|

|

|

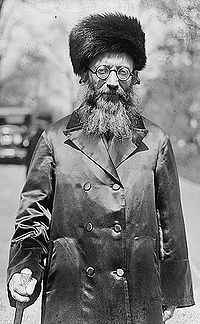

The chief rabbi of Mandatory Palestine

Rabbi Herzog and his family left for France and took the body of the deceased to the port city of Marseilles where they boarded a ship heading to Jaffa, Palestine.[1] Many of the passengers were Jewish from all over the world and attended the religious services for the rabbi aboard the ship. The ship docked at the port of Alexandria where services were held. Then the ship continued to Jaffa where the heat was unbearable, and a large crowd came to pay their respects. The body was then transported to Tel Aviv and Jerusalem to the Yeshiva Mercaz Harav where the chief rabbi of Palestine, Rabbi Awraham Itzhak Cohen Kook received him.[2] The rabbi eulogized him. The appearance of the chief rabbi of Palestine was one of last public appearances that he made in Palestine.[3] The funeral procession proceeded to the Mount of Olives cemetery where Rabbi Joel Leib Herzog was laid to rest. In accordance with the Jerusalem burial custom, Rabbi Itzhak Herzog did not enter the cemetery.

The rabbi and his entourage visited many settlements, kibbutzim, and small towns and spent most of the time in Tel Aviv, the bourgeoning city of Palestine. The city was growing by leaps and bounds. Jews from everywhere, especially from Nazi Germany, were coming to the land. Most of them had been deprived of everything by Nazi Germany but were lucky to have escaped alive. Palestine still accepted some refugees in accordance with British mandatory regulations. Most of the countries closed their borders to Jews. The Jewish Agency of Palestine placed the German Jews on a priority list of certificates to get out of Germany where their lives became hell. Some German Jews brought some capital and invested it in the development of the country. The agreement between the Jewish Agency and the German government stated that Jews can deposit their savings in a German bank that would allow the Jewish Agency to buy goods in Germany with the deposited money. The Jewish Agency would then pay to the involved Jews some of their money. This agreement helped thousands of Jews to restart their lives in Palestine. It was not easy to enter Palestine; you needed a certificate of entry that was based on a set of priorities. The conditions to obtain a certificate became harder with each year. Still, the Jewish population in 1935 reached 355,000 Jews as opposed to 65,000 in 1914.

Rabbi Herzog was impressed with the growth of the country and began to think of settling in Palestine; after all he was a Zionist. An opportunity presented itself when the rabbi of Tel Aviv Rabbi Shlomo Aronson passed away. Herzog announced his candidacy and was certain that he would be selected for the post. Opposing him was rabbi Moshe Amiel from Antwerp, Belgium. Rabbi Herzog lectured and campaigned throughout Palestine but lost the election. The vote was 22 in favor of Rabbi Amiel, 10 votes for Rabbi Herzog and 3 votes for Rabbi Solweitchik from Boston, USA.[4] The lesson was clear. Rabbi Herzog did not prepare the ground, and his own Religious Zionist party did not give him full support while the ultra–Orthodox and Orthodox forces were united. Besides, the local rabbinical establishment preferred weak, indecisive rabbis who would not interfere with their politics. Rabbi Herzog packed his bags and headed home where his congregation was waiting for him. Shortly after his return, the chief rabbi of Palestine, Rabbi Kook passed away.

|

Rabbi Kook was born September 8, 1865 in Daugovpils, Latvia. He was the oldest of eight children. His father, Rabbi Shlomo Zalman Ha–Cohen Kook, was a student of the famous “Volozhin yeshiva,” the “mother of the Lithuanian yeshivas,” whereas his maternal grandfather was an avid follower of the Kapust branch of the Hasidic movement, founded by the son of the great Rabbi of “Chabad,” known as the Lubavitcher Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneersohn of the city of Lubavitch.

Abraham Isaac Kook (Hebrew: אברהם יצחק הכהן קוק Abraham Yitshak ha–Kohen Kook) was the first Ashkenazi chief rabbi of British Mandatory Palestine and the founder of Yeshiva Mercaz Ha–Rav Kook (The Central Universal Yeshiva). He was a Jewish thinker, a halacha interpreter, a Cabbalist and a renowned Torah scholar. He was one of the most celebrated and influential rabbis of the 20th century. Rabbi Herzog announced his candidacy for the post of chief rabbi of Palestine while a local Rabbi Yaacov Moshe Harlap, rabbi of the “Shaarei Chessed” neighborhood in Jerusalem also announced his candidacy for the post. He had the inside track since he was in close contact with Rabbi Kook in Jerusalem. The ultra Orthodox and Orthodox forces joined ranks in support of Rabbi Harlap. He was a brilliant scholar but devoid of any knowledge or contact with the world outside of the yeshiva or the synagogue.[5] The local rabbis and politicians loved this candidate who would not interfere in their business.

