|

|

|

[Page 104]

by Dov Kaufman

|

|

|

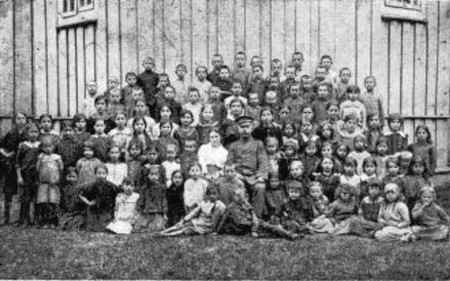

| The School During the German Occupation (1917) |

|

|

|

| The School in the Early Twenties |

|

|

| The School in the Academic Year (1927) |

|

|

| The School at the Beginning of the Academic Year (1928) |

|

|

| A Lag B'Omer Outing of the Schoolchildren (1930) |

|

|

| A Lag B'Omer Outing of the Schoolchildren (1931) |

As was the case in all the towns, we too, had Rebbes and teachers who taught the children Pentateuch and the Prophets. Among them were also those who would teach a bit of penmanship and arithmetic, that is, the ‘four skills.’ Most of the Rebbes were cruel to the children, and they saw this as quite natural, from the standpoint of the ‘means’ of study and education. The Rebbe would explain in accordance with his understanding, but the child would not understand the explanations, and accordingly, the Rebbe sought to literally ‘beat’ his lesson into the head of the child by means of blows, pinches, and a variety of bizarre punishments.

Among the last of the Rebbes, R' Benjamin Stotsky, and the ritual slaughterer Eliezer Pisecner, and R' Alter Shmulewicz were well-known. R' Alter was a more ‘reformed’ Rebbe, and he also taught secular subjects. understandably as a peripheral consideration.

From the time that R' Chaim-Noah Kamenetzky came to our town to settle there, a strong change began in the education of young boys. The convention was, that when a boy completed his Heder studies, his parents would send him to study in one of the Yeshivas, or he remained at home and studies the Gemara under the direction of one of the ‘young men’ who occupied a bench at the synagogue. Part of these boys would continue by themselves in the study of secular subjects, would be ‘affected’ and leave as ‘apostates,’ according to the perception of that generation. However, from the time that the ‘Modern’ School opened up, parents began to perceive the issues surrounding education differently, and their thoughts became further changed towards matters of the faith as well. In that period, the socialist movement also got started, which also had an influence on the direction of thinking among a well-recognized part of the residents of our town.

The school of R' Ch. N. Kamenetzky was full of boy and girl students from end-to-end. The subjects included were: Literature, geography, history, Tanakh, and arithmetic. Literature was suffused with Zionism, and a young man who came out of this school hoped and dreamt about the return to Zion, and a homeland re-established. A ‘new world’ was opened up in front of the children, but there were those who treated this ‘new world’ derisively. I remember an episode in connection with this: We were sitting in a lesson of

[Page 105]

arithmetic (in the house of R' Leib ben Ber'keh Odzhikhowsky); Suddenly, the image of a carriage drawn by two horses was reflected on the window, from the village of Tomaszowska; one of the students leaped up from his place, and asked with something less than seriousness – Rebbe, do you know how much these two horses are worth together?… The Rebbe, Ch. N. Kamenetzky did not get angry, and answered calmly: I do not know, but for sure there are people who know how to think about such things as well….

The ‘Modern’ School of Ch. N. Kamenetzky was opened in the year 1901/2; in the year 1903/4 R' Yaakov Beksht opened a ‘Modern’ School, who attracted the elementary students to him; in the year 1912/13 ‘Modern’ schools of this sort were opened by Aharon Dykhowsky, and also R' Alter Shmulewicz, who had few students, and also Eliyahu Sokolowsky.

In the year 1913/14, Ch. N. Kamenetzky ceased running his school. I was among the last of the students to complete their studies (under private lessons) with him. For a time afterwards, I was just wandering about, and I didn't know where to turn, or what to go on to do. In the end, I decided to study Talmud in a group, and also to continue with secular studies at home.

During the war years (1914-1918) children studied with the presence of the war and its potential disruptions. The Germans declared compulsory study in government public schools, but the question of Jewish national education remained standing. The town began to grapple with the establishment of a school, supported by the parents, in the place of a private Heder system. In the German school (in the afternoon) there were also Hebrew studies (by the teacher Weiss and one other). These studies were the foundation for an independent school, that was directed under the aegis of R' Joseph Rudnick, Ch. N. Kamenetzky and a number of other prominent townsfolk.

In the year 1919/20 (in the period of the war between the Poles and the Bolsheviks) learning continued. Among the teachers of that time were also teachers from Lida (Cygelnicki and others).

