|

|

|

[Page 189]

by Abba Gordin

I have barely any memory of Michaliszki, my place of birth. My father was taken on as a rabbi in Augustow. He emerged from under the wings of Reb Sender, who had aided him economically, and Reb Moyshele, who had aided him spiritually and intellectually. He was now ready to follow his own path, under his own steam, standing on his own two feet. He was a gifted orator and a rabbi with maskilic tendencies, and so he appealed to a wide audience of common folk, the Jewish masses. He was altogether saturated in the spirit of his times. He preached not only about piety, but also touched on “national questions” and spoke in particular of Chovevei Tzion.

Before his arrival there was the rabbi in Augustow, Reb Kasriel, who was cut from the old cloth: he distinguished himself with his expertise. He had quite a loyal following in town, composed to a large extent of members of his own extended family. But on account of a quarrel–a common occurrence that plagues Jewish life in small towns–he was forced to leave. He found a rabbinical posting not far from Augustow, in a tiny town which, in comparison, made Augustow look like a bustling metropolis, a major center of Jewish culture. Augustow's notable citizens, the elites, were close relatives of Reb Kasriel, but the common folks had risen up, the handworkers, led by the members of the burial society, led a mutiny and they triumphed. As a result the town's elite were enemies of the new rabbi on principle. They still hoped, by means of some machinations or other, to turn the communal wheel backward, to bring Reb Kasriel back somehow and restore his reign … At the time I knew nothing of all this, of course: being all of two years old I had little interest in communal politics.

One of the earliest things in the town that left a lasting impression on me, managing to make an enduring trace on my memory which is still there to this day, was of a curious well. The well was located in a neighboring yard, separated from the yard in which we, the rabbi and his family, lived. The well was fenced off by a railing with spikes along the top. What was most unusual about the well was that it had a hinged lid on the top, not unlike a little door, which was locked.

[Page 190]

The man who owned the yard, the house, and the curious well was also Jewish, but he was a fat, mean man prone to melancholy, a veritable dark cloud. He wore a pair of high boots and a hat with a polished visor, like a Gentile. He was such a penny-pinching misanthrope that he could not abide the thought of his neighbors using his water. Twice a day that miser would come out to unlock his well, draw two buckets of water for himself and lock the well again. His yard, too, was closed off, the gate locked: it didn't open from the outside as normal people's gates did.

We moved to a new apartment, to a larger, nicer place in a stone building located in the market square. The windows–three large, bright windows–looked right down onto the market itself. I could watch everything that was going on down there, and be seen myself. Everything I observed was so immeasurably interesting: there was the town clock on the facade of the town hall; there were the town gardens, surrounded by iron fences, all laid out with tree-lined promenades, with dark corners of thick shrubbery so perfect for playing games of hide and seek. Right at the very center of the park stood a bandstand for an orchestra. In the summertime the military band would play there every evening. On one side of the park stood a cathedral with proud cupolas which looked for all the world like gigantic onions or turnips.

Next to us lived a young couple: Esne, the eldest daughter of Sheyne Yudis, and her husband. They ran a wholesale grocery store and had their living quarters in the rear of the building: two spacious rooms with a kitchen, all exquisitely furnished. The corridor leading out to the yard, and the back porch were shared between our two apartments.

Sheyne Yudis, in addition to her grown up daughter and a son named Nisl who was three years older than me, naturally also had a husband. But she wore the trousers. She was renowned throughout Augustow. Their business was grain, and they had a full granary. I would go there to play with Nisl. What drew me to the granary more than anything was the musty smell, the semi-darkness, the flour dust

[Page 191]

which hung in the air, the cobwebbed corners which housed full sacks of wheat, corn, barley and rye. Being very small for my age, and flexible, I liked to hide between the sacks where no one could ever find me. But the greatest attraction of all was the tub of peas. I liked to roll around on top of the piled-up peas, enjoying the feeling of having peas run in under my shirt and into my shoes.

In the attic of their hay barn I played with my little sister Masha and a couple of her friends, playing a game we called “mothers and fathers.” My sister and the other little girls would take turns pretending to give birth, while I would be a combination father and obstetrician, helping the baby come out into the world and then raise it as my own.

Sheyne Yudis was a pious woman, and word would be passed around the town, with mocking intent, of her morning appeals to God from the Women's synagogue. She would come very early, before Minyan prayer service in the men's synagogue had even begun. Sheyne Yudis was on first name terms with the almighty and would speak to him in a very straightforward, familiar manner, not just in prayer, but constantly throughout the day.

– “I, your servant, Sheyne Yudis, am here. My husband, Tsvi Hirsh, is still in his underpants, but he will be along shortly.”

I was a regular visitor to the prayer house. I would walk around there with other children my age, circling the bima, rummaging around in the little pile of torn pages that had accumulated there. In those days, the prayer house in Augustow was always full of people. It was cheerful there–during the minyan of course, but also afterwards. The boys of the town, middle-class kids and their parents, would sit there around the long tables, or beside lecterns, reading aloud in a melodic singsong. There were also poor students, from other towns who “ate days”[1] and also a recluse or two. Large mantle lamps over the tables, lit by candles, in whose shine one read and studied the small print of the Rashi script.

The prayer house was filled with the singsong of students learning, but also the sound of mischief. It was more than a place of worship, and more than a house of learning, it was also like a clubhouse. Behind and on top of masonry stoves, slept guests, paupers who had travelled from nearby towns, wandering and begging.

The oven also served as a bed for the town madman Kalman “Tume veta'are.”[2] He would wander around,

[Page 192]

disheveled and bedraggled, in filthy rags with holes large enough to show patches of bare skin underneath. The hair on his head and beard was as black as pitch, and matted. His face, with its two glinting eyes, was battered and anguished. He wandered around, mumbling to himself, and the only words of his articulated clearly enough to understand were “tume” and “ta'are.”

In the center of the market square, right across from the middle window of the rabbi's apartment, was where they drilled the army recruits, teaching them how to march in the appropriate manner, which meant learning how to “goose step,” how to stand tall, stretched as taut as bows, frozen as still as statues. They were also taught how to hold a rifle, how to carry it on their shoulders, and how to pierce a scarecrow with a bayonet. Augustow, being a town not far from the German border, had a large garrison.

A regiment of Cossacks was stationed in town including–serving mostly as orderlies, servants to the officers–Kalmyks with earrings.

I was not indifferent to the soldiers' parades on the Russian public holidays. The soldiers and officers would all enter the Orthodox cathedral to linger for an hour or sometimes more. I stood with children my age, and also older children, outside in the market square, waiting patiently for them to reemerge. It was not too difficult in the summertime, but in winter, in the burning frost, waiting was pure torture. Our ears would freeze, our noses ran, our feet were like blocks, our toes began to go numb, our teeth rattled–but through it all I persisted and waited. The spectacle to come was worth all the hardships.

The soldiers, the officers, the colonels emerged, and arranged themselves in straight rows. The drill sergeant gave the signal and they marched back and forth through the square. It was a sight to behold. The military orchestra played, the drummers marching in front, beating their drums. The lead vocalist let out a protracted melody with a soldier's refrain and the whole company sang in response. For me it was a source of jubilation.

[Page 193]

I sang along and skipped along after them in time with the drumbeat. I accompanied the soldiers through the town and some of the way out of town until they went into their barracks. Only then–hungry and half-frozen–would I turn around and return home to have something to eat and regain my strength. I wouldn't have missed a military parade for anything in the world.

The epidemic that spread over the whole country touched the town of Augustow with its black wings. Terror seized everyone young and old: people were dying, cholera was running rampant through the town and people were dying. The afflicted would start to vomit, get diarrhea, stomach cramps–and fall like flies. This is what the adults were saying, and the children repeated the same words in horror, in fright.

We had to take precautions. I wasn't allowed to eat any raw food–no fruit, no vegetables. I wasn't allowed to drink water that hadn't been boiled first.

