|

52°14' / 19°22'

Translation of “Kutno” chapter

from Pinkas Hakehillot Polin

Published by Yad Vashem

Published in Jerusalem

Project Coordinator

Our sincere appreciation to Yad Vashem for permission

This is a translation from: Pinkas Hakehillot: Encyclopedia of Jewish Communities, Poland,

Volume I, pages 223-229, published by Yad Vashem, Jerusalem

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

(Page 223)

(district of Kutno)

pp. 223, 224 and 229 translated from Hebrew by Carole Borowitz

pp. 225 to 228 translated from Hebrew by Thia Persoff

Population in figures

| Year | General Population |

Jews |

| 1764/1765 | (?) | 928* |

| 1800 | 2278 | 1401 |

| 1808 | 2105 | 1357 |

| 1827 | 4620 | 2859 |

| 1857 | 5868 | 3859 |

| 1897 | 10356 | 5169 |

| 1921 | 15976 | 6784 |

| 1931 | 23368 | 6440 |

| 1/9/1939 | (?) | ca 6700 |

From Jewish settlement to 1918

Kutno is known to be settled in the 11th and 12th century, achieving city status in the mid-15th century. During the 16th century, Kutno was a private estate belonging to aristocrats and became a trading centre for handicrafts in the rich agricultural surroundings. In 1753 the city was nearly totally destroyed by a fire and did not recover until almost the 1880's. In the first half of the 19th century, the textile industry began to develop in Kutno, but it did not result in a clear revival of the economy of the town. Apart from that, the laying of a railway line through Kutno, about in the middle of that century, influenced the rapid development of the town, which from then on became a centre for the food industry and commerce in grain produce. From about 1867, Kutno became the seat of the district authorities. It can be assumed that the Jewish community in Kutno had already been established in the middle of the 15th century, the most ancient document concerning Jews in Kutno being from 1513. This is an authorization given by the king to three Kutno Jews named Moshe, Salomon and Leibke, limiting the cancelling of the debts owed to them by their non-Jewish debtors to one year only.

Owing to the economic activities and cultural achievements of the Kutno Jews, one can note traces of the existence of Jews known as “Kutner” in Germany and Holland, in the 17th and 18th centuries (for example, in 1685 in Amsterdam lived the printer Asher ben Anshel Kutner). The Rabbi of Wielkutz (Wielkie Oczy), Rabbi Mordechai ben Shmuel, who was from Kutno, relates in his essay “The King's Gate” (Zolkiw 1763), about an interesting custom that originated in Kutno: the local rabbi declared that three Jewish elders of the city should confirm the time of sunrise each morning, for the morning prayers, a perpetual reminder of the destruction of the Temple (in Jerusalem). In 1775, there was a Jewish doctor in Kutno, Marek, who gave his name a Polish sound. In 1784, Moshe ben Shlomo served in Kutno as the commercial attaché of the Austrian ambassador in Poland. Moshe Ben Shmuel from Kutno was an arms supplier to the Warsaw rebels in 1794, and in 1807, during the period of the Duchy of Warsaw, he was appointed as an intermediary for the Warsaw community.

In the second half of the 18th century the Jewish community of Kutno totalled about 200 families, and in the 71 surrounding villages and two small minor towns of the Kutno community (Żychlin and Gostynin), there were altogether 190 Jewish families. By the end of the 18th century, during the Prussian rule in Kutno, the Jewish population in the town increased. According to the census drawn up by the Prussian authorities in 1796, the following were the occupations among the Jews of Kutno:

| Occupation | # of Jews employed |

% of total employed |

| Handicraft | 158 | 41.3 |

| Commerce | 95 | 25.0 |

| Transport | 6 | 1.6 |

| Servants and day workers | 56 | 14.7 |

| Community clerks and independent professions | 47 | 12.4 |

| Unemployed | 19 | 5.0 |

| Total | 381 | 100.0 |

The craftsmen were mostly 74 tailors, 26 furriers, 26 saddlers, 11 butchers. Most of the salaried workers worked for the craftsmen. At the head of the branches of commerce – merchants and shopkeepers – there were: 18 wool merchants, 10 leather merchants, 27 innkeepers and tobacco dealers, 21 stall owners. The significant number of community workers is explained by the fact that the community of Kutno served not only its own people, but also the Jewish inhabitants of the surrounding villages and two additional smaller towns. It is also possible that some of the community workers held these posts as extra jobs or were registered fictitiously as community workers in order to claim tax relief. The category “unemployed” included 8 young families supported by their parents, 6 elderly and 5 handicapped.

The occupational structure of the Jews living in the surrounding villages was different from that of Kutno. There the most frequent trades were: barkeepers 32.5%, innkeepers 17.9%, brewers 11.4%, servants and hired workers 20.3%, craftsmen 13.9%.

The material situation of the Kutno Jews was defined by the meticulous Prussian tax authorities, who were far from liberal, as follows: poor, exempt from tax – 9.2% of the entire Jewish population; not wealthy, paying a small amount of tax – 42.1%; moderately wealthy – 44.1%; wealthy – 4.6%. The material situation of the Jews in the surrounding villages was better. There, the poor numbered only 2.6%, the not wealthy 36.9% and the wealthy group – 52.6%. The taxes and levies imposed on the town and the community by the state treasury weighed heavily on the material situation of the Jews. In 1796 the taxes due from the Jews of Kutno amounted to 20,000 florins and 15,000 florins from the Jews in the surrounding villages and smaller communities. The community in Kutno was deep in debt and could not even meet the interest payment, which amounted to 3,500 florins in 1791.

