|

|

|

Leibner Family Story told by William Leibner

At the end of the war Jews lived in constant fear. Some Jews who returned to their native cities and demanded the return of their flats or possessions were physically threatened or even killed. Jews were being openly attacked and the countryside was particularly hostile to Jews. Every transport of repatriated Polish citizens from the Soviet Union increased anti–Jewish sentiments that were exploited by the right wing political organizations who were trying to overthrow the established Communist dominated government. This Polish government was encouraging people to move to the new areas that had been created through negotiations after the war.

My father, Jacob Leibner had moved from Nowy Zmigrod to Krosno, where he married my mother, Ser Lang who was also born in Zmigrod. The marriage was arranged. Sons Wolf or William and Yehuda or John were born in Krosno where we stayed until 1940 when my parents decided to leave and cross the border illegally to the Russian occupied part of Poland. We returned to Krosno in 1945 but found few Jews there and decided to move to Walbrzych or Waldenburg in the new territory. We moved to find safety for Krosno was not safe for Jews.

The government wanted to quickly settle these areas and offered all kinds of benefits and apartments to new arrivals. Many other Polish Jews were moving there and creating new Jewish communities.

Our family was given an apartment in a working class neighborhood, number 39 Red Army Street, that had been vacated by a German family. The German population was forcibly removed from the city and send back to Germany. The German family had left almost everything in the apartment. By the door hung work clothes indicating that the owner was a coal miner. We children tried on the hat for size and played with it. We also found albums with pictures of the German army on the march across Europe. There were several German books on a shelf. The apartment was moderately furnished and livable.

|

|

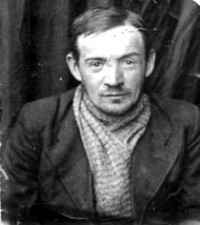

| Jacob Leibner in 1945 |

The first Jews arrived in the city about 1830. Jews officially received permission to establish a community in 1862 and by 1880 there were about 328 Jews in the city. The community purchased a piece of land and dedicated it in 1882.The next year, the synagogue was finished. Later on a community center would be added to the synagogue. By the early 1930s, anti–Semitic acts were on the rise, with Nazi youth groups verbally abusing Jewish businessmen. These acts eventually escalated into physical violence and, as a result, Jews started leaving Waldenburg or Walbrzych. By 1939, only 24 Jews still lived in the town. The synagogue was burned down on Pogrom Night The few remaining Jews of the city were deported after 1942 and perished. At the end of the war there were no Jews in Walbrzych.

Following the war, many Jews began to settle in Walbrzych especially Jews that spent the war years in Russia. The Polish government, the local branch of the Central Committee of Polish Jews and the JDC helped in the absorption of the new Jewish arrivals. Many cooperatives ventures were formed by Jewish craftsman. Jews were hired by the various municipal offices mainly in the medical field. The “Vaad Hakehilot” or religious council opened an office and a synagogue in Walbrzych that we attended. Rabbi David Kahana, chief chaplain of the Polish army addressed the Jewish community in Walbrzych. Eighteen hundred Jews found employment in Walbrzych not long after the war. Close to 800 of those were miners or glass founders. A Jewish school was opened where instruction was given in Yiddish and Polish, it had an enrollment of 170 children. Other Jewish institutions in Walbrzych provided care for 432 children. Walbrzych had a Yiddish library, a variety of cultural clubs, and Zionist organizations that were very active. Still the Jews did not feel secure in Walbrzych. Every anti–Semitic event increased our fears. Most anti–Semitic events were not reported in the press but spread by word of mouth. The fact that Jewish institutions had to be guarded by armed men indicated the seriousness of the situation.

|

|

| Members of the Zionist parties bought a “Shekel” that enabled them to vote for their party in the general elections of the Zionist World Congress. The shekel number 22467 was sold to Jakob Leibner residing at 39 Red Army Street in Walbrzych Poland. The amount paid was 70 zlotys, Polish currency. |

