|

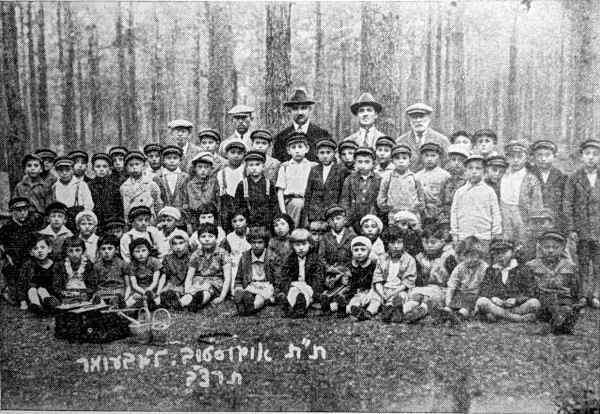

Caption in photo:Students of the Talmud Torah, Lag Ba'omer,[23] 5692 [1932]

|

|

[Page 285]

by Dr. Moshe and Eliezer Markus

The economy in the district of Augustow was based on agriculture. The city itself served as a commercial and administrative center for the many villages that were around it. All of the commerce (except for the sale of lumber), the craft and the few industrial enterprises that were in the city served, essentially, the agricultural population that was in the area.

The district of Augustow was partly covered by forests and lakes. On the open and fertile lands, there grew all kinds of grains, flax, beans, fodder, and vegetables. Other parcels served as pasture lands for cows and horses. The villages were populated by Polish farmers, mostly agriculturally based, whose livelihood was on their land. And some of them, lacking plots of land, made their living in the wood industry, fishing, building work in the summer, and all kinds of simple work.

The main branch of agriculture was the cultivation of field crops: wheat, barley, and oats. In the villages there were almost no crafts people. The crafts people in Augustow, tailors, shoemakers, hatters, smiths, leather workers, carpenters, glaziers, painters, metal workers, bakers, and more – were Jews. They were supported by the sale of their products to the farmers in the area.

Commerce was in the hands of the Jews. Only in some of the villages were there Polish shops for the sale of grocery necessities. These stores were established after the liberation of Poland, when the empowerment of the regime began to develop the movement in the state for the conquest of commerce from the hands of the Jews. However even then these shopkeepers purchased their necessities from the Jewish wholesalers in Augustow. The farmers arranged most of their purchases on the days of “the market.” On Tuesdays and Fridays of the week the farmers would come to the city on their wagons; with them were the members of their families. They would sell their products, and would buy all that they needed in food, clothing, and household goods. Some of the farmers in the nearby area attended the Catholic church in the city on Sundays. They would take advantage of this opportunity to sell their products and arrange purchases in the city, to repair the wagon, to shoe a horse, to repair a harness, or order boots.

3-4 times in the year there were big “fairs.” Then farmers from the near and far surroundings would gather in the city market and the adjacent streets. Travelling Jewish merchants who sold their merchandise from temporary stands would also come. On the days of the “Fair,” many work animals would pass from hand to hand, animals for slaughter, wagons, sheep and goats, pigs and the like. Market days and the “fairs” were an essential source of income for the Jews of the city. The farmers would bring to the city of all the goodness of the land;

[Page 286]

potatoes, onions, wheat and barley, vegetables and fruits, poultry and eggs, dairy products, mushrooms and berries, etc. The products were purchased mostly by housewives, and partly by merchants who would sell it afterwards in the Jewish houses, or export it outside of the forest. After selling their products, the farmers would turn to the many shops in the market and the adjacent streets, which were all in the hands of the Jews, and would buy sugar and salt, groats and oils, kerosene and candles, tea and tobacco, salted fish, etc. As needed, they also acquired fabrics, especially for the women, although most of the garments for the men and women were self-woven. Weaving on home looms was still widespread in all of the village houses. The women primarily engaged in this on the long winter nights, when there was little work on the agricultural farm. They would bake their bread themselves from black grain flour. But for Sundays of the week and holidays, they would buy from the Jews challot made from white flour, and sweet baked goods.

Market days were also primary revenue days for the Jewish pubs that were in the city. On these days the farmers would enter the pubs for the purpose of drinking for its own sake, or for the purpose of marking the completion of business (the acquisition of equipment, a horse or a cow); they would drink brandy and beer, and finish it off with salted and smoked fish, eggs and sausage. On the rest of the days of the week the pubs were empty, and only a very few of the Jewish residents of the city, primarily waggoneers and porters, and some of the local gentiles, would enter them.