As mentioned, the attempts in the first part of the 19th century to revive the textile industry in the town did not succeed. The fate of the unsuccessful factories also struck those in Kutno, which had previously won a medal at the Warsaw industrial fair (1826). However, the food industry started up in Kutno. In the 1850's, two water mills were working in Kutno, 9 windmills, a distillery and a brewery, whose owners were mostly Jewish. The Warsaw banker Herman Epstein built a sugar factory “Konstancja” in Kutno in 1852, which, then, was one of the largest in the world. Later, Mieczyslaw Epstein, another family member, managed it.

By the end of the 19th century, a significant change in the occupational structure of the Jews of Kutno could already be seen, compared to that at the end of the 18th century. According to the numbers in 1897, commerce went up to the top of the list: among the 1,496 family heads, 38.3% now supported themselves in business, and 30.9% were craftsmen. Among the craftsmen, 64.3% were occupied in the clothing branch. The numbers of those in transport (carters, messengers) also rose to 5.4% of all the Jews occupied. A characteristic impetus accompanying these changes was the decrease in self-employed workers and an increase in salaried workers (salesmen, assistants, etc.), who were not themselves owners of businesses or workshops. This trend continued until the 1920's, and is witness to the proletarisation and impoverishment of the Jews. The trend grew in the period of the First World War, when a significant portion of the Jewish population existed solely thanks to the communal kitchens set up by the Jewish community and other social institutions. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the Kutno community was included among the important influential communities in that part of the country. This is confirmed, among other things, by the fact that, in the various delegations of local and national communities, set up for ad hoc purposes, representatives from Kutno participated in many instances. One of these representatives, Moshe ben Jeremyahu Maizel, a Kutno community leader, was among the Jewish delegates attempting to cancel various limitations imposed on Jews planned by the government of the Warsaw principality. Already by the end of the 18th century, the institutions and administration of the Kutno community were quite split into sections. Then, the community supported, apart from the rabbi, two religious judges, four ritual slaughterers, four cantors, 11 teachers, 6 synagogue attendants, 5 grave diggers, a religious scribe and a prayer caller. The Kutno community then had a cemetery (which was enlarged in 1766), a synagogue, a bathhouse and a school house, all constructed of wood. In 1766, the building of a new synagogue was started, a grand edifice, which was completed in 1799. This temple stood as an historic site until 1939. The Chevra Kadisha (burial society) was founded in the 18th century (the oldest preserved entry in the register dates from 1755). The average annual income was up to 900 florins, and the society also inspected the bathhouse and the society for visiting the sick. The congregation performed funeral rites for the sick and homeless beggars and vagrants. In 1796, the community leaders were a faithful reflection of the social groups in the community: Szalom ben Majer – cloth wholesaler, Hirsz ben Lajbel – hired ritual slaughterer, Wolf ben Chaim – bartender, Szlomo ben Abraham – tailor.

At the end of the 19th century, new institutions were set up in Kutno, mostly traditional although, apart from the synagogue and the religious school, six Hassidic prayer groups were established. Apart from the small one-room schools (cheder) privately and community-run, where 24 teachers taught, a Talmud Torah was founded, where 150 pupils aged 5 to 13 from low income families studied. In the 1880s the Gur Hassidic group set up a charitable fund, which distributed to the needy loans up to 50 roubles at a low interest and small repayments (1 rouble per week).

