|

|

|

[Page 8]

When the first Jews settled in Dubrowa is unknown but the 1766 census recorded 406 Jews living in the town. In 1847 a post office and railroad were built and two schools were established, one for Jews and one for Russian ethnics. By 1899 the Jewish population had swelled to 1,499 or 74 percent of the town's total population. Afterwards, although the community apparently was unscathed by pogroms or violence, with western emigration the size of the Jewish population slowly began to decline.

The following account is an amalgam of the memories of several former residents of the town, recorded about sixty years after they had emigrated.

At the onset ofthe century Dubrowa was bisected by a stream. On one bank was a cemetery so ancient that no gravestones remained. Across the stream was the site of the original town where the streets were narrow and the poorer class who lived there referred to as “gassel people”, gass meaning small street. (In reality the social strata in the shtetl amounted to little more than a difference between the poor and the hopelessly poor.) Both the Bais Midrash and the shul were located on this older side of town, the latter having been built atop a hill with funds raised by Rabbi Menachem Mendel from the surrounding communities. The synagogue was completed in 1874 and was a large and imposing stone structure that according to the tradition was used for services only on Shabbat and on high holy days. Since it was unheated the congregants had to bundle up in winter, the townspeople seated in their pews and the country visitors around large tables in the rear.

On the other side of the stream the focal point of the new town was the marketplace. There the streets that radiated out from the market contained shops arid the homes of the mote well to do. This town plan was typical of most shtetla. Most business was transacted on market day which in Dubrowa was held only “now and then” because of the town's relatively small size. It was at the market that the shtetl Jew came in direct contact with the non-Jewish world of the goyim. Here there was an underlying sense of potential danger no matter how friendly and neighborly the interaction might be.

As in all shtetla, life oscillated between shul, home and market. Yiddishkeit Jewishness) and mentshlikeit (humaneness) were the two major values of the community. Emigrants from the 1920s recall that the townspeople were “united” and that the older generation were people of character with a stronger commitment to Jewish observance. Before 1900 the Bais Midrash (house of study) had been regularly filled, but was progressively less so as the new century began. Still the people retained much of their piety, respected the Shabbat and it was un- thinkable for a man to be caught not wearing his tzitzis.

Little is known of the Jewish community's early history but certainly its most prominent religious leader was Rabbi Menachem Mendel who lived until about 1895. Rabbi MendeI was considered a tzaddick,

[Page 9]

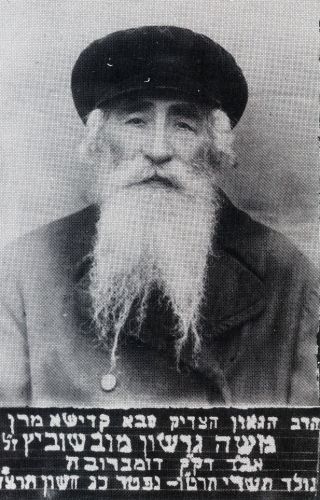

perhaps one of the lamed vav or thirty-six secret saints thought to be alive in every generation. Although tzaddikism is a term most often associated with hassidism and the name Menachem Mendel was the same as that of several famous early hassidic rabbis. Dubrowa's Rabbi Mendel was traditionally orthodox, the town being under Lithuanian anti-Hassidic (mitnaggedim) influence. It was recorded that in 1858 Rabbi Mendel was involved in work to improve health care along with rabbis from Kovno, Grodno, Lublin and Rotnitza. He was buried in a mausoleum; Jews and gentiles alike visited the site to pray for his blessing. Menachem Mendel was succeeded by a Rabbi BenYamin and then a Rabbi Pomerantz. The latter had a falling out with the kosher butchers and was forced to leave town. Then followed a competition where each week new candidates for Rabbi were screened. Finally, several townspeople took matters into their own hands, drove a wagon to the nearby smaller community of Sidra and virtually kidnapped their Rabbi Moschowitz who had been born and raised in Dubrowa. Rabbi Moschowitz was a well respected individual who remained in office as the town's rabbi from about 1910 until his death in 1932; when he was replaced by his son-in-law, Chaim Katz.

|

|

| Rabbi Moshe Gershon Movshowitz, Father of the Court (Rabbi of the town) of the Holy Community, Dubrowa. Born: Tishri 5615 (1854), died: Cheshvan 5693 (1932) at the age of 78 | |

Most of the houses were for one family and consisted of two rooms, a large one in front used as a shop and dining room by day and bedroom at night, and a second smaller room which served as bedroom and kitchen. These were partitioned by a combination baker's oven and cooking/house-warming stove forming a wall nearly to the ceiling. Most families also had a cow shed or stable and managed to acquire a cow for dairy food and a few chickens. They had little land but often an arrangement could be made with a landowning farmer whereby a Jew would provide cow manure and the farmer would prepare the land and apportion a small area for the Jew to plant potatoes and a few other meager crops. Indeed, the Grodno district was famed throughout Russia for its potatoes.