Augustow was a district city, and the seat of the district government. In it was the district courthouse, and the notary who was in charge of the registry of plots of land and buildings. The villagers frequently needed these authorities, and they frequently visited in the city. The commerce and the industry were, as was mentioned, in the hands of the Jews, and therefore we find that that all of the shops in the market square and the streets that branched off from it belonged to the Jews, and the matter was the same in the many workshops. It is no wonder, then, that on Shabbat and festivals all work and all commercial negotiation stopped, and the rest of the holy Shabbat was spread over the whole city. In the city there was one pharmacy, whose owner was Ploni, and two stores for the sale of medications made by uncertified Jewish pharmacists. Actually, the Jews and even the gentiles turned specifically to the medicine stores of the Jews. The shop owners and the craftspeople existed principally by the proceeds from the farmers. One must take into account that the residents of the city numbered about 15,000 souls, upwards of half of them Jews, whereas the residents of the district who needed the services of the city, numbered about 80,000 souls. In addition to the craftspeople that we mentioned, there were also fabric dyers who dyed fabrics and threads that the farmers would bring them, coppersmiths, and makers of metal utensils and vessels, potters, makers of roofing tiles, and roof tilers. There were also a few butcher shops, which mainly served the Jewish residents, and the treif[1] animal meat was only sold to the gentiles.

From fear that there would be a majority of Jews on the city council, the Polish authorities added to the city, for the needs of the elections, villages from the area that were populated only by gentiles.

Among the many and diverse livelihoods in which the Jews of the city engaged, the waggoneers and porters must especially be mentioned. The freight wagons were engaged in transporting merchandise from the train station, 3 kilometers from the city, and also in transferring merchandise and heavy equipment within, and outside of, the city. There were also carriage wagons (britzkas), whose main business was transporting people from the city to the trains that went out from the train station twice a day, and the bringing of those arriving on the train – to the city.

[Page 287]

There were those who used these means of transportation for the purpose of trips to the forest, for example. In the winter, with the falling of snow, the carriages were replaced by sleds.*[2] Tens of Jewish families were supported by this transportation. The porters were also almost entirely Jewish. They stood out as a typical group of those with physical strength, against the background of the general human landscape of the Jewish population. A special livelihood was that of the water drawers and transporters of the city. Water for drinking and cooking was brought from the big lake on which the city**[3] was situated. A transporter of water would pour the water into a big barrel, which was loaded onto a wagon hitched to a horse, and sell it by the bucket to all those who needed it. This livelihood was, more than the rest, in the hands of the Jews, but in the last years it passed to the gentiles, for the Jews tired of it. The wood cutters were gentiles. The farmers' sons were free in the winter from their agricultural work, together with the horse and wagon that they had on the farm. They would cut the trees in the forest into individual sections, bring them to the city for sale. After them workers would come to chop the wood into pieces suitable for heating in the ovens in the winter, and for cooking on the stovetops all the days of the year.

It should be mentioned that between the First and Second World Wars, when the Zionist youth movements were developed in the city, training groups of “HeChalutz,” “HeChalutz HaDati,” and “Beitar,”[4] were established in Augustow and the surrounding area that gripped the youth in physical work as a source of training and financial support. The sight of Jewish youth wood cutters in the yards of the Jews turned into a regular sight in the city.

Since Augustow resides next to large lakes, the profession of fishing was widespread in the city, and the Jews too had a significant part of that. The government had the practice of leasing the lakes; the tenants were mostly Jews. Jews were also engaged in the work of fishing itself, but essentially – gentiles. In addition to licensed fishing, it was widespread to fish without a license. These “fishers” would, with a rod or a small net, pull out fish from the river and sell them in the houses of the Jews. Because of the great amount of fish in the lakes (there were in them many kinds of excellent types), they were one of the primary foods of the residents of the city. On Shabbat in all the Jewish houses they ate fish, even in most of the houses of the poor. Many Jewish families were supported by the fish. One Jew engaged in the preparation of smoked fish from the fresh fish, and salted fish, which had a good market not only in the city, but also in the surrounding area. Another Jew engaged in making sausage and smoked meat. Soap production was also in the hands of the Jews. Although in the last years the people of the city began to use soap imported from the factories that were in the large cities, indeed the residents of the villages preferred the simple and cheap local blue, white, and yellow laundry soap. Many of the Jews from the city also continued to use it. The soap was made from the milk fat of animals, which was unacceptable for eating, and supplied by the butcher shops and the slaughterhouses.

One of the Jewish livelihoods was the rag trade. The rag sellers would buy all the rags and worn-out clothing in the city and the area, and would sort them in their store houses. Linen – separately; wool – separately. They would export the linen to Germany, and they would bring the wool to Bialystok, for the large textile industry that existed in that city.

