|

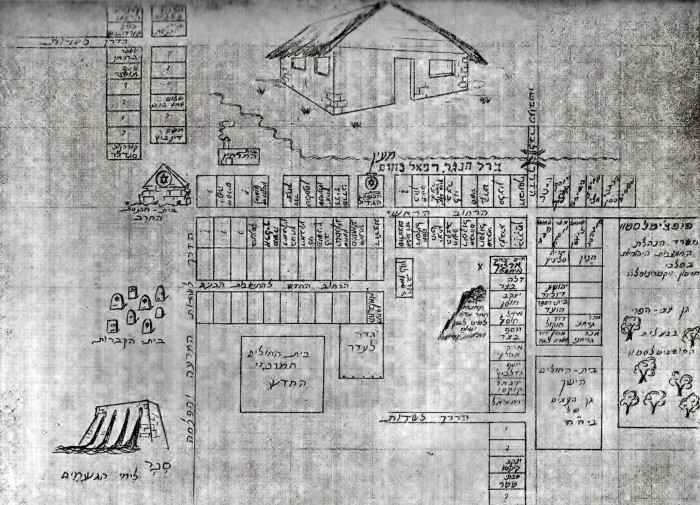

(drawn from memory by Israel Betzer)

|

|

[Page 267]

(Nagartava, Ukraine)

47°18' 32°51'

by Israel Betzer, Yehudit Guzman, Nesya Avidov, Khaia Berkin, Atara and Nakhman Parag, Yehoshua Dukhin,

A Gurevitz, Leah Palkov-Lev, Itah Hurvitz, Moshe Yevzori-Yevzorikhin, Yehudit Simkhoni and Yehuda Yevzori

Translated by Moshe Kutten

Edited by Yocheved Klausner

In a narrow valley, about 300-400 meters from a bald, rocky and steep mountain, which served as a source for building stones, a small spring gushes, its water flowing into the Wysun River. In the winter, the water is rising up to a width of 15-20 meters and then freezes. In the spring, during the days of the snowmelt, the river flows rowdily and sweeps everything in its way.

The authorities brought Jewish settlers, the founders of the colony, to the southern bank of the river. A large Christian village, by the name of Pasad Brezneguvatoye was located on the opposite side of the river. Another Christian village that was located near the river was called Dobro, named after the spring, and the Jewish colony was called Nahar-Tov Ha'Gdola [The Greater Nahar – Tov, literally The Greater Good River].

The spring was located south-west of the colony, within its land, and only the members of the colony drew water from it. Further away from that, on the stream's edge, behind the main street of the colony, opposite to the large synagogue, another stream whose water was good for drinking and laundry, ran; however, its banks were very steep, and it was not possible to approach it with a wagon. Therefore, only the members of the families who lived on the street close to the spring and who could not travel with a wagon to the big spring drew water from it in pails, which they carried on their shoulders, with a yoke.

During the 1890's, the days of the colony's third generation, all the farmers' yards had wells in them, which the farmers had dug for themselves, with a depth of between 6-8 meters. The water in these wells was not good for drinking, therefore all of the farmers continued to haul water for drinking and laundry from the spring, and the water from the wells were only used for the needs of the farm – watering the horses and the cows, washing the dishes and similar uses.

At the end of 1904, when I left the colony, the farmers still hauled drinking water from the big spring and with a yoke on their shoulders from the other spring.

Hundred families founded the colony; each received 40 disiyatins of land (one disiyatin – 12 dunams [or 2.7 acres]). The settlers were not farmers by birth, and many did not even wish to become farmers. The Czar's government was the one that wanted to make them and other Jews into a productive element of society. The compulsory army service and the expulsion from the cities drove these Jews away from their cities and towns to the remote and desolate southern prairies where the Czar's government provided them with large plots and supported them with some meager sums. On the other hand, the government forbade them from engaging in trade or other occupations and allowed them only to work in occupations related to agriculture, such as construction, carpentry or blacksmithing. The adaptation of the settlers to the

[Page 268]

life of working the land was taxing, and their economic state was dreadful. They were not able to cultivate all of the areas allocated to them, and therefore did not have enough sustenance to pay even the minimal taxes for the land. The land was leased to them and their descendants permanently, without allowing them the right to sell or bestow it to anybody, including relatives whose surname was different from theirs. A farmer, who did not have any sons but only daughters, could bequeath the land to one of his sons-in-law, with the government's permission.

During the first generation of the settlers, a quarter of the colony's area which was the farthest from the colony was dedicated as an “area available for leasing” (ovruchnoy uchastok). That area was leased, by public auction according to the law, to the big estate owners for a period of five years, which enabled the settlers-farmers to pay the land-taxes on the leased land and on the land they cultivated by themselves. During the first 25 years, ten families left Nahar-Tov, returned to the city and found sustenance there, some in trade and some in tailoring or similar crafts. The government did not expropriate the ten units (300 disiyatins) but left it as public land, which was leased for two or three years in a public auction, with a full right of the families who had left, or their sons, to return, receive back the land and cultivate it.

I recall that one day during the year 1900-1901, a young man about 25-28 years old, appeared in Nahar-Tov. He was the grandson of one of the farmers who left the colony. The young man came from Odessa or Nikolayev, and demanded the ochastok (land unit) of his grandfather. The process of transferring the land to him did not take long and three to four months later, the young man brought his family and started to cultivate the land. He was absorbed nicely in the colony. In another case, a Jewish person, about 45 years old, has married a good homemaker and had two daughters, one of whom was at marriage age and another was a mature girl, both worked as seamstresses in the city. The family was very pleasant and wished to return to their ancestors' land. They rented a temporary apartment in Nahar-Tov and started the formal process of getting the land. However, the process took too long, and at the end, they did not achieve what they wished for and, heartbroken, they had to return to the city.

During the days of the second generation, some of the settlers rose to a level where they could compete in the public auction, and win a leased area for five years. After leasing a plot the area was never taken away from them and their descendants, according to a new arrangement of dividing the colony's land, which we called an “agrarian reform.”

At the end of the 19th century and beginning of the twentieth century, young work-force was added to the colony – the members of the third generation who were already adapted to working the land. At that time, there were some farmers who managed to consolidate their farms, particularly those who had families with many children who added many available working hands to the farm. The problem was that some of these families did not have sufficient land. At the same time, many settlers still did not adapt to the life of working the land

[Page 269]

and lived in poverty and privation. Among them were those whose father was the only son who received the whole unit of land (30 disiyatins) from his father, and they were also the only sons to their father who owned the whole unit. These people did not establish a farm and owned only a wagon and a pair of wretched horses, and they worked in all sorts of jobs related to wagon hauling. They leased their fields to a Jewish or gentile farmer from a neighboring village for a portion of the harvest (1/3 or 2/5 of the harvest). Because of that situation, Jews haters criticized the settlers and demanded that the authorities confiscate the land from any Jewish settler who did not cultivate his field, and hand it over to landless Pravoslav Christian farmers. I recall that in the winter of 1890-91, a delegation consisting of two officials nominated on behalf of the authorities, came to inspect the farmers' yards. They passed from one yard to the other to inspect the agricultural tools, and they found organized farms, with more agricultural tools than in many of the farms of the neighboring Christian village. Although they did find some poor farms, the colony passed the inspection. During the time that the delegation passed from one yard to another to inspect the agricultural tools and look at the structure of the farms, a diligent group of youths was active behind the yards and supplied the needed tools to yards that lacked them.

