|

|

|

[Page 147]

New Breezes

The spirit of progress and tolerance slowly penetrated into our region as well, and brought about a change in traditional education. When the walls of the ghetto collapsed, it became apparent that Jews were capable of attaining the heights of European education.

Khone Rays, a Jew from Khotyn, was a true personality, who fought successfully for education and progressive thought. Without entering into a conflict with the opponents of modern education, he founded two cultural institutions in order to stimulate the younger generation: “The Club”, and the Talmud–Toyre. The adherents of traditional education feared that modern education would estrange the young folks from Jewish tradition and lead to assimilation. However, Khone Rays was not fearful, because he himself was rooted and anchored in Jewish tradition. He worked to weave together, in a original fashion, traditional Jewishness and the new reality. He tried to show that modern education and Torah could live under the same roof, and one would not disturb the other, regardless of the great differences between them. During his trips to faraway places he saw the changes that had occurred, changes that were another cause of the decline in Jewish values.

Khone Rays devoted his energies to the young, and saw to it that poor children would also gain an education. He brought in good teachers, and organized a choir in the “Club” as well as an orchestra, so that young people could learn music. He was also concerned with physical education, and bought equipment for gymnastics. He instituted uniforms for the athletes so that there should be no difference between rich and poor. A library was set up in the school, to which young and old alike came.

It can be said that the doubters feared in vain; there was no estrangement or alienation from traditional and national Jewishness.

The Tarbut School

The Zionists originally opened the Tarbut school in Yehoshua Vaynshtok's old building.[1] The first teachers were Zalman Malamud, Vaynshtok, Leyb–Dovid Stoliar, Lam, Nisim Krivoy, who were later joined by Khave Zaydler. At first, it was a kheyder–metukan.[2] In 1922–1923 the school moved to the center of town, and that same year it was officially recognized by the Romanian authorities. The permit needed to be renewed annually. The school was supervised by the Kishinev central bureau and the commission appointed by the Romanian Ministry of Education.[3] The Tarbut school was almost the only one that required tuition payment. The school also

[Page 148]

received donations, thanks to various evening events that were organized, as well as from the Jewish community. The members of the school committee were Y. Apelboym (President). M. Axelrod, A. Berg, Berl Vaysodler, A. Zaltzman, Mordechai Telemus, I. M. Tisenboym, and Hirsch Feferman. Hebrew was the dominant language in the school. Jewish history and national consciousness were the core of the curriculum. On the other hand, care was taken to follow the government curriculum. Khave Zaydler was the official director as far as the authorities were concerned, and she was responsible for all the general studies. Zalmen Malamud was the actual director of the school and was responsible for all the Jewish studies.

Tarbut schools were opened in most Bessarabian towns. The central bureau was in Kishinev, headed by Attorney Shmuel Rozenhaupt. Representatives of the central bureau visited from time to time and showed interest in the progress of Jewish studies. The central bureau was also in charge of obtaining the proper permit from Bucharest.

The Tarbut school

The Tarbut school building also housed the synagogue attended by the Zionists as well as a school, a library, and a hall for conferences and meetings. The building was owned by the Tutelman brothers, and they received the rent. In 1935–1936, the brothers decided to sell the building, but the Zionists were reluctant to buy it. First, they did not have the money needed; second, there were already rumors that Bessarabia would soon be annexed to the U.S.S.R., and that the whole project was not worthwhile. Actually, some argued that even if it was taken over by the Russians, the building could be turned into a folk cultural center for the entire city.

The Russians arrived in 1940, and turned the Tarbut school building into a military command center. A fence was erected around the building and the former owners did not even dare to approach. The biblical curse “You shall build a house and not live in it” came true…[4]

Sholem Shrayer

Sholem Shrayer was known in Khotyn as a teacher in the “Club” Talmud–Toyre that was established by Khone Rays. Sholem had a special gift for music and was active in the school orchestra. His wife, Esther, was renowned as a teacher in the girls' school. She wrote her own songs for theschool holiday celebrations. Sholem Shrayer was involved in starting the self–defense organization, where he was one of the instructors. He taught the children languages, music, and gymnastics. For years, he was the manager of the bes–medresh in the courtyard of the great synagogue.

Dovid–Leyb Kuperman

Dovid–Leyb, son of Yankev–Fishl the ritual slaughterer, was born in 1899 and was killed in Ukraine by Nazi bombs in 1941. He was a gentle soul, a scholar, and an educator with broad horizons in worldly matters. He was constantly studying and doing research. He edited a Mishna for beginners, with explanations of difficult words, and compiled study books for beginners. Unfortunately, he did not have the money to print these books. Kuperman held an honored position among the teachers of the town. He himself taught Hebrew in the “Club” school and raised a generation of Hebrew speakers and readers. Kuperman was a lifelong Zionist, but never held official positions. He was constantly concerned with educating children in the spirit of Torah, social responsibility, and aliyah.

melameds and kheyders

The melameds were usually not prepared to be teachers, and teaching was not their profession. It was usually a solution for people who could not make a living and could no longer be supported by their fathers–in–law.[5] They opened a kheyder in order to support their families. A small number of melameds understood how to make contact with the children and thus could fulfil their role as teachers. An unprepared melamed had an adverse effect on the childrens' education and on everything concerning Torah and Jewish tradition.