[Page 288]

The manufacture of ropes was also among the Jewish livelihoods, and for the most part it was coupled with the making of saddles and straps for the bridles of the horses and wagons.

Since the district of Augustow was rich with forests, lumber for building was relatively plentiful and cheap. For the construction of their houses the farmers used wooden beams that they bought or cut in the nearby area. The farmers' sons who still lacked independent farms, engaged in the work of building. In the city they would also build houses of wood in the suburbs and the side streets, and there too the builders were gentiles. On the main streets of the city buildings made from bricks were already raised. The Jews were building contractors, who saw to the execution, however the work itself was done by non-Jewish workers. Only in plastering, painting, and framing were there Jewish workers. There were three brick factories in the city. Their owners were Jews, but their workers were mostly gentiles.

Augustow was, as is known, near the German border. The currency of things was the smuggling of goods from one country to the other. Primarily the resident farmers of the villages adjacent to the border engaged in this. The middlemen and the coordinators of the commercial activities connected to smuggling were Jews. In the days of the Tsar's regime, when young Jews, before being called up for the army, needed to cross the border without a permit, in order to emigrate to America and other countries across the sea, these smugglers would help them cross the border to Germany. The Jewish smugglers were known to the community, and they called them “Mistachnim.”[5]

The manufacture and commerce connected to the wood industry occupied a special place in the economy of the city and the surrounding area. The forests that extended over thousands of square kilometers, and the network of streams, lakes, and the canals that joined them, turned Augustow into one of the centers of the wood trade in Poland. The trade in this area was entirely in the hands of Jews. But the work of cutting down the trees, bringing them out of the forest, binding them to rafts and moving them by way of the rivers, lakes and canals to Danzig, was done by the local farmers and their sons. The supervisors and administrators of the work in the forests were Jews. Most of the forests were government-owned, and only a small part of them belonged to the landholders in the area. Parts of the forest were turned over to lumbering by auction, which took place in the chief office of the forest authority in Poland, in the city of Shedlitz. The forest merchants were for the most part wealthy. In “fat” years, when the wood market in Germany was good, the profits were great. The merchants enjoyed a high standard of living, and generously distributed donations for public needs. This industry supported many Jewish families of work administrators, surveyors, appraisers, supervisors, and those engaged in secondary production, such as collecting the sap of the trees and processing it.

Industry for the most part served the local needs and those of the surrounding area, and was entirely in the hands of the Jews. 3 flour mills, one of which was operated by the water power of the Augustow canal, 2 sawmills, 2 beer breweries, 2 tanneries, 2 brick factories, 1 factory for porcelain tiles; these constituted the industry in Augustow. The flour mills were small and their owners engaged also in selling flour. Most of the workers were Polish. The sawmills employed a great number of workers, however all of them were Polish. For some reason, it was precisely in the tanneries that Jewish laborers worked.

In the days of the Russian regime the tanneries[6] would export their products to greater Russia. With the establishment of the independent state of Poland, the markets contracted and the big tannery closed.

[Page 289]

In a few villages in the Augustow area at the beginning of the present century[7] there still dwelt a few Jews, who engaged in trade and in craft. Smiths, tailors, shoemakers, etc. lived in Yanovka, in Raglova, Sztabin, Lipsk, Tzernovroda, Gortzitza, Mikaszówka, and others. By virtue of a command from the Tsarist government, the Jews were expelled from the villages. Most of them moved to the cities, and some of them emigrated to lands across the sea. More than a few of the Jewish population in Augustow were of those who had left these villages. Sometimes there remained in their personal name an association to the name of the village where they previously dwelt, such as: Ploni the Lipsk man, or Almoni the Sztabin man, (The Lipsker, the Sztabiner, and the like).[8]

The Poles took the place of the Jewish shopkeepers and craftspeople.

Jews were supported also by the leasing of orchards of fruit trees etc. from landowners. A few Jews engaged in growing vegetables within the city, and this was their livelihood.

In the district of Augustow there was also one Jewish landowner (Binstein).

Within the economic system of the city, there were tens of other livelihoods. These were in craft, in commerce and services that were integrated together to provide the needs of life in the city and the area, such as: watchmakers, bookshops, whitewashers, metal workers, electricians, etc. Doctors, medics, lawyers etc., Rabbis and shamashim, Chazzanim and shochtim, officials and teachers, all of them together constituted the diverse spectrum of the livelihoods in the typical Jewish town in Poland and in Lithuania.

