|

|

|

[Columns 679-680]

by A. A. Zommer / San Jose, Costa Rica

Translated from Yiddish by Miriam Bulwar David-Hay

Like all Jewish towns in Poland, Hrubieszow was full of Torah and prayer. If a Hrubieszow resident crossed over the Bóżnica[1] Street, he would have seen with his own eyes everything that had happened with the Jews since the situation at Mount Sinai.

On Bóżnica Street, in first place stood the town synagogue, which was built in the year 5632 – 1872. In large letters shone down from it the passage:

“Lekach tov natati lachem, torati al taazovu.”[2]

Opposite the town synagogue stood the rabbi's beis midrash[3]. On Shabbat afternoons Bentche would teach Torah there before a fully packed hall. When he had finished, one did not want to leave, one wanted to hear him more and more.

More than once it seemed to me that sitting there was Moses Our Teacher himself in all his dignity and with us was studying Jewish law that he had not managed to write into the Chumash[4] … and actually Bentchy was not a rabbi and was not a dayan[5], but a simple ordinary Jew.

East and west of the large beis midrash stretched an entire chain of Hasidic shtiebelech[6] – the “provinces” of the kingdoms[7] of Belz, Kotsk, and Ger[8], Kuzmir[9] and Zwolen, Warka and Amshinov[10], Trisk[11], Kozienice and Lubavitch[12], Sanz[13] and Bobov[14], Sochaczew and Kosow[15], Chortkov[16] and Boyan[17], Dzikow, Rozwadow and Żarna, and still others.

Not far from there was the site of the “Poalei Agudat Israel[18].” I was led into it by my dear friend, Reuven Fabrykant z”l[19]. There was the kingdom of Rabbi Shimshon Rafael Hirsch[20] z”l, with his famous “Nineteen Letters on Judaism.”

A bit further on was a site full of the young, who were followers of Dr. Itzchak Nachman Shteinberg[21] with his “free writing[22].” Still further on was a club where there were hanging pictures of Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, Rosa Luxemberg, and Gustav Landauer[23], all three [men] with respectable beards, although one was a gentile, the second an apostate, and the third, Landauer, a Jew but far from Jewishness …

Nearby were the sites of the “Bund[24],” [and] of the Zionists, “Mizrachi[25]” and revisionists[26].

When one crossed over the Zamosc bridge, one stood on the site of the Poalei Zion Right[27], with its pictures of Moshe Hess, Nachman Syrkin, and Ber Borochov[28]. There Eliyahu Gertel was active. I was led in there by my unforgettable friend Mendel Moskol (today in Israel).

These assorted parties sharply fought, polemicized, scolded [each other], but in truth they were instruments in one orchestra, which played the symphony – Jewish life.

And this was how things were until the 1st of September, 1939. Until from all of that, not a single trace remains.

B. [Part II]

On the 2nd of December, 1939, the German military commander, General Ebner, ordered that all Hrubieszow men from 16 to 60 years of age should assemble at the church square. We had already heard that in this way in Kalush[29] all the Jews had been shot. Most of the Hrubieszow Jews hid themselves, but about 2,000 Jews nevertheless presented themselves. They began to hurry the assembled along and drive them over the fields. Those who did not manage to run so fast were shot. Eight hundred and thirty victims fell then.

After the events, my father Chaim Nachum z”l took his wife Tzipora and his four small children, Temeleh, Rucheleh, Chanaleh, and Aideleh, and with them was away to the village of Masłomęcz, which is 15 kilometers from Hrubieszow[30], and hid himself in a potato cellar at a peasant's house. One evening the peasant drove out of Masłomęcz with his cart, with his wife and children. He drove on the road towards Hrubieszow and was made up and disguised in my father's cloak and hat, and he wore a stuck-on beard and sidelocks. This would tell those around that Chaim the Masłomęcz man with his household members had that night left the village.

After driving a piece of the way, he put on his own clothes and along a different road drove back home.

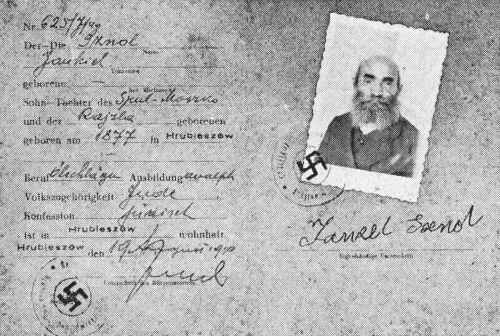

Until the middle of 1941, my father succeeded in hiding out in that damp, dark potato cellar. That was his home and his house of prayer. After praying and studying [the Torah], he sat in the cellar with a small light and wrote in a notebook. I do not know what he wrote, but I imagine that he wrote interpretations from the Torah, memories, and probably a will for his children, who might possibly outlive the German murderers.

