[Page 18]

Sports in Kremenets

A chapter of memories by Manus Goldenberg and Milek Taytelman

Translation by Theodore Steinberg

In the ancient village of Beit She'an, where I find myself, thank God, at my daughter's, a blessed stillness reigns. A couple of months ago, Katyusha rockets often passed overhead with an awful roar and in their wake brought death and destruction.

The surrounding kibbutzim and settlements can breathe easy and proceed with their daily activities outside bunkers where they used to spend their nights and, often enough, their days. On both sides of the nearby Jordan, one can see Israeli and Jordanian farmers calmly working their fields. Sheep and cows graze comfortably here and there. It's a kind of utopia that everyone wishes could endure. Between the hills of Gilboa in the west and those of Galilee in the east, the broad, green valley of Beit She'an is spread out, dotted with blooming Jewish villages that attract the eye.

On the eve of Independence Day, the holiday fills the air, and joy fills everyone's heart. This pastoral landscape that surrounds me makes me think of a far-distant picture. It was a spring evening; the last rays of sunset illuminate the local “ruins.” All is silent. On the fresh, fragrant grass of the mountainside, toward the town, a group of students from the local School of Commerce lie around and contemplate with pleasure the beautiful landscape. The sweet aromas of the trees reach them, as do the shrill voices of children who are ending their games, and the voices of their mothers, who call them to dinner. It seems as if their voices reach me here and mix with the voices that I hear at a distance in my little corner of Beit She'an.

These are the same children, the same mothers, and the difference in time and place dissolves. Are they perhaps the reincarnation of those murdered mothers and children?

In Ukraine, too, those bloody days ended, days that had been lived in panic through the three-year civil war. As if a volcano had erupted, the previously oppressed desire for an intense community life, for free movement, renewed communication with the Jewish centers in Galicia and Poland, from which we had long been cut off, burst forth.

[Page 19]

What followed was a golden age of Jewish community life in our town.

Now the group of students who were found every evening on Mount Bona had dreamed a dream of Zion since their childhood. Now they were taken by the suggestion of the teacher Yakov Shafir to start a Youth Guard chapter in Kremenets. But the Poles did not legalize such an undertaking. And when we began to undertake theoretical work to study the national revival movement and the development of the Jewish parties that were then active in Poland, we did so in the dark corners of Mount Vidomka, just as had been done years ago by members of the underground revolutionary movement in the city.

We knew that the Polish police were spying on us, so some of our activities had to be disguised as scouting, which consisted mostly of long hikes on foot to nearby towns and villages. The fields and woods on our way still bore signs of World War I and the civil war. Deep trenches were all over. Clumps of barbed wire lay everywhere–rusty helmets, pieces of weaponry, and human bones were all mixed together. Here and there stood a lonely, orphaned marker with a message from parents to “any passerby” to say a prayer for the soul of their fallen only son. And when we would pause by such a monument, no one thought that all this would be repeated in 20 years in a more horrifying fashion.

On one such excursion, we came to Dubno. There we came across a football match between the local Maccabee team and a military unit. This match proceeded with a certain solemnity. On all four sides of the dark green lawn stood a crowd, dressed in summery colors. The game was accompanied by the regimental orchestra. The solemn circumstances made a big impression on us, some of whom had never seen a football match. On the spot, we decided to form a football club in Kremenets, even under the auspices of Youth Guard.

Those “pilgrims” who saw the football match in Dubno, who saw how good it was, were the group of students who every evening gathered on the side of Mount Bona. Even the quiet, cool evening could not quiet their worries: there were too many obstacles in their way to carry out the Dubno decision. Where would they get a ball?

[Page 20]

Such a thing could not be found in our city. And there was not enough money in the world to buy the ground for a playing field. And where would people get shoes, uniforms, and so on, since we had no means?

How we overcame these difficulties is described in the Hebrew section of Booklet 7.

