|

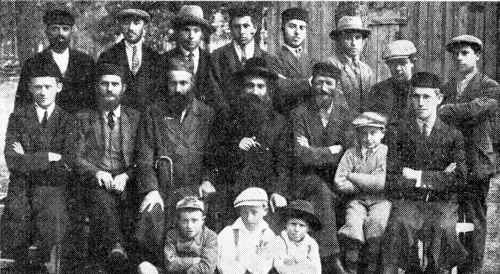

Seated: Yankev Herman, Shmu'el Leyb Herman, the visiting rabbi and his synagogue manager, A. Zilberberg, Moyshe Herman

Standing: Young members of Agudas-Yisro'el

|

|

[Columns 241-242]

by Borekh Dovid Tsimerman, Bnei-Brak, Israel

Translated by Yael Chaver

|

|

Seated: Yankev Herman, Shmu'el Leyb Herman, the visiting rabbi and his synagogue manager, A. Zilberberg, Moyshe Herman Standing: Young members of Agudas-Yisro'el |

Our town, Hrubieszow, was on the border of one-time Austria, Russia (Volhynia), and belonged to Congress Poland. This was reflected in the Hasidic movements in town. Thus, for example, the Austrian influence was felt in the Ruzhyn Hasidic group (Czortkow-Husiatyn) and that of Belz; the Russian influence was noticeable in the Chernobyl group (more recently Turisk), and Polish Hasidism through the Kock- Radzyń group.

Influence in the Town

During the period of the Turisk preacher, Rabbi Avrom (may his memory be for a blessing), the entire town was under his influence. Nothing happened in the town without his approval. Whether there was a search for a rabbi, a ritual slaughterer, or other religious matters, he needed to be consulted first. After his death, his sons assumed the leadership. One of them, Reb Yankev Leybele, assumed the title of the Turisk Hasidic leader; and another, Reb Motele, was the Kielce-Kuzmir Hasidic leader, author of the book Ma'amerei Mordekhai.

During their time, the influence of Turisk waned, and the other Hasidic factions now had the right to speak up. Thus, for example, the ritual slaughterers were divided among the Hasidic groups. With the exception of Radzyń, each faction had its own slaughterer (the Radzyń faction may not have had a slaughterer due to the sin of the techelet).[1] Though the cantor of the main synagogue – Reb Motte Khazn -- was a Radzyń Hasid, he had to lead the service while wearing a tallis with no techelet.

Education During That Period

While the Turisk preacher was active, as well as later, the foundation of education was the cheder. When a boy turned three, he would be wrapped in a tallis and taken joyfully to the cheder. At age five, he began learning Chumash.[2] That was the occasion for a party, which each family held according to its capacities. Seven-year-old boys began studying Talmud, and continued until their bar-mitzvah. At that age, children were considered capable of studying on their own. They then joined the Hasidic synagogue, which was the main source of education for boys, until they married – except for boys who were incapable of study, or were constrained by financial circumstances. Such boys left synagogue study at age 15-16, and learned a trade or became shopkeepers.

The Hasidic synagogues were full of younger and older unmarried men, as well as young husbands supported by their in-laws. Thus, an observant Hasidic generation was able to develop. This was the case in all the Hasidic synagogues; and primarily in the Turisk synagogue.

The Rise of Agudas-Yisro'el

At that time, there were very few Jews who were concerned with their sons' education. The process was automatic: first to cheder, then to the small synagogue. The only concern was how to obtain money for tuition until the child began studying in the synagogue. Besides studying, the young men in the synagogue were also busy repairing sacred books, and helping to support poor families. They would go out into the community and collect money for this purpose, giving openly as well as secretly.

This tradition continued for many generations. A profound change occurred at the time of the two major events during World War I: the Balfour Declaration, and the Communist revolution in Russia. Masses of young people left the synagogues. A large proportion adopted Zionism, and others adopted Communism. The Turisk synagogue was completely emptied; the sounds of the Torah grew faint. The sound of study in the Husiatyn synagogue was hardly noticeable, and flickered until it was virtually extinguished. Various organizations now took up community work.

It was at this moment of catastrophe for religious observant Jews that we hatched the idea of joining Agudas-Yisro'el and so save what could be saved.