There, in the dark bunker, it is likely that many things became clear to him that he could not understand in normal conditions. There, in that dark cellar, his pitch-black beard became snow-white. Perhaps that white beard also helped light up that dark cellar.

The household members sat there and repaired old clothes, in some of which they had to wrap themselves. And perhaps, one of my sisters let them hear a quiet melody there in the cellar, to hold them up and comfort them.

It is likely that a peasant became aware of the hiding place and he decided to earn a few kilograms of sugar, or just thought it a good deed to kill a Jew, and he turned them in. The Gestapo caught them, led them out to Hrubieszow, and imprisoned them in the ghetto.

In one of the aktzias[31], perished my father Chaim Nachum z”l, his wife (my stepmother) Tzipora, and my four little sisters: Temeleh, Rucheleh, Chanaleh, and Aideleh, who had not yet reached three full years of age.

May God avenge their blood!

|

|

Translator's Footnotes:

by Naftali Myal[1] / New York

|

|

We were four brothers and one sister, all married. The eldest brother, Yaakov, with his wife, Ester; the second brother, Kalman, with his wife, Rachel; the third brother, Shimon, with his wife, Elka. The sister, Czerna [Tcherna], married in Warsaw to Feivel Sheinberg, and perished in the Warsaw Ghetto.

Our parents, Kalman, Shimon's wife with their two children, Kalman's little girl, and I lay hidden in a bunker. After that I ran away from the bunker and hid out, and thanks to that I saved myself. All those who remained in the bunker were discovered and they shot them on the spot. That happened on the 15th day in the month of Cheshvan[2], in the year 1942.

I wandered around then for several weeks. At night I managed to get myself bread and water. But it was impossible to ramble around like this further and not fail. I became aware then that on Jatkower Street there were still a few Jews to be found, who had been released from the capture because they were tradesmen. They advised me to hide myself further and not to be with them. When there would be a chance and they would need me, they would let me know.

The cold did not allow me to lie in the fields at night for long. I went to them again and they promised to take me in to the workshop where they worked for the Germans. The Germans needed tradesmen, and already then there were not many of those. I began working there, and this went on for a year, until the summer of 1943.

During that time, the Germans once took out 25 men and women, led them to the cemetery, and shot them there. Among them was also my wife, Miriam. My child of two and a half years lay hidden with another child in a house, the Germans discovered them, and in front of my eyes shot them. Afterwards I dug a grave and buried both children. I was scared to carry them to the cemetery and give them a burial there.

There were among us several who were hiding weapons. Jewish informers carried this [information] to the Gestapo. Once the Gestapo chief came and told us that he knows that we have weapons and are preparing an uprising. Oddly, he says, he should shoot us immediately, but this time he will satisfy himself with sending us for hard labor in another site.

A few days later, the S.S. surrounded us and they drove us away in closed wagons. Those who tried to run away were shot on the spot. They drove us to Budzyn[3], to the camp there.

Several days later, when the locals saw that we still looked not at all bad in comparison with them, they began, out of jealousy, to say loudly that we had come there to stir up a revolt, and that this would bring misfortune on the whole camp.

They brought the talk, it seems, to the camp commandant. He gathered up all the Hrubieszow people and gave us harsh exercises as a penalty. We had to crawl on our knees and elbows, quickly, quickly in the mud, and the Germans emphasized that we should hurry up with whips.

Straight after the exercises we had to go to our work in the forest. There we built barracks and around them stretched electric wires. With this we were preparing a new camp for us.

One night the S.S. unit came with the rumor that the Hrubieszow people want to run away, and they shot many of us.

We then began working in the workshops of the Messerschmidt[4] airplanes. This lasted for half a year. After that they sent us to the concentration camp in Mielec[5]. There we had a Jewish camp head who wanted to curry favor with the Germans, and he treated us cruelly. In Mielec too we worked in the Messerschmidt workshops.

After several months, they sent us over to Wieliczka[6]. There they already separated the men from the women. Two weeks later they sent us to a concentration camp in Flossenburg[7]. There they took away all our clothing and we went around naked, as God created us. Three days we went around like this, until they engraved numbers on our foreheads and our backs[8]. On the fourth day, they gave us concentration camp things, a pair of pants and a jacket with stripes, and they sent us over to Leipmeritz in Czechoslovakia[9].

There we met Poles. They wondered strongly that there were still living Jews in the world. They planned out a false accusation against us, that we had said that we would not drink any coffee without sugar. S.S. men with guns wanted to shoot all of us on the spot for this. But a German Jew convinced the S.S. unit that the Poles had simply planned a lie against us. Then they divided us off from the Poles, [and] we only worked together, but eating and sleeping – separately.