From its very beginning, Kutno was famous as a centre for Torah study, mainly because of its rabbis. The rabbinical appointment in Kutno was among the most respected in the country. The first rabbi of Kutno to be mentioned was Rabbi Moshe Yekutiel Hacohen Kaufman, the author of “Lechem HaPanim” (“Shrewbread”). Following a controversy in the community, he returned to his original city Krotoszyn about 1710. History records two more rabbis in the 18th century – Rabbi Issachar Brisz, son of Rabbi Benjamin, ascetic and skilled in mysticism, known by the name “Rabbi Brisz Hassid” (his grandson Rabbi Abraham is famous as the Admor (religious scholar) of Ciechanów, and Rabbi Israel Hacohen who was born in Kutno but no details of his life or activities have survived. At the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th, Rabbi Tuwya Bryn (died in 1819) presided in the priesthood in Kutno. Starting from 1820, the appointment of rabbi in Kutno went to Rabbi Eliezer Brisz, who was formerly rabbi of Leszno, well-known for his scholarship. He died in 1831. In the 1840s, Rabbi Moshe Aharon Kutner served as rabbi (died in 1853); he was renowned for his Torah scholarship and for his Talmud teaching and interpretation skills. He was also a rabbi with Shlomo the Admor from Radomsk. For a short period (1848-1852) Rabbi Fliegeltaub served as rabbi in Kutno, and was also the rabbi in Koło. Rabbi Moshe Yehuda Leib Zilberberg honoured Kutno; he was the author of “Zayit Raanan” (“Fresh Olive”) and “Tiferet Yerushalayim” (“Glory of Jerusalem”).and grandson of the rabbi from Łęczyca. He served on the rabbinical council in Koło, Sierpc, Dobra, Lask and Kutno. In 1857, he emigrated to Jerusalem and died there in 1865. Rabbi Jehoszua Ajzyk, known as “Harif” (“sharp”), brought to the priesthood in Kutno from Slonim, but served for only a few years since, according to the “Litvak” (Lithuanian) and “Mitnagdim” (opponents to Lithuanian Hassidim) practice, a peaceful compromise could not be found with the local Hassidic practitioners. He returned to Slonim in 1861. He left behind him many books, among them “Emek Yehoshua” (“Valley of Joshua”), “Nachlat Yehoshua” (“Joshua's Inheritance”), “Ibbei Hanachal” (“Blossoms of the Valley”), and “Sfat Hanachal” (“Shore of the Valley”). From 1861 until 1892, one of the greatest Torah scholars of his generation served as rabbi in Kutno – known in his lifetime as “the Rabbi of the Diaspora” – Rabbi Israel Jehoszua Trunk, also called Rav Joszele (he was born in 1821 and died in 1892). At the age of 20, he was appointed rabbi of Szrensk. Later, he was rabbi in several congregations and finally rabbi of Kutno, where he also was head of a large Yeshiva (Jewish study centre). His rabbinical interpretations, published in the form of questions and answers, or heard at religious courts, were accepted by rabbis in Poland and outside. His whole life, he was faithful to the idea of settlement in the Land of Israel and emigrated in 1885 with his son-in-law, the rabbi of Kalisz, Rabbi Chaim Eliezer Waks. With money from donations they bought houses in Jerusalem and turned them into residential religious colleges (“Kollel”). They also promoted the planting of an orchard for etrog fruit (note: ritual fruit for Shavuot) near Tiberias and proclaimed their preference for the etrog grown in the Land of Israel over the etrog grown in Corfu. In the “shmita” (fallow) year 1889, Rabbi Jehoszua Trunk was allowed to cultivate the fields on condition that he participated in the permission granted to another great religious scholar of that time, Rabbi Ytzhak Elchanan Spector from Kowno. In 1873, he published his works “Chossen Mishpat” and “Yeshuot Yisrael”. His other books, for example “Yeshuot Malcho”, and “Yevin Daat”, were published after his death, in 1921-1922, by his grandson Rabbi Icchak Jehuda Trunk. Many years after his death, stories circulated about the quick wit and sharpness in arguments of Rabbi Jehoszua. After the death of Rabbi Jehoszua, his son, Rabbi Moshe Pinchas Trunk, became rabbi of Kutno (died in 1912), previously rabbi of Wiskitki. After him, the last in the line of Trunk to serve in Kutno was Rabbi Yitshak Yehuda (died in 1939), author and teacher who added to his grandfather's book “Yevin Daat” which he published, his own writing “Hasidei Avot”. Judges also participated on the rabbinical council, the greatest among them being Rabbi Jehiel Michal Elberg (died in 1857), Rabbi Jehiel Brisz Sztruk (died 1875) and Rabbi Lajb, who served during the first years of the 20th century.

Kutno also served as a scholastic centre. Already in the 1920s, a non-religious elementary school for Jews was founded here. In the years 1830-1831 among the pupils at the rabbinical school in Warsaw were two from Kutno: Yitzhak and Naphtali Nelkin (this school was well-known primarily as an educational centre for gifted pupils, not only for rabbinical education, but even for supporters of cultural assimilation with the Polish people). Two doctors from Kutno were also representative of this education: Doctor Josef Handelsman, who was head of the rebels of the Gostynin area during the revolution of 1863 and was exiled to Siberia in 1865, and Doctor Felix Orenstein, physician and public worker well-liked in the area. Nahum Sokolov studied at the Kutno Yeshiva and also Sholem Asch (born in 1880 in Kutno), who immortalized his hometown in his books “The Shtetl” (The Village) and “Motke the Thief” (Motka Ganav), and especially its ordinary people.

|

|

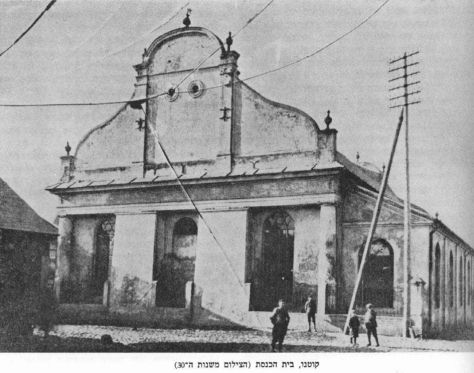

| Kutno, synagogue (photograph of the 1930s) |

Modern political life had developed early in Kutno. In 1898, an organized political group of “Hovevei Zion” (“Lovers of Zion”), by the name of “Bnei Zion” (“Sons of Zion”) was already active there, with over a hundred members. In 1906, “Poalei-Zion” (“Workers of Zion”) was already active in Kutno; its members were very active in the 1907 election for the second Duma (the Russian parliament). Before the First World War the “Mizrakhi” (“East”) and the “Bund” organizations were established. In 1912 the youth groups “Tsehirei-Zion” (“Youth of Zion”) and “Pirkhei-Zion” were established, and in 1916 the “Tsehirei Ha'Mizrakhi”, “Ha'Khaluts” and “Bnot-Zion”. At the same time “Jugend”, the youth organization of “Poalei-Zion” was founded.

Inspired by the political parties, various cultural institutes were founded in Kutno during the first two decades of the 20th century. The society for literature and music The “Zamir”, which had its own library, and later out of it started the “Culture for the Weary” and a Drama Club. The latter became the “Jewish-Labour-Stage” after some years (“Yiddishe Arbeter Bine”). At that time, the Zionists established a library, named after Ekhad-Ha'Am, with most of its books in Hebrew. In 1908, the society for literature, “Literarishe Gezelshaft”, was founded. The best of the Jewish writers and political activists of the time, in this and other countries, had lectured in that society and in the “Kultur Lige” society.

In the area of modern education, a “Cheder Metukan” was established (even before 1915), a kindergarten (1917) and, in 1918, A. Sh. Alberg, one of the original members of “Ha'Mizrakhi” and the kehila's long standing leader, had established a dual-language High School named “Am Ha'Sefer” (People of the Book). In 1916, Noach Prilucki came to Kutno and founded the first elementary school named after the author Perec, in which the teaching language was Yiddish. This school continued to function until 1935.

