|

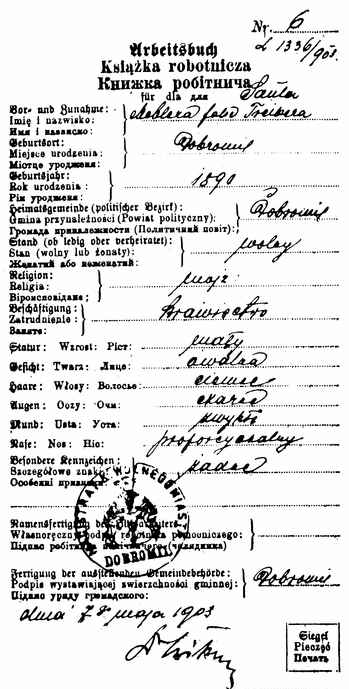

May, 1903 with signature of Dr. Zwicklitzer, Mayor

|

|

[Page 37 - English]

Apprentice Years

I went as apprentice to become a tailor. This doesn not mean that I was not already earlier sewing on a machine with my mother from nine years on, helping sew peasant children's dresses and aprons, and from time to time also helping sell the finished goods to the peasants. Once, in August 1899, one “Shabbos” night after “Havdallah” we both sat down to two machines (we had two Singer foot treadle machines) and finished two dozen little dresses and aprons. About two o'clock in the morning Mother escorted me out of the house with the pack of finished merchandise and sent me off to my father, a mountain walk of three and a half European miles. I arrived at the place of the market fair, (called the Clavary, a place where religious processions were held) when it was already broad daylight. I asked my father what time it was and he answered “six o'clock”. First thing Father led me into the kretschma (tavern), first to “daven” and then to feed me breakfast.

Then my uncle Yusha conferred on me the honor of standing in charge of a keg of cider. Meanwhile there arrived a peasant procession bearing an image of the Virgin Mary, an elegantly decorated stature on a red velvet littler. I am standing crying out “Cold drinks, cold drinks”, oblivious that it was an improper time, so a hefty peasant set his boot on the faucet of the keg and the drink began to run out. I bend down to close it and someone hoisted my cap with a stick and there I remain standing without a hat, bareheaded just when they carried by the Virgin Mary and all their crucifixes and their other sanctities, accompanied

[Page 38 - English]

by a handsome barrage of blows by peasant staffs on my head. I barely escaped to my father's stall and about eleven o'clock reached home again. That “Shabbos” at the “davenin”, I “bentshed goimel”, offered up thanks for my deliverance from that peril: so I was advised by the older folks, to help me banish my terror.

As I began to relate earlier, I was entrusted to a tailor, Itzik Schneider, a ready-to-wear tailor, actually kinfolk, the husband of my mother's aunt, sister to my grandmother. They treated me worse than if I had been a total stranger. Two years I worked with this family. Itzik was not interested in teaching me the trade. I received no pay, only occasionally Friday after the sweat-bath he would give the journeymen a spot of brandy with half of a fresh baked roll, so I would get that too.

I used to have to go on foot delivering the ready made merchandise to the dealer, bring the loads of unfinished wool cloth from that store to be worked up into men's mantles and coats. Here I want to tell of three events.

Once on a very bitterly cold day, they sent me to bring the raw materials. Nu, much choice I had. Warm gloves—I had none. By the time I had gone half way Ifelt as if the nails would spring off my fingers. What to do? The snow is deep. There is no place to sit down to warm my hands. I shift the load from shoulder to shoulder. Half frozen I barely made it back to the cottage. It took a bit of time till I could thaw out my hands. For this all that I earned was the pickings of the cotton padding waste which they used in the peasant cloaks. All week I collected this and sold it to the hatmaker for two greitzer.

A second incident. On a winter night, slippery wet, so dark you could grasp the gloom in your hands, my boss, the “relative”, takes five finished cloaks, with light colored linings, piles them on my shoulders, not tied together. I go out half a block and crash. I slip and fall with these light lined mantles into the muddy slush. Nu, I just about made it back with the coats. “Meila”, you can figure for

[Page 39 - English]

yourself the “Shir Ha-maalos” song and dance that master of mine gave me[53].