In the camp we worked at various jobs for around 10 months. From there they sent us to the tragically infamous concentration camp in Austria, Mauthausen. We were there for two days and they sent us away again to a different camp[10], where they immediately told us that no one could hold out there longer than six weeks, because they beat and they tortured [prisoners] extraordinarily.

Had the war kept going for four more weeks, none of us would have been alive already. But God helped, the miracle happened, and within two weeks, the war ended.

The S.S. unit suddenly ran off. We were left without Germans and we did not know what to do, we were all worn out and sick, we lay and waited. Two days later, in came the Americans. That was the 8th of May in the year 1945!

As soon as we had rested and eaten a little, and our strength had returned to us bit by bit, we set out to travel to Poland, to search out the remnants of our near ones. But I already met no one of my family. Even my brother, Yaakov, who had gone over to Russia, perished somewhere from hunger.

We were in Lodz[11] for a short time, searched, inquired after [relatives and acquaintances], and afterwards I traveled to Hrubieszow, to see what had become of our town. I saw the destruction there and I left the town as quickly as possible. I traveled over to Germany, in the American zone, and from there to New York.

Translator's Footnotes:

by Natan Gvirtz[1] / Maanit, Israel

Translated from Hebrew by Miriam Bulwar David-Hay

Twenty years have passed since the greatest disaster in the chronicles of our people happened, since the black and terrible demon burst on to the towns of Poland, laid waste to, and destroyed the glorious Judaism of that country without consideration for the father, the mother, and the newborn.

Today, after such a long period, when you try to remember and to reconstruct in your imagination all those events and horrors that passed upon us, it still cannot be believed that your hand is capable of placing all this on paper. But given that we all swore that “everything will be remembered and nothing will be forgotten,” we will together eternalize in this book everything that passed upon us, and it will be used as documentation for those who did not remain alive and “whose song was stopped in the middle[2].”

The things that I am placing on this paper are not only a story. They are the horrors of the Second World War in the city of Hrubieszow.

In the year 1940-1941 - and I was 10 then - the great persecutions began against the Jews of Hrubieszow.

At 27 Rynek Street, in a narrow lane next to the market, stood our old house. On the front, above the door, was a small sign of tin and on it were engraved the words “Moshe Gvirtz” (in Polish), in the name of my grandfather z”l[3].

In that house, on the top floor, my father announced: Children! Given that the pogroms are continuing and increasing, and there is no knowing what will be tomorrow, I am forced to give up on my fatherhood of the family, and I suggest to each one of you to do everything in order to flee from this hell and to try to save your souls.

In trembling and in sorrow, my father handed out small bags with a few items to each child, and left. He went to a place where thousands of Jews went and from there never came back.

In the shelter

Indeed, after that family meeting, only a few days passed and we began to disperse. The older ones among us tried to find a refuge on the Aryan side of Poland and to get by as Poles, the little ones stayed next to our mother.

In our house there was a small shelter, which had already been prepared at the beginning of the events, and there we accumulated food, water, and salt, for every trouble that might come. Leading to the shelter was a small opening, which could only be entered in a crawl, and a wooden bed hid it. There we lay, I, my mother, my younger brother, and my brother David, who remained alive for long days.

The hand of an author cannot describe the shelter and its conditions: the dirt and the lice that infested it. But the main problem was: food, the quantities of which grew less, and hunger began to trouble us.

Each and every day, twice or three times, the German announcements were heard from the narrow street:

– Jews, present yourselves!!! Jews, come out of your hiding places and nothing bad will happen to you, we will take you to work!

But everyone knew the meaning of their words. After that the searches began, which were carried out by the Poles and the Germans in every house, room, and hole. The Poles were given a salary for their labors. They robbed and looted the property from the houses and the Germans discovered additional hiding places and shot the Jews on the spot.

I remember well the search that was done in our house. Over half a day they took everything apart in the rooms, the wardrobes of clothing, the dishes, the blankets, and the beds. As we lay in the shelter, we felt the footsteps of the Germans in the room.

Suddenly they began to move the bed, which hid the entrance to the shelter. Our hearts did not beat, only our eyes hinted to one another: This is the end! Soon we too will be taken out of here!

And suddenly a turning point, quiet, they went and we remained.

We scampered away from the shelter

The Germans decided to establish a ghetto in the city. My brother David also presented himself, and, fortunately, was accepted for work in the ghetto.

