[Page 83 - English]

Holocaust and Destruction

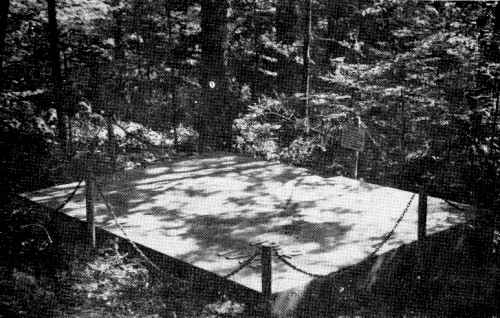

THE COMMUNAL GRAVE

OF BRZOZOW'S JEWS, MEN, WOMEN

AND CHILDREN, MAY GOD AVENGE

THEM, WHO HAD BEEN MASSACRED

BY THEIR DAMNED OPPRESSORS.

AUGUST 10, 1942

“…and set me down in the midst of the valley which was full of bones…;”

“those bones are the whole house of Israel…”

Ezekiel 37 (1, 11)

[Page 85 - English]

The Poland Document

A Protocol of the Events Witnessed

by Yisrael Dov Weitz from Bilitz, next to Katovitz

Yisrael Weitz was born in the town of Bobow in western Galitzia, and lived during the period of the war until his deportation in Jesienica. He was, together with all the youth of Brzozow. Yeshnitza and the surrounding villages, in the camps of Plashov and Prokocim. Having lived through much, he succeeded in the end in fleeing from the Nazi hell, and arrived in Israel in 1944 during the War. At this point in time, Poland, Lithuania, and the other conquered European countries had been emptied of Jews, except for Hungary, where the satanic murder plan to be promulgated on the Jewish population was still in its planning stages.

The events witnessed by Weitz were attested to at a time when the mass exterminations were still in the realm of rumors without official confirmation, and many in the free world, including Jews, were hard put to believe them.

His accounts include many details which were fresh in his memory at that time, and some of them awaken old memories in us when we try today to reconstruct all the events of that terrible period.

Weitz's description also relate to the Jews in the areas surrounding Brzozow, Yashnitza, and the adjacent villages, all of whose destinies were woven together with that of the Jews of Brzozow, and all of them were subject to the same fate.

The detailed listing of the name of the despicable murderers (which was shortened, by the way, in this paper) undoubtedly still cause revulsion even to today's readers, -- was compiled under the assumption that it would lead to their discovery and arrest.

It is now apparent that people at that time still sincerely and innocently believed that the German war criminals would receive their just punishment.

These accounts were published in the chronicles of the Rev. Dr. Gutman “Documents of Events witnessed by Jews during the Nazi Period” which was printed in Tel Aviv at the beginning of 1945 in German. These accounts have been directly translated from the German, with only minor omissions.

A.L.

Sworn Declaration

Documented in Tel Aviv during 21, 22 of June 1944

During the late night hours between the 3rd and 4th of August 1942, I was evicted from my place of abode (then) by the Gestapo, who was in the town of Yashinitza in the district of Krosno. I was 23 years of age. I left my dear parents, my father Yonatan Ze'ev Weitz, my mother Mirel (previously Galrenter-Gotvirt), daughter of the Rabbi of Zator. Both of them were in their 50's. Also my sister Nechama (26), her husband Shlomo Goldstein (27) (who later joined me in Prokocim before being sent as a cook to a S.S. concentration camp in Krakow, 77 Gregorska Str., and in April 43 was transferred to Yorozlimska camp), and my youngest, departed sister Mindel (17) whom I'll remember all the days of my life.

All the young men between the ages of 15 and 35, who were in sound physical condition, were supposedly to be sent to labor camps. The action began on the night between the 3rd and 4th of August '42. The concept “death camp” was as yet unknown to us, and as such we did not know that those remaining behind would also be evicted. On the contrary, we were told that if we presented ourselves for work, our families would be permitted to stay where they were, and we ourselves were supposedly to return home after six weeks. We were advised not to load

[Page 86 - English]

ourselves down with belongings, since we would be staying in Wermacht bungalows which would be well provided. Also those who did not present themselves, or hid, or fled, would be killed along with their families.

Therefore we presented ourselves, in accordance with the directive, at one o'clock that night in the street in front of the “Judenrat” in Yashnitza, and there we mustered. We were 162 males. We were taken by the “Judenrat” a distance of 16 kilometers from Brzozow, and we arrived at 4:30 in the morning, when we were put into the German “Shutzpolitzei” square. The youth of Brzozow already stood ready to march. Then we were handed over to the authority of the German Gendarmes of Brzozow. An hour later the Gestapo officers arrived by car from Krosno ad Yaslo. The Gestapo commander from Krosno was called Schmertzler: his two second-in-commands were Beker, and Ludwig von Dawire. Rashvitz was the notorious cunning commander from Yaslo, his two second-in-commands were Mattus and Romans. Romans' duty was the disposal of Jewish property. Accompanying them was a civilian clerk who was responsible for running the labour exchange of Yaslo. (Yashnitza was part of the Brzozow district, which belonged to the Krosno region, which in turn came under the auspices of Yaslo). The Gestapo officers repeated the check of the list of names. Everyone was examined separately to determine his ability to work, and the quality of his vision. Yashnitza was a small settlement with a high concentration of Jews, since six weeks previously, all the Jews in the area had been shifted to the settlement. They arrived there with no possessions.

There was no place to board them, and food was rationed to a minimum. Previously the Jews of the area supplied food to the town – this source was now completely blocked. The results were malnutrition and weakness. That was one of the reasons for the intensive examination by the Gestapo. The weak and those with any defects were returned home immediately, and similarly any tradesman who had worked in his profession for more than three years.

A special degree of cunning was behind this last mentioned decree. It was aimed at calming the remaining Jewish population, and preventing the slightest fear from arising as to the intentions with respect to them. If we could have guessed, even in the slightest degree, the danger confronting us, we would have not proceeded without resistance to our destinations. After the examinations, we numbered, together with the men from Brzozow, 306 men. Now they began to maltreat us for pleasure; under a rain of curses, we had to push 3 heavy loaded vehicles a distance of 300 meters. There was no purpose in this work other than to humble us, and break our spirits. Then came the command – jump to attention! Under the blows of the Gestapo, we were pushed and pressed, quickly and with no resistance, into the 3 vehicles. The suffering was impossible to describe. The Yudenrat from Brzozow had to supply each of us with a loaf of bread. Members of the Yudenrat threw the loaves into the vehicles (cars) and each man tried to catch them. The conditions were terribly cramped – this was an innovation of the Nazis. In order to catch a loaf, one man would press against another, push him, climb on him, etc. From the entrance came the order to cease supplying the loaves, the reason given being that “They don't want any more!”, when in actual fact we were lying, one on top of the other, trying to get a dry piece of bread, without any real chance of achieving that goal. The cars moved at great speed, which in our jumbled positions, made our condition catastrophic. Having come to the conclusion that they had nothing to lose, four youths from Brzozow used this hilly journey to make a bold escape. The Gestapo, following behind us in their cars was on an upgrade. As soon as those attempting to flee were out of the line of sight (of the Gestapo), they jumped into the ditch and hid there. Later on I heard that these youths returned to Brzozow, hid there until the evictions began, and then were taken to an extermination camp along with the other Jews. We were taken to a train station at a holiday resort, Ivonitz. On side rails, were waiting two closed cars used for transporting cattle, with small hatches at the top. We still numbered 302 men. No one took any notice of the 4 missing passengers. 151 men to each wagon. The summer was at its peak. One lies on top of the other. No water. Terrible thirst tortures us. I'm one of the few who speaks German. I'm chosen as a spokesman.