Between the two World Wars

In the two decades between the two wars; the numbers of the Jewish population in Kutno had declined, and their proportion in the general population went down even more. The reduction in their number was due to some of them migrating to larger towns in search of a better livelihood, and in addition to that the decline in the percentage rate was a result of annexing a few villages to the town for the purpose of strengthening its “Polandish” character, particularly in connection to the town government's elections.

The change seen in the professional structure of Kutno Jews during the 19th century, increased in the 20th . The impoverishment and the politicization, specifically to Jews (not only to the Kutno Jews) was most considerable; in 1921 the hired labourers were already 55.8% of the Jews active in the field, but only 44.2% among the independent ones (those that had their own workshops, stores, or stalls). In the garment section (in production, services and marketing) 57.5% of all those active in the field were employed. 23.8% were those employed in the food section. In the rest of the fields the Jews were represented in minute percentages. In the 30s, the Jews held a few factories – few windmills, 2 factories for chicory, a beer brewery, and one of the country's largest plants for alcohol distillation – but all those did not employ Jewish labour. The well-developed railroad junction in Kutno, which was a good livelihood source for the locals, was a closed shop with absolutely no entry for Jews. One of the specific jobs for Jews in Kutno was gardening, which provided livelihood to 20 families; a rose plantation owned by a Jew was very famous.

The main occupation of Kutno Jews was, therefore, the small stores and at-home workshops. This kind of occupation did not afford them a basic livelihood. Especially bad was the situation of those Jews that worked at home (tailors, shoemakers, hatters) who got orders only during certain seasons of the year. More severe was the situation of the hired labourers, who were seldom paid on time, or long delayed. Their day work was not kept to an 8-hour schedule, and they were not insured in case of sickness or unemployment, seasonal or continuous.

The Endek's [National Democratic Party] ban on the commerce and services held by the Jews had worsened their economic condition. In June 1936 there was an attempt to instigate a pogrom. Incited by local anti-Semites, a 12-year-old boy had thrown a stone at a “Holy Bread” holiday parade, and injured one of the participants. The Jews were accused of desecrating the parade. A joint action by the labourers organized in the “Bund” and in the Polish Socialist PPS had prevented the riot.

Economic-social institutions tried to ease the severity of the financial condition of the Jews by organizing mutual aid. The Jewish merchants association, which was formed in 1927, had their bank extend low rate credit. In 1928, the bank had 270 members. In 1932 the small business merchants had founded their organization, and had 94 members in the first year. Its main purpose was to provide business permits for its members, giving credit and organizing cooperation in small commerce. The organization of Jewish craftsmen was established during the first years between the wars. During those years were also founded (mainly under the auspices of the “Bund”) the first professional organizations of the Jews, among them that of the transportation workers and the needle workers (tailoring/sewing). In 1935, after years of struggle, the needle workers had achieved their demand for an 8-hour work day for its members.

During the time between the wars, all the political parties and their youth organizations that functioned in Poland had branches in Kutno. In the 30s, the Zionists almost doubled their ranks (this was in almost all of the parties). In the elections for the Zionist congress of 1931 were 373 participants, but in the 1935 elections the number of voters increased to 626, and in 1939 it increased to 641. Among the Zionist parties, the “league for the working Israel” stood ahead (in 1935 with 153 votes, in 1939 with 282 votes). In the second place was the “Zionim Klaliyim” party's “Al Ha'Mishmar” group (in 1935 with 153 votes, in 1939 with 219). After them came “Ha'Mizrakhi”, the Grossman group and others that received a few votes, and some tens more. Among the youth groups in Kutno the first was “Ha'Shomer Ha'Tsair”(in 1936 they had about 200 members). They organized a pioneering training group of their own in the Kutno area. The “Zionist youth” was established in 1930 and was very popular. It was clear to see that, in Kutno, the influence of the Revisionists was very strong. In the election to the Zionist congress of 1931 they got 122 votes out of some 373 votes. In the following years, “Beitar” – a party founded in 1930 out of the “Ha'Shakhar” (founded in 1923) – received quite a few more votes. And in 1934 it had 200 members. In the “Brit-Ha'Khayal” that was founded in 1930, there were about 50 members. “Agudat-Israel” in Kutno and organizations annexed to it were active mainly during the election to the Jewish community and the town council. They were also very active in the education field. The “Bund” was strengthened by the professional organizations which it formed. In the 20s, the “Volkist” groups developed vigilant activities, mainly in the craftsmen and the small merchants associations. The influence of the Volkists declined with the passing years. The Jewish political arc was completed by very active communist groups, who often were heading the local strikes and demonstrations. The funeral of the communist Gucia Zelkowicz from Kutno (1936), who was tortured to death in Łęczyca's prison, turned into a mass demonstration, with the participation of local Jewish and Polish labourers.

The Zionists had a decisive influence in Kutno: in the 1924 election to the administration of the community. They, in coalition with the craftsmen who were under their influence, received 6 mandates while the Alexander's devotees received 2, the “Bund” received 2, and the “Aguda” and “Volkists” – all in one list in 1 mandate. In the next election, in spite of losing a bit, the Zionists still kept their upper hand. In 1931 they, with the craftsmen, won 5 mandates, the Volkists with the small merchants won 2, and the rest of the parties and groups (“Agudat Israel”, the butchers, “Alexander's devotees”, “Agudat-Israel Labourers”, and the socialist craftsmen who were influenced by the “Bund” – all in one list) won 1 mandate. In the 1936 electing the Zionists won 4 mandates, “Agudat Israel” and “Agudat-Yisrael Labourers” won 3 and the “Bund” won 3.

