leaves the house and goes on to visit other houses.

Now there are the days of Chol Ha'Moed, the intermediate days of the holiday. The rains often pour, heralding the approaching winter, but the air of the holiday still lingers, reigning supreme. A strange chord steals its way into the air of the holiday, a chord forgotten with the passing of Yom Kippur – the day of Hoshana Rabba, the seventh day of Sukkot, which is approaching. We children know – from listening to the grownups – that on that day there is still hope to remove the harsh fate that has been sealed on Yom Kippur. The children delight on this day in the special occupation it summons: the picking of branches of willow trees and arranging them into bunches for the day of Hoshana Rabba.

In the chilly and foggy morning, we would awaken and go to the river and the forest to pick these branches. On the way, we would visit the chestnut trees which would shed their fruit at night. How we would delight with that fruit, still in its green shell which had cracked when the fruit fell from the tree. We would find the fresh colors charming, the brown and the white. This fruit, when still smooth and fresh, would get collected like a precious treasure into our pockets and fill our hearts with endless joy. And from the tree to the main purpose – picking the willow branches. Heavily laden we would return to the town and supply the branches in small bunches to anyone who would desire them, to whip them during the prayer. “Please God, sav – sounds the cantor, and it's time to whip the branches. The whipping sounds fill the space of the synagogue, and the children join the Mitzva with all their hearts and their childish innocence.

And at home, special cuisines are served: again, dumplings like on the eve of Yom Kippur, a white Challah bread, etc. Bit by bit we enjoy the blessing of the holiday, fearing every passing moment. But the main part of the holiday, its center, is still ahead: after the celebration of Beit Ha'Shoeva – which was a big deal, especially for the grownups, and for us children was not completely clear – would come a day all good, filled with the joy of the Torah, a day which we had been anticipating, Simchat Torah. Who will not remember the flag, preparing the stick for the flag and crowning it with a hollow carrot or an apple, a base for the candle?! And unlike nowadays, how many hardships did a boy in town have in obtaining the flag and stick! And undoubtedly that was why it was so pleasing and joyful to have gotten it. We anticipated the fall of the evening, the time for the rounds– the Hakafot– the real reveling in the Torah. Everybody would pride himself in his fancy outfit and flag. The candles would be lit. The flags wave on the hands of children, shaking with joy and fearing the safety of their goods.

Simchat Torah

The synagogue was bathing in a sea of lights, hustling and bustling with people. On this day, the women were allowed to mingle with the crowd. Women, children, toddlers – all stuffed together, with the joy of the holiday gleaming from their faces. The toddlers are carried up, lifted high so they could see what's taking place. The Shamash Shaya–Yosef is running around gleaming, radiating holiday and joy. The prayers are said with joy. Everything is tense for the bringing out of the Torah scrolls – the Hakafot. The verses of “Ata horeta lada'at”– “Unto you it was shown” – are festively said. The scrolls are taken out and given out to the crowd. The first round starts. The first one parading recites the right verse, and after him come the carriers of the scrolls. Some carry a scroll in one hand, and in the other hand – a little boy. The people going around dance and sing. The crowd all around kisses the scrolls, touching them with a finger and then kissing the finger – kissing the Torah through the finger… and who could forget the rising excitement, the growing joy, and many pranks pulled by the adults, many of whom came to the synagogue properly drunk. Drunk Jews – do not think lightly of it. And the rounds go on and become a whirlwind of circling feet, running and dancing. Everything is swept away with the current of joy and celebration. And I remember, a light sadness would always slip into this joy of mine – worrying about the approaching end of joy.

The next day the synagogue is full of glee again; rounds, and ascending to the Torah: the ascent of the Chatan Torah, the groom of the Torah, the ascent of the children, wrapping themselves with one joined Tallit – “with all of the boys” – and then splitting into Minyans, groups of ten. The Torah scrolls are taken out of the synagogue and into private houses, to Minyans. Proudly and with a calm of holiday, Jews accompany the scroll carried in the hands of one among them to his house. There they spice up the joy of the holiday with brandy and cookies. We remember the stories of the elders, of the true holiday joy that they had seen at their time, when Jews who would be serious year–round, would go from house to house, break open the stoves and take the holiday foods to bring to the town's market square, where they would serve them to the drunken feasters on a yard's gate, that had been taken off its hinges. The food would be eaten, washed down with drinks, and the Jews would break into dance, before the eyes of a crowd of curious people, among which even Goyim would watch.

