|

|

|

[Page 85]

In the Displaced Persons Center of Stuttgart

Convalescence in a Castle

After seven weeks under the beneficial care of the French liberators in Neuenburg, the survivors of the Vaihingen concentration camp were taken to the U.S. Zone of Occupation in Germany. Chaplain Haselkorn was instrumental in securing Schloss Langenzelle, an ideally located place in the country, for their convalescence.

By then many of the liberated Radomers felt strong enough to set out in search of their families. Those who remained in Langenzelle Castle attempted to organize their daily lives. There was no food problem for the Americans supplied them adequately. A committee was selected to care for the just distribution of American supplies, to maintain order and discipline, and to introduce some recreation and cultural activity. Most of the men took advantage of the Hebrew and English courses; some were attracted by the swimming and boating facilities at the nearby lake.

Many high-ranking officials and guests from the United States visited the castle and expressed their satisfaction at the progress made by the camp survivors towards a new life. Among the visitors were the Jewish leaders Dr. Nahum Goldman, Dr. Israel Goldstein, Moshe Sharett, as well as Jewish Brigade officers and soldiers. There was also Earl G. Harrison, special envoy from President Truman.

Radomers liberated from other camps began to arrive at Schloss Langenzelle to join their relatives and friends. Many separated couples were joyfully reunited thee. In a short time the quarters became overcrowded, and, alas, unsuited for family life.

The American officers in charge of the group, specifically Miss Ostrey of the UNRRA and Mr. Hatler of the military government, showed a deep concern for the Jews and did their utmost to make them as comfortable as possible. Within a short period of time they secured modern apartment buildings in Stuttgart with all conveniences and essential items of furniture.

“Radomer Center”

On August 25, 1945, the liberated Jews were transferred from Langenzelle to their new location in Stuttgart. Jews liberated from camps in Germany, Austria, and Hungary heard about the unusual comforts provided by the UNRRA in Stuttgart and flocked daily to the center office for registration. After some time, the center population reached about two thousand men, women and children. The majority, however, were people formerly from Radom, and thus the D.P. camp in Stuttgart became known as the “Radomer Center.”

The center was administered by the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Agency. Harry Lerner of Washington, D.C. was the first UNRRA Director of the camp, followed by Louis Levitan of Detroit, Mich. Both showed a great understanding of the unique problems of Nazi-camp survivors on German soil; they were instrumental in making Stuttgart a model center. Mr. Levitan later married Miss Mary Litwak from Radom and thus became “integrated” with the family of Radomers. He is now actively working in conjunction with Radomer organizations in the United States. Mr. Abram Goldberg from Radom was deputy director under both Mr. Lerner and Mr. Levitan.

One of the main tasks of the UNRRA was to supply the inhabitants of the camp with food. The American Joint Distribution Committee supplemented the inadequate rations allotted by the military government. In contrast to other displaced persons camps, where food was served in communal halls, the Stuttgart residents received food in the form of individual rations for preparation in their own kitchens. In this way, at least, some semblance of home life was preserved.

Preparing for the Future

Most of the center residents strove to attain a normal life and utilized their time to improve their ability of self-support in the future. Everyone had by then criss-crossed Germany in search of members of his family. Some had gone to Radom in the hope of finding some survivors. They encountered open hostility on the part of their Polish neighbors and returned in despair. Not many were fortunate enough to be reunited with their loved ones.

In the Stuttgart center, a Mecca for Radomers,

[Page 86]

the people enjoyed safety in numbers, security offered by a sympathetic UNRRA welfare team, and an illusion of family and community life.

Self-Government

The Radomers in Stuttgart were given free hand in directing the internal affairs of the center. A Center committee was elected with Marek Gutman as president and Henry Berger as vice-president. The committee, considered the official representation of the camp, immediately began to organize some aspects of life in the new surroundings. The major goal of the rehabilitation work was to prepare the people for emigration to Palestine where they might rebuild their broken lives.

Commissions were appointed to take care of the pressing needs.