The number of the mandates in the town council that the Jews won does not reflect the estimate number of the Jewish community in the general population, nor does it reflect their economic importance and political activities. When in 1919 the Jews received 13 mandates out of the 24 available, the regional authorities nullified the election and ordered to have a new election. But the Jews won those, too, with 11 mandates: the Zionists – 6, the Volkists – 2, the “Bund” – 3. Therefore, in the next elections the authorities had taken administrative measures (among them, as mentioned, the annexing of the villages) so as to prevent the correct representation of the Jews in the town's council. And indeed, in 1939 all the Jewish parties together won only 5 mandates (the Zionists – 4, the “Bund” – 1) out of the total 24 mandates. As a result of this situation, part of the town's responsibility toward its Jewish constituents (like education and welfare, grants for cultural organizations, sports, and such) fell on the shoulders of the Jews themselves, on their political organizations and social institutions, and foremost on the shoulders of the entire community. The community allocated the means for “Cheders” and Jewish schools, for cultural institutes and welfare like “Linat Ha'Tsedek” (providing free sleeping places for the needy) and visiting the sick. Starting in 1937 it supported the TOZ (Jewish Healthcare Association) which provided medical aid to hundreds of poor Jews, and administered in Kutno a daily dormitory for poor children. In addition to acts of one-time help with food (mainly in Passover), firewood for heating, and warm clothing in winter, the community had steadily added towards the food for the “Yeshiva” students and poor pupils. In the benevolence society of the community were 581 members in 1938 (184 craftsmen, 318 merchants and peddlers, 79 farmers-gardeners), and the average amount of loans was 20-300 zlotys.

In Kutno, as in the other Polish towns during the time between the wars, there was an awakening in the cultural life. In the dual-language high school “Am Ha'Sefer”, Jewish pupils from the surrounding area studied too. Soon after the war ended, a public elementary school was established for the Jews (“Szabasówka”) and, in 1926, a new building was built for it (part of the building expenses came out of donations by the Jewish population). In 1928 a second elementary school named after Medem (Vladimir Medem, Bund politician) was built – with Yiddish as the teaching language. It was cared for by the local branch (140 members) of the CISZO (Yiddish Schools Headquarters) and the local “Bund”. The pupils, mainly children of day workers, received food and winter clothes. Under the auspices of “Agudat-Israel” were “Talmud Torah”, elementary “Ha'Torah school” and a school for girls “Beit-Yaakov”.

Institutes that were established before the First World War or during it had continued to function. Between the two World Wars, a public university was founded in Kutno and a branch of YIVO (Institute for Jewish Research). Unrelated to them, all the political parties and their youth groups were highly active in cultural ventures: they activated amateur clubs, evening classes in Hebrew and Hebrew literature and Yiddish, had arranged lectures and parties. The group for exercise and sport that started in 1915 had become the “Maccabi” organization, and new sports organizations were formed: “Stern” (under the auspices of “Poalei Zion”), “MorgenStern” (under the auspices of the “Bund”), “Khashmonai”, “Yardenya”, “Bar-Kochba”, “Ha'Gvura”, “Beitar” (under the auspices of the Zionist organizations). Those organizations' goals were not only for high achievement, but also sports education for all. Some of those had music bands attached.

The Shoah

At the start of the World War II, there were heavy battles for the town: Kutno was under a heavy shelling because of the military installations there. The town's people, Jews included, left in droves, though most of them returned soon because the roads in the area were blocked and because of the encirclement by the German armies. On Sept. 9th there was a particularly strong bombardment, in which 18 Jews were among the casualties. The town was full of injured people (temporary hospitals were arranged even in the synagogues and the “Beit-Ha'Midrash”) and Jewish refugees. The Germans entered Kutno on September 15th and on the evening of September 19th they carried out an extensive search and concentrated hundreds of men (Jews and Poles) in one of the churches and in the movie house “Modern”. They were incarcerated there for about 2 days and then one group of Jews was sent to Piątek for hard labour. Another group of 70 Jews was sent to the civilian prisoners of war camp in Leczyca.

Abusing religious Jews was a daily occurrence. The Germans would abuse bearded Jews and kapota-wearing Jews (they pulled the hair with the skin). Because of that, many had cut their beards as short as they could, and gave up wearing the kapota. One day the Germans took out the people praying in the Beit-Ha'Midrash and ordered them to pick up the horse manure with their bare hands. The testimonies about the fire in the great synagogue are unclear and contradictory. What is known is that it was doused with gasoline and set on fire, but some say that the fire died down in spite of being restarted a number of times. Another version is that the commander of the German police ordered putting out the fire, concerned that it may spread.

One way or the other, the fact is that the interior of the synagogue did not burned. Later the Poles and the Germans had destroyed it: they tore out the floor, the doors, windows and the benches. All that was left was the burned out shell. In spite of being prohibited to lead a religious life (particularly communal praying, and the ritual slaughtering), they did not stop in the period before the ghetto was established. Minyans (groups of ten men) got together for prayers in private homes, the devout continued to study the Torah and the Chassidim arranged feasts.

The constant enlistment of Jews to various work started in December 1939. The authorities had determined then that all males of 14 to 60 were to work a full day twice a week at work places for the Germans. In January 1940, also women 18 25 had to work for them.

In Kutno, as in the other conquered town, the forceful pillage of Jewish belongings continued. The Germans robbed the merchandise from Jewish stores, so the Jews made efforts to sell what they could, closed the stores and turned towards illegal business. The Germans had confiscated possessions in Jewish homes mainly, thanks to reporting informers. Factories and flour mills belonging to Jews were confiscated in the whole area and a few times, penal taxes were levied on them.