In the year 1921/22, a teacher was gotten from Zhetl (Epstein), a successful and skilled teacher who captured the hearts of parents and students. In the year 1923, the Poles began to introduce changes into the curriculum, and demanded that the school be placed on a government level. From that time, we went over from the public school, and they were re-organized from anew in the general school (in the women's section of the synagogue). I took on the direction of the school. Eliyahu Sokolowsky was retained for religious studies, and a graduate woman teacher was retained to teach Polish and arithmetic. The school was under government supervision, and in general, stood at a high level. However, the economic conditions were catastrophic, and there were simply no sources of public funds for the sustenance of the school. The burden on the parents was very great. The local teacher especially suffered from this, because the entire burden fell on them. There were months at a time, when the teachers did not receive their salary at all. It was only the will to keep the school going that made it possible to continue under such difficult circumstances.

In the year 1926/27 the situation got slightly better, thanks to the drama circle. Despite the fact that all its income was dedicated to the opening of a Fire-fighters brigade, from time-to-time they also covered joint expenses of the school. The school became affiliated with the Tarbut network of the Vilna district, and we learned in accordance with the curriculum of this network. The local Rabbi, R' Shabtai Fein, did not get

[Page 106]

involved with our internal issues. He would occasionally come to visit and test the students in Pentateuch and Prophets. In the school leadership were the Rabbi, and the representatives of the parents and teachers.

We favorably recall the teachers Esther and Hinde who gave much to create the good name of the school.

I continued to direct this school until 1931. Because of my desire to make aliyah, I received a work offer in a town beside Slonim (at three times the salary in Belica), in order to cover the costs associated with the making of my aliyah.

In the year 1930.31, a group of young activists organized itself with the help of Ch. N. Kamenetzky (who was at that time the head of the bank) and they undertook to build a building to be jointly occupied by the school and the bank. The money to do this was obtained by taking a loan from the bank, a levy placed on the residents of the town, support from America, and also support from the local ‘Hevra Kadisha.’ I no longer served as a teacher in the new school building, because at the same time, I got my paperwork in order, and made aliyah to the Land of Israel. The teachers were: Hirsch-Eliezer Shimonowicz and his wife, Yaakov Beksht and Eliyahu Sokolowsky.

The scions of Belica did not have the privilege of continuing their studies and education in the new school. With the entry of the Germans into the town (1941), the school was destroyed and afterwards, the dear children were exterminated.

Finally, I will underscore the teacher-educators, and the Rebbes-Melamdim that we had in Belica. itself, and those that served in the direction of the teaching of little children in those houses in other locations – all of them gave much to the teaching and education of children, and to the sustenance of the position of culture and Torah in our shtetl and in that of other towns in which they served.

Teacher-educators: Eliezer Itzkowitz, Rachel Itzkowitz, Shimon Buczkowsky, Baylah Belicki, Luba Belicki, Eliyahu-Nahum Belicki, Yaakov Beksht, Aharon Dykhowsky, Leah Halperin, Gershon Wismonsky, Eliyahu Yankelewsky, Aharon-David Mayewsky, Eliezer-Meir Savitzky, Eliyahu Sokolowsky, Dov Stotsky, Leib Poniemansky, Dov Kaufman, Abraham-Hirsch Kaufman, Chaim-Noah Kamenetzky, Issachar Kamenetzky, Zerakh Kremen, Rachel-Luba Shilovitzky, Hirsch-Eliezer Shimonowicz, Isaac Szeszko.

Rebbes-Melamdim: Moshe Belicki, Hirsch'l Baranchik, Eliezer Yankelewsky, Herzl Novogrudsky, Shimon Novogrudsky, Joseph Sokolowsky, Benjamin Stotsky, Mordechai Stotsky, Ozer Poniemansky, Eliezer Pisecner, Alter Shmulewicz, Yaakov Shmuckler, R' Shmeryl.

by Menachem Niv (Max Jasinowsky)

Who will erect a memorial monument to my beloved shtetl, tiny and poor, in which I was born, and in which I spent (with interruptions) the best of my years?

My shtetl, I have attempted to the best of my ability, to impart this feeling that I have, for the way of life within you, to convey it to the generation younger than I, the yearning to change the way of life, but together with this, I remain astonished to this day at the experiences of this tiny little town, numbering approximately 170 families, whose existence (oh, what an existence!) Depended on the ‘market day’ on Wednesday. The daily life brought with it, the establishment of institutions to the pride and utility of the residents of the town, institutions who, not only once, were the product of the work of few individuals ‘fanatic to the issue’ in question exclusively.

Here is a Savings & Loan bank, the life's handiwork of R' Chaim-Noah Kamenetzky and Yaakov Kotliarsky, who established it, nursed it, and led it to their last bitter day. This bank began to function in a side room (rented) for only 2-3 days a week, where in the evenings, they allocated the loans and received payments, and its continuation – a serious banking institution, from which all the residents of the town enjoyed the benefits of its blessed undertakings. It also encompassed the function of a Gemilut-Hasadim, the work of Ephraim Ruzhansky, and in this manner the Bikur Kholim group functioned, whose income was derived from anonymous contributions, and from the appearances of ‘Purim Plays’ on Purim.