Another thing that happened to me. The pressing irons used to be heated over a coal fire, and we needed live burning coals to ignite the hard coal. So the master sends me to the baker's to fetch a few hot coals. As I go outside a fierce wind whips up the sparks and live burning embers are sent flying over the alley. The neighbors see and begin to scream. Then I was really frightened, try to open the pressing iron to shake the coals into the gutter, whereupon the wind first really began to scatter the sparks. The neighbors chased after me wanted to kill me for trying to set the town on fire. Finally the few embers burned themselves out and I was rescued from death.

Since too much I was not learning of the trade, I resolved that if I was to become a decent craftsman, I must go to learn from a custom tailor. It was just before Passover that I earned some money at baking matzos, and saved up for a spring topcoat, made at a custom tailor's. So I indentured myself there for three whole years.

That will take a bit of telling, and here I want to digress to recount an episode from which a major catastrophe might have developed for the Jews of Dobromil. As you recall, the Jews of Dobromil as in other Galitsianer shtetls eked out their living by “luft parnossas”, (making a living from the air). In all of these “parnossas”, the women had to help in order to have a piece of bread. I once learned an item of Oral Torah Tradition that in Jewish legend it is told how it was because of a hen and a rooster that the Holy Temple went up in flames. Here in Dobromil a similar fate might have come about over a little apple.

In Dobromil there was a little space, half a square, where women used to sit by their fruit stands. Very few people understood buying fruit by the pound. They simply didn't have enough money, or they did not indulge themselves to buy several pounds of apples or other fruit, unless the fruit was already half rotten, although the whole region was flooded with fruit orchards. One ordinary fine Monday morning “Yeeden” and “Yeedenas” busily set up their

[Page 40 - English]

stands, each with their produce, both raw and finished. The peasant folk streamed into town with their horses and wagons, their hogs, their cows and calves, hens, ducks, geese. The weekly market was under way, with its appropriate screaming and tumult, like all weekly market days. “Yeeden” were calling out with hoarse voices, each calling customers to his stall, announcing that he has the best wares. So they did some selling, took in a little cash, and presently it was tending to the end of the day. The peasantry were packing up their purchases to ride home.

One peasant couple came over to a Jewish girl to buy some fruit, apples. We had the custom of the baker's dozen: with every purchase the customer got a “pshetschinik” (Polish: przyczynek), an extra fruit. Otherwise it was no bargain. The girl had already added the extra to the purchase, in this instance, but then it was when it all happened. The peasant woman took one more extra apple. The girl, not using the best judgment, tried to snatch this apple back, and accidentally caught her fingers in the woman's string of beads, which scattered to the ground. A hullabaloo broke out. The peasant grabbed the girl by the hair with such violence that he pulled out tresses, scalp, skin, and all. A riot followed between peasants and “Yeeden”. Our uncle Hersh, may his memory be blessed, was then in the prime of young manhood and he swung into action with the leg of a stool, and he also did not kid himself, he collected his quota of blows. Whoever was there both gave and got, each his share, until the police arrived. The peasantry simply took to their heels and fled homeward. Only the “Yeeden”, being local town residents, remained. So the police filed an indictment and summoned the “Yeeden” into court on charges. A number were subjected to punishment (detention) for causing disorder in town and giving the town a bad name. Others got off with money fines. Many were simply discharged.

The Jewish girl who suffered the most, in pain and in shame, till her head and hair healed up, sold no more apples for a long time, trembling in fear lest something should again happen because of her. And so the Jewish

[Page 41 - English]

shtetl of Dobromil got off with only a few blows and a little fright. The fright continued for quite some time. We anticipated an organized pogrom on the part of the peasant folk. From that Monday on the town authorities used to send in the gendarmerie every Monday, with guns and swords, to guard against any attack on Dobromil, and so thereafter none such took place.