In the Attic Synagogue of Yudele the Slaughterer (may his memory be for a blessing)

Reb Yudele the slaughterer (Shtokhamer) – may his memory be for a blessing – was a Czortków Hasid, who prayed in the Husiatyn synagogue, where both Hasidic groups prayed. He was an astute scholar, a devout Hasid, and extremely humble. He did not emphasize his own personality, but devoted his life to others. He raised his children – three sons and two daughters – in the same spirit. His elderly father, Reb Volakh, was part of the family. The Hasids would say that not only Reb Yudele and his sons should be respected, but even his daughters, whose scholarship was almost equal to that of his sons. His home was open for celebrations, memorial gatherings for a deceased rabbi, new-moon celebrations, or a simple kiddush on Saturday after prayers – they all took place in the house of Reb Yudele.

I recall that one Saturday before kiddush Reb Yudele sent for his neighbor, a tailor who was his synagogue manager. When the neighbor came in, Reb Yudele greeted him effusively, as was customary with important persons. The neighboring tailor responded,

[Columns 243-244]

“Reb Yudele, why are you making me so important? You're so much more important! After all, I'm a tailor and you, Reb Yudel, are a ritual slaughterer.” Reb Yudele answered, sincerely, “You should understand, Reb Dovid, you're a tailor who cuts cloth, and I'm also a tailor – who cuts chickens. But your life is better than mine; you cut a piece of lifeless merchandise. You know what you're cutting. I, on the other hand, cut a living thing, and who knows what type of soul I'm cutting|? So, tell me, aren't you more honorable than me?”

His home was open to the needy. Every poor man knew that he would receive a bowl of soup at Red Yudele's house. He himself, however, lived frugally. His home was also the cradle of Agudas-Yisro'el. The first organizational meeting was held there. For a long time, his attic synagogue was where the young people gathered, divided into two groups: young Agudas Yisro'el and Po'alei Agudas-Yisro'el. The attic also housed the Sifriya library.[3]

Agudas-Yisro'el in Our Town

When the religiously observant population of the town was organized as Agudas-Yisro'el, a council was elected. Reb Yoysef Zilberberg was the chairman, and his first – and main–mission was to revive the small synagogues.

Those people who remained faithful to the synagogues gathered around Reb Yudele the slaughterer. As a result, the Husiatyn synagogue became the center, at which the young Agudas Yisro'el members studied a page of Talmud every evening.

We also saw to the education of boys and girls. A Talmud-Torah was established, which gave children from poor families a chance to study. Much dedication was needed in order to maintain the Talmud-Torah, which was always drowning in financial deficits; Agudas-Yisro'el was its steadfast supporter. At one time, there seemed to be no chance of keeping it going. The Talmud-Torah was threatened with closure. That was when Reb Zundele (Shapira) –a grandson of the Belz Hasidic leader–donated the dowry that he had only recently received, to keep the school open.

The curriculum of the Talmud-Torah included not only religious studies, but secular studies as well. They wanted to name it Yesodey Ha-Torah (like all the Agudas-Yisro'el schools in Poland), but some Hasids opposed the suggestion, and the idea was removed from the agenda.

Boys studied Hebrew until they were 13 -14, when they were capable of really understanding a page of Talmud. Most boys went off to study in Yeshivas, or remained in the synagogues. In recent years, a Yeshiva named Beys Yoysef was founded in our town. Now it was not only our children who did not have to go away to study, On the contrary, boys from the towns in the vicinity around Hrubieszow would come to study, and were provided with hosts who hosted them for meals. Our Jews considered it a good thing when a Yeshiva boy came to eat a meal with them.

In the last year before the war, a circle named “Flowers of Agudas-Yisro'el” was founded, comprising students from the Talmud-Torah aged 11-14. They met in the Young Agudas-Yisroel's club space (on Lubelski St.) and heard lectures on the essence of the organization. In their free time, they completed the education that they had received in the Talmud-Torah. The young generation flourished, and we had hopes for a fine future for religiously observant Jews. They would gather every Saturday night, initially at Reb Yudl the slaughterer's house, and later in the house of Mrs. Khane-Goldele Shapira-Rokeakh (she was called “the Rebbetsin”).[4] Their last location was in their own place on Lubelski St. They would spend the night enjoying the end-of-Shabbat meal, singing beautiful Hasidic melodies. Yankev and Motl Herman would moderate the ideological conversations.