The few wealthier people had larger homes and helped the poor by donating food or clothing. Food was generally adequate and consisted of three meals daily. A cereal-like kashe soup was served for breakfast while lunch might consist of bread, borscht and potatoes. At dinner there was more soup made mostly with beans and grains. An occasional lunch provided herring, and bread and meat was served about three times a week with the soup. For Shabbat almost every Jewish household had, or was provided with, chicken, fish and challah for the traditional meal.

Jewish tradition requires bringing strangers home to share the Shabbat meal and on Friday nights the townspeople would volunteer in turn. Once when there were too many homeless Jews, one boldly asked a congregant who already had invited a guest home to permit him to come also stating that, after all, his stomach “only was the size of a seven-year-old”. His reluctant hosts were appalled to find, however, that their extra guest had a voracious appetite. When questioned about this he replied that he had said that it was his stomach that literally was the size of a seven-year-old, not his appetite! Bands of itinerant Jewish beggars were common in the 1920s and well-cared for by the townspeople. The town poor also were provided a Talmud-Torah for their children.

On occasion a travelling troop of actors would visit; once a group from Bialystok performing King Lear in Yiddish had to put on an extra performance in order to meet the popular demand. Dubrowa's townspeople were comparatively well-educated but opportunities for higher education were limited. The nearest Yeshiva was in Sucholka, the county seat, 30 km away. In the early part of this century girls did not receive formal education but learned the prayers and may have taken Hebrew or Russian lessons from private tutors. In the early 1920s, when the public school was established the girls attended too. Public school was compulsory until the age of 14 from 8:00 to 1:00 with the children studying in the afternoon at the Cheder or Talmud Torah. A few good students went on to yeshivot in Grodno or Suchovola. As anti-Semitism took hold in the schools, the Jewish community established a Tarbut Jewish Day School that was privately financed and certified by the Polish Board of Education.

[Page 11]

Graduate education was officially limited by a quota system and for professional training a Jew would have to leave the country to study in Germany, Switzerland or other European countries. As a result the town did not have a Jewish doctor until a Dr. Rosenthal in the 1920's.

|

|

| Map of Dubrowa (drawn by Abraham K. Gusewich) | |

[Page 12]

The town lacked a hospital until World War I when the Germans, responding to an epidemic of typhus, converted the Jewish-Russian school for this purpose. Very sick patients usually were sent to Grodno or Warsaw.

There was one policeman and a sergeant and on occasion the county prefect from Sucholka would ride through the district in his carriage equipped with a bell. In 1906, during the Bialystok pogroms, a troop of soldiers was stationed in the town to keep order and to watch for socialist uprisings.

The Russian government was corrupt and graft was a way of life. This included smuggling tea from Germany without paying the excise tax or, more importantly, bribing the local draft board. If an unmarried son failed to appear for the draft, his family was fined 300 rubles and if unable to pay, their possessions were put up for sale at public auction.

During the late 18th and early 19th centuries Jews were not permitted to work for the local government even in menial positions. Ironically though, all of the local government buildings were owned by Jews.

Until the twentieth century no railroad connections existed between Dubrowa and Grodno 30 km. to the east. Travel by horse cart was slow and uncomfortable and necessitated frequent stops at inns. Grodno had a tobacco industry and textile factories and was a place where girls could find employment not available in Dubrowa. Later when the railroad was built, there were two stations, Rozanistok and Kaminka, located in outlying villages respectively 3 and 5 kilometers from town. During World War I a garrison of about 15 or 20 German

|

|

| The synagogue of Dubrowa (drawn by Abraham K. Gusewich) | |

[Page 13]

soldiers was stationed in Dubrowa. One of their priorities was to keep the railroad operational and many Jewish men were pressed into labor to maintain the tracks, walking several kilometers out of town each morning and working twelve-hour shifts.

|

|

|||

| Ark of the Dubrowa Synagogue | Farming in Dubrowa, 1916. Town church is in background. | |||

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Dąbrowa Białostocka, Poland

Dąbrowa Białostocka, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 16 Jan 2010 by LA