[Page 42 - English]

More Apprentice Years

And now another installment of tailor's tribulations which I endured in Dobromil. As you recall for all of two years I was tormented at the ready-to-ear tailor's and learned almost nothing except to lug the loads of uncut cloth from the cloth dealer or the finished cloaks to the store who sold to the peasants. Now I had decided that this was no way for me. I must learn to be a proper craftsman. I talked things over with Dad and Mom and they acceded to my justified complaints. Father took the mission on himself and went to speak to that same tailor by whom I had a very fine black spring coat made to order. In “Chol-hamoed Pesach” (the middle days of Passover week) he indentured me for three years, a year and a half to eat at my home, and the second and a half to eat at the tailor's. They were a father and son partnership, as it stands in the Scripture verse, a schneider ben Schneider, a tailor son of a tailor. My new boss had never taken an apprentice before. To my miserable luck, he agreed and bade me come in after “yomtov” to start learning.[54]

Three years, heavy-laden years. First thing my boss did not like was the way I held my fingers bent with the thimble on the middle finger of the right hand. So he tied up my finger for four weeks time till I could not straighten it out again and yea verily even unto this selfsame day I have that finger bent as if I were ready to push a needle. Second, it was my chore to thread needles for the boss, since he was an old man and could not see to thread a needle so fast. So I stood and did that for him. A third task

[Page 43 - English]

imposed on apprentices was to go on miscellaneous errands. It was usual to plug every hole with me. Although they had a boy of their own, I was the servant. Yet one other sphere of work was assigned to the learning apprentice, carrying out the family “potty” every morning, and Friday afternoon polish the shoes and boots for the whole household. This lasted almost through the whole time of my learning apprenticeship. The one chore which I did like was to deliver the finished garments, because sometimes I got a few greitzer as a tip, but in this I also had a partner, the boss's son. As it happened, he was a good fellow and used to act friendly to me.

I almost forgot. In Dobromil every employee had to obtain from city hall a workbook and give it to his boss. Without a proper transfer no second employer would hire a man, and without it no worker could make a move. I had turned such a workbook over to my boss and that meant, brother, no matter how tough things might be, you must take it and say nothing. Not once only did I curse the day I was born for the insults which I had to swallow, and this was without being given any meals. You can imagine how it was after the first year and a half when I had to eat there too and perforce sleep there also. By then I knew enough already to sew up a pair of cotton trousers, a pair of “long john” underwear pants (white “gatkes”) and a “Leib-tzu-dekel”.

By rights this meant that I was earning my keep, my meals. I used to take my meals in a corner under the great stove, so that the boss should not see. But if he would notice that I was not at the sewing machine, he would peer into my corner and make a sarcastic remark, “To eat unfortunately no one is at hand, but to do his job, ay, ay,” meaning the opposite.

Sleeping in. The room was about six to eight meters long, three meters wide. This was the workroom where five and sometimes six workers were employed. This was also the bedroom where six to eight people slept. This was also the dining room. Here too was the bake oven where the “balabusta” (boss's wife) baked bread and “chaleh” and did

[Page 44 - English]

all her cooking. And now are you anxious to know where I slept? On the topmost outer level of the oven, with a closed window through which I could see when it was dawn. Fridays I had no need to look. The “balabusta” would rise early to bake “chaleh”, and when she fired up the oven what do you think? My mattress was a sack stuffed with husks of groats which heated up fast. And small wild life, both brown and white, were also not lacking. So to get away alive I had to meekly (“bimchilah”) creep down and so anyway set down to work, even when it had been two in the morning when I had crept up the chimney to sleep. This house was so overrun with (unmentionables) that my own parents would not let me stay over a night to sleep with the. Once each week I would go to the sweat-bath and hang my underwear up to fumigate them a bit.

Nu, how does it strike you, to persevere through three such years? One had to be of iron. By the time I had finished out my three years, the older boss was already in the world-to-come and the younger bosses (who had at times looked into the “Naprzod)) taught me a proper accounting. For having been sick sometimes, for the Sabbaths and Holy Days and for several occasions when I fled from them when I could no longer endure their torments, they added a bill of debts with a total balance of six months to work off. And I was compelled to work them off.

Yes, something had happened. I was already able to make a little vest also. One Friday I was finishing a vest and they had not given me any facings. I had to scrounge up scraps for facings. If it is someone's destiny to have “tzuros”, don't ask, they come to hand. I went over to where some odds and ends, tiny scraps were lying and the Evil Impeller (“Yetzer Ha-Ra”) slipped what I needed right into my hand. I finish my piece of work, with great pride hang it up, polish everyone's shoes and go to the sweat-bath. It was already twilight. Come my boss's son into the sweat-bath, hunts me down, and says, “Shoyl, I don't know how to help you, but I have to tell you, you