My job was to approach the Gestapo commander Rashvitz and request that he provide us with water for the journey, and not close the doors. We would choose 10 men, who would maintain control, and especially, would ensure that no one left the car. In any case no one tried to escape, the area was com-

[Page 87 - English]

pletely populated by non-Jews, and there was no possibility of escaping.

I went to Rashvitz and presented him with our requests. The Nazi's answer was “I believe that no one intends to escape, but someone might fall, G-d forbid, and who would stand trial for that?” As for water, he turned to one of the policemen and told him to deal with it. He escorted me to a Goy who lived close by the station, and he lent me two buckets. I drew water from the well, and gave one bucket to each car. They finished it in an instant. Escorted by a policeman with a gun, I go again and again, until all had drunk. After returning the bucket, I asked Rashvitz for permission to buy the buckets so that we could have water for the journey.

This request he refused outright! Trade between the Jews and the Polish farmers belonged to the past! “Stop prattling Jew! Forward. Get in! Los! Los!” With his own hands he closed the door to the car and sealed it.

We stood in the station for two hours until they connected the 2 cars to a goods train. The Gestapo left and police took on the job of guarding us. During the first hours of this August morning, we had not yet begun to feel the terrible heat in our prison. Towards the afternoon however, our position began to become intolerable. At the stations we passed through, we shouted our please for water, but to no avail. In the car, two groups formed. One group demands to open the door by force, and jump out. The second group warns of certain death. Their opinion is to wait, and see what awaits us at the camp. There would always remain time for us to take the final road. This group, to which I also belonged, represented the majority, and warned: “Don't dissipate our force!” We did not know what would happen to our comrades in the second car.

In the afternoon the situation worsens. Many faint, but there is no help for them, and no possibility of doing what is needed. The air is foul, and the number of those fainting climbs all the time. Like salted fish we are compressed, one lying on top of the next. We try to raise those who have fainted up to the small windows at the top, so that they can breathe some air. Next to me sits a youth, Moshe Feingold (the reference is to his brother Meir) secretary of the Zionistic youth of Brzozow. He faints, and I'm not able to succor him. Since we have all tripped because of the oppressive heat, I take a piece of clothing and hold it out of the small window in the wind, so that it will cool down, and with it I try to revive him, until he recovers and says “Why do you help me, and not lay me down to die?”. In these dreadful conditions we travel during the entire day, until towards 8 that evening we arrived at Krakow – Plashov. There the order was given by the police to prepare to leave the train. We dressed, but still had to suffer the cramped conditions, and the foul air for another three hours, and these became even more terrible because the train was standing Their aim was to humble us and prevent the people in the area from seeing us. The police are reinforced by SS men, we are ordered to remove the dead and the half dead, and to lay them on the quivering tracks next to the car. We found that no one had died, but 15 men were in deep coma, without movement, and in a very serious condition. 30 men from among us had to step forward, and each pair had to carry one unconscious man to the camp. It's already midnight. They're taking us to Prokocim, a village near Plashov. They fire constantly, to frighten us and to ensure that no one escapes. They bring us to the camp sheds, and hand us over to the guards. They force us into a half-completed shed, an open roof, and it was obvious that the previous day heavy rain had fallen. The floor was covered with puddles of water. After our awful journey, we found ourselves on ground that was soaking wet. We beg for a mouthful of water, but it's denied. “Jews are forbidden to cause a commotion in the middle of the night.” They were never short of an answer. At six in the morning, we are awoken from a leaden sleep. The company “Klug, Hoch and Tiefbau”, whose headquarters is in Regensburg (Germany), was operating in the area, primarily building roads and laying railway lines. The foremen of this company come to fetch us for work. On an empty stomach, we walk to Bzezanova, a distance of about 14 km., escorted by an armed guard party, we begin to work. At the lunch break, which lasts half an hour, we are given hot vegetable soup, and then we carry on working until 7 at night, after which we march, escorted by the armed guard back to the sheds at the camp. On the date 6/8/42, the foremen of two more distant “Hoch and Tiefbau” companies arrived to choose laborers for themselves. The specific names of these branches were “Stuag” and “Ambi Schroeder”. In the Klug Company there are 160 men, the rest being divided between the other two firms. In the Stuag company, we meet with some of the Jews from Ri-

[Page 88 - English]

manov, who have been transported there some three days before us. I was assigned to the Klug firm. Here the application of discipline was the most intense, because the camp commander, a Saxon, was a genuine sadist.

The working day starts at three in the morning with the shout to arise! After five minutes, to be at assembly! We get hot drinks that have been prepared by our friends who have gotten up an hour earlier. By 3:30, everything must be read for departure. The camp guards escort us to the place of work riding on bicycles.

We arrive there at 5:15. Work continues until 7 at night, except for the half hour lunch break when we get the soup to eat. After a day of back-breaking work, we have to march back, tired and hungry, the full 14 kms. We arrive back at the camp at 9:15. Each prisoner receives 200 grams of bread and 50 grams of jam. Half of this we eat for supper, eating from the boards on which we sleep and the other half we keep for breakfast.

After we return, it is forbidden to leave the shed and forbidden to go to the toilets. On August 8, I saw two of our group lying, shot, in front of the shed…they had gone outside during the night to attend to their bodily functions. The guards tell us “These two planned to escape, so we shot them. Anyone who wants to leave the shed at night must do so completely naked”. This we are only told now. Two of us became victims before the witty lawmakers told us their clever rules.