The Jewish Agency representing the Jews of Palestine wanted to have a chief rabbi favorably disposed to the Zionist aspirations and a capable personality that could speak on behalf of all Jews. It was not interested in a local community rabbi. The Agency asked its executive office named the Vaad Leumi to officially invite Rabbi Herzog to participate in the election. He was a British subject, a religious Zionist, who served as the Chief Rabbi of Ireland from 1921–1936. Furthermore, Herzog was already known and liked by British Jewry and British authorities. He was expected to be an easy man to work with. He spoke English, was smart, affable, and, above all, was a well–learned Orthodox Jew, and considered a genius. The Mizrahi movement headed by the president of the movement, Rabbi Meir Bar–Ilan, actively supported the candidacy of Herzog.[6] Rabbi Hillaman from England who retired to Jerusalem actively lobbied for Rabbi Herzog in Palestine. The secular Zionist establishment in Palestine also pushed for Herzog's election.

Both sides were fighting hard to get the necessary votes for the election. Herzog was also acceptable to the Ashkenazi ”Lithuanian” rabbis because he was known as an outstanding Talmud scholar. Herzog's father–in–law Rabbi Hillman was one of the European Lithuanian rabbis, and quite respected. Both sides appealed to emotional slogans of Judaism. Finally, Rabbi Chaim Ozer Grudzinsky from Wilno publicly announced that he supported Rabbi Herzog for the position of Chief Rabbi in Mandatory Palestine. Rabbi Grudzinsky was a Talmudic scholar and a leader of European Orthodox Jewry. Next came the official endorsement of Rabbi Yossef Rozin of Dwinsk. These were influential leaders of the very religious Jewry throughout the world.[7] Still, the battle was not decisive, and votes shifted back and forth. The election committee consisted of 42 rabbis and 28 representatives of the various Jewish institutions in Palestine. The committee was ruled in accordance with the Ottoman regulations dealing with the selection of chief rabbis, chief cadis or chief bishops. Finally, the vote was held December 11, 1936 and Rabbi Herzog received 37 votes and Rabbi Harlap received 33 votes.

In his autobiographical book entitled “Living History,” Chaim Herzog wrote

“My father had won, thirty–seven votes to thirty–three, and we rushed to cable the news to my parents in Ireland. The election marked a major advance on the part of the Orthodox community in Palestine. It was a Statement that they were adapting to changing circumstances. … My father was a truth–seeker, and it was important to have such a man as a leader in the religious community. It is still important.”

Not a resounding victory, but enough of a majority for him to assume the position. Rabbi Herzog's tenure as Chief Rabbi would be different from that of his predecessor Rabbi Kook. Herzog was much more of an activist. What awaited Rabbi Herzog was nothing less than witnessing the near destruction of the Jewish people, and then the challenge of rebuilding those remnants saved from the ashes. His efforts would have a lasting impact, taking him to meet many of the world's leaders to plead for help in the rescue of Jewish children.

Rabbi Herzog was informed of his selection and traveled to Marseilles where he took a boat and sailed for Haifa, Palestine with his family. He proceeded to Jerusalem to assume his post. Everywhere crowds met the rabbi on his way to Jerusalem. The Mandatory authorities provided all the necessary provisions for the smooth installation of the Chief Rabbi of Palestine. The rabbi received a modest residence where there was hardly room to move about. The Rabbi immediately took matters in hand and began to establish a National Religious court that would deal with Jewish religious laws. The activities of the rabbinate also became public knowledge that helped to popularize the Rabbi's office. Letters of religious inquiries began to arrive from around the world and the Rabbi's office replied. The office became a center of religious activities. Rabbi Herzog used all the help he could get in his organization of the Rabbinate. His older son Chaim was there to help.

Jews lived in Lomza since the beginning of the 16 th century. In 1556 they were forced to leave the city when the residents were granted the “Privilege de non Tolerandis Judaeis” or the repeal of all Jewish rights. The city immediately implemented the document. Jews did not return to Lomza until after the Congress of Vienna in 1815. Once they were permitted to live in the city, the Jewish population began to grow. In 1808 it had 157 Jews, in 1825 there were already 737 Jews, and 2374 in 1852. The Jews took part in the Polish uprising against Russia in 1863. The Jewish population increased greatly with the building of the Augustow canal that opened the area to commerce. The city became an educational, and cultural center of north-eastern Masovia as well as one of the three main cities of Podlaskie Voivodeship (beside Białystok and Suwałki). The town is also the home of the Łomża brewery. In 1915 the Jewish population reached 11, 088 including a sizable number of Jewish refugees. They were also very active in the economic and financial development of the city. Jews actively participated in the municipal government. The Jewish population was basically poor, consisting basically of small store owners, stands and peddlers. The Jewish population consisted of “mitnagdim” -followers of strict Torah studying and “Hassidim,” followers of the Hassidic rabbis. The latter were in turn subdivided between the Hassidim of Gur and Alexander. The city had