[Page 45 - English]

cut up the facings of the jacket ordered by the Town Recorder, no more and no less.” Everything swam in front of my eyes and I passed out. Some one doused me with a bucket of cold water. I come to. It is already dark. I dress, go to “daven”, go home, that is to say, to the tailor's table. No one looks at me, while I go through the “Kiddush” (ritual of blessing the wine) as if the greatest calamity (“chalilah”) has befallen me. I try to eat but every morsel gags me. I see the looks I get, looks to kill, to annihilate, to efface.[55] There is a hush over the house as if the most awful wrath of God had been invoked upon them all. And nonetheless they would be able to obtain the same material, and indeed they did buy it. And I also paid for the damage, but yet I was not finished. Sunday morning I rise up, sit down to my work. One of the two brothers, the one who considered himself as more enlightened, glared at me with his eyes without saying a word and handed me a gift of his fist and into my face so that I fell off my stool with the blood pouring from my nose. The second brother mumbled something but I no longer heard anything. I picked myself up, rinsed off my bloodied face, took my “tefillin” bag and fled, not caring to wait for anything else and so ran off to the synagogue to “daven”. O did I “daven” that day, full of arguing complaints to the Master-of-the-Universe, and definitely on the spot resolved to wind up the situation. I took off the “tefillin”, put them in the bag, and took the road to the railroad station. There were lined up the coachmen, one of whom was a kinsman of mine, rather an intelligent fellow (he is here in America now, if still alive, in Brownsville, Brooklyn), and he spoke to me in this manner of language, “Shoyl-brother, you are not some kind of dope. Where will you go? You have no money; you have no workbook. Even if you reach some place on foot, the police will bring you back. Listen to me, come sit up here in my fiacre, make believe that nothing has happened, go back until the time when you will be legally free and then you can go travel wherever you will wish.”

[Page 46 - English]

I understood my bitter plight, took my kinsman's counsel and turned back to town, wiped my lips, went back to the tailor's. Although the master's wife called me to eat, I did not go to the table. Who could eat at such a time? But riding in the coach I had decided one thing: once for all I must recover my workbook. And so it actually came about. I bided my time until a summer evening when no work was being done, but I casually arranged to have some overtime work. All the household were away “davening Mincha-Maariv”, and the mistress of the house was in the street. I knew where the workbook was kept. One, two, three, the workbook lies in my shirtfront. I rushed through my overtime work, slipped home to my parents, and hid the workbook in a cradle in the woodshed. But that was all for nothing. My bosses noticed that the booklet was missing, asked me if I knew where it was, which I naturally disclaimed. That face-slapping boss then applied to the municipal recorder and obtained a second workbook, which I still have with me to this day.

At the end of the six months in which I had to work off all the Sabbaths, holy days and days of illness, I had to anew indenture myself for one year, because there was no other tailor-employer available in Dobromil except in ready-to-wear, and for this I was not considered trained. I had no choice. At this time they would offer me no more than twenty-five gulden for the year, besides meals, and I was unwilling to remain with them. The old boss's wife came after me and said “I will give you five gulden more from my money, so stay for the year.” So I remained a year for meals and thirty gulden promised me. Later from America I sent the “balabusta” back five dollars for those five gulden. And so I would up my apprentice years as a garment worker.[56]

At that time I already used to glance into the Polish newspaper “Naprzod” edited by the Social Democrat named Dashinsky. I had already begun to listen to accounts of a May Day celebration in Przemysl. At sixteen or younger I was already traipsing after Social Democratic candidates who came to Dobromil. The only place they could hold

[Page 47 - English]

|

|

| The first apprentice workbook, May, 1903 with signature of Dr. Zwicklitzer, Mayor |

[Page 48 - English]

their meetings was in a barn.[57] In my seventeenth year I left Dobromil for Berlin in Germany and never set eyes on Dobromil again.

[Page 49 - English]

I Leave Dobromil

The previous chapter ends with the words, I leave Dobromil. But that was easier said than done.

When I left the tailor shop where I had suffered all those years, there first began a new series of “tzuros” (troubles). There was no employer where I could find work. All the masters were ready-to-wear tailors and in four and a half year as apprentice I had barely been taught to make a good pair of pants for the deputy-mayor; the place where I worked was the one firm who made his clothes. Again having no choice, I took the bull by the horns and applied to another tailor who happened to have some odd job orders for “Shevuos”. This boss was called the Austrian tailor, a “Yeed” with a long and broad unkempt beard which he stroked scholar-fashion. He was short in stuture but roly-poly with a substantial pot-belly over which he draped his beard to hide his belly, because such a belly and such a beard were not befitting a tailor.