Those who had passed out (on the journey), had recovered in the meantime, and were considered fit enough to join the work parties. Only four were still in a serious condition, lying without treatment or medical help in the shed. We are informed that those who suffer a prolonged illness will be killed. At this, I go to the camp commander, knock on his door, and subserviently go into his room. He immediately grabs me, gives me a blow with his fist, throws me out and says “If a Jew wants to talk to me, then only from outside, a distance of three paces from my window”. I do as he orders, and stand and beg him to allow me and two helpers, to take the four sick men to the hospital in the Jewish ghetto in Krakow. (The ghetto in Krakow still existed. It was completely destroyed in March of 1943). He allows me this, on condition that we bear the costs of the necessary transportation. He assigns a guard who escorts me to a farmer who lives nearby. There I hire a carriage. The farmer travels with me to the camp. I receive a pass from the camp commander, with the following wording: “The Jews Yisrael Weitz, Belzer Neta and Nadelshtechter David have permission to travel to Krakow, to the Jewish ghetto, with the patients Shtrasfeld Moshe, 24, Boksbohm Haim, 29, Zultig Mordechai, 23, Lipiner Salka, 27,… duration of this pass is from 3-9.8.42.” I am allowed to carry out the assignment without being escorted by a guard. We load up the sick men, travel to Krakow and deliver them to the hospital. We later heard that a gloomy fate overtook them. Boksbohm Haim lost his mind, Zultig Mordechai died three days later, Shtrasfeld Moshe and Lipiner Salka recovered, were returned to the camp, and later, exterminated.

The three of us remained illegally in the ghetto, where we got in touch with Meir Roth, who obtained for us three train passes. We were given permission to travel for three days to Yashnitza to buy hair for the brush industry (for the Wehrmacht). We received a little money from relatives who were still living at that time in the ghetto in Krakow. My two friends raised the rest of the money by selling their raincoats. On 11/8/42, we left the ghetto, the passes in our possession allowing us to exit through the gate of the ghetto which was guarded by Polish policemen.

From there we went to the railway station where we had to identify ourselves a number of times for SS guards, and also when purchasing our tickets. Everything went successfully. We board the train and leave on our journey. Before Bochnia station, about 50 km. from Krakow, a Polish farmer's wife from Yashnitza recognizes Nadelshtecher and asks him where he's bound for. His answer was home to Yashnitza. To this, she replied that his journey was pointless, because that night all the Jews had been removed from Yashnitza, and any Jews found there now would b e put to death. We alight from the train in Bochnia with the intention of phoning from there to confirm the news but were unsuccessful. Although we did make contact, the clerk in the post office told us “We do not have permission to speak about events in Yashnitza, and especially not to Jews”. The position became clear. We stayed over two days in Bochnia. Here there is still a Jewish population. Our position was as follows: We couldn't return to Yashnitza… it was impossible to return to the ghetto… the position is the same in Bochnia, because we do not have permits to stay there. We realized that all

[Page 89 - English]

was lost, and resigned ourselves to die. David Nadelshtecher, convinced that his family, in other words his mother, his wife, his daughter of 3 and twins of 9 months, were hiding with Christians, decided to continue the journey, using his pass, to the “Ivonitz zdroj” station. I gave him the money I had left and he went on his way. My friend Belzer and I hid for a few days in Bochnia, where we were supposedly to get information from our friend David N. Four days later, we received a detailed letter, from a Christian address, informing us that he was staying with a farmer, and his wife and children were with him.

When his wife was told about the approaching genocide, she took the children, and, courting greater danger, fled in the middle of the night to the farmer from Wald Yashnitza. His mother and her husband were not capable of making the difficult journey under the awful conditions then prevailing, and stayed behind. He made his way to that farmer directly from the train station. He did not advise us to join him, because of the danger, and also since the farmer was unable to take any more fugitives. He then went on in detail to tell us about the genocide which had occurred on the night between the 10th and 11th of August (the 28th of Av) and which continued during the entire day that followed.

That night there suddenly appeared the Gestapo from Krosno and Yaslo, with the notorious Rashvitz accompanied by large numbers of SS men, and police. They brought with them numerous large goods vehicles. The town was surrounded by the murderers. The officers assembled at the “Judenrat” building, and ordered all the town's Jewish inhabitants to present themselves at the market square. No questions were permitted… only obedience was required. The square filled up within the hour, with everyone from infants to old people.

Everyone was checked against the list of names. So that simultaneously they might mislead the victims and conceal their devilish plans, and also to ease their way for the confiscation of property afterwards, the devil announced from the largeness of his heart as follows: Each family could appoint one representative, who would have one hour to pack 10 kg. of belongings from their houses. This was to include all food and clothing, etc. When this legal fiction was carried out, the dawn began to break, the order was given by the Gestapo for everyone to kneel down on their belongings with their hands behind their backs, until all the houses of the Jews, and also those of their neighbors (non-Jews), had been checked for possible runaways. Anyone who lifted his head would be shot on the spot. This process continued until the afternoon, during which time there were several victims.

In the afternoon, the selection process began according to what were obviously well planned lines:

- First line: mothers with infants in their arms, and children not yet able to walk.

- Second line: children up to age 14.

- Third line: old people.

- Fourth line: middle aged women (this group included some young tradesmen who'd returned from Brzozow on August 4th).

The action began. The mothers, infants and young children marched in the first row. They led to the cemetery. While the Jews had been kneeling in the market square, a group of Polish slave laborers from Krosno had been brought specially by car, and they had dug a large mass grave measuring 8 by 15 meters and two meters deep. The SS men killed the infants with their own hands by crushing their heads on the tree trunks, and threw them into the pit in full sight of their mothers. The second row arrived: the children up to age 14, and with them, several mothers who had refused to be separated from them. They were thrown into the pit and machine gunned. As for the mothers of the infants, the Nazi animals had prepared a special game for them. First they had to strip naked, and then they were thrown onto the carnage in the pit, where they were machine gunned. The suffering had reached its peak.

The old people were ordered to surround the pit, with their faces towards it. Then they were shot in the knees, and fell into the grave. All was covered with earth.

Remarks:

There are no words in the human language to describe the horrible tragedy. If later I would have not witnessed with my own eyes the same outrageous events which happened in November 1942 in Bochnia, I would never believe, that something like that could happen. At the same time many others who did not live through this experience, cannot believe till now, that such an event occurred.

The men and women remaining in the square wee loaded onto the goods vehicles and taken to the railway station at Krosno, a distance of 20 km. There

[Page 90 - English]

they were shoved and pushed into railway cars, and left thee for two full days without food or water until the action in Krosno was finished. There were similar actions in Rimanov, Dukla and Kortzin on 13.8.42.

On the same day, August 10, 1942, the action was carried out in the same manner as in Brzozow. In the midday hours you could see trucks loaded with Jews, middle-aged men and women, riding through Jasienica. At that time the Jasienica Jews did not yet know where they were taking the unfortunate ones, and what was going to happen to the mothers and children or the old people left behind.

After the actions were carried out, the Jews that remained at the railway station in Krosno were led away to the Belzec extermination camp. In Jasienica, David Yoshua Zicherman, the head of the “Judenrat”, along with his wife and five year old daughter, were given special “treatment” (His twenty-three year old son Moshe was sent to the extermination camp.) The bandits Rashvitz Mateus and Romans considered themselves as “good friends” of the Zicherman family, they used to eat and drink there. During the liquidation, Rashvitz left Zicherman and his family in their house. After Rashvitz, along with the other murders, finished their killings, he went to Zicherman's house, led the family into the courtyard, ordered them to undress and killed them all.