Public Health

In cooperation with the UNRRA a Health Center was organized, which contained a clinic and a ten-bed hospital. The staff of volunteers, consisting of five doctors and five nurses, did an admirable job of medical care for nearly two thousand people. As a means of preventing diseases, periodic inoculations and check-ups were compulsory. Dr. D. Wainapel headed the Public Health Commission. Chief of the clinic was Dr. W. Boim and, and upon his emigration, Dr. W. Sieradzki.

Education

One of the center buildings on Reinsburg Street was equipped to serve as a school for the growing number of young people and children in the center. Opened as a primary school with 36 students, the “Bialik School” grew in scope with the addition of a high school and its enrollment rose to 125 students with a teaching staff of 18.

The school was accredited by both the U.S. military government and the Jewish Agency. Its graduates were later accepted to many high schools and colleges in their newly-adopted countries.

Among its initiators and teachers were: Moshe Rothenberg, Joshua Rothenberg, Rabbi Henry Griffel, Leib Rychtman, Marek Gutman, Joseph and Carla Gutman, Abram Goldberg, Rachel Landau, Eliezer Gutman, Lea Langsam, Edward Kaltow, Solomon Lederman, Edward Spicer and Igal Weinstein.

The following teachers joined the faculty at later dates: Dr. Joseph Kurtz, Dr. Shalom Levi, Rachel Fishman, Kuba Blatman, Hela Sholowitz, Dr. L. Friedman, Ben-Zion Bergman, Judith Stahl, Esther Frenkel, Mr. Feuereisen, Mr. Weitz, and Mordechai Katz.

Moshe Rothenberg served as principal until his emigration to Israel in 1947. Mordechai Katz then held this post until the school closed in 1949.

Vocational Education

With the assistance of the Jewish Agency for Palestine, the Center Committee organized vocational courses for men and women. At its peak enrollment the school had 300 students with 19 instructors. In 1946 the school was taken over by the ORT organization, which enlarged the courses and supplied the necessary equipment.

The students were trained as electricians, locksmiths, auto repairmen, dental technicians, photographers, cinematographers, bookkeepers. The courses for women included dressmaking and millinery.

The following Radomers worked as instructors: Leon Altman, Yeschaya Eiger, G. Kazdan, Hela Adler, mania Borenstein, Sima Blum, Regina Dresner, Hannah Fruchtman, Marylla Kempner, Nina Migdalek, Rosen Mandelbaum, Frymet Schultz, Jacob Weingart.

Engineer Jacob Babicki was principal of the vocational school.

Concerts and Plays

On The initiative of Cantor M. Rontal and L. Rychtman, a 17 member choir was organized in the center. Arrangements were made with Radio Stuttgart to use their facilities for special holiday programs, featuring the choir and appropriate shows prepared by the “Bialik School” children.

The first Chanukah program was broadcast throughout Germany. It was a source of great satisfaction to the center residents to her Jewish words and music on the Stuttgart radio station. The highlight was a selection of Chanukah songs presented by the accomplished choir, with Paula Frenkel-Shotland as soloist. Among the choir members were: Hela Adler, Dina Birenbaum, D. Eisenberg, Hinda Fishman, Eva Futerman, Paul Gruenwald, Carol Lipson, Jerry Rosenberg, Ada Rosenzweig, Abraham Rosenthal, Leib Rychtman, Streiman, Fela Wercheiser-Peltzman, and others. It was directed by Cantor Rontal and accompanied at the piano by Dr. Cohn.

On Jewish holidays and festivals the school students gave successful dramatic presentations in the Stuttgart Theater on an almost professional level.

First Yom Kippur in Freedom

The first High Holy Day services after years of slavery were held in the Stuttgart Opera House and attended b y all center residents and Jewish members of the United States occupation forces. For those who for years were denied the right to worship, it was an event filled with emotion. Cantor Rontal led the services, assisted by L. Rychtman and a choir.

[Page 87]

First Yiddish Newspaper

The Stuttgart Center had the distinction of having published the first Yiddish magazine in post-war Germany. For lack of Yiddish type, all 23 pages were hand-printed by L. Rychtman and reproduced by an offset press. The second issue, done in the same manner a month later, in January, 1946, contained 60 pages with a wealth of information. Distributed the world over, the magazine, “Ojf Der Frei” (Free Again), was praised as a commendable achievement. The Editorial Committee, consisting of Messrs. Berger, Gutman, Waks and Rychtman, later acquired Yiddish type and continued publication until the Stuttgart Center was dissolved.