Fear hovered over the whole town, a fear with its own peculiar smell that tickled my nostrils: the smell of sawdust and carbolic acid. The cutters were awash with carbolic acid; it was poured on the toilets, on the floors, on the walls–carbolic acid everywhere.

My father was no longer the same person. He no longer sat in the next room writing sermons; no, he donned a strange smock, tied with a leather belt around the hips. He set off to the synagogue early in the mornings. I followed him from a discreet distance. A group of men were waiting for him in the synagogue. They were going from house to house with a bottle of alcohol and various utensils. But before they went to work they prayed quickly and recited a few psalms. They were going to visit the sick, to rub alcohol on them, and in this manner they saved many lives. They were all strong and tall, fearless in the face of the cholera. They were unflappable and indefatigable. My father would come home late, and he too would smell of carbolic acid.

By the market square, no more than a few paces from our house, stood a small shop. The entrance was behind a porch up a flight of steps. An old woman sold leather there to be made into boot soles, gaiters, horse collars and other things. On rare occasions her husband would also make an appearance there. He was an elderly Jew, a soifer. I knew him well, I would go into the shop, and peek in through the door at the back, stealing a glance into the living quarters behind, which consisted of a single

[Page 194]

room with a kitchen. The soifer would sit, wrapped in a tallis and tefillin, writing with a goose feather. He was in the process of writing on a Torah scroll, quite a contrast to my father who would jot down snippets of Torah on pages of white paper with a steel pen. The soifer wrote on yellow parchment and his handwritten was something entirely different.

He was an old, shrunken man, his face a collection of wrinkles bordered by a patchy beard. I knew that the soifer was a very pious Jew and that the work he did was holy; he wrote the Torah scrolls that were wrapped in a mantel and held in the Ark at the back of the synagogue to be taken out during prayer services and placed on lectern, and that people were called up to read from it. Afterwards the Torah scroll would be held aloft for all to see, before placing it, with great ceremony and respect, back into the Torah Ark. There it would remain, locked and secured with a poroykhes.[3] It does not stay there alone; there are other Torah scrolls in there, all decked in beautiful, embroidered mantles.

Torah scrolls just like these were written by the soifer Reb Zelig.

When the soifer fell ill I learned about it from conversations at home. The little shop would be closed. I would have loved to see what it looked like when someone came down with that curious illness, cholera. But my mother and Zelda[4] would not allow it. A few days later they took the soifer from his house and brought him to the cemetery. The old woman who used to stand in the shop wept aloud.

After they removed the soifer's body they burned the bed he had slept on, along with the straw mattress, pillows, blankets and everything else that had come into contact with his sickbed. But I went to have a look anyway; I was not able to get too close. I was surprised: “Why are they burning it all?” I asked an older boy who was standing nearby observing the curious scene. He informed me that cholera was such a contagious disease, that it even infected the bed linens.

I knew by then that in the synagogue yard–which was covered in fresh, green grass as good as the finest lawn, and which could be an excellent playground for me and my little friends–there was a shed which housed the stretcher and the ta'are board,[5] two things before which I and the other children trembled in fear, because they were connected to death and the dead. I also knew that there was an Angel of Death

[Page 195]

who went around armed with a sword. He had many eyes, and he took people's lives and one needed to watch out for him.

I never played in the synagogue courtyard. Not only was I afraid of the ta'are board and the stretcher, but I was terror-stricken by the synagogue itself. It was a huge building of stone and brick, with wide stairs leading into the antechamber. From the antechamber it was down another set of large stairs down into the cellar where the main part of the synagogue was. The synagogue was an intimidating place. At night the dead played inside. The old shammes–I knew him well–kept the synagogue locked, but naturally that did not deter the dead from coming to pray inside. Every morning the shammes would knock on the massive door with his heavy key and ask the dead to leave the premises. As he did so he would repeat three times: “Go to your rest!” Only once the ghosts had had time to leave would he dare to open the synagogue doors for dawn prayers.

I went into the synagogue with my father, Reb Yehuda Leyb, only for Yom Kippur. The rest of the year I followed my father into the prayer house. As he walked past the other people stood up. I enjoyed seeing them show honor to my father.

I went to the synagogue for evening Yom Kippur service arriving just before Kol Nidre. Before Kol Nidre my father, the rabbi, held a short sermon full of spiritual awakening. His call for repentance was met with lamentations. Above all, one could hear the sound of the women weeping and lamenting their past transgressions. There were many lamps, candles and candelabras burning. The synagogue was packed with people. It was so hot and suffocating that it was hard to breathe. The stone walls were sweating condensation. I alternated holding one cheek, then another, against the damp stone walls, in this way cooling them and helping me to catch my breath to avoid fainting.

We were all woken up by the alarm. But seeing as the fire was burning on the other side of town we calmed down and went back to sleep. I wanted to go and see the fire for myself, but I was not allowed. The fire burned the grain-merchant granaries on Zoyb Street. I rushed there first thing in the morning. I had missed the flames, but I was determined to see the ruins with my own eyes; there were still a few embers smoldering, while in some places there were only a few wisps of steam.

[Page 196]

Mountains of ruined grains lay piled up, alongside bricks from the broken foundations. I found it all so interesting.

The rabbi changed apartments again for the third time. Whenever the rabbi went to look at a new apartment he would test it out with his voice; if the acoustics were good, and his voice resounded well in the space, and the resonance was to his liking then he would give his approval and we would move in. Near the rabbi lived an old widow. She had two children. The youngest was only a year older than me. They went around in tattered clothes and were always hungry. I would run around with the youngest; we played together and whenever I had food I would share my last morsel with him. When I was having fun I would forget to eat and drink, and so I had no problem parting with the snacks Zelda had prepared for my playtime. I would spend the long warm summer days running around and would come home exhausted and fall asleep practically as soon as I crossed the threshold. Sleep was as sweet as paradise in those days, as delectable as the finest jams.

My mother, the Rebbetzin Khaye Esther Sore, would help the widow whenever she could: with hand-me-down clothing for the children, with food, but above all with credit. She vouched for the widow and arranged for her to buy a whole barrel of herring on credit. The widow would set herself up in the main square during market days selling the herring and paying back the Rebbetzin what she owed. The wholesaler, knowing full well that the Rebbetzin was doing a mitzvah in helping the widow provide for her children, played along by offering a lower price.

In this whole affair I acted as messenger: joyfully, fully aware that I was doing a good deed, I would go to tell Markus that my mother would guarantee the barrel of herring that the widow Rivke would buy from him on credit.

Markus was a Chasid, with a reputation as a learned man, and from a respectable family to boot. He had a well-stocked shop, with all manner of dried goods, smoked fish and barrels of herring.

With pleasure and a feeling of satisfaction in playing an important role in doing a good deed, I would take

[Page 197]

the grubby pouch full of five-kopeck pieces and coppers–which stank of herring–and bring them to Markus on the morning after market day.

My mother and father decided that it was time for me to learn in cheyder. As teacher they chose Chaim “Kukuriku.”[6] That's what they called the teacher for beginners. He had earned his nickname thanks to his hoarse voice as he was always coughing and clearing his throat and so the children had granted him this uncharitable moniker. Soon everyone in town called him this; most had forgotten his real surname, and those who knew it chose to ignore it.

Kukuriku had served a full term as a soldier: a strenuous discipline. He carried his discipline over from the barracks to the classroom. He would beat the children without mercy. He gave one child such a thrashing that he fell ill, languishing a few weeks before passing away. But these stories–and they were not just stories but genuine occurrences–did nothing to damage his reputation as a “pedagogue”–in fact, if anything, it had the opposite effect. He gained a reputation as an effective teacher. He was a very good teacher of Hebrew, and not bad at teaching Chumesh and Nevi'im. Even the fact that he beat the children–was there any other way to make those little devils learn after all? On Mount Sinai the Torah had also been received through violence, bending the mountain like a barrel: “Either you accept the Torah, or you will be buried here on this spot.”[7]

But the Rebbetzin was apprehensive: I was a weak child–one proper soldier's slap from Chaim Kukuriku and I was a goner. And so the rabbi called the teacher to him and, in my presence, told him, in the words of the angel to Abraham: “Do not lay a hand on the boy, or do anything to him;”[8] and if the teacher did not do as he was told my father told me to come straight home and tell him and I would be taken out of cheyder. The teacher was not to touch so much as a hair on my head.

