|

|

|

[Page 231]

by Khaim Cohen, Tzipora Kaminker, Avraham Toren & Israel Zeltzer

Translated by Moshe Kutten

Edited by Yocheved Klausner

I moved with my family to live in the colony of Sehaidak, when my father z”l was nominated as the Rabbi there. I encountered a Jewish settlement whose residents were farmers, people who work the land, there were no Christian residents and the administration was held by Jews. Instead of the [Russian] “Politzai” [police], there was the Jewish “Stutzki” who reported to the “Schultz” [elected head of the village], which was recognized as such by the authorities. All work ceased on Shabbat. I studied in “Kheder Metukan” [a modified Kheder in which general studies were incorporated along with traditional Torah studies]. During vacations, in the summer, I was lucky to receive, along with friends of the same age, a wagon harnessed to two horses, and transport bundles of crops or wheat from the field to the threshing machine in the farmer's yard. In the spring, I helped one of the farmers to tune the sowing machine (“Dril”) or to drive horses that pulled the plow (Buker). Sometimes I even received a horse for an outing pleasure ride, or a ride for a competition.

One of the colony's elders told me that in the year 5608 [1847/8], Jews came there from the province of Kiev, with the encouragement of the authorities and settled on the bank of a ravine which flows south to the River Bug, and the name of the valley was Sehaidak. They found a fertile and rich soil there that was growing a man-tall wild grass and began immediately with the construction of the clay houses. They kneaded the clay with chaff and made bricks in wooden molds which they dried in the sun. They quickly built small houses, plastered the houses from the inside and outside and covered the roof with straw. Over time, they built other, more modern houses from fired bricks and roofs made of tin or wood.

During the1870-80's, the government built the Kharkov-Nikolayev railroad. According to the plan, the railroad was supposed to pass near the colony; however, the farmers asked the government to build it farther away for fear that the noise would scare the poultry. The government accepted their request and placed the railway about 3-4 kilometers away from the colony. The members of the second generation regretted that decision, since the closest train station was placed 10-20 kilometers away, all the way to Dolinsk station, which became a train hub over time. Without a train station, the progress of the colony was slowed down.

Every settler was allocated land of 30 disiyatins [one disyatin = 2.7 acres] – about 300 dunams and some additional government land via leasing. With the growth in the number of descendants, the size of the family plots diminished, until a problem of land-poor farmers developed in the beginning of the 20th century.

The main crops were the grains in the winter, and corn, sunflower and watermelons in the summer. Another important sector was the cattle sector, which was based on natural pasturing in the summer and in the winter it was based on hay, which was harvested

[Page 232]

from fallow fields in the summer with the addition of bran. Due to the long distances to the city markets and lack of transportation, the milk was used to produce butter which was marketed to the nearby cities.

During First World War, refugees that arrived from Lithuania, who were experts in the production of Swiss and Dutch cheeses, developed a modern dairy plant where they produced hard cheeses and butter. As a result, the profits of the farmers who marketed the milk to the dairy plant grew.

A tall dam, which accumulated the rainwater, was constructed in the valley, producing a large reservoir, which served as an important source of water for the cattle in the summer as well as in the winter. Fish, named “koors”, proliferated in that lake. They would fish them out of the lake using a long net, tied with ropes that were pulled by people from the two opposite banks.

When the water froze in the winter time, the youth used to skate on the ice using iron skates. They used to cut blocks of ice from the lake even for the summer time. At the end of the winter, they used to announce a mandatory recruitment of all the men to cut the ice in the lake and to transport the blocks to a big storage cellar fitted for that purpose. Ice was provided to everybody, free of charge, and it lasted the whole summer for food preservation and for icepacks for the sick.

As mentioned above, the management of the colony was in the hand of the “Schultz” (the head of the colony), who was elected by the residents every several years (using confidential ballots). When the election day for “Schultz” approached, the number of people who criticized the incumbent increased, and the unrest against him intensified. Despite of that, the “Schultz” – the old Hershel-Aba Milman, of a shining face and clever eyes, was elected anew every time, and served as a “Schultz”, if I am not mistaken, until the day he died.