Let us mention a few of the melameds in Khotyn.

Hillelke (Reb Shloyme Tsemakh) taught the youngest children. His kheyder was in a large room in his home; his wife cooked and ran the household in the same room.

[Page 149]

Shmelke, the son of Aaron the mohel, was a devoted follower of the Czortkow hasidic group. He was known in Khotyn as a teacher, scholar, who knew the sacred and secret texts. He had previously been a trustee of the Rays family's forests. However, as he had small children to take care of, he became a melamed; this increased his income.

Yankev–Yosef melamed was a Husyatin hasid. He was quite a figure, and was loved by many. He was careful to assemble students of similar intellectual capacity in the same class. He would also organize study competitions between classes. The writer Ya'akov Fichman was one of his students.[6] Reb Yisroel Lerner, who was called Yisroelke Rov. He was the son–in–law of the rabbi, Reb Khayim Roizman. He came from Podolia, and was considered one of the best teachers, who prepared students for ordination as rabbis; he also wrote a number of articles.

Avrom, the son of Shmuel–Layb Shrayer, opened, along with Note Michnik, a small yeshiva for Talmud study. Among his students were the sons of the Hasidic leader Rabbi Twersky; some of his students were later accepted into the yeshiva of Lublin.[7] En route to Transnistria, a non–Jew pushed him out of the railway car.[8] When he ran after the car to save his tallis and tefillin , a soldier shot him; he remained lying in the road and was never even buried in a Jewish cemetery.

Reb Nissele Posek prepared students for rabbinical ordination. He had few students, and was very strict about their everyday habits. He educated three generations of students.

Teachers and Educators

Khotyn had several teachers who participated in the modern education that was introduced. Each had his own distinct way of teaching, as there was still no generally accepted method. Each, however, considered his profession to be a mission for improving society and not just a means of earning a living. Among the teachers were writers and social activists.

D. Fradkin came from Lithuania. He was an active member of the Mizrachi movement, who knew Hebrew and Russian perfectly and was a poet.[9]

Khayim–Hersh Vaynshteyn (the Shotov melamed) taught using the new method known as “Hebrew–in–Hebrew.” In the course of one year his students became able to use the language in everyday life. On Shabbes they would visit him at home, and discuss books. Each student would give a report, in Hebrew, on a book that he had just read; this enriched the entire group in both general knowledge and language proficiency. Vaynshteyn had to flee from Khotyn in 1910, as he was wanted by the police.

Other teachers were Shabtai Lerner, who taught Russian and Hebrew; Tsila

|

|

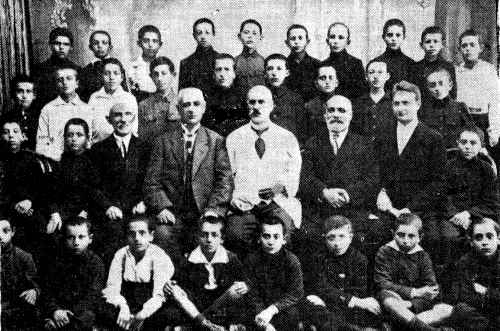

| A class in the Talmud–Toyre school (“Club”) |

[Page 150]

Lerner, director of a special school for refugee children who had been driven out of the villages in 1914; Itta Geller, the daughter of Zalmen Shoychet; Aaron Vaysberg, who left for Iasi in 1919 with the help of Mikhoel Landau, and served for a long time as leader of the Maccabi sports organization of Romania; Gedalya Shrayber (Lipiner), who opened a library in the school; Yoel Prokuror, a Yiddish teacher; Azri'el Yanover, a Yiddish teacher in the school for refugees (Bzhenski school), who was also a poet; Sonya Barag; Sonya Laybman.

|

|

| The Talmud–Toyre school |

There were also two government middle schools (gymnaziyas ) in town, one for boys and one for girls. Students had to attend the government school on Shabbes as well. There was only one Jewish teacher in the government schools, though Jews constituted one–third of the population.