|

|

| Chaim Herzog in the IDF (Israel Defence Forces) |

Chaim Herzog was active with the Federation of Zionist Youth during his teenage year, had immigrated to Palestine in 1935, attended a religious seminary and served in the Jewish paramilitary group the Haganah during the Arab revolt of 1936–39. He went on to earn a degree in law at the University College, London, and then qualified as a barrister at Lincoln's Inn. During WWII he joined the British Army, and joined the Armored Corps. And then worked in Intelligence. Engaged in the defeat of Nazi Germany, Chaim or Vivian Herzog identified Heinrich Himmler a leader of the S.S. among the German prisoners of war. During the formation of the Israel Army, Chaim was made an Intelligence officer because of his background. He rose to the rank of Brigadier General, and later was named Israel's 6th President in 1975.

In his first year in office, 1937, Rabbi Herzog witnessed the arrival of 60,000 Jewish immigrants to Palestine. Fearing conflict between Jews and Arabs, and aiming to stay on good terms with the Arab countries that were British trading partners, the British began to strangle Jewish immigration to the country. The Mandate Authority in Palestine began to dismantle the Balfour Declaration promise to help establish a Jewish home in Palestine. All kinds of restrictions and modifications were imposed on Jewish immigrants to Palestine. Officially Britain claimed that there were no changes, but it was obvious that the British government decided to side with the Arabs. To cover their actions the British arranged conferences between Jews and Arabs doomed to failure from the start. One of the reasons was that the Arabs believed the British were on their side. This emboldened the Arabs to impose impossible conditions in the negotiations: namely no Jewish immigration to Palestine. No Palestinian Jewish leader could accept such a proposition. While the change was taking place, the Jewish Agency was divided as to what action to follow with regards to Britain. Some, like Ben Gurion, head of the Jewish Agency Executive Committee, wanted to adopt a more militant attitude towards Britain, especially regarding immigration of Jews to Palestine, while others, like Dr. Chaim Then came along the Evian Conference in July 1938 in France called by Franklin D. Roosevelt to discuss the Jewish refugee crisis.[8] Britain consented to participate if Palestine was not mentioned at the conference. The United States accepted the limitation. The English delegation to the conference included Golda Meir, representing Palestine but she was not permitted to speak or ask questions regarding Palestine. The British muzzled her. Between 1933–1938, Palestine admitted 187,941 Jewish refugees quite an impressive figure of refugees. Yet Meir was not permitted to utter a word at the conference.

Golda Mabovitch, was born May 3, 1898 in Kiev, Russia, present day Ukraine, to Blume Neiditch and Moshe Mabovitch. Her father left for New York and then to Milwaukee, Wisconsin in search of a carpenter job. He found one at the railroad yard and managed to save money to bring the entire family to the United States. Golda attended the local school. She went on to graduate as valedictorian of her class. She continued at North Division High School and worked part–time. She left home and went to live with her married sister, Sheyna Korngold. The Korngolds held intellectual evenings at their home, where Golda was exposed to debates on Zionism, literature, women's suffrage, trade unionism, and more. In Denver, she met Morris Myerson, a sign painter, whom she later married on December 24, 1917. Golda Myerson was an active member of Young Poale Zion, which later became Habonim, the Labor Zionist youth movement. Golda continued her education and graduated from the teachers college – Milwaukee State Normal School (now University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee), in 1916. She began teaching in Milwaukee public schools in 1917 and also at a Yiddish–speaking Folks Schule in Milwaukee.

The Myersons came to Palestine and joined kibbutz Merhavia in the Jezreel Valley. The kibbutz chose her as its representative to the Histadrut, the General Federation of Labour in 1924. They had two children: their son Menachem (1924–2014) and their daughter Sarah (1926–2010). In 1928, Meir was elected secretary of Moetzet HaPoalot (Working Women's Council), which required her to spend two years (1932–34) as an emissary in the United States. The children went with her, but Morris stayed in Jerusalem. On her return from the United States she joined the Executive Committee of the Histadrut and moved up the ranks to become the head of its Political Department. In July 1938, Meir was the Jewish observer from Palestine at the Évian Conference, called by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Her political career continued to grow and she eventually became prime minister of the State of Israel.

Footnotes

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Children Train

Children Train

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 22 Jan 2018 by JH