Like in every other Jewish community, a rabbi, a shu”v (slaughterer and Kosher inspector] and a healer (feldsher) served in the colony. Craftsmen, who made a living by working also for the farmers of the neighboring villages resided in the colony. They provided all the needed services to the farmers in the colony as well as the needs of the entire rural area.

In the colony they had a “kheder metukan” [a traditional kheder with the addition of general studies]where they taught both Hebrew and Russian as well as a regular “kheder” with a Melamed for Gemara studies.

My father, Rabbi Israel-Dov Cohen Z”l, always insisted on ensuring the existence of a high-level Kheder Metukan. He employed excellent teachers, graduates of the Yeshiva in Odessa and graduates of the seminar for Hebrew teachers in Grodno. The synagogue served not only for praying and studying of the Mishnah and “Ein Yaakov” [A book by Yaakov ben Khaviv and son, containing commentary and most legends from the Jerusalem and Babylonian Talmuds] , but also as the colony's house for the community committee and a hall for lectures and gatherings. It was always full of activities. Welfare organizations such as “Khevrat Talmud Torah” [literally – “The organization of Torah Study”], “Lekhem Evionim” [literally – “Bread for the Poor”], “Hakhnasat Kallah” [literally – “The Bridal Canopy”] and more were always present. Those who collected contributions for the welfare organizations were the school youths, who were going around the colony's homes once a week holding stickers' notebooks.

Until the February Revolution broke and the prohibition of the Zionism in Russia was introduced, the colony was mostly Zionist. Even after the Revolution, the Zionist Shekel [membership fee in a Zionist movement] was still being sold,

[Page 233]

and the activities of the JNF [Keren Kayement LeIsrael in Hebrew - the Jewish National Fund] took place. The JNF was very popular among the Jewish public and large sums of money were collected on holiday evenings, during marriage celebrations and Brith and Bar Mitzvah parties.

After the February Revolution, the Zionist party “Tzeirei Tzion” [literally-“Youths of Zion”] was active in the colony, and included many members. The party organized gatherings and celebrations that attracted the entire public. Branches of the [Zionist movements] “He'Khalutz” and “Maccabi” were also organized. An association by the name of “Geulat Akhim” [literally - Brothers' Salvation] which included about one hundred members was established. The members intended to make Aliya to Eretz Israel and work as farmers there, but their objective could not be realized because the Bolsheviks forbade the existence of the organization and the Aliya to Eretz Israel. Only some of the youths of the “He'Khalutz” and “Tzeirei Tzion” [movements] managed to illegally break through the border of Poland and from there to make Aliya to Eretz Israel. Part of them settled in Kfar Vitkin.

Following the October Revolution when the regime was transferred to the Bolsheviks, the number of gangs in the provincial cities whose commanders declared themselves as leaders proliferated. Their main sustenance was mainly achieved by robbing and looting Jewish colonies. An exceptional guard with weapons was organized in the colony. In 1918, a train full of people from the Hetman Grigoriev's gang stopped on the railroad near the colony, and the gang members started to march toward the colony and shoot at its houses. Panic descended, and the colony people escaped to the fields and hid amid corn and wheat stalks. Thanks to this mass escape, there were no victims, only property was stolen. However, that incident urged the colony youth to organize a proper self-defense force and every youth was recruited to weapon practices and guarding during the day and night. A common command center with the neighboring colony Ya'azor was established. The command center was responsible for organizing assistance and self-defense for the two colonies at times of need. Peace prevailed in the colony since then: the neighboring gentile villages spread the news about the establishment of a strong self-defense force. In 1919, when the Red Army retreated from the Dinkin corps [the Whites], which passed through the colony for three full days, a small cavalry company was seen returning from the same direction as the retreating army. The guard commander thought that they were a gang who came to loot the colony and ordered to stop the riders and shoot whoever approached the colony. However, these were a forward company of commander Budyonny of the Red Army. The vast army that followed the forward company surrounded the colony and conquered it through shooting by guns and machine guns. The guard commander and seven of his assistants were killed during that day trying to defend themselves against the soldiers. Twelve additional people were killed by the shooting of the soldiers. When the neighboring villagers heard about it they flocked to the colony in droves, robbed and looted everything they found in the houses while Budyonny soldiers stood by.

