|

[Page 61]

The 1917 Revolution brought into the open Jewish political parties which, until then, were operating secretly and illegally.

From the start, the majority of the Jewish masses supported the Zeire–Zion and Zionist parties. This became evident when over 90% of the Jews voted for these parties in local city elections and in elections to the Kehilla (Council of the Jewish Community). The same results were shown in elections to the all–Ukrainian Rada (parliament) and to the Founding all–Russian Congress which the Bolsheviks dissolved by force.

In Kamenetz–Podolsk, the Kehilla president was the Zionist M. Zack and the administration was in the hands of an able executive, the Zeire–Zionist, Z. Fradkin.

During the first three years of the Revolution, Kamenetz–Podolsk was under Ukrainian anti–Bolshevik regimes; first the government of the Rada in Kieve, then the Getman's regime with the help of the Germans, and finally, the government of the Directoria (dominated by Petliura). Only in the spring of 1919, the local Bolsheviks seized power in Kamenetz–Podolsk for about six weeks and then in 1920, the Soviets took over and that ended the civil war.

Under the Constitution of the Rada, which gave national personal autonomy to minorities, the local Kehilla administered Yiddish and Hebrew schools and other cultural institutions, the Jewish Hospital and Home for the Aged; the Kehilla was also issuing birth and death certificates, wedding licences, etc.

Zeire–Zion and all other Jewish political parties supported a free democratic anti–Bolshevik Ukraine. But, the Ukrainian government in Kiev ignored the fact that Zeire–Zion was a major Jewish party and when it came to Jewish affairs, dealt with the smaller Jewish Socialist parties like Poalei–Zion, Bund, etc. This was only because the majority

[Page 62]

|

|

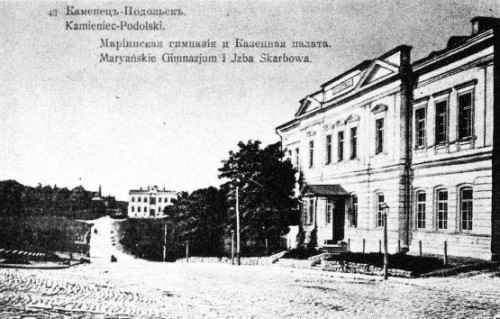

| Marinskaia Girls High School in Kamenetz–Podolsk in 1912 |

in the government were socialists. When the Petliura government under the pressure of the Red army retreated all the way to Poland (Galicia), some local Jewish Socialist parties conveniently forgot their allegiance to the Ukrainian government. In Kamenetz–Podolsk, the Bund, Poalei–Zion, etc., used the Bolsheviks to destroy the Kehilla and take over its functions. In 1919, during the six weeks of the Bolsheviks' occupation, Messrs. Guminers, Bograds & Company were reigning supreme over the Jewish community.

On the return from Poland in June 1919, the Petliura Government settled for a few months in Kamenetz–Podolsk, waiting for the liberation of Kiev. Among the ministries was the ministry of Jewish Affairs with Pinchos Krasny as Minister. He ordered the requisition of the Zionist Club building. The Pinchos Krasny appointed as heads of the ministry's departments the same Jewish Socialists who, only a few weeks before, had destroyed the Kehilla and cooperated with the Bolsheviks. Again, Guminer, Bograd & Co., held the power over the Kehillas which began functioning in Kamenetz–Podolsk and in all cities and towns liberated from the Red Army. The Kehillas ignored the

[Page 63]

Jewish minister, the Guminers & Co., whenever they could proceed without them.

The Zeire–Zion in Kamenetz–Podolsk still cut off from the central committee in Kiev, had to assume the functions of a temporary central committee. In mid–summer of 1919, a conference of Zeire–Zion was called in Kamenetz–Podolsk from all liberated territories. The conference was held in the city hall and was addressed by representatives of the Ukrainian Government. Of course, Pinchos Krasny was aware of the conference, but was not invited. In fact, among the resolutions at the conference was one condemning Pinchos Krasny as a self–appointed usurper. He came from the miniature Folks Party which did not have even a branch in Kamenetz–Podolsk or in any city in Podolia. I was in an unpleasant position as Chairman of the Conference. The next morning I had to face Pinchos Krasny again because, with the approval of my party, I occupied an important, though a non–political position, in the Jewish Ministry.