But we heard of that only from the stories; we did not see with our own eyes. And we remember the joy in the houses. After prayer, groups of Jews would gather, mostly relatives and friends, from the same circle. They would go from house to house and sit around tables set with food and drink, and the drink would be guzzled. “Cheers, Yidden (Jews), cheers!” The housewife would happily serve and everyone would harass one of the drunkards, wanting to see him in his disgrace – then give him cup after cup enjoying his looks and delighting in his senseless drunken talk.

Bit by bit they would scatter to their homes with the family dinner still to come. What magic these moments had! How much the strong connection stood out between the members of the family, between related families, and the whole of Israel. On that day, all the quarrels and fights of the entire year would be forgotten. Enemies and rivals would kiss and the memory of their animosity would vanish, as if it had never existed.

As mentioned, this was a day entirely good, a day of Simchat Torah, the joy of the Jewish person, invested throughout the year with the worries and the burden of livelihood, the trouble of the individual and the whole of Israel. It was such a pity that the day did not stay longer, and with its end came the concern to town, that was brought by the approaching cold winter: wood for fire, warm clothing, stocking potatoes and storing them for the cold days of winter, keeping the apartment against the cold etc., etc. And children were obligated to go back to the “Cheder,” the class, after the High Holiday and Sukkot, for the long winter period. Again, being confined in the narrow room from morning till evening, to part with the willows of the river, the charming chestnuts, the wild pears that were piled in crates or in piles, and were stocked in the attic on the dry hay.

The days of rain, a Polish autumn: the mud covers every street, path and trail. Unwelcome days, an autumn sadness veils the meager and bent houses of the town. As if it were from the whipping of the raindrops on their roofs, it seems that these houses are even more sagging. The days grow shorter and the nights are long, endless, infinite. Only once in a while does life pierce through the dark of the clouds and push away the bleakness of the world.

One morning the entire universe wakes up and everything is clothed in white, a cover of snow. The black of the mud is covered in white. The trees are coated with a white cover, the roofs are white and mischievous boys go out to roll up the clumps of snow that was piled overnight and to make it into a snowman. Others have snowball fights, with a mischievous and gleeful spirit. On the street, the sleigh is seen instead of the wagon, which until yesterday had its wheels sunken in mud. The snowflakes keep falling ceaselessly. People clothed in furs or winter coats, wearing boots are seen treading through the snow – winter took hold of the town. The frost, the cold, grow from day to day. The snow creaks underfoot. Sometimes a snowstorm breaks, and no one leaves home. People abundantly feed the stoves and keep warm by them. The double–glazed windows are taken down from the attic and are set in their frames, with the gap between them filled with sand. The cracks are covered with strips of paper and only here and there is an opening left to keep the apartment aired. In the evenings, the housewives sit and knit, weave and repair a sock by the light of the gas lantern and the warmth of the stove. The men gather for the game of cards, which started spreading through the town like an unwanted plague.

On the market days, the town is filed with life. The tracks of the wagons, man and beast soil the white mantle which wrapped the town during the week, but the next day everything will be covered in white again. The trees stand with white robes. Early in the morning white smoke rises from the chimneys in the roofs of the houses; in the chill of the morning the housewives hurry to the well to draw water from the wells, surrounded by hills of ice, so much that the people carrying the water are in danger of slipping. Sometimes the men go and dig through the ice, to allow access to the well. Here and there a sleigh is seen laden with barrels of laundry, hurrying to the river, where they would dig through the ice down to the water, to rinse the undergarments that were laboriously washed at home.

The children of Israel hurry to the Cheder to study from the mouth of their Rabbi. Unlike the days of summer, they are confined to the narrow room for a whole day and strain their minds and talents to come up with various excuses to go out and cause some mischief. At noon, they hurry home for lunch and will come back carrying lanterns with candles inside, to light their way home at dark late at night, through the dark alleys. On the short recesses they go out to have snow fights or slip away to skate on the ice–covered river.

From Sukkot to Hanukah there is no holiday, apart from the Shabbats which will partly be dedicated to prayer and an exam in the Torah that they had learned in the Cheder by their fathers.