Many members participated in settler training courses; among them were Motl Herman (in Kraśnik), and Dovid Moyshe Shtokhamer with Moyshe Eli Gelernter (in Łódź). The brothers Yoysef and Yitskhok Erlikh participated in the Warsaw educators' seminar, at 6 Twarda St.

We Establish a Bais-Ya'akov School[5]

Agudas-Yisro'el was concerned not only with the education of boys, but with educating girls as well. In spite of the heavy burden of maintaining the Talmud-Torah, Agudas-Yisro'el took on the even more formidable task of opening a Bais-Ya'akov school for girls. Yitskhok Me'ir Shapira (the son-in-law of Moyshele Bukhtreger) took this mission upon himself.

The Talmud-Torah suffered from a chronic lack of funds, but supporting the Bais-Ya'akov school was even more difficult. A considerable proportion of religiously observant Jews opposed the plan, fearing that educating girls countered the precepts of the Torah. They quoted the sages: “Anyone who teaches his daughter Torah is teaching her promiscuity.”[6] Shapira, a young man who was fervently Hasidic, was also devoted to everything related to Judaism. He understood the significance of the project. Along with the council, he opened a Bais-Ya'akov school for girls.

The school examinations made a strong impression on the town. Even the school's opponents admitted its importance. I remember the day after the first examination, at Purim, when the school was the talk of the town. “Have you heard?” said one man to his acquaintance, “I would never have believed that such young girls could learn so much Torah and laws in such a short time. I think they know almost as much as the boys. The Kraków Teachers' Center really sent us good teachers.”

The Bais-Ya'akov school suffered from high expenses and low income from its members. This was the situation until World War II broke out, when the Hitlerist beast decimated everything.

May God avenge their blood!

Our sorrow is too near, our pain is too great, and we cannot mourn. Summon the wailing women![7]

Translator's Footnotes:

by Mordekhai Luxenburg, Herzliya, Israel

Translated by Yael Chaver

|

|

One wintry day, the news spread like lightning: a labor union had been established in our town.

The leader was Moyshe Shukhman; he worked closely with Mitelpunkt (now living in Israel), Shmu'el Zemel, Eliezer Hudes, Mordekhai Boden, Mordekhai Apelboym, Moyshe Levit, Leyzer Soyfer, Yankev Vaysbrot, Arn-Shmuel Lerer, Heni Kirshner, Toyve Nisel, Miriam Groy, and Sheve Radomski.

The first action of the union was shortening the work day and increasing the wage. At that time, many workers were still working seasonally, without contracts. The workers' demands were: 1) Recognition by the union. 2) Hiring and firing workers with the union's knowledge. 3) Decent treatment. 4) An 11-hour work day, 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. with one hour's break. 5) Wages paid every Friday. 6) Paid holidays.

Meanwhile, May 1, 1918 was approaching. The union leaders organized the members for a general strike; at that time, it was forbidden. However, we disregarded the prohibition and went on strike on May 1. All the workers arrived at the union office dressed in their finery. Some wore army shoes, others the brightly colored uniform of a military unit. The women wore skirts and blouses made out of colored canvas sacks.

We gathered at 9 a.m., and decided that everyone would go to the Brodice grove. In small groups of three or four, with red ribbons in our lapels, we scattered in the grove, and spent the whole day dancing, singing, and enjoying ourselves. At evening, the entire group marched to town in orderly rows. When we came to the oil orchard, we began shouting slogans: Down with war! Down with militarism! Down with capitalism! Long live the Jewish workers's Bund![1]

Austrian police were stationed to the left, near the meadows. The guard, Suriner, came out holding a lamp, to see who was shouting. A group of members quickly approached him, including Avrom Fayfer, Me'ir Zak, and Shimen Dovid Shapira, and took his lamp. We continued marching loudly across the wooden bridge to Panska Street, shouting out revolutionary songs. When we came to the pharmacy, near Perel Kenig's inn, a group of policemen was waiting for Moyshe Shukhman. They grabbed his hands and feet, and wanted to throw him in jail, which was then located in City Hall. But our comrades Mordekhai Boden, Mordekhai Apelboym, and others, stood fast, like a wall of iron. After a short battle, the police had to yield and free our comrade Shukhman.