A memorandum pertaining to the political situation among the Jews in the Ukraine and a demand that a Jewish minister should come from a major Jewish party was presented in the name of the conference to the Directoria (Petliura, Prof. Schwetz and Makarenko). Z. Fradkin who had an audience with Prof. Schwetz was assured that, as soon as Kiev would be liberated and the Rada (Parliament) would begin to function again, a new government responsible to the Rada would take over from the Directoria.

Then a minister of Jewish Affairs would truly represent the Ukrainian Jewry. For the time being, we would have to contend with Pinchos Krasny. A few months later, the Zeire–Zion received an invitation to participate in the “Derjavna Narada” (Government Advisory Council) which was to serve instead of the Rada until elections to a new Rada after liberation.

Our party sent a delegation of three: Z. Fradkin, Dr. Halpern and Leon S (Schlomo) Blatman.

[Page 64]

The “Narada” took place on the main floor of the old Governor's house. Each Ukrainian, Jewish, Russian and Polish party (except communist) was represented. In addition to the Ukrainian clergy, the Army, the independent Ukrainian Guerrilla bands, the University and the Directoria were represented. The diplomatic corps consisted of a few Polish civilian and military representatives and Ukrainian diplomats accredited to, but not recognized by many European countries. Among them was Margolin (a Jew) who had tried unsuccessfully to represent the Ukraine in France.

When the usher examined our credentials, he asked if we wanted to be seated with the other Jewish delegates. We decline and took places near Prof. Ogienko, the dean of our city's university. After a while, the formal greetings were over and Makarenko in the name of the Directoria gave the report of the Government. As in the past, there were promises of a bright future after the liberation; the Ukraine would be a free democratic country. The national personal autonomy for minorities would give the Jews, Russians and Polish citizens a chance to enjoy more privileges than in any other country. The 100,000 Jewish victims of pogroms were dismissed with the explanation that it was the work of Bolsheviks who had infiltrated into the Ukrainian army. The Government gave the Jewish ministry a substantial sum of money to help the pogrom sufferers. Declarations by different delegations ensued. The Jewish Socialists made watered–down statements with hopes that the Ukraine would be the Socialist Paradise in contrast to the miseries of communist Russia. Finally came the declaration of the Zeire–Zion.

For almost half an hour, Fradkin kept the audience spellbound with his brilliant speech in excellent Ukrainian. He pointed out that millions of Ukrainian Jews were supporting Zeire–Zion and Zionists and were anti–communists. Even the Jewish Socialists were against the Bolsheviks. Notwithstanding, the Ukrainian army was crimson from the blood of Jews that had been killed in pogroms. The Ukrainians were

[Page 65]

|

|

| Certificates by Students' Council at Kamenetz–Podolsk University |

killing with the cry: “Kill the Jewish Bolsheviks”. The representative of the Directoria, who knew better, perpetuated the lie that the Bolsheviks were the guilty ones. It was enough to mention the infamous Ataman Zeleny whose bandits killed thousands of Jews and who were proclaimed to be real Ukrainian patriots, it was time to make an end to this pretence. Fradkin demanded court–martialling the guilty ones and a policy that would make pogroms impossible. Unfortunately, the Red Army appeared as the saviour of innocent Jews from the Ukrainian pogrom makers. Jewish youth, instead of fighting the communists, were forced to flee and join the Red Army to avenge the killings of innocent Jews. The Jews were in a dilemma: in theory, they were for a free Ukraine but fears of pogroms stopped only when the Red Army drove out the Ukrainians from cities and towns.

The pittance given to the Jewish Minister was less than a fraction of the sums extracted from the Jews by the Army as voluntary contributors. Millions were needed to rebuild the ruined Jewish population and they would have to come from Jews at home and abroad.