The Fire-Fighters Brigade, with their instrumental orchestra beside them, was the handiwork of a clutch of young men, who did not stint on money or time to buy these expensive instruments. And the salary of the director, and for a while also the conductor, all of this was secured by individual effort.

And the youth groups, who can count them all?: “HeHalutz, HeHalutz HaTza'ir, and finally, Freiheit, and the Scout Organization on whom I, especially want to focus my memory, because I stood beside their cradle, and was one of the ‘midwives’ that saw to their birth.

[Page 108]

A. Freiheit and Scout Organization in their Work

Previous to these, the HeHalutz and for a while, also HeHalutz HaTza'ir existed first. Despite the fact that their educational activities were very important, and most of the young people in the town belonged to them, yet only a very small number of them made aliyah to the Land of Israel. An important change took place in the year 1931, the time when the Freiheit institution (a.k.a. Dror) was established, for those age 18 and up, who also belonged to HeHalutz, and many of them enrolled in training and made aliyah. Freiheit, and the Scout Organization (as a feeder group) for the ages of 8-10, and while the activities of the Freiheit did not encounter any special difficulties (the members already were on their own recognizance), the work in ‘Scout’ was not easy. Who does not recall the mocking calls of : ‘Friendship,’ ‘Be Young’ (our mottoes), ‘Red Bands’ ( because of the red thread in the shirts of the movement). The fear of the parents was disturbing, who, as it happens had nothing to fear, but were afraid that their children would become ‘Reds,’ God-forbid. Nevertheless, the children and young people were drawn to us, because the activities and outings enchanted them, as did the uniting uniform, the dances, the singing of national songs, and in the more distant future, the going out to training and aliyah to the Land of Israel.

We were totally without experience in the guidance of children and young people, who needed as part of their education an introduction of the elements of vision. Who, in those days knew anything about seminaries for leadership or study days? The emissary from the central office would come at infrequent intervals, and he had little experience.

In our vicinity, there were only two branches of Freiheit (in Lida and with us), and as a result the relationship between the two of us was very intense: meetings, and assemblies, walking trips, and sleep overs for the older members (from Lida to Belica) and the crowning activity – a summer camp at Yud'keh's beside Lida, in a village house. It seems to me that this was one of the most enjoyable summers for the participants in the camp, and for us, the leaders, despite all of the difficulties involved.

And who will not recall the blowing of the trumpets by Jonah Odzhikhowsky (then only 11 years old) calling us to rise, to eat, to work, to take a hike, and then go to bed. What joy we got from the community meals that we took together at a table under the tree, the song and the games that Moshe'leh Novoprucky from Lida led with such skill, and the hikes in the surrounding forests, the visits with the ‘Yishuvniks’ etc. The summer residence captured the hearts of all who participated, and when we returned to Belica, we were not oriented to forget those wonderful days, and we were compelled, as a result, to get out into the forest from time-to-time, for at least a day.

The activities of these two institutions, previously mentioned, opened up widely and deeply, and left its stamp on the entire life of the town. In 1933, I was compelled to terminate my strong connection [with them] because of my own departure for training. I returned for some months in 1934, and then made aliyah. I knew that these institutions continued to develop in the coming years, and a small part of the older Scouts moved on to Freiheit, went on to training, and was also privileged to make aliyah, but the larger portion did not accomplish this.

The forests in the area no longer served as a ‘summer camp,’ or for hiking, but rather as camouflage in the face of that terrifying enemy, the beast in human form, against which the partisans fought, and, in part, died. I am certain that their strength of spirit in standing against this prowling beast, was suckled from the disciplines of their association with Freiheit and HeHalutz.

[Page 109]

B. The ‘Theater’ of Those Times

|

|

| Participants in the Play ‘Ukrainian Pogrom Martyrs’ that was put on in 29 Nov 1930 |

|

|

| From the Youth of the Town |

I remember the ‘Theater’ in the shtetl. I was a little boy, but I nevertheless went after it from its inception, until I got older, and took part in the productions, as an actor, and also in the organization of productions.

The living spirit and the driving force to start up favored plays in Belica was a young man who worked for a time in the town with leather tanning. He was called ‘Der Shishlevitzer’ after the shtetl of Svisloch from which he came (he was a relative of the family of Abraham Khlavneh's). They started with a presentation of ‘Die Gebrokhene Hertzer,’ that took place on the second floor of the building that belonged to Ben-Zion Stotsky. A stage was erected, a curtain was put up, and all manner of benches and chairs were assembled, and they put on the play. This was a very unusual occurrence in the town.