Chaim Kukuriku understood that his reputation as a teacher would only rise with the news that the rabbi had entrusted him with the education of his son; it was a seal of approval for his style of teaching. He also understood what a disaster for his career it would be if the rabbi took his son out of his care. And so, with a heavy heart, he accepted the conditions and promised not to beat me, though in truth he could not imagine

[Page 198]

how it was possible to teach a boy without a few slaps, or at the very least the threat of them–how is it possible for a child to learn if the cane did not hang over his head? But that is how it had to be; he accepted the rabbi's conditions though he held them to be entirely nonsensical.

They prepared for me to join the cheyder. Zelda brought me. She held my hand and led me as far as the threshold, allowing me to cross over by myself to become a schoolboy independently of her.

I went inside and remained standing by the door. In front of me I saw the wrathful teacher, who was in the process of shouting, and a handful of children my age, as well as a few older than me, a mixture of boys and girls. I was dazzled by the noise and commotion.

The teacher's greeting was not especially friendly. He was disappointed that I had been brought by the maid and not by my mother, the Rebbetzin. He was standing beside the window. I did not want to take a seat between children I did not know, and then there was the racket which all but tore my ears off. I was afraid, a little Daniel in the lion's den.

I refused to stay if Zelda did not stay with me, and so she stayed. There was not enough space for both of us on the bench, and so the teacher's wife brought out two chairs just for us.

Zelda accompanied me to cheyder the whole week. During that first week the teacher taught me nothing. I sat there watching and listening to everything happening around me. Gradually I grew accustomed to my new environment, and I began to make friends with the other children in the cheyder and stopped being afraid of them.

I would stand in the corner of the room, watching the teacher, my whole body trembling, even though I knew that I was protected from his beatings. My teacher would obey the rabbi's wishes. Everyone had to obey my father, the rabbi of the whole town, for whom everyone stands when he enters the prayer house. And yet I trembled, because a teacher is someone to fear, and also someone to honor, or so my mother had told me, and Zelda too, and even my father the rabbi: You must hold your teacher as dear as your own father, because he teaches you Torah, God's Torah.

From the second week on the belfer[9] brought me to cheyder in the mornings and brought me back home in the evenings.

[Page 199]

The cheyder was located on a small side street not far from the edge of the town. On the other side of the street, heading westward, were various gardens, and a little further on was the bathhouse just on the outskirts of town, at the very edge of the world.

With yearning and desire I looked toward the bathhouse and over the roof of the bathhouse. At a slight remove from the bathhouse was already world's end. One time I approached the bathhouse, but as I got closer the edge of the world shifted further away, revealing a new expanse of space–I was afraid. Who knew what kinds of ferocious beasts were lurking out there, and maybe there were even serpents, which are much worse than beasts?

The cheyder was made up of one spacious room. The furniture consisted of several benches and a long table that stood in the center of the room; the table was surrounded on three sides by benches for the children, while at its head was a chair for the teacher. The teacher's apartment was made up of a kitchen and one other room where the teacher lived with his wife and two young daughters–one breastfeeding while the other crawled around–as well as three or four chickens.

The cheyder was not especially clean, but the other room was positively filthy. The stink of dirty diapers emanated from there along with the sound of crying children and clucking chickens.

The “modern” aspect of the cheyder was that the space was entirely dedicated to learning: the teacher and his wife did not sleep in that room. But all day the teacher's wife, their children, and the chickens, wandered back and forth through the cheyder, because their bedroom was too small for them. The cradle along with the bed, pillows, blankets, a few rickety chairs and a commode filled up that room until there was nowhere to move. There was one other noteworthy addition to the cheyder, and that was a portrait of the Tsar, which occupied pride of place on the western wall.

I was genuinely terrified by that portrait. The other pupils often talked about the Tsar. They regarded him with great awe, as someone who stood near the heavenly realm, operating with the approval of God himself. I imagined him to be a creature on a higher level than a mere human, more important even than a rabbi, he dwelled somewhere among the angels. The words “malekh” and “meylekh”– “angel” and “king”–sounded so similar, suggesting to me a link in their meaning as well.

The children would bring food from home to keep them going during the day, though we would return to our homes to eat a warm lunch. I was not much of an eater, and

[Page 200]

would take no more than the smallest snack to see me through the day.

For the most part the food was sliced bread rolls with butter which the children kept next to them on the benches. The dirt and the food attracted whole swarms of flies such that the buzzing rose above all other sounds. The lays laid siege upon the windows, doing acrobatics and other fly-exercises along the windowpanes.

The hours in cheyder were very long, from early morning until dusk. When boredom grew intolerable we would sneak out into the yard with the excuse of needing to go to the toilet. Instead we would stand in the outhouse, or between the blocks of firewood, trousers undone, talking. We were in no hurry to finish up and go back inside, but we could not linger for too long or else the teacher would come to see what we were doing and drag us back into the cheyder.

During the second term a whole gang of girls arrived in the cheyder, from the large, extended Keynanes family. Blonde girls with red cheeks, beautiful, pure, dressed up almost like dolls; that's how they appeared in my eyes. They would bring large, buttery cakes with them, and bottles of milk. Early in the morning they would start on their provisions, eating with appetite, not because they were hungry, more as a kind of vain bragging, to show that they were rich and could afford to have the very best.

I hated them on principle, and hated them especially for their ostentatious dressing up. My sister, Rokhl, who had now joined the same cheyder and sat in the beginners' section, had no love for them either. Fights often broke out between her and the Keynanes girls and I, naturally, always took my sister's side. The weapon of choice in these fights was not their hands–they were not strong after all–but their mouths. Verbal disputes and hurled curses. The most powerful weapon of all, in terms of destructive force, was the employment of nicknames.

It is interesting to note how the animosity that existed between the parents was carried over by the children.

A constant, endless conflict reigned between the Keynanes girls and my sister, while I, as her brother and protector, was always dragged into every verbal duel. As the principal combatants were girls it never came to thrown punches,

[Page 201]

though the mutual hatred burned all term with no sign of abating.

The Keynanes girls were fast learners, and they could already recite Hebrew loudly and clearly, with pleasant voices. I would have admired them if I could have forgiven their vain arrogance, their pride, their flouting of their fine clothes, their cambric dresses and delicate Ukrainian embroidery.

There was very limited time for playing, except between terms during the major holidays. During term we played mostly on Friday afternoons when we had time off from cheyder. Then we would play in one of the courtyards as far away from the watchful eyes of our parents as we could.

Like all the children my age I played “soldiers” and “court.” A thief or a bandit would be caught and would stand trial and be punished. It turned out I was a good palant[10] player, a past-time that several other children enjoyed.

The game consisted of placing two bricks on the ground, with a length of string between them. A board of wood, sharpened on both ends, would be placed on the bricks. The player would take a narrow, flat plank of wood and knock the sharpened board with it in such a way that it would fly into the air. Once airborne the player would give the board an almighty wallop, hurling it into the distance. We would measure the distance travelled by the board. Meanwhile the second player would try to catch the board with their bare hands and send it back. The closer it landed to the bricks the more points it was worth.

I also liked to go walking with Nisl, the son of Sheyne Yudis, over the fields, through undeveloped lots and unfenced yards collecting stones, which we would carry back to Sheyne Yudis's yard. For me it was just a game, a way of passing the time, without any other motivation, but that was not the case for Nisl. When Nisl had collected a good pile of stones he would sell them for a few kopecks to a man who would come with a wheelbarrow–once even with a horse and cart–to collect the stones. When I realized that my game had been debased by this transaction I was annoyed. I lost all interest in collecting and carrying stones; I stopped helping Nisl. I felt a natural antipathy to the whole business of buying and selling.