Reb Yechiel Kretshmer

Naturally, time cloaks memories in a special light and causes faults to be forgotten. However, there were figures that were enveloped in a special light even when Khotyn was still a Jewish town. One of these was certainly Reb Yechiel Kretshmer, teacher and rabbi, and an honest man. He also worked in the town offices. Reb Yechiel had had a difficult childhood, as he was born into a poor family. He achieved everything under his own power. Even when his vision suddenly weakened, he did not stop teaching, thanks to his memory. Even when blind, he distributed his spiritual treasures. His love strengthened thanks to the Torah, which safeguarded and supported him. Reb Yechiel restored to Jewish tradition those young people who were enticed into alien ideologies. But even those who strayed from Jewish practice certainly remembered, in moments of despair, the sweet phrases they had heard from Reb Yechiel, phrases about the Jewish spirit. Those memories were sure to console them.

Yoel Prokuror

Yoel Shnayderzon, known in Khotyn by the nickname “Yoel Prokuror” was only a private tutor. He attained the status of teacher in a school only later, in Czernowitz. Yoel melamed barely made a living, but he and his wife were generous toward all. They especially loved young people; young folks visited Yoel's house day and night. Non–Jewish youngsters would also come and sing Yiddish songs along with our young folks. One of these, Shilin, was an attorney who later became a prefect in Khotyn. Because of these youth gatherings, law enforcement kept an eye on Yoel's house, and the police actually came more than once to sniff around and search.

[Page 151]

The young folks did not only talk and sing, but also ate and drank everything that was available in the house–naturally, at Yoel's expense. And when Hirsh–Ber Ayzenberg needed to be released from prison, Yoel Prokuror pawned his polecat fur coat and freed the young man.

Sometime in the 1930s, Yoel left for Czernowitz, where his luck changed for the better. Not only did he make a good living as a teacher in a real school; he was also called “Professor.” Actually, he never really felt at home in Czernowitz. He was lonely, and the title of Professor did not warm his heart. When he longed for some familiar warmth, he would drop in in Khotyn and spend time with his old friends.

Yisroel Goikhberg–Teacher and Poet

Yisroel Goikhberg was a remarkable teacher, who always turned the school into a temple, even when he had to teach in a cellar. Circumstances almost always set him in poor localities. He was a teacher for many years in Brownsville and Williamsburg. However, anyone who came into his class felt that he was entering a place of holiness. Yisroel Goikhberg was blessed with talent: he wrote poetry, sang well, painted, and was a theater director. Goikhberg considered teaching a kind of national mission, an act of worship. Thanks to his educational gifts, he had great influence over young people, as well as on adults. Students loved him, because they could sense his directness and intelligence. Thanks to his teaching method, the students became used to speaking and reading Yiddish. He would personally choose reading materials for them, based on each student's experience. Whenever he organized a celebration in the school, he made sure that the occasion found expression in art, written work, and in the atmosphere as a whole.

Goikhberg was a poet with a profound musical sense, probably because he came from a family of cantors. He wrote didactic poetry, typical of a teacher who knows exactly what he wants to say and expresses it clearly, without hints or symbols. His poems need no explication. He wrote for children and young people, However, he didn't want to be considered a writer only for the young –and he was right. Yisroel Goikhberg left behind a rich spiritual legacy: Songs of Our Generation – poems about the great American city of Boston, where he settled after coming to the U.S. in 1913. Boston was also where he started to work as a teacher. Let us also mention the childrens' poems Good Morning and the verse narrative Kamtza and Bar–Kamtza; the poetry volumes Verticals and Nemirov–A Chronicle in Verse. Goikhberg's last two books, With All My Might and With a Smile were published in Tel Aviv by Peretz Farlag in 1963.

Yisroel Goikhberg had a thorough Jewish and general education. At first he studied in Khotyn's kheyder metukan, and later graduated from a middle school

|

|

| The Bzhenski school |

[Page 152]

in Kamenetz–Podolsk. In 1917–1921 he studied in Iowa and became an engineer. His late book With All My Might actually includes many poems of intimate familial character, but their poetic content is meaningful to every reader. Some of his poems were turned into folk–songs, with the author of the lyrics unknown. Goikhberg recounted how, on a visit to Israel, he visited a school during a singing class. The children sang Goikhberg's poem “Three Boys,” but the teacher did not know who had written the lyrics. He was astonished to hear that the writer was Goikhberg himself. Many composers wrote music to Goikhberg's words. Many of his childrens' poems were influenced and inspired by his own children. He used simple words to make the poems accessible to children. His poems were included in all school readers. In 1948 a volume of childrens' poems appeared, titled The Golden Peacock; the book, which included texts and music, was edited by Yisroel Goikhberg. The first poem in the book is dedicated to the pioneers of Palestine; it was recited in all the schools and was also included in modern Passover haggadas.

For over 45 years, Yisroel Goikhberg was President of the Pedagogy Committee of the Sholem–Aleichem schools, where he developed curricula, edited childrens' magazines, and was a gifted teacher. Goikhberg died at age 76.