From then we remained three in the hiding spot, I, my little brother, and my mother z”l. Every evening one of us would go out of the hiding place to bring us food, which we received from my brother in the ghetto, and sometime we would also buy [food].

One evening my little brother went out to bring food. He was caught by the Germans and was killed. Those were days of mental torture for my mother, and mainly because that the matter became known to her after many days of waiting for Areleh to come back. But he never returned.

May his memory be for a blessing!

Thus we remained, I and my mother alone. We lay there for many days until we decided to change the hiding place and we set it in a storeroom for firewood, under the stairs that led up to the house.

For many months we lay in that small storeroom, and my brother David would bring us food. In that hiding place my mother grew weaker and thinner from day to day. She could not get up, because there was no room to straighten out, and her condition worsened.

It is very hard to remember what we spoke about over the course of days and months, but my mother's main occupation was guarding my cleanliness and destroying thousands of lice from my head and from my clothes.

One day a Polish family decided to come in to live in our house and on the same day the “gentile” discovered us and said:

– It is my desire to inform you that I am coming in to live in this house and until tomorrow morning I am giving you the opportunity to get out of here, and if not, no option will remain in my hands except to give you up to the hands of the Germans.

My mother fainted. I begged the gentile not to expel us. This is our house, my mother is sick and cannot walk, but the gentile did not add more and left.

It is clear that no choice remained except to scamper away from that hiding place. In the middle of the night, I took my mother, and with the remnants of her strength, leaning on my back, we went in the direction of the ghetto.

The fateful night

It was a cold night, the skies were clear and checkered with thousands of stars.

Are there still, in truth, as many Jews as the number of stars in the sky[4]?!

When we arrived in the ghetto, we found a place and hid there. Here in the ghetto, our situation improved a little, because it was close to my brother David, who took care of us. In this hiding place we continued to lie, and no one knew about this except my brother.

Otto Wagner, the mass murderer of the Jews of Hrubieszow, would go around in the ghetto days and nights and follow everything that happened inside and outside it.

I cannot remember exactly how much time we lay in that hiding place in the ghetto. On one of the nights, at midnight, my mother and I were sleeping the sleep of the just, when we felt a powerful flash of light, which covered our faces. It was a powerful light and we did not know from where it was coming. Behind the light nothing could be seen. After several minutes of being blinded, I heard a voice in German:

– Who are you? What are your names? When did you come here?

Neither I nor my mother answered anything. The German repeated the questions, accompanied by curse words. Again in this case my mother did not let out a sound from her mouth and lay as if turned to stone. I was frightened and was trembling all over. In the end, slowly, slowly, my confidence returned to me and I said in Polish:

– [I] don't understand!

Wagner the German, the mass murderer, pushed the door forcefully and went out.

We remained. In that same moment I heard a large and heavy groan from my mother's mouth. I touched her limbs and they were cold. I stroked her face, threw myself on her, and shouted:

– Mother!!! Mother!!! Recover, he has gone, we have stayed alive, he will not come back again.

But my mother did not reply, only moaned.

In that moment the German appeared again with a young woman, I do not remember who she was, and he told her to be the translator. The German began to ask the same questions again in German and the girl translated them to Polish. To his questions I replied:

– We arrived here only this evening from the area of Zamosc[5], and we do not know anyone here. I and my mother are sick and we could not continue, therefore we decided to rest here.

I begged

[Columns 685-686]

him to accept us for work, we can do everything, both I and also my mother. After that he said:

– Tomorrow morning you must present yourselves to the head of the ghetto.

Given that we could not run away, because it was not within our physical abilities, the next day in the morning we went to the head of the ghetto and we were accepted officially.

In the labor camps

From that time on we lived in the ghetto together, until one day it was decided to liquidate it and transfer all the Jews to the city's prison. From there all the Jews were transferred in cars to freight carriages at the train station and from there to the labor camp Budzyn[6].

The Budzyn camp was the first where we felt coercion and hunger. Here our civilian clothes were taken from us and we were dressed in the clothing of prisoners, with stripes. Each person was just a number to them. The camp was fenced with electrified wire and around it were guard towers of the Ukrainians.

Each and every day, in the early hours of the morning, we were assembled for the “Appell[7]” and after that we went out to work.

We would return late and tired, worn out and hungry. After that long lines would form next to the kitchens and there we received the daily portion: a spoon of soup, 150 grams of bread, a piece of margarine, and a spoon of jam. That was our daily ration, we divided it up so that it would last for the whole day. It is clear that this deficient nutrition caused exhaustion and illnesses.