The Judenrat (it had 6 members, as ordered by the authorities) was established in 1939 according to one version, but according to a different version it was after the establishment of the ghetto in June 1940. The chairman of the Judenrat (or of the administration of the Jewish community at the beginning of the occupation) was Alexander Falc. Some members of the Judenrat were: M. Zandel, attorney P. Goldszirer, L. Praszker, Y. Kovic, Sz. Opoczinsky. The first assignments the Germans had charged them with were the collection of moneys for the payment of the penal taxes, and the conscription of work-teams. The local Gestapo-head gave the Judenrat many difficulties; he ordered them to renovate a house for him and to furnish it well. For this, the Judenrat had to collect about 15.000 marks. When the house was ready, he locked up some of the Judenrat's members for few hours. He also ordered them to dress up beautifully a nice-looking young Polish girl, send her to the barber and fulfil all her wishes. This sadist had personally abused the Jews: he walked in the streets and using a rubber bat would hit any Jew he happened to see, even women, which he undressed until naked.

Concerning the Jewish community, the Judenrat's urgent task was the organizing of aid to the refugees, whose number in Kutno on Jan. 1st, 1940 was 1,315. By June 1940 it increased to 1,700-1,800. They came mainly from the northern areas and Pomerania, Danzig, Inowroc.aw, Wrocław, Bydgoszcz, Ciechanów, and even from distant towns as Grodno, Szweciany, and Lwów. Close to the establishment of the ghetto, in June 1940, the Germans brought to Kutno 150 Jews from nearby Dąbrowice. The Judenrat had appointed a special board for taking care of the refugees: Y. Borowski – a past secretary of the community administration, A. Ika – a past accountant of the community and L. Nayman. The fund that was given to them came from donations and a grant from the “Joint” (Joint Distribution Committee).

On February 1st, 1940, the refugees in Kutno were in danger of expulsion. According to one version, on first of February the German authorities had ordered all the Jewish refugees to leave the town, and all those that will stay, would be put in jail. But as it happened, some of them left after being supplied goods by the Judenrat, most stayed but were not punished. This planed expulsion – as it was in other places – was certainly part of an action that was continued in those days: The settling of many Germans in the town. In February, a group of local Volksdeutsches had done an intensive plunder of Jewish properties for the new settlers: From most of the Kutno Jews they took furniture, bed linens, and all sorts of household items. Furniture not in good shape was chopped up to use for heating. In this robbery the Germans were helped by Polish informers and extortionists, and even Jewish informers. At the same time the German authorities had taken apart many wooden houses in bad shape, in the quarter containing a large Jewish population. As a result, about 500 families were left homeless.

In spite of all the tribulations, witnesses describe Kutno of up to June 1940, as a relative haven for the Jews. The town is situated close to the border between the Wartegau and the General government, at the crossroad of important railroads. That gave the Jews comfortable opportunities for smuggling. They travelled with their merchandise to faraway places (among them, Lodz and W.oc.awek). They earned good money, and some had prosperous business. Even among the refugees poverty was less than in other towns, because they earned by smuggling. There was abundance of merchandise variety, and the Germans (civilians and wearers of uniforms) bought everything and for any price, even from Jews. There was a market in town and the Jews went there openly to buy food stuff.

This situation was completely changed with the establishment of the ghetto. Even before, there were rumours that Jews were to be housed in the bombed building of the sugar factory “Konstancja”. There were Poles (among them Wiczichowski, the past leader of the nationalists and anti-Semites in Kutno), who warned their Jewish acquaintances and advised them to hide. Most Jews did not believe the rumours, but some left to town which did not have ghettos as yet, others hid in Polish homes, and gave them their entire possessions (among others, the Pole Kochanowvski had hidden Jews in his home). Before the Jews were enclosed in the ghetto, the wealthy families were jailed (among them the Kilbert, the Rabe and the Kronzilber families). They were incarcerated in the building of the Tobacco factory, their clothes taken off and left naked. After being searched they were beaten and all their valuables stolen, their homes confiscated and all that was inside taken. The prisoners were kept incarcerated until the formation of the ghetto; on the eve of the “Shavuot” holiday, June 16, 1940. The Jews were ordered into “Konstancja” in one day (though in fact, the move lasted 3 days), and permitted to take their belongings with them, except for their livestock. The town council had promised to supply wagons for the move, but gave only few, which caused a nasty fight among the Jews trying to gain space on them.

Increasing the bad situation, the German policemen were hitting severely the arguing and fighting Jews. Eventually, most of them had to walk, taking only what they could carry. The wealthy ones hired wagons and took all their belongings. The German policemen that accompanied the deported did not spare their blows.

In the “Judenlager Konstancja” were only a few halls with destroyed roofs and five one-story houses. Into those, the Germans had crowded more than 7,000 Jews that were then in Kutno. Some drastic struggles ensued for a place under the roof; only the strong or quickest conquered for themselves a corner to place a bed and lay their belongings. The weak and helpless were left with only the sky over head. On the first day a few had died from heart failure. The Germans enclosed the camp with barbed wire, and placed searchlights on top of poles. Day and night it was guarded by a close net of sentries, SchuPo (Schutzpolizei, municipal police) men, and guards.

In this present situation, the Kutno Jews made efforts to better their living conditions; those who were left roofless fashioned huts from furniture, erected tents from blankets, built primitive “apartments” and tiny cooking stoves from collected bricks, stones and found materials. In the whole area, there was only one well and three toilets. In the first days people stood in line for water from morning to night. The same was for the use of the toilets, and for that they had to pay five pfennigs. Within a few days a few more toilets were built, which were free for the users.