If the Ukrainian Directoria could not find a way to control and

[Page 66]

Discipline its army; the Jews of the Ukraine and from foreign lands were willing to organize a Jewish Legion, like Jabotinsky did in Palestine, to fight the pogrom makers to protect their lives and property. With the exception of the Jewish Socialists and the Russian delegates, the assembled applauded Fradkin's speech.

The Guminers and the Bograds now used the moneys Petliura gave the Jewish Minister to suppress Hebrew schools and other institutions, to buy off small Kehillas in towns so that they obeyed their directives and look to the Jewish Minister for a hand–out. In Kamenetz–Podolsk, the Zionists and Zeire–Zion, with the cooperation of religious and impartial groups, organized a relief committee to counteract the committee set–up, as an adjunct to the Jewish Ministry. Soon the representatives of the American Joint Distribution Committee arrived in Kamenetz–Podolsk and a programme for helping the sufferers was set up under the leadership of Jacob Schreier. In the meantime, the Red Army was pushing back the Ukrainian Army towards Galicia (Poland) and by November 1920, the last outpost, Kamenetz–Podolsk, was occupied by the Bolsheviks. The work of Zeire–Zion practically stopped. The leaders and hundreds of its members fled to Rumania and Poland and from there to Palestine and to America.

|

|

| Professor Israel Friedlander & Dr. M. Leff |

The border with Galicia (Poland) only 15 miles away from Kamenetz–Podolsk was opened in 1920 after being sealed since the start of World War I. After an absence of 6 years, mail started arriving from abroad and a few former residents of Kamenetz–Podolsk came from America to see what had happened to their relatives. These so–called “American delegates” brought money and visas also for others and their relatives. This started the legal exodus of Jews from the city. Later on, under the Bolsheviks, people secretly were escaping to Rumania or Galicia where they met the “delegates” and proceeded to America and elsewhere.

The American Joint Distribution Committee which had an office in Warsaw sent a delegation to Kamenetz–Podolsk. They had to survey the situation in the Ukraine and ascertain the relief needs of the Jews that had suffered from the pogroms. The mission arrived in May, 1910 and consisted of Professor Israel Friedlander, Maurice Kass and Dr. M. Leff. The three delegates represented different parts of American Jewry.

The “Joint” was composed of the American Jewish Committee (rich and influential Yahudim, descendants of German Jews) and the Peoples' Relief (a number of organizations of Eastern European Jews in America). To avoid the sending of relief missions by different organizations, the “Joint” agreed to include in its mission the delegate of the Federation of Ukrainian Jews of America. This delegate, Mr. Maurice Kass, editor of the Jewish newspaper “Die Welt” in Philadelphia was a man in his late fifties; a highly intellectual, literary personality; and a person close to the masses. He was ab excellent choice to bring relief to the

[Page 68]

sufferers in the Ukraine. Professor Israel Friedlander, although the choice of the Yahudim, was a personality to whom the Ukrainian Jews immediately felt a kinship. He was a man who understood the psychology of the Eastern Jews, who really felt their sufferings and was ready to help not only with money but with deep sympathy. He showed humility and understanding of the tragedy of the Jews in the Ukraine even though he, himself, was brought up in entirely different surroundings. Professor Friedlander, a man of the book, a historian and teacher, a deeply religious man and a Zionists became a friend to every person with whom he came in contact during his travels in the Ukraine. Dr. Leff was willing to take the risk involved in going with the relief mission to see, as a physician, in what way medical help could be brought to the people in that country.