The inspection awoke some gloomy thoughts and fears among the farmers who worried about the fate of the colony and its future. It was decided, by the general assembly of the colony, that even farmers who lacked means should make the effort to cultivate their land by themselves, and those who could not do it, would only be allowed to lease their fields to members of the colony. That decision raised the anger of the Christian farmers from the neighboring village, who already cultivated many land areas in Nahar-Tov. One of them said: “If I meet the head of the colony's committee in the fields, I would take out his intestines with a pitchfork”. The word got out to the head of the colony's committee, and he did not wait for long and showed up at that man's field while the man was piling his harvested crop. He entered into a friendly discussion with him, as a long-time friend and acquaintance and said: “I heard that you are angry about our decision concerning the leasing of land in Nahar –Tov, and I would like to talk to you about it, perhaps you would change your mind. You are, after all, a farmer who sustains himself by working the land. If you do not have land, you can lease land by paying for it. There are landless people among us as well. However, as Jews, the law forbids us from leasing land outside of our colony. We are not allowed to lease from the public land of other Jewish colonies, such as Sdeh-Menukha, Bobrovy-Kut or Yefeh-Nahar either. You are allowed the lease lands there, but we are forbidden of doing that. What is your opinion about that? Who should have a priority on leasing available land in Nahar-Tov, you or us?” The gentile was persuaded and he kept it in his heart. During May-June of 1889, when pogroms erupted against the Jews, that gentile came to the head of the committee and told him: “They would not touch your house. I would come to keep guard”.

During the first week of June 1889, rumors were spread that pogroms would take place against the Jews in Pasad Berzneguvatoye where Jewish merchants competed with Christian ones.

[Page 270]

The Christian merchants openly incited the villagers for pogroms against the Jewish merchants in Berezneguvate and in Nahar-Tov. As usual, there was nobody around to turn for help. The police minister (pristav) disappeared. During Friday, the market day in Berzneguvatoye, when the farmers from the neighboring villages passed through the main street of the colony, in wagons and on foot on their way to the market, they gazed into the houses and yards as if saying: “We will visit you today”. As early as before noon, groups of 4-5 farmers from the neighboring village started to barge into the colony through the bridge, pretending to be drunk, and asked to give them liquor. The head of the colony's committee sent them back, every time, by convincing and preaching to them to behave like good neighbors.

During the afternoon, crowds of the village people began to cover the steep mountain across the river, opposite to the colony. They were dressed with holiday clothing like on Sunday. From the mountain, one could see everything of what was happenings in the street and yards of the colony like on the observer's palm of the hand. The colony members realized that they would not be able to resist the rowdy crowd without the assistance of the authority. They decided to act according to the phrase: “…and ye shall watch yourselves…” [Deuteronomy 4:15]. The entire colony flocked to the yard of the “popuchislestvo” (the administrative office of the colonies) near the fruit trees orchard, where they found shelter. The colony emptied before dusk. The families of Rebosnikov and Samuilov escaped to a farm about 12 kilometers away from the colony. They found a shelter in a hut and hid there through Friday night and Shabbat. Only the head of the colony's committee remained in the colony to guard the street from his yard. Upon sunset, the crowd began to glide down the mountain and storm into the colony like ants. The head of the committee came down to the edge of his plot and fired a shot at the crowd, which was only armed with primitive hacking tools. When the crowd heard the shot, they retreated to their village. As the head of the committee was coming out to the street from his yard, the priest just happened to show up in front of him, riding on a carriage, and asked excitedly: “Who fired a shot? This angers the crowd.” However, the head of the committee was not obliged to confess to the priest… They each returned to their place, the priest to his crowd of believers and the head of the committee to his community.

Upon dark, a pogrom started against the Jewish products and grocery stores in the Christian village. The rioters broke the steel doors and the windows, looted products and grocery items and loaded sacks and packages of goods on wagons. Whatever they did not take, they trampled with their feet and burned inside the shops and in the streets. They hid the looted goods in hideouts in the village, neighboring quarry and neighboring villages. The noise of the crowd and the movement of the wagons in the village could be heard from faraway distances, until a very late hour of the night. Later on, they broke through to the colony. They did it carefully and not noisily, but executed their pogrom faithfully. They broke windows and doors in all of the houses, tore pillows and feather covers and robbed things that they were interested in. However, they did not take out much property from the farmers' houses and did not even break one window at the house of the head of the committee.

At midnight, when quiet descended, several Jewish farmers came out to visit the yards and houses.

[Page 271]

The farmers from the neighboring villages gathered on Shabbat morning, intoxicated by their success from the night before. When they saw that the authorities did not intervene they attempted to attack the colony of Romanovka, which was located about 15 kilometers away from Nahar-Tov and being surrounded by Christian villages was isolated. After a week of fear, the Jews in Romanovka gathered all in the synagogue, ready for any calamity. When they sensed that the crowd was approaching, they all went outside of the colony, including the children and the elderly, to face the arriving rioters. They did not fear of desecrating the Shabbat, basing their action on the verse [Psalms (119:126): ”It is time to work for the Lord, for your law has been broken” [It is time to act when the wicked are breaking the commandments]. They came out with sticks, pitchforks, firefighting equipment and other tools that could cause harm, and taught the gentiles a lesson. Ashamed, the villagers retreated from the “Zhyds” and returned to their village empty-handed, with broken legs, injured heads and bloody faces, injuries which the Jews of Romanovka managed to inflict. After that Shabbat, the government woke up and began to investigate what the villagers caused to the area's Jews. The officials went from one village to the other, gathered public assemblies and lectured to the rioters. The police wrote some reports, and with that, they closed the book.

Following the pogroms, the Jewish merchants from Berzneguvatoye and members of Nahar-Tov organized, hired two of the most famous Jewish lawyers in Russia (one of them was the famous lawyer Gruzenberg [who appeared in the Beilis trial) and sued the rioters and the Christian merchants, who incited to riots. The trial was held in the city of Nikolayev and its echoes reached the Jewish and Russian newspapers. The inciters were sentenced to a term of 20 months in jail with hard work, each. The Jews were fortunate to see them jailed and head-shaven. The rioters were sentenced to one-year imprisonment with hard work.

The colony had a committee, which was elected by the general assembly, and its office was officially called the “prikaz” [command in Russian]. The colony's secretary and the committee janitor were located there. The janitor was available to perform all sorts of errands: sending messages, announcements or warnings to the farmers, calling for a gathering, performing any public work and the like. The “Schultz” (the head of the committee), was also sitting in his office every day, if he was not busy doing other public work. During the general assembly, the members of the committee would bring and explain issues, and sometimes would bring forward a proposal. Every discussion in the general assembly was followed by a vote (done by raising hands), the secretary would read the minutes and the results of the vote and the assembly had to approve the proposal with a signature by everyone, without any exception, even those who voted against it. The “Schultz” would approve the resolution with his signature and so would the members of the committee.

The central management of all the colonies nominated regional officials, one official for each 4-5 colonies. Their role was similar to the role of a social counselor. The official responsible for our region was a man by the name of Kessler, a tall man of about forty years of age, with a dignified appearance and everybody respected him. His permanent residence was

[Page 272]

in the colony of Yefeh-Nahar. He appeared in every colony in the region under his responsibility, several times a year, to see if things are conducted properly, check the minutes of the committee meetings and those of the general assembly, and investigate whether the resolutions have been carried out.

*

At the end of the 19th century, the JCA organization [Jewish Colonization Association] started to take interest in the Jewish colonies in Kherson and Yekaterinolsav and provided loans with low interest for two or three years to people who lacked means. Agronomists and officials began to visit the colonies on behalf of JCA. I remember the names of Halperin, Mirkin and Loversky (who later became the principal of the agricultural school established in the colony of Novo-Poltavka). Under JCA's initiative and help, trial fields for new crops were allocated, such as soy and corn for seeds. The fields produced good harvests, and the farmers began to sow the seeds in their own fields. JCA also introduced fruit-tree orchards and vineyards. However, the fundamental problem of lack of land remained unsolved.