How I was saved

Every month, always on a Friday, a special inspection was carried out and all those who were sick and unfit for work were loaded on to the [train] carriages to the gas houses[8]. The special problem that I faced: how to appear big, so that I would not be disqualified at one of the roll calls. Given that the inspection was always conducted in the same place, I brought with me a large stone, which I placed under my feet, and it rewarded my faith and made me large and worthy of tortures.

Much has been given to me to speak about this camp. Every day and every night and its events. There was not a day without an execution for the transgression of theft, an attempt to escape, or weakness.

The hardest days were Fridays. I remember one Friday. I and two friends of my age decided not to go out to work. We were tired from the hard labor during the week and we stayed in bed.

Precisely on that Friday a census was conducted in the camp. The Germans went from hut to hut, from bed to bed, and dragged everyone outside. Of course, they also found us and stood us there for this census.

This time the commander of the camp himself appeared, accompanied by the doctor, so as to receive an explanation on the conditions of those who were ill. I knew that this commander was the last one for me.

As we were standing in rows, the camp commander passed by and pointed at each person who in his eyes looked exhausted or sick, and the doctor, who was behind him, tried to explain his condition. I do not remember exactly how the thing happened, that despite everything, I remained in the camp and I was not sent away with the “Musel kommando[9],” as they would call those who were sent away [to their deaths]. I only remember that he pointed at me and said: Raus[10] (outside), and he continued walking.

I, it seems, did not obey him, and that is what saved me.

After Budzyn we passed through an entire line of concentration camps, and each camp with its own specific problems.

The Wieliczka[11] camp was the last camp where I still saw my mother. It was then that they took her and I did not know her fate. That day that we were separated was the hardest in my life. I asked for death rather than remain without a mother, because it was only thanks to her that I had the strong desire to remain alive. I also knew that she needed me. Despite the harsh torments that passed upon us, she was a proud mother, who instilled in me confidence and faith that the day would come and we would be freed.

Despite the sorrow and the pain, we continued to live. We went through many camps, until we arrived at Zschachwitz[12] next to Dresden. In that camp was a factory for tanks, and above the factory, on the fourth floor, they set our living quarters.

Here we lived for a relatively long period. In this camp there were not many prisoners, and special to it was that the prisoners were from many countries. There were Germans (German criminals), French, Russians, Swedes, Ukrainians, Hungarians, and more. The regime was harsh and the conditions of the prisoners were difficult, mainly from the point of view of food. Food was given here sparsely and was of poor quality, people suffered from bloating[13] and from other side effects.

On one of the nights, a group of Russian prisoners carried out an escape from the camp with the help of long ropes that they tied to the window sill. The next day they were caught and killed. As a punishment a new commander was sent over us, who treated us severely and caused us many tortures.

On one of the hard days of winter I got up from my bed in the morning and I felt strong pains in my throat. In the camp there were two Hungarian brothers who were doctors. I was very well liked by them. I came to the older brother and I told him about the feeling in my throat and that I could not swallow. Of course, the doctor checked me and ordered me to stay in bed for a number of days. From experience I had learned that to be sick in a camp was a dangerous thing. Therefore, I did not agree to lie down and I continued working.

My situation is did not improve, but grew worse. At nights I did not sleep and I did not have air to breathe. I felt as if something was blocking the air in my throat.

I went to the doctor again and he decided: diphtheria. I was placed in the sick room, where about 20 people with assorted illnesses were lying. Some of them had been infected with typhus, [or] dysentery, and some suffered from bloating.

The two doctor brothers ran around days and nights in the sick room and gave help, but what could they do without medicines. Every day, they covered another person with a blanket [because the person had died].

Indeed, my condition grew worse too, and I again saw the angel of death hovering above me. The doctor tried to cure me in a variety of ways, heated up water and gave me to breathe the steam, but he knew that if he did not obtain injections he would not be able to save me. He went to the German who was responsible for the sick Germans and firmly demanded the injections. He received them too, injected me with them, and after a number of days I spat out a lump of pus, and I recovered. I thanked the old and kind doctor.

There was not a person in the camp who did not like the doctor brothers. I remember that they promised to visit me after the end of the war. But a great disaster happened to both the brothers. First the younger one fell ill with typhus, and his brother tried to save him with an injection of his own blood, but to no avail. After about a month the second brother died too, and thus were taken from us two brothers, doctors who were good and beloved by the whole camp.

Their deaths left behind heavy mourning.

The great bombing

As we came closer to the year 1945, the atmosphere became more tense. Those responsible for the shifts at the factory began, slowly, slowly, to reveal that the end of the fascist regime was drawing near. Day by day, night by night, the [air raid] alarms at the factory were constant and the people were sent down to the [bomb] shelters. The heavier a bombing was, the more it infused us with the belief and the hope that in the end the Germans would be destroyed.