[Page 202]

I had a friend who lived on the other side of the park. His father had an iron workshop. The child had a tricycle–a contraption with one large wheel in front and two smaller wheels behind. He rode around on that tricycle as if it were a horse, all around the yard. He was a good friend and from time to time he let me have a go on his “iron horse.” I was in seventh heaven. Riding was such fun. I all but burst for joy. To this day I can't quite get my head around the idea that fate can gift little children with such intoxicating pleasures. Every Friday, as soon as school was over, I would run at full speed to my friend, in order to snatch a few minutes to ride on his tricycle.

On Saturday we would usually play at home. There wasn't much to be done in the yards. Most of the games we would want to play were forbidden on Shabbes, as they involved carrying things. It was forbidden to carry anything in our pockets, so the best was to just stay at home.

We played in the parlor, the largest, cleanest and most beautiful room in the whole house. It was rare that anyone would pass through to disturb us there. It was practically the “Holy of Holies” of the house. It stood empty almost all year round. Only the most honored guests would be entertained there. Large mirrors hung on the walls. The furniture consisted of a half dozen upholstered chairs, two sofas equipped with covers to protect them from the dust, a round table topped with a tablecloth; the windowsills were decorated with well-tended and healthy potted plants.

The children gathered there and–crowned a king, a Jewish king. Why did the Gentiles have a Tsar and the Jews had nothing? The Jews should have their own king, and his portrait should hang on the wall. So what if we were in Exile?

An armchair served as a lofty throne.

Who was chosen to be king? Moyshke, the youngest. But you couldn't have a king without a queen, so we made his youngest sister Masha into his queen. And why did we choose Moyshke of all people? There was a certain logic to it. He was the youngest and in that regard he was unsuited for any of the other roles which would have required more understanding, action, initiative and he was entirely unsuitable for them.

[Page 203]

To be a Tsar he didn't need to do anything, just sit on the throne with a swelled head like a turkey. That was the only thing he could do; he held court with great poise.

For whatever reason I was chosen to be the chief of the army which did not exist, so I had to play both chief and the whole army.

Even though there wasn't much to do in the game it amused us for the whole day. Everything we had to do, from guarding the throne to bowing before our great king, we did with great ceremony: we were in the presence of royalty.

I came home from cheyder late in the evening. It was already cold; the days were short, and the streets were covered in slush. We walked home together in a kind of procession, holding lit lamps made of paper, homemade. We children had ourselves folded the paper forming the skeleton of the lanterns. To make the paper transparent, so that the light would shine through to light up the way, we soaked it in fat or kerosene.

The others would walk me as far as the yard, and from there I had to run the short distance inside in darkness. A single lantern was no match for the darkness, barely making a dent in the pitch blackness. I missed the old days when the student from Yedwabne, a boy, would collect me and accompany me home. I arrived inside panting and half-alive.

No one paid any attention to me; it was not like usual when they showed interest in us children and Zelda would prepare me food right away.

I was surprised. I could feel tension in the room, an emotion was being choked back, but it was not sorrow, rather its opposite–a suppressed gaiety. They were overcome with joy, but were afraid to show it in case someone saw.

I have a sixth sense for these things, and I could feel that something important and good had happened.

What was it?

[Page 204]

My sister, Rokhl, who had stayed at home this term rather than going to cheyder with me, explained what was going on:

“Did you not hear? The Tsar has died.”

“How do you know that?”

“Father said.”

“Should we celebrate?”

“Of course, he was bad for the Jews.”

An hour before, the rabbi had paid a visit to the mayor. He was a Pole, a patriot, but his patriotism was something he hid under lock and key.

He entered with a feigned look of sorrow on his face:

“Our emperor is dead,” the mayor announced the news in a voice laden with suppressed joy and feigned sadness.

“We must declare tomorrow and the days that follow as days of mourning.”

The rabbi agreed that the fatherland had indeed suffered a great loss.

The rabbi, Reb Yehuda Leyb, was a double rabbi: a real rabbi and a state appointed “official” rabbi. Which meant that he held a small administrative office.

The Poles in town were happy, and they knew full well that the Jews were no less happy, but both groups were wary of expressing their joy in public: particularly they were afraid of the soldiers and the Russian officials garrisoned in the town.

I was overjoyed: I did not have to go to cheyder the next morning, and could avoid facing my arch-nemesis–my teacher.

Wouldn't it be great if a different nasty gentile–king or no king–died every day? I hated my teacher, but did not wish him death … it was forbidden to curse a fellow Jew, and certainly not a teacher, no matter how bad they were.

The rabbi soon informed all the townsfolk, all the gabbais from the synagogues and all the shammeses.

The next day candles burned in every prayer house. The rabbi announced that we should read Psalm 109.

All of the important people in town came down.

The large synagogue was packed. The rabbi declaimed the scripture himself, with a mournful, pious tone in his rich baritone voice: “Let his children be fatherless, and his wife–a widow. Let his children be continually vagabonds, and beg; let them seek their bread also out of their desolate places … Let there be none to extend mercy unto him: neither let there be any to favor his fatherless children … Because he remembered not to show mercy, but persecuted the poor and needy man…

[Page 205]

as he loved cursing, so let it come unto him: as he delighted not in blessing, so let it be far from him. As he clothed himself with cursing like as with his garment, so let it come into his bowels like water, and like oil into his bones. Let it be unto him as the garment which covers him, and for a girdle wherewith he is girded continually …”

The rabbi recited the whole psalm and the mayor all but dissolved in sorrow …

I began to see a new teacher, a Gemara teacher, an elderly Jew with a dignified face and a grey beard. He was a kind-hearted man, and a sickly man–he suffered from pains in his legs. His wife too was a courteous, refined woman who almost never showed her face in the cheyder. She sat in her room, or worked in the kitchen. The teacher had a son-in-law who lived with them. The young couple had their own alcove. The son-in-law would sit all day working, making leather goods; wallets, women's handbags and the like. His work was precise, pure and elegant. He did not have a “patent,” that is to say he had not paid the government for a work permit allowing him to earn a living for himself and his bride, the teacher's daughter. Police raids were quite frequent. The police would barge in, trying to catch him in the act. During such raids, the teacher would tremble like a leaf. The son-in-law would quickly hide the material he had been working on. There was not a lot to hide, and he would make himself scarce, escaping out the back window that opened out onto a yard. The searches and raids usually ended with a few carefully deposited coins in the pockets of the tax inspector and the police officer who accompanied him. The fear was considerable, but the teacher did not interrupt his lessons: he did not want to show that it had anything to do with him, to avoid being held responsible for the sins of his son-in-law.

During these raids, my heart all but fell out of my chest. My hatred of the police and the hated regime grew in my soul. Who did they think they were, tormenting my good, kindly teacher? Why did they want to scare him?

The love that a Jewish child usually feels for his spiritual father-figure, the one who teaches him Torah, Mitzvehs and good deeds, which I had not felt for my first teacher, I now gave two-fold–like a debt with interest–to my new teacher. I truly revered him.

[Page 206]

Nisl, Sheyne Yudis's boy, was also a pupil in the same cheyder. He was tall, three years older than me, and knew a lot less than I did. It was no wonder. Nisl never listened when the teacher explained the meaning of the words in the Mishnah or the Book of Isaiah. During lessons Nisl kept his hands down on the bench, fidgeting with something, hiding a treasure or a booklet of some sort. He had customers for such wares and was paid for them. He always had something he would rather be doing. Nisl was actually more a friend of Velfke,[11] though Velfke learned with a different teacher, one with a reputation as a scholar. He was dark-haired, tall, and thin with a short, trimmed beard, also a sickly man. His name was Reb Abba, but the pupils called him the “Straw Cossack.”

The cheyder shared a large corridor with the neighboring tailor. His name sounded a little strange to my ears: “Kushmender.” It's possible it was not a real name at all, but an epithet, containing a little “shmendrik”[12] within it. But I had no connection to the tailor and his name, or nickname would not have interested me in the slightest if he hadn't had a son who learned in the same cheyder as me.