My father was very active in the Ha–Poel Ha–Mizrahi or moderate religious Zionist movement. Meetings were held in our flat. Some young people even slept at our place. The discussions frequently revolved around going to Palestine or staying in Poland and hoping for the best. As time went by, I noticed that items disappeared from our flat. When I asked about it, I was told that new items would be purchased to replace the old ones. Of course, no new items were bought. Instead the family acquired back packs and warm clothing as well as a substantial amounts of food bought on the black market. Everything was packed and we were told that we were going hiking in the countryside. We took the train at the Walbrzych station and headed to the country. We noticed that some other passengers had similar back packs. We traveled a short distance and descended from the train and walked toward the forest. Father led the way and we followed. We rested in a small clearing where other people joined us. Towards evening, a few young men appeared and introduced themselves as Brichah agents. One of them spoke in Yiddish and said: “You are now in the border area. We will be moving in a single file. No talking, smoking or singing. Always stay close to the person in front of you. Within a short time we will begin to move.” It was dark as we began to walk and walk. We stopped for a rest and continued to walk in the forest. At the crack of dawn we left the forest. The Brichah leaders told us that we were in Czechoslovakia. We sat down and ate some of the food that we had brought along. Some people smoked or tended to their needs. The Polish Brichah members bid us farewell and returned to Poland while Czech Brichah members appeared and greeted us with the words “Shalom Aleichem”.

We started to walk towards the country road and saw Czech farmers working their fields. We soon reached a small railway station and received train tickets from the Brichah men. We boarded a small train that carried us deeper into Czechoslovakia. We reached a big railway station where we left the small train and boarded a larger passenger train. Our compartment contained a couple that spoke Yiddish but not Polish Yiddish. My father told me that they were Slovakian Jews because of their Yiddish speech pattern. The train rolled for hours and we finally reached Prague where trucks picked us up and took us to the UNRRA transit camp on the outskirts of the city. The camp was immense and subdivided according to nationalities. There was an Italian camp, a Polish camp, a Spanish camp, a Ukrainian camp and a Jewish camp. The Jews came from all over Poland and made up the majority of the camp. There were also Russian, Slovakian, Baltic, and Hungarian Jews. We registered at the office, had medical exams and were issued paper identity cards that enabled us to eat in the dining room. We were assigned a corner of one of the barracks. The children received extra food including milk and eggs.

While UNRRA ran the camp and arranged transportation for the thousands of refugees that were headed in all directions. The JDC also had a large staff to help the Jewish refugees, and the Red Cross had several stands in the camp that provided new arrivals with hot drinks. The Jewish refugees stayed in the camp for varying lengths of time. Excursions were organized for camp residents to the Prague Jewish quarter including the synagogues and the famous Jewish cemetery. We were even able to pray at the Old New synagogue. The local people were friendly and we were favorably impressed with the city.

|

|

| The Jewish quarter in Prague with the famous clock that has Jewish letters instead of numbers |

|

|

| The old Jewish cemetery in Prague |

|

|

| The interior of the old–new synagogue |

We stayed at the Prague camp for close to five weeks. We were then ordered to pack and assemble in the camp yard where a truck picked us up and took us to the railway station. We were a sizable group but were dispersed throughout the train that traveled for many hours in the direction of the German border. Towards evening we left the train and headed into a wooded area where we were divided into several groups each headed by a Brichah agent. We walked for several hours and reached a main road where there was a convoy of empty military trucks. Each group was assigned to a truck. Our driver was a black soldier. This was the first time that I had ever seen a black person. He was very pleasant and gave us children Hershey chocolate bars and chewing gum. We did not know what to do with the gum so he very patiently showed us how to open the wrappings. The convoy moved out of the border area and headed deeper into Germany. We reached a transit camp where we remained for a short time and moved to another D.P. camp. Finally, our transport arrived to the Pocking DP camp located near the city of Passau in Bavaria within the American military zone of occupation in Germany. The camp was a former German Air force base and there were still plane parts scattered along the runways.

We registered, were given medical examinations and forms to fill out. JDC officials were there to help with the paper work that was mostly in English. The refugees spoke many languages although Yiddish was the predominant language. All the streets and official buildings had Hebrew names. . We were assigned a room in a barracks and given meal tickets to use at the main kitchen.

The camp was run by an elected committee that represented the Zionist political parties in the camp from the Revisionist to the Hashomer Hatzair party. Each party had a youth division that attracted the youngsters. Sports were highly encouraged as was the study of the Hebrew language. We were kept very busy with all the activities. My father was placed in charge of providing wood for the camp kitchens, schools and offices.