Hanukah

A few days before Hanukah the efforts would be to start to get hold of a Dreidel and a few pennies to play. Even cards would not be deemed too lowly if they could only be found. Some try to melt zinc or tin into a wooden mold, to make a Dreidel – but mostly that would not be fit for playing, and they would settle for a wooden dreidel. The menorahs are taken out of their hiding place; bunches of candles appear in the house.

The first Hanukah candle was lit in the windows of the houses. The blessing of the lighting of the candles, “Ha'nreot halalu” and “Maoz tzur yeshuati,” are sung by the father, and from the kitchen spreads the smell of the latkes fried in goose fat, which were fattened for weeks and slaughtered a few days before Hanukah, to collect the fried fat and its fried dried bits called Gribenes. Guests are invited to the festive latke feast, and the game of cards, which becomes these days a game acceptable by every Jew, occupies all the members of the family as well as those coming for the feast. And obviously those who have been playing cards all through the winter's evenings keep themselves busy on the nights of Hanukah and stay up late. Sometimes one of the card players might return home to meet the curses and scolding of his wife, for losing his last pennies and so deprived the house of its many urgent needs. More than once this late–night meeting would end with a loud fight between the husband and wife, which would fuel the gossip the next day of those hunting for sensations in the vacancy of town.

Anyone going through the streets of town at night on the nights of Hanukah will see the flames, flickering through the windows of the Jews, piercing the white cover of the glass. The candles of the menorah would wake the warmth of the days of old in the heart, tell of the miracles and the wonders that were done to our forefathers in those days and today.

The eight days of Hanukah have passed and the town goes back to the everyday sleepy winter life, and the mundane businesses, the worries of livelihood, replenishing the wood for the stove that had become scanty through the first months of winter. On these days Shaya–Yosef can be seen slowly striding through the snowy streets, going from house to house to collect the few pennies for the poor, for medical needs and for heating up the houses of the needy. Bit by bit his frozen, shaky hands would write the donation of the week in the wrinkled notebook.

On the 15th of Kislev, there is much commotion among the members of Chevrah Kadisha, holding the annual feast in memory of Rabbi Shneur Zalman coming out of prison. As a boy I couldn't have understood back then – what the business was of this celebration, this feast and these delicacies abundantly given to the people who deal with burying the dead. The happiness of the people who do such bleak work which horrifies both old and young could not be resolved in the minds of the town's children and seemed unbecoming to their work– the work of burying and cleansing of the dead. “Amcha,” simple people who did not have the honor of a decent ascent to Torah or a decent place in the synagogue are exalted on this feast, feeling their importance and guzzling the wine until they are drunk, feasting on the many delicacies that were abundantly prepared and which, perhaps, only at this time of year they will be able to enjoy.

And from holiday to weekday. Up until Tu Bi'shvat, the 15th of the month, was a day whose importance only the children in the Cheder felt, with the taste of dried up shriveled carobs and a few almonds which were said to have come from Eretz Israel. In their imagination, they would strain to float from the cold land of frost to the land of warmth, where on this day would be the trees' new year.

Purim

But compared to the dullness of this day, Tu Bi'shvat, the coming of Purim was really felt in town. Sometimes its coming was heralded by the winds of spring, which started blowing through the world, thawing the “candles” of ice hanging from the cornices of the houses. The children expect this day with anticipation, and rushed to equip themselves with various weapons against the bitter foe, Haman. All their talents and tricks were mustered to get hold of the gunpowder, the pistons, the keys and nails, the matches, the rattlers and all the other props.

It's the evening of the reading of the scroll in the synagogue. Set for battle, the mischievous children wait for the reading of the scroll, their ears anticipating the uttering of the name Haman from the reader of the scroll in the traditional melody. When the name is all but uttered, a bellowing thunder of shots and various tools and weapons fill the entire synagogue. And the weapons would be re–armed for the next round… smoke would fill up the synagogue, and joy would fill the hearts of the children of Israel, since they were given – and not often did they have this privilege – to deliver all their mischief with permission, in public and uninterrupted. And the louder, the better. And the next morning the whole scene would repeat itself. I think only the day of Simchat Torah might compete with the day of Purim in the glee it would fill in the hearts of all, especially those of the town's children.

