|

|

|

|

The Second Relocation Action to Riga

| - Measures taken by the Jewish Ghetto administration to recruit the required number of people to be sent to Riga. -Tense course of events at the end of the recruiting period. |

[Page 126]

By end of October 1942, when it became clear that for the second time the Ghetto must give up 300-400 Jews to work in Riga, the situation in the Ghetto once again became tense.

Of course, at the start, the atmosphere for the second relocation Action wasn't as desperate as it was during the first relocation Action in the beginning of February 1942. The most important detail was that this time no one doubted that this was truly about traveling to work and not, God forbid, about an extermination Action.

The regards sent from those who were transported to Riga eight months prior, were not too bad, also in Riga, at that time, the Jews worked in varied forced labor and lived, approximately in similar conditions to the Kovno Jews.

Here, no one wanted to lose their established position acquired during the time of the “achievements.” They didn't want to start from the beginning, building a new life somewhere in new, unfamiliar conditions.

The situation for those Jews was different. In the first relocation Action they were transported with close family members, full of people like a husband, a wife, children, elders, etc. So, right at the start they were prepared to go to Riga even voluntarily, to be together with one's own.

The Elders Council, which was given the task to recruit people for Riga by the regime, understandably tried to take advantage of this atmosphere and on their part, got volunteers who were even promised material support to go to Riga.

The total number of volunteers for the pre-registration, however, was not large. Therefore, also this time, it was more than certain that they would have to recruit people in a coersive manner.

Once again, a panic and a nervousness arose from those ghetto Jews, who they themselves bet that they would eventually fall onto the list of persons who would be forced to go to Riga. This panicked atmosphere also negatively affected the position of those who volunteered.

Day by day, the total number of volunteers going to Riga actually diminished. The original registrants who voluntarily registered to go to Riga, renounced their readiness to travel en masse.

These same people who renounced their registration, were still being considered on the part of the Jewish ghetto administration as the most suitable candidates for the relocation to Riga - whether they wanted to go, or not.

A few days before the people were to be sent off to Riga, when the Jewish Ghetto Police began detaining the designated people, the atmosphere in the Ghetto became highly charged. People started taking the only possible measure: to hide themselves from the Ghetto Police.

Many also stopped going to work in the city, so they shouldn't be stopped at the Ghetto Gate on their return from work. Once again, the air in the Ghetto became filled with horror and pain.

At that time, the Ghetto Police continued detaining the designated people. As was the case when the recruits were transported, this time many detained people who also had connections with whomever from the higher Jewish ghetto administration, tried through their close connections to get themselves freed. In place of those who were allowed to go free, they had to detain other persons. The feeling of torture and shock increased even more.

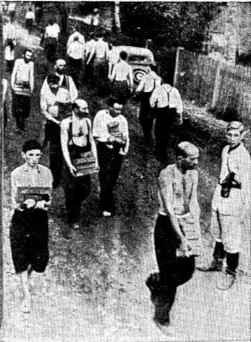

A day before the departure of the transport, they still didn't have the needed count. The rest were captured near the Ghetto Gate from those returning from work. This time the Jewish authorities carried it out themselves.

In order not to raise suspicions that they were being taken to Riga by those who would be stopped at the Ghetto Gate, the Jewish Ghetto Police completely unexpectedly carried out a search of those returning from the city. This search was about whether their yellow patches were attached according to the regulations of the regime.

Those people whose patches were not in order, that is, those who they wanted to detain, were taken into the Ghetto Jail which was located near the Ghetto Gate.

This “contrivance” by the Ghetto Police was figured out very quickly. However, those who were detained were already in the Ghetto Jail under guard and had no choice but to make peace with their fate to be relocated to Riga.

The Jews were deathly afraid of the Gestapo murderer, Shtitz, because of the great number of Jewish victims he killed. This same person, in charge of Jewish affairs in the Gestapo, could at any moment, without the least reason, deport Jews to the 9th Fort and shoot them there by his own hand. At the Ghetto Gate, this proved to be the most awful strain for the ghetto folk during the time the transport was sent to the train.

On the neighboring street around the Ghetto Gate many friends and acquaintances came to accompany those Jews who were to be sent off. But, with the arrival of the hangman, Shtitz, this meeting place immediately emptied of people. Each one was afraid to find himself in the proximity of the Nazi murderer whose name alone would conjure up horrific associations of bloody executions of Jews at the 9th Fort.

Even those Jews who were sent by transport, had to control their strained feelings with all their friends and acquaintances while leaving the Ghetto for the last time. They did not make a sound as they marched by the bloodthirsty Jew-murderer, Shtitz.

Going through the Ghetto gate and seeing Shtitz in the distance about a hundred meters away, they could have cried out their fate undisturbed – the bitter fate of the ghetto Jews, who were condemned until their destruction to suffer in the horrible Nazi hell…

A Hanging in the ghetto

| - The doomed young Jewish man, Mek, who shot a German member of the Ghetto-Command. - Immediate Gestapo investigation. - Arrest of the Council Elder and his release. - The public hanging of Mek. |

[Page 130]

After the second relocation Action to Riga, a few, so-called, quiet weeks transpired without any shake-ups in the Ghetto. A critical moment for the Ghetto took place in the middle of November 1942. This specific, unexpected crisis took place in the following way:

It was Sunday night, the 16th of November 1942. A Jewish young man by the name of Mek, a man in his 30's, a former owner of a watch and jewelry shop in Kovno, together with two other friends, decided to pose as non-Jews and sneak out through the Ghetto Fence at a specific time to “arrange” something in the city. One of the three youngsters managed to get through the Ghetto Fence successfully, and Mek went after him. But he got caught up on the barbed wire of the fence, and because of that he was noticed by one of the guards who ran to arrest him. The third young man, who was supposed to go through the fence after Mek, understandably didn't go, and immediately disappeared into the Ghetto.

By coincidence, a high functionary of the Ghetto Guard was in the vicinity - a Viennese German named Fleishmann. When Fleishmann ran up to Mek to arrest him, Mek grabbed a revolver out of his pocket and started to shoot. He didn't hit anyone, but he was immediately arrested.

Notification of this specific surprising event spread through the ghetto population with lightning speed, and it created unexpected confusion, because this was the first instance where a ghetto Jew dared to raise arms against a German, especially against such a high German ghetto official. It stands to reason that this would cost the whole Ghetto many victims. Not to mention the mere fact that there was a Jewish attack on a German, they were afraid that this incident would serve as a pretext by the regime to accuse the entire Ghetto of having personal arms.

[Page 131]

At this moment, Jews reminded themselves that in Autumn of 1941, there was no more than provocative confusion about a so-called shot from a Jew on the then-chief of the Ghetto Guard, Kazlovski. Thereafter, the first mass Action in the Ghetto took place, which cost the ghetto population over 1000 victims. What awaited them today in the Ghetto when an attack of a Jew against a German really did take place?! That's how the Jews explained and imagined horrific scenes. Therefore, it was with great nervousness and strain that the Jews awaited the sanctions for the Ghetto from the occupation regime.

In an hour or two after this event, the representative of the Gestapo, together with the chief of the German Protection Police arrived in the Ghetto and started an investigation of the issue. The strain in the Ghetto became even greater when it became known that because of the first investigation, all the members of the Elders Council were arrested, except for Chairman, Dr. Elkes, who was at that time sick in bed.

From the investigation, the Jewish Ghetto Police was ordered to immediately arrest 20 Jewish hostages, until Mek's friend, the one who got through the Ghetto Gate and disappeared, was found. It was fundamental to wait, because the hostages could become victims if they weren't successful in finding Mek's friend, so the Ghetto Police detained men and women from the mental institution and those hopelessly sick, as hostages. This was done with the intention that no healthy persons or heads of family should suffer in case the bloodletting will come.

[Page 132]

Right after the first investigation, the members of the Elders Council were transported to the Gestapo. The Jews perceived the arrest of the members of the Elders Council as a bad sign, and it strongly increased the unrest in the Ghetto, because of the anticipation about the next day, when the mood of the regime would become clearer in resolving this issue.

At this time the Jews used everything in their power to “soften” the hearts of those Nazi-rulers, on whom the course of the investigation was dependent. The fact that in the shooting, Mek did not target the German, Fleishmann, and that he only shot in the air, played a certain role in the investigation, which was the real gift that benefitted the Ghetto.

Finally, through many efforts, they succeeded in establishing the entire issue on such a plane, that Mek was not a public emissary of the Ghetto and that his act was committed according to his personal initiative. He wanted to run away from the Ghetto for fear of an extermination Action. Aside from everyone, it turns out, the Kovno Gestapo this time didn't have a great desire to make a big deal of this issue and the next morning freed the members of the Elders Council from arrest and sent them back to the Ghetto.

Despite everyone, the Gestapo had already decided to hang Mek in the Ghetto. True, when the judgement of the Gestapo became known, the Ghetto breathed easier, because they had expected sanctions on a mass scale. Nevertheless, the ordered execution of Mek by hanging hurt everyone strongly because this was the first case of hanging of a Jew in the Kovno Ghetto.

Tuesday, the 18th of November, was the day when it was decided to carry out the execution of Mek. The Jews themselves had to prepare the gallows, which was stationed in an open plaza opposite the Elders Council building. Mek, who was already in the Gestapo where he was murderously battered until the hanging. However, he held himself valiantly, very tranquil and his first question before going to the hanging was about the fate of his mother and sister, with whom he lived together in the Ghetto.

[Page 133]

The representatives of the Jewish Ghetto Police, who had to prepare the hanging, and be present at the execution, calmed him, saying that all is in the best order. The truth was that the Gestapo sent his mother and sister to the 9th Fort where they were shot, even before they hanged Mek.

The then-representative for Jewish affairs in the City Commissariat, the S.A. man, Miller, wasn't very lazy about running into the neighboring Jewish houses, in order to force the available Jews to be present at the execution. All Mek's possessions[a] were transferred into the private custody of the Gestapo murderers, who dealt with the situation.

Mek's body hung on the gallows for a long period of time. It is not difficult to understand the feelings of the Jews that day…a cold late Autumn wind blew Mek's small and stretched out body back and forth on the gallows. The noose on Mek's neck, even more than any other day, didn't allow the Jews to forget their tragic hopeless fate.

After it became clear that the Mek issue was finally over, the hostages were freed. After a while, the Ghetto quieted down, but not for long, because a new period of permanent unrest started for the Ghetto with the arrival of the year 1943. This was a period when important changes took place in ghetto life, which had a decisive impact on the future fate of the ghetto Jews.

Original footnote:

“The Stalingrad Action”

| - The measures taken by the Nazis to prevent Jewish satisfaction and joy over the German defeat at Stalingrad. - The course of the Action, which claimed 50 victims from the Ghetto. |

[Page 134]

In January 1943, the situation became more critical for the encircled German forces near Stalingrad. It was sensed by everyone that here, near Stalingrad, the downfall of the German Army on the Eastern Front would begin. Thus, the mood in the Ghetto became more cheerful, day by day. Jews clearly saw that their long-dreamed hope to be freed from Hitler's hell, slowly started becoming a reality.

As they got closer to the end of January, even the German military High Command couldn't hide its reports from the front. With the indomitable German catastrophe near Stalingrad, the faces of the ghetto Jews started shining and expressed happiness and revenge. Finally, the historic Battle of Stalingrad ended with a roaring win for the Soviet Union, and with a shake-up defeat for the Nazi-Germans.

When the Third Reich proclaimed a day of national mourning pertaining to the defeat near Stalingrad, it was a real, long-awaited holiday for the ghetto Jews. Not only in the Ghetto, but even in the city at work among the Christians, Jews shared their feelings of happiness and held their heads higher.

On the other hand, however, it was to be expected that the Nazi murderers would mar the happiness of the Jews. Unfortunately, the Jews didn't have to wait long for such a step to take place by the Gestapo. They soon made them forget about the German defeat and move on with their own problems.

[Page 135]

On the 3rd of February 1943, a few days after the final German defeat near Stalingrad, a few dozen Jews were arrested in the city by the Lithuanian police, according to a decree from the Gestapo. Until then, Jews would very often go out in the neighborhood near their workplace to illegally buy some food products. Most of the time they would get through successfully. But on this day in the city, any Jew who tried to walk even a short distance from their workplace, was arrested.

Truthfully, Jews themselves took great care not to fall into the hands of the Gestapo. They knew in advance that the murderers were infuriated because of the German defeat, and now more than ever, would not let the Jewish victims out of their grip under any circumstance. So, on this day in the city a few dozen Jews were arrested for buying a loaf of bread, a few potatoes, a newspaper, etc.

In addition to the Jews arrested in the city, the murderer Ratnikas, the Chief of the Lithuanian Police of the Ghetto Guard, also arrested a certain number of Jews inside the Ghetto. These were mainly the bosses of the secret food stores. His “pretext” was fighting against black marketeering in the Ghetto.

Those arrested in the city were taken to the Gestapo, and those arrested from the Ghetto – to the Ghetto Jail. The Gestapo also ordered the Jewish Ghetto Police to detain all the family members of the arrested, both from the city, as well as from the Ghetto.

Knowing what kind of tragic fate awaits their family members, most of those Jews arrested in the city, would not divulge that they had family members in the Ghetto during the Gestapo investigation. In this way many family members of those arrested men were saved from a certain death. In total, close to 50 Jews were detained, both from the city as well as from the Ghetto, among them men, women, and a few dozen children.

On the morning of February 4th, 1943, while transporting the arrested from the Ghetto Jail to the Ghetto Guard, gruesome scenes played out. Finally, the arrested were seated on sleds in which they were transported to the Ghetto Guard, where Gestapo people were waiting for them.

[Page 136]

The convoy of sleds, on which were seated those convicted to die, looked like a funeral of living dead. They knew all too well what awaited them in a few hours at the 9th Fort. Exhausted physically and spiritually from the horrible experiences, they prepared themselves mentally for the upcoming execution, and looked at the Ghetto with resigned looks - for the last time in their lives.

At this time, the tragic and infamous truck of the Gestapo was seen as it passed by the Ghetto in the direction of the 9th Fort, in which sat the Jews arrested in city. Twenty minutes later the same truck came back from the Fort and drove to the Ghetto Guard to collect the rest of the Jewish victims.

The Gestapo executioner, Stitch, who conducted the execution, came to the Ghetto Guard, to oversee the transport of the Jews convicted to death. His presence near the Ghetto population raised the possibility of getting closer to the Ghetto Guard and for the last time, get a look at the few dozen Jews who would, in an hour or two, be killed. Among the victims was also the well-known Kovno Russian Jewish journalist Boris Oretshkin, and his wife. They were arrested just the day before by order of the Gestapo because their child, who was hidden in the city by Christian people, was discovered there by the Gestapo.

[Page 137]

It was a cloudy winter morning, when the Ghetto paid with the lives of exactly 50 Jews. The blood bath was organized by the Gestapo to remove the happiness about the defeat. The Hitlerites only partially accomplished their goal. The mood in the Ghetto was really very low due to the exterminated victims, but this atmosphere of grief couldn't completely erase the raised feelings of happiness and revenge of the Jews.

In the history of the Kovno Ghetto, this Action comes under the name “The Stalingrad Action.”

Important Events in the Ghetto in the Spring and Summer of 1943

| - The project of relocating some 4 -5 thousand Jews from the Vilna region to the Kovno Ghetto. - Also bringing some 800 Jews who worked in the Zhezhmer area to the Kovno Ghetto. - The Gestapo accusation that the Ghetto Jews were sending “signals” to Soviet aircraft. - Vague rumors about the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. - Attempts by the first Jews in the Ghetto to join the partisans in the forest. |

[Page 138]

With the arrival of Spring 1943, the signs became clearer, from one week to the next, that the Ghetto was heading for an indomitable crisis. The reason for this upcoming crisis, first lay in the situation of the war operations on the Eastern Front. It was becoming clearer that the Red Army was overpowering and forcing the Germans to retreat from the occupied Soviet areas. Because of this, the Nazis became even more irritated than before, when they were certain of their victory. This nervousness of the Hitlerites in this regard, was felt in their relations with the clusters of still-existing ghettos.

For some specific reasons, the Kovno Ghetto colony had a longer, comparatively, peaceful break, when no significant events took place. At that time, the Kovno Ghetto Jews started to strongly feel changes for the worse. Moreover, the Jews in the Ghetto actually felt that the problems were closer, rather than, further. But the degree of uncertainty about when, and mainly how the ball of thread will unwind itself, kept them from enjoying the worsening of the German campaign on the fronts. This situation forced the ghetto Jews to keep their eyes open for everything that was happening around them.

In the beginning of March 1943, the occupation regime from the Vilna region decided to liquidate the remaining smaller ghetto colonies in Oshmene, Smargon, Olshan, Kreve, Varnian, Michalishok, Svir, etc. In these points around Vilna there still were approximately 5,000 Jews. These steps by the regime were based on its plan to slowly clean out the few surviving Jews from the Eastern areas. What was the connection between the Jews from these smaller ghettos around Vilna? We must say that they were viewed with an evil eye by the regime, because these ghetto colonies were close to the partisan nests in the forests between Vilna and Minsk. An apparent movement to leave the Ghetto to go to the Partisans, was already noticeable.

As we know, at the end of 1941, the area above White Russia was transferred to the general region of Lithuania. By that time, the extermination of the Jews in the provinces had already ended, and in White Russia they just started the systematic extermination Actions on a wide scale. The remnants of the Ghettos remained in existence thanks to the accident in which they became incorporated within the borders of Lithuania.

At first, the Kovno City Commissar and boss over the Ghetto agreed to allow the Jews of the Vilna region to be brought into the Kovno Ghetto. The Vilna Ghetto, at that time, was already standing on the eve of liquidation, so there was no discussion about transporting the Jews from the Vilna Ghetto.

The Elder's Council of the Kovno Ghetto, on their part, had already anticipated a plan of how to bring these Jews into the Ghetto, and set them up with a roof over their heads. But, at the last minute, the Kovno Gestapo did not allow these Jews to be brought into the Kovno Ghetto, even if it could take responsibility for them, because “they are all partisans…”

[Page 140]

The issue ended fatally for these Jews. In the beginning of April 1943, the local regime organization reported to the Jews that they are transporting them over to the Kovno Ghetto. At first the Jews believed it and let themselves be transported. Enroute, they saw that their train was really being brought to the Ponar station. A horrible panic broke out among the Jews, and they started tearing up the closed wagons in which they were being transported, trying to run away. The accompanying guards immediately opened fire on the Jews with machine guns. Many Jews put up resistance against the murderers and killed a few of them. As a result of this fight a few dozen Jews succeeded in disappearing, but all the others were shot in Ponar.

The horrible fact that the Jews from the Vilna area were killed, completely frustrated the illusion for the majority of Kovno Ghetto Jews, that the time of mass-murders is already over and there would be no more such killings of Jews. On the contrary, it was obvious to see that the infuriated evil Hitlerite animal had not completely resigned itself from its original program of total eradication of the Jews who found themselves in their grasp. And if Jews had reason to be pessimistic, unfortunately, it was quickly confirmed.

Between us, a bigger group of Jews from the aforementioned ghetto colonies from the Vilna neighborhood were employed in the construction of the Vilna-Kovno highway. In May 1942 approximately 600 skilled men and women from the Ghettos in Oshmene, Smargon, Olshan, Keve, etc. were brought to Zheshemer[a] during the construction of the highway. These Jews worked at “O.T.,” i.e. Organization Todt.”[b] A second group of Jews worked on the same highway not far from Yavieh, near Vilna.

In Zheshemer, the Jews were quartered in a former Beit Midrash [house of study], and in a movie house. In these same buildings, in unsanitary conditions, Soviet prisoners of war were held before the arrival of the Jews. Due to this, right after the Jews' arrival, an epidemic broke out from which many people died, among them also the Jewish leader of the camp, Reuven Segalovich, from Olshan.

[Page 141]

The Jews lived together fairly well with the people from the “O.T.” So, for example, each week a car would travel from Zheshemer to bring food products for the Jewish camp from their homes near Vilna. Together with food, relatives of the Jewish workers would also join and stay to work in Zheshemer.

On the eve of Spring, 1943, when they were about to liquidate the Ghettos around Vilna, there were another 700 Jews, among them many small children, who were brought to Zheshemer. In the Zheshemer camp in total, there were about 11-12 hundred Jewish souls.

In Summer of 1943 the work of constructing the highway ended. About 300 Jews from “O.T.” were brought to another workplace. It was unknown at first what they would do with the remaining Jews. However, the danger was understood, that they would kill them because they were “unnecessary” Jews.

The Kovno Elders Council, which was previously in contact with the Jews in Zheshemer, started to use their connections with Herman, from the German Work Office in the Ghetto. They wanted him to arrange permits through the City Commissar for these Jews to be transferred to the Kovno Ghetto. The City Commissar had to officially state that they were needed as a work force for important workplaces.

Finally, the regime divisions agreed that the skilled Jewish workers be allowed into the Ghetto. The person from the German Work Office was not trustworthy to choose the suitable people, therefore, a few higher Jewish Ghetto officials went together with him. With the people from the German Work Office, they were successful in silently transporting into the Ghetto not only the skilled workers, but all the Jews from the Zheshemer camp. About 800 Jewish men, women and children were brought into the Kovno Ghetto in June 1943, and, in this way, they saved them from certain death.

[Page 142]

In the beginning, the “Zheshemer Jews,” as they were called, were very warmly received in the Kovno Ghetto. According to their various means, they were willing to help them with whatever possible. Unfortunately, we must establish that later the Jewish Ghetto Administration was not always objective toward these Jews. Looking at them as “inferior” Jews, they would, for example, plug up all the holes when they needed people for difficult work positions outside the Kovno Ghetto.

The largest portion of these Jews were taken to Estonia during the Relocation Action, which took place on the 26th of October 1943.

In the Spring of 1943, the Soviet air war visited Kovno from time to time, and bombed the city a few times. There was no need to say that the Jews had great enjoyment from the bombing and saw this as the start of their salvation.

The Kovno Gestapo circles were not unfamiliar with the attitude of the Jews to the Soviet bombardment. To keep the Ghetto in a permanent irritated mood, the Gestapo blamed the Ghetto for signaling to the Soviet airmen during the time of the air attack.

In addition, at that time, the entire issue became sharper through the following events:

Among the German labor positions, where ghetto Jews were then working, there was also a Jewish work brigade near a large munitions camp, which was located at the 5th Fort, near the Kovno suburb, Panemun.

To get arms for the youth who were preparing themselves to go out of the Ghetto into the woods to the partisans, the leftist circles in the Ghetto sent a few of their members to this very brigade. They would find suitable opportunities at work to steal arms parts and afterwards smuggle them into the Ghetto when they returned from work.

[Page 143]

One day in March 1943, at the Ghetto Gate, the checkpoint where all Jews were checked before going in or out of the Ghetto, one young Jewish man, by the name of R. Berman, was detained from the aforementioned brigade, as he wanted to smuggle a small rocket part into the Ghetto. The young man was arrested, of course, and was immediately taken to the Gestapo.

Because of Liptzer, who had high connections in the Kovno Gestapo, and who, by the way, also wanted to maintain good relations with the leftists in the Ghetto, did everything he could to free Berman.

After a few weeks, Berman was actually freed, but the Gestapo already had another “argument” to strengthen its provocative charge that the Ghetto was “signaling” to the Soviet fliers.

This issue, which went on for a few weeks, caused the Ghetto plenty of anxiety, because there was suspicion to believe that the Gestapo was looking for a “reason” to conduct an Action. The situation in the Ghetto became particularly strenuous just during the week of Passover. It gave the impression that the Gestapo was doing everything purposely to put augmented strain on the Ghetto during Passover time so that the Jews should have a disturbed “holiday.”

Finally, the Elders Council succeeded in washing the Ghetto clean of this Gestapo provocation after long arguments and answers.

Although the Ghetto was strongly isolated from the outside world, news arrived about the uprising and liquidation of the Warsaw Ghetto. Additional details about the uprising were not known in the Ghetto. They only knew that at the liquidation of the Warsaw Ghetto, the Jews set up an armed uprising and the Germans had to bring in special tanks, artillery, and even airplanes against the Jews.

[Page 144]

To get credible news about the issue, the Elders Council tried to connect with contacts in the Vilna Ghetto, which was geographically located closer to the Warsaw Ghetto and were able to get more news than in the Kovno Ghetto. They also tried to reach Christians in the city. Individually they were only successful in reaching a Christian who had travelled through Warsaw just during the days of the revolt and heard the cannon fire of the fighters and saw how the Ghetto was burning in flames.

The more settled ghetto Jews took the news about the uprising in the Warsaw Ghetto with a strong tense feeling. However, the news about the revolt made a strong impression on the active youth and stimulated them to search for resources and strategies to quickly to stand up among the rows of fighters against the Hitlerites. Just then, in the life of the Ghetto, these social circles took on greater importance, and called to organize groups of youths to go out of the Ghetto into the forest to hook up with the Partisans. After a while, from the fright in the Ghetto, an entire movement started to take on an unexpected role in ghetto life.

The news about the revolt and liquidation of the Warsaw Ghetto strongly shook up the Ghetto population and forced every ghetto Jew to think even more about their future fate.

As is known, the strategic situation on the German-Soviet Front later in the Summer of 1943 became even more catastrophic for the Germans. Everything aside, the Soviet victories strongly contributed to the growth of greater partisan forces behind the enemy, which undid German contacts both in people, and in war materials.

At that time, in the Kovno region there was no partisan activity for two fundamental reasons: firstly, Kovno was very far from the front lines, and secondly, the Lithuanians, almost as a rule, were hostile to the partisan movement. The closest partisan nest in the forests around Vilna were approximately 50 kilometers distance from the Ghetto.

|

|

|

|

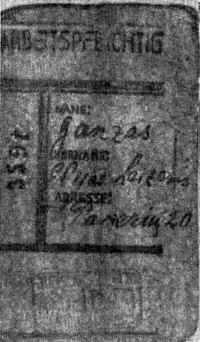

Top left: A work duty card from the Kovno Ghetto |

|

|

| Map of the massacres of Jews, conducted by the Gestapo and its accomplices, at the end of December 1941 in Lithuania (excluding Vilna and region) as 136,421 Jews were already murdered. The only ghetto settlements that remained were in Kovno (16,000 people) and Shavl (4,500). |

|

|

[Page 145]

Because of that, there was no objective possibility that larger groups of Jews from the Kovno Ghetto would be able to link themselves to the partisan movement. However, the drive of the ghetto youth to get out to the Partisans was growing in parallel to the Soviet victories and to the German defeats.

At that time, the first concrete steps were actually taken so that groups of youths could get out to the Partisans in the forest.

The initiative to organize the partisan movement came from the leadership of the left-leaning elements in the Ghetto, at the head of which was a Kovno young Jewish writer, Haim Yellin.[c]

Not only in the Ghetto, but even in the city of Kovno itself, the underground leftist movement at that time was very weak. But that movement started to revive itself and displayed signs of greater activity.

The contact between the left-leaning elements in the city and the Ghetto didn't take long to set up. Therefore, the various groups of youth, who were ready to leave for the partisans in the forest had to do it without informed help and instructions from outside the Ghetto.

A few dozen youth decided to go out of the Ghetto in various groups, and set out for the forests around Vilna, to find partisans. But the situation was such that it wasn't possible in any way to protect the route from these “spies,” and it wasn't known where one could find the partisans. But these youth were determined not to remain in the Ghetto, and they got themselves out in various ways – by smuggling themselves out through the Ghetto Fence, or by running away from the workplace in the city – abandoned out on the road.

The result of this first attempt to escape to the partisans was very tragic. Almost all those who left the Ghetto were arrested on the way by the Lithuanian Police, who had the Jews delivered to the Gestapo.

[Page 146]

Not knowing the fate of the first group, a few other groups of people went out and fell to the Gestapo. When it first became known that this is not the right way, no more people from the Ghetto were allowed to go this route in this manner. They started searching for safer ways and means to get through to the partisans.

But not only the left-leaning elements had the urge to go out to the forest. Also, many young people from the other social groups were ready to put themselves in line for armed resistance against the Nazis. Thereafter, an even riper idea arose in the Ghetto, to create a secret committee of representatives of the various social streams, like the Communists, Zionists, etc. Thus, the partisan topic could be planned on a broader plane, according to safer possibilities than before.

At this opportunity, it is important to add that at the beginning of Spring 1943, a certain Christian woman from Poland, Irena, had a secret meeting in the Kovno Ghetto. Irena, a middle-aged woman, who as a student, got close to Jewish life, and had a great interest in Zionism, especially for “Hashomer Hatzair- [the Young guard]”. During the Nazi years she was mainly devoted to establishing contact with the Jewish Ghetto settlement in Poland.

She came to Kovno from the Vilna Ghetto. The Vilna PPA (United Partisan Organization) had her assigned to reach the Kovno Ghetto and do what she could to connect the Ghetto defense to the partisan movement. Through her, they learned that the Ghettos in Warsaw and Bialystock were getting arms and preparing themselves to have a revolt against the Nazi murderers. The Vilna Ghetto was going the same way.

She was in the Kovno Ghetto for a few days and managed to hold secret consultations with “Matzok”[d] and with a few leading people from the social groups. She strongly promoted the idea that the only way is for the youth to tear itself out of the Ghetto and get out to the forest to the partisans.

Her visit indeed contributed to the fact that the partisan movement in the Ghetto soon took on actual and realistic expression.[e]

Original footnotes:

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Kaunas, Lithuania

Kaunas, Lithuania

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2025 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 06 Mar 2023 by JH