He was an only child, about two years older than me. The boy was not the brightest, but his father, the tailor, believed that Torah was something that could be hammered into you, or forced down your throat like a bitter medicine. He genuinely wanted to make a scholar of his pride and joy. Because he was a high-class tailor, who earned a good living and could afford the fees he enrolled his only son in a good cheyder, approaching my teacher and offering to make it worth his while. He asked my teacher to pay special attention to his son, and in return he would earn an extra bonus on top of the usual fees.

In simpler terms, he had given the teacher to understand that he should not hold back, and could “skin the boy alive” as long as he got results.

The teacher had a section in his cheyder where he taught both Gemara and the works of the latter prophets as well as the Ketuvim. The teacher, unable to refuse his neighbor Kushmender's offer,

[Page 207]

put the boy in this section, which was much too advanced for him with his limited capacities in Hebrew.

The whole week learning in cheyder went according to plan. But on Friday when it came to repeating, that is to say being examined, everything fell apart. The Kushmender boy did not know the meanings of the words from the chapter we'd just finished learning. He could read the lines without difficulty, but when it came to explaining the sentence he was at a loss. The examination began first thing in the morning, and continued into the afternoon when the school day came to an end. For every wrongly explained word there was a slap, resounding slaps.

The beating could not change anything; the teacher's slaps were in vain. It made about as much sense as whipping the benches, or trying to beat milk out of a billy goat. With my instinct for pedagogy I could see it wasn't a matter of the boy not wanting to learn, it was simply that with his soft teeth he could not bite into the tough complexity of the prophets' speech which was aimed at a more sophisticated audience, with a firmer grasp of Hebrew. The expressions were too beautiful, too embellished, too lofty. The young Kushmender had to learn the latter prophets, had to struggle his way through them.

It's possible the teacher knew all this, but renouncing the juicy financial carrot, especially in his financial position, was not an option. Abandoning the boy entirely to his ignorance and incompetence would have been inappropriate: he was paid double for teaching him and goading him on. It would not do to spare the rod, so he continued to whip him in the hope that perhaps a miracle would occur and the colt would be able to pull the overloaded wagon after all. Giving the colt a smaller load, that is to say, teaching the boy easier material was not something he was prepared to do, not just because he did not have the time to teach a separate course, but also because it would undermine his position in the hierarchy of teaching: a Gemara teacher has no desire to become a Chumesh teacher, that would be a step down. Should he lower himself all for a single peasant? There was only one solution: whipping and beating–he was being paid to break bones after all.

I was a soft-hearted boy. I could not bear to watch the execution. On Fridays, when the teacher was busy with Kushmender's boy I would go out to the toilet and loiter there for as long as possible.

The teacher lost a lot of respect in my eyes from playing the role of a violent man; it was a role that did not suit him.

[Page 208]

The cheyder had a supplementary teacher, and that was the Russian teacher. What was his name? The children did not call him by his name. He was a short man, but as stout as a barrel, almost broader than he was tall, as the expression goes. The boys called him Bulke[13] –bread roll. His job was to come into class for an hour or two to teach the boys how to read and write in Russian, along with a little arithmetic.

Both subjects seemed easy to me. Russian was not an unfamiliar language for me. I could understand the Gentiles, the laborers in my grandfather's yard, and they spoke a language that was very similar to the literary Russian that Bulke taught me. But I truly adored arithmetic. I quickly mastered the multiplication tables which went up as far as a hundred. The numbers were laid out in such a way that you could find the correct answer without having to calculate. All you had to go was to find the numbers in the horizontal and vertical bars and in the place where the lines converged there would be the answer. When I was going to bed I would set up a chair next to my bed, and on the seat I would read arithmetic problems, exercises from a book called Zadatshnik[14] (problems).

Two years before I did not yet go to cheyder but I would sometimes meet Velfke when he came out of Abba the straw Cossack's cheyder. I would bump into Velfke's friends as they were off to eat lunch.

“Where is my brother?”

“Bulke kept him behind, making him miss lunch as a punishment.

“Really?” I was surprised.

The boys told me to go inside where Bulke was currently teaching another class, and ask the teacher: “Bulke, why don't you let my brother Velfke go to eat?” That would surely help, they said.

What one won't do for one's own brother! I did not know that Bulke was a nickname and so I did exactly as the boys had suggested.

I went inside and addressed the teacher with my question, calling him “Bulke.”

The teacher turned as red as a beet. The class almost choked with laughter. The pupils had gotten revenge against their hated teacher. I soon realized that I had made a terrible mistake,

[Page 209]

though I had no way of knowing what I had done wrong. In fright I ran out of the cheyder and rushed home.

An hour later I see Bulke is there. He denounced me to my father: what was the meaning of me humiliating him in front of his whole class?

My father did not reprimand me: he was sure that I had acted in complete innocence–as indeed was the case–but when I discovered what I had done, in my foolishness, I felt ashamed. I humiliated a teacher, a person second only to a rabbi in prestige.

After this error I became more cautious. I began to realize that it was better not to do everything that the older boys told me to do.

Velfke went off with the widow's son, who was the same age as him–while I tagged along like a calf following a cow–toward the river, or more accurately, to the bridge which was suspended over the River Netta. This was where the river met the canal. On one side of the bridge the river was level with the earth, and on the other side it poured down into a deep valley, a drop of perhaps a hundred feet. If it wasn't for the bridge and the lock there would be quite a waterfall there. When barges approached the bridge from the river, the canal would be filled with water until the water was on the same level as the river. The barge would be let in and then the water would be allowed to gradually flow back out until it was now level with the canal in the valley. The lock gates could then be opened, allowing the barge to continue on its journey.

I wasn't much of an eater. It was only with much cajoling that you could even get me to drink half a glass of milk before setting off for cheyder in the morning.

To stop me from fainting with hunger I was sometimes given a whole five-kopeck piece, sometimes only one, to buy something to eat.

I would set off in the mornings without any baggage. I did not need to carry any books with me: the Siddur, Tanakh and Gemara were waiting for me in cheyder tucked away in the desk drawer.

[Page 210]

It was a fine, sunny market day. There were countless wagons parked on the market square. The horses were unhitched, the wagon shafts raised. They looked like dried, branchless trees. The market was abustle with Jews and Gentiles alike. With difficulty I picked my way through the heaving throng, the human sea.

I hold the copper coin tightly in the palm of my hand so as not to drop it and lose it in the bustle. I think about what I'll buy with it, deciding this time not to buy any sweets but some proper food.

I walk past a line of tables, old Jewish women hawking their wares: a veritable cornucopia. I stop, and consider the sweets, the fruit, the various berries. It's hard to resist these distractions and stick to my plan. I hesitate: what should I choose? Should I give in to temptation and buy some sweets? No, I shall not give in. My gaze falls on the cheeses. A bargain: a penny a piece. I know my way around the prices. I'm a seasoned buyer after all; I won't pass up a bargain like this–I buy a piece of cheese.

In cheyder I show my classmates the piece of merchandise I purchased for next to nothing. Everyone admires my shrewd acquisition. Several boys ask me where I bought it, as they too would like to get in on the action. But the time it would take to leave the cheyder, go to the market, and come back, was not a luxury they had. What's more they could not be sure that the cheese had not all been sold out by now. It was a market after all, with so many customers coming from all over to shop there.

I eat my cheese. Really I only tasted it. I could not eat it. After the first bite I already felt full. I looked at the cheese in my hand and thought: What should I do with this? I can't eat any more. There's no point in taking it back home with me after class. There's no shortage of food in the house. And my mother would surely shout at me for buying food without eating it. Should I throw it away? It is a sin to squander God's bounty. There was only one way out: share it with my classmates. I divided the cheese into four equal parts. I give the first piece to Nisl. All four friends eat their cheese with relish, promising me that when they buy cheese they will share a piece with me. Measure for measure.