After many discussions in local gatherings within the colonies and in regional conferences, the colonies made a decision to demand from the government, that all of the “lands for lease” and public lands, which were considered temporary “leased lands” be returned to the colonies. They requested that the ownership of farmers who cultivated their land (three generations) would be revoked and that the land would be reallocated among the farmers according to the number of males in each family. The colony people turned to the central management of the colonies situated in Nahar-Tov and to General Simov, who was the patron of the colonies on behalf of the government, and who guarded their interests (in the colonies he was named “the loyal devoted father of the colonies”). According to the law, the colonies belonged to the Interior Ministry. General Simov recommended to the ministry to accept a delegation from the colonies, which would request to change the allocation of the land among the farmers. The positive response from the Interior Ministry was swift, and a three-member delegation, two of whom were residents of Nahar-Tov and one from the colony of Novo-Poltavlka, was elected.

The delegation travelled to St. Petersburg and stayed there for 8-10 days. They found a sympathetic audience in the Interior-Ministry and returned home with the good news that the ministry approved the entire plan. A group of 9-11 members headed by a surveyor went out to all the colonies, as early as the same summer (1902) and completed the entire division (parceling) in 10-12 days, according to maps which were prepared in advance. I was fortunate to be a member

[Page 273]

of the group in Nahar-Tov. As an 18 years old, I was the youngest in the group, the rest of the members were all 30-35 years old. This was a pioneering group, which ushered a new period in the life of the colony. Following that group, another committee, consisting of people from among the community elders was elected. These elders knew very well every inch of the land. That committee conducted many meetings. It toured and substantially checked the new parcels (plots) and adjusted the allocation based on quality, topographic location, distance from the house, the roads that lead to the fields and similar factors.

The colony breathed a sigh of relief when, as part of this plan, it received an additional allocation of 25% of its land. Every male son (even as young as one day old), was allocated a private plot of 3 ¼ - 3 ½ disiyatin as a permanent lease to him and his descendants.

Not in every colony the allocation was equal, since the ratio between the male population and the available area was different. Many farms, particularly of those families that had many sons, developed nicely after the parceling and their owners were satisfied. However, that solution was not a radical solution for those families who lacked sufficient land. Many farmers had to look for a side income. Despite that, there was no mass influx from the villages to the city. People knew that those people, who had left the colonies during the 60-70 years since they were founded, found neither happiness nor wealth in the city. Most of them were forgotten, except two, whom the second and the third generations knew very well, although they did not have the chance see them face to face. These two were the poets Shimon Frugg from the colony of Bobrovy-Kut and M. Tz. Maneh from Nahar-Tov Ha'Gdola who wrote the following poem at the time:

Where are you, where are you - the holy land

My spirt is yearning for you

If only you, and me together

Come to life again.

*

At the end of 1904, when the Russia-Japan war broke out and all of the young men were recruited to the front at Port Arthur, the Jewish immigration to Argentina began. According to the agreement with JCA, the Russian government allowed Jewish families to immigrate to Argentina and settle on JCA's land there. They even allowed families, whose sons who were of the age of enlistment, to leave, provided they notified the authorities about their wish to immigrate during May of that year, half a year before the date of enlistment. They were allowed to leave Russia with their families, without the right to ever return. During that year, several families left the colonies of Nahar-Tov, Romanovka, Dubrovna and Novo-Poltavka to settle in Argentina on JCA land. That was just the first group. In later years (1905-1907) many additional families from the colonies left to settle in Argentina.

[Page 274]

During 1953 – 1954, I visited Argentina to see my relatives and the members of the colonies who immigrated there 48-49 years before. I found that only a few elderly people were still alive. Their children and grandchildren left the settlements and moved to cities and towns, where they worked in trade, craftsmanship, textile factories and printing houses, construction materials and various other professions. The Zionist activists were mostly descendants of members of the JCA colonies. Many of the grandchildren of the first Argentina settlers are now in Israel - in the labor movement's settlements, border settlements and IDF.

Not a long time after that, chaos took hold of Russia – the Revolution, Civil War, robbery and murder by Denikin and Petliura [“Whites” leaders] and later on, the new arrangement, which was introduced by the new authorities. In the Jewish colonies, a new regime was introduced and new division between the more affluent farmers (kulaks) and those who were unsettled. The management of the affairs in the colonies was handed over to the poor farmers. The destruction of the colonies began then; the Second World War and Hitler annihilated them entirely. Some of the colonies were not destroyed and only their Jewish residents were murdered.

Recently, I received news from people who immigrated to Israel from Russia who were once residents (not farmers) in the colony of Bobrovy-Kut. When the Nazis conducted the killing of the Jews, they managed to escape from the colony, and went through the “Seven Departments of Hell” in greater Russia. They said that they visited Bobrovy-Kut three years before and saw that the colony was settled by Christians. There were there only a few Jewish survivors, who had returned to the colony. They said that they did not know anything about the rest of the colonies and their Jews.

Israel Betzer (Nahalal)

[Page 275]

Like most of the Jewish colonies in Lesser Russia [Ukraine], my native colony, Nahar-Tov, was actually like a chain of colonies – the Old Nahar-Tov, Nahar-Tov Ha'Gdola [Greater Nahar-Tov], and the New Nahar-Tov and they were all called by a single name. This is unlike Sdeh Menukha, which also consisted of a chain of colonies but with different names. Outside the colony, like an extension of the chain, was the Russian village of Berzneguvatoye whose population was mixed but was mostly Russian. There were other Russian villages a short distance away, around the River Wysun. There was a positive aspect to the closeness to the Russian rural population – the government built an organized regional hospital opposite the center of Nahar-Tov, which served the entire population of the region. Large fairs took place three or four times a year, and big markets were held three times a week. There were also several big shops, of all kinds, in the neighboring Russian village. However, there was also a disadvantage to this closeness, since anti-Semitism erupted from it following every change in the country's atmosphere. I felt that well, almost from my days in the cradle. In 1905, rioters gathered to start a pogrom, but were scattered away before they managed to rob much.

The relatives and acquaintances from the neighboring colonies, who came to the fairs, hospital or big shops, were our guests. From discussions we had with them, I knew about the confiscating of leased land from wealthy Jews, murders, barn arsons, and thefts. The topic of self-defense was a major subject of the discussions. A guard would walk around the colony, every night. He would announce his alertness by knocking with a hammer. People in the colony took turns in serving as guard.

I recall evenings when friends of my elder brothers and sisters would gather, and one of them would read in Yiddish, from the writings of Shalom Aleikhem or Mendeleh Mokher Sfarim. All of the children, young and old listened to the readings with pleasure, open-mouthed, until midnight.

People exchanged whispers about revolutionaries. I recall a young youth, the same age as my brother, who worked as an apprentice for a tailor in the city, and whom people were pointing at as a revolutionist. The police, who came to look for him, encircled a house of one of the colony people, a poor and stuttering man, also a tailor, who was far from any revolution affairs. He was imprisoned and was sentenced to four years of hard labor. In the meantime, the suspect himself escaped leaving no traces.

There was a four-year elementary school in the colony. The students and the teachers were all Jewish and the language of study was Russian. Teaching Torah to the children and youths

[Page 276]

took a higher priority over general education. Most of the children in the colony studied in a “kheder”. In the neighboring village, there was also a four-year municipal school, where most of the children were Russians. In a later period, an evening high school was also established there. When I studied there, I felt the neighborhood's hostility. Young children threw rocks at me and accompanied me with the calls – “Zhydovka”. When the Revolution erupted, the activity of the Zionist movement strengthened and I joined it.

The main agricultural sector in our colony was grain crops. Some of the grain was allocated for the house needs during the entire year and for farm animal feed. The rest was sold to merchants at the train station. Side sectors were growing of farm horses, cattle, geese and chickens. The work tools were plows, sowing machine, and harrows, which were considered sophisticated during those days. They used horses to move the machines. Sowing of the summer crops started just after Purim. Only men worked in plowing and sowing in the distanced fields; however, there also was plenty of work left for those who remained in the farm. They were busy preparing firewood, repairing structures, re-plastering and whitewashing the house. In the spring we sowed summer wheat, rye, oat, corn, flax and sunflowers, and at the end of the sowing season – watermelons, melons and cucumbers. Before gathering the summer or the winter crops, we would take out the dried firewood from the barn, clean it and prepare it for the threshing. The most difficult season was the harvest season, when we required many working hands. Everybody went out to the fields, including young hired workers from the neighboring villages.