It is appropriate to mention and memorize the brave guard commander – Eliezer Zeltzer. His young wife – Shoshana, refused to be consoled and was the first in the colony who made Aliya to Eretz Israel as a pioneer. In Israel, she became a nurse in Kupat Kholim [an Israeli workers' HMO] and was devoted to her work with her soul and heart.

The colony of Yaazer was several fold more populated than Sehaidak, and was founded before Sehaidak with the help of the Russian government, who sent to it agricultural counselors of German origin. Several farms that stood at the edge of the colony and which were owned by German Christians,

[Page 234]

the descendants of these counselors, attested to that. What was the source of the Hebrew name “Ya'azor”? Rabbi Drabkin from Ya'azor gave me the answer. The colony was given a Russian name of a Pravoslavic church; however, the Jewish settlers wanted to change the name to a Hebrew one. They investigated and found out that according the Onkelus translation of the Bible, the name Komrin is a translation of the Hebrew word Ya'azor in the Torah book of “Bamidbar” (Numbers 32:3), so they converted the name to Ya'azor. Over time, the Russian government called the village by the name of “Izraelovka”; however, the Jews and the Christian neighbors called the village by the name “Ya'azor”.

Ya'azor's farmers grew, besides winter and summer field crops, also fruit trees and particularly grape vines. Since the colony was managed by a regional management (“Volost” in Russian), the management team of the credit union, common to the two colonies, was also located in Ya'azor.

When I recall the fields, the folklore, the lively youth, our Hebrew school and the people of the colony – my entire heart is roused. Was all of that really wiped out from the face of the earth?

We had one hundred families of diligent farmers, simple in their way of life but courageous in their spirit. Unlike other colonies, the farmers in our colony worked mainly in agriculture. In order to have wedding clothing tailored and shoes made, they had to travel to the city, as we did not have a tailor or a shoemaker in our colony. For many years we did not have a barber in the colony either, until one day, farmer Zeidel announced on himself as a barber. Zeidel was a very established and wealthy farmer who had hands of gold. He probably learned that profession by cutting the heads of his children. On holiday eves his house was full from end to end, some people were sitting and some standing, and the people who waited in-line argued about everything – about the Beilis Trial or an anti-Semitic article in the “Novoye Vremya” newspaper. It happened sometimes that one of the farmers, who knew how to play and sing, would begin to sing a Hasidic song, or a chapter from the praying book and everybody would join in. Even Zeidel would stop his work then and would conduct the singing crowd.

These simple and hearty Jews did not excel in general knowledge or in the Torah. They sent their children to study in the “kheders” by “melameds” [Jewish teachers] who were brought from the outside and were not all very knowledge in the Torah, the same way they studied during their own childhood, while more helping their fathers in the farm than studying.

However, during my youth, a fundamental turn in the area of education and study took place. This turn occurred

[Page 235]

thanks to two or three people, who instilled a new spirit into the colony. One of them was Rabbi Israel Cohen, who was accepted after his predecessor was fired due to his love for the bottle. Rabbi Cohen was a Lithuanian Jew, a great scholar, with nice attributes and Zionist views. He created an atmosphere of love of Torah and culture in the colony. His sons and daughters, who were educated by him, all made Aliya to Eretz Israel and became farmers. He himself made Aliya, several years later, and served as a Rabbi in Mount Carmel in Haifa, Israel.

The other person, who was a native of the colony, was Eliezer Popkin. From his early childhood, he excelled in the study of the Talmud. When he was Bar Mitzva he studied in the Yeshiva of Kremenchug, and stood out with his talents and persistence. From there he transferred to Lubavitz, the center of the Khabad Hasidism, to study the “Revealed” [traditional Jewish Halakha interpretation] and the “Concealed” [Kabalistic Jewish Hasidic interpretation of the Jewish scriptures]. During his Torah and Talmud studies, he was exposed to general books. He left Hasidism and began to study in the Yeshiva in Odessa where Kh. N. Bialik [greatest Jewish and Israeli's Yiddish and Hebrew poet], Dr. Y. Klausner [famed Jewish historian and professor of Hebrew literature] and the “Rav Tzair” [“Young Rabbi” - the literary name of famed author, teacher and Rabbi - Khaim Chernovitz] were teachers. Popkin was the one who founded a modern Hebrew school, whose students spoke modern Hebrew, read Hebrew books and wished to make Aliya to Eretz Israel.