Singing revolutionary songs, we marched to the union office, which was at Yidl Daytsh's, on the church square. After hearing a short, peaceful talk by Moyshe Shukhman, and singing the Bund's anthem, the demonstration ended.

Translator's Footnote:

Translated by Yael Chaver

|

1, I've been standing here for weeks and months, Here, in the streets, thinking about everything.

2,

3,

4,

5,

6, |

by Y. Saler

Translated by Yael Chaver

The Jewish artisans in Poland suffered from many problems: strong competition, high taxes, and quite a lot of anti-Semitism.

In 1928, Pinkhes Saler, Yitskhok Shimen Fayfer, and Sender Ayzn decided to establish a socialist artisans' union. A bourgeois artisans' union already existed, the so-called “Rassner Union.” We assembled 60 artisans in the synagogue, and elected a leadership that comprised Pinkhes Saler (Chairman), Sender Ayzn (Secretary), Yoske Vaysbrot (Treasurer), Yankl Rayss, Avrom Fayfer, Ber Shtern, Mordekhai-Itshe Vaysbrot; Dovid-Leyzer Glezer, Avrom Boden (Oversight Committee).

Each of those assembled contributed one złoty a month. However, the town governor would not grant the union legal status. As it happened, Yitskhok Shimen Fayfer did some bookbinding for the governor, and convinced him to legalize the union. Tailors, shoemakers, carpenters, glaziers, bootmakers, and other artisans now had the support and help of the union.

The “Rassner Union” charged 30 złoty for membership; the socialist union did the same for 10 złoty. This attracted more people to the Socialist Artisans' Union, who came from the surrounding province as well.

The union's activity spanned so many areas that it needed a special person to coordinate activities. It hired a paid secretary – Dovid Bornshayn. In 1936, the tailors who worked at home went on strike against their employers, demanding that they be paid every Thursday rather than waiting for weeks or months. The strike included thirty families, and lasted for six weeks. Naturally, the union supported the strikers, which helped influence the employers.

In 1938, the People's Fund received a sum of money to help artisans. Loans could amount to 200 złotys. However, the anti-Semitic management of the fund decided to lend only to the Polish artisans, of which there were very few.[1]

The leadership of the Socialist Artisans' Union then approached Swierzynski, the Gymnaziya teacher, who was also a member of the People's Fund and of the Radical Peasant Party. Thanks to his intervention, we were able to enable Jewish artisans to obtain loans.

These are only a few facts concerning the ramified, important activity of the Socialist Artisans' Union.

|

|

Standing: Yosele Sher (secretary), Avrom Aykhman (tailor), Hersh Soyfer (carpenter), a child (name unknown) Seated: Hersh Sher (tailor), Arn Shloyme Royter (builder), Yisro'el Shpiler (tailor); Mandelblit (hat-maker), Avrom Yitskhok (tailor) |

Translator's Footnote:

Translated by Yael Chaver

On January 3 of this year, our local branch hosted the annual general convention of the members of the Socialist Artisans' Union. Simultaneously, there was a report from the Congress of Artisans in Lublin, December 24-28, 1930. The convention was opened at 7 p.m. by the Council Chairman Yisro'el Shpiler. Hirsh Klingel was elected chairman for the day; he called on Hirsh Sher, Binyomin Koyfman as assessors, and on Yoysef Sher as secretary.

Chairman H. Shayn presented a report of the management's activities up to this point, and demanded that all members take their examinations as soon as possible.

The report was recognized by all those present. At the proposal of Moyshe Frumer, there was a unanimous vote of thanks to Comrade Shayn for his untiring work as chairman, and a wish that he continue leading the union.

Secretary Sher presented the Fund's report, which was acknowledged.

Elections took place, with the following results:

Leadership: A. Shayn (chairman), Y. Shpiler (deputy), M. Frumer (secretary), Y. Rokhman (treasurer), and B. Eylboym.

Council members: Noyekh Aykhenblat, Y. Kornblit, A. I. Koper, Y. Mandelblit, N. Alter.

Oversight committee: Genya Alt and N. Alter.

At the conclusion, we stood at attention in honor of our recently deceased member Henye Brazberg.

Hrubieszower Lebn, No. 2, January 1931.

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Hrubieszów, Poland

Hrubieszów, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 17 Sep 2022 by LA