In “Konstancja”, a new Judenrat was organized (it is possible that this was the first Judenrat in Kutno). Bernard Holcman was elected as chairman, and for treasurer Alexander Falc. Members' names that are known are: Y. Kaplan and Ferdinand Kaufman from W.oc.awek. The Judenrat organised the food supply for the ghetto: bread (the authorities allotted 200 grams per person and per day), a bit of vegetables, horsemeat and skimmed milk, and they opened a public- kitchen for the poor. About the milk supply there is a unique story: Dina Kaplan, who had an agricultural farm near Kutno, got an extraordinary permission from the Germans to bring with her seven cows to “Konstancja”, and a special shelter was built for them in the ghetto. The Germans gave permission to one of the Jews to take them out for grazing in the pasture. It seams that this milk was given in the ghetto only to the sick and to the young children.

The Judenrat had a hard time in organizing the health services, as there were no physicians in the camp, but they received permission from the authorities for a Polish physician to doctor the ghetto's community. They also tried to bring a few Jewish physicians from other towns. In September 1940 the Judenrat had requested from the mayor of Lodz to send two physicians: a surgeon and a dentist, but he refused, explaining that there was a shortage of physicians in ghetto Lodz itself. The Judenrat had opened a small, primitive hospital in one of the ghetto houses, administered by Dr. Waynzaft from Krosniewice – a converted Jew.

For a time, the Kutno Judenrat received donation from the “Joint”, for the feeding of the poor and for medical care (in the second half of 1940, they gave 10,000 Mark and a few food items such as canned milk for the young children, and fat, given to the kitchen). At the end of November, the Judenrat received a 3,000 mark donation from the German Jews organization in Berlin, but that sum was minute, considering the daily expense of 800 marks the Judenrat had, while the income was 300 only.

A short time after the start of the ghetto, some of the people were employed by the Germans and so they were supplied with permits: loading in train stations, in military airport, and other places. This enabled them to smuggle into the ghetto some food stuff and heating material. The contraband and the smuggling business had developed soon and flourished, as they succeeded in bribing the German sentries with the help of Jewish agents. This way, it was possible for the Jews that were staying illegally in the “Aryan side” to enter the ghetto with the returning Jewish crew, and bring with them food.

Also, Poles would come close to the barbed wire, selling food and buying assorted articles from the Jews. Taking the cows to the pasture daily had made it easier to smuggle meat, as the bribed sentry did not notice that the returning cows were seven instead of the six that left the ghetto. The seventh cow was brought to the pasture by an organized group of Jews from the “Aryan side”, and also by Poles who dealt with smuggling meat. The ghetto even had some primitive coffee houses made from lumber planks. So food was available, but only the wealthy could afford it while most of the people did not have sufficient food to eat their fill and the majority in need of support was increasing.

As exiting the ghetto was easy, a number of wealthy families had escaped to other towns that had no ghettos, or those where the condition for making a living (mainly in housing accommodations), was better. The Jewish “go-betweens” (“makhers”) organized escapes for a heavy payment and bribes for the sentries. There were those who escaped in a wagon with their belongings. This was how a group of Jews from Kutno was found in Gostynin and when a ghetto was formed there they were ordered back to Kutno.

Under these – comparatively non-grievous (except for the most terrible housing) – conditions, the young people had organised cultural activities in Kutno, during the first months of the ghetto, characterized by entertainment and socializing. The “Bund” members and their sympathizers put on shows in “Konstancja”, which they called “Concerts” or “Live-Radio”. The performances' common subject was a satirical rendition on the relationships in the ghetto; first and foremost was a satire of the Judenrat, on the Jewish police, the administration clerks, the public-health workers, and the public-kitchen chefs. A large number of the people attended the performances with pleasure.

Another youth group from the intelligentsia circles, mainly those from previous high-school students, had fixed for themselves a “club” in the factory's tunnel, where they held cultural evenings almost daily. When a typhus epidemic started in the ghetto, they put on a play with the intention of raising money for a hospital kitchen. A former director from the Jewish theater in Wilna helped them by directing, but later the physicians forbade holding the event, in fear of spreading the epidemic. These young people also organised fund-raising among the wealthy, for the benefit of the poor youth. At the end of summer 1940, there were preparations made to activate a school and an orphanage, and the two youth groups helped in that. But the studies did not start because an epidemic broke out in the ghetto.