We spent several months at the Pocking camp when one evening two young Brichah agents came to our barracks and told us that within ten days we were to meet at a certain place next to the school yard where a truck would take us to the train station. We could have refused to go and remained in the camp. But we did not want to stay in Germany and neither the Germans nor the American military authorities wanted us. So we decided to take our chances and go with the Brichah to France. About three dozen people left the camp together with a Brichah official carrying a collective pass. We boarded a train that traveled for several hours before reaching the French military zone in Germany. French soldiers examined our papers and searched us thoroughly. We were then returned to the train and continued our journey. At some point later we left the train and headed to a large inn located near the Franco–German border. Soon other Jewish refugee groups arrived. Then we were all instructed to walk single file and maintain absolute silence. We walked this way for the entire night. At a given point we crossed the French–German border near the city of Metz, France. There along the road waited a column of trucks. Each group proceeded to a truck that immediately started the engines and left the area heading south. Our truck refused to start. All efforts failed. The Brichah leader told us not to worry, the French border police would soon arrive. Meanwhile he collected all papers, monies and letters and destroyed them. He told us that he and the driver would leave us and insisted that we were safe in the truck. At dawn the French police arrived and took us to the Metz prison where interrogations began. We all played stupid. The French soon realized that we were Jews since some of us refused to eat the meat we were given except for vegetables, bread and butter. We were in the local jail for about two weeks until JDC officials from Paris arrived and explained to us in Yiddish our serious situation. We had violated many French laws and were in an area forbidden to foreigners. They collected our information and promised to help. A few days later, they returned and informed us that we had relatives in France that were willing to sign papers assuming all responsibility for our stay in the country. Two French policemen escorted us from Metz to Paris where they released us in the custody of our French family.

The JDC in Paris assigned a social worker to help guide us in France. He explained in Yiddish with a French accent that we would have to report to the French police each week and would be watched closely. We must live quietly, no contact with the Brichah or other illegal groups, no contact with political parties especially Zionist parties and no ties with the other detainees in Metz. This was a heavy price to pay but the threat of deportation to Poland was real and my parents were dead set against returning to Poland.

The JDC also located Leibner relatives in the US who had been looking for us. Our relatives had filed papers and bonds to bring the sole survivor to the US, but the papers were sent to Warsaw and Jacob Leibner was in Paris. Letters went back and forth between the JDC offices until the papers were located and brought to Paris. Meanwhile, the French Justice ministry caught up with us. We had to appear in court and were charged with a host of criminal charges including entering the country illegally. The French Jewish organization Alliance Israelite provided legal assistance and argued that we would soon be leaving France. The case adjourned. Meantime, JDC taught my father a trade and we children were sent to a private school named Lycee Yabne that still exists today. Finally in 1951, we were invited to the American consulate in Paris and interviewed individually. The official spoke to me in English and I was able to answer him since I had studied English at the Lycee. He was surprised and in a moment of frankness said: “You see that big heavy folder on the desk, these are your family papers and police reports”. I asked what police reports and he said every time you went to the police to sign the required form of temporary residence or the court litigations, we received a copy. He added with a smile: “not a pretty dossier”. The implication was quite clear, the consulate did not want such people to enter the US. But the JDC and our relatives brought enough pressure and we were finally to be admitted to the US.

Meanwhile convoys of trucks full of Jewish refugees continued to roll in a southerly direction towards the port of Marseilles. Within a short time, the American ship named “President Warfield” renamed the “Exodus 1947” would take aboard about 4200 Jewish illegal passengers including 655 children from the Jewish refugee camps around Marseilles and sail from the port of Sete near Marseilles to Palestine [1].

|

|

| View of the illegal immigrant ship, the “President Warfield” renamed the “Exodus 1947”, docked at Port–de–Bouc, France, prior to its voyage to Palestine. |

Our family remained in Paris, France, under the protection of the JDC, which insisted that our transit in France would be very short since there was a large Leibner family in the United States that had signed the necessary legal papers indicating that they guaranteed to support us in the United States. Meanwhile, my father was sent to learn to make pants and we children were registered to attend school. The JDC rented a two–room flat

|

|

| Wolf Leibner in Paris |

|

|

| Yehuda Leibner in Paris |

for us. We lived with the hope that any day we would be heading to the United States. The days turned to weeks, months and years. Finally, we were called to the American Embassy in Paris and told that we could proceed to the United States, that our names had reached the entrance list. The JDC

|

|

| Seril Leibner–Lang |

|

|

| The Leibner family is leaving Paris for Bremerhaven, Germany where they would board the troop ship named General M. B. Stewart heading to New York City. Left Yehuda Leibner, center Serl Leibner–Lang, Yaakov Leibner and Wolf Leibner |

made all the necessary preparations and we left Paris for Bremerhaven in Germany where we boarded an American troop ship named General M. B. Stewart. The ship headed to New York City with refugees who had been admitted to the United States. The ship docked in New York November 30, 1951, see ship manifest below, where the Leibner family waited for us. Our traveling saga came to an end.

|

|

| The manifest of the “ General Stewart” lists the Leibner family entering the USA. |

Footnotes

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Brichah

Brichah

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 23 Apr 2017 by JH