Distinguished Visitors

At the end of September, 1945, General Eisenhower made an inspection tour of the Stuttgart Center and voiced his satisfaction with the immense rehabilitation projects undertaken by the liberated Jews.

A month later David Ben-Gurion visited the center. The committee discussed plans for an underground immigration to Palestine with the Zionist leader.

The following year, Mrs. Eleanor Roosevelt was warmly greeted by the center population. She was genuinely impressed with the center school and showed an interest for the people's aspirations.

The center residents also welcomed the visits of Senator Jacob Javits of New York and representatives of Jewish welfare organizations and the Palestinian Brigade, as well as a host of renowned entertainers and writers, primarily from the United States.

The Struggle for Israel

The Jews of Stuttgart considered their stay in the center as a temporary stop-over on the way to the Promised Land. From the very first moment they resisted pressures to become part of the German economy; their only goal was emigration. While Britain kept the gates of Palestine closed to the camp survivors, the Jews held mass demonstrations and stormed the Allied governments with resolutions and petitions demanding the right to go to Palestine and the establishment of a Jewish state.

The United Nations Special Committee on Palestine came to Stuttgart to interrogate the people. It found an intense desire on the part of the Jews to leave for Palestine at once.

Aliyah Beth and “Exodus”

Despite the political barriers, young men and women from Stuttgart braved the uncertainties and dangers and joined the flow of Aliyah Beth, the clandestine emigration movement.

Sarah Neidik-Walach tells in her memoirs of the heroic attempt by a group of Radomer pioneers to reach the shores of Palestine. Within sight of the port of Haifa, they were brutally seized by British soldiers and interned in Cyprus. This group of Radomers, numbering about seventy, finally entered the newly-born State of Israel and was in the forefront of its war for independence.

Several Radomer men and women were also among t he illegal immigrants on the Exodus.

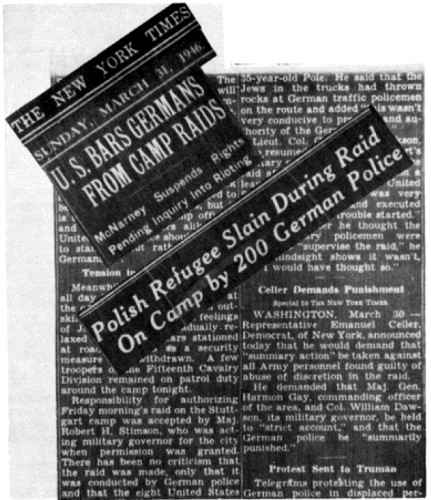

Germans Raid the Stuttgart Center

An Unprovoked Attack

An estimated 250 uniformed German police, armed with United States Army rifles and accompanied by police dogs, encircled the center at 6:15 on the morning of the 29th of March, 1946. Several Germans entered the Jewish militia office in the center and demanded possession of the five weapons stored there for emergency cases. The Jews refused and called the U.S. Military Police; several MP's arrived and ordered the German police to leave.

Meanwhile, the Germans announced through a loudspeaker that they would conduct a search of the buildings, authorized by the American military government, and that everyone, except mothers with their infants, was to leave the rooms and assemble in the courtyards.

The awakened center population looked through the windows and saw the battle-ready lines of Germans in uniform with their guns aimed at the buildings. To them it seemed like a nightmare, reminiscent of events in the concentration camps and ghettos during the heyday of Nazism. This was an unprecedented sight in Stuttgart and the people considered it illegal. The conduct of the Germans was discourteous and rough. When the police entered one of the buildings on Reinsburgstrasse, they encountered a man slowly walking down the stairs. Pointing a gun at him, they shouted: “Get out, you damned Jew!”