On one of the nights, the fateful bombing of Dresden was carried out: All that night, until the morning, the city was bombed and the surroundings turned into pillars of smoke. Only the factory in which we worked remained whole.

The Germans still did not believe in their failure. The gathered us up and led us on foot in the direction of Terezin (Thereisenstadt)[14].

Those were hard days. During the times of bombings, we waved at the airplanes in our prisoner clothing, so that they would not bomb us.

When we arrived at Terezin, we were exhausted, and at the gates of the camp we were received by Czech Jews, who gave us food and water.

In Terezin, diseases were rampant and dozens of people died every day. We knew that the Germans were planning to operate the gas houses but they did not succeed. After about four months of staying in the camp, the Russians arrived. That was on the 8th of May, 1945.

One day before the end of the Second World War[15], I was liberated from the hands of the German murderers.

Dear readers! I have brought before you a short description of the horrors and the torments that befell me during the five years of my stays in camps and ghettos.

Translator's Footnotes:

by Manya Lerech, Bat Yam, Israel

Translated by Miriam Bulwar-David Hay

|

|

It was in that time, when they were sending hundreds [of Jews] out for forced labor, that they [the laborers] no longer came back.

My father and brother found themselves in a small village next to Hrubieszow, and they hoped that they would succeed in holding on to life, them and the family.

My father knew the area well, he had many acquaintances here, but he had changed greatly. His peasant acquaintances put on an act as if they were seeing him for the first time, slammed their doors in front of him, and told him to go away again.

My father found one friend in the village, an old, hunchbacked peasant. He was once a groom in the Morgenitz yard, he often used to come into our home, and in that moment he did not shake my father off. He found an old, broken shed and squeezed my father and brother in there. In a second village he found a similar place for my mother and sister.

Night after night the old man came to the shed, pulled out from under his clothing a few cooked potatoes, a black bread, and often even a small piece of meat. He left behind a few warm, heartfelt words, then he quietly went away again. He took even more care of my sick mother and sister. He did all this in secret. He guarded himself even against his own wife and children.

Once, on a fine spring night, my father and brother came out of their hiding place, restless, more than always. For several nights already their friend had not come to them. What could have happened? The last time he was there he had been greatly preoccupied. He told them that for the past two days already the Gestapo men had been getting drunk in the Pritzish yard. They were having wild orgies there, and who knew with what this would end. He also warned my father and brother not to dare to go out of the hiding place. But several days had already passed, they could not wait any longer, they had to still the terrible hunger, and they had to know what was happening with the sick wife and daughter. Today already they must drag themselves there.

Normally it was a 10-minute journey, but for those who had to steal through among the trees, crawling on their knees, this was not an easy thing.

Bloodied from the prickly grasses, covered with a cold sweat, my father and brother arrived at the old shed. Immediately they froze. The concealed door was free, open, and inside – not a sign of a living person. A howling wail tore itself out from my father's breast, and my brother stood by the side, a terrible pain took hold of all his limbs.

My brother took my father by the arm and they let themselves go back. On the way they ran into their friend, the old peasant, who turned to them with a pained cry:

– Run away, as fast as you can, because tomorrow will be too late!

My brother led my father into the old shed, but not a word of comfort could he find for him.

The old peasant did not close an eye that night either. He saw the terrible picture, how wild animals had thrown themselves on the two innocent victims, torn off their clothes, and driven them through the village naked.

My mother and her 20-year-old daughter threw themselves onto the ground and did not want to move from the place, but the frenzied Gestapo men forced them with rubber batons to go on.

With the mother and daughter they had already had their fill, and what further? The father is already too weak to run away, and the son will not leave him alone.

The old peasant searched for some way to save his poor friend. In the meantime the night passed. The next morning the peasant did not go to work. He told his household that he did not feel the best and he immediately began wandering about [as if lost] by the shed. Something of a premonition told him to stay nearby there. He saw the murderers, led by a young hooligan from the neighboring village. They all went into the shed. Apart from the two Jews, they also found half a loaf of bread and a few cooked potatoes.

– This is not a good sign, the Jews had a friend here. We must settle accounts with them immediately.

But the Gestapo men did not know the name of the Christian Jew-friend, and their wild shouts and blows did not help them. The father and the son both became mute.

After that same day, they took the father and the son to their deaths. This time, they called all the inhabitants of the village together, so that they would see how the German Reich settles accounts with its enemies.

The old peasant was standing to the side, behind a tree, and a heartfelt look from him accompanied the father and the son on their last journey. My father could hardly hold himself on his feet, but the young fellow, with a warm glance, took in the surrounding fields, gardens, and the crooked little huts. It was very hard for him to part from all this. He also saw the old friend, and sent him a heartfelt, grateful smile. Like a hero he went to his death, and also like a hero he fell from the third bullet, which struck him in the heart.