We had two harvesters in our farm, each harnessed to horses. Two people worked with each harvester, one drove the horses and the other gathered the harvested crop in small piles. Three or four people followed the harvester, and piled the harvested crop onto big piles, according to the height of the crop stalks. We would leave for the field every week and come back home for Shabbat. One person, riding a wagon with a pair of horses, would bring a barrel of water from the spring and food for the workers every day. We slept in our clothes, on the harvested straw around the wagon, while a primitive tent served as a roof on our heads. We would start the harvest before sunrise and finish after sunset. We cooked dinner inside a big pot, hanged on the edge of a wagon's plough shaft. Sometimes, the wind disrupted the cooking and it lasted longer. On these occasions, I would be tired and fall asleep without eating.

The harvest lasted for three weeks. At the end of the harvest, we would immediately assemble the large wagons and began transporting and threshing the crops. They would wake us up at half past two or three o'clock at night to transport the crop. The field was far away and we had to return with a loaded wagon before breakfast, for the work to progress at a quick pace. The most difficult part of the threshing was separating the grains from the chaff. The wheel of the winnowing machine was operated by hand

[Page 277]

and the dust generated was substantial. When the threshing was completed, the fields had to be prepared again for the autumn sowing.

This cycle of the agriculture seasons continued uninterruptedly until the break of the First World War. The men were recruited to the army, the workload and the grief of the separation weighted down on us. The farm deteriorated continually. Upon the outbreak of the Revolution, the gangs or the government confiscated all of the harvests. I began to think about making Aliya to Eretz Israel by then. My first attempts did not succeed and I was arrested twice. I worked in agricultural Kibbutz training camps in Tel-Khai in Crimea and in Leningrad, before I finally made Aliya in 1929.

We were four sisters who made Aliya, however, not in the same way or at the same time. In Israel, we all turned to the labor settlements, either a kibbutz or a moshav. I participated in the Haganah [Jewish defense paramilitary force during the British mandate in Eretz Israel]. I established a home and a small family. My son is a graduate of the agricultural department in Rekhovot [University]. My four brothers, who stayed in Russia, perished during the war and in the Holocaust.

Yehudit Guzman (Kfar Avikhail)

A lot can be written about my native colony – Nahar-Tov in the Kherson Province. However, it is my wish to point at one of the contributions of my native colony to the state of Israel. My large family – father, mother and nine sons and daughters, was uprooted from its native land, which was cultivated and loved by four generations, and replanted anew in our motherland. We are proud of the fact that all of us are continuing the tradition of working the land, in Israel – in Nahalal, Kfar Yehoshua, Kfar Vitkin and Ein Kharod. We do not have even one city dweller among us. The entire new generation also resides in moshavim and kibuttizim. The nine sons and daughters of my father's home produced 31 grandchildren and 36 great grandchildren, and all of them together numbered as many as the house of Jacob who went to Egypt.

At the beginning of the 20th century, during my distanced childhood, our situation, like the situation of all the farmers in the Jewish colonies was very difficult. However, with time, along with the progress of agriculture in general, and with the maturing of the members of the family, the farm developed progressively. We had eight milking cows in the cowshed and we owned four horses for the field cultivation work. During the winter months – the dead season in the fields – my father and my elder brothers went out to work outside of the colony. We enlarged the house as the family grew; however, it always remained a village house. Its roof was covered with straw, and the floor with clay. Once a week, on the eve of Shabbat, we covered and plastered it with a sticky material.

During the summertime, work was on fire – harvesting and piling, hauling and threshing, separating

[Page 278]

between the seeds and the chaff and dust with the winnower, filling up the sacks and hauling them to the nearby city for sale, and grinding the flour. Father and the sons were the main workers in the field; however, we - the girls – helped as well, piling the crops into piles and rotating the winnower. My parents used to pamper me – the elder daughter. When I was a young girl I liked this pampering, however, when I grew up I participated in all of the tasks.

The days of the summer were characterized by waking up, eating in a hurry, moving around in the yard, neighing of horses when they were leaving or coming into the yard, dust and sweat. The winter season brought respite, peace of mind, long and deep sleep, pleasure of being able to read a book in bed, gathering of girls and boys on the verge of adolescence while being entertained by jokes and laughter and stories and sometimes by having one of the group's member read a book aloud. That does not mean that we did not work in the winter. In the wintertime, we still had to feed and milk the cows, bake, do laundry, fix clothing, sew and do various other works, which were performed during the cold and the snow. However, the days were shorter and the nights – longer, which allowed for more sleep and rest, reading a book and entertaining together. Sometimes we used to go out to freshen ourselves in the shining snow, which was creaking under our feet, and play pleasurably.

Our basic education was based on a four-year elementary school. We did possess a strong desire for additional knowledge, to study and widen our horizon. However, the gates to the high schools were closed for us, due to the “numerus clausus” – the law limiting the number of Jewish students. Only the sons and daughters of wealthy people managed, somehow, to get into the high schools. The colonies' youths who wished to obtain a high school education had to study as externs. Only when the Revolution started, in 1917, the limitations were removed and many of the youths in the colonies made plans to enroll in the various schools and I wished to study medicine. However, the events that took place disrupted many plans, mine included. The Revolution's storm that raved with enormous forces, wiped out everything that existed in order to build a new world.

A group of inspiring youths, organized to make Aliya to Eretz Israel and build there a new life, came to us to receive agricultural training. They lived with the farmers, and accompanied them or their sons, who trained them how to plow, sow and harvest. These young men brought with them a new spirit into the colony. Some of them spoke Hebrew and they taught us the language as well as songs in Hebrew. They infected us with their enthusiasm, and many of the youths began to feel that their place was in Eretz Israel. Being agriculturists from birth, it would be easier for us to continue working the land and living a village life in Eretz Israel. We dreamt about being able to build and establish a new Jewish life there.

The girls in the colonies were not engaged in enhancing their appearance. I did not own any ornament or jewelry. My Shabbat shoes were not high-heeled or sharp-nosed and were not made of good leather either. My dress was made from simple material –

[Page 279]

with red flowers on a blue background. I was very proud about my shirt, which I embroidered with my own hands during the winter nights.

One day in the summer, I was working piling up hay, and one of the young pioneers, who came to us for training, worked with me. The sun was hot, and my tanned face was dripping with sweat. I wrapped my hair with a kerchief. My dress – a fading work dress, had a big patch and another small one on the left sleeve. I wore open sandals on my feet. The young man worked vigorously. All of a sudden he stuck his pitchfork in the hay pile, sipped water from the jar, wiped his sweat with his sleeve and stood in front of me, reviewing me with a big smile and muttered admirably toward me: “A sheineh shikseh” [a nice gentile girl. “Shikseh” - a term usually used in a derogatory way, but sometimes with affectionate intent]. My heart was beating from excitement. I was touched by that compliment. My self-confidence about my looks was strengthened.

I deviated from the main story, but this is a typical older women's weakness – to recall with pleasure and pride any complement they had heard during their youth.

I will end the way I began – our family lived and worked in the Kherson's colony for four or five generations. All of my brothers and sisters continue with the village way of life and work the land here in Israel. I am proud of the fact that my elder son is a member in moshav Nahalal. My younger son is in moshav Nir Banim and my daughter in moshav Ganei Yehuda.

Nesya Avidov (Nahalal]

I was born in an agricultural colony in Southern Russia, which carried a Hebrew name - “Nahar Tov”. I absorbed the quiet Jewish village way of life form my childhood. However, in the beginning of my youth I left my village and moved to Kherson, the nearby city. I did not adapt easily to the bustling life in the city. I longed for the village, and wished to breathe the smell of the fields and always dreamt to return to the village life.