The chapter before this is Genilaye Aziyere, which for all Kremenetsers is closely associated with the best memories of our old home. Almost no one who attended the winter and summer sports competitions at the lovely lake knew that it was discovered by the first pioneers of Jewish sport in Kremenets. It was like the discovery of America. Often in Kremenets there were experienced travelers in the hills. But none of them managed to reach every Edenic corner. The pioneers, however, suggested the beginning of what became the Genilaye Aziyere that later represented Kremenets for many years.

With great effort and after many hesitations, the tentative founders prepared for the first match in Kremenets on a summery Thursday evening as the residents hurried to prepare for the Sabbath in their homes, as from every open window wafted the wonderful aromas of fresh challahs and cookies with cinnamon. Opposite Gindes's apothecary stood Moshe Hipsh. He tied his apron on his hips, divided his large beard into two points, and struck the sidewalk three times with his hard stick. “Adam himself fished here!” he began to call out, as was his custom. But this was wholly different Thursday. This time he did not call out about a “substantial fish” that was desired by Moshe Kraf, nor about a cask of “substantial herring” that belonged to Sore Freyde Tabatshnik, nor about the special Thursday sweat bath for the “substantial” women in honor of the Sabbath. This time, after a long pause, in a solemn style, he let it be known that on Sabbath morning, the Sabbath of the Torah portion Vayakhel, after kugel, God willing, all Jews should come to the Vidomka, where there would be a substantial football match between the substantial Maccabees and the “substantial” Russian team Yakar. “The substantial orchestra will perform.”

Early that Sabbath morning, a clear sky smiled over Kremenets. The Sabbath-observant world made their way to the Great Synagogue and the study halls; along the way they saw a large yellow banner on the wall of Vitel's store, Liora Gurvits's handiwork. It showed a football player lifting his foot, aiming at the ball.

[Page 21]

A few words in Polish were painted there regarding the upcoming match. Further on was a beautiful banner by the gifted young artist Koka Margolis. Both placards served us well for future matches.

On that Sabbath, many Kremenets Jews dispensed with their Sabbath naps and joined the stream of folks who flowed to the Vidomka and from there along the dark, woodsy road to Genilaye Aziyere.

Music resounded from the surrounding cliffs. People hurried. As they emerged into the light, they were struck by the picture that appeared before their eyes: the green field surrounded on all sides by thickly wooded hillsides bordered with many colors. The clear, fragrant air filled the lungs intoxicatingly. The gentle sounds of Russian waltzes mixed with the songs of thousands of birds and filled hearts with joy.

A shrill whistle from the referee cut through the air. Everyone became silent. The Russian squad Yakar trotted out of the woods, and opposite them came the Maccabees in their new blue and white uniforms made from Ayzik Shteyner's cloth.

Just as their uniforms fluttered in the light breeze, so did our hearts flutter. Everything was like what we had seen not long ago in Dubno. Our dream had come true. But could we justify the hopes of the Jewish spectators? Against us was that Russian squad, which included a couple of officers who had played football in the Russian army.

Another whistle from the referee. Then the game, the first public football game in Kremenets, began. We played with all our strength, knowing that the fate of Jewish sport in Kremenets hung in the balance. If we lost, people would not forgive us for their disappointment.

We won! It's not difficult to describe how the victory was received in the Jewish world. The joy and the excitement were astounding.

Thus ended, so to say, the debut of Jewish football in Kremenets. This was in the summer of 1921, exactly 50 years ago. After that, sport was an integral part of Jewish community life in Kremenets, and it became increasingly important.

[Page 22]

(See “First Maccabee Team” in Kol Yotsei Kremenets, number 7.)

Fifty years have passed since that cool evening in Genilaye Aziyere, but I can still sense the sharp, bittersweet odor of the grass and the bushes. I see how the shadows lengthened. The day gave over its dominion to the night. The happy crowd did not want to leave. My skin crawls when I see what they and their children would go through in 20 years.

A week after our first victorious match, I was with other players from our first team who were called to serve in the Polish army. For a long time, I was separated from the sports activities in Kremenets. But our Milek Taytelman came to my aid. He had a remarkable memory for life in Kremenets and for its inhabitants down to the smallest details, beginning with his childhood.