Leyb–Dovid, son of Reb Nachman Stolyar

People called him Leybele Stolyar, because everyone who knew him – family, friends, and acquaintances – loved him for his good qualities.[10] He was a both a scholar and a fine, kind–hearted person. He was born in Zwanice, Podolia, where there was strong interest in the ideals of a return to Zion and the revival of Hebrew. The younger generation grew up in this atmosphere, Leybele Stolyar among them. He was influenced by an ardent Zionist, the teacher Sholem Altman, may his memory be for a blessing.[11] After Leybele finished school, his pious father sent him to the yeshiva of Kamenetz–Podolsk. There, he learned – besides Talmud – modern Hebrew and grammar, as well as modern Hebrew literature.

In 1914 he settled with his family in Khotyn. Leyb became a teacher in the Tarbut school, and gained the affection of the children as well as of their parents. He married Nesia Shuster, and moved to Dondushen, where he continued to work as a teacher.[12] In 1934, he moved to Colombia with his wife, where he worked hard to make a living. On the other hand, he took on groups of adults and taught them Hebrew free of charge. He later moved to Israel, but became ill shortly afterwards and died on May 27, 1965.

Khotyn Men of Letters

It is worth mentioning the following men of letters in Khotyn, who produced poetry and prose as well as religious literature.

Rabbi Shoulikl wrote a commentary on the Talmudic tractates Bava Metsia and Bava Kama, and an unfinished commentary on Bava Batra.

Shloyme Shkolnik was a teacher in the Talmud–Toyre who wrote a commentary on Psalms. He came from a family of cantors and wrote his own cantorial compositions.

Sholem Shrayer published a book in Khotyn titled Different Aspects of the Intersession (1893). He describes the difficulties of melameds seeking new students.[13]

Shabtai Lerner (1879–1913) spent his childhood in Balti.[14] He taught Hebrew and Russian and also wrote folksongs, to which he composed music. He wrote plays and was an actor himself. In addition, he translated poems from German and from Russian. Let us mention his works “In a Foreign Place” and “The Jewish Knapsack.” He died of tuberculosis.

Azriel Yanover (1875–1938) came to Khotyn in 1895 as a teacher. He wrote a play (“The Thwarted Love–Affair”) that was produced in Khotyn, and worked in the Undzer Tsayt newspaper.

Simcha Malamud of Khotyn published a book titled Poems and Tales in 1923. He was a member of the American Workmens' Circle.[15]

Heynekh Akerman was born in 1901 in Malenice, near Khotyn.[16] His first poem was published in Der Morgn, which was published in Kishinev.

[Page 153]

He left for America in 1920, where he printed his poems in many Yiddish publications. He also published articles under the pseudonym “A Man from Malenice.” Together with Moyshe Shtarkman and Zelig Dorfman, he published the collection Reflections in April 1932.

Eliyohu Lipiner was born in Khotyn, lived in Brazil for many years, and later settled in Israel. His work encompassed two areas: Jewish history during the Spanish Inquisition, based on previously unknown documents that he found in the Inquisition's archives; and the history of the Jewish alphabet. Among his works are the books By the Waters of Portugal (YIVO 1949); The Ideology of the Jewish Alphabet (YIVO 1967); essays in Portuguese periodicals and in Di Goldene Keyt; Between Marranism and Apostasy (Peretz Farlag 1973).

Gershon Kirszhner was born in Khotyn in 1894 and stayed in the U.S.S.R. In 1935, he published a volume of poetry titled Today and Tomorrow, in Czernowitz.

Moyshe Gitsis was born in Khotyn in 1894 and went to the U.S. in 1909. He later returned, and served in the military in World War One. He went to the U.S. again in 1922. He was a writer, actor, and theatrical director. His works are: “Bells” (drama), 1926; Stories (1932); The Sun in the East (1936);

The Orchestra

As it happened, luck was on Khotyn's side during the difficult years of 1904–1905. At that time, a number of young physicians, attorneys, and chemists returned from the U.S., and contributed to the social revival of the town. They also attracted other people to their cultural activity. Mendel Rays, one of the richest men in town, had several sons, who almost all became bankers like their father, except for one, Khone Rays. He was not suited to banking or to commerce. Khone divorced his wife and

|

|

| The orchestra The children with Khone Rays, Shloyme Shkolnik, Khayim Vaserman, Sholem Shrayer, and Friedman, the music teacher |

[Page 154]

devoted himself completely to community work. He would go to Germany and Austria every year and return with new plans for the Club that he had created in Khotyn.

Khone Rays established a wind orchestra that attracted everyone, just like the bes–medresh of old. The orchestra was established in 1904, and reorganized in 1910. Its 45 members played voluntarily.

Khone Rays brought instruments from Leipzig, and a conductor from Kiev who was a talented musician. The orchestra became famous; when the Tsar came to Kamenetz–Podolsk in 1915 the Khotyn musicians were sent to perform for him.