About the tragic perishing of my family I was told by the old peasant in the year 1947, when I visited Hrubieszow.

I, the only remaining daughter, ask for this to be eternalized in the yizkor book for the Hrubieszow community.

- Said a 5-year-old boy to his mother, as the Nazis were taking them to their deaths[1]

Translated from Yiddish by Miriam Bulwar-David Hay

A young Jewish doctor, who himself lived through it and managed to rescue himself out of Poland, describes the shocking scene.

– I myself was a witness to the following scene – said the doctor, who worked in the Lublin area and also belonged to the Jewish police force. The doctor rescued himself out of Poland, and his report has now, through a neutral country, been received by the World Jewish Congress and by the representatives of Polish Jewry in New York.

I saw it myself in Hrubieszow. As a clerk of the police force, I was forced to go together with a German gendarme as escorts of a group of Jews whom the Nazis were deporting from the town and were dragging to the train. I heard how a 5- or 6-year-old little Jewish boy calmed his mother, who was crying bitterly, saying to her:

– Mother, we are going to death, let us be brave like lions, so that they do not see that we are frightened.

The rescued Jewish doctor described the mass deportation of the Jews of Hrubieszow and the nearest surrounding towns.

– I myself lived through the terrifying events in Hrubieszow. The mass deportation and the murders in Hrubieszow happened on the 1st and the 2nd of June, 1942.

On the 1st and the 2nd of June, on the order of the Nazis, there had to report in Hrubieszow all the Jews from the town and from the surrounding little towns: Grabowiec, Bełżec, Uchanie, Horodło, Dubienka, and Strzyżów. In total the count of Jews who came in to Hrubieszow from the area reached 9,000 people. In Hrubieszow alone, 7,000 reported. All together, the Nazis drove together in Hrubieszow 16,000 Jews, and out of them, after the mass deportation and murders, there remained 4,000 people. Out of that number, 3,000 were from Hrubieszow. Everyone had to report, even the Jewish workers who worked [directly] for the Germans. The Nazis first of all deported the children, women, and elderly population, who had been ordered earlier to assemble at the market.

Daily they deported from the town around 2,000 people, always at night. On the way to the train, the Nazis killed with revolvers those who walked slowly, the weak, sick, and exhausted. Whoever did not follow the order to go into the wagon – fell from a bullet on the spot.

The sounds from the parents, when they saw how they were killing their children, I will never forget.

After that, when they had dragged a group of Jews out to the market square, they searched through their homes from the cellar to the roof. When the Nazis found Jews who had hidden themselves, they tied the hands of the unfortunates with barbed wire. The crying of a child often uncovered the place where they had hidden themselves.

I knew two Jews who lay for nine days in the Rabbi's ohel[2] in the Hrubieszow cemetery. And they saved themselves, not to mention that just a few steps from that place Jews were being shot who had earlier hidden themselves in their houses. After searching through all the houses, the Nazis dragged out around 300 Jews from their hiding places and brought them to the cemetery, tied their hands with barbed wire, in groups of five people. I was there together with them, as an official from the police.

The Nazi murderers began catching the small children by the feet and with one bestial blow smashed their little heads on the gate of the cemetery. The cries of their parents, when they saw how their children's brains were spraying out, I will never forget.

After the children, came the turn of the men. They told them to lie down on the ground, five men at a time, as they were tied up, with their faces to the ground. Whoever tried to resist was cruelly beaten. The Gestapo murderer then stood himself on the corpses of the unfortunates and shot them with a machine gun. After that the second group of five tied-together Jews had to lie on the first group, and had the same horrible fate. When it became too hard for the Nazi hangman [executioner] to climb up on to the too-high mountain of the dead, he told the new group of victims to lie down in another place.

The last to be killed were the women. Why did the unfortunate women have to be sentenced first to see the ruthless murders, before they themselves were to be killed?

The deported Jews from the little towns around Hrubieszow were dragged by the Nazis to the death camp in Sobibor, because Bełżec was then overflowing. With the same cruelty the Nazis carried out the deportations and murders against Jews in Krasnystaw, Piaski, Izbica, Trawniki, Kamień, Rejowiec, Biłgoraj, Janów Lubelski, Chelm, Zamość, and other cities and towns of the Lublin district.

– Australian Jewish News, March 3, 1944.

Translator's Footnotes:

Translated from Yiddish by Miriam Bulwar-David Hay

|

The village of Treblinka, Here one hears a blockade, And here one stands in the rows, For a small spoon of marmalade.

