|

|

|

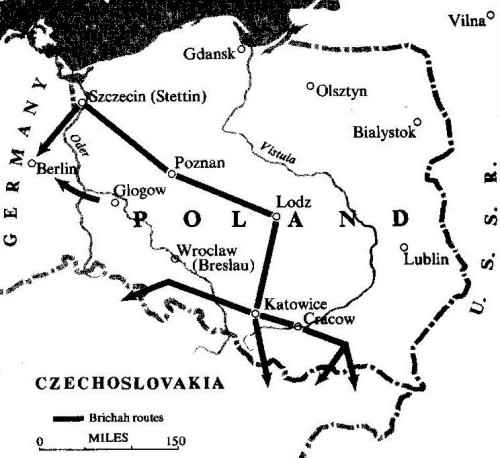

Following the Kielce pogrom thousands of Polish Jews headed to the Polish –Czech and Polish–German borders.

|

|

| Brichah roads leading Polish Jewish survivors out of Poland. In the North, the roads from both Szczecin or Stettin, and Glogow, led to the Soviet zone of Germany. Roads from Wroclaw or Breslau, Katowice and Krakow led to Czechoslovakia. |

In March 1939 Germany occupied the remaining parts of the Czech provinces of Bohemia and Moravia, and a puppet Slovak state was established in Slovakia. As already mentioned, some Jewish survivors who returned from the camps to their homes in Poland, Slovakia, Lithuania and Latvia (and elsewhere) decided to leave these new homes and return to the labor or concentration camps (converted into refugee centers) in Austria and Germany. Most of the returnees were escorted by the Polish Brichah to the Polish–Czech borders where the Czech Brichah headed by Moshe Govsman awaited them. Govsman was a Palestinian farmer familiar with military operations and he ran the Brichah like a military unit. Some of the Jewish returnees went to Romania as mentioned earlier while others proceeded to Czechoslovakia under Brichah guidance. There were also private groups that organized border crossings. In 1945, about 5,000 Polish Jews left Poland,

|

|

crossed illegally into Czechoslovakia and then continued to Germany and Austria. Baltic, Ukrainian, Slovak, Hungarian and Romanian Jews joined this ever–growing trickle of illegal Jewish Shoah survivors who entered Czechoslovakia.[1] Most of them reached the small Czechoslovak town of Nachod where the Czech Repatriation Office and the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC) had established a small reception camp for refugees.[2] The hamlet had 20 Jewish inhabitants who had survived the war out of a pre–war community of 300 Jews. These Jews helped the refugees on their way. The camp consisted of two barracks but would expand with time. The exit of Jews from Poland would continue until 1972 although through regular channels between Israel and Poland starting in 1949. About 243,511 Jews would leave Poland (see chart below[3]). Most of them emigrated to Israel while others went to the United States, South America and Europe.

|

|

Column on the right represents period from 1944–May 1945. Next column represents Brichah transports. Next column represents independent smuggling operations. Last column represents total number of Jews that left Poland. From 1944–May 1945, 5000 Jews left Poland. From May–June 1945, 10,500 Jews left Poland From July– December 1945, 38,775 Jews left Poland During 1946, 88,716 Jews left Poland. From January–February 1947, 2,730 Jews left Poland. |

Between 1945 and 1947, 127,722 Jews were safely taken out of Poland by the Brichah. This was quite an achievement for a relatively small organization that worked in secret with the financial help of the Jewish Agency in Palestine and the JDC in Poland. Many of the Brichah members volunteered and barely covered their minimal expenses. In places where JDC had offices, Brichah members would be on their payrolls. The Brichah volunteers faced serious dangers as they illegally crossed the various borders. For example, on May 2, 1946, a transport of Gordonia Zionist youth members was ambushed near Nowy Targ, Poland, and murdered along with their Brichah guides. Still, the Brichah continued with its task of leading Jews out of Eastern Europe to Central Europe.