The orchestra gave concerts four times a week and attracted many young people. It could be considered one of the best orchestras in Bessarabia. Its professional level may be attested in the remarks of General Drexler, the Director of the Saratov Conservatory, who was then the President of the Russian Red Cross. He was in Khotyn during World War One, and was greatly impressed by the orchestra. The general promised that the Club musicians would receive scholarships to the Saratov Conservatory; however, conditions prevented these promises from being carried out. After the war, he left Russia and worked as a waiter in Berlin.

Many Jews survived World War One thanks to this orchestra. A general came to Khotyn and demanded a list of all the musicians in town in order to mobilize them for his division. A list was made of as many young people as possible, in order to save them from battle. Among them were some who had never held an instrument. The general took them all, and they returned home safe and sound two years later.

Theater in Khotyn

In 1909–1910, Khotyn was fortunate enough to have an amateur theater, directed by Binyomin Khalfon, Yosl Geyman, and A. Babitsh from Zwanice. Over two consecutive years they mounted several performances, with success. Among the productions were two of Avrom Goldfaden's operettas, “Shulamis” and “Bar–Kochba.” The major roles were played by Sonya Gitsis, the wife of Yisroel Kharif. In spite of its great success, the ensemble existed for no more than two years. After a long hiatus, a young people's amateur theater troupe was created; Moyshe Gitsis and Avner Barak maintained it until 1930. They put on productions of work by Yaakov Gordin, Peretz Hirshbein, Sholem Aleichem (“Dispersed and Scattered”), and others. Avner Barak and Manya Zeldman were especially noteworthy actors. The income was dedicated to the Jewish Library. Occasionally, the “rebels” tried to produce shows that suited their ideas; however, they succeeded only once.[17]

Long before World War Two, the left–wing Kultur–Lige started a theatrical group; the ensemble of about 20–30 actors was directed by Yankl Barak. The authorities constantly suspected the actors of being communists and persecuted them ceaselessly. This was why they were unable to develop a regular program.

|

|

| The dramatic society of Khotyn, “Art and Life,” honors our member, Miriam Zeldman, as a serious and devoted actor on the Yiddish stage,

who has for almost five years ceaselessly worked for the society, and even more – for the poor, the sick, schools, etc.

The members of “Art and Life” request Miriam Zeldman to accept this worthless present, and swear that the image of our dear and beloved Miriam will always remain deep in our hearts.

|

[Page 155]

The frequent arrests of actors caused interruptions and upsets. The actors included Sonya Grinberg, Esterke Grinberg, and Roza Gitsis. Reb Yisroel Kharif, the father of Roza Gitsis, was very displeased with his daughter's friends. He ordered her to cease the activity.

Yisroel Gitsis, whom people called Reb Yisroel Kharif, wholeheartedly supported theatrical activity in Khotyn. He had inherited a grand house, which was always open to Jews and Christians alike. Lumber merchants, officials, and good friends would visit. The Rebbe of Czortkow would stay with him when visiting Khotyn. Yisroel Gitsis himself was the manager of the great synagogue. His wife, Sonya, was also renowned for her acting in the dramatic club as a prima donna in Goldfaden's operettas. Their son, Moyshe Gitsis, wrote plays, and organized and directed performances. The daughter, Roza Gitsis, was linked with the Kultur–Lige, where she distinguished herself by her singing, acting, and dancing.

In those years Khotyn started to look outward to the world and to follow events. High–school and college students organized clubs and set up literary evenings, recitations, singing and dramatic performances. The initiative was that of Moyshe Gitsis and his friend Itsik Getiya. They ran the recitations and prepared performances in Russian. These events were very successful. World War One interrupted this activity, but after a while we grew closer to the dramatic clubs that performed in Yiddish. There we became acquainted with the very talented Avner Barak and with Yisroel Barak, our regular prompter. We should also mention the wonderful actress Rivke Tikelman Kudrinietzky.

The Yiddish performances were very successful in summer theaters. The Khotyn audience was always extremely interested in our programs and hurried to buy theater tickets. This continued until 1920, when I left Khotyn, and the stage. This was the end of my connection with the Khotyn theater. But my experience in Khotyn was a good education for later years, when I began acting in Chicago.

The Zionist organizations also had their dramatic clubs. Some of the members worthy of mention were Engineer Yoysef Zeltzer, Berl Visodler, Leyzer Vayzer, Fishl Gitelman, Hirsh Vaysman, Yente Kriszhner, and the actor and director Nahumovitch. The income served to help the poor.