A partner to the educational activity of Popkin was Shmuel Dashkovitz. He was among the graduates of the Yeshiva of Odessa who married one of the colony natives. He settled in the colony and served as a teacher in the Hebrew school. When Popkin was nominated as the principal of the Hebrew school in Samara and joined the agricultural university, Dashkovitz continued his educational activity. Many of the youths of our colony made Aliya to Eretz Israel and became diligent farmers in the workers' moshavim.

During those days, revolutionaries who acted underground were suspected by the police and those who were about to be arrested escaped to far corners. Our colony served as a convenient hideout for Jewish suspects from the near-by cities, since the police considered the colonies as consisting of simple farmers “clean” of the revolutionary virus. These refugees, most of them educated people, were bored in the colony from being idle. Therefore, they found an interest in connecting with the local youths and spreading, among them, the revolutionary ideas. Among them, there were Zionists who preached Zionism and Socialism. Due to their resistance to the Czarist rule, many of them refused to enlist into the army during the war. For these people, and for those who enlisted and deserted, our colony served as a safe shelter. We called them “hares”. Under their influence, there were local youths who refused to enlist. The “hares” could not be seen in the streets during the days, due to fear that a farmer from the neighboring villages, who knew all the locals, would see the strangers and notify the police. A special committee ensured that the “hares” would not be seen outside, particularly during the days of the “fair”. Upon Kerensky's-Revolution, the colony was emptied entirely from these guests.

The awakening of the Jews following the revolution in Russia did not pass over Sehaidak. The percentage of Hebrew knowing people in our colony was the highest among the Jewish farmers in Southern Russia.

[Page 236]

The youth used to organize Purim and Hanukkah celebrations, present shows and call for gatherings to discuss the state of the Jews in Russia but mainly about Zionism and making Aliya to Eretz Israel. In our Zionist activity, we were helped by Zionist leaders such as Zeev Tiomkin, Dr. Stein and especially one of the leaders of “Tzeirei Tzion” – Nakhum Verlinsky. He was a brilliant speaker and very active among the youth circles. Like in other Kherson colonies, youths from the nearby cities came to Sehaidak to receive agricultural training before they made Aliya to Eretz Israel.

When the Bolsheviks took control and the borders closed, our Zionist activity became more difficult from one day to the other. The roads for making Aliya were blocked. Some of the colony natives joined the Komsomol, which hindered our activities and there was also the fear of imprisonment. In order to escape the control of the authorities, we organized in small groups and secretly left the colony. We made our way at night. We moved to the city of Berdichev, where we lived as a commune for a year and a half. From there we went through Poland and Romania, experienced adventures, and faced life dangers. Under difficult conditions including under-nourishment and exposure to infectious diseases, we finally arrived in Eretz Israel.

Thanks to our agricultural past and the life of work, which we grew up on and our Zionist-Hebrew background, most of us continue here in agriculture and other work-related occupations. About forty years passed since we left. Children and grandchildren were born to us. As a state we were granted independence; however when the memories about the colonies are brought up, our heart is wrenching. The colony with its hearty, good and simple farmers who excelled in working the land and in working with their hands; this unique and wondrous Jewish folklore – where is it? Except those who made Aliya to Eretz Israel and the few who escaped to other countries, everybody else was murdered by the preying animals, and the land of Sehaidak, which was plowed and cultivated by Jews for more than a hundred years, was cleared entirely from the Jewish effort and work, from any Jewish foothold.

May these lines serve as a memorial for the pure and innocent victims!

Since the beginning of the century, the farmers in our colony established themselves substantially, thanks to the help of counselors, the cultivation using modern tools, the good organization of the local institutions, and most of all thanks to the youths and the local children who got used to the work and learned to love it. Unlike other colonies, the fields of Sehaidak were close to the colony. That eased their cultivation. Beside the field crops, many expanded the cattle growing sector. Some of the farmers established themselves to the point of being wealthy. Those farmers, whose farms are not as developed, worked in transporting the grain to the city.