Joseph Schwartz, Director of JDC European Joint Operations became alarmed at the large numbers of Jews leaving Poland. Schwartz was a brilliant and exceptional man. Known as “Packy” to those close to him, he was born in Ukraine and moved to Baltimore at an early age. A distinguished educator and scholar and an authority on Semitics and Semitic Literature, Schwartz received his doctorate from Yale following his graduation from the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Seminary of Yeshiva University. Schwartz taught at the American University in Cairo and at Long Island University and then served as Director of the Federation of Jewish Charities in Brooklyn. He served the JDC from 1939–1950 and then went on to become the Executive Vice Chairman of the United Jewish Appeal and later the Vice President of Israel Bonds. Schwartz died in 1975.

|

|

Schwartz saw the growth of the illegal border crossings and decided to call on Gaynor Israel Jacobson who was in the USA recuperating from a serious disease he contracted in Greece. Jacobson had proved himself capable of handling very difficult situations. Schwartz saw that he needed an exceptional man to head the office in Prague as the number of Jewish refuges kept growing in Czechoslovakia.

In March 1939 Germany occupied the remaining parts of the Czech provinces of Bohemia and Moravia. According to the official records there were 118,310 Jews in these provinces according to the Nuremberg laws[4]. Only 3010 Czech Jews survived the Shoa most of them were married to non–Jews[5]. As already mentioned, some Jewish survivors who returned from the camps to their homes in Poland, Chechia ,Slovakia, Lithuania and Latvia and Ukraine decided to leave these new homes and return to the labor or concentration camps (converted into refugee centers) in Austria and Germany. Most of the returnees were escorted by the Polish Brichah to the Polish–Czech borders where the Czech Brichah headed by Moshe Govsman awaited them. Govsman was a Palestinian farmer familiar with military operations and he ran the Brichah like a military unit. Some of the Jewish returnees went to Romania as mentioned earlier while others proceeded to Czechoslovakia under Brichah guidance. There were also private groups that organized border crossings. In 1945, about 5,000 Polish Jews left Poland, crossed illegally into Czechoslovakia and then continued to Germany and Austria. Baltic, Ukrainian, Slovak, Hungarian and Romanian Jews joined this ever–growing trickle of illegal Jewish Shoah survivors who entered Czechoslovakia.[6] Most of them reached the small Czechoslovak town of Nachod where the Czech Repatriation Office and the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC) had established a small reception camp for refugees.[7] The hamlet had 20 Jewish inhabitants who had survived the war out of a pre–war community of 300 Jews. These Jews helped the refugees on their way. The camp consisted of two barracks but would expand with time. The exit of Jews from Poland would continue until 1972 although through regular channels between Israel and Poland starting in 1949. About 243,511 Jews would leave Poland (see chart above). Most of them emigrated to Israel while others went to the United States, South America and Europe.

Between 1945 and 1947, 127,722 Jews were safely taken out of Poland by the Brichah. This was quite an achievement for a relatively small organization that worked in secret with the financial help of the Jewish Agency in Palestine and the JDC in Poland. Many of the Brichah members volunteered and barely covered their minimal expenses. In places where JDC had offices, Brichah members would be on their payrolls. The Brichah volunteers faced serious dangers as they illegally crossed the various borders. For example, on May 2, 1946, a transport of Gordonia Zionist youth members was ambushed near Nowy Targ, Poland, and murdered along with their Brichah guides. Still, the Brichah continued with its task of leading Jews out of Eastern Europe to Central Europe.

Schwartz saw the growth of the illegal border crossings and decided to call on Gaynor Israel Jacobson who was in the USA recuperating from a serious disease he contracted in Greece. Jacobson had proved himself capable of handling very difficult situations. Schwartz saw that he needed an exceptional man to head the office in Prague as the number of Jewish refuges kept growing in Czechoslovakia.