The “Shnayderman” hall

The old “Shnayderman” hall, known for a long time as the hall of Yoyne Zilberman, was the cultural and artistic center of Khotyn. Its stage was the scene of the performances of the greatest actors of the Jewish –and non–Jewish–theater. It was also the place where Zionist leaders held lectures. Political meetings took place there as well as literary evenings, symposiums, and Khanike and Purim celebrations. It was used as a the Khotyn summer theater until late in autumn. The hall was in the middle of town, surrounded by a beautiful garden and trees. The Jews of Khotyn would fill the hall at every chance. They loved theater, loved to hear a good speaker, and would come to Zionist meetings (which, by the way, often ended in blows). When the rains began, the hall was no longer comfortable: it was cold and wet, and the entrance was slippery. Nevertheless, we liked the hall. It was ours, our theater. People waited impatiently to hear Poyme Treger announce the evening's program on the street. Boys would wait until nightfall and hide in the trees around the hall, where they trembled and waited. When the performance was about to start, the gang would jump over the tall fence and sneak into the hall. However, this was not so simple. The plan did not always work; the adventure often ended in torn pants and a scratched face. But it was worth it in order to go to the theater without buying a ticket. Other theater–lovers waited at the entrance until just before the beginning. They would then start negotiating with the theater owners for cheaper tickets. Here and there someone would grab a broken chair, just as if he were “a member of the troupe.”

[Page 156]

We were proud of the Shnayderman hall, with its muddy floor and all its drawbacks. That was the scene of our cultural life during the period between the world wars. We were then cut off from the Russian world and had not yet connected with the Romanian regime that had begun to rule Bessarabia. Anti–Semitism, however, came at us from both sides: from the local Ukrainians and the Romanian newcomers.

The Khone Rays Library

A library named for its initiator, the cultural activist Khone Rays, was opened in the bank building. Rays's private library was a good foundation for the library, due to the great number of worthwhile books it contained. This legacy from Khone Rays developed into a proper library, which included a reading room. Clerks from the bank worked as volunteers in the library. The library committee was headed by Miron Derzhy; the librarian was Etka Shitnovitzer (Shmidt). Eventually another librarian, Milya Barak (an attorney) joined in. Young people and students were very helpful to the library's everyday operation. The library had 500 regular readers; about 120 readers came daily to exchange books. The library attracted many young readers thanks to its large collection of classic literature, especially in Russian. The library contained books in Yiddish, Hebrew, Romanian, and Russian. The many Christian readers also found everything they wanted. Books would be ordered from Warsaw, Riga, and other locations. The reading room was always full, as people read all the newspapers and periodicals. The library was a cultural center, a meeting place for intellectuals and young people. This was the case until the Soviets took over Bessarabia.

Yehuda–Khone Axelrod

Yehuda–Khone Axelrod was one of the finest young men of his time. He did not want to make a living by teaching Torah, and worked as a bookkeeper for various factories. He made sure that the workers would be paid on time and would not be wronged. This endeared him to all. He usually interceded wherever there was a conflict, and made peace. Everyone knew him and considered him an unusual person who loved justice. He was never able to earn a living that was sufficient for his household and eight children, but he was always satisfied with his lot and took everything in good spirits. His children inherited all these positive traits. Yehuda–Khone was one of the founders of the Tarbut school, which was the pride of the Jews in Khotyn and brought great benefits to the Jewish population.

Zalmen Malamud

He was certainly one of the outstanding figures in the cultural and educational field in Khotyn. He did much for the Tarbut school, where he introduced modern Hebrew. In addition, he organized Hebrew classes – in the morning as well as the afternoon – for the Jewish students in the government schools. He had a pedagogical approach to the children and took each one's personality into account. Even when he was not the director of the Tarbut school, the town considered him the school's spiritual leader. He understood how to mesh study of the sacred texts with everyday subjects by removing the artificial separation between them. He himself was pious and often led the community prayers and read the Torah for the community. He was active for the Jewish National Fund, and the secretary of the local branch of Mizrachi.

He had a deep longing for the Land of Israel, but did not have the chance to settle there. He died in 1941 in the Sekiryany camp, alone and abandoned. No one accompanied him on his last road.

Khayim Vaserman

Khayim, the son of Yaakov Vaserman, was born in Khotyn in 1877 and was well known as a teacher and the director of the Club school. He made a living by tutoring. He opened an elementary school and later a teacher–training college in the town. Khayim Vaserman worked as a teacher for over 40 years, until the Nazis and their helpers killed him during the Khotyn massacre of July 9, 1941; he was 64 years old.