It was now clear to us that we could no longer stay in Bochnia. We decided to go to one of the camps near Krakow. Our relatives who were hiding us provided us with work clothes. We stuck the white ribbon with the Star of David in our pockets in order to use it when we entered the camp.

We travelled by train to Krakow-Prokocim and hid not far from the workplace of the firm, Abi Schreder from Bierzanow. At dusk, when the work ended the forced workers stood in lines to go back to the camp; we put our armbands back on and joined the group marching together with them without attracting the attention of the guards. The camp leader did not know us because we used to work at another firm. We told our comrades what happened to us and all the information we received from David Nadelstecher. One can imagine the impression that was made on them, but only the thought of revenge gave them strength to live in such degrading conditions. To gain acceptance into the camp we went to the camp leader and informed him that we belonged to the young tradesmen who had been sent back from Brzozow to Jasienica and, after a cursing out, the head Gestapo chief “Obersturmfuhrer” Rashvitz had ordered us to go to Bierzanow to the firm “Abi Schreder” where our comrades were. As proof I took out my identification as a textile technician and weaver. He, actually uplifted by the honor with which the big commander treated him, said to me, “Actually I do not need any more Jews to work, but we will create something. You remain with me and the others go over to the firm of “Schwag”.

The workers who worked in Bierzanow were given quarters in the camp Prokocim and the Prokocim workers were taken to Bierzanow. In order to torture the people they made them march about 14 kilometers twice a day. The same thing happened to those who worked in Plaszow. Many of the people brought over perished. Some from illness (typhoid) and others from the Ukrainian guards under the leadership of SS “Obersturmfuhrer” Hans Miller, who was stationed in the Plaszover camp and whose direction our camp was under, would appear in the camp very often and carry out a “control”. There were no controls without victims. Because of malnutrition and general weakness many would remain lying on their bunker boards and not go out to work. Miller made an ordinance that whoever was missing three days from work would be shot.

In each camp there was indeed one Jewish doctor and two medical assistants, but they were not able to help because basically there was no medication. There was no possibility of washing in the camp and there was o faucet with drinking water. Once a week, on Sunday afternoons, they let us into the ghetto where we were able to wash ourselves and they disinfected us. After that we received an official confirmation that we were clean. I came to the conclusion that I could o longer stay in the camp and tarried to escape a second time.

Sunday, after washing myself I did not return to the camp, but remained in the ghetto. During the twelve days that I was there all the Jewish communities in the surrounding towns were liquidated and all became “Juden-rein” (clean from Jews) according to the Nazi terminology.

Meanwhile the ghettos shrunk. People remained only in Krakow, Bochnia, Tarnow, Rzeszow and Przemysl.

In the Bochnia ghetto a liquidation action took place on the 28th of August and a small number of capable workers were left over. Those remaining re-

[Page 91 - English]

ceived special confirmation from the Gestapo that they were still useful. The confirmations carried the seal of the commander of the security police from the district of Krakow.

As I mentioned before, I did not return to the camp. I soon realized that I could not go around without documents. Through the messengers of the camp who were sent to the ghetto to take care of different matters, I was able to contact my friends. One of them was Isaac Brosman from Jasienica who got the necessary confirmation for me. He went to the camp leader with the proposal that he should go to Bochnia to bring clothes and underwear for himself and the others in order to make the conditions of the camp more bearable and sanitary. The camp leader agreed and filled out the permission slip by himself which was written according to Grossman's request under the name of Israel Weitz. On September 4th I arrived in Bochnia. There I went to the “Judenrat” with a request to join any working group so that I could remain there. They rejected my request because they had to first legalize the Jews who had been hidden during last action. I was there for several days illegally without any prospects. I finally managed to get myself some trade work. The document that I was waiting for finally came with the stamp of approval from the Gestapo. The same day I was sent with 15 other men to the firm, Walter. The workplace was located 12 kilometers from an ammunition warehouse. Two hundred and eighty Jews were working there, all of them packing the ammunition into boxes and loading them into wagons. Meanwhile we were occupied by erecting a concrete fence around a huge area.

One day the Chief of Gestapo, Shumberg, arrived and requested a list of trade workers who were designated to work by hi8m in Z.F.H, Central Employment for Trade Expedition. I was assigned to the group as a weaver. They took me to Bochnia and until the built the weaving factory, I worked erecting a fence around the ghetto. A week later the horrible murder action started in Bochnia. The ghetto was surrounded at night with the SS security police, military police, and special servants (Sonder-Dienst). Murder groups were not missing. Nobody was let out to work. The main murderers arrived. Chief of the Krakow district, Dr. Scherr, Police Commander “Obersturmbahnfuhrer, Dr. Scheiner, Vice Commander Groskopf and others. The already mentioned Schumberg from Bochnia joined them and the local police chief Lipman. The first to be arrested was the “Judenrat”.

Those who worked in the trades Expedition positions and in the workshops fixing train cars were sent out to their jobs. At the time the police guards were sent out the murderers penetrated into the ghetto. The slaughter that we already know about from Jasienica and other towns repeated itself. Complete annihilation from the youngest to the oldest. Seventy six prisoners from Wiasniow prison, (their crime was buying bread without a card or forgetting to put on the armband), were shot in the middle of the streets. The sick that were found in the hospital were killed in their beds and then they shot all the nurses. The principal murderers wee the German police of Bochnia.

When we arrived at the building of the trades Expedition we heard echoes of the shooting in the ghetto. The bloody action lasted from noon until the next day. Then the German police came and led us over to the ghetto to bury the murdered. We found broken and robbed houses filled with blood and human limbs. The next day they took me with a group of workers over to the hospital to put it back in order – to take out the dead, wipe off the walls, wash the doors and clean the beds that were covered with blood. The remaining Jews were led over to a camp that was called “Official” (a forced work camp for Jews District Krakow, in Section Bochnia).

After the November action all remaining Jews received a white piece of linen 7 cm. x 7 cm. with the letter “R” which meant “ammunition production”, along with a running number with a stamp from the Security Police in Krakow. This one had to be worn on the breast. These same procedures were introduced in the camps of Krakow- Jerozolimska, Tarnow, Rzeszow and Przemysl.

In the camps near Krakow our comrades suffered from terrible hunger. We managed to get permission to take flour from the giant warehouse in which large amounts had accumulated that had belonged to the bakeries of the murdered Jews. We managed to send several hundred loaves of bread a week to the camp of Plaszow where our townspeople were quartered. We were also successful in sending a little clothing and medication. After a short while our shipments were prohibited; the mail stopped coming to us and we became completely isolated from the world.