Israel Gaynor Jacobson was born in Buffalo, New York on May 12, 1892 and grew up in a hostile anti–Jewish environment. He reversed his first and

|

|

He had a strong background in social work and joined the JDC in 1944. Schwartz soon sent him to Italy to handle the special refugee problems in Italy. Jacobson accepted the post of Prague JDC Director and arrived there in April 1946.[8] Jacobson spoke several languages, notably Hebrew and Yiddish. He met with Brichah and Mossad officials in Prague who had their offices in the same building as the JDC.[9] He then began a series of meetings with key contacts in the Czech capital, including Jan Masaryk, Czech Foreign Minister, Zdenek Toman, head of state security and Klement Gottwald, leader of the Czechoslovak Communist Party. The JDC knew that Masaryk was particularly friendly to the Jewish people. In 1940 when a Czechoslovak Government–in–Exile was established in Britain, Masaryk was appointed Foreign Minister. He remained Foreign Minister following the liberation of Czechoslovakia as part of the multi–party, communist–dominated National Front government. The Communists under Klement Gottwald saw their position strengthened after the 1946 elections but Masaryk stayed on as Foreign Minister. Shortly after the Communists took over Masaryk supposedly committed suicide by walking out of his office window.

The Czech relationships would become critical to the establishment of the State of Israel. In 1948 Czechoslovakia sold arms to Israel during the Arab–Israeli War. Masaryk would sign the first contract on January 14, 1948.

When they first met, Jacobson thanked Masaryk profusely for the help that Czechoslovakia was extending to the Polish Jewish refugees.

|

|

and for the assistance to the various Jewish social agencies that dealt with the Czech Jewish survivors. Masaryk told Jacobson that he should also meet Toman, head of security at the Ministry of Interior, regarding Jewish matters. Jacobson did not know at the time that Toman was Jewish (very few people in Czechoslovakia knew this fact).

|

|

According to author Tad Szulc, Masaryk even called Toman to tell him that Jacobson would visit him.[10] Toman received Jacobson in his office. Jacobson began to explain the Jewish situation in Europe and especially in Czechoslovakia. The two men hit it off, both coming from similar backgrounds although different countries. Both had experienced vicious anti–Semitism growing up. Toman promised to help and assured Jacobson that Polish Jewish refugees would continue to cross Czechoslovakia as long as he was Chief of Security.[11]

Toman, born Asher Zelig Goldberger, was the son of David and Rosalia Goldberger. Born March 2, 1909 in Sobrance (now part of Slovakia), he finished elementary school in Sobrance and high school in Uzhhorod. He entered the law faculty of Charles University in Prague in the winter term of 1927–1928 and graduated with a law degree in 1933. Toman joined the Communist Party at the university. He married Pesla Gutman on January 26, 1935, in Lodz, Poland and spent the war years in England where he was a member of the Czech government–in–exile. He returned to liberated Czechoslovakia, headed the State Security Office and was a member of the Czech Repatriation Commission. Toman helped the JDC and the Brichah organization transport thousands of Polish, Hungarian, Romanian, Czech, Slovak, Ukrainian and Baltic Jews across Czechoslovakia to the DP camps in Germany, Austria and Italy. Toman officially stated that he helped 250,000 Jews reach safety. In 1948 that number reached about 300,000. In 1948 Toman was arrested but fled to West Germany, then to London and later to Venezuela where he joined the family business, Gexim, established by his brother Armin Goldberger. On June 23, 1949, he was condemned to death in absentia and lost all his property. Toman's appeal to the Czech Supreme court was rejected on April 3, 1950. His wife supposedly committed suicide on May 8, 1948 and his young son, Ivan Toman, disappeared forever.

Jacobson also made connections with Minister of Interior Vaclav Nosek, Minister of Welfare and Labor Nejedly and other Czech political leaders. These new relationships were soon tested when Yochanan Cohen, an active Palestinian Brichah leader was sent to Poland to help run the Polish Brichah. He led a group of Jews out of Poland through Czechoslovakia.[12] Their papers stated they were Austrian citizens returning home from captivity. At the Czech town of Moravska–Ostrava, the entire group of Jews was arrested and thrown in jail on suspicion of being Austrian Nazis. The Czech Chief of Police was not well disposed to Austrians or Germans and took a dim view of the group. The Jewish refugees were locked up in jail and allowed no telephone calls or notes to the outside. Then Cohen ordered someone in the group to play sick. The man was taken to an infirmary where by chance he met a Jewish doctor. He told the doctor their story and begged him to help. The doctor apparently informed the Jewish community of the situation, since the head of the community presented himself the next day at the local police station and asked the authorities to allow him to speak to the arrested Jews. He soon convinced the police that the arrested people were Polish Jews. The next day they received packages of food from the small Jewish community of Ostrava. The community also informed the JDC office in Prague of the situation. Jacobson, heard the news and immediately called Toman for help. The group was freed and headed to Austria as planned.