When I returned to the village, I met there the lively youths who worked in their farms during the day, and devoted their evenings to activities in the Zionist movement and organized an evening class in Hebrew. Together we devoted ourselves to produce shows in the new theater, and the revenues were contributed to the JNF (Keren Kayemet Le'Israel). We arranged balls where we sold books from the “Kopecko Bibliotec” [A library for pennies], and JNF stamps. We also sold Zionist Shekels [Zionist organization's membership tax]. We transferred all of our revenues to Dr. Bodenheimer [A prominent Zionist leader, an assistant to Dr. Herzl and founder of the JNF] in Cologne. The box [The JNF blue collection box] was not absent even from weddings. They would build a big tent in the bride's yard

[Page 280]

where the “kleizmers” [Yiddish for musicians] of Rabbi Yehuda-Leib and his sons, each with his own instrument, along with “Motl der kleizmer” [Motl the musician] with his fiddle would entertain the crowd. JNF box was the main attraction in the tent.

In July 1914, our family's dream was fulfilled – we made Aliya to Eretz Israel. Only part of the youth in the colonies dared to make Aliya. Many lingered, since nobody expected that a world war would break out and put an end to all the dreams.

Who knows what was left today from the colony, which was so dear to all of us.

Khaya Berkin (Tel Aviv)

Our first experience in the colony, connected with Eretz Israel occurred when we were 7-8 old. While we were in the classroom, two wagons loaded with belongings, people and children were observed travelling towards the train station. We were told that the Berkin family was making Aliya to Eretz Israel. The Zionist activity in those days of the beginning of Zionism was concentrated in selling [Zionist] Shekels and stocks of the Colonial Bank [Later Israel's Bank Leumi] and in procuring Zionist literature and journals. However, in the spring of 1917 and with the national awakening, part of the youth and some additional older adults organized themselves into an association, which was called “Ha'Tkhia” [The Revival]. During that same year, pioneers from the Ukrainian cities of Kremenchug and greater Kiev, as well as from other places, came to us for the first time, to receive agricultural training. They, along with the local Zionists constituted the nucleus for the local branch of [the Zionist movement of] “He'Khalutz” [The Pioneer]. Among them was the activist - Mikhael Kafri z”l, who handled the new arrivals and distributed them among the farmers. Not all of the farmers were excited about taking in a “Khalutznik” [“pioneer”], a young man who came directly from a school bench and did not know what work was. Tender girls, who had just completed high school or just started their studies in a university, also came to us. They tried diligently to become hard workers as well. They all used to gather in the evenings, sing songs about Zion and weave their dream together about building and settling Eretz Israel.

Families would go out together to thin the corn or weed out the sunflowers. Children excelled in these tasks due to their agility. The youth was also involved in tasks associated with the harvest, which was performed by mechanical harvesters harnessed to three horses. Workers from the gentile village would complement us: “How nicely these young Jews are working, as if they are ours”. During the harvest we would rattle ourselves on wagons to the distanced field, still half asleep. We would catch a bit more of a nap under the rattling of the wheels and the jolting wagons' ladders until we arrived

[Page 281]

at the location of the harvest piles. The sun would rise then, and dawn would open our sleepy eye-lashes and work began. An adult would load the crop and a boy or a girl would arrange it on the top of the wagon. We would leave for the field for the entire week and return home only to bring additional food and water in barrels for the people who stayed in the field. We would all return home only for Shabbat, to recover and prepare for another week of work.

The harvest lasted several weeks. During the summer of 1919 or 1920, when gangs were roaming around our area, I would be sent home to bring food for my father and brothers who were harvesting in the field, which was located 10 kilometers away from home. I was only a 13 or 14 years old girl at the time. One evening, when the harvesters stopped their chattering noise, we sat by the wagons, and my father z”l went back to fetch something from home and had not returned yet. The meat, which was being stewed for dinner, was hanging above a small fire on a wagon's shaft. My brother Khaim handled the cooking and we helped him. All of a sudden, we heard shouts, and shots pierced the air. Robbers attacked us. We quickly spilled the soup over the fire and my brother commanded us to hide in the piles of crops, which were scattered around. We did not have any weapon, and my brother Mar'el understood immediately that the robbers intended to rob his beautiful thoroughbred horse. He jumped on the horse, broke his way through and disappeared towards the colony to call for help. My brother succeeded to tie the legs of the rest of the horses to prevent their theft by the bandits, and we all scattered around the crop piles. Many people from the colony, the police and my parents, who were fearful for our fate, arrived at midnight. They did not find us easily, since, despite the fear and the excitement, we all fell asleep, exhausted, inside the piles of crops, while lizards and bugs were crawling on our bodies.

During the year of 1922, the persecution of the Zionist movement began, which forced it to go underground. Until then, large groups of pioneers arrived in the colony for agricultural training, and the local Zionist youths organized themselves in a branch of “He'khalutz”. The first group of pioneers left on its way to steal the border and make Aliya. In 1917, during the short period of freedom, the Zionist organized a bonfire for the celebration of the holiday of Lag Ba'Omer in the colony. This was a beautiful celebration. The schoolchildren chorus, the entire youth and the colony adults, all waving the national flags, went out on foot and wagons, singing songs of Zion, all the way to the fields. At the artificial lake, about 2 kilometers from the colony, a picnic was arranged. The holiday symbolized embracing the nation's past, longing for a future of national independence, and fulfillment of the Zionist dream. This short period of freedom illuminated the later years when the Zionist movement had to operate underground, along with the suffering and the heroism associated with underground operation – wandering on the roads, stealing borders, imprisonments and expulsion.

Following the departure of the first generation of pioneers, the second generation's branches of “He'Khalutz” movement and the “Social-Zionists” were established by the brothers and sisters of those who left. Many who joined the Komsomol [communist youths] followed the youths suspected of being Zionist with apprehension and watched our every step.

[Page 282]

It happened during the year of 1925. We were collecting contributions among the movement's supporters for prisoners and exiled Zionists. I found out that my imprisonment was nearing, and travelled to another colony for a period of time to avoid arrest. I returned at one point, and stayed at home to hide. During one of the evenings, my younger sister, who went to one of the Zionist branch's activities, did not return home. We were informed that the entire group of members who participated in that activity was arrested and there was a fear of impending searches in their homes. I escaped to the neighboring village through a desolate road, as if to visit the home of a farmer – a Ukrainian family friend. I could not stay there for long and I came back through the same road, but did not enter the house. I stayed in the yard and sat down in the barn. My father was at the fields, as that was the period of plowing and sowing of the corn and the sunflowers. The son of my father's partner came from the field to take a barrel of water to the field. I laid down in the wagon by the barrel and covered myself with the tarp that covered the barrel. I was soaked with water from the barrel, from time to time. That was how I traveled to the location of the plowing.

I participated in the plowing work that day. That was the last time I plowed the soil of the foreign land. My father brought me a few items from home, and after sleeping under the Ukrainian sky for the night, my father brought me to the nearest train station. From there I travelled to the large city on the coast [of the Black Sea, Possibly Odessa] where I waited for a few months until the papers were arranged. In the meantime, I continued to be active in the underground Zionist movement. In the fall of that year, I boarded the ship “Lekhon”, which transported 500 passengers to Eretz Israel and two weeks later I began to plow the fields of Ein Kharod in the Jezreel Valley.

Atara and Nakhman Parag (Ein Kharod)

[Page 283]

I was told by the colony elders that the colony was founded 100 years before I was born. During those days, the prairie was covered by tall weeds, above the height of a person, and packs of wolves, which would attack people, used to roam the wild area. People did not dare to enter the tall grass for the fear of wolves. The life conditions were very hard, and people lived in poverty. The bread was made of rye and they would make it very seldom. By the time it was eaten it would be hardened and became stale. No knife could cut it, so they would break it with an ax, and would dip the crumbs in water to be able to eat it. The first settlers performed their work in the field using primitive tools and their horses were fed naturally in the weed forest. The settlers would stay awake at night to guard their horses, but that was hardly helpful as theft was rampant.