The man refused to move, in protest, and after a scuffle he was handcuffed and led to the street by four policemen. His neighbors rushed to his side; a Jewish militiaman attempted to release him. The Germans fired and wounded the militiaman in the leg. Aroused by the sound of shooting and sight of blood, the Jews cried, “Clear out the murderers!” Men and women ran to their houses and grabbed cans, pots, sticks, calling for resistance against the Germans. The police, meanwhile, were plundering some apartments, destroying Jewish property and stuffing cigarettes and candy into their pockets. At the sight of the angry advancing Jews, the Germans retreated with their rifles at the ready.

About two hundred men and women moved toward

[Page 88]

|

|

the police cordon, hurling bottles and pots. The Germans fired another volley and wounded three more men. Samuel Danziger was about to lift an empty gasoline can; a German sergeant walked over to him and fired point blank at his head. Danziger was killed instantly. At that moment a detachment of Military Police arrived with an armored car and ordered the Germans to withdraw. The police cars left behind by the Germans were then demolished by the Jews.

Samuel Danziger

35-year old Samuel Danziger from Radom had survived the Polish-German War in 1939 and four years in the concentration camps of Auschwitz, Mauthausen and Gusen. He had returned the day before the riot from a Paris hospital to join his wife and two young children, also survivors of the Auschwitz camp. He was a confirmed Zionist, reared in Jewish traditions by his father, Noah Danziger, a Hebrew scholar and teacher in Radom.

Funeral services for Danziger were held that same day. As part of the security precautions taken by the military government, the Jews were not permitted to march to the cemetery. Instead, they were driven in a convoy of sixty trucks through the city streets to the ancient Jewish burial grounds. Military honors were given to Danziger during his last rites.

Repercussions

The events in Stuttgart shocked the world and inflamed feelings among the Jews throughout Germany. Protest meetings were held in all displaced persons camps. At a huge rally in Stuttgart, attended by delegations from Jewish centers in Germany, the Jews were urged to remain calm and demonstrate to the world that they were a peace-

[Page 89]

loving people. The situation in Stuttgart and critical conditions in all other camps were cited as additional proof of the need to open the gates of Palestine to Jewish immigration. The American officer, speaking as a representative of the military government, declared that as long as United States troops remained in Germany, a repetition of such provocative acts by the Germans would not be tolerated.

General McNarney, Commander of the United States Forces in Europe, indeed rescinded the authority for German police to enter Jewish displaced persons camps.

The murder of Samuel Danziger had its repercussions in Washington. A memorandum protesting the handling of the Stuttgart raid was given to Secretary of State James F. Byrnes by a delegation of the Jewish World Congress.

Representative Emanuel Celler of New York demanded the punishment of all officials responsible for permitting and conducting the raid.

The developments in Stuttgart were widely reported in the American press and the impact on public opinion resulted in a more liberal policy toward the Jews.

The State of Israel is Born

This joyous occasion was celebrated by the Jews of Stuttgart in an exuberant mood. There was spontaneous singing and hora-dancing in the streets, lasting through the night. May 14, 1948, was a marvelous day to be alive!

Official celebrations with parades and banners, attended by 3000 Jews and government representatives, brought a wave of elation and pride to a people that had awaited this event for centuries.

And when the news came of the invasion of Israel by the Arab armies, hundreds of young men enlisted to defend the infant state.

Aliyah

Heretofore, all immigration to Palestine was routed through underground channels. In charge of these complex operations was the Jewish Agency for Palestine, which had its district office for the Wurttemberg-Baden area in the Stuttgart Center. The activities of the Agency were supervised by emissaries from Palestine, enthusiastic idealists, dedicated to the Jewish cause. The first one in Stuttgart was Naphtali Antman, ably assisted by a young Radomer woman, Sarah Rutman, now Mrs. Leon Mandel of Tel Aviv. They were succeeded by Mr. Ch. Bram, with Alfred Lipson as deputy.

With the birth of Israel and the war of independence, the functions of the Jewish Agency had increased manifold. A stream of immigration had to be guided, which now, in contrast to Aliyah Beth, included women and children. Mounting transportation problems had to be overcome to accommodate all those desiring to leave. This new challenge was met by Mr. Bram with zeal and competence.