The Jews existed and developed despite the generally hostile relationship on the part of the authorities. As a counterweight against the actions that were intended to narrow their steps and dispossess them of their positions, the Jews established internal institutions for mutual aid. At first these were funds for Gemilut Chassadim. A small merchant who was in need of operating capital, a craftsperson who sought to acquire a machine or equipment, a waggoneer who was forced to buy a horse in place of the one that “fell,” all had their needs fulfilled with the help of the associations for Gemilut Chassadim in all their forms.

At the beginning of the century, the cooperative movement began to be developed among Russian Jewry. In its footsteps a small cooperative fund was also established in Augustow, which gave small loans to craftspeople and small shop-owners.

After the First World War, with the expansion of the Jewish cooperative credit movement in Poland, a Jewish cooperative bank was established in Augustow that existed until the outbreak of the Second World War. This bank, which was greatly developed over the course of time, was an important support and protector for the economy of the Jews in the city. At the head of the bank stood important community leaders, merchants and craftspeople. Over the course of many years Reb Binyamin Markus, may his memory be for a blessing, served as head of the administration.*[9]

The economic lives of the Jews of Augustow were primarily based, therefore, on the forming of connections between the village and the city, and on the provisioning of the needs of the farmers. In this way Jewish lives developed over the course of hundreds of years, and became consolidated into a social and cultural way of life, which formed the character of eastern European Jewry.

Serious changes to this structure began after the First World War.

With the establishment of the independent State of Poland, a national movement began to act for the conquest of commerce and manufacture from the hands of the Jews. The great development of manufacturing in the cities, on the one hand, and the cultivation of the status

[Page 290]

of the merchants from the country with the help of the authorities, on the other hand, pulled many livelihoods out from under the feet of the Jews. The field of sustenance for the Jews contracted and disappeared. The lack of work, especially among the younger generation, increased. The governmental system, in all its institutions and activities, was closed in the face of the Jewish youth. The great and heavy industry was for the most part “purified” of Jews. The schools of higher education instituted “numerus clausus.”[10]

The tax policy of the government was intended to weigh heavily on the Jews, and to deprive them of their livelihoods. For the Jewish young generation there were no opportunities in the state of Poland. This situation pushed the Jewish youth to emigration and aliyah to the land. This path also shrank with the closing of the gates of the United States and the land of Israel. Depression and anguish reigned in the Jewish population even before the Second World War. In this atmosphere of lack of resources, a great yearning for redemption, and hope for the breaching of the closed gates[11] of the land of Israel, the Nazi vandals came and destroyed life and property. They drowned Augustow, together with the thousands of holy congregations throughout Russia, Poland, and Lithuania, in a sea of fire and blood. May God avenge their blood.

Translator's Footnotes:

by Meir Meizler

When all of the teachers assembled for a proper consultation on what to do to improve our status, I then acquiesced to their request and wrote these words.

These days are not like the first days for we teachers. Days arrived that no one desired, evil days of trouble, for instead of the days that passed in which people's needs were few and the income great, now the matter has become the opposite, the income is little and meagre, and the needs are great. It is the case in this year too, where the high prices will increase from day to day, and the money that we previously spent to support our household over the course of a full month, is necessary for us at this time for one week's living, and all of us are expecting to starve, and if we are not for ourselves who will be for us?[1] Therefore we have gathered together as one, friends, to investigate and to seek the origin of the evil and the source of the trouble, maybe it will be within our hands to improve our situation, which is very terrible and horrifying, and who will give us a chance?!

Indeed, if a person becomes sick and falls on his deathbed, it will happen that, if the people of his household are quick and diligent they will hurry to call for the doctor, while most of his bones are still strong and his illness has not overcome him, his healing will quickly develop. But woe to him, to the person whose household members are indolent and lazy, and when he falls into his bed they say: “but it is an illness and he will carry it, an illness that develops and passes,” for his illness will be strengthened from hour to hour, the pillars of his back will weaken, and he will reach the gates of death, until the people of his house will pull themselves together