On another occasion, Yochanan Cohen crossed the Polish–Czech border with a transport of Polish Jews. They had a collective pass, forged in Krakow by the Polish Brichah, stating that they were Greek prisoners of war heading home. The Polish border guards ignored the group as did the Czech border guards. Suddenly a Soviet officer attached to the Czech border patrol asked Cohen, the leader of the group, to say something in Greek. Cohen would later write, “I kept my cool and said &147;Itgadal veitkadash shmei rabba,” the officer replied &147;amen.” Apparently the Soviet officer was Jewish and recognized the Aramaic words that open the “Kaddish” prayer for the deceased. He even said “amen,” indicating that he was familiar with the prayer and the usual response to the prayer. The group continued its illegal journey.

Anti–Jewish pogroms occurred not only in Poland but also in Slovakia. The first pogrom took place in Kosice on May 3, 1945, later in the summer in Presov and in Toplcany on September 24, 1945. Pogroms continued to plague Slovakia until 1948. The causes of the pogroms varied from place to place but always revolved around the idea of Jews trying to control the place or Jews operating a black market. The Slovak pogroms never reached the intensity of the Polish pogroms but it is estimated that 36 Jews were killed and about 100 injured in the various attacks against Jews in Slovakia following the war.[13] Prior to the war the Jewish population of Slovakia numbered about 77,000; following the war there were about 33,000 and the number steadily declined.[14]

The Jewish population, especially the youth, saw no future in Slovakia and, seeing the constant transports of Jews out of Poland, joined the exodus. Most of the transports that left Poland crossed the border and reached the camps at Nachod and Broumov in Czechoslovakia. Here the refugees rested and were then shipped to Bratislava where they crossed to Austria or were sent across Czechoslovakia to the West German border at the hamlet of Asch. German Brichah members took the transports and directed them to the DP camps, mainly in the American zone of occupation. The Bratislava transports crossed the Austrian border and were escorted by the Austrian Brichah to the DP camps in Austria. Most of the transports stayed a few days in Czechoslovakia and then left the country. The Nachod camp was the largest camp administered by the Brichah and as in other camps, the JDC provided food, medicine and clothing if needed. There was another, smaller camp located near the village of Broumov that also handled Jewish refugees from Poland.

|

|

With the increased flow of illegals, Jacobson increased the food stocks and facilities at the camps. Most transports avoided Prague, the Czech capital, for fear of attracting attention and publicity. The Brichah, the Czech government and the JDC wanted to avoid attention because British and American pressure was building to tightly close the borders. The British Ambassador to Prague lodged many protests demanding the closure of the borders, but the Czechs procrastinated.

Prague was the center of a well–equipped communication system that connected all Brichah offices throughout Europe and Palestine. The communication equipment had been brought to Prague with the permission of the government, that is, the secret service headed by Toman. The office and the entire Brichah organization in Czechoslovakia was headed by Moshe Govsman who worked in close cooperation with Jacobson as did Lev Argov in Bratislava. Both were Palestinian Brichah men familiar with Czechoslovakia.[15] Lev Argov was born in Czechoslovakia and spoke the language fluently. He left Czechoslovakia prior to World War II and settled in Palestine where he actively participated in military underground activities. He was also an expert in international finance and foreign currencies.

Britain and the United States saw that their protests against the open borders were not succeeding, so they decided to use another tactic. They put pressure on UNRRA, which they controlled, to stop or effectively slow the reimbursement payments that Czechoslovakia was supposed to receive for its outlays of money for the Jewish transients. In talks with the Czechs, Elan Rees, local UNRRA chief, had intimated that UNRRA would assume most of the costs of transportation, temporary lodging and food for the transient Jewish refugees. But there was obvious discrimination. The UNRRA office readily paid transportation bills and other expenses for the transport of non–Jewish refugees while payment for transport of Jews dragged on. UNRRA officials easily determined which was which. Almost all the passengers on transports originating at the Polish borders heading toward Austria or Germany were Jewish. The Czechs were shocked when they learned that UNRRA refused to pay bills related to the transport of the Jewish refugees. The non–payment of bills increased the expenses of the Czech government.

Toman, as Czech Deputy Interior Minister was in charge of the borders, and insisted that the transports of illegal Jews continue even as more bills were presented to UNRRA. But as trains of Jewish refugees rolled across Czechoslovakia, the costs continued to climb, with no reimbursements forthcoming. The fact that UNRRA received the bills did not mean all the bills were paid. UNRRA decided which bills to pay and the Czech government frequently received less than it spent.

In an interview with author Tad Szulc, Toman said, “Had a non–Jew occupied my post, he would have definitely stopped the trains and other expenses until payment was made.”[16] The fact that transportation costs and other expenses soared did not seem to bother Toman. As he said, as long as he was in power, Czechoslovakia would continue to provide transportation for the Jewish refugees.[17]

The British and American campaign indirectly exploited this state of affairs through press connections. Some Czech newspapers and radio programs began to discuss the fact that UNRRA was not paying for the refugees and the expenses were being shouldered by the Czech government that could ill afford them. These discussions received a tremendous boost when Mary Gibbons, deputy assistant director of UNRRA operations for Europe, arrived in Prague. On July 7, 1946, three days after the pogrom in Kielce, Poland, she publicly stated that UNRRA would not pay for Jewish Polish refugees who crossed Czechoslovakia, since they had already been repatriated to their homes following the war . She continued to repeat this statement throughout Czechoslovakia until July 14, 1946, when she left the country.

According to the JDC's Gaynor Jacobson, Gibbons repeated the same statements over and over, namely that the repatriated Jews of Poland from the Soviet Union had been repatriated at UNRRA cost, therefore there was no reason to pay for them to move again. This implied that the Jews were taking advantage of UNRRA. The fact that they were running for their lives did not matter to Gibbons. In every meeting with Czech ministers, high officials and the press she repeated that her organization would not pay for Jewish transients.[18]

The publicized statements by Mary Gibbons of UNRRA had one objective, to force Czechoslovakia to close its borders and not permit Jewish refugees to transit the country. Britain believed it had to stop the illegal ships with Jewish refugees that were embarrassing it throughout the world, especially in the United States. The photographs showing British soldiers manhandling Shoah survivors undermined world public confidence in Britain's ability to control and rule Palestine.

Gibbons was not concerned with UNRRA but rather with British foreign policy. The Czech press and many government officials saw one thing, Czechoslovakia would have to pay large amounts of money that it did not have. Czech cabinet ministers began to discuss the situation and a decision was made to close the border. The Czech and Polish governments closed the Czech–Polish borders[19].

The theme espoused by Gibbons and the British and American embassies was seized upon by the local press. The country was just starting to find some traction after years of Nazi occupation. The Czech economy was struggling, the government nearly bankrupt, and unemployment was high. The Czech people were opposed to the use of the little money they had going to help Jewish refugees.

The Kielce pogrom in Poland changed everything. Thousands of Jews began to move to the closed Czech–Polish borders. Confrontations between refugees and the authorities began. The General Secretary of the Czechoslovak Communist Party, Rudolf Slansky, visited the border and witnessed such a confrontation. Both governments were being strongly criticized for persecuting Jewish Shoah survivors. International Jewish organizations lodged protests in Czechoslovakia and Poland, accusing the countries of inhuman behavior. The free press showed photographs of the events. The Czech government met and discussed the situation. The foreign minister, Masaryk, led the fight for opening the borders. He was about to leave for New York to attend the U.N. General Assembly and try to get a loan for Czechoslovakia. He knew that opened borders would jeopardize his chances of getting the loan. The cabinet ordered the Czech borders opened to Jewish transients from Poland. Several specifications were added including the requirement that the transports must leave Czechoslovakia within 48 hours of arrival, and no transient would ever receive a permit to stay in Czechoslovakia.

The Polish government was also under heavy pressure to act following the pogrom, for its international standing was at its lowest point. The cabinet met and made a dramatic decision to let all Jews leave Poland illegally. The decision served two purposes: get rid of as many Jews as possible and in

|

|

doing so disarm the anti–government forces that kept insisting that Poland was controlled by Jews. The massive departing Jewish exodus would be proof that Poland was in Polish hands.

|

|

The Polish government ordered Marshal Marian Spychalski, the Polish deputy minister of defense, to conduct secret negotiations with Itzhak Zuckerman, one of the leaders of the 1943 Warsaw Ghetto uprising and currently an active member of the Central Committee of Polish Jews. The two worked out a secret agreement that was to commence on July 27, 1946, and end about February 1947, and would not be made public by either party. The agreement restricted emigration only to Jews, who also were forbidden to take gold, foreign currency or personal papers when they left Poland.

All travel arrangements were the responsibility of the Polish Brichah, which would also handle any and all other problems, including medical attention, food and clothing. Neither the Polish government nor any other Polish officials were to be involved in this modern exodus. Lastly, Marshal Spychalski verbally informed Zuckerman that the agreement only applied to the Polish–Czech borders.

While Zuckerman agreed to this last condition, he was distressed. The Brichah had long been making good use of the short but troublesome journey to the Polish–German border crossing at the port city of Szczecin (Stettin). The crossing point was troublesome due to Polish anti–Semitic attacks on Jews along the road and the Soviets manning checkpoints along this route. The Soviets frequently stopped and searched and sometimes arrested the Jewish refugees, handing them to the Polish authorities where they faced jail. Now the Polish government had told Zuckerman this shortcut was off limits. While Zuckerman understood the reasoning – the Poles wanted to keep the Jewish exit route a secret from both the Soviets and the British – he also knew the Soviets were aware that Jews were leaving Poland, although not the extraordinary numbers. The British would have been livid, knowing that many of the fleeing Jews would try to sneak through the blockade around Palestine. And the Poles had another reason not to upset the British. When the Polish government fled Warsaw in 1939 in the face of the Nazi invasion, they took Polish gold reserves with them, depositing them in British banks. And the gold reserves were still in London. Britain was in no hurry to return the gold and had used pretext after pretext to delay shipping the precious metal home. While the decision to let most of the Polish Jews leave was quickly turning into a matter of survival for the Polish government, the Poles had no intention of giving the British cause to keep Polish gold any longer than necessary. The Brichah agreed to funnel the massive exodus across the different borders points along the Polish–Czech border, notably the village of Nachod.

The Brichah was also determined to use the Szczecin (Stettin) crossing point whenever the need arose, regardless of the dangers.

|

|

In 1946 alone, the Brichah led nearly 24,000 Polish Jewish refugees across the Szczecin border point.[20]

The Brichah had another trick: it mingled Jewish refugees on trains carrying German citizens being deported from German areas that had been given to Poland at the Potsdam Conference held in Berlin from July 17 to August 2, 1945. These trains went from Poland directly into Germany. Once the trains stopped in Germany, the Jews were gathered up by Brichah guides and ushered to one of the DP camps in the American zone.

After the agreement with Marshal Spychalski was finalized, Zuckerman brought the document to the Central Committee of Polish Jews for approval. As usual, there was disagreement among the Jewish factions: the Communist and Bundist members vociferously objected to the terms. The Jewish Communists were steadily gaining strength in the Central Committee; their allies and the Bundists were also opposed to Jews leaving Poland despite all the real dangers that the Jews faced there. The Jewish Communists and Bundists were determined to build a socialist utopia even though this option or any option that called for remaining in Poland was rejected by most Jewish survivors. The Polish Jewish Communists continued objecting to Jewish emigration from Poland. They believed in a new socialist society where everyone would be equal, and argued that Jews should stay and help with the historic effort. While the actual number of Jewish communists was small, they were very vocal, influential and had the support of the Polish Communist Party. The Jewish faction of the committee took the matter all the way up to the Polish Central Committee of the Communist Party. Much to the dismay of these Jewish Communists, they were informed that the top officials of the Communist Party agreed with the terms struck between Spychalski and Zuckerman. After that the Jewish Communists raised no more objections.

The Bund had been one of the largest and best organized Jewish worker organizations in pre–war Poland. Marxist–Socialist in ideology, the Bund was anchored in a firm belief in a Yiddish–speaking cultural autonomy. Vehemently opposed to Zionism, the Bund demanded that Jews fight for their rights where they lived and continued to adhere to this view even after the war. But when the Spychalski–Zuckerman agreement was brought for a vote at the Central Committee of the Polish Jews, the Bund members were outvoted.

|

|

With the way cleared the question of funding became crucial. The Brichah appealed to the Polish branch of the JDC to finance the legal transport of thousands of Jews out of Poland. William Bein, the new head of the JDC office in Warsaw, assumed the office following the tragic death of Guzik in a plane accident. The JDC was already paying the Brichah's expenses to sneak Jews out of Poland. By the time of the Spychalski–Zuckerman agreement, thousands of Jews had already crossed the Czech–Polish borders, 5,000 in 1945 alone, and that number was dwarfed by the number of Jews crossing in 1946. Bein informed Joseph Schwartz, the JDC head in Paris, of the rapid increase in refugees illegally leaving Poland, now mostly across the Czech border.

Schwartz answered by sending massive shipments of food, clothing and medical supplies to transit camps in Czechoslovakia where the Polish Jewish refugees stopped briefly on their way to the DP camps in Germany and Austria. The reception camps along the Czech borders were enlarged and stocked with provisions for the Jews arriving from Poland.

|

|

Thousands of Polish Jews crossed the Polish–Czech borders at Klodzko, Walbrzych, Katowice, Krosno and Nowy Sacz. The Association of Polish Jewish Religious Communities actively encouraged Jews to leave Poland. Chief Jewish Chaplain of the Polish Army, Colonel Rabbi David Kahana, who was also the head of the Union of Rabbis in liberated Poland, urged all Polish rabbis to help the Polish Jews crossing the Polish–Czech borders.

|

|

The JDC offices in Czechoslovakia and in Poland were placed on a military footing to cope with the impending mass movements. The Brichah mobilized all its forces to deal with the transports. The Brichah staff in Czechoslovakia expanded to 150 people from a small staff of about two dozen people.[21]

Jews crossed the Polish–Czech borders prior to the agreement but the numbers were relatively small. In May 1946, 3,052 Polish Jews crossed illegally to Czechoslovakia, in June 1946, 8,000, in July 1946, 19,000. August 1946, 35,346 and in September 1946, 12,379 Jews crossed the border illegally.[22] During five months, 77,777 Polish Jews crossed the Czech –Polish border at a single place, Nachod. The camp was expanded and could handle up to 1,000 refugees for day or two. Of course, there were other crossing points in Czechoslovakia including Broumov where another temporary refugee camp existed. Both camps provided the refugees with a resting place, some food and some medical attention if needed prior to moving to the DP camps in Germany and Austria.

The Brichah and the JDC faced another serious problem, namely the Orthodox and the Hasidic Jews. Some of them had arrived with Brichah transports to Nachod or Broumov but then managed to travel to Prague. Others crossed the Polish–Czech borders with independent smugglers and reached Prague.[23] Their attire made them visible in Prague, which was off limits to Jewish refugees in transit because the Czech government did not want to publicize the transient activities. It also did not want to brazenly antagonize Britain and the United States. Many Orthodox Jews did not want to go to Palestine, and assumed that the JDC had visas for the United States. The JDC supported them but had no visas to distribute. The Czech government began to pressure the JDC to remove the Jews from Prague. The JDC and the Brichah did not want to antagonize the Czech authorities and began to encourage the Jews to leave Prague. The JDC social services officer in Prague, Florence Jacobson, the wife of Gaynor Jacobson, talked to these Jews and explained the situation. Various compromises were made that resulted in the departure of most religious transients. Some went to the DP camps while others went to Italy, France, and the United States.[24]

The mass exodus of Polish Jews rapidly started to decline in November 1946 when only 2,545 Jews crossed into Czechoslovakia, and 1,987 Jews crossed the border in December 1946.[25] In January 1947, 1,029 Jews crossed and in February 1947 only 1,700 Jews crossed the Czech borders. The Stettin crossing point was closed. Yet there were still Jews sitting in Poland with packed suitcases. Reports began to reach them that the DP camps were overcrowded and there were only limited possibilities available to reach Palestine or the United States. So they decided to sit and wait in Poland where security conditions began to improve. The Polish borders were closed at the end of February in accordance with the Spychalski– Zuckerman agreement. The January elections of 1947 gave the Polish government an absolute majority in parliament.[26] The government used all of its powers to crush the anti–government forces in the country. Public order was slowly re–established. The Jews felt a bit safer and hoped to be able to leave Poland directly without the need to smuggle themselves across borders.

The Brichah continued to organize transports of Jews from Poland and other areas and to send to Czechoslovakia. Most of the transports consisted of young people willing to endure hardship. During the entire year of 1947, only 9,315 Jews crossed the Czech–Polish borders.[27] Gone were the days of massive transports of Jews from Poland. The Brichah apparatus slowly decreased in size as did the JDC in Czechoslovakia. Both organizations played very important roles in transferring masses of Jews from Eastern Europe where they faced daily dangers to the DP camps in Germany and Austria. Both organizations worked together and established a force that would soon show its strength in the fight against Britain and in the establishment of the State of Israel.

The large number of people indicates the extensive operations of the Brichah in Poland.

| AMSTERDAM | Shimon | M |

| ARGOV | Lev | M |

| ASSA | Lea | F |

| ASSA | Aaron | M |

| BALTAN | Chaim | M |

| BEN HALOM | Rafi Fridel | M |

| BEN NATHAN | Asher Arthur | M |

| BEN ZVI | Isser | M |

| BRONSTEIN | Munia | M |

| BRONSTEIN | Paula | F |

| DAN | Yossef Freilichman | M |

| ELIASH | killed in action | M |

| FRANK | Ernest –E[hrai] | M |

| FRIDMAN | Yaacov Janek | M |

| FRIDMAN | Nati | M |

| FRIDMAN | Fredo | M |

| FUCHS | Miriam | F |

| GAFNI | Elchanan | M |

| GIBMAN | Moshe | M |

| GOTESMAN | Awraham | M |

| GOVSMAN | Moshe | M |

| GROSS | Moshev | M |

| HERBST | Itzhak Mimush | M |

| HIRSHBERTG | Heniek | M |

| HOOTER | Michael | M |

| JUCHT | Tzipora | F |

| JUCHT | Meir | M |

| KIHEN | Shlomo | M |

| KORN | Frida | F |

| LANDAU | Ze'ev Buba | M |

| LANDAU | Bubu | M |

| MARKUS | Yossef | M |

| MENACHEM | Sharon | M |

| NEUFELD | Akiva Noy | M |

| NEULANDER | Sylvia | F |

| NUSSENBLAT | Hannah Hanka | F |

| OFFER | Aaron | M |

| PEARLS | Yaacov | M |

| POSLANTZ | Yossef | M |

| PRINTZIG | Victor | M |

| RABINOWITZ | Zelig | M |

| RAJCHMAN | Alexander Shani | M |

| RAKOWER | Shalom | M |

| SELA | Itzhak | M |

| SHMULEVITCH | Tushia | F |

| SHTEINMAN | Jozek | M |

| SHTEINMAN | Moshe | M |

| SHWORDT | Leibush | M |

| WANG | Dorka | F |

| WANG | David | M |

| WEISS | Hella | F |

| ZISKIND | Shlomo | M |

Footnotes

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Brichah

Brichah

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2025 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 24 Mar 2017 by JH