In the summer, they all walked barefoot; however, in the wintertime, when they had to wear shoes to get out of the house, only a single person from each family could be outside, since the entire family owned only a single pair of shoes. The houses were rickety and uncomfortable. In the winter, the entire family gathered in the kitchen, which was the only heated place in the house. The kitchens were very crowded in the winter since the families had many children.

During our time, our colony was already very well organized. There was a dairy plant in the colony, where the cheese industry flourished and sent cheese products to the big cities. They would buy cheap work tools and supplies for the money they received. There was no more fallow land available, and land was actually very expensive. There was really a shortage of land.

It is worthwhile to note that even during the most difficult days in the life of the colony, the children continued to study in “kheders” and yeshivas. We had many scholars in our colony. When I asked where they received their broad education, they told me that during the early days

[Page 284]

people used to get married at the young ages of 13-14. Obviously since the young husbands and wives were still children, they could not get along with each other. If the husband was talented, he would run away from home and go to study in Vilna, the city with many Yeshivas. He would sit and study for 10-15 years until emissaries would be sent to bring him back home, to make sure that the wife would not remain agunah [according to a the Jewish Law - a woman bound in marriage by a husband who is missing]. There was also an opposite phenomenon, when people from Lithuania fled to the colony.

When I reached the army's age, I was recruited. That was during First World War. The Czar's army retreated tens of kilometers a day, and the head of the army issued an order to leave behind scorched land. A company of Cossacks' commando was assigned to fulfill the order. The Cossacks would coat the wooden beams of the houses with kerosene and ignite entire villages and towns. The residents would flee in all directions and the Cossacks would use the tumult to rob and murder.

Two and half years later, I came home. The Revolution erupted then, and I did not return to the front. A decree was issued by the government to reallocate the land according to the number of people in the family. The owners of the large parcels did not agree to do so, and disputes and rifts ensued. In the meantime, the Revolution strengthened and the wars between the Whites and the Bolsheviks continued as well. The regime changed hands continuously and large areas went from one side to the other. In the area of the colony, the Ukrainians, who wished to achieve independence and freedom from the Russian rule, were active. The Ukrainian battalions constituted a regular army that was busy performing robbery in addition to warring. Following a few defeats, the Ukrainians stopped fighting and shifted to organized robbery in the entire area.

Due to the rifts and disputes in the colony, no self-defense was organized. The attackers constituted a regular army with modern weaponry, relative to the period, and the members of the colony owned only meager and cold arms. At one time, the robbers entered the colony, took ten hostages and announced that if they do not receive 65,000 Rubles by 11 o'clock the next morning, they would execute the ten hostages and would destroy the colony to its foundation. Messengers were dispatched and they succeeded to obtain secured loans from many places but managed to collect only 40,000 Rubles. That amount was less than what was required. The two gang's soldiers, who came to take the messengers to their command, announced that the amount collected would suffice. On the way to their camp, the escorts robbed the money from the carriers and ran away. The messengers returned to the colony and announced that everybody should take shelter, since the gang would surely appear shortly. People just managed to hide when the soldiers appeared. The property in the colony was looted and the people who were found were murdered. Many houses were destroyed to their foundations. The rioters raged for three straight days and finally left the colony. After the gang left the colony, several youths, including me went out towards the fields where members of the colony hid, to notify them that the rioters had left. However, our calls were not responded to, due to an event that had occurred previously in the neighboring colony of Nahar-Tov Ha'Gdola. Messengers went out on horses to announce that the gang had left, however, the colony people thought that the announcers

[Page 285]

who rode on horses, were the rioters, raised their feet and ran away. The flight also stirred the people of Nahar-Tov Ha'Ktana to run away. Only when everybody returned to the colony the mistake became clear.

After the gang of rioters left the colony, a battalion of the Bolshevik's regular army, which was known from the horrible pogroms it executed in Poland, arrived at the colony. A heavy fear filled the hearts of the residents. The soldiers became insolent hour by hour and everybody fearfully waited for a pogrom to begin. However, things changed entirely by chance. About an hour away from the colony, a conference of the Revolution's leaders took place, where Kamenev, who was at the time one of the prominent Bolshevik leaders, participated. Kamenev gave a speech at the conference, and following his speech, the public was given the opportunity to ask questions. Some of the colony members infiltrated the conference and I remember it in details. Kamenev announced that it was possible to ask questions in writing. Among the written questions the following question was included: “What should we do with the Zhyds?” The question was pushed all the way to the end. When it was presented, the communist leader rose up and announced firmly that whoever would dare to cause harm to a Jewish person – would be held responsible, even if he was an officer. The following morning, the attitude of the gang's members changed from one extreme to the other. They became polite and friendly and did not take anything when they left the colony.

Yehoshua Dokhin (Afikim)

As far as I know, none of the Nahar-Tov's farmers knew precisely when the settlement in the colonies began. I could learn only a little from the colony elders who also received their information from their elders. I was told that the whole area was desolated. Some people told stories about meetings wolves and bears, who took their toll on the sheep herds.

A few Germans settled in every colony along with the Jewish settlers. They told us that the authorities settled them among our ancestors so that they would train them and also in order to prevent from forming villages consisting only of Jews (The colonies were called “settlements of Jews and Germans”). However, as far as I can recall, in our time our people surpassed the Germans in their diligence, and definitely surpassed the Russian farmers. The Jews excelled in introducing methods aimed at making the work more efficient, and they acquired every modern agricultural machine. While the Russian farmers still harvested using sickle and scythe the Jewish farmers used harvesting machines. There was almost no cultural life, except a single public library common to the entire colony, where only a few visited. During the revolutionary years, any person who visited the library was suspect of being a revolutionist. The attitude of the farmers toward anybody who was against the monarchy was hostile. Some of the farmers were also hostile towards the Zionists.

[Page 286]

During my time, there was no Zionist movement in my colony, and as far as I know, not in any other colony. Only a year before the war, a small Zionist club was organized in Nahar-Tov, however, the entire Zionist activity was expressed by a gathering of our group to read about Eretz Israel and dream about it. Only during my last Yom Kippur, I dared to place a bowl in the synagogue for contributions to the JNF [Jewish National Fund]. I did that under the patronage of my uncle who was a “gabai” [synagogue administrator] in the synagogue. Not many dared to think about a journey to Eretz Israel. The youth was so attached to the farm and their family, that even thinking about leaving seemed like an impossible task. Only a few from among the colony members came to Eretz Israel during the years of the Second Aliya [Jewish immigration to Eretz Israel 1904 – 1914].

In 1913, I visited an adjacent colony to say farewell to my relatives there, before my journey to Eretz Israel. I met with the youths there and tried to discuss Zionism with them, but nobody showed any interest. Only during the Revolution years when everything began to fall apart, branches of Zionist movement were created in all of the colonies and part of the youth arrived in Eretz Israel.

A. Gurevitz (Kfar Mal”al)

One of my roles during my distanced childhood was to greet the returning herd. When the sun was setting, I would hurry up along with the other children of my age group – 6-8 years old, to the edge of the colony to greet the cows herd. I would fetch a thick piece of rye bread, covered with spicy garlic spread and salt, game rocks (Tzekhin) and a long stick. We would sit down on the side of the road, and while chewing the bread with a great appetite – we would play with the game-rocks. All of a sudden, a dust cloud would rise - the herd! We would jump on our feet and burst into the dust.

Usually, every cow knew where the stall in the yard of her owner was, and would confidently turn towards the yard by herself, upon approaching it. However, just as it is with people, there were some extraordinary cows that would do things just to get somebody angry. We had a cow like that in our cowshed. Her sisters had been obedient, more or less, and would make their way to the yard with some directing and guidance on my part. However, that rebellious cow was not satisfied with the pasture and the straw and bran portion waiting for her in the yard, and when the herd would approach the colony, she would burst aside and gallop straight into the vegetable gardens of the neighboring Russian village.