At that time my father had an appointment to visit the military doctor. My father, like all rabbis in the towns and villages, dedicated a lot of his time and energy, among other things, to

[Page 211]

attempting to free bright young boys from the clutches of the army. He could not abide if a young man, a potential scholar, was taken away from his Torah study to “serve the Tsar” and waste three years of his life on military service. Snatching someone back once he was already in uniform, already conscripted, had one great advantage: one boy's escape would not put another Jew at risk. Every town had to provide a particular quota of recruits. If you succeeded in exempting one Jewish boy by means of bribing a doctor or an official, another Jewish boy would have to take his place. And so a favor for one, would be a dirty deed for another. Rich families freed their sons by offering bribes. Poor scholars were freed in the same way. Pious Jews would pool their money to find the necessary funds, and so the holes in the quota were filled by poor boys and ignoramuses.

But my father did things differently: it is not good to do a kindness at someone else's expense. What he liked to do was take a scholar out of the regiment; that was without doubt a worthy thing. No one, or at least no Jewish young man, suffered because of it. This form of ransom my father performed with his whole heart and soul. Whatever risks he took he justified to himself with the thought that the townsfolk would never allow him to be arrested and sentenced to hard labor in Siberia.

The process was a simple one. The recruit feigns an illness and asks the military doctor to examine him. The chief-doctor would receive a bribe and would confirm that the patient was ill … the wording the rabbi, Reb Yehuda Leyb, used in such cases was precise and simple:

“Please, doctor, please help the patient in whatever way you can within the limits of the law (v predelakh zakona).”[15] But both the limits and the law were elastic; they could be stretched like rubber if it was to the doctor's advantage.

The meetings between the rabbi and the regiment's chief-doctor always took place in secret, late at night, in the doctor's home. Naturally, it was always better when there was some pretext for the late-night visit. My illness served as such an excuse. The military doctor was considered a good healer, though civilian patients in town rarely called for him, and it is possible he would not have answered if they did.

Reb Yehuda Leyb brought me, his son, with him to the doctor's house. Even though I was with my father I still felt scared

[Page 212]

when I stepped over the threshold into the doctor's richly furnished parlor, where my father left me to speak to the doctor in private. The parlor was a sight to behold. It was unquestionably more beautiful than the room in which we had crowned Moyshke as a king. Even Dr. Goldberg's apartment paled in comparison to this spacious extravagance. There were such large mirrors hanging on the walls that at first glance I thought there was a second room behind them. I was overwhelmed by the splendor and decorations that I was literally afraid to budge from the chair in which my father had told me to sit. The carpets on the floor were so thick and soft that I had not heard my own footsteps as I came into the room, and this only served to intensify my anxiety.

1896. The rabbi's house was engulfed in deep, heartfelt sorrow when the news arrived that Reb Yitskhok Elkhanon Spektor, the rabbi of Kovno, had died. I saw my father weep warm tears, something I had only ever observed on the eve of Yom Kippur as he blessed the children. My mother was also in tears as though it had been a family member who had died.

I knew that Reb Yitskhok Elkhanon had been a great scholar, a sort of general Jewish father figure. Mt father, Reb Yehuda Leyb, had gone to Kovno to visit Reb Yitskhok Elkhanon and when he returned he talked a lot about him, and about the hearty welcome he had received there.

A few years before there had been a drought, almost leading to a famine; by the time Passover came around the poor people had nothing to eat, and did not have enough matzo.

In our house there had never been a shortage of matzo. My grandfather, Reb Sender, sent us matzo flour every year, as well as matzo farfel[16] and three pounds of shmura matzo. Reb Sender himself supervised the wheat as it was harvested, bound and dried, then ground and baked. We had more than enough matzo. We shared our shmura matzo with whichever townsfolk asked for some, or even with those who did not ask outright, but sent their holiday wishes in the form of money, wine or cakes. We would send some shmura matzo back with the same messenger, and even after all this sharing we still had enough matzo left over for the children to eat all year.

[Page 213]

But the poor people in town did not have any food, that's what I heard at home. My father put his head down, thought long and hard, consulted scripture, and eventually issued a rabbinical decree permitting maize flour and peas.

In Sheyne Yudis's house they rejoiced when they heard news of the decree. They had a granary full of maize which they had amassed hoping to sell it at high prices and make a good profit.

But Reb Yehuda Leyb did not want to stand alone and take sole responsibility for the decree; and so he sent word to Reb Yitskhok Elkhanon asking for his opinion and received word that he approved the plan.

The answer was considered an important event in our household. Reb Yitskhok Elkhanon had said very complimentary things in his letter about Reb Yehuda Leyb's learning, expertise and shrewdness, causing a significant boost to the rabbi's prestige in town, to the annoyance of his enemies. Reb Yitskhok Elkhanon's letter was shown to all the scholars and important townsfolk. I also saw the letter. I was surprised to see such bad handwriting from such an eminent scholar–instead of letters it was scratchings and scribbles. I had good handwriting; Khayim Kukuriku was good at teaching handwriting and so my grandparents never tired of praising the letters I sent them twice a year for Pesach and Rosh Hashanah–letters actually written by my mother, but which I copied out by hand. I believed that a scholar should also know how to write beautifully.

In Augustow there was stationed, in the barrack built for that purpose, a large garrison, a division comprising four regiments.

There were quite a large number of Jewish soldiers in the garrison, and they were invited as guests to celebrate Shabbes and Yom Kippur. Others were invited to the well-off Jewish homes. There was a story going around: during a party in one of the houses of the shveydaks, a soldier had taken out a ring and put it on the finger of a girl of marriageable age, and uttered the magic words: “Behold, you are consecrated to me with this ring according to the law of Moses and Israel,” with several of his soldier friends as witnesses. A “shveydak” was someone who went off to Sweden for several months a year to peddle. There were several such families in Augustow, and all of them were quite well off financially.

[Page 214]

The town was turned topsy turvy. Everyone was talking about the incident. The girl's mother wailed and moaned; her father, the shveydak, was away on business. But word was sent to him and he came rushing back from Sweden without delay. They were not in favor of the match. What was to be done? They came to the rabbi to save them from their predicament, from the shame and humiliation. The girl was an only child and the soldier, a crude, simple lad, from a humble family in Odessa.

The scandal had the whole town abuzz. People were afraid to let Jewish soldiers into the houses where there were grown daughters.

I knew all the details of the case. I was proud of the knowledge that only my father could rectify the situation.

They offered the soldier money if he would agree to divorce the girl. He rejected the offer. If he offered her a divorce she would of course have the status of divorcée, and what boy from a respectable family would want to marry a divorcée? She would have to, God forbid, sit it out until her hair turned gray, or else marry a divorced man, or a widower. In short the misfortune was considerable, and the shame was no smaller.

Only one person could save them and that was the rabbi, the local rabbinical authority.

My father locked himself away in his rabbinical court, consulting a great many books and engaged in correspondence with other rabbis. In the end my father annulled the marriage, voiding the whole thing by invalidating the witnesses. They had been seen smoking on Shabbes, that is to say, they had publicly desecrated the holy Shabbes; they had eaten unkosher food at the barracks, and were generally debauched youths.

But it was the same as before: the rabbi did not want to rely on his own authority alone and so he again wrote to Reb Yitskhok Elkhanon explaining his judgement. And again a response arrived addressed to the rabbi with salutations of respect: the letter was addressed to Harov Hagoen H”G, the latter part an acronym of HaGodl.[17] The acronym made it a little less meaningful than if it were written out in full, nevertheless, to be called a “great genius” was a signal that Reb Yitskhok Elkhanon wished to support and protect the young Reb Yehuda Leyb by lending his full approval.

Young as I was, I was finding my bearings in the rabbinical hierarchy.

In short, Reb Yitskhok Elkhanon counted as practically a member of the family, a kind of spiritual grandfather, and I mourned his passing with great sadness. Naturally, I went to grieve

[Page 215]

in the synagogue to hear how my father would eulogize the great man. The synagogue was packed. The women's synagogue too was full. Not just women, but young girls too came. Reb Yehuda Leyb performed the funeral oration; the congregation wept, the women lamented and I with them, after which I felt purified, like a blue sky after the rain.