The son searches for his mother,

The police

Children shout to their mother:

The village of Treblinka, for all Jews the good place[1], |

Translator's Footnote:

by Yaakov Rozenblat, Avraham and Leib Lerer

Translated from Yiddish by Miriam Bulwar-David Hay

On the 9th day of the month of Cheshvan 1942[1], the third evacuation [deportation] from Hrubieszow took place. They gathered together all the Jews, among them the Judenrat[2] and the Jewish police force. A few succeeded in hiding themselves, to three of them a miracle happened to liberate them: David, Avraham, and Leibish Lerer. They were freed by the deputy-district administrator of Hrubieszow, Kontok.[3]

On the second day I saw that hiding myself at Mikhael the shoemaker's, a drunken gentile, for good money is of no use. By the way, once in a while the gentile decided to drive me out of his house.

For lack of choice, I set off on the road to the brickworks. There I met a policeman and asked him to tell the Gestapo that I had reported of my own free will, that he had not found me in hiding.

From the Gestapo they sent me to work. Later were freed Yehoshua Koner, Zalman Gelerenter, and Yaakov Lerer. Every morning they led us under guard to the work, and at night they led us behind the magistracy, to sleep together with those who had been arrested.

It was painful to see how they brought in to the magistracy our brothers, who had been found hiding. At the cemetery they used to shoot them. Among them were many close ones,[4] who will remain forever in my memory.

After that the police caught Yankel Brand and Rabinovitch with their family and brought them to the Gestapo, behind the magistracy. When the murderer Evner, who is responsible for shooting thousands of Jews, saw Yankel Brand and Rabinovitch, he asked them:

– How do you come here? I had already locked you in the wagon that went away to Belzec, next to Tomaszow.

They told him that they had forgotten the money and diamonds that remained from the Judenrat. After he took away their belongings, the murderer forced them to bring together all the Jews who had hidden themselves, about 370 people. They led them away immediately to the Barracks, where waiting for them was a large grave, and they were shot there. Freed were only the families: Brand, Rabinovitch, and Orenshtein.

Soon after that, in accordance with an order from the murderer Evner, a group was formed with the number 1, which worked for the Gestapo. It is understood that everyone wanted to be in group number 1.

After that, a second murderer, Vagner, formed a group number 2. A third murderer, Oleks, formed a group number 3.

It did not take long and they ordered group number 2 to stand themselves in a square with ropes and shovels. They led them away to the cemetery and shot all of them.

The Gestapo assured us that there would be no more shooting. A few days later they shot Yankel Brand and Rabinovitch. Doctor Orenshtein then took over the leadership of the camp.

One fine morning an order came from the Lublin Gestapo that they should send a transport of 57 Jews to Majdanek. There they all perished.

In that time they dug out a large pit at the cemetery and the murderers gave the pit a name, “The Bath.” We knew that when we would finish the work in the Gestapo they would lead us all away to the pit.

One fine morning they brought us to the magistracy, searched us from head to foot, and led us away to Budzyn[5], next to Lublin. That was in September 1943.

And that is how we remained alive, after we saw death in front of our eyes.

Translator's Footnotes:

by Yitzchak Landsberg

Translated from Yiddish by Miriam Bulwar-David Hay

In the Hrubieszow ghetto there were in the year 1941 there were around 14,000 to 16,000 Jews. We worked on the railroad and at metal punching jobs.

In the year 1942 there were three aktzias[1]. Four thousand Hrubieszow Jews were brought to Sobibor and were burned there. Three thousand were killed in two aktzias in Bełżec, next to Lublin. At the end of 1942, the ghetto in Hrubieszow was liquidated.

After the three aktzias, the remaining Jews spread themselves out in villages. I was fortunate and fell into a group that was released into the ghetto and worked for the Germans.

At the beginning of 1943 they brought us to Majdanek, next to Lublin. Five weeks later they took us to Plaszow, next to Krakow. There we were 3,000 to 4,000 Jews. From there they deported us to Wieliczka and after that to Flossenburg and Hersburg[2] in Germany. Eight hundred Jews and 4,000 [others] of assorted nationalities; we worked at tunnel work.

In January 1944 I became sick and I was brought to the hospital in Flossenburg, where they beat me murderously instead of healing me.

In April 1945 they evacuated our camp. Fourteen hundred men perished during that horrible March, during which the Americans liberated us.

We [Jews] were left two hundred.

| Tragic dates:

15 June 1942 - The ghetto in Hrubieszow is formed. In the aktzias of June 1942, 5,500 Hrubieszow Jews perished. |

Translator's Footnotes:

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Hrubieszów, Poland

Hrubieszów, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 25 Sep 2022 by LA