Emigration to the USA

Meanwhile, the impatient prodding for a chance to emigrate from Germany began to bear fruit. President Truman's D.P. Bill, permitting thousands of Jews to enter the United States without a quota system, gained momentum.

The intricate facilities for processing applications for entry to the USA and finding sponsors were set up by the American Joint Distribution Committee. The Stuttgart office, which opened in August, 1945, was headed by Mrs. Flora Levine of New York; Mrs. Sonia Zlotnick-Pasternak from Radom was her secretary.

Most of the center residents who registered for emigration to the United States had reached these shores by the end of 1949. The Stuttgart Center was consequently officially closed.

Prosecution of Nazi Criminals

There was a small group of young men in the Stuttgart Center who spared no time or energy in their self-imposed task of finding their former Nazi oppressors.

Tuvia Friedman of Radom, then director of the Documentation Center in Vienna, arrived in Stuttgart in 1946 and, aided by three more Radomer men, Ackerman, Koperwasser and Perl, traveled to the British zone of occupation in pursuit of Radom's top criminals: SS General Boettcher and his right-hand-man, SS Obersturmbannfuhrer Blum. They were identified by the Radomers in a prisoner-of-war camp and consequently handed over to the Polish government by the British authorities. After a lengthy trial in Radom, the Germans were sentenced to death and publicly hanged.

Tuvia Friedman relates in his book, The Hunter, published in New York, the story of his fifteen-year-long pursuit of Adolf Eichmann, the arch-enemy of the Jews. During that time Friedman was instrumental in bringing to trial in Germany and Austria many former SS men and guards who committed crimes against the Jews in Radom and vicinity. Among them were: Janko, Miller, Perkonik and Reich, supervisors of the munitions factory in Radom, and Rottenfuhrer Buchmeyer, chief of the Turk Kommando.

Mr. Rychtman reports that Messrs. Ackerman, Koperwasser, Librach, Perl, Zucker and himself located and brought to trial the former Kommandant of the Vaihingen concentration camp, Obersturm-

[Page 90]

fuhrer Lautenschlager, as well as the brutal SS officer Frick of the Szkolna street camp in Radom.

Residents of the Stuttgart Center testified at the trial in Rastatt against Dr. Dietman, the former Nazi medical officer of the Vaihingen concentration camp, and its notorious SS guards Hecker, Herzog, Piel, Pospischil and others. The French court sentenced five of them to death and the others to long prison terms.

As late as 1947, the International Tribunal in Nuremberg could not find any witnesses against SS General Oswald Pohl, chief administrator of all concentration camps in the Third Reich. Responding to an appeal in the press made by the office of the American prosecutor, Alfred Lipson traveled to Nuremberg and was put on the witness stand. Owing to his testimony, Oswald Pohl was the only one of a group of seven SS generals to be sentenced to death and hanged in the Landsberg prison.

(The facts in the Stuttgart chapter are based on the material compiled by Mr. Leib Rychtman of Tel Aviv.)

by Harry Lerner, former Director of the D.P. Camp in Stuttgart, Germany

The United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration – the UNRRA – gave the people food, clothing and shelter, and it tried to let each person decide for himself his way of life and his future.

Many UNRRA Centers for Displaced Persons were established in West Germany after the Allied victory. The one in Stuttgart West is of particular interest to Radomers and to me. Before the Hitler days, the Jewish community of Stuttgart built a modern old age home there, near the street car line, in a lovely suburb high on a hill. The Nazi government confiscated the home and evicted the people. The U.S. military government turned these buildings over to the concentration camp survivors recuperating at Schloss Langenzelle. Almost all who came from Radom, Poland. They had lost whole families and were unwilling strangers in an unhappy land.

The UNRRA Staff

There was another Jewish D.P. center in Stuttgart, in the suburb of Degerloch. In September 1945, I was sent to take charge of the two Jewish centers, and became Director of a newly organized unit, UNRRA Team 502. I had been in the U.S. Army for four years, two as a GI and two as an officer. I was born in Memphis, Nebraska, and before the war was an attorney in private practice in Omaha, Nebraska. I spoke Yiddish, and wanted to help my people. I was Director till the end of May or first part of June 1946.