Shlomo Greiber, whose wife and children were murdered during the action, was successful in running

[Page 92 - English]

away and escaping. He is now in a safe place, I cannot give any details about it. (It was witnessed in 1944. – The editor).

The final liquidation of the 25, 000 Jews in Krakow ghetto took place in March 1943, and was carried out by the same bastard murderers. From the approximately 7, 000 workers, capable men and women were led over to the camp in Jerozolimska Street. The gravestones from the Podgorze Cemetery that were found there were taken away and in their place were erected barracks. The SS Storm Leader GET was appointed as commander of the camp. I knew this outcast from before. He was carved in my memory as a tyrant of the worst sort. He was the embodiment of the Nazi type – a pretty wrapping under which is concealed a dirty sadistic bastard. Daily, with his own hands, he murdered Jewish workers. This gave him the greatest pleasure. In order to bury the victims quickly, he put together an orchestra of Jews who were forced to play after every murderous act.

After the liquidation of the Krakower ghetto, my already dispersed family shrunk and the only survivors were my father's sister, Nechama, and her three daughters. Her husband, Isaac, was murdered a month before and she and her daughters went over to the camp in Jerozolimska.

Her oldest daughter, Esther Weitz and her friend Saltz, both 19 years old, could not endure the terrible conditions in the camp and made an attempt to escape. They were caught and immediately sentenced to hang. All workers were ordered to gather around the gallows; the mothers and two sisters were forced to stand nearby. Get himself carried out the murder. With a pride which proclaimed wonder, the two girls went to the gallows. Get put the rope around her neck. When Esther Weitz was hung by the Ukrainian, the pretty and developed girl was successful in freeing herself from the rope and she fell to the ground. The suffering of the mother and sisters who were forced to watch all this is indescribable. The German hero was enraged. He began to step on her with his feet and beat her with a whip until her whole body was black. She did not let out a groan. After that, with his accursed hand, he took out a revolver and shot her. Her friend Saltz was hung and the digger pushed both their bodies into a ditch near the barracks. The suffering of the survivors went on. The orchestra got an order to play.

All this I heard from a reliable witness, Eliezer Frenkel who ran away and came to Bochnia. He also brought us news of the 302 people from Brzozow and Jasienica, who were brought in the beginning of August, 1942. By April, 1943, 96 had died of disease (typhoid) ad 67 were shot. In April, the inmates from the camps of Plaszow, Prokocim, Bierzanow and the workers of the ammunition camp were brought to the barracks of Jerozolimska. All together there were 13,000 Jews. In the final report that came to Budapest in October of 1943, only 6,000 remained alive.

On the eve of Passover, April 7, 1944, all the valuables were taken away from the Jews; they were permitted to keep one suit, two shirts, two pairs of socks and a pair of shoes. On the outer garment a large yellow square was drawn that was permanent, in order to make it impossible to escape. Get was nominated as the chief commander of the five camps in the District of Jerozolimska, Tarnow, Rzeszow, Bochnia and Przemysl. His impudence and blood thirstiness had no limit. Because of his ability and skill in torturing the Jews he advanced in rank.

We were informed that a total liquidation was being planned. Three comrades, beside me, decided to run away. The three were the brothers, David and Wolf Hochberger from Bukowa and Leib Grosman from Krakow. According to the plan, we were to leave by truck from the firm “Ost Energie” and travel to the Slovakian border. Leib Grosman financed the escape. We paid 10,000 zlotys to the driver. We provided ourselves with documents in which, according to the request of the firm “Ost Energie” we were being sent to a sawmill in Polish “tartak”, a village in Sniatnice Grabower region, near the Polish Slovakian border. From there we were to bring telephone poles.

After making the proper preparation we ran away on August 21, 1943, at noontime. With the documents that carried the emblem of the firm and with the distinct letter “R” we went through the control. A Rutaner from Sniatnice was travelling along with us and for 2,000 zlotys per person, he was to take us over the Slovakian border.

On the way, 90 kilometers from the border, the car broke down. We ran quickly to the forest to hide. The driver of the car called several German workers to help him fix the car. Since it took a long time we gave up on the car. Meanwhile in the forest, several Polish youths discovered us and we were afraid that they would betray us as partisans. We changed our hiding place and waited until nightfall.

[Page 93 - English]

We approached the Slovakian border at the Eastern Beskiden Mountains. During the night we travelled forward and in the day we hid in caves. Our escape lasted for three days. On the night between August 23rd and 24th, we approached the border at Snitnice-Izbi. Here we were discovered by a German watch post with reflectors. We fell onto the moist grass in horrible fear. Four soldiers with loaded guns passed by 15 meters from us, but did not find us. When they got further away we went quickly through the border. The Rutener official that led us, gave us over to his partner on the other side who managed that same night to speedily cover over 30 kilometers to Bardiawa-Bartfeld. We stayed here for three days. Previously 30,000 Jews had lived there and now there were only 30 families. I stayed in the home of a man named Pinchas Landerer, who was the only survivor of his entire family. Our reception by the Jews in Bartfeld and everywhere in Slovakia was exceptionally warm and gracious. The hundreds of escapees from Poland who came after us were also treated to such hospitality. After three days, the Jews from Preszow sent a taxi with a gentile chauffer to bring us in. The reception in Preszow was very touching. They provided us with warm clothing and on the same night, for a good price, three Slovakians led us over to Kashov, Hungary. On the Hungarian side near the bridge, the border guards shot at us and came after us with dogs. We gave ourselves up to them. We begged them to free us and since they supposed that we were Christians, they let us go. We entered the town and after three days we travelled by train deeper into Hungary. My three comrades received a confirmation that they were Christians, however, my name, Stefan Rudnik, and the additional information given by me, was not convincing or sufficient. The detectives found out that I was a Jew and wanted to arrest me. I tried to run away, but they caught me immediately. Locked in chains, they lead me to a concentration point that was located in a schoolyard. After the investigation search they confirmed I was a Jews. I was taken to the concentration camp Magdalena. After ten days, I managed to escape. While wandering around Hungary I received help from the Bobover Rabbi Shlomo Halberstam, who managed to escape with part of his family to Budapest. Rabbi Shlomo was the son of the famous Bobover Rabbi Reb. Ben Zion Halberstam, who the Gestapo, with Ukrainian, aid led away from Lemberg (Lwow) in the year 1941, along with his son Moshe Aron and three sons-in-law, Yechezkel Halberstam, Moshe Stempel and Szlomo Rubin. I spent my youth in the home of Rabbi Ben Zion Rubin and studied in his Yeshiva “Etz Chaim” in Bobow.

After my escape from camp Magdalena, I spent several months in different Jewish homes. I tried to change my appearance as much as possible and grew a mustache and wore glasses. I tried every means to be legalized in Hungary. I went to the foreign control office, wearing winter clothes and declared that I had just arrived from Poland that I was a Christian and my name was Mieciciel Witold. My identity received official confirmation and I was assigned an apartment in Groswardein. There I moved on March 15, 1944.