[Page 157]

|

Gedalyahu Lipiner

| A Star

I look through the window and see a star–

A plot of muddy soil, cold souls,

Truth and honesty

Wisdom and education

The star understands my thought

If you could colonize me

You'd stuff yourself

Your mind would be free to think,

Stay well, o miserable child,

Stay comforted, oh, stay comforted |

[Page 158]

Gedalyahu Lipiner

| The Fable and the Writer

“You, my fable, go around the world

“You send me, writer, on a fool's errand,” |

| The Atonement and the Sinner

It's ancient Jewish custom, the day before Yom Kippur, |

| The Dog and the Pig

Once a dog attacked a pig

“You dog, I will stop being a pig,” |

[Page 159]

|

Mendl Nerman

| Poems of Sunset and Autumn

a.

The day shuts its tired eyes

The goblet touches someone's lips,

Life is a guest to some, b.

I sought out a land

The sun set over there

The land has no king,

And in that dead land

The morning sun rises there c.

The day lies, half–dead, on the bier

Autumn roams the forest along with the sunset

Dirt roads lie red in the twilight, with bloody sand |

[Page 160]

|

Meir Kuchinsky

The Philosophy of the Hebrew Alphabet

The Ideology of the Hebrew Alphabet by Elyohu Lipiner, YIVO Argentina, Buenos Aires 1967. 600 pp.

The encyclopedic work The Ideology of the Hebrew Alphabet, is Eliyohu Lipiner's third book. The first, Letters Recount, was published about 25 years ago. The second, By the Waters of Portugal, which received the Lamed Award, also published by the Argentina YIVO, appeared eighteen years ago. In the years between books, Lipiner published very important and original essays on historical themes, in the most highly regarded Yiddish and Portuguese periodicals. Artistically, these articles were truly fine belles–lettres based on chronicles that Lipiner discovered and put in context. In other words, materials that would have remained dry chronicles in the hands of other historians were turned by Lipiner into sparkling descriptions of life, with all the dramatic, painful, and often romantic developments. However, they were always true to historical facts.

A few years ago, he succeeded in gaining access to the Inquisition archives in Lisbon. This diligent scholar, so well–versed in ancient Portuguese as well as being a jurist, is familiar with the clever and twisted manipulations of that evil tribunal, brought back an enormous amount of material. Since then, his scholarly research has concentrated on the Spanish–Portuguese period of Jewish martyrology and the martyrdom of the Spanish exiles, the Marranos, and the Inquisition (which was translocated to new centers in the Americas), He was able to decipher a number of personal tragedies resulting from numerous Inquisition trials; only now, 400 years after this national drama, are they being recognized in Yiddish literature, thanks to Eliyohu Lipiner.

Approaching The Ideology of the Hebrew Alphabet, we apologize at the outset, as a proper analysis of this ramified, broad, and profoundly challenging work is better suited to an expert linguist, or rather a historian on religion, or an expert on Kabbala. Although the title seems to imply a limited subject – the alphabet – the book is extremely rich.

In another language, for a different people, a title such as this is unimaginable. An alphabet has no ideology. Indeed, what could letters desire? After all, they are no more than graphic tools that embody sounds. There is a long–standing argument whether a language is only a technical instrument or something more: a reflection of the soul of a people. But the letters have never had ascribed to them anything more than their technical function. We're afraid that Lipiner's title would be completely unintelligible to a non–Jew. How differently a Jew views it!

We, too, cannot simply agree with the title. On the contrary, we would have formulated it even more grandly: “The Philosophy of the Hebrew Alphabet.” We believe that the content of this multifaceted, comprehensive work deserves nothing less than a comprehensive, metaphysical title. In any case, the title indicates that the letters of our language are not ordinary tools but bear a mission, or that mystical forces, emanations, move them to a mission. In Kabbalistic terms, which were later

[Page 161]

transferred to Hasidism, these are referred to as coming from the World of Creation.

Lipiner's work is based on Kabbala literature, that phenomenon of Jewish faith which was opposed by both halachic scholars and scholars of the Enlightenment, although for centuries Kabbala accompanied official rabbinic literature, and some renowned halachic authorities were also scholars of Kabbala, such as the codifier Joseph Karo, author of the Shulchan Arukh.[22] Kabbala was not only sealed to the general community because of its Aramaic language and its complicated “secret” speculations on the significance of letters, words, and verses; it was also warned against and forbidden. Kabbala literature was surrounded by great mysteries. Its students always mentioned it in whispers, with some fear, and secret trembling. People were afraid to touch a book of Kabbala, and it was outlawed from some bookshelves, as if it emitted witchcraft and was therefore dangerous to ordinary people. Kabbala books, such as The Book of Creation and the Zohar itself, were therefore kept hidden away and circumscribed by legends about their origins and authors.[23] The Zohar was translated into Yiddish by Zvi Hirsh Katz, but was sealedbulous for the same reasons and never gained the same popularity as the Tsene–Rene, though it was written with the same rationale.[24]

Through his Ideology of the Hebrew Alphabet, Eliyohu Lipiner has opened the locked gates of this mysterious world and has given us a flash of a fabulous beauty, a dazzle like that of the secret light of hidden worlds. We are astonished as to why various rationalists could oppose Kabbala for no reason, without penetrating into its world. They considered it a kind of dark hallucination, superstitious witchcraft; and did not notice that it is actually the eternal impulse of the lost individual towards the infinite universe.