I was visiting my grandfather's house.

A young man appeared. He had brought a letter from my mother. He had come all the way from Augustow.

My grandmother was distracted and occupied: how would she cope with so many things to organize, there were only a few hours left before Shabbes would begin.

“Get out of here, what are you imagining?” She rubbed her hands, wiped them without a towel and donned her floral headscarf.

“I'm not imagining anything. He's standing outside on the porch.”

My grandmother followed me.

The young man handed over the letter.

I read it for my grandmother.

The letter was brief. Clearly written in a hurry. The letter said they were preparing to leave Augustow and move to Ostrow in Lomza Province. It was a big city and also an important rabbinical office.

My father brought me with him to Ostrow.

I saw new kinds of Jews. They were nothing like the ones I knew in Augustow; they spoke differently, they dressed differently. If my father was their rabbi then that must mean they were true Jews, genuine Jews, but in my eyes they still seemed a little strange. They were so shabby, with wild, unkempt beards and long peyes, and they were all muddy, dusty, dirty.

But curiously, from what I could see my father was fond of those strange Jews. They were always hanging around our house, coming and going. They never left the door closed. By all appearances they needed my father all the time, needed his

[Page 216]

advice. They were very pious Jews, so said my mother, and that's why they liked my father. But I didn't like them at all. How could I be expected to like them when they didn't like me? They looked at me askance, cut me with their eyes and call me a “daytsh.”[18]

I can't begin to imagine how I, a Jewish boy from Michaliszki via Augustow could be a daytsh all of a sudden; when you're born Jewish in a rabbi's household can you be any different? How does that work? I don't know how they can come up with such a strange accusation.

I go out in the street and the boys of my age avoid me, look at me like I'm a freak. They wore long caftans; the coattails tangling between their legs–surely an impediment to walking quickly. On their heads they wear such strangely shaped hats. I feel very uncomfortable in the streets. I prefer to sit at home away from watchful eyes. I'm ashamed of my attire.

My mother sent for a tailor. He took my measurements and in a few days' time I would have a long caftan like the others. I don't want to be so different from everyone else that they point their fingers at me. I also want to let my side locks grow so that they'll stop looking at me like I'm a scarecrow.

I was now all fitted out as was expected of me. I wore a long tales-kotn, a long caftan and a strange hat. I look at myself in the mirror–I can barely recognize myself. I think: I'm not the only one who has changed; my elder brother Velfke has also changed. The sisters have it easy, they have remained the same.

Augustow had quite a lot of Maskilim. There was a Hebrew and Yiddish library. The town even boasted two writers. One, named Frenkel, was a shopkeeper with a dry-goods store with his seat on the Eastern wall.[19] He published a long multi-stanza poem in Hebrew, in which he made fun of a fanatical rabbi who was splitting hairs about the line in the Gemara: “if a man falls from a roof and, in falling, inserts himself into a woman …”[20] The second writer, Shperling, was a helper of the state appointed rabbi, looked after the books of births, deaths, marriages, circumcisions, divorces etc., and had translated Jules Verne's (1828–1905) fantasy Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea from French to Hebrew, in which the author predicted the invention of an underwater ship.

Translator's Footnotes:

|

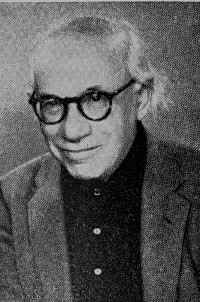

Abba Gordin was born in 1887. His father, Reb Yehuda Leyb, was a famous rabbi, a scholar of Talmud and Torah, as well as a Maskil.

In 1905–1906 Abba took part in the Russian Revolution and was arrested. In 1908 he founded (along with his brother V. Gordin) a kheyder mesukn, modernized religious school, in Smorgon, where he conducted interesting pedagogical experiments. In 1917 he took part in the October Revolution in Moscow where he was seriously wounded. He edited a daily newspaper Anarkhia (in Russian), battling Bolshevism. He was sentenced to death by the Cheka. Lenin pardoned him an hour before his scheduled execution. He left Russia illegally. Through Manchuria, China, and Japan he made his way to the United States in 1926.

He wrote in Hebrew, Yiddish, English, and Russian. He contributed to numerous newspapers, including; Yidisher Kemfer, Tsukunft, HaDoar, Mabua, Megillot, Sefer Hashana, Reflex (English), and Liberation (Russian) and between 1948–1950 the quarterly periodical Problems (English).

His works: The Children's Organizer, Game Album, Theatrical Garden, Youth (drama and verse), The Book of the Exile, Yiddish Grammar: A System of Material and Relative Naturalism (Russian), The Imitative Rational Method (Russian) (these later in collaboration with his brother V. Gordin), The Message of Transcomprehension (poem, Russian), Anarchy of the Spirit, Egotism (poems), Interindividualism, two volumes (Russian), Communism Unmasked (English), Jewish Ethics, The Basic Principles of Judaism, Women and the Bible, The Morality of Jewish Life, Social Superstition and Critique, The Foundations of Society, Memoirs and Musings, two volumes, Thirty Years of Jewish life in Poland-Lithuania, The Struggle for Freedom, Thinkers and Poets: Essays, Jewish Life in America, Sh. Yanovski (biography), Moses (historical novel).

At the end of 1958 he settled in Israel. Edited a bimonthly periodical Problemot–Problemen (Hebrew/Yiddish). Problems of the Society, The Maharal from Prague, The Ar'I, Rashi. He died at the age of 77 on August 21, 1964.

by Eliezer Aronovski

When Borekh Beyle-Dobes walked across the street, from afar one could mistake him for a man without a head. His neck was bent from spending night and day hunched over the holy books. His head merged with his body, as though the Torah had drawn it downwards towards its light as sunlight draws plants towards the sun.

The burden of having to earn a living and provide for their four young children, fell upon the man's wife, Beyle-Dode. She was an efficient woman: healthy and solidly built, she ran the bakery. When the children were grown they began to help her with the work. Their baked goods had a reputation, and they made a good living. Their household was one of small-town wealthy bourgeoisie.

The three sisters looked like well-baked bread rolls with tanned cheeks. Two of them had chestnut hair, while the third was a brunette with eyes like black lumps of coal that had been driven into the dough, never to be removed. A fire always burned in those eyes, beautifying her face and hiding her flaws. She had one crippled leg. With her gaze she compelled everyone to look her straight in the eye and not at her limping.

It was rare to see Reb Borekh at home. His natural habitat was the prayer house. His entrance always brought with it a change of atmosphere; like a message from another world–from the world of Torah and holiness; of awe and trembling, of mitzvot and good deeds. He would greet people with a laborious turn of the head, revealing his gentle, sky-blue eyes. When someone visited his house as a guest he would treat the occasion with a detached solemnity, as though he were not the host, the head of the household, but a messenger for Him that feeds and nourishes all creatures and people in the world, who gives everything their daily bread.

[Page 219]

One could say that he had mixed blessings from his children. His eldest daughter, Khave, who always looked like a Shabbes challah–straight from the oven, brown and fresh, just asking to have a brokhe said over her–became a widow quite young. Her husband, a rabbi, died a few years after the wedding, without leaving a child behind. She moved back in with her parents.

The second daughter, Khane, never had any luck with betrothals. Perhaps her pale face, half-baked, as though the flames of the oven had sapped the blood from it, and her sour smile, as though smeared in lemon juice, had repelled any would be matches. For all that her body was slim, flexible, shapely–a flowery posterior. She was a kind girl too, one in a million.

She did find a husband though, in the end, admittedly a little late perhaps. He was a yeshiva student, Reb Khayim-Zorekh they called him. He possessed not a thing in the world, save perhaps destitution itself.

He was welcomed into such a bourgeois home–cookies and cakes on weekdays; white challah, fresh every morning; crystal glassware for tea and mealtimes fit for the Tsar. How could one resist a home like that?