The German's march into Hungary brought all kinds of well-known misfortunes. Jews had to wear yellow patches and all their businesses, possessions and properties were confiscated. It came to my attention that the Hungarian secret police were searching for me as a Polish Jew, in order to give me over to the Germans. I was able to get in touch with Mordechai Spitzer who had prepared a plan to escape to Romania.

On the seventh day of Passover, April 14, 1944, we escaped: Mordechai Spitzer, two daughters of the Bobover Rabbi Gitel and Rosa and myself. With the help of a Christian guide we got through the border and after five days we arrived in the town of Arad in Romania.

We made an agreement with the guide to bring more Jews from Grosswardeen. Several days later he came with eight more people. Nechamah Stempel and her two children, Ashkenazi and his wife, Eliezer Rubin, Szlomoh Kenigsberg and Tanenbaum.

Mordechai Spitzer continued his rescue mission and with the help of several Christian guides he managed, for a high price, to save about 70 more people.

I managed to obtain a certificate to Eretz Israel and my wandering from place to place and the sufferings came to an end. Ashkenazi, his wife and I arrived in Constantsa and on the ship “Maritza” we arrived in Turkey. From there, by train we arrived on the 25th of May in Haifa.

[Page 94 - English]

Six Weeks in a German Prisoner-Of-War Camp in 1939

by Chaim Bank

I would like to describe my six weeks of captivity as a prisoner-of-war with the Polish armed forces and particularly my experience as a Jew. Before beginning to write about these experiences I must turn to the events in Poland before the Second World War (1939-1945), the period before my mobilization in the army.

Soon after the death of the Polish Marshal Josef Pilsudski, the leaders of the Polish government started to endear themselves to the murder-gang of Hitler's Germany. Their headquarters were located in the capital city of Berlin, where they governed from the year 1933, and the time in which Adolf Hitler came to power.

The Polish population acted with strong envious feelings towards the leaders of Hitler's regime with the “Nuremberg Acts” against the Jews. The Polish authorities intended to follow in an exemplary manner the footsteps of Hitler. This was the beginning of a tremendous wave of mutilation and “Bacchanalia” (orgy) against the Jewish nation with the racial formula typical of Hitler.

After the German armed forces marched into Austria and with the accompanying occupation of Czechoslovakia, Hitler changed his attitude and tune concerning Poland and stepped forward demanding the immediate return of the “Free City of Danzig” situated in the passage of the Baltic Sea, as well as some western and southern regions of Poland assigned to it at the “Versailles Treaty” at the end of World War I.

Poland was not ready to return these territories to Germany, particularly since Poland held several political treaties with the French and English governments and counted on their help and support in case of a German assault. At the last minute Hitler reached the well-known agreement with Josef Stalin, the leading figure in the Soviet Union, and this action was a signal to invade Poland.

This particular week, on a Sunday, I had come to Brzozow (I was living at the time in Przemysl) to consult with my mother and my brother Meyer about the future of our store and how to handle things in case of the outbreak of war. That same day I received the call to the armed services and immediately requested the town of Brzozow to provide me with a means of transportation, which meant a horse and carriage. Thus mobilized and accompanied by three other Polish inductees, we arrived in the town of Sanok, the “Second Podhale” (the Tatra district) Regiment”. We drove to the “Polish Soldier” building in which the military commission was on duty to receive mobilized persons. There we were given an exam to check our physical and mental condition. When the military physician asked me if I was in good health, my reply was, “To beat the Germans I am as strong as a horse.” I was naïve to believe in Poland's power of resistance, as well as in the illusion about prompt assistance from the French and English governments.

It was 2 o'clock in the morning when we received military uniforms and weapons, with the exception of ammunition, suitable for the infantry division. A place to sleep had been assigned.

The following day, Monday morning, after our first military breakfast and dressed in uniform we assembled in the large hall of the Soldier's Home: The head of the division, General Boruta Spiechowicz delivered a short speech with the following conclusion, “the diplomats have stopped talking, now the cannons will begin talking…”.

Shortly afterwards I was called out to make the necessary swearing in for all Jewish soldiers. I was the only Jewish under-officer among the whole group. There were also two Jewish soldiers. The oath-taking was performed by the municipal Rabbi of Sanok, Rabbi Tobias Horowitz.

The following Tuesday night we were loaded into a cargo train without knowing in which direction we were travelling. After leaving the city of Sanok, we quickly reoriented ourselves. We were travelling towards the southwest of Poland. We arrived in Przemysl around seven o'clock in the morning. I asked Captain Kantor for permission to go to the railway station to phone my wife as we had no chance to even say good-bye to one another. My request was granted since departure from the station was delaying

[Page 95 - English]

by a half an hour. Our farewell was expressed in a very dramatic way.

As our travelling continued we passed cities and villages well-know to me, i.e., Przeworsk, Lancut, Rzeszow, Debica, Tarnow, Brzesko, Bochnia, Krakow, until we reached Zator, a place not far from Oswiecim (Auschwitz). Here we began unloading. Around four o'clock in the morning we heard the noise of German airplanes at a great distance. Some of the young officers tried to convince us that they were Polish planes. Since I was an observer for the company, I had in my possession field glasses and also knowledge of the military signs of each country in Europe; this gave me t he chance to rightly perceive that German planes were coming.

In a moment I started shouting “take cover” in Polish “kryj sie” and immediately the bombs began to fall. Then came the shooting of machine guns. The damage was not great, only a few lightly wounded soldiers. After the enemy planes were gone we were assigned ammunition and defense arrangements were made against future attack. All of that with three heavy machine guns, all that we possessed.

Events happened very fast. A few minutes after our “defense arrangements” an order came to remove everything and march in the direction of Oswiecim, which later became known as the main extermination camp of Jews from Europe. On our way we came across Polish military detachments and special artillery units which had withdrawn from the front lines under the heavy fire of German tanks and airplanes. The artillery unit was forced to leave behind the cannons, not having been able to hold out under the strong pressure of the German army. We also received a direct order from the Staff-General Mond, chief commander of the Silesia front. Rumors were circulating that General Mond had been captured by the Germans.

After the liberation I found out that in spite of being Jewish (he converted) the Germans kept the General alive. He died long after the war, of natural causes.