And neither would the adults withhold themselves. The preparations would be made beforehand, for the Mishloach Manot – the sending out of food as gifts– and for the feast of Purim. The feet of those carrying the plate, the bowl of the Mishloach Manot, were treading through the snow, melting slowly on the town's streets, from house to house. And the bowl would be filled with coins: money for the main people who would send out the Mishloach Manot, such as the rabbi, the Shamash and the Shochet, who had the Mishloach Manot as one of the sources of their meager livelihood.

On the feast of Purim, the relatives and friends would gather, drinking and eating, and everyone would be merry and joyful with the air of brotherhood, with the air of a whole Jewish celebration, which did not frequent the hearts and homes of the town's Jews who would be burdened with the worries of livelihood and surrounded by the hatred of Goyim and bitter foes. The memory of that miracle, the memory of Haman's downfall, warmed the hearts of all and brought hope and faith, that that would be the end of all the foes and accusers who rise against us every generation. Even the spring weather added its warmth to the heart, which had become frozen during the long days of winter in the chill and frost. And Passover would be winking from afar, approaching, the holiday of our liberty, coming out of slavery into liberty, the holiday of the Matzos.

Passover

And immediately after Purim the preparations would start for the Passover, that is to the main issue of the holiday – preparing the Matzos for baking, as was the custom in many towns of Israel in those days, manually and together, with mutual help: “Fodredn.” And there would no other days like this – with the winds of spring, the melting of the snow, the frost and the ice covering the river – to warm the hearts of the town's Jews, to arouse hidden and unconscious hopes, to encourage them and strengthen them in the harsh war of survival.

But we'll go back to the commotion toward Passover and first and foremost, the baking of the Matzos. The town's people would divide into groups and would agree upon the baking to take place in one of their houses, with a big enough baking oven, and with ample room for all of those taking part in the baking, that is, the dough kneaders, the water pourers, the flour spillers, the Matzah piercers with the dough docker, and the baker, who puts the Matzos in the oven and removes them, and the disperser of the dough, called in Yiddish ”Der Meyre Halter.” And when they would all agree they would also set the time and place to bake a Matzah Shmurah – a guarded Matzah – a task which was done by men who were specially trained.

And how much joy did the children of town have. Here is a holiday coming, here– in a few days they would be free from the Cheder two weeks before the holiday, free to run to the river to witness the thawing of the ice and the cracks forming in it, and the blocks of ice carried away with the rising water, going up from day to day, putting the inhabitants of both banks in danger. And how great it would be to join the grown–ups in the “fodred” and help with the work of baking the Matzos, according to the capacity and age of each one. The young ones, who had been doing this Mitzva for the first time, get the more minor jobs which they view as important as a rung in the works' ladder.

And this was the order of work according to their value and importance: pouring water and flour into the basin– the first rung in the ladder and the least important. A more respectable level – the Meyre Halter, meaning the dough holder – sitting at the head of the table and dispersing bits of it to the women and girls to roll on the long tables until they become round and flat Matzos. Another level, with doubtful importance, is the receiving of the flattened Matzah from the kneaders and bringing it on a round piece of wood to the table of the docker to be pierced and then to the baking room. By the way, this role was dangerous, since any toddler who might drop the Matzah on the way to the table, or if he would stumble on the bread peel of the “high priest,” serving in the most important role– the baking itself, putting the Matzos into the oven and removing them– such a toddler would be severely scolded.

But the most revered and desired role by all children was the role of the Redlen – the piercing. That is a role which requires a great deal of training, agility and special talent. But how could you acquire practice when you are not permitted to the “Holy of Holies,” the table of the Redlen, and not be given a chance to test your strength?! And if you did get a break and you finally get the privilege of trying, when the tired piercer feels kind enough to hand you the docker, you need to prove your agility and produce a properly pierced Matzah, worthy of entering the oven and coming out with no blisters and not swollen. And if, God forbid, you failed your task– then the baker would give you a taste of his bread peel, and would shamefully throw you out of the “Holy of Holies” with oaths and curses, to the laughter of the professional piercers. The man who was especially dreaded by those who gave the piercing task a try was Moshe David Dimenstein, God rest his soul. And I remember well the feeling of the long bread peel coming down on my shoulder after my numerous efforts, mostly ending with failure. How happy would be the boy who would overcome the hardships and the suffering after many failures – to produce a properly pierced Matzah. After that he would win the title of “Redler” and could come into the “congregation of God,” to be one of the experienced and seniors of the profession. With enthusiasm and great devotion, the happy boy would replace the payed professionals and work for hours next to the table as a resident, who would even be recognized by Moshe David as a professional who was qualified by him – and not by the long peel but by a compliment. Indeed, it was doubtful if there would be a happier man on that day in the entire world.