We were sitting in a café that was frequented by our editor and board. In the next room, people were watching on television various sports competitions from this year's world HaPoel [an Israeli Jewish sports association] gathering in Israel. One after another, familiar images from the intense Jewish sports world of Kremenets swam before our eyes. After that first match, our Maccabees went on the road. There were many similar teams. Players were recruited from them for the first team. Its new manifestation was stronger. Players from Rovno, Lviv, and Warszawa came to stay for a short time in Kremenets and learn the mechanics of the game.

In June 1923, they played against a team from the Rural School, the agricultural school in Belaya Krinitsa. In connection with that match, Milek brought up an episode that is engraved in the memories of all surviving Kremenetsers. The match had attracted a large crowd of Jews and Christians. There was a lot of tension. The match ended with an unexpected victory by the Maccabees. There was great joy among the Jews. But among the many young people who had come to Kremenets from all over Poland to study at the local trade schools, there was much anger, which they proclaimed with shouts. As the crowd began to move out, a neighboring boy–Yosele Trakhtenberg (who now lives in Argentina)–came running to me and breathlessly said that one of the students was yelling antisemitic slogans that had been used by the “Whites” during the civil war in Russia.

[Page 23]

I was then doing my yearly military service and so was wearing my uniform. I went with Yosele to find that hooligan. After searching in the woods and on the road, in that mass of people, Yosele pointed out a tall young man wearing a student hat. He was with some other tall people who, it seemed, were his sisters. Without thinking about it, I gave him two quick slaps and let him know that they were for his antisemitic shouts. The sisters started to scream, and the boy himself, along with his companions, was not silent. We were engulfed by the crowd. I did not see what was going on around me, but Milek told me that fights broke out along the whole road between Jews and Poles. People had sticks that they had broken off from fencing. Miron Gindes, who was known in Kremenets for his bravery, was a wonder. When the fighting mass entered open space that bordered Bikovski's dachas, waiting for us was Berye Liakh, a former Russian officer, son of a once-rich property owner. With him were his Russian followers. They plucked me from the crowd and protected me. It seemed certain that the gendarmes would arrive at any minute and arrest me. Berye ordered me to find a hiding place in the nearby courtyard of that enemy of Yisrael Bikovski. Unnoticed by the courtyard's inhabitants, I jumped through a window into a dacha and hid under a bed. Outside, the shouting went on for a while, Milek says–I was there the whole time. I saw how all the young butchers and coachmen, all the well-known fighters from the city, armed with clubs, came running from the city, and the beatings lasted until the police broke it up.

Later that night, my friends came to the Vidomka with a carriage and took me to the home of my friend Frishberg's parents, where I spent the night because the police were looking for me. Early in the morning I returned to my people in Krakow. To my good fortune, the head of the administrative office was a Jew (a rare occurrence at that time in the Polish army), and one of his aides was my friend Mendel Fishman from the Dubno battalion. Thus, when the report reached them about what had happened, along with a demand from the police in Kremenets, both documents disappeared.

[Page 24]

After my release from the military, I ran into Malski, who led the investigation and feigned sympathy. He asked whether my punishment in the regiment had been too severe.

That episode remained in the memories of Kremenetsers for many years. That was, it seems, the koshering of Jewish sport in the city. The competitions between nationalities were always fraught with tension and antagonism, but they again rose to such a level.

Milek remembered all the facts and people. They flowed out of him as if from his sleeve. This makes me think of a host of fond memories from that time, when we were both part of the many young people in Kremenets. We traveled for sport and breathed the air of life's joys, of youthful ambition, of healthy humor in the green summers and snowy, frosty winters.

We were full partners in the broad swing of Jewish football in the city, in the quick development of other forms of sport. We always had new sponsors from among the citizens, who supported us morally and materially. Outstanding were Ides Beleguz's son-in-law Epshteyn, Yankel Yaspe, and others.