[Page 237]

This became a secondary sector of agriculture, even by most of the Christian farmers in the neighboring villages.

Our teacher, Popkin, established a school where they taught “Hebrew in Hebrew”. Under his initiative, a Zionist club of young farmers and youths was established. During the war, Popkin instructed a youth club belonging to the politically right section of “Tzeirei Tzion” [“Youths of Zion”] movement. We established a public library, which contained many books in Hebrew, Yiddish and Russian. Thanks to our Hebrew and Zionist education, our colony contributed a substantial number of pioneers, most continue in Israel as farmers. Unlike in our colony, only a third as many made Aliya to Eretz Israel from our big neighboring colony Izraelovka (Ya'azor).

During the war, our colony experienced all of the calamities experienced by the other colonies – enlistment of the youths to the army, recruitment of the horses for transportation and confiscation of food products. Our colony also experienced a shocking murderous event. Gangs who murdered hundreds of thousands of Jews throughout Ukraine and destroyed entire communities, did not dare to break into our colony, due to the self-defense force, organized and armed by the colony native Zeltzer z”l, a young brave man who served in the artillery corps during the war.

Fate would have it, that the mass murder was rather executed by a company of the Red Army. The event happened due to a critical misunderstanding. When the army company passed near the colony it unarmed two of the defenders. To Zeltzer, this company was suspected of being one of the murderous gangs, and he ordered to shoot at it in order to prevent it from entering the colony. These shootings raised the anger of the company's commander. Despite the fact that nobody was hurt by the shooting, he ordered to break into the colony and take revenge. During the next few hours, they managed to murder close to forty people, among them, the self-defense force commander. They also did not shun from robbing and destroying the colony during their stay.

If before, it was only the wish of the Zionists and “Tzeirei Tzion” to make Aliya to Eretz Israel, then after the bloody event and the taking over by the Bolsheviks, everybody wished to make Aliya. One initiative man by the name of Dr. Stein from Yelisovetgrad, organized the colony's farmers and some additional members from the city into a cooperative, which aimed at making Aliya and settlement in Eretz Israel. A committee was selected, by-laws were established, and a plan to send a delegation to Eretz Israel, in order to guarantee an area for the settlement was formed. However, in the meantime, the borders were closed and it became impossible to implement a mass exodus. The bachelors and the bachelorettes took some provisions for the road and some belongings and set out towards the borders. All of those who managed to steal the borders arrived in Eretz Israel and settled in it. The others, particularly those with families, waited for an opportunity and missed the opportunity. During the late 1920's the colony was announced as a kolkhoz. During the Holocaust, the cruel end came to the colony and its Jewish residents.

[Page 238]

The name of my native colony was different from the names of other colonies in the province of Kherson, which all had Hebrew names such as “Sdeh Menukha” and “Ya'azor”. Our colony was named after a Ukrainian national hero – Sehaidak. Sehaidak and Ya'azor, which was located six kilometers away, were established farther away from the rest of the colonies of the Kherson province, and farther away from the provincial cities and the rivers flowing into the black sea, as if they were simply thrown into the fertile prairie.

There were two elongated streets and one hundred households in the colony. The houses were covered with straw or wooden roof tiles, and did not differ from the other farmers' houses in the area, except some large houses, and small business houses and groceries, which were crowded with shoppers during the market days, when the gentiles from the area came to sell vegetables and fruit and buy kerosene, fabric etc.. During the market days, we caused worries to the “melameds” [Torah teachers], who taught us Torah and fear of G-d. Instead of studying the Torah portion of the week, a Mishnah chapter, or the Baba Metziah Tractate, we ran around the market stalls and came late to the lesson bringing back with us all sorts of “bargains” – blueberries, plums or sunflower seeds. We hid these “bargains” well inside our pockets for the fear of our “Melamed” who would harshly punish those which were caught. The temptation was strong, despite of the potential punishment, perhaps because they did not grow fruit trees and vegetables in our colony. There was only one settler in our village, who owned a big orchard with all sorts of fruit. He also owned a beehive. He was a watchmaker and his name was Alter “der Ligner” [“The Liar”]. Why would they stick a title like that to him? Probably because he had no difficulties in bragging about his fruit harvest, and tell exaggerations about his inventions with new fruit strains. We – the youths, “helped to reduce” the size of his harvest. We knew about all sorts of breaches and openings through which we entered the orchard in order to taste from his first fruits, and also put some in our bags.