[Page 287]

More than she managed to gorge with her mouth, it was her feet that did the damage - crashed, trampled and destroyed. My role was to prevent her from doing that bad feat. I would jump into the herd; my eyes would search for her in the dense dust cloud, and with my long stick and my hoarse shouts I would fight with her like a matador in the bull-fighting arena. She would turn right – I went in front of her, hitting with my stick and yelling: “despicable, stubborn, and imbecile!” Like a creature experienced in planning ploys, she would then turn left, but I was agile and would immediately jump in front of her and hit her in the face. The rest of the cows would progress and go farther, but I would continue to jump right and left with my last drops of energy. Usually I had the upper hand, and after I managed to direct her towards the colony street, she would walk, innocently and scrupulously while I dragged myself behind her with my stick, reminding her, once and a while, that there was law and order and a judge and that she needs to be obedient. When she would enter the inner yard, I would close the gate and would breathe a sigh of relief. It is a pity that I do not have a picture of my face and my appearance in such moments. I looked like coming from a long journey in the desert. Barefooted, with my fading dress, my face doused with a layer of dust and sweat, but my heart jumping from joy. Who else was as victory-happy as I was?

However, there were times when I lost, despite my agility, long stick, and my desperate shouts. The rebel would use a cunning ploy, would twist here and there to surprise me, raise her legs, run away, gallop and burst straight into the vegetable garden where juicy cabbage grew. I would hurry after her with my last drop of strength. When I would arrive in the garden, my eyes would grow dim seeing the destruction she managed to cause. I would look fearfully at the Russian farmer running towards her, trying to drive her away by cruelly hitting her with his pitchfork while his mouth spitting curses towards the cow and the Jews. The following day, the farmer would receive three rubles from my father, as a compensation for the damage. The humiliated and defeated cow, would march, head-down, in the street, and I would follow, breathing heavily. I would be filled with bitterness because of the farmer's curses, humiliated, wretched and covered with a layer of dust and sweat, would drag my feet, heavy like wooden logs, my eyes in tears, with a darkness, as deep as the darkness that descended on the colony, in my heart. When the cow would enter the yard, I would slump down on the stone at the gate, groaning and breathing heavily. My tears would be dried out by then but there was still a bitter dryness in my mouth and in my heart.

Years passed, and childhood experiences were covered with dust; however, when I see a herd of cows returning from the pasture, my heart begins to quiver. Is that because of the shining childhood memory of the experiences of greeting the herd, eating a piece of bread smeared with garlic spread, playing the game of stones on the side of the road, and crying from joy when we jumped into the dust covered herd? Or perhaps this is a result of touching again the scar that this rebellious cow left in my soul?

Our family was not blessed with boys. My sisters and I engaged in many tasks. As the youngest daughter, I was assigned with trivial tasks – greeting the herd, driving away,

[Page 288]

several times a day, the pigs from the neighboring Russian village that they were enchanted by our piles of straw or the potato patch. From time to time I would hear the calls of Mother or one of my sisters:

“Leah, hurry up, the pigs are already burrowing! Run!”The several tens of chicken laid their eggs in one of the corners of the pen; however, just like that rebellious cow, a few chickens that sought solitude laid their eggs in the attic. One could only climb there through a narrow hatch, located at the edge of the roof, and only my small body could pass through it. Once every day or two, my job was to climb up there, reach the hatch, slide in and fetch the eggs. Besides these roles, they would assign me errands to go to the store or to the neighbors. I wanted to play, but I was busy with all sorts of tasks throughout most of the hours of the day.“Leah, the pigs had already destroyed the garden! How did that happen? “

We had a shoemaker as our neighbor. He was also blessed only with daughters like in our family. One of them was my age. I envied her and her sisters being the daughters of a craftsman, who were not tasked with the duties of a farm and were free to roam around and play. Their clothing was always clean and their hair combed. But sometimes, my friend envied me such as when we would climb on the thresher (a device similar to the Arab thresher. It was made of wood, equipped with flint rocks on the bottom. A pair of horses was harnessed to it and they rotated it over the straw to chop, crash, and soften it until it was ready for the teeth of the farm animals). We, the children, would pleasurably sit on the thresher, sometimes just to add weight to it, as the thresher was more efficient, the heavier it was. I am not sure whether the children, who ride on top of wooden horses or on wagons and trains in an amusement park today, enjoy their ride more than I did then. The horses would loop around – gallop like mad over the straw, in a circle. Clouds of dense dust, and thin chaff would envelop me, penetrating my eyes, ears and nose and I would melt with happiness. I felt it all over my body – I was really a princess. My friend, the shoemaker's daughter, would stand on the side, at that time, her face expressing her envy, and her eyes begging me to put her too on the board. How sweet a reparation was that for my envy! …and my joy would surge. Nevertheless, after I had received a full satisfaction, my sense of generosity would suddenly awaken, and I would allow her to come up to my seat. Both of us holding and embracing each other would fly, rejoice, shout from joy and sing.

It would seemingly be possible to claim that my childhood was depressing. There were no kindergarten, no toys and no flowery dresses. Even a red ribbon for the hair was considered a big event. There was certainly no chocolate or fine candy, and in addition to all that – there were those duties – greeting the herd, chasing away the pigs, collecting the eggs and going on errands. However, that claim would be erroneous. Wasn't I happy when I whirled on the thresher? Didn't I enjoy the rye bread smeared with garlic like a kid who enjoys a chocolate? Wasn't I feeling joyful and filled with a sense of triumph when I succeeded in forcing the rebellious cow into the yard without a mishap?

Father would leave on Sunday for the distanced field

[Page 289]

and return on Friday. Sometimes my mother would cook Father's favorite dishes, comb her hair and wear a clean dress. Holding a basket in one hand, and my hand in the other, we would leave for that distanced field. The field was more then 10 kilometers away and it took us two hours to reach it. On the way, we would pass the rainwater reservoir, which served for watering the herds. I remember the beautiful sight of the stalks of grain on both sides and the cemetery surrounded by a tall and mysterious fence. When Father would see us from afar, he would wave to us with his arms, and turn his horses towards the wagon. When he would reach us, he would put some hay for the horses, and the three of us would sit down in the shade of the wagon. Father would eat heartily the Borscht and the dumplings and would throw some compliments to Mother. She would tell him, with charm and a smile, about this and that. I would be running around like a jumpy goat, here and there, and my heart would be filled with happiness and joy of life.

During the harvest season, when I was ten years old, my father used to wake me up at two o'clock at night, in order to travel with him to a distanced field, located 15-20 kilometers away from the village. Still wrapped in my sleep, I would curl up in the stiff wagon, all of my bones in the body aching from the jolting. The sun would rise slowly, and I would take out my books from my bag and immerse myself in reading. Father was priding himself for our nimbleness when we met some Jewish farmers who were late leaving for work. When we would arrive in the field, my father would hand me the bundles of crops and I would stand on the wagon and arrange them. On the way back, it was comforting to cuddle over the bundles of crop.

When the crops were ripening, Father would harness the horses, and we would go out to examine the fields. I would be sitting on the wagon's springy bench, between Father and Mother. The crop stalks would be nice and tall and my parents would be happy. When my father would cut the hay, I would be roaming around in the field to pick red pea and blue star-thistle flowers.

Years passed and I was already a grown girl, carrying the burden of farm work. My elder sisters were married and it was the harvest season. Working with a pitchfork is a task which is hard even for a man. The sun was burning, the sweat dripping, the back hurt, the feet stepped over the chopped stubble. The eyes rose up continuously - is the sun still far from the western horizon? At last, the sun tired as well, and she crawled down and disappeared. Father released the horses from the harness and tied their legs. They walked on the chopped stable, their mouth looking for a forgotten uncut stalk. I hung the pot over the wagon shaft to cook the groats soup in it, and arranged the fire underneath it. At a certain distance away from the wagon under the cover of the evening dimness, I poured a bucket of water on my dusty and sweaty body, put on a clean robe, and made my hair.