The baked Matzos would be piled in tall baskets padded with pure white and ironed sheets, and after the quota baked for someone would be filled, the basket would be carried by hand to the house, with the children of the family happily escorting the procession.

And in the houses, in those days, there would be great commotion toward the holiday. After the cold had passed and the spring with its warmth had melted the frost on the windows, the double–glazed windows would be removed and carried to the attic. The cleaning work would commence, thoroughly scrubbing the entire house, every room and every corner. All the portable furniture would be taken out, all the walls painted white, the furniture cleaned outside with warm water, the windows washed – to sum it up: everything was cleansed and polished, as if to welcome a respectable and important guest. The children would run around, couldn't find a place to settle in and would be a nuisance for the adults. When they would appear in one place they would be driven out only to appear somewhere else, to be driven out from there as well.

And when the task of sweeping and cleaning would be over, the furniture would be taken back in and the Passover cutlery would be brought down from the attic; these would be taken for Hagalah, purifying them by immersing them in water. Knives and forks would be tied on a long rope to form a long chain; along with the other dishes they would be taken to the river, that had lately been freed from the shackles of ice, and were dipped in it. The children who were permitted to place the cutlery as part of the Hagalah would be delighted. The ritual of the Hagalah would take place in the public bathhouse where the cutlery would be dipped in boiling water. I fondly watched the plates and saucers, which had golden or silver rims and the cups adorned with golden lines and lovely drawings. What special warmth would fill the heart in sight of these! But one would not get enough of these sights and immediately would be called to the pestle for the grinding of the Matzos. This wooden tool with a deep recess was meant for receiving the crispy Matzos, and a big wooden mortar would be used to crush the Matzos and turn them into flour or flakes for soup. This task was prized by the children who did it, but they soon grew tired of it because of the great effort it required.

And the last day before the holiday had arrived: the eve of Passover – “Put thy shoes from off thy feet.” On the evening before, they would start the ritual of Beur Chametz, the burning of the leaven. Earlier, crumbs of leaven would be scattered in various places in the house, and then the father would walk around, carrying a candle, “searching” for them and finding them, cleaning well the places where the leaven had been “found” with a rag. On the next day, a sale of the leaven would be held at the Rabbi's house. On that day, yellow sand would be spread on the floor, white tablecloths would be put on the tables, and very special care would be given, so that not a bit of leaven would be found lest the Passover would be damaged. And since the bread had completely vanished from the house and it is still forbidden to eat the Matzah, we ate a lot of potatoes – a “neutral” food kosher for Passover. Everyone would rush to the bathhouse to wash themselves in the boiling water and to go and sit up on the sweating benches, where the steam would rise from the stove in front of which would be hot stones that had streams of hot water poured on them. Above the top bench came the voices of Jews enjoying the choking heat and the whipping of brooms being brought down on their hot bodies. I especially remember the one who was the bravest in lying up on the top bench, a place where only few would be able to hold on – Yenkel Yanovski, who would growl “ay, oh oh”– in mixed pain and pleasure. Washed and cleansed the respectable heads of families, with their children, would emerge from the bathhouse, and rush home for the final potato meal before the Seder and hurry to the synagogue.

And how great was the light in the synagogue that was also cleaned and prepared for this festive evening! Many lights were lit in honor of the holiday, including the gas lamp, which Shaya–Yosef had skillfully taken care of a long time before sundown, a skill which only he possessed. Light and the joy of holiday was all around. The holiday prayer would be happily recited and with an elated air, with everyone filled with self–importance, mixed with a feeling of a bit of Jewish pride. After the end of prayer, they would greet each other with “Gut yomtov” – “Happy holiday”– and would march home with their families to the tables laden for the Seder.