The UNRRA staff was sort of United Nations in itself. The members came from many different lands: Czechoslovakia, England, France, Holland, Hungary, Canada, and the United States. Among the DP's were many able people and later some of them became members of the UNRRA staff. They wore uniforms and were paid in military currency.

The Camp Committee

Before my arrival, many UNRRA responsibilities had been turned over to the Camp Committee headed by Mr. Marek Gutman of Radom, a very able man. The camp grew rapidly, and I believed that elections should have been held for a new committee. The old committee agreed. I was shocked to learn that a slate of 9 had been presented to the people on a “yes” or “no” basis, and that the same committee had thus been re-elected. All were Zionists. Mr. Gutman said all political groups in the camp had agreed to the composition of the committee, in which they had representation, and therefore it was a democratic election. A U.S. Army Chaplain had assured them this was a proper procedure. A cold war or war of nerves followed. UNRRA resumed control over the distribution of food, issuance of identity cards, and admissions to the camp. Also, arrangements were made for the DP's to register in the UNRRA office for emigration according to their choice. DP's who worked in the camp were given extra food and cigarettes by UNRRA.

Both UNRRA and the Camp Committee accommodated themselves to the situation, and there followed an era of close cooperation. Specific problems and projects, as they arose, were referred by one body to the other for suggestions, help or execution. The camp became known as the “muster larger” or best camp in Germany.

Camp Institutions

The first institutions in the camp concerned food, clothing, health and social activity. In the mess hall at the corner of Reinsburg and Birmarckstrassen, meals were served by the UNRRA three times a day. In the evenings, the hall was used for meetings, plays or dances. The Camp Committee usually handled these arrangements. Some people in the camp desired a “kosher kitchen”. This was set up in another building where social activities also took place, including oneg Shabbats. As the number of family associations grew and the apartments became better equipped for cooking, more and more of the food was distributed dry or in bulk by UNRRA direct to the DP for preparation in the home. The source of the basic food supply was the U.S. Army. Supplemental food came from the

[Page 91]

American Red Cross and the Joint Distribution Committee. The American Red Cross also provided cigarettes.

Clothing came from the United States via UNRRA, American Joint and Red Cross, and from Germany via the U.S. Army. Food was distributed regularly, but clothing only occasionally.

Disease was a constant threat. The people would not come voluntarily for inoculations, such as for typhoid. To meet the situation, UNRRA would not honor its food ration cards or identity cards unless they were stamped to show that the DP had checked with the Dispensary each month. This may have seemed dictatorial, but we had no deaths due to disease. Our Dispensary on Reinsburgstrasse was available 24 hours a day. It gave general care and treatment, and our doctor referred special cases to physicians or hospitals in Stuttgart for treatment at military government expense. Later, as the population of the camp increased, maternal and child care were provided.

Growth of the Camp

As people in the DP camps throughout Germany regained their strength, they set out to find relatives, friends, or just anyone from the old home town. In Stuttgart, there were more Jewish Radomers than anywhere else, including Radom, and Radomers in other camps were drawn to Stuttgart. Living conditions in Stuttgart were better than in most other camps, and people who were not from Radom also came. By the time the liberated had made their choice of a camp, a new wave of human refugees was on the way: people who had not been in concentration camps, described by the military government as “infiltrees”. Most of them had been Partisans during the war, or in the Soviet Union, and only a few were from Radom. All were Jews from Poland, except that a few had Russian spouses. The camp also acquired 12 Hungarians from a prisoner of war camp, who somehow had been in the Hungarian military, although Jewish. The liberated from Schloss Langenzelle who began the camp in August 1945 numbered less than 200, but a year later the camp housed about 2,000. In view of this, the UNRRA requested the military government to requisition additional apartment buildings.