Father and I sat on the ground, and had a hearty meal of green cucumbers, onions, eggs and groats soup. Father then spread himself on a pile of crop close to the wagon, and fell immediately into a deep sleep. I stretched over the soft straw inside the wagon. I was, too, tired from the day's work. My eyes were half closed, but my senses were awake though. I fixed my eyes on the heavenly stars. Silence descended over the world, and I felt light like a speck of dust

[Page 290]

in the infinite space. My eyes closed and I was hovering in dreams of an adolescent girl yearning for the future.

It was a late hour. The entire universe was in deep sleep, even the horses. A few stars, older and less romantic, withdrew from the sky décor. All of a sudden, a song of an outpouring soul burst out of me. My eyes were closing, and the sweetness of sleep engulfed me and I was sinking into a world of oblivion. All of a sudden, a burning sensation in my eyes: a ray of a young sun was tickling my eyebrows. My eyes opened lazily. A new day with a new fiery sun, pitchfork, sweat and exhaustion arrived. The horses were already harnessed to the harvester. Father's face was sweaty. Morning tiny flies gathered around the remains of the meal from last night. I quickly jumped off the wagon, joined the other working women and grabbed a pitchfork. It is not good to lose time in the morning when working is done at a relative comfort. I worked vigorously, enjoying my agile progress. The sun was still soft and caressing and the work in that hour was still pleasant. While lifting the pitchfork, a soft and caressing smile would be passing through the edges of my lips when I recalled one of the dreams, which fascinated me during the night.

About fifty years passed since then. I was fortunate to become an agriculturalist in Israel; however, how large is the distance between the past agriculture, difficult, primitive and stingy, and the ample life of the agriculturists today? Today, a cow, even the most rebellious, would not run away from the herd. The chickens would not recluse themselves to lay their eggs in the attic. Farmers do not go out to the field or the orchard for a two-week duration at a time, and not even for a whole day. People rest at home during noontime. They have nice furniture, an electrical refrigerator, an electric washing machine and an electric or gas stove in the house. At the time we did not even use firewood for heating, cooking and baking, since our area was not blessed with many trees. During those days, fire was lit by using bricks made of cow dung. The time difference between that period and today when gas stoves are used, is only one generation.

During the Russian Revolution, tens of young men, “members of the He'Khalutz”, arrived at the colony for agricultural training and ushered in a Zionist atmosphere. Our youth joined the movement as well. We studied Hebrew, and listened to discussions, until the arrests came. They sentenced us to exile in Siberia. We walked for days and months throughout Russia – Kharkov, Samara, Chelyabinsk all the way to Tomsk and Semipalatinsk [Semey]. We waited for assistance from our friends in Eretz Israel. That assistance came after a year, from the Authority for Prisoners of Zion [Prisoner of Zion is a detainee arrested and jailed due to Zionist activity forbidden in his or her country]. I returned from Siberia on a train. The happy group of people who would make Aliya gathered in Odessa. The joy of the people was bitter-sweet due to the sadness of the separation from friends. There was no way for us to know when we would see each other again. On the ship, I was assigned to hide the certificates, which could be used as a proof of our illegal activity and our struggle for the subsistence of the “He'Khalutz” organization. I hid the certificates well in the belt of my dress. All of a sudden, policemen boarded the ship and separated me from my travel companions. A thorough examination commenced from head to toe. My heart pounded from fear, but my treasure was not discovered. With a restrained joy, I joined my fiends…

We finally reached the day when we disembarked on the shore of our motherland.

Leah Palkov-Lev (Kfar Bilu)

[Page 291]

My father inherited his farm from his parents. It was a property of 25 disyatins [67.5 acres] of high quality cropland. During my childhood, we owned very primitive tools for land cultivation; we resided in a shack that protruded from the ground. One had to go several stairs down to enter it. It just had two windows positioned towards the street, and two toward the yard. The shack had a door with a wooden handle, and a rope that was tied to it had to be pulled to open and close it. The roof was covered with straw. About sixty families of farmers resided in the colony. The shape of the houses was uniform and so was the way of life. The borders of the colony were: the Wysun River and a large and beautiful grove in the east, the cultivated and pasture fields in the west and gentile villages - south and north.

We had a very beautiful synagogue in Nahar-Tov, located opposite of our house, with a large hall for weddings. I loved that corner of the colony. Our elementary school and the teachers were Jewish, but the Russian authorities supervised it. Russian teachers participated in our matriculation examinations, and the curriculum was taught in Russian. The school was dear to my heart and I loved it deeply. The education in the school was tuition-free since we were legitimate citizens who paid taxes to the state like all other Russian citizens who worked the land.

Young men from the colonies served in the army from the age of twenty to twenty three. I got to see my colony constructed in a new style – nice houses, with sophisticated tools for cultivation, large herds of milking cows and herds for meat. We owned two pairs of horses for work and leisure, a wagon for transporting the crops form the field and a snow wagon. We received a loan from the JCA under favorable payments, to establish our farm.

During 1917, pioneering youths arrived at our colony from throughout Russia to receive agricultural training. I loved my colony, and my mate was also a native of Nahar-Tov. We built a new farm for ourselves and worked in it together. We were filled with the joy of creation.

However, our idyll vanished very quickly after that. During the years of the Revolution, following the First World War, our colony was destroyed and the entire Jewish folklore was destroyed with it. I, by then without my mate, with three young children left Russia and made Aliya to Eretz Israel. This was in 1925.

Itah Hurvitz (Mikhmoret)

[Page 292]

|

|

| The colony of Nahar Tov (drawn from memory by Israel Betzer) |

[Page 293]

The city of Nikolayev – a bustling and rich city, had a large shipyard and big factories with tens of thousands of permanent workers. The streets and the markets were always filled with people. Among the city rich there were many Jews as well as many Karaites[1] I think that all of the big commerce was in the hands of Jews. There were several synagogues in the city. I even discovered a “Khabad” synagogue with a beautiful sign; however, there was only a meager content in it beyond the sign. I did not like Nikolayev. I did not feel any Jewish life in it, since the Jews constituted an insignificant minority in the city. The workers used to receive the weekly wages and would go shopping and pay debts on Saturdays. That was the reason why only the big wholesalers among the Jews could afford closing their shops on Shabbat; however, almost all of the Jewish shops were open on Shabbat. The vegetable market was full of Jewish women and the same goes for Jewish horse-traders in the horse market. The horse-market was as noisy and crowded on Shabbat as in a weekday.

I visited various synagogues and other places to meet Jews. At one time I would enter into a conversation with an old man and another time with a young one. I also knew teachers and “melamed's” [Jewish religious teachers]. I once met an elderly Jew with a beard who wore a “casquette” hat (a cap with a visor). I assumed that he was not a Jewish city dweller, and started to interrogate him about who he was, and where he was from, until he said that he is from “Dobrinkeh” [Dobroye].

“And where is this Dubrinkeh?” I asked.I told Mr. Schwartz that I saw a Jew, from a Jewish colony, who told me about Jews who work the land there, just like the gentiles. I got this encounter into my head and my heart. I had to go there.“This is a Jewish colony, about fifty versta's [about 33 miles] from Nikolayev”.

“Are you a farmer?”

“And what do you think I am doing? Scribing Teffilin?” he answered with a question.

“I am just asking” – I said. “I have never seen a Jew who really works the land”.

“Then you should come to us and see many Jews who are working the land” – he challenged me.

“What kind of discovery did you make?” asked Mr. Schwartz. I see these Jews every day. They bring grain for sale, and serve as waggoneers for the local merchants.

[Page 294]