An outbreak of epidemic typhus was not at all surprising under the dreadful living and hygiene conditions in this ghetto camp, especially in the autumn when the cold forced the people who, up till now had been in tents and primitive cloth shelters, to move to the halls of the factory, in any case crowded. As mentioned, these halls had broken roofs and were not heated, and the rain and snow leaked unrestrainedly into them. Ten people lived there in each square meter. People froze and many even became sick with typhus. The German authorities feared that the epidemic might spread, closed up the ghetto tightly and hung a sign up on the gate: Danger of plague – entrance is strictly forbidden. The ghetto was officially declared closed. A special committee of senior German officials arrived to check the situation in Kutno. The mayor of Kutno replied to their words of criticism: “And what did you expect? This is just a death camp for Jews!” And so, there were times during the epidemic when the number of dead reached 30-40 a week. The Jews were not allowed to go out to work and this order made smuggling harder. Hunger grew greater. The “hospital” in the ghetto was full to capacity. Also the building meant to be a school was turned over to the sick. But even with this addition it was not enough and many sick people remained lying in the communal halls. Already in November 1940, at the start of the epidemic, the expenses of the Judenrat on the “hospital” swallowed up almost a third of its monthly budget. The Judenrat applied formally with a request for help to the mayor of Sosnowiec, who served as head of the Jewish communities of the whole area of Upper Eastern Silesia, but there was no reply. A delegation was sent to the Warsaw ghetto, and brought back a young doctor from there, Dr. Brzoska. Again, in January 1941 the Judenrat sent two delegates to Piotrkow Trybunalski (the exit permits were obtained by bribes). One of them, captain of the Jewish police of Kutno, came from Piotrkow. The aim of the delegation was to bring a doctor. The religious Jews fought the epidemic in their own way. In order to disinfest the purification house of the cemetery, the rabbis consecrated the wedding ceremony there of a pair of orphans. The Jews came in their hordes to this betrothal. The youth groups set up a kitchen in the hospital in order to assuage the hunger of the sick a little. To this goal donations were collected from the wealthy Jews and necessary foodstuffs were obtained from some smugglers. The girls laundered, cooked and guarded in rotation. In the spring of 1941 the epidemic increased and owing to the isolation of the ghetto the hunger of the population grew and their poverty deepened. In May 1941 most of the members of the meat smuggling group were arrested following denouncement. They were hanged in W.oc.awek. In the summer, when the bed of the Ochnia river had dried up, for some time food stuffs were smuggled into the ghetto via a tunnel connecting the factory with the stream. But the Germans discovered this method also and the smuggling ceased. However the number of poor people needing the communal kitchen increased steadily: In August 1940 this number was 1,102, and in March 1941 it was 2,340. Also deaths from starvation increased. In December 1940 until March 1941, 663 Jews died in “Konstancja”, of these 278 died of typhus. Everyone who found a possibility of escaping from the ghetto still did so until 1941. Especially when the rumour broke out that the paid guards and the auxiliary police would be replaced by SS members and the Mayor announced that the “Camp of Death” should be destroyed quickly. A number of Jews then bribed the guardsmen and found a hiding place among Poles in the neighbourhood. Some of them also went out to G.bin, to the small ghetto there. With the rising death rate and the flight from the ghetto, its population decreased: on 18.4.1941, according to the numbers registered by the Germans, there were 6,604 Jews, 5,239 local people and 1,365 refugees. And on 15.7.1941 there were in Kutno 6,015 Jews.

In this difficult situation the social injustice prevailing in the ghetto stood out. As noted, in the Konstancja factory grounds, apart from the halls, there were five single-storey residences. Occupying them were the offices of the Judenrat, the rest of the Jewish managerial institutions and also the hospital. In one house, jokingly nicknamed the “House of Lords”, the members of the Judenrat lived together with the wealthy and more influential Jews who paid the Judenrat hard cash in exchange for this right. Therefore the living conditions in this house were ideal compared to the living conditions of the rest of the inhabitants of the ghetto: in one apartment with a kitchen lived no more than three families. People would come to these fortunate folks in order to sleep one night in conditions better than their friends living in dreadful conditions. It is likely that this situation existed in more than one house. This matter caused envy and resentment. On one occasion matters got to a demonstration, and protesters took the law into their own hands. A crowd of poor people gathered next to the “House of Lords” and demanded that the treasurer of the Judenrat come outside. When he came out to them, they dragged him to the factory and hurled threats and accusations at him. The people attacked the treasurer and beat him. The German police, summoned by the Jewish police, rescued him and dispersed the crowd.

The last piece of information from the Kutno ghetto (a letter) reached the Kutno Jews living in G.bin in February or March 1942. This letter said that for two days empty freight trains had been parked inside the camp (the sugar factory was situated opposite the railway station and a branch track went inside the courtyard). The Jews did not agree to go up onto the trucks, although – so the writer of the letter wrote – it was not clear how long they were able to oppose the order. The Jews of Kutno were dispatched to the death camp in Chelmno from the end of March or the first part of April 1942. Only 213 Jews, living in Kutno at the outbreak of the war, remained there. A few of them returned to the town (in October 1945 there were 50 Jews). However, after a short time, they left the town forever.

Sources

Judea and Samaria region: 03/2318, 03/672, PH/33-2-1, PH/10a-2-2.

Y. Trunk, A Jewish Community in Poland at the end of the 18th century – Kutno, Warsaw 1934;

Mordechai Ben Shmuel, The King's Gate, Zolkwa 1762-1764. Vol. I, Part VI, Chapter IV.

Yizkor book of Kutno and Surroundings, Tel Aviv 1968.

“Einikeit” [Agreement] 9/10/1945; “Beit Yaakov” 1925, Num. 21-22: “Haynt” [Today] 13/3/1924, 16/6/1924, 30/4/1925, 10/2/1926, 8/3/1927, 2/7/1929, 14/1/1931, 26/3/1931, 24/5/1931, 1/8/1931, 9/11/1931, 10/5/1932, 8/9/1936, 28/10/1938, 8/5/1939, 26/7/1939; “Lodzer Tagblat” [Lodz Daily Newspaper] 12/12/1917, 20/2/1918, 7/3/1918, 17/6/1924; “Lodzer Volksblat” [Lodz People's Newspaper] 16/7/1915, “Das Neue Leben” [The New Life] 10/5/1946; “Neue Volks Zeitung” [New People's Post] 11/1/1928, 20/9/1928, 15/11/1928, 17/4/1929, 8/10/1929, 15/2/1932, 9/7/1933, 20/11/1933, 18/2/1935, 20/12/1935, 13/6/1936; “Nasz Przeglad” 13/6/1937; “Trybuna Narodowa” 10/2/1934; “Wiadomosci Codzienne” 5/9/1926.

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 6 Nov 2009 by LA