The pillows to recline on for the father on the bench is next to the head of the table, the bowl in the center, everything in accordance with the custom. Out of all the houses, the shrill voices of the children of Israel would be heard, asking the Four Kushiyot – the four questions – “Ma nishtana ha'layla haze mikol ha'leylot?” – “How is this night different from all nights?” and after the questions would come the answers with the traditional melody: “We were slaves to Pharaoh in Egypt.” The first cup and then again Haggadah, and more Haggadah up to the washing of the hands – and then the festive feast would commence in every house, even in the houses of the poor, who would not be forgotten, since the able would remember the Mitzvah of “Kamcha Depascha.” The Kneidlach, the matzo balls, and the Chremslach, the small fritters filled with goose fat practically melting in the mouth, and the delicious chicken soup. The doors would be opened for the saying of “Shefoch chamatcha el ha'goyim” – “Pour out thy wrath on the gentiles.” Again, the Haggadah. The song of “Chad Gadya” comes out of every house. The children await the coming of the prophet Eliyahu, but fall asleep and are carried one by one to their beds. Only the head of the family and the grownups go on reading the final chapters of the Haggadah, with their eyes slowly closing. Hush, everything is silent. The town is asleep, with only the dogs barking in the yards of the Goyim breaking the silence of night and holiday. But the peace in the Jewish heart is encouraged and strengthened, because he will remember the verse “U'livey Israel lo yecheratz kelev leshono” – “And unto the people of Israel even a dog would not move its tongue.”

On the next day, the housewives would rise early to prepare the dishes for lunch. The young ones also would get up to receive their share of nuts, nuts from Turkey and local nuts, as well as big nuts called “Veleshe Nis.” Right after breakfast they would rush to meet their friends and play the game of nuts. A plank would be set against a wall, for rolling down the nuts. The nut hitting another on the floor would be awarded to its owner who collected both and the game would go on. Those who would be lucky would fill up their pockets, and those unlucky would have empty pockets, and they would shamefully return home and beg their mothers to get another share. Others played the game of “odds and evens,” with their closed palms holding the nuts, so that their amount wouldn't show. Fights would sometimes start as well, often with children playing, and might even turn into scuffles.

Passover in town: there would be no days like the days of Passover with light and celebration, because along with the celebration of the heart, nature would awaken all around, showing its signs in everything – the rejuvenation of nature and Jewish person alike.

Shavuot

And from Passover to Shavuot. The hot days of summer, the days of the Counting of the Omer, and only one day, Lag Ba'omer, is to remind us that not everything is secular in the world. But that day would go by almost unnoticed in town, apart from the children in the Cheder who would make themselves bows and arrows and would roam the field and forest.

At a certain distance from Lag Ba'omer, the holiday of Shavuot would wink, the holiday of Matan Torah – the giving of the Torah. And dairy foods: “Blintzes,” cheese–filled dumplings. The floor of the house would be covered with yellow sand; greens for Shavuot bring the memory of the Bikkurim, the first fruit. The holiday prayer in the illuminated synagogue and the holiday rest – that is the holiday of Shavuot as I have it imprinted in my memory. The holiday did leave a deep impression on the children.

After Shavuot, the scorching days of summer would begin. The children would taste of everything to the fullest. Bathing in the river, picking and stealing fruit, carrying off fruit from wagons and shops of the peasants, going afar to the pea fields to fill up pockets with pea pods and even the inside of the shirt up to the chest. These trips had many dangers involved since the unlucky boy who would be caught stealing would have his hat taken away and even his shirt sometimes. And a group who would be chased by the Goy who owned the field or the orchard with his dogs – woe to them – but it would be worth the risk, worth the labor and trouble, since “stolen water would be sweeter.”

Tisha B'Av

And days of grief and mourning are in town – the first nine days of the month of Av, the memory of the destruction of the temple. On the night of Tisha B'Av in the synagogue, the adults sit with their shoes off, sitting on overturned, low benches, and the cantor chants the lament of “Eicha” in a sad melody, but the children do not know the grief of destruction. In a day, their pockets will be filled with the cones of a thorny plant call “shsishkes,” and while the laments are sung they will send the cones in clusters or one by one, into the thick beards of the mourners over the fate of Jerusalem. Among the ones taking the shots there would be those who accept the arrows shot at them with indifference and understanding, sometimes with love. And then there would be the ones who get angry, reacting severely and looking for the mischievous brats who attack their beards. The latter ones are a more desired target than others for the mischief, and the atmosphere of Tisha B'Av, an atmosphere of lament of a crowd mourning the loss of what was precious to them, becomes an air of mischief, even happiness and glee, that would not settle with the solemnity of this day.