Our regiment was divided, one group was directed to back-track and seize the defense post on the road to Kalwaria-Wadowice; the second group to which my company belonged marched on the road to Krakow. As we approached Wieliczka the town was suffering heavy bombardment, therefore we were compelled to march in the direction of the river Dunajec and hurry to the other side. After a long, exhausting march we came to Radomysl in the evening. Here the group of soldiers who had backtracked were showing their “heroism” by breaking into Jewish stores and robbing the merchandise. I was powerless to take effective measure against that kind of behavior, because the officers had run away and the few remaining young reserve officers were afraid to oppose the wrong doing. I took stock of their “robbery” with the decision to break into a gentile store. Together with several soldiers we broke into a meat and “kielbasa” store and started to take all kinds of meat products. The owner started crossing his chest and saying that he was a religious Catholic man and not a Jew, but his complaints and grievances fell on deaf ears because the soldiers were generally hungry. This was a kind of revenge on my part.

We could not stay long in Radomysl because the Germans were very close by and we were forced to leave that town before nightfall. The German armed forces did not fight at night, turning the artillery fire away from town. By the reflection of the burning objects we were able to continue our march until we reached a village near the town of Kolbuszowa. There, for the last time, we tasted the German assault, which resulted in our falling into the category of prisoners-of-war.

Already a prisoner, while marching across the town of Kolbuszowa, I came across the scene of a Jewish Hassidic boy sitting on a chair in front of a house. I was astonished to see that under the existing circumstances a Jewish boy would have the courage to sit in front of the house. But my companion-in-arms (now prisoners-of-war) marching with us called to my attention that the seated boy was dead. Apparently a handicapped German officer, who was without his left hand, killed the boy as well as other persons he had met on the road. That same officer took hostage several prominent Jews as well as the head of the assembly of elders from Kolbuszowa, and on guard marched together with us to the city of Rzeszow. There we were brought to a school courtyard and kept for twenty-four hours.

Twice we received nourishment in the form of a bowl of soup from the German military kitchen. The Catholic nuns brought kettles of food for the Polish prisoners. The Jewish hostages from Kolbuszowa refused to eat non-kosher food and literally starved. I owned a few “zloty” (Polish currency) and asked the nuns if they could possibly buy me some chocolate in town. They fulfilled my request

[Page 96 - English]

and that chocolate was the only food the Jewish hostages would eat. The nuns let me know of the horrible misfortune befallen the Jews of Rzeszow caused by the German army right after the beginning of the invasion.

The next day we were loaded into cargo trucks and headed in the direction of Debica stopping in the town of Tarnow. We remained for a few minutes on Walowa Street near the City hotel, whose owner was a Jewish man named Weiss. I asked a person standing nearby to give my regards to an uncle, a resident of Tarnow. My request came to the attention of a Landsman from Brzozow, Asher Adler who was accidently there. He was able to throw a few apples up to me in the automobile. To speak was impossible for after several minutes the automobile departed with us. In a few minutes we came to the front of a building in which a gymnasium was located. There the Gestapo had set up offices. They took the hostages off and we continued our travelling. Every few minutes we stopped and would ask the pedestrians about the situation. On one occasion we received the following answer, “they don't bother us, only the Jews who have deserved such German-style of treatment for a long time.” With a sad feeling and full of fear for our future, I arrived, together with the entire convey of Polish prisoners, at the locality Kobierzyn near Krakow.

Until our arrival at Kobierzyn we experienced a lot of suffering due to the tremendous extremes of temperature. First it would be hot and then cold. I also met a couple of Polish reserve officers from Brzozow. One of them was the son of the director of the health insurance office in Brzozow: I reminded him that just two months ago, he had stood together with other young gentiles in front of Jewish stores refusing entrance to the Christian customers…

We had with us a number of soldiers dressed in civilian clothing, as there had been no time to conform to the military regulations of putting them in uniform. Among the reserve corps was a young officer in civilian life employed in the oil fields in Grabownica near Brzozow. This officer brought to my attention that a “spy” was being detained that had a Jewish appearance. This man was dressed in civilian clothing and had no identification documents. I followed the officer to where the “spy” was being kept. This man was actually a Jew from Kolomyja, Galicia and his family name was Herzl. Not only because he was a Jew, but also because the name Herzl aroused in my memory the particular feelings associated with that famous name Benjamin Zeev (Dr. Theodore Herzl); I tried to explain to the officer that it was absurd to suspect a Jewish person of spying for the German government. He was immediately released and remained with us at the prison camp in Kobierzyn.

Finally we reached the prisoner-of-war camp at Kobierzyn. Our arrival was not spread with roses. Instead, there were machine guns in all corners aimed directly at the new arrivals. The first order came from the commander.

“Austeugen” (fall out). Then came the second order.

“Volks Deutschen Austreten” (native Germans, fall out).

“Ukrainer Austreten” (Ukrainians fall out) and finally.

“Juden Austreten” (Jews, fall out).

The remaining Polish prisoners, as well as Ukrainian, Volks Deutsch and Jewish prisoners were all put in separate barracks. We Jews were the last. A German under officer approached our group and asked if there was an under officer present among the Jews. At first we hesitated to answer. However, after the question was repeated I stood up and reported that I was a under officer in the Polish army.

I received an order to count the Jewish prisoners (253 in number) as well as to be in charge of the proper location of the prisoners in barracks number 23. I put the order into motion. The barracks contained several rooms, all of them with straw spread on the floors. The order was carried out immediately. Right after that several German officers came to our barracks and examined us “from top to bottom”. One of them asked who among the prisoners spoke German perfectly. A young Jewish man named Eisenberg from Bielsko came over and claimed that he spoke German well. He was a tall, good looking man with a French style mustache and pleasing personality. A German officer interrogated him and on the spot assigned him as interpreter to the German command. It is important to take note that the young man, Mr. Eisenberg in his position of interpreter was favorable to the Jewish prisoners and with his kind attitude was always trying to help his distressed fellow Jewish friends.

A couple of days later a German under officer came to our barracks and asked for twenty persons

[Page 97 - English]

to clean up the railway station in Krakow. I was assigned responsibility for the group. We came to the railroad station in Krakow and the German under officer selected five prisoners from the group, gave them the proper equipment, and showed them the work they were to perform. The remaining fifteen persons were sent to the wagons located on the rails, and at the same time he gave them permission to take out the food supplies placed in the wagons. This kind of statement surprised us very much and we reacted with suspicion and distrust. However, we concluded from our observations that he was a very respectable man. After our work was completed, this under officer brought us to the German military kitchen where we received a good meal. We were accompanied, though with harsh anti-Jewish expressions from the by-standing German soldiers. The German under officer returned us to the camp and gave us permission to take with us the food products found in the wagons. Among the Jewish prisoners were several strongly religious Jews who refused to eat non-kosher food, therefore we gave to them the items suitable to their needs.

The following day when the gentile prisoners found out about our “good luck” on the railroad station, they sought out the German under officer in charge and told him that they would perform the work even better than the Jews. The under officer ignored their request with the following answer, “Those who worked yesterday will also work today and the day after for as long as it will be necessary.” Several days later new staff arrived for the purpose of taking over the guard post for the camp and in this way “our seven good years” came to an end.