A real achievement for us was the attention paid to our activities by Valentinov (who later changed his name to Vaynberg). With his stormy nature, his unflagging energy, his personal magic that opened everyone's hearts and doors, with his authority among both Jews and Christians in town, he helped us greatly and pushed us to accomplish ore. With his approval, we rented part of a field from Kaligovski and transformed it into a football pitch.

And with my friend Azriel Gorinshteyn, we took on financial responsibility, knowing that Valentinov would help us if we ran into trouble.

Our first match in the field, which we see in the picture, was against the Russian team from the Dubno regiment, Vega.

[Page 25]

|

|

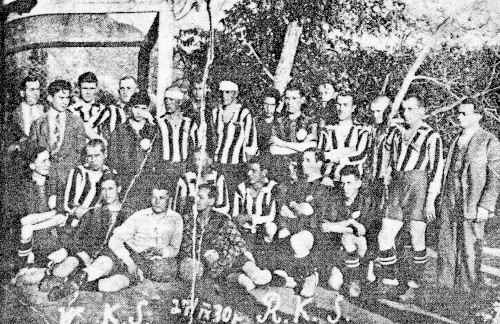

Summer, 1924. Match between the Russian club, Vega, and Maccabee.

The identities of those marked with a minus sign are unknown.

Standing, from left: Sashka Mandelker, Sashka Das, Nisye Segal, Liume Shnayder, Siunye Baytler, Misha Rabinovitsh, Kobrin, Pinye Bukhbil, Sergey Kamayev, Ilyusha Zakharov

Sitting, from left: Toran, Pesach Mandelblat, Leybchik Sher, Borke Matrokov, Pepka, Manus Goldenberg, Shonye Rish, Azriel Gorinshteyn, Vodonos

Lying, from left: Yakov Chasid, Avraham Bitker (in Leybchik Sher's arms–Berel Yaspe's son Liusik, who now lives in America.) |

An important sporting even in Kremenets happened in the 1925 football season. We took a pretty bold step. We challenged one of the best football teams from Lviv, Amatarzhe, for a Sabbath and a Sunday. The prize was the total receipts plus some extra.

The sensational news spread quickly in town. The Maccabee team, strengthened with younger players, began anxiously to prepare for the competition.

On Friday afternoon, amid holiday-like tumult, the players from Lviv were brought from the train station. We put them in the Pasazh Hotel. They ate at the Odzialavke. We promised to pay after the two matches. All the preparations were made. Posters were pasted around the city. Interest in the coming matches was growing.

And then what we feared, happened. On Friday night, thick clouds filled the sky, and on Sabbath morning the skies opened. It poured the whole day. The posters were washed away. The clayey water channels from the hills, as always in such cases in Kremenets, flooded and cut one off from Sheroka Street.

When we had to go over to the Pasazh, we found the players very depressed. They sat confined in the hotel as if in a prison. But we were even more depressed.

[Page 26]

We could not even talk about playing, and there was no prospect for the next day, Sunday. And in the back of our minds, we worried about how we would pay our debts. Only a miracle from heaven could save us. And the miracle happened. On Saturday evening, as the church bells announced to the Christians the news of the coming Sunday and to the Jews the departure of Sabbath, a strong wind began to blow. The skies cleared, and everything quickly dried up. Early in the morning the beautiful sun lifted everyone's hearts.

|

|

Match between Amatarsze Lviv and Maccabee 1

We present the names of the Kremenets athletes, who wear white shirts with blue stripes

From left: Pinye Bukhbil, unknown, Shayke Kapuzer, Mashke Margolis, next to him Binyamin Vaynberg (Valentinov), Mishe Rabinovitsh, Nisye Segal, Yisrael Goldenberg (who fell in the Land of Israel in 1929 in a battle with the Arab bands), Azriel Gorinshteyn, Ukel Benderski, Avraham Margolis, Frits Tsvik, Yisrolik Grinberg

Sitting, from left: unknown, Liume Shnayder, Shlome Lerer, Manus Goldenberg, Sunye Baytler

Lying, from left: