|

|

|

[Page 321]

(Opsa, Belarus)

55°32' 26°50'

|

|

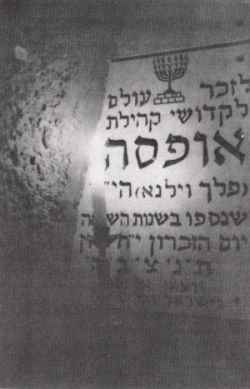

| Memorial stone for Opsa on Mt. Zion in Jerusalem |

Translated from the Hebrew by Laia Ben-Dov

Edited / Donated by Jeff Deitch

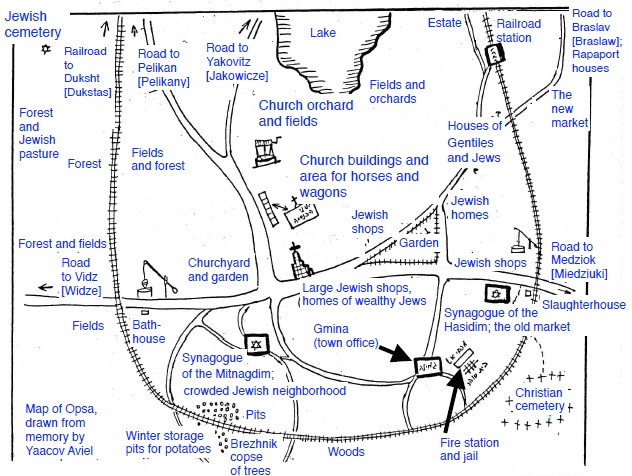

| [The map contains some inaccuracies, presumably due to a lapse of memory. For example, the railroad to Duksht actually ran out of Opsa to the west, not the north. The road to Pelikan went to the west of Opsa, not the north. The road to Vidz went to the southwest of Opsa, not the west. The road to Medziok went to the southeast of Opsa, not the east.] |

Translated from the Hebrew by Laia Ben-Dov

(Yiddish Translated by Aaron Krishtalka)

Footnotes Added / Donated by Jeff Deitch

|

I'll introduce myself.

I wasn't in Europe during the Holocaust, and in my birthplace I wasn't called Aviel.

I'm Yankel Abelevitz from Opsa [18 kilometers southwest of Braslav/Braslaw]. I lived in Opsa until I was 20 years old, and since 1938 I've lived in Israel. Not one member of my large family is alive, except for several cousins on my mother's side [the Rosenberg family]. Of them, the closest to me is Motke [Rosenberg], and it's in his words that I recorded his story of the Holocaust [on pages 339-351 of this memorial book; Motke is also mentioned on page 383].

At the end of the war, in 1945-46, I began to look for my family; I searched among the surviving refugees. I turned to the Jewish Agency's search office and the International Red Cross --- all in vain. They were among the millions who died; may their souls be bound up in the bond of eternal life. Later I thought how good it would be to create a memorial to my family and my town of Opsa, a remembrance of words and feelings for the good Jews I recalled so well --- and I began to write.

Once, in a cemetery [in Israel], alongside the memorials to our loved ones, I met a dear man, a kibbutz member, and he told me that he too was thinking of a written memorial. We joined forces.

All of my sections on Opsa are authentic, but of course from my point of view, sometimes with correct names and sometimes with borrowed names, but all is accurate and exact.

The sections on the Holocaust and the partisans are what I heard from meetings I had with survivors. My cousin Motke told me a lot, and I read and saw a lot on the screen. All were combined into a story [in the latter half of this account] and a poem [on page 465 of this memorial book].

As I said, this isn't the testimony of someone who was there; it was written by someone who wasn't there, based on what was told to me by those who were. The bodies of the millions are the real witnesses. Please accept my account as such.

The Time Tunnel

I enter a time tunnel and search for the past. I pace from beginning to end and try to break through the wall of memory, and I begin with my own account of my town. I burrow through my memories, calling up stories of childhood and youth. The dust of years covers it all, the town seems light years away. Does it still even exist!? Despite all my love of the past, I don't want to see you again. I'll describe you in words, in stories unformed by order, continuity or chronology.

[Page 324]

Closing my eyes, I see you in full: streets, people, markets, Gentiles, Jews, loves and arguments, gossip and celebrations, Sabbaths and weekdays mixed together, but everything is clearly seen. Here I see you spread between low hills, orderly and quiet on a Sabbath afternoon, noisy and bustling on weekdays and market days, the image changing with the day, vibrant and alive. I remember people by their names, nicknames both mocking and colorful and I --- one of them --- am standing to one side and recording . . .

Come, we'll take a short stroll through the streets:

We'll begin in the direction of Braslav [to the northeast]. Here you'll see a lot of sky and vegetation, with fields starting to turn green. The road moves ahead between two rows of trees with a thick canopy overhead: the main road to Braslav. Here's the estate of the family of Rapaport, a Jewish landowner with roots in the earth, whose livelihood comes from wagons. It's on his land that the local market, which operates each Monday, is located. The road's paved with cobblestones, and the wagons make a lot of noise on the way to the market. We descend the hill in the direction of the town, cross the railroad tracks and come face to face with the smithies of the Zilber family, Meir and his brother. In their small forge, sparks fly and hammers beat white-hot iron; horseshoes are nailed to the horses' hooves and iron hoops are put on wagon-wheels.

Here the road divides. We turn right and approach the railroad station. On the way, we pass the police station and several Jewish homes. At the railroad station, we see emotional meetings and departures. If you want to continue on, we arrive at a lovely corner --- a very pleasant place, deep in nature. My school was there.

We walk back and make our way to the town center. On the way we pass many houses, large and small, belonging to Gentile families, most of them farmers. This is where Shlomo the wagoner lived with his son Yoske, Yossel Todres and his son Moshe, and a few other Jews. The concentration of Jewish homes really began here, from the home of the shochet [ritual slaughterer], [Menachem-Mendel] Liberzon. Opposite lived the two Bikov brothers, Moshe and Gershon. Next door to the house of the shochet was the tea-room of Velvel [Levin] and his stout wife, Masha.

This is how the center looked after the [1928] fire:[1]

The Drisviatzki house, a two-story house built of red bricks, and next to it Abrasha Kagan, their son-in-law; both of them owned a manufaktura, in the language of the time [meaning shop or workshop, in Polish]. In front of them was the shop of the righteous and respected, thick-bearded Archik; opposite was Feivush the wagon-driver and next to him Leizer [Reznik] and his two daughters, Tania and Chasia. In the direction of the town center was the large house of the Levin family, a bakery and a guesthouse. On the corner stood an unfinished structure, just the foundations were laid and it belonged to the Gentile Kondatovitz [Kondatowycz]. He had an artificial leg and was the manager of the railroad station. To the left, in the direction of the village of Medziok [Miedziuki, about 1.5 kilometers southeast of Opsa], was the large shop of the Ulman family, a two-story house with a big courtyard; Ulman was the wealthy man of the town.

Beyond him was the house of the glazier, Chaim-Abba, a short man, “der kortzer Freitag” [“the short Friday”], with his sons and daughters. Next to him was the house of his neighbor and eternal opponent in argument, Reb[2] Chaim-Berl Bikov, the father of a dynasty of tailors. Next and on the same side came the bakery of Yisrael, who had a big nose: “Yisrael der noz.” After him was the home of Zelig the wagon-driver, Baruch-Itza [Medziukis] and his crippled daughters, some Gentile houses, a water well, and the synagogue of the Hasidic Jews, the largest in size, with the dignitaries and wealthy of the town. A steep, sandy path led to the Christian cemetery, pine trees whispered in the wind and, on winter nights, so people said, devils went there to dance.

[Page 325]

Some distance from there was the slaughterhouse of Leibel Munitz. A threatening dog, tied with a chain, frightened the children who brought the family chicken for slaughtering for the Sabbath. Behind the slaughterhouse were sandy hills that were crossed by the railroad tracks, forming a deep and formidable ridge. This was the edge of town on this side.

We return to the center. Here we see an unplanted garden in the shape of a triangle, encircled by a low wooden fence. Strong men could pull the planks out of the ground by hand. This was the center of town in the evenings, on the Sabbath and festivals; for gossiping, gambling, spreading rumors and arguing. Around the garden were scattered the shops belonging to the notables of the town; here was the house of Levin, the largest manufaktura of them all, owned by Reb Nachum [Levin] and his two homely, single daughters. People said of him that his intelligence was lacking. Next to him were the shops of Zalman Kaiatzki and others. Further along at the rise of the hill was the church, with its crosses glinting in the sun and its bells heard from a distance during festival prayers, funerals and other events. Behind the church was the priest's home, a house with many wings, a large yard and two big dogs. An orchard spread over the ground as far as the lakeshore. Two large, sturdy acacia trees stood upright, with storks nesting in them. Their cry announced the sunset and heralded the coming of spring. A garland of greenery encircled the lake, spotted here and there with estates and villages. If you wish to continue alongside the lake, you can reach the village of Pelikan [Pelikany, about four kilometers west of Opsa]. This is the end of Opsa on this side.

From the center we turn right, toward the road to Vidz [Widze, 22 kilometers southwest of Opsa]. We sit and rest for a few minutes on the bench outside our house, opposite the church. Now we go down the slope to the left, finding ourselves in the small alleys of the poor: low houses of wood, thatched roofs and impoverished Jews. In local slang, the place was called Srilovka. We pass the house of Leib the tailor, my mother's brother, and continue along the sandy alley and arrive at the synagogue of the Ashkenazim [the Mitnagdim]. We turn right in the direction of the pits, where the potatoes were stored in the ground in winter --- and again we've arrived at the Christian cemetery. We cross the railroad tracks with a jump, and we're passing through a birch grove called the Brezhnik, the lovers' thicket. What didn't people do there! But don't tell who was with whom!

Again we turn left and we reach the local authority building, the Gmina.[3] In the courtyard was the “Sunday” jail, where all the drunks were locked up [after a Saturday night's carousing]. Next to the jail was the fire station, a hall for the orchestra and a netball field.

We return to our house, on the road to Vidz. On the way down the slope stood an ancient acacia tree, completely hollowed out and good for hiding in during games, a water well on the right, the bathhouse and the home of the bath attendant, Reb Mendel. A small stream cut its way across the meadow, and further along the path a bridge was needed. Next to the bridge, a small pool had formed and frogs croaked there at night.

This is Opsa: brick houses in the center, miserable wooden houses in the poor neighborhoods, with smoking chimneys in the winter and the lowing of cattle in the summer. Green hills, a large forest on the horizon, and a blue lake connected to a chain of other lakes. Wagons hitched to tired horses, market days, Sabbath days and the ringing of bells, the Jews hurrying to prayer --- Hasidim and Mitnagdim.[4] Weddings and funerals, grooms and brides, poverty and scarcity, love and disputes --- this is Opsa.

In the winter, the town was clean, fresh and sleepy; bluish smoke rose up from the chimneys of the houses. It was cold outside,

[Page 326]

and cheeks were rosy. Inside the homes, the stove was hot with the cooking of the family meal. The snow lay thick on the ground, and a light wind sent millions of glistening snowflakes whirling. On moonlit nights young scamps would steal a sleigh and fill it with boys and girls. Kisses were exchanged, love blossomed, and people embraced and screamed as the sleigh went down the hill. Then everyone had to push it back up to the hilltop.

In the summer by the lake and on the hills of birch trees, there was talk and yearning for Palestine, as cultural clubs and Zionist groups argued among themselves.

We'll enter the houses again; we'll laugh together and perhaps even cry. Forgive me if I'm not so precise at times. Many years have passed since then --- many years . . .

Fire, Fire

Who doesn't recall the great fire of Opsa [in 1928]?! Everything was reckoned according to this event --- such and such happened before the great fire or, for example, “Do you remember this house before the fire?” and so on. The fire in Opsa was a milestone in the history of the town. That spring Sabbath morning brought calamity. A spark from the dirty chimney of a farmer on the road to Medziok flew into the air and landed on the straw roof of his neighbor, Baruch-Itza. The straw ignited, and the fire destroyed most of the houses in the town.

As is written, there are four causes of damages whose harm is severe --- and fire is one of them.[5]

That same Sabbath morning, the members of the Hasidic synagogue were taking a leisurely stroll; they'd just finished the morning prayers and were on their way home. The synagogues in town had divided Opsa in two: the Hasidim and the Mitnagdim, one against the other. The Hasidim considered themselves the more honorable, the wealthy class. The Mitnagdim were the simple folk, residents of the neighborhood of Srilovka, and they were wagoners, small traders, owners of small shops, shoemakers, tailors, and middlemen of various kinds and the like. There was a barrier between the two groups, even hatred; one side called the other “Hasidishe kishke” [“Hasidic tripe”] and was answered in kind with disparaging words. And when there was a potential marriage between the two groups, the issue became very serious. The Hasidim always extended the length of their prayers, and by the time these had finished the Mitnagdim were already halfway through their Sabbath cholent.[6]

And so it was on the Sabbath of the catastrophe: The Mitnagdim were already sitting at home eating, while the Hasidim had just begun to leave the synagogue.

I remember this Sabbath as if it were yesterday; I can see clearly pillars of thick, black balls of smoke billowing up through the sloping roof --- and the house was the home of Baruch-Itza.

The people from the Hasidic synagogue stopped walking, they didn't understand what was happening --- was it really a fire?

At that moment, the flames burst out and tongues of fire engulfed the roof and house, spreading wildly from every corner. The spring breeze blew the flames this way and that. The house was soon a mass of flames. In fear and despair, the men from the

[Page 327]

Hasidic synagogue began shouting “Fire! Fire!”

“There are four causes of damages whose harm is severe --- and fire is one of them.” On summer days, a fire could destroy an entire village, down to the foundation. One spark falling on a thatched roof, and the entire village became the fuel --- houses, barns, trees --- nothing would remain.

Communities prepared for catastrophes of this sort. In every town was a fire brigade. In Opsa too there was a fire brigade, located behind the Gmina. There were water-wagons on two wheels, some of them full and some empty, with hoses of fabric and a pump for a crew. To get the water-wagons to the scene of the fire, horses were required. When a fire broke out, our firemen would go into the street and stop any farmers with horses and wagons, take the horses and hitch them to the water-wagon, and gallop quickly to the site of the blaze. The farmers knew that their horses couldn't go very fast, and they objected. This was an opportunity for our firemen to show their speed and determination. In most places, the firemen were young Jewish men.

When a crisis or catastrophe occurred, the church bells would start ringing incessantly. In normal weekday circumstances, as I said, the emergency services would've been ready. But this time it was Jewish homes that were being consumed, and it was the Sabbath and a mealtime --- the men were confused and unprepared.

It was said that one of the men from the synagogue started shouting “Fire!” with his kapote[7] fluttering in the wind, and before the church bells started ringing he'd managed to cross the entire town, shouting all the while. The fire spread quickly, igniting every roof, jumping from house to house. Within moments, many houses were ablaze and the town was filled with smoke and the sound of explosions.

The bells rang and rang. Thick smoke covered the sky and people were running around panic-stricken, shouting, pushing wagons filled with belongings and goods, bedding, and other items. No one dared to combat the fire. They only wanted to save as much as they could --- and quickly.

The ringing of the bells was understood by the villagers [outside Opsa]. They came in crowds, some to help and some to loot, but most of them to loot. Bolts of floral-patterned fabric rolled around in the streets, but no one collected them. They rolled loosely among the wheels of the wagons and caught fire. Woe to the eyes, what wealth was rolling around under people's feet! Expensive fabrics that they couldn't afford to buy were rolling in the streets, all they had to do was pick them up and run. And then came the stream of villagers. They came with empty sacks, with wagons waiting outside the town; they filled their sacks and fled through the fields. Even the honorable ones among them were tempted to follow the mob; they looted, emptied their carts and sacks, and returned again and again.

The blaze ran wild; house after house became a fiery torch. My mother held me next to her, and I could see she was hesitating: to start packing the bedclothes, or wait for a miracle. Our house stood at the edge of town, far from the fire's center.

Suddenly my three brothers arrived --- all firemen --- followed by my father; they all began to pack up everything they could. First, my mother spread sheets on the floor and piled up all the bedding, pillows and moveable items. She quickly emptied the cupboards, piled up and tied everything, and my brothers loaded the packages onto the wagon and left town at a gallop.

We were flax traders and had a storehouse full of parcels and piles of flax, both processed and raw. Everything was piled onto wagons and moved out of town.

I was appointed to guard over the piled-up belongings while my father and brothers took away everything that could be moved.

[Page 328]

From the top of the hill, I looked upon the appalling sight of the burning town, at its center the church --- for the church was already engulfed in flames. The entire area, buildings, cowsheds, trees, crosses, everything was wrapped in flames --- and the bells continued to peal out their warning. What wasn't burning? The stained-glass windows with their pictures of saints exploded from the heat; shards of glass flew in all directions, crosses collapsed and torches flamed everywhere.

Suddenly, the bells fell silent. The fire had reached the tall central bell tower. Hundreds of farmers with their sacks of loot froze in place at the sight of the burning crosses; they bent their knees and crossed themselves with shaking hands, crying, “Jesus and Mary, in the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost, what are we seeing? Oh Mary! What a sight, what a sight!” The Jews also stopped for a moment and wondered, “Will the bell tower fall, or not?!” The tall steeple reared up high into the sky.

People stopped and stared. “Oh Jesus! Mary!” The bells began to fall one by one with loud crashes, making a terrible sound. For a moment all was silent, and the believers held their collective breath and knelt on the ground. The bell tower began to lean to one side. The fire continued to eat away at it. A terrible cry burst from the crowd, they covered their faces in order not to see, and a second later the tower collapsed in flames, in a cloud of fire and smoke. “Woe to the eyes, Jesus, Mary, the end of the world.”

All night long, I couldn't sleep. The stars twinkled at me all night, and I was cold. The wind brought clouds of smoke, and tears streamed from my eyes. I sneezed endlessly. The whole town was a mound of flickering embers, and sparks floated here and there and flew up to the heavens.

I awoke at dawn, cold and thirsty, to the sound of birds chirping. My mother was sitting next to me, and she told me that our house was undamaged and my father was there guarding it, to make sure that nothing would be stolen. My brothers were busy driving away the Gentiles and guarding the remaining shops. Later on, wagons began to arrive from Vidz. Our uncles came with bread, milk and candies for me, kissed me on the forehead and disappeared into the remnants of the town.

|

|

| The Opsa fire brigade |

[Page 329]

Mendel the Bath Attendant

Do you remember Mendel? You know --- Mendel der bader (bath attendant). If you're from Opsa, you certainly knew him. There were many types of Jews in Opsa, varied and eccentric, wealthy and beggars, those who were satisfied and those whose Sabbath meal was given them in secret by devout ladies who left a basket of food at the entrance of the house before slipping away.

My heart goes out to them, the poor and needy ones, making do with little, lowering their head and mumbling their thanks: “Gam zu l'tovah” [“This too is for good”]. Good Jews, making the blessing over a dry slice of bread and refusing all help with a smile. Good Jews, rising early for the morning prayers, sitting quietly in a corner of the synagogue. When they were called to read the Torah, their aliyah was “thin” and the blessings they spoke could barely be heard. The weekdays were for toil and labor, Sabbath afternoon was for sleeping, and the time between the afternoon and evening prayers was for reading from the Book of Psalms.

Special, different Jews. In the winter, they wore sheepskin hats and faded fur coats, rubbing smelly resin oil on their boots for protection, or wrapping the boots in rags . . . all winter long they kept warm by the stove, and their main food was potatoes, prepared 10 different ways. On market days they sought their livelihood among the Gentiles, and on holidays they looked like wealthy men, going to the synagogue dressed in holiday finery, some to gossip and some to pray. They danced at weddings, drank vodka and burst into song: “When the Messiah comes, what'll we eat --- when the Messiah comes, what'll we drink?” And all the replies were heard only in song.

The women were busy at home, cooking and baking bread; pregnancy followed pregnancy, and then they looked after the children --- many children. A sweater made of coarse wool covered half of a woman's body, including the head, and a sigh accompanied every story or piece of gossip.

There were many people like these in Opsa. One of them was Mendel the bath attendant. There were a few “Mendels” in Opsa, each one with his own occupation and status. This Mendel was the stoker and operated the public bathhouse, which was used mostly for ritual bathing by the members of the Ashkenazi synagogue [the Mitnagdim] and Jews whose homes were nearby.

Mendel served the men and his wife, Yenta, the women. The bathhouse was located on the bank of a stream that crossed the road to Vidz; a creaking wooden bridge passed over the stream. The water next to the bridge formed a large pool covered entirely by plants. Frogs croaked in the pool all summer long, providing an evening melody.

The bathhouse was built of wooden beams, very low and covered with a roof of straw that had turned green with age. The windows were small and the door was low, to prevent the escape of heat. Bathhouses were only built on the shore of a stream or a lake --- who could carry for long distances the huge amounts of water that were needed?

Every Thursday of every week, Mendel would rise before dawn and start to carry buckets of water from the stream: Thursdays for men and Fridays for women. It wasn't easy; he had to fill two gigantic wooden barrels with water, fill the ritual bath, and bring and prepare wood to heat the water. This was Mendel's hardest day.

A massive stove sat in the middle of the bathing room, and low benches lined the walls. The fire heated rounded stones, arranged inside the stove, to an intense heat. Mendel would take the heated stones

[Page 330]

and throw them into the water barrels until the water was almost boiling. Some of the stones he threw in the mikvah [ritual bath], so that the water there would be warm. The floor of the bathing room had coarse grooves for the water to drain out, first to the outside and then to the pool next to the bridge. On one side of the bathing room was a raised platform, with stairs up to the ceiling; it was called a pol [“floor” in Polish, here meaning a raised platform]. This place, where the lashings in steam were done, showed the quality of the bathhouse.

From the side of the entrance and behind the stove, steps led down to the mikvah. A narrow, dark corridor at the entrance, wooden benches for removing boots, nails in the walls for hanging clothes, and a few sparsely scattered sacks underfoot --- this was the entire bathhouse.

Let's go back inside and see what Mendel does on Thursday, his difficult day.

Before dawn, he's already on his feet. In winter, the cold outside penetrates the bones --- you should know that most of his clients come on winter days, because in the summer they can go to the lake outside and bathing there costs nothing. Mendel has a sheepskin coat; it's faded and full of oil stains, but this peltz [thick coat of fur or sheepskin] is long and covers about three-quarters of his body, leaving his legs free. When Mendel puts on his coat, his soul is happy; he takes the rope that is always in his pocket, passes it twice around his hips, tightens it firmly and then he's ready. He just has to take the food Yenta prepared for him --- and he's on his way.

Mendel arrives at the bathhouse, takes the buckets and begins to fill the huge barrels. His fingers are bent like hooks, hardened and callused from the heavy loads he's carried for years. When he's finished filling the barrels about halfway, he lights the stove. The wood has already been arranged carefully so that air can penetrate between the stacks and it'll burn with a nice flame. There are thick branches of birch trees and a few thin branches, so that the fire can catch hold quickly. Mendel sees that the fire's going well, so he takes a break. Sitting opposite the fire, he begins to doze --- but G-d forbid he should fall asleep. He has to get up immediately and continue. There are still many more buckets of water to bring to the barrels, and the mikvah too needs to be prepared. By the time he finishes filling the water, the sun's already high above the treetops; daylight penetrates the bathhouse, the cold abates and it's possible to take off the peltz. He says a short prayer without his tallit [prayer shawl] or tefillin [phylacteries]. He places a low stool opposite the fire; first he makes a blessing and then he takes a bite of the bread and food that Yenta has cooked. He's opposite the fire and it's good for him here, but his eyes are closing and there's still a long time to wait until the bath is ready.

Bathing begins only in the afternoon. Mendel finishes eating and sees that the fire's hot and well arranged. The stones aren't yet hot enough. Mendel lies on the warm floor and dozes off.

There are some days when he wants to go home to snatch a longer sleep --- that would be very good, but it's also dangerous because there's a risk of the bathhouse catching fire, Heaven forbid. A tiny spark is all it takes, when the stove's very hot and the entire structure's built of dry wood . . . Such a catastrophe doesn't bear thinking about. Oy! Oy! He knows of several bathhouses that went up in flames. Heaven forbid!

The sun's now hanging in the center of the sky, and everything seems secure; Mendel goes home for a few hours of good sleep. Mendel lived in a side room attached to the house of my grandfather Mottel and my uncle Leib. My grandfather was known during his life and afterward as very welcoming to guests, and he took Mendel under his roof. The house stood on the lower part of the road to Vidz. It consisted wholly of additions, patches and attachments of walls to walls, under one large roof

[Page 331]

of straw that was green with age. The windows were low and the panes were broken and covered with newspaper; the doors creaked, and a narrow pathway led to the entrance. Mendel's “apartment” consisted of one room that contained a kitchen, a wide bed, a table made of coarse wood and two stools on either side. Mendel also had an “inventory” of livestock --- a big, wild she-goat with large horns and a constant appetite. She was tied with a short rope in the corner of the passageway, with just enough room to allow access to the doors leading to my grandfather Mottel's door and to Mendel's door . . . close by was a ladder leaning against the wall, with a top that reached the attic, where hay for the goat was stored.

There were a couple of reasons for keeping this animal. First of all, she gave milk and that was good for the health, there was nothing better for babies when they had a cough. People would buy milk from Yenta by the cup, paying more than for cows' milk. Second, the goat kept bothersome people from coming to the door and asking, “So, Reb Mendel, can you come to the bathhouse already?” They had to repeat their request a number of times, because Mendel was sleepy and didn't hear well. He'd wake and ask, “Whose are you?” because he didn't know all of the town's young scamps, and the answer was usually “I'm the son of so and so, who's the son of so and so.” Mendel's reply was usually based on the fact that he knew who among the people paid generously and who gave only a few small coins. Once someone was seen going to the bathhouse, other people would follow and then it was impossible to refuse them all. Those who came first had the advantage --- why? They had no competition, you could get undressed and there were nails available on which to hang your clothes. You could hum music or sing songs, no one bothered you, and there was plenty of hot water and pails available. And most important, the place was warmed from all the hot steam and there were brooms on the pol.

The job of the goat was to scare the children and keep them from coming to Mendel's house: Beware, anyone who dared to approach this wild animal. There were no such adventurers and if anyone dared to try, they were sure to receive a good butt in the behind and a tear in their trousers.

Looking back from a great distance in time and space, I sense how woebegone the place was, how hard it was to make a living, and how impoverished life was. But it was good in our eyes, and we looked to escapades and pleasures, because laughing was healthy and there was nothing better for the body than a steam-bath. And who didn't want to be among the first? The steam rose up like incense with each spray of water on the hot stones, and you could lie on the pol, hit all parts of your body with the broom, and encourage yourself by singing prayers. You came early --- no one took your soap, your towel didn't “disappear” or other such pleasantries . . .

Mendel was quick-tempered and disliked those were privileged. For him it was a waste of hot water and steam, and he didn't want first-comers. But how could I refuse my father, who said to me, “Nu, Yankeleh, gib a shprung tsu Mendlen --- nor freg im! Nu, shoin?” [“So, Yankeleh, hop over to Mendel's --- just ask him! So, get going.”] So Reb Mendel loosened the rope tied to the goat, and our Yankeleh received a good butt on the backside (it shouldn't happen to us!) and returned home crying. On the Sabbath, coming out of the synagogue, my father, of blessed memory, whispered in Mendel's ear, “Did you know your goat attacked my Yankeleh and ruined his trousers?” Mendel replied, “And did I tell him to come to my house? What's this? Am I doing a circumcision or distributing cakes?”

I swore to avenge my disgrace. I took some children with me to help, and away we went. The first thing we had to do was anger the goat so that she'd be ready to attack all comers. Then one of the gang climbed

[Page 332]

into the attic through a hole in the roof, and from there descended the ladder to the rope-end tied to the goat, to release her. Quietly we went out and then all of us banged on the window in panic shouting, “Mendel, the bathhouse is on fire, it's burning, burning, burning!” We hid behind the fence and yelled, “Great G-d! The bathhouse is burning and he's asleep here in the house and not guarding it! Good Jews, help! Help!” With one hand Mendel grabbed his coat, and with the other he buttoned up his trousers and rushed into the passage --- straight onto the horns of the maddened goat. Oh, what a zetz [whack] he got; it should happen to all haters of Israel. And behold --- the bathhouse stood unharmed in its entirety, with just a small wisp of smoke curling up from its chimney; all was in order. Now the children burst into laughter and began to run --- with Mendel after them, chasing and cursing, throwing sticks and whatever came to hand; may his curses fall on the heads of all the Gentiles, pfui [ugh], all the unclean scoundrels, and may their names be erased from history!

On Fridays, the ladies' day, Yenta guarded the entrance. She sat on a stool, wrapped in a coarse headdress, with a downcast look so that so no one would say an evil eye had harmed a pious woman who'd gone to the mikvah. Modesty became those who went to the mikvah. Yenta sat there with coins in her lap, not even knowing who went past her.

What did Mendel do on the other four days of the week? People said he slept, warmed himself next to the stove, prepared wood for heating, and recited Psalms in the synagogue.

On the Sabbath, he rested. He rubbed his boots with resin oil, put on his “four corners” [tallit katan or small tallit, a four-cornered undergarment with ritual fringes attached to the corners] and his kapote, and sat inside the synagogue near the exit. Just once a year, he was called to the Torah --- on the holiday of Simchat Torah.[8] Then the sexton would call out, “Stand up, Reb Menachem-Mendel.”

I've No Photograph of My Father

I invited an artist to come, and I said to him: “Take your brushes and paint, and make for me a portrait of my father.”

“Where's your father?” asked the artist. I replied, “He went to heaven in the smoke of the crematoria. I'll describe him to you in words, while you use your brush.”

And this is what I said: “Draw me a Jew about 60 years old, a father and grandfather; I haven't decided yet if he'll wear a yarmulke [skullcap] or a black, peaked cap. Draw a beard for him, not too long, spreading a little to the sides, brown with a sprinkling of gray hairs. If there's a yarmulke, then emphasize the large, bald forehead. Draw him with payot [sidelocks] turning gray, his hair at the back cut short.

“Give him a thin nose, a little long with a slight hump. A typical Jewish nose. Draw warm brown eyes with small lashes; they too had some gray hairs. Show him seated and give him a confident gaze, one that inspires belief in the observer and confidence in the listener. Give him a bit of worry in the corners of his eyes, but not fear; give his eyes an expression of comfort and ease with other people, and an understanding of the soul.

“Now draw a mustache that merges with the beard and completes it. Draw him in his holiday attire, in a white shirt without a necktie and with a surdus [long coat] open at the back to the hips. The coat is gray, not black, because black was the color of the Hasidim and he belonged to the Mitnagdim. His trousers are black, with the bottoms tucked inside the boots. The boots were originally brown, but they've been oiled with resin to keep out water and dampness in winter, so their color has darkened. Scatter patches of brown and black here and there. I'll wait until you finish, and then we'll continue.

[Page 333]

“Now we'll fill in the background.

“Behind him a sandy pathway leads to the synagogue, and on the sides are low, wooden houses with straw roofs and low entrances, a high threshold and small windows. Artist, please put piles of firewood against the wall. Draw a yard with a stable in it, with the head of a cow or a horse peeking out. Add a little green to the roof, some moss that's grown here and there --- but not too much! No, there are no goats on the roof.

“Drink your coffee, keep listening, and we'll continue.

“I want a few more touches of your brush on the beard. You know, the beard isn't just an emblem of Judaism, it's also a symbol of status.”

A survivor told me that my father had [later] cut off his beard so that he could cross from one ghetto to another after becoming separated from my mother.[9] This enabled him to move freely without harassment, you understand, but what mental torture he suffered because of it, what humiliation.

“What did you say? No, Heaven forbid! Don't paint him without the beard or with protruding cheekbones, a humiliated look, ashamed and downcast eyes. No! Not bowed down, not fearful, not weak. Finish up the portrait with balanced colors and a relaxed figure, a forgiving smile and a calm mood --- this is how I see my father.”

The Cursed Beet (My Father's Death)

The smell in the freight car was unbearable. People vomited from lack of air, and the vomit added to the stench. It was terribly overcrowded. People were lying next to each other, their bodies touching.

Curled up, they lay in disorder. They couldn't change places or move, lest someone grab the space left empty. They couldn't remember exactly when they'd been loaded onto these freight cars on the way to “work,” to toil in factories or on the roads, so they'd been told.

It was already the third day of the journey. At night, it was cold. The packed-together bodies gave off warmth. At first, people complained and quarreled over every centimeter, over parcels of ownerless clothing and muddy shoes, and some were hit in the face unintentionally over a scrap of onion or a cigarette butt.

The women screamed, the men hushed them. At night sleep overtook them, they organized into groups, spoke or remained silent --- Jews imprisoned in freight cars, on the way to an unknown destination.

They stopped briefly at a station on the way. In an unknown country, with a language little understood. Running terrified, some to relieve themselves behind the trees, some to get a hot cup of tea and buy a morsel of food, some to pray, and some to exchange a glance with a relative from another freight car.

At the station, farmers waited for the trains: to buy and sell gold for bread, watches for onions, jewelry for flour, shoes for an egg. They bought and traded quickly, pressed by time and the threats of the accompanying soldiers.

On the third day of the journey, stations along the line had an additional job. The dead had to be taken out of the freight cars and laid at the side of the tracks or under the trees. There was no time for a ritual burial. The dead were covered quickly with earth, and the Kaddish was recited in the freight cars.

My father was in one of the freight cars.

[Page 334]

Something came to him in a strange way: the melodies of Yom Kippur [the Day of Atonement]. Indeed, he was quite used to them when standing before the Holy Ark in the synagogue of the town. The melodies, the musical flourishes, the words came to him --- but why suddenly Yom Kippur?! True, he'd eaten nothing for two days. He wasn't hungry, just weak. He bent over a little, leaning against the side of the freight car and --- as is fitting when serving the Holy One, blessed be He --- he covered his face with his hands and sang in a whisper:

“All vows, personal oaths, pledges and undertakings . . .”[10]

What a sacred melody, and it comes from the heart.

“Vows shall not be considered vows, and pledges not pledges . . .”

What did I promise and not fulfill? What do I owe, and to whom? Only to Thee, O Lord. True, he thought, I lied to the German soldiers. Three times he repeated, “All vows . . .” repeated and recited.

He buried his face in his hands and lowered his head within the collar of his coat. What shame! How will I stand before the Holy Ark with a trimmed beard?[11] What villain had taken hold of his beard with one hand and scissors in the other, cut and pulled, and now he looks like a laughingstock, the pain lasted many days and the embarrassment still hasn't left him. On the third day of the journey, he went out into the station huddled in his coat, bent over, hurrying --- what could he buy, what could he pay with? In his pockets, nothing remained. He stood before the farmer, measuring him with a look, spreading his arms to the side as if to say, “I've got nothing,” pointing to the bread in the other's hand --- I've got nothing to give you for it.

The farmer's eyes fell on the ring on my father's hand, and the farmer touched his hand and helped my father to remove it. Then the bargaining began --- a full loaf of bread for the ring --- or half a loaf and a beet. The beet looked good, fresh, with damp earth still clinging to it. Ah --- of course, a beet. When we reach our destination, we can cook some good soup, borscht, there's nothing better than hot borscht.

For a moment, he thought he'd bargained well. But without the wedding ring on his finger, he felt naked. His maddened thoughts began to turn toward his wife. The children --- where were they all? Oh, Lord of mercy and forgiveness, pardon this foolish deal. Now he'd have to hide his hand. How foolish it had been to take off the ring.

He shoved the beet in among his belongings and began nibbling at the bread. Again the music of Yom Kippur came to him. The tragic story of the 10 Martyrs,[12] of those forced into conversion and martyrdom. He knew most of the Yom Kippur prayers by heart.

With a screeching of brakes and the banging of freight car into freight car, the train came to a halt. Evening was already approaching. Who knew what time it was? All the watches had been sold long ago to pay for bread. In a flash, with an ear-splitting screech, the doors were flung open. Soldiers standing before them began to hurry people out of the freight cars --- “Forward! Forward! Schnell! Schnell!” [“Quickly! Quickly!”]

Pushed by a wave of people, pushed and pushing.

What's the hurry? What awaits us at the end of this road? People see buildings, chimneys, surely a factory, and think let's get there already, so we can rest a bit.

He was pushed, and his parcel of clothes fell from his hand, along with the beet.

“Oy, oy, oy, the hot borscht, the soup . . .”

He bent down to pick it up but missed and knelt on his knees, his hand in the mud.

The melodies of the Yom Kippur prayers didn't leave him for a minute . . .

--- “But we bow . . .”[13]

[Page 335]

The cursed beet, after hitting a foot it rolled away . . .

He was kicked and pushed, he fell flat on the ground . . .

“. . . in worship . . .”

His face touched the muddy earth.

“. . . and thank. . .”

He was stepped on. His face sank into the mud.

“. . . the Supreme King of Kings . . .”

They rolled him to the side of the road. His face to the sky --- he saw a great, blinding light. He looked . . .

“. . . the Holy One, blessed be He . . .”

He breathed no more.[14]

Partisans

Go there, they told me, in the Kozian forest [stretching south and east of Opsa] you'll find partisans from your area --- but be careful!

I slipped away, and after walking all morning I found myself a hiding-place and waited for night to fall.[15] Before it was dark, I got up and left my hiding-place and began to approach the edges of the forest. The smell of cooking reached me, and my appetite awoke at full strength. I hastened my steps until I was almost running. Ahead of me at the horizon of the forest, I could see a pale blue wisp of smoke rising against the dark sky. I saw a flickering dim light coming from the silhouette of a house --- I made my way there.

With caution, I began to approach the house. I circled around it and moved closer, circled it again and approached the lighted window. With hesitation and great fear, I knocked three times. There was no response, no sign of life. I knocked again. Suddenly a face appeared in the window pane; the face of a woman --- or was it an evil spirit? Her hair was wild, partly covering her face, partly covering her naked breasts --- she pressed her nose against the glass and took a long look at me; I couldn't take my eyes off her face. Suddenly she screamed, “Pavlo, is it you?” [Then, in Polish] “In the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost.” She touched her hand, her forehead, her chin and shoulders and then disappeared inside.

A few fearful moments passed like a lifetime, it seemed to me I waited there for hours --- until I heard a door creak on its hinges. There in front of me stood Yoske [Shneider] from Opsa. I recognized him immediately. His small black beard framed his pale face, his eyes burned from his black brows, he was slightly stooped and had prominent cheekbones, with eyes piercing like knives and a German rifle on his shoulder. “Du bist Itzke?” [“Are you Itzke?”]. He held the door with his free hand. I approached him, and we went inside.

A soft, murky light fell on the walls of the room. The dim light from the kerosene lamp created long shadows. This was the house of poor farmers, made of rough-hewn logs and a floor of pressed earth. A sharp odor of urine rose from the floor, with the smell of sweaty feet. It was one large room with a long table in the center and wooden benches around it. On one side stood two wooden beds, with coats and sheepskins thrown on them. In the far corner stood a huge stove, and from the darkened corner I heard a faint rustling and the murmuring voice of the woman from the window, who

[Page 336]

continued to call, “Pavlo, is that you?”

Yoske sat me at the table and called to two other people, who came out of the shadows. They presented themselves: Chaim from Kozian [Koziany, 28 kilometers south of Opsa] and Moshke from Postav [Postawy, 22 kilometers south of Koziany]. While I told them about the hardships of my journey and the ghetto, Yoske gave me a bowl of potato soup and a quarter-loaf of bread. We sat for more than an hour in conversation that went on into the night. The other two went out to sleep in the stable; Yoske and I remained. The fire in the stove went out, but the coals continued to whisper.

“You must be wondering who the woman is and why she called you Pavlo?” I didn't know Yoske Shneider, the son of Hertzel the shoemaker, all that well. His father had been a courageous man. I heard the father had been badly tortured by the Gentiles of Opsa at the beginning of the war and they'd killed him. Yoske, his only son, a strong-fisted man, was quick as a knife and bitter in his soul; he'd fled to the partisans. Here in the forest, I'd found him. He spoke quietly in a deep voice, spoke and stopped, playing with the German bayonet in his hand. “We've been in this area since the spring, sometimes in this house, sometimes in the forests and the swamps. Our contact with the rest of the partisans is occasional and only when Jews are there.”

“I'll tell you about the woman,” he said. “Pavlo was her husband. They had a son as well, about 15 or 16 years old. One day the boy went to the market and never returned. It happened before we arrived here. Pavlo went looking for him for an entire week, but returned on foot without his son or the horse and wagon. After that, he'd get up every morning and wander around the field or next to the road. Early one morning, we heard a deafening noise in the distance. We understood immediately that German tanks were approaching. We rushed into the forest, and from the dense undergrowth we witnessed a shocking sight. Three tanks approached, one in the middle and one on either side. They were moving slowly, keeping a lookout, stopping for a moment and then advancing. They left deep black furrows in the ground like a plow, throwing clods of fresh earth to either side; trees were bent over and never straightened --- they continued toward the house.

“Pavlo was in the cabbage patch, gathering the heads into a pile. It was the end of summer, and the colorful heads of cabbage stood out against the black earth. The tanks continued toward the cabbage patch, straight toward the place where Pavlo was working. He saw the threat and began running toward the tanks, waving his hands and shouting, 'Please, have pity, turn aside --- they're all I have.'

“The tanks continued straight toward him. At a distance of just a few meters, from the turret of the leading tank appeared a German soldier with a pistol. He fired a shot that was barely heard, and Pavlo fell face down in the muddy earth between the rows of cabbages. Our breathing stopped. The soldier who shot him waved his hand and disappeared inside his tank, and we saw how the tank alongside it drove over Pavlo's body and the rows of cabbage. We've seen so many horrors, Itzke, believe me --- our hearts are made of stone. The others wanted to attack the tanks with bottles of kerosene that they had, but I stopped them. The entire spectacle took just a few minutes. The tank rolled over Pavlo's body and plowed two furrows in the cabbage patch. Body parts and blood were mixed into the muddy earth: here a hand, there a leg, his head. Clods of earth glistened with blood --- the tanks just kept moving.

“Six furrows remained in the field, and parts of Pavlo's body were scattered in two of them. I told you I'd seen horrors. We came running up, and we began to vomit and cry out. When she heard us, the woman came out of the house. She approached the cabbage patch, not knowing what had happened. She got a little nearer and found herself standing next to Pavlo's severed head.

[Page 337]

“After that, she lost her mind. Now she calls everyone Pavlo. The partisans come to the house and they lie with her without shame --- to her deranged mind, everyone's Pavlo.”

A Meeting

While the smoke of the crematoria in Europe was abundant with the smell of burning flesh, I was in the blue uniform of His Majesty's Forces.

The renowned German commander [Rommel] got as far as the gates of the land of the Nile. On the edge of the desert, the Allied army blocked him, pitting steel against steel and man against man. The headquarters of my unit --- the Middle East Command --- was moved out of striking distance, deep into the heart of Africa, to central Kenya. Later, witnesses to the horrors that had taken place in Europe began to arrive. Trains of Polish refugees began to pass through to the location of their settlement in Africa [sic].

Searching for my family, I found myself in a refugee camp --- who had seen anything, who had heard? Opsa, Vidz, Braslav --- it was Jews I was searching for, Jews. The refugees were old before their time, some were mentally unbalanced, some were missing limbs. The women cooked sweet potatoes on burners of stones in the blazing sun. Inside, in the cabins, the men were lying down, remnants of men.

Suddenly, I heard [in Polish], “Isn't that young Abelevitz?” I answered, “May the great Name of the Creator of the universe be magnified and sanctified.” The man gaped at me: “Don't you recognize me? I was your teacher. Sit here. I know what you're looking for --- but you won't find it.” Sunk in thought, he paused and said: “It's a world that's been destroyed --- but I'll tell you.”

“The Germans retreated and the Red Army broke through, determined to be the first to reach Berlin. The Oder River, with a bridge across it, was the Germans' last line of fortification. It was necessary to cross the river and prevent the Germans from blowing up the bridge. A suicide mission. The forward Russian command called for volunteers and hundreds of Jewish men volunteered, many of them from our area --- Opsa, yes, Vidz --- maybe your brothers as well.” He paused, looked at me and rolled a cigarette. He lit it, drew on it, and continued: “It was war!” [said in Polish]. “What a massacre! The commander, a real hero, tall and straight, gathered them together before dawn. Nu, Yidn, lomir geyn! Shema Yisroel! [Come on, Jews, let's go! Hear, O Israel!].

“The night wrapped the river in deep darkness. On the other side were the Germans, dug in and armed. Above our heads the Russian artillery began to rain down a ferocious bombardment. They really gave it to them, the sons of bitches, to break them.

“The commander ordered --- 'To the river!' Some swam, some floated with logs. Hell on earth! Do you hear me, Pan [Mr.] Abelevitz, hell on earth, men in hell! Above us shellfire, below us rifle-fire. The Germans shooting nonstop, bullets hitting the water like rain, shellfire creating pillars of flame, and you could see lines of men swallowed up by the river. It drives you mad --- hell, I said, hell. You stand facing the river, and you see bodies of heroes being dragged by the current --- are they alive or dead?

“And here comes a second wave of soldiers diving into the river. They're pushing a few bundles of wood in front of them, on top of which are their rifles and ammunition. Meanwhile, the Germans are raining fire and cracking open the bundles, which explode with a deafening noise and sink to the bottom together with our men.

[Page 338]

“And so it was with a third wave, and the river filled with bodies. Already it's dawn and the red sky illuminates the river and the wild waves, and all the men are dead.

“You know, Pan Abelevitz, the Germans allowed the Russian tanks to drive onto the bridge and then blew up the bridge. My G-d! Flames shot up from the bridge and then it collapsed, taking to the bottom all the men and all the tanks. How they flew into the air --- pieces of men and pieces of steel --- and then sank to the depths.

“Silence blanketed the river. The waves grew calm. The sun was already at the edge of the sky, illuminating the river --- and it was red. Tens of bodies floated there. May the Name of the Creator of the world and its destroyer be magnified and sanctified.”

A tired morning slowly awoke. From the distance, warning sirens could be heard from Berlin. Once more, the artillery had received permission to speak.

|

|

| View of Opsa |

Footnotes

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Braslaw, Belarus

Braslaw, Belarus

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 10 Nov 2020 by LA