The new staff came especially to block number 23 to take a look at the Jewish prisoners. Overhearing their conversation, I heard the following remark, “Look Hans, the Jews don't have crooked noses as shown in our newspapers, and also their language is in a German dialect.” (He was referring to Yiddish).

It is important to emphasize that this was the beginning of the German occupation of Poland.

The hostile attitude towards the Jews from the Ukrainians, Volks Deutch, and the vast majority of the Poles, exceeded the German unfriendliness towards the Jews. I remember an incident where a Ukrainian prisoner came to a German officer with abusive accusations against the Jews. The German officer did not understand his language, so he called upon Mr. Eisenberg to intercept. Eisenberg listed to the Ukrainian's story and purposely misinterpreted in favor of the Jews, quoting him as saying, “The German occupation of Poland will not last long, because the French and English governments have already declared war on Germany.” The German officer became furious and beat up the Ukrainian prisoner. This was also a lesson for all other non-Jewish prisoners to keep their mouths shut.

Among the prisoners were some Jews who had concealed their origin and as “non-Jews” lived together in the barracks with the gentiles. From these prisoners we received information regarding the attitudes and opinions of our “brothers-in-arms” of yesterday towards the Jews.

One day an order came that all prisoners with an occupation of farmer wee to be released because the German occupants needed to collect the harvest from the fields. Several days later the first convoy left camp with the discharged prisoners, among them was a Jew named Pinkas Rek, from Jasienica near Brzozow.

Rumors circulated that at the beginning of the next week all prisoners would be transferred to Germany.

At this point, together with six other Jewish prisoners from Boryslaw and Drohobycz, I made the final decision to do my utmost to escape from the camp and avoid transfer to Germany.

Together with six Jews, we ran away. We separated from one another and agreed to meet at 10 o'clock that night in the railroad station of Krakow.

I went through the fields and noticed from afar a small house. When I came to the house, I knocked on the door; the door opened and out came a middle-aged Pole. He brought me inside and asked me if I was hungry. First of all I told them that I was a Jew. His reaction was positive, declaring that it didn't make any difference to him whether Jew or non-Jew especially when I was wearing the uniform of the Polish army. I had a warm reception and plenty to eat and drink. His sister-in-law accompanied me to the tramway via Podgorze. It was much safer to be in the company of a woman. That man's occupation was a bricklayer. Later, during the Soviet occupation of Lwow, I sent him packages out of gratitude for the deed. I entered the tramway going to Podgorze because I intended to visit my mother's cousin, Samuel Katz, once the secretary to the well-known Jewish Zionist leader, Dr. Joshua Thon. Several German officers entered the tramway

[Page 98 - English]

and I was duty bound to give them a respectful salute. Even as a loser the obligation was the same. They returned the salute. No one bothered me and I did not suffer from any mishaps. By nightfall I reached my mother's cousin. I even had a chance to observe the Jewish stores closed and on each store there hung a note “Jewish business” with a Star of David framed. The family of my mother's cousin did not expect me and their joy at seeing me free from the camp was enormous.

We talked a lot and from them I found out about the situation of the Jews in Krakow which was already very tragic. They asked me to stay the night, but I refused, because I was aware that the city of Przemysl was divided; the eastern side of the river San was occupied by the Soviet Union and the western side by the Germans. Without losing time, I departed from them and went towards the main railroad station. There I met my six fellow-Jewish friends, and we entered the train to Tarnow. There we got out and had to wait for a train going to Rzeszow. At this particular moment I encountered a Polish man from Brzozow who came over to me and asked if I was going there and, if so he was willing to take me with him. My answer was that my wife and child were in Przemysl and that I was going there. He solemnly promised to give my regards to my mother in Brzozow; she was still living there at this time. The Polish man kept his promise and upon his arrival in Brzozow contacted my mother and passed on my regards. He gave my mother exact details to prove that everything was all right with me and that I had left for Przemysl to join my wife and child.

After a couple of hours wait in Tarnow at the station we got on a train for the city of Rzeszow. At the nearest station, Debica, a Gestapo official entered the train and asked for permit documents. Since the number of prisoners was quite large he was unable to check each document on an individual basis, therefore he asked us to raise the permit papers with our right hand. After that procedure he left and we could breathe freely once again. In a few hours we arrived at the Rzeszow station where we became aware of the horrible misfortune befallen the Jews of that city. Young Jewish intellectual girls in their best dresses were forced to scrub the floors and even to wash the stones of the railroad station and polish the boots of the German soldiers. The Jewish population's suffering in Rzeszow was chilling news.

At this point we, along with several hundred former Polish soldiers, were loaded into a cargo train and told that it would go only to Jaroslaw as the bridge over the river San in Przemysl was destroyed. After arriving in Jaroslaw we were quartered in a hotel near the railroad station. The hotel had been partly damaged as a result of the bombardment, but several rooms remained intact. We slept on straw spread on the floor.

In the middle of the night an enormous Gestapo man came in and shorted, “Are there any Jews here?” No one answered and he left. About an hour later another Gestapo man came in and asked the same question, adding the following remark, “Watch out, there better be no Jews here.” He looked around and disappeared.

Around 10 o'clock in the morning we marched to the edge of the river San where hundreds of civilians were assembled as well as former Polish soldiers, all of whom were put near the temporary wooden bridge over the river.

Then a conference started between the Gestapo and the Soviet authorities which took place in the middle of the wooden bridge. We received an order from the Gestapo to raise our permit papers high and with the proper signal of an extended hand; the time came to cross to the other side of the river into the Soviet occupied zone.

When I found myself on the other side of the bridge the first thing I said was “Baruch Shepitranu” (Thank God, that I am rid of them)…Fortunately, there was a Jew waiting there with a horse and carriage for passengers. The way to Przemysl was a long one because of the damaged bridge.

We travelled an entire night before we arrived at Przemysl. We came to the street where my in-laws lived and with them, during the war, also lived my friend Leon Fass from Brzozow. He was aware of my arrival and hearing my voice, immediately informed my in-laws and my wife that I had arrived. Our greeting was an emotional one, dramatic as well as cheerful.

Here is the end of the first chapter of my meeting with the Germans, when I had the “privilege” of being a Polish soldier. Even at that time we did not see eye to eye with the beastly German murderers. All of that is written of later in the next chapter of my life during the war, which, as is well-known, was more tragic and horrible than my previous experience.

(Translated by Fela Ravett)

This material is made available by JewishGen, Inc.

and the Yizkor Book Project for the purpose of

fulfilling our

mission of disseminating information about the Holocaust and

destroyed Jewish communities.

This material may not be copied,

sold or bartered without JewishGen, Inc.'s permission. Rights may be

reserved by the copyright holder.

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Brzozow, Poland

Brzozow, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Yizkor Book Director, Lance Ackerfeld

This web page created by Max G. Heffler

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 9 Jul 2013 by MGH