The main sectors in our colony were cultivation of field crops, cattle and production of Dutch cheese. The yards were large and fences made of cattle manure. The soil was fertile and it was not profitable to fertilize the fields. The manure piles would break apart and fall into the lake that was stretched along the colony and would feed the fat tilapia fishes. Every holiday eve, the gabbai [synagogue administrator] would bring fishermen to the lake who spread the net from one edge of the lake to the other. The entire village

[Page 239]

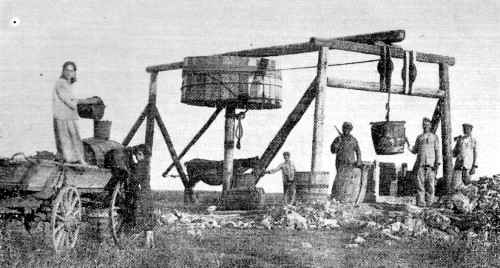

would go out to pull the net's ropes. The fishery was abundant, and the sale revenues paid for the expenses of the synagogue, the public bath and the rest of the public needs and it was even possible to hire a cantor for the “Days of Awe”. The peak in the agricultural work was the threshing, which ended by putting the grain in the barn. Young and old worked in the threshing. Ladder wagons loaded with sheaf would unload the crops into machines. The uproar of the threshing machines, the dust clouds and the flying straw were common scenes in all of the yards.

We the children, were educated initially by a “melamed” and later on by the village's native, Eliezer Popkin, who graduated from a teachers' school in Zhitomir. He taught us Hebrew poetry and literature. He was also the person who established a club of the Zionist movement “Tzeirei Tzion” which was actually a branch common to two colonies.

I lived peacefully until the age of seventeen. I was seventeen years old when the revolution broke. “Freedom harbingers” ran around on the roads and fields chasing after the “bandas” [gangs] of Petliura and Makhno [Ukrainian leaders that fought for Ukraine's independence during and after the revolution]. Several retreats and assaults by the various camps passed through the village. We were horrified by the frequent mad trampling of foreign people and vehicles. The “bandas” did not hurt people, only imposed taxes and demanded supply of food for their soldiers. Our self-defense was aimed not toward them but toward the gentile villagers who boasted that they would attack the Jews for the purpose of rioting and robbing them.

My uncle, Eliezer Zeltzer organized the self-defense force. He was a sergeant in Czar Nikolai's army. He organized about 40 youths, natives of the colony, and acquired weapons and ammunition. He placed guards at the entrance to the village, and every convoy that passed through the village on the way to Dolinsk (the train station) was checked thoroughly and its weapons confiscated. Indeed, there were no attempts to attack the colony. We would have probably been able to pass through the regime change unscathed, except for the case when battalions of the Red Army passed through the colony. One of the battalions, which returned for some reason to the colony, was mistakenly thought to be one of the gangs which wanted to loot, rob and murder. My uncle ordered to resist forcibly and not to let them enter the colony. The rest of the battalions, which also returned following that battalion, encircled the colony and started to shower it with fierce firepower. As a result, most of the defenders were killed, among them my uncle Eliezer, the commander of the self-defense force, as well as some elderly people who were killed by stray bullets. Since then, we had the feeling that we are not residing on our own land. The colony was vulnerable to rioters and robbers, since we did not have the means to resist them. Most of the residents left the colony and traveled to the cities and to relatives in other places. About 10 youths arrived in Eretz Israel and most settled in Kfar Vitkin.

[Page 240]

From letters we received from relatives, we found out that the remnants that stayed in the colony experienced years of hunger. Most died in 1921 and the rest scattered throughout all corners of big Russia which was so cruel toward people who worked the land, whom the state professed to help.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Jewish Farmers in Russian Fields

Jewish Farmers in Russian Fields

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 4 Nov 2018 by LA