His wife was the exact opposite, small and skinny, with a pitted face probably from a childhood pox, and with a very shrill voice. Their treasure was an only daughter who had very bad painful eyes as a result of complications from childhood measles. All this I discovered promptly the first day. And chatting over the work they found out that America was in my mind but traveling expenses were lacking in my pocket. Nu, they had a ready made plan all worked out. They were ready to give me all the expenses for going to America on the one condition that I join with their daughter under the bridal canopy. So I unhesitatingly

[Page 50 - English]

lifted not the canopy but my heels. I never entered that cottage again nor returned to that job. The mistress of the house came to check up on what had happened. Plainly and flatly I let her know that I engage in no brokered marriage and would surely find my traveling expenses when I would need them.

Meanwhile in those seasons when there were no market fairs, my mother used to take orders to sew up cheap ready made men's trousers for six greitzer a pair, bringing the material from the store, sewing them up, pressed and delivered back to the store. Going around idle was no career for me so willy-nilly I sat down to one of our two sewing machines and for three greitzer a pair sewed up trousers, three greitzer properly belonging to my mother for thread she bought, for cutting the cloth, pressing and delivering.

At that time there came to town an ex-Dobromiler visiting from America. Mother invited him to our home, an invitation he gladly accepted, there not being many attractions in Dobromil. And so he did come, this guest, and finds me sewing the trousers. He expressed astonishment, and said to Mother, “Roise, in America he would lack for nothing. He is already a qualified worker, a pants operator. 'Ein kleinigkeit' (my goodness!), a pants operator”, he repeated to make sure that Mother heard what he said. I, however, was hot and cold, hot because he touched on my wishes, and cold because my whole fortune was my thirty Austrian gulden, barely enough to reach the border of Austria, never enough for ship's passage.

“The Master-of-the-Universe does not abandon us? Happens such a matter. Not far from Dobromil there exists another such creation, a shtetl half the size of Dobromil, named Chirov, and there my father had a kinsman named Chayim. Chayim used to come home each “Pesach” to his wife and children from Germany where he was a peddler in the suburbs of Berlin. Father also had kinfolk in Berlin who started as peddlers and worked up to be manufacturers and also big egg dealers. Reb Chayim even in Germany wore not only beard but also “payos” although tucked out of

[Page 51 - English]

sight. He had two daughters of marriageable age. He talked things over with my father and was willing to take me back to Berlin with him; but he wanted to meet me first. My shoes were at the repair shop. No other pair did I have. Father sympathizes with my dilemma, pulls off his own boots. I look at them. They are really too big for my feet but I pull them on, wash up, comb my hair and take off on foot to yonder shtetl. It cost only fifteen greitzer by train, but I would not indulge myself those fifteen greitzer. It was a fine day. I hike to Chirov. I arrive, am met at the door by the older daughter, about twenty-two or three, greeted with a smile and led into the cottage. Reb Chayim, a handsome “Yeed” with a fair face, a silver-streaked black beard, yarmulka on his head, sits over a rabbinical book. As I approached the table, he rose, gave me a warm handshake, and with smiling face offered me a cordial “Sholom Aleichem” (how do you do). He called Chaye, his wife, “Look, look, this is Maier's son. He wants to go to Berlin. Certainly I will take him along. He is a skilled worker, will soon make good money. But tell me, how much have you?” I tell him, something like thirty gulden. “Enough for now”, he says. “And a passport?” No. “You think you can get a passport, because you must have one to cross the frontier into Germany?”

Again I get cold all over. I am afraid, for two reasons. At that time all young men liable to military draft were held back. Second, there were good people around who only intended doing you a good turn, such as tipping off the government agencies, so that one was already cooked and well done, with no possibility of emigrating anymore. I took a pleasant leave of Reb Chayim, his wife and daughters and took the road back to Dobromil.