This fantastical quality is woven and integrated into our alphabet. Lipiner was able to elicit admiration, even among critical and rationalistic readers, for the poetic quality that shines out artlessly from the Kabbalists, and for their tragic struggle to suppress and strangle the devil within them while desperately clinging to the Creator and his creation.

Our alphabet was primeval, an outgrowth of cosmic creation. In philosophical thought it is a nuance, a variation of the thought that acknowledges the priority of the divine; on further reflection, it is a transition to the Spinozist principle that God and nature are one and the same, as are spirit and form. Is it possible that the genius of Amsterdam studied Kabbala during his ascetic nights?…

The author investigates all of Kabbala literature, which interprets every letter, every vowel, every small mark and intonation. In Kabbala, they are all emanations of the world of Creation, even predating the Creation… This is certainly an objective, rational study by a twentieth–century scholar, and no idle rumination. In his devotion to the subject, to the poetic impetus and the cosmic exaggeration of the masters of secrets, as he terms them, and their complex and challenging manipulations and speculations on the meanings of letter combinations, numerical values, and the fantastical spheres, he transforms scientific objectivity into a kind of “poetic objectivity”… It is not the beauty of truth but rather the truth of beauty…

This leads, in our view, to the mysterious power of the book; that is, to Eliyohu Lipiner's writerly strength, with which he has constructed such a compact and complicated architectural structure. We believe that the Ideology of the Hebrew Alphabet will serve as a studio for Jewish researchers, both because of the pioneering terminology for a wealth of Kabbala concepts and the transmission of minimal texts, as well as because of the fantastic nature of the language, which in Lipiner's hands seems to have been reborn with no superfluities. In the magical sea of the Kabbala, which consists largely of the Aramaic that the writer has fully mastered, a Yiddish translation of the Aramaic translation has been born.[25] We will not attempt here to compare it with the Yehoash translation, which includes the entire Bible, but show only that, while Yehoash had at his disposal an entire scholarly tradition, Lipiner had only his own aesthetic intuition and created his own language and style.[26]

It really is a work that deserves a special blessing. Such a book is unique, in scope, thoroughness, and exhaustiveness. It is one of the greatest achievements of Yiddish literature and the Yiddish language. Lipiner has bridged all the historical periods, discovered the connection of the Kabbala with the alphabet that connects, through the channels of anonymous folklore, to the idealization and love on the part of our generation. This love, which is rooted in us all, was defined and studied by Lipiner.

[Page 162]

We doubt whether this volume could have been written in, or about, another language. For several reasons, The Ideology of the Hebrew Alphabet was destined to fulfil its mission in Yiddish. However, this is only a fleeting impression. Essentially and ideologically, Lipiner's book is not linked with any definite period. On the contrary, all the 600 pages yield the pleasing thought that our square letters were, and are, partners in Creation, and are woven into its foundations. Our 22 letters will continue to exist as long as the world exists.

Gershon Kirszhner

| Khotyn

Cemetery town, my Khotyn,

Separated like life from death

You sleep for a long winter

Forgive me, Khotyn,

Khotyn, |

[Page 163]

|

| Life is Hard

Life is hard, life is hard

Where one must always be on guard

Life is hard, life is hard,

Its fingernails sharp

Life is hard, life is hard

Where life is divided:

Life is hard, life is hard,

Oh, it's hard, it's hard to live |

| Autumn Night

Gloomy clouds float high

The angry wind roars, cold,

Between the earth and sky |

[Page 164]

| I Confess

Well, I give up now,

I toiled in vain

No longer whole was my heart,

And it asks: where is your dream,

I confess: I've already lost.

I will hear, see, and shut up.

The world will love me |

|

| By the Dniester

For Feyge Roitman, my mother, and others murdered by the German killers.

The rushing Dniester is loud,

Grandpa comes down at twilight,

I put on my shirt, and angrily

Zigzagging down the hill. 1946 |

[Page 165]

| Late Summer in Khotyn

For Mendl Roytman, my father, and others murdered by the Russian Fascists

The heavens here seem to be locked.

And the children in the evening alleys

Night… eyes float away from balconies…

The road suddenly widens and lengthens,

Until a door creaks open and drives away 1957 |

| In the kheyder

I still hear the rebbe's voice

I hear it still, the rebbe's voice,

I know what's in store,

Dad will give me

But tomorrow I'll clearly hear

The rebbe will slap |

[Page 166]

|

|

|

Translator's footnotes:

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Khotyn, Ukraine

Khotyn, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 05 Feb 2023 by JH