Uplift

As the camp matured and stabilized, and food, clothing, shelter and medical care became a sort of routine for the people about which they had no worry and no ultimate responsibility, they were able to concentrate their thoughts and energies more and more on their own uplift: educational, cultural and economic. By now also there were many family groups in the camp, and there were enough children to set up a school. The UNRRA Team had been living in the camp on Reinsburgstrasse, and we arranged to move out so this building could be turned into a cultural center. It was a great day for the camp when it was opened, officially known as Beth Bialik. Officials of military government, UNRRA, and the Camp Committee participated, and life in the camp became more meaningful. Classes for young and old were set up in English and Hebrew; courses in various crafts were started with the aid of ORT tools and equipment. Our object was to help our people learn a language and some useful trade or occupation which would help them be readily assimilated in any land to which they might emigrate. A library was also opened, with some books coming from the United States via the Jewish Day and the Workmen's' Circle. Art classes were organized. The sadness or grimness that had hovered over the camp was broken by the singing of merry songs at school, and by the pursuit of knowledge.

We Want Out

Each person was free to use his day as he saw fit, and each went his own way if he chose. But above all else there was one thing in common as their goal: to get out of Germany. It was a hated land, and perhaps a hated people. There were two great hopes for emigration: Palestine and the United States. There was much bitterness before emigration anywhere was substantial.

In December 1945, President Truman directed the U.S. authorities in the U.S. Zone of Germany to facilitate the emigration of the DP's to the United States. It was several months before the first ship left. On that ship there were more from Stuttgart than from anywhere else. We were very proud of this. It was due to the foresight and ability of our UNRRA staff and the availability of corporate affidavits from the Joint. The authorities considered Mr. Truman's directive applicable to persons in the U.S. Zone on the day it was given, and for many months, people who could not show that they were in the Zone then, and people who came later, felt they were suffering discrimination.

High hopes for immediate mass emigration from the camps to Palestine were dashed by British policy. Aliya B was developed as the answer. Stuttgart was en route, and as people from the camp went on Aliya B, they left behind with comrades their UNRRA identity and ration cards for the use of other Aliya B-niks, who took their place in the camp until the time came for them to do likewise. UNRRA counted the number of people in the camp, which remained relatively stable. In time, people

[Page 92]

in the camp told of letters received, more from Cyprus than from Palestine.

Events of Note

Events of interest to the camp as a whole included the accidental death of two of our younger people on a motorcycle only a block from the camp. Another was killed on a motorcycle several months later. Speed apparently was an unfamiliar phenomenon. On February 22, 1946, our people had trouble on the street cars. Before investigation reported any results, there took place the most shocking event of all: The “invasion” of the camp by the German police on March 29, 1946. The military government until then had used U.S. Military Police, or our camp police, to maintain order in the Center. The UNRRA Team learned via a telephone call from the camp that the German police were there with carbines and dogs. By the time I arrived, one DP was dead and three injured one perhaps permanently.

|

|

| Mr. & Mrs. Harry Lerner Stuttgart, 1946 |

Other events were more pleasant, such as the opening of Beth Bialik, already mentioned. There was also the visit of General Eisenhower in the spring of 1946. The march (without a permit, but in a friendly atmosphere) to the U.S. Embassy in Stuttgart in October or November 1945 to seek U.S. assistance in emigration to Palestine. The visit to the camp of members of the Anglo-American commission on Palestine, when Mr. Bartley Crum heard testimony. And the visit of Mr. Ben Gurion about March 1946.

We had births and weddings in the camp, and an outstanding event for the camp and for me was my own wedding, to Clare Smocleare of London, England, who had come to the Team from the Jewish Relief Unit, a British organization, to do welfare work as a volunteer. Our civil marriage was at the Standesamt in Stuttgart May 28, 1946. We arrived as scheduled, and the clerk asked us to wait. After a while, I told him we were still waiting and his reply had been a source of amusement to us ever since. He said we had to wait till the bride and groom came. Our whole group, including witnesses, was in uniform, and he had expected more festive attire for the bridal couple. After the civil ceremony, we returned to work, and two days later, we were married by Rabbi Eugene Cohen, an Army chaplain, at the Jewish Welfare Board in Heidelberg. Mr. Marek Gutman, chairman of the Camp Committee, gave the bride away. We have three children, and our home is at 5020 Park Place, Washington 16, D.C.

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Radom, Poland

Radom, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2024 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 20 Feb 2014 by MGH