Mr. Kass spoke Russian and Yiddish but now the knowledge of Ukrainian was needed. This was one of the reasons the mission needed a secretary who could also act as interpreter in dealing with the officials. Mr. Jacob Schreier, head of the Kamenetz–Podolsk Relief Committee, recommended me for the position because I had done some research on the pogroms and was familiar with the situation in many cities and towns. I also had command of Ukrainian which I had studied at the local University. An itinerary was worked out which would bring the mission into the larger cities such as Proskurov, Staro, Konstantine, Mohilev–Podolsk, Bar, Zhitomir and Berdichev. It was planned to proceed from there to Kiev or Odessa, whichever would be liberated first. We arranged stopovers in smaller towns between the cities. I introduced the Americans to the War Minister who supplied us with the necessary documents and notified all military and civilian authorities of our pending visits.

We were assured we would get full cooperation. On our arrival in a town, a welcoming committee was ready to meet us, present reports of what had happened in each town during the past two years and prepared plans as to how to alleviate the urgent needs in food, clothing, medicine, etc. The Relief Mission stopped in every

[Page 69]

|

|

| Turkish Bridge in Kamenetz–Podolsk in 1905 |

Town on the way to Proskurov. The Americans went to see for themselves the conditions under which the Jews lived especially in the poorer neighbourhoods. They could not believe their eyes when they saw the poverty, the squalor and the misery of these unfortunates.

We finally arrived in the city of Proskurov. This was the place where the Gaidamacks of Ataman Semosenko, only a year before, had slaughtered in cold blood hundreds of Jews on the pretence that they were suppressing a Bolshevik revolt. The investigation ordered by Petliura absolved the Jews of any complicity and no proof of a communist uprising could be found. Dr. Liser, head of the Kehilla in Proskurov and our host for the night, told us what had happened in his hometown in February 1919. Dr. Liser's son, also a doctor and recently from London, told us how he could not get any of his father's letters into the “London Times”. The editor could not believe the facts which the older Liser described in the letters to his son. Now the son came to see his parents and friends and planned to have a talk with the editor of the “Times” on his return to London.

Mr. Kass, a newspaper man, informed us that news of the pogroms were arriving from Moscow but that the American Press

[Page 70]

had dismissed this as a communist propaganda. He promised to publish in his paper the work of the secretary of the delegation who based his figures and stories on the documents from the Ministry of Jewish Affairs.

Dr. Liser had a report of conditions in Proskurov and of some nearby towns like Feldstin, Zinkov, Michaelpole, Derajna, Chan, Staro–Konstantine and others. The delegation expected to proceed north toward Jitomir and Berdichev but could only go as far as Staro–Konstantine. We passed a few towns where the reports turned in by the Kehillas showed that no place had escaped the pogroms during the past two years and that the need for relief was staggering. On arrival in Staro–Konstantine, we were advised to turn back. The city assumed that certain indescribable look, that unmistakable attitude that happened in every city before a retreat by one army and before the occupation by another. Usually, this was the time when a pogrom on Jews would start by one of the armies. Jews were running in search for places to hide or were leaving for another safer town. We were told that the Red Army under Marshal Buddenny had defeated the Ukrainians in a few battles north and east of the city and was proceeding west on all fronts.

We left Staro–Konstantine but instead of going south toward Kamenetz–Podolsk, the delegation decided to go south–east. We wanted to visit as many towns as were still accessible on the way to Mohilev–Podolsk. The military situation was changing from day–to–day and it seemed even from hour–to–hour. The Americans showed unusual courage and determination to do the best under the circumstances. The Federation of Ukrainian Jews in New York gave Mr. Kass a few hundred letters from its members to distribute to relatives in the Ukraine. On arrival in a city or town, Mr. Kass would turn over the letters to the local relief committee for distribution. Now we were anxious to leave the letters in the towns near the front before the Red Army cut off communications with the outside world. Professor Friedlander made arrangements for each relief committee to get funds from Kamenetz–Podolsk. We knew that relief money was expected in Kamenetz–Podolsk from Warsaw,

[Page 71]

sent with the American delegate, Dr. Cantor. We finally arrived in Mohilev–Podolsk where the river Dniestr separates the Ukraine from Rumania. This city, like other towns where we had stopped on the way, was tense with expectations of a pogrom from the retreating Ukrainians.