He had no need to worry about making a livelihood, he could sit like his father-in-law, studying the Torah, and to top it all off he received a dowry of several thousand dollars. He was no oil painting himself: a redhead, with a freckled face, like a cookie sprinkled with cinnamon. His eyes were dull and watery, topped with sparse eyebrows. The marriage was agreed upon.

Several months after the wedding he was hardly recognizable. He had filled out, put on weight, like a swollen tire. His eyes were smaller and deeper, squinting; his cheeks jutted out, his face wide and round like a rose with its kernel removed–just two eyes, still immature, remained.

Several years after the wedding and the only path he knew was the one leading from the house to the synagogue and the synagogue back to the house.

He sat and studied alone–without great desire. Alone, in solitude, benches and lecterns, in wooden silence the whole day long. His voice was lost in the void, like water poured into a leaky bucket …

In the yeshiva his voice had blended with a dozen other voices forming a song of praise; but here it was a lone voice in the desert. His only comfort was that his wife took good care of him, and he thanked God for his marriage.

[Page 220]

Time marched on and they began to search for a match for Rivke. True, she was crippled, and few cripples could hope to marry in keeping with their station … but a more pressing concern was where to put the son-in-law? Two sons-in-law in one house is like two cats in one sack. They had to find a way to get Khayim-Zorekh to go out into the world by himself; there was a whole world of Jewish businessmen out there, why could he not become one of them? They began to plant the idea, gradually, in his mind that he should continue to study as he did now, but only a few hours a week, and during the week he should go out and try to earn a few dollars as most people do it.

When Poland regained its independence as a state, hundreds of Poles came from America to settle in the surrounding towns and villages and from them one could always earn a little money. If the sum is small he can sell here to the local moneylenders, and if it's a larger sum, it would be worth his while traveling to Warsaw and getting 20–30 points more.

Khayim-Zorekh ate his breakfast, said his prayers, donned his coat and strode out the front door right into the market.

In the first moment he was lost. It had been years since he even stepped foot in a market. The shouting and the bustle, the noise and commotion seemed deafening to him. He stumbled his way through, around the wagons. A stallion let out a neigh at the highest octave, as though laughing at everything and everyone. Pigs squealed, tied up in wagons; hens, ducks and geese attempted to shout over the humans at their stands hawking their wares. With difficulty he found his way out from amid the wagons and back onto the sidewalk. He walked around, eyes peeled, searching for an American Pole, but could not find one for love nor money. He looked out for American shoes–an unmistakable hallmark of a returned Pole in those times–but there was neither sight nor sound of any. There was one man who looked like a nobleman and as he circled the perimeter of the market, every quarter of an hour, he looked him right in the face but could not ascertain if he was an American or not. He felt the man beckoning him with his gaze, with a welcoming demeanor. Several times he was on the verge of asking him if he had dollars for sale, but each time he lost his nerve and continued on his way. But how long can someone roam the streets concluding some business? What would they think of him at home? They would surely laugh at him, saying he was a total failure … how would that look if, after a whole day traipsing around the market, he came home saying he had not found a single American?

Thinking this he noticed that the nobleman was once again standing near him

[Page 221]

as though he were waiting to be called. He plucked up his courage and asked him: “Mocię macie talarow przedać?”[1]

He responded with a sly expression and nodded, yes. They went together into a nearby yard, behind a gate, and negotiated. The nobleman produced a twenty-dollar bill. Khayim-Zorekh touched it and scrutinized it from all angles to make sure it was not a forgery. He paid in zlotys and the two men re-emerged out onto the street. The nobleman stood still for a moment, and then asked Khayim-Zorekh to come with him. At first Khayim-Zorekh had no idea what was happening; he thought perhaps he was taking him to sell him more dollars. But when the man produced his ID, identifying himself as an undercover policeman, Khayim-Zorekh went weak at the knees. He began to tremble and begged him, half in Polish, half in Yiddish, to let him go.

The policeman choked with laughter at his bad Polish, and led him into the police station like a hardened criminal.

“I've got a new moneychanger for us today!” the policeman announced with triumphant pride.

Across from them, sitting at a desk, was a flaxen-haired sergeant who regarded him with an expression as though all the world belonged to him. From the wall, a portrait of the “old man” Pilsudski, looked down at him alongside a second image–the dead chicken[2]–the emblem and symbol of Polish independence …

The two men looked at Reb Khayim-Zorekh with disdain for the crime of dealing in foreign currency …

He attempted to explain, with gestures and grimaces more than with words, that he was no moneychanger, but that his sister was traveling to America and he wanted to give her some dollars.

They mocked him even more:

“Żydowski[3] brains … they have an answer for everything …”

Khayim-Zorekh sat frozen still on a chair in the corner. If he could have, he would have taken himself and torn himself apart, anything to avoid the shame that of all the thousand goyim wandering around the market he had to choose the undercover policeman!

Khane, his wife, began to worry about him … he should have been home from the market long ago. Her heart told her something was not right … she sent out her brother Ruven to go to the market and find out what was happening.

It did not take long. The Jewish shopkeepers told him

[Page 222]

that they had seen his brother-in-law walking with the police. Ruven went to the police station and found Khayim-Zorekh sitting there, pale and listless, looking like death warmed over.

After meeting with one of the fixers who was connected to the police they added another twenty to the twenty dollars and Khayim-Zorekh was free to go.

Khayim-Zorekh did not have a bite to eat that day, only a glass of tea with a slice of lemon. His blood was boiling, his face was aflame: his freckles seemed to merge together into one big fiery blotch. One could barely see his pained, tear-filled eyes.

Dear Khane, that kindly soul, his wife, comforted him as one consoles a sick child, caressing and stroking him, attempting to calm him down.

“It will never happen again,” she whispered in a motherly tone. “Your place is in the prayer house. I will go out and work for you, like my mother. I'll find some business to do and you'll be free to sit and study. That is my father's path and that will be your path. How had I not realized it sooner? Where was my head that I sent you off into the market? Well, what's done is done. It'll never happen again!”

Her words, like the cooing of a quiet dove, calmed his nerves and settled his troubled spirit. The evening sun shining in through the window encouraged him. It was time for afternoon prayers. He got up, said good day, and went out the back door to go to the synagogue.

Khane followed his progress through the window with pensive, pain-filled eyes. The hidden light of a pure soul radiated from her entire being, breathing sanctity and wisdom. Her lips trembled as though she were kissing his every footstep as he neared the prayer house, on his path–the path of the eternal Jew.

Translator's Footnotes:

Motinke the Sweet is one of the sons from the Kurik family. The Kurik family is a large, extended family of gardeners. Uncomplicated, healthy people, with wide shoulders and ruddy rustic faces. Most of them were blond with freckles

[Page 223]

and they walked with heavy, steady gaits atop solidly built legs.

They always carried with them the faint odor of the fields, of the gardens and orchards. In the springtime they plowed, tilled, and sowed. They watered the plots, plucked and tore out every weed, pampered every new shoot, every bud, until the plots were teeming in their full ripeness, overflowing with green.

The garden always followed them into the house, on the bare feet of the women, and on the boots of the men, together with the carrots, radishes, cucumbers and potatoes which lay in piles by the table, next to the chairs, in the corners, under the beds, along with clumps of the rich, brown earth itself, as though the garden had moved into the house to live with them.

Mottinke the Sweet was brown haired and of medium height. He looked nothing like his brothers, who were all blond, looking more like his two sisters who were both brunettes.

Mottinke found a girl who resembled himself, a dark-haired, plump girl whom he married and who bore him a daughter nine months after the wedding.

In addition to working in the gardens he also opened a fruit shop. In the summer, his shop also served cold glasses of soda water. In the early years his wife ran the shop and later new employees arrived: his own daughters. With God's grace his wife bore a new child almost every year, and every child, as if to spite their wish for a son, was a girl. Nonetheless their daughters were a source of pride: each was more striking than the last: black eyes, pitch black hair, just as Jewish children should be.