Along with Der Shishlevitzer, the following took part in the play: Chaim Lieb'keh's Dob'keh Lejzor's, Ziss'l Dash'keh's, Leib'eh der Minsker, Mul'yeh, Chay'keh-Shakhna's (der ‘Gubernator’), Dov Kaufman, and others. Makeup was whatever Der Shishlevitzer could improvise, however, there was no special material for this, so he used his smarts, and made the beards from flax. When the makeup caught fire, and the beard of Chaim Golda's started to burn, and his face was singed, this did not stop the production from going on, with considerable success.

I do not know if the need to put on plays came from some inner drive of ‘talented’ people, or from the need for resources to establish and open the library, and after that, the Fire-fighters Brigade, and orchestra. Who can count all of the [sizeable] needs that always stood in reverse relationship to the small and impoverished town.

In due course, we put on the plays ‘Herschel'eh the Relative, The Slaughter, The Seven Who Were Hung, The Dybbuk’. Most times the shows were put on in the ‘stodala’ next to the cows and chickens, who took no notice of the onlookers and went about their own affairs… As you can understand, there were no lack of ‘critics,’ for example, on the evening when they put on the short play, ‘A Rebbe had 10 Little Daughters,’ the crowd reacted by throwing wet towels at the ‘artists.’

A special event was: obtaining police permission for the plays, an event that was dependent on the good will of the policemen. It was not only once that R' Lejzor ‘Der Jeremicer’ – the Gabbai of the synagogue – save the day who would buy off the sentiment of the police with a few bottles of strong drink.

The desire of the young generation, that succeeded in seeing real theater in the big cities, grew in wanting to give the town something more ‘modern.’ At that time they had erected the ‘Serai’ of the Fire-Fighters

[Page 110]

Brigade, that also served as an auditorium for presenting plays, with a wide stage, cupboards for costumes and a pit for the prompter (the commitment to get this addition had no bounds). On the evening of a presentation, the fire engines would be taken outside, the water barrels, etc., arrange all of the benches, and put out the large candelabras, which we would take from the synagogue.

Of the younger generation, who partook in presentations at the side of the ‘veterans,’ I will recall Dvora'keh Dash'keh's, Rachel'eh Itzkowitz, Rachel'eh ‘Die Mameh's’, Alinka Chaya-Dvor'keh's, Bash'keh ‘Die Mameh's,’ Dov Grodinsky, Dov Kaufman, Ziss'l Dash'keh's, Chaya-Baylah Shimonowicz, Mendl Chay'keh's, Feiga-Et'keh Chaim-Reuven's, Malka Zerakh's, Yankl Zerakh's, the teacher Motkow, Abraham Maggid, and others. As prompters, the following served: Itchkeh Chaim-Noah's, and Gershon Wismonsky.

We were our own players, stage hands, makeup artists, and set-builders (with a lot of help from Der Kayser), with whatever good hand, and all of this with boundless commitment, a serious relationship and from the desire to give the audience a genuine presentation, according to our understanding. I remember, that in the play, ‘Gott, Mensch und Tyvel’ Dov Grodinsky played the part of the ‘Tyvel’ (The Devil), who was supposed to be entirely black, with long fingers and with the horns and ears of a cow. Dov wanted to be ‘genuine,’ and so he sewed a sort of headdress to which he added a pair of horns, and the ears of a cow, which he had procured from a meat store. Despite the considerable salt that he shook over them, he could not eliminate the bad smell that forcefully emanated from them, and it was difficult to stand next to him on stage. For many days, Dov could not get the color of the coal off of himself, and the stink from his body, all in order to appear as a genuine devil…

As a supplement to our plays, every year at Purim time, we would put on the play ‘The Selling of Joseph,’ whose income was dedicated to the Bikur Kholim. Excerpts from this play would be presented in ordinary homes, and the full production in the synagogue. With the erection of the ‘Serai,’ it became a coveted location, and the ‘Joseph Play’ was put on there, despite the intense cold. The cold did not prevent the community from filling the ‘Serai,’ to the point of no room left, with the men dressed in their fur coats, and the women all tied up in kerchiefs. At the time that the brothers threw Joseph (Fyv'eh Lip'keh's) into the pit, wearing only his coat of many colors, apparently the Patriarch Jacob (Shef'teh ‘Der Shtepper’) was afraid that; ‘his dear son’ would catch cold, and he put half of his body into the stage, and threw a fur coat down into the pit. This pleased Feiga Liebeh's, who sat in the first row, and she added: ‘He is a father, after all….’

Yes, all of this was and has passed into history, that was so cruel to our people, and did not pass over my beloved townsfolk. this was, and is no longer…

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Belitsa, Belarus

Belitsa, Belarus

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 12 Aug 2022 by JH