A meeting of the Kehilla with our participation was arranged by its president, the student Yampolsky. This able young fellow in a few well–chosen words appraised the Americans about the situation in the city and the surrounding towns. Like all over the Ukraine, the need for relief was great. During his talk, Yampolsky, in veiled language, let it be understood that another pogrom in Mohilev–Podolsk would be met with resistance from the well–organized Hagana. He made the remark, that this is not Proskurov – “for one Jew murdered, two Gaidamacks would be killed”. As if in answer to Yampolsky's words, a report was received that an incident had happened while the Kehilla was in session. A Gaidamack on horseback was passing through the deserted streets. When he noticed a lonely Jew hurrying toward a house, the Gaidamack raced toward him and started to beat him with a whip. Suddenly, a shot rang out and the Gaidamack fell dead from his horse. Immediately, a band of about 30–40 Gaidamacks galloped through the empty streets stopping only to pick up the dead soldier. A friendly peasant reported that it was Ataman Tutunik's band that was bivouacked outside the city. From talks with the Gaidamacks, the peasant learned that they were waiting for the Americans to leave in order to start a pogrom.

Other rumours brought the news that the Red Army had broken through the front in a few places and that the road to Kamenetz–Podolsk was not passable. Yampolsky closed the meeting and began arrangements for us to cross the Dniestr into Rumania. There we would try to reach Kamenetz–Podolsk by way of the city of Chotin. Within an hour, word was received by telephone from Bucharest that the Americans could cross the river and that they could include the Polish chauffeur and their secretary. Professor Friedlander suggested we stay overnight as there was no danger in the city as long as the Americans were still there. In the morning, word was received

[Page 72]

|

|

| Post street in Kamenetz–Podolsk in 1913 |

that the Gaidamacks were still waiting a few miles from the city but that the Red Army did not advance toward Kamenetz–Podolsk and that the road was passable. Dr. Leff fashioned from a sheet a white flag which was attached to the automobile on one side with the large American flag on the other. It was decided to confront the Ukrainian band and try to persuade them not to molest the Jews in Mohilev–Podolsk.

As a precaution, I was given Dr. Leff's spare uniform so that it would look as if there were no other witnesses but the Americans. We bid farewell to the representatives of the Kehilla and left Mohilev–Podolsk. A few miles from the city, we encountered Tutunick's band. Having been coached by the delegates, I addressed the Ataman and his troops in Ukrainian. I explained that a Bolshevik, a traitor hiding in the city, shot the innocent Gaidamack who was peacefully passing through the main street. I told them that the city commandant and the chief of police were of the same opinion and were searching for the murderer although it was most likely that he had escaped from the city. We wanted them to know that the American Government would not tolerate any further pogroms on Jews in the Ukraine. I called their attention to a speech recently made by Petliura who had said that any Ukrainian making riots, menacing

[Page 73]

Or hurting Jews is a traitor to a free, anti–Bolshevik Ukraine. I pointed out that they were need at present at the front to fight the Bolsheviks and that they should leave the peaceful Jews alone. I told them that the war Minister, a few days ago, had given us passes and had told us that he demanded cooperation from every commander of a Ukrainian military detachment. But the best argument was Professor Friedlander's peace offering. He handed the Ataman 10 five dollar gold pieces which were, as I explained, to buy cigarettes for his soldiers.

The Ataman talked in whispers to his troops for a few minutes and then addressed us. He assured us that he and his soldiers were only interested in fighting the Bolsheviks and had never intended to harm the Jews. Now that they had rested they would be on their way to the front to fight for the liberation of the Ukraine. He thanked us for the present and after shaking hands with each of us told us to proceed by way of Murovani–Kirilowzi and Dunaievitzi to Kamenetz–Podolsk. This way we would avoid Bolshevik patrols. We hoped for the best for the Jews of Mohilev–Podolsk and left the Tutunick band.

Toward evening, Professor Friedlander stopped the car; it was time for the evening prayers (Mincha–Maariv). He said them quietly facing the East. Regardless of the religious feelings, the rest of us, even the Polish chauffeur were grateful to Friedlander for praying. We were unsure whom we might encounter on our way.

We stopped in Murovani–Kurilowtzi where the scars of war and pogroms were visible in the shabby clothing worn by the Jews but mainly on the faces of the people. The entire town came with the local committee – they cried with joy that American Jews had not forgotten them: “if only we could all go with you to America now”…

We travelled in the darkness and quiet of the summer night not betraying the dangers lurking only miles away. People were being killed on both sides in a civil war: Jews were listening in the stillness of the night afraid that another pogrom might break out. We travelled without any incidents until we arrived in Kamenetz–Podolsk, not

[Page 74]

suspecting that before another night would arrive, one of us would be dead.

Before I went to my home, Professor Friedlander told me that I should be ready to leave with him for America. My feeble excuses that it was hard in such times to leave the family and that I had wanted to finish my education or that I had to publish my book about the pogroms, the Professor brushed this aside reminding me that any Jew in Murovani–Kurilowitzi or anywhere else in the Ukraine would be happy to change places with me. I rushed home to get ready to leave for America and to be with the family for the last few hours of that night.

In the morning, I learned that another American; Dr. Cantor had arrived with money for the local relief committee and with instructions for the delegation of the J.D.C. to return at once to Warsaw. Information at the Warsaw office of the J.D.C. had it that the Petliura army would not be able to hold out much longer and that the Red Army was ready for an advance into Poland.

I said good–by to my family and to many friends who had come oi wish me god–speed on my trip to America. I hurried to the home of Kleiderman where the Americans were staying. Professor Friedlander was in good spirits, he even told me not to worry about my book and that he would help me publish it in Yiddish and English; he would see that I finished my education in engineering and for the fall he would take me along to Palestine for a visit.

It was decided that the delegation would split: one car with Professor Friedlander and Dr. Cantor would leave at one by way of Gusatin and the rest of us would follow in another car as soon as we had finished our visit to the War Ministry.

The War Minister was at the front and the General in charge immediately asked us to come to his office. Instead of Yiddish, usually used between us, Mr. Kass spoke in Russian and I translated into Ukrainian. The General assured

[Page 75]

us that the situation was not as critical as the Poles would like to paint. He was positive that there would not be any further retreats. He assured us that there would not be any pogroms because Petliura had sentenced a number of anti–Jewish agitators to be shot.

Mr. Kass was very emphatic in explaining that the American and European public opinion would not accept the Ukrainian explanations. It was not infiltrated Bolsheviks who had made pogroms. The Americans now saw the results of pogroms and had learned on the spot the true facts. In the middle of our conversation an officer came in and whispered something to the general. The General vividly shaken told us that he had received very sad news. A Red Army patrol had ambushed and killed Professor Friedlander and Dr. Cantor near the town of Yarmolinetz. The patrol of the Buddeny calvary did not pay attention to the American flag or the J.D.C. uniforms which were unlike the Ukrainian or Polish. The Polish chauffer was seen running into the woods. The Jews of Yarmolinetz brought the bodies to town for burial. The General assured us that there was no imminent danger for Kamenetz–Podolsk because the main force of the Red Army was being pushed back; only isolated patrols slipped through the Ukrainian lines. Nevertheless, he advised us to leave by way of Orinin to Galicia. There we met the chauffeur of the Friedlander car who told us in detail how Professor Friedlander and Dr. Cantor were assassinated in the morning of July 5th, 1920.

We proceeded to Warsaw. There, Dr. Leff was given another assignment by the local office. Mr. Kass went to Sweden to try to get permission to enter the Ukraine by way of Moscow and I left for Paris and New York. I had the sad mission of describing to the widow and her children of the late Professor Friedlander, giving details of the last few weeks of his life when I had travelled with the Professor in the Ukraine up until the fateful July 5, 1920 when he was brutally assassinated.

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Kamyanets Podilskyy, Ukraine

Kamyanets Podilskyy, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 5 Mar 2016 by MGH