On the way back, all kinds of thoughts rush through my head. How to get a passport issued by the Porborcia.[58] He is actually not unfriendly to Jews, but my appearance itself would betray me. So I come home, talk things over with Mother. She covers her face with her hands, not to show tears. She understood intuitively that I was being torn

[Page 52 - English]

away from her, and she would never see me again. I comfort her; she will get a letter every week. When I am earning money, she will not be forgotten. She took her hands away from her face and with a sigh from the heart, she said, Done, tomorrow we go for a passport.

Next day at half past nine in the morning we go to the clerk of passports. We are told he is not in, away on vacation. We have to apply to the Poborcia himself. Mother does not hesitate, asks for his office and knocks at his door.. The exalted lord opens the door and asks, in Polish, what do you want. Mother seizes his hand and kisses it in the fashion of those times, and she proceeds to spin out a yarn of complaints before that person about how terrible life is with my father. She says such things about Father that I cannot understand, how can she say such things which are not so at all, plain scandalous words, and with tears to move a stone. The Lord interrupts, “Aha, he wants to go to America”. Mother swears by all that is holy that I go only to Berlin to find employment. “And he will have to report for military service to the Austrian consulate in Berlin.” Mother agrees, of course he will have to report for military service. “Have you a workbook?” he asks me. Yes, I take it out of my pocket and place it on the table. “Come back in about two days, you will get the passport, but only up to your time for military service.”

We go out into the street, mother and I, and I say, “Mama, how did you dare to say such things about Dad?” “Kind meins, my child, if I had not made it such a tragedy, you would never get the passport.”

Two days later, Friday, I went back up to the exalted Lord and an aide gave me my workbook with the permission to go to Germany inscribed. That summer, before leaving Dobromil, I enjoyed my aunt Zeesel's wedding and first after the autumn holidays, Reb Chayim and I took our departure.

We are riding to the railroad station: my father, myself, my uncle Maier Kramer who is driving the horse and wagon. (He was husband of my grandfather Reuben's sister Baila-Perl.) My mother did not go to the station. She was all

[Page 53 - English]

broken up. She saw, prophetically, that I was lost to her. Father having been a traveling salesman from his young years was not so much upset.

(There was another reason. My mother had gone through childbirth about twelve times in her life. The first born boy, Abraham, took strong fright at the sight of this world and ecided to flee hence when yet a little lad, all in all four years old. A second boy did not even want to stick it out a month, and right after his circumcision went off to the other world. Only four of us grew up. I took the place of the oldest; there was my sister Zlata, my brother Hershele and a sister Liebe Reisel, who was called Leibele, who was really a beauty. The other six infants did not even want to take a look at this world, not even to open one eye. Mother became invalided and was unable to bear live children. When I was about fourteen or fifteen, and was working on a job, late one night my father knocked at my boss's window and wakes me, “Shoyl, get up, Mama is very sick”. Then already understood what that meant and I spoke up to Father, not embarrassed to face him, “How long will this go on?[59] My boss's wife, Sara, went with us to see what could be done until the doctor came.)

Yes, we are all three riding in one wagon, and all keeping very silent. Only the whistle of the wind, the clip clop of the horses, the cracking of the whip and the “vee-oh” of Uncle Maier to the horse were heard. We come in good order to the station. I lift off my package of supplies for the trip, which included two sets of underwear, my “tefillin”, two shirts, an extra “leib-tzu-dekel”, a little soft white cheese, with two pieces of bread, a little flask of brandy and a good piece of cake. The train shuffles in. I take leave of my father. His final words to me – “Look now, don't forget the 'davenin'”-- for him the greatest worry.

I take my seat on the train, in a very depressed mood. There in Dobromil was no remaining; there where I go, what awaits me? A strange country, a strange language. I feel the tears welling up. I could really have cried plenty. Near me sits an older woman who sees my mood, and speaks to me. I hear nothing. My thoughts are far away. I

[Page 54 - English]

myself know not where. She began again, “Young man, why so sad?” Her words were like a needle to a blown up balloon ready to burst. I feel that I cannot control myself any longer and a torrent of tears fall down my cheeks. Like a mother she takes out her pocket handkerchief and wipes away my tears as I tell her that I have just taken final leave of my beloved father and mother, who knows if ever to see them again. This strange dear woman comforts me, and says to me, “Don't be so troubled, you will surely make out well.” And so the time passed, and we are already at the Przemysl railroad station, and saying goodbye.

Just as I enter the terminal building, to change trains, and there came Haman, there approaches a man with a tin badge on his cloak and tells me to open my package. I stop short, not understanding what he can find on me. I look at him questioningly, as if to say why should I open my package. He yells out at me, “Why are you standing there like a dummy, open your package!” And before I can open it, “Aha!” He already has the package spread out and he has seized the flask of brandy. He was a revenue inspector on guard against the import of liquor from other places. Nu, he had caught me in the act of a great crime, and announces, “I think I will run you in”. Meanwhile there arrived my kinsman from Chirov, with whom I was to go to Berlin. He speaks to the inspector, “Well, you really are one terrific guardian of the law. Just see what you found on the boy, a sixteenth of brandy, enough to cover a man's tooth. You have yours already, let the kid go, he's traveling with me and we have to board the train.” So with a little more hassle, my kinsman was able to bid him adieu, slipping him a coin in the hand, and we are already going into the railroad car, which we nearly missed. We had no seats for three or four hours, almost to Cracow.

At Cracow the train stopped for fifteen minutes and we went off for a breath of air. The car was jammed with people and the air was foul to breathe. We hear the whistle and hurry back to the train. Now there was more room. We took seats. It is beginning to get dark, “Mincha-Maariv” time. My kinsman stands up and “davens” the “Mincha”

[Page 55 - English]

service. So do I, but I admit and confess that “Mincha” and “Maariv” were not on my mind, and my bread and cheese I did not even taste. We approach the border crossing, Mislewicz. “Here,” says my kinsman, “we have to move fast.” So we go down to the station, our packages are inspected. Rushing, we are soon seated on the other side. Now, says my kinsman, we are on German territory. I look at him. “German” I understand, but not “territory.” He obviously understood my questioning look and explained, “German soil”.

We make ourselves comfortable, put our packages up on the shelf. This car also gets jammed, enough to make you feel faint. This is a third class carriage, my kinsman explains, where people are packed like cattle.

We have been riding perhaps half an hour, when a German railroad officer comes in and cries, “All travel passes ready”. I take out my workbook on which is written the few words authorizing my travel to Germany. The policeman takes my book, looks at me, looks at the book. I feel my soul leaving my body; they can be “meshuga” (wacky) and send me back whence I came in custody of a guard. Finally I heard his voice coming through to me, “You have people expecting you?” In a tremulous voice I answered, “Thank you very much.” That minute felt as long as the duration of the Jewish Diaspora. My kinsman came through easily. He simply showed a tax receipt showing that he was a resident of Berlin, with permission to travel.

So we ride through Germany all during the long night. I sit at the window, not sleeping a minute, just staring into the distant depths of the night. Here and there some flickering lamps flew past, some cottages, till day began to dawn. The train began to stop at every station, until about nine in the morning we pulled into Alexanderplatz station in Berlin. Dobromil was already far away. What will be?

Saul Miller stayed about two years in Berlin, and came to New York about 1909. Evenings he attended the well-known Eron Preparatory School on the East Side, mastering English, learning algebra, ancient and modern history, reading Shakespeare, Longfellow, Tennyson, as well as (in German) Goethe, Schiller and Heine. He was a garment worker all his life. As an active member of Local 9 of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, he became a top officer in the 1920's, always self-sacrificing in the interests of the workers who elected him. When factionalism split the union, he resigned office, feeling it was impossible to play a principled role. Later, when unity was restored, he was again a union leader, and served a field organizer for the ILGWU in Minneapolis, Kansas City, Baltimore and elsewhere during the years of the Committee for Industrial Organization (1937 – 1938).

After World War II he was a one-man committee of correspondence, seeking out all the surviving refugees of the Dobromil area, helping them to find new homes. For a time, when it seems possible to re-establish such centers, he organized the collection of books for libraries in Poland.

His life and his struggles were shared by his wife, Ida (1890-1958), daughter of Eliezer Loewenthal and Toba Argand, a descendant of Itzik'l Brief-trager.

He has always been a staunch spokesman for the rights of all peoples, a militant defender of the well-being of the working-class, a preacher for peace, always associated with those who were consistently principled in struggle for the liberation of humanity. To his children and grandchildren he has always conveyed the Vision enshrined in the first two chapters of Isaiah.

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Dobromil, Ukraine

Dobromil, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 2 Aug 2013 by LA