Celebration days

And the special celebration days in town were wedding days, but these had their scent and taste vanish during recent years, before the Holocaust. I'll bring the memory of the last weddings which kept the original tradition with all its grace and purity. I remember only a few weddings like that – two or three. And they lasted, I think, a few days, and no other days were like it in joy in town. I still remember a Chuppah in town that was held with all its practices and customs until the last of them. The entire town was gathered in the courtyard of the synagogue. Perl–Leah and Sheyne, the old women who knit socks for the members of town, danced at the head of the procession and clapped to the sound of a friendly, delightful and sad melody.

And how much light and joy was in the house where the wedding was held: “Die Kalah Bazetzn,” the groom coming to the bride sitting on a chair, the Klezmers playing, the crying of the women, the sounds of crying of the bride, in memory of the missing relatives. And later – “Die Chuppah Vetshere”– the wedding feast, “Sherele” dances and more.

And the next day again holiday and feast. The feasts would last whole days and on the Shabbat of the wedding week – “Sheva Brachot,” the seven blessings. But all these, as mentioned, were a way of being that faded away, with their shine dimming; only bits of memories stayed in my heart and even those are partially blurry.

“Bris Mila” – circumcision – that was also a celebration in a small circle in town. In the seven days before the Bris, we children would be invited to the house of the woman who just now gave birth to say certain Tehilim, to drive away the evil spirits. They would paste on the walls Tehilim of “Shir Ha'maalot” for that. The children would be treated with sweets in exchange for this service.

Death in the windows

And from joy to sorrow. A death in town; someone passed away. We young children would be terrified and forget our mischief for a moment. We were called to say Tehilim next to the dead person who would be lying on the floor with candles lit by his head. (Today I am amazed about our parents letting us stay in a house of mourners who had their dead lying in front of them.) The funeral proceeded slowly through the town's streets, the bed carried by the Chevrah Kadisha members. The charity box tinkled, the person carrying it called out loud “Tzedakah (charity) will rescue from death.” The wailing sound of the women, a heartbreaking sound, would pierce the silence of the crowd, walking after the bed.

Here the procession would reach the bridge on the river, and stopped for a moment to say farewell to the dead and ask for forgiveness. One by one the people escorting with their lips whispering “zeit mir muchel,” meaning “please pardon me, forgive me.” The bleak procession would pass through one of the Goyims' yard gate, since that was the only way to the cemetery. And when they would reach the gate of the cemetery and disappear among the trees, the crows' calls “Cra, Cra, Cra” would increase the sadness and pain of the heart. We children would be convinced that the crows would come to the cemetery with full awareness of the significance of the place and their calls were meant to express the pain of death and cessation. we would be comforted by the fact that the soul did not die and just went to heaven. But we would be divided in our views in the arguments we had – did it go to paradise or, God forbid, to hell, to be tormented in its seven sections, in tanks of boiling tar, or on burning embers or maybe on a white–hot iron floor.

I remember the air of death which would pervade town when one of its people would be terminally ill, when everyone would rush to the synagogue to say Tehilim, to add a name and to open the Ark. The wailing of the women of the family in front of the open Ark would terrify the town and would announce that death had risen in the windows.

We do not know what has become of that corner of town, the cemetery, the final stop of every human being, flesh and blood, when their time comes. But at the time it was a part of the everyday life of the town, and we didn't imagine, the few survivors, and definitely our brothers and sisters who were murdered in the Holocaust did not imagine, that even to this final stop the ones murdered would not arrive, that their bones would be scattered all around to be fed to wild beasts, and will not be visited by their children, their brothers or their sisters to come to their graves, to commune with their memory, to say the Kadish prayer in memory of their souls.

|

|

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Narach (Kobylnik), Belarus

Narach (Kobylnik), Belarus

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 27 Jan 2018 by LA