[Page 291]

to call the doctor, and will also succeed with a great deal of toil and trouble to find a remedy to cure him, and also remove his very old illness from him. But what is his lot in life even after his recovery? Weak, lacking vitality, and extremely powerless, and many days will pass for him until he returns to his original strength, for his illness already consumed half his flesh, and extracted the sap of his vitality. So the matter is with us today; we have not assembled to give advice to ourselves before the damage spread within us. It can be that we have dwelt at this time quiet and serene, we did not know any worry, and in the days of the rest and the calm, we have truly rested and found serenity for our souls that are exhausted from the hard work which we worked all the summer. But the problem is, each of us turned to themselves. And not alone, but no man gets sick from his friend's disaster, except that each one built a stage for himself and says: I am a sprinkler son of a sprinkler![2] There is none like me! And for me it is pleasant, and for me it is suited,[3] and the one who is lifted above all as chief,[4] and he will not return to his heart and say: Isn't there a lie in our day? And why should all the nation say “holy” to the one who will say “I am holy”? Indeed, my friends, he too, like me, was created in the image of God; he too has to live on the face of the earth, and to sustain his house with bread. Of all these he will not know and will not want to know and will not relinquish what is his even for a sandal strap[5] therefore the one will assemble in his room like a flock of students, herds and herds too many to count! Indeed, he will eat meat to satiation, and for his neighbor, a person who like him was created in God's image, he will leave hunger[6] and lack of students. And therefore, this trouble comes upon us, for foreign teachers will increase their thinking that great happiness is hidden in this site, and all the more so will they take it upon themselves. If it is so for the small teachers, for the big ones how much more so, indeed their fortune will increase to thousands and tens of thousands! Happy is the man who is satisfied with his lot to be a teacher in our community, and the evil consequence that emerges to us from it is that a few of our brothers, members of our pact, born of this city, die of hunger. They don't have even food for one meal in the full sense of the word, for this is a great principle in our community; they will take out the old before the new,[7] therefore they will favor the new ones recently arrived. For these the elders became obsolete, and put their sons next to them, in their image, for they brought a new Torah with them, which on one foot[8] they will teach their children to put in their mouths![9] Woe to the creations from the insult of Torah! The honor of the Torah is humble and humbling, and no one takes it to heart! What is the teacher in the eyes of the fathers and sons together? He is only the scum of humanity, a subordinate and loathsome object! He eats and does nothing, etc., and how will the Torah be able to be beloved in their eyes, if the carriers of its flag are despised and contemptible, and who is guilty of this matter? Woe to us if we say: We ourselves! In us is the blame! For in the way of the world, each person who wants to cover their nakedness, or will want to sew for themselves footwear, will seek and inquire after the artisan, will seek him and will find him, and we? Aha! We will cover our disgrace; our shame is too great to bear![10] We like poor people will go from door to door. Seriously and hunched over, shame-faced and with trembling heart, we will come to the house of one where we will search there for food, and like a ghost from the ground so will our speech chirp[11] before him, saying: Give me children![12] Woe to that same shame! Each and every day a Divine voice emerges[13] and proclaims, saying: the teachers are scornful of the honor of the Torah, and degrading to the land, its glory, and its splendor! The evil outcome that comes from this is that each one will speak ill of their neighbor, each one will praise himself, for like this one and like that one he will do great deeds,[14] (hah, how evil and corrupt is this attribute!) He will desecrate the honor of his neighbor, for what will a person not do in seeking food for himself and for the souls[15] in his house, indeed for a piece of bread a man will commit a crime!

This matter which we will go by ourselves to seek a student in contract law, although the matter is very worthy of contempt, as I have proven, yet nevertheless we have no further justification to comment on it, for each one's heart strikes him[16] and his life is precarious,[17] for if indeed we are believers who are the children of believers,[18] and every person knows

[Page 292]

that he will not take his part in his hand, and a person's food is measured for them, nevertheless every person will want to know what God has measured for them. We are not better in this than the rest of humankind, nor worse than them, and we will not be able to order a person to sit subordinate to him, and wait until the fathers will rise to open it. How much of the ugly and offensive is there in the matter, if there are found among us fools who are prominent, who arrive early to seek students in the summer days, from the day of Purim, and in the rainy season, from Rosh Chodesh[19] Elul,[20] and upon hearing the sound of the shofar[21] in the camp of Israel they proclaim liberty[22] for themselves and for the feeling of shame that is embedded in the heart of every person. They hurry to seek students and to arouse arguments with their neighbor, and the evil result that emerges for us from this is that the teacher and the student, the two of them together, will set aside their hearts from the learning. Indeed, the teachers will seek new students for themselves, and the students, for their part, will not be quiet and will not rest, and will seek for themselves new teachers, indeed will hurry to find them, and will no longer pay attention to the instruction of this their teacher, for all their interest is in the new teacher, and in this way the learning continues to be destroyed to its foundation, and what teaching will be upon it?

|

|

Caption in photo:Students of the Talmud Torah, Lag Ba'omer,[23] 5692 [1932] |

Translator's Footnotes:

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Augustow, Poland

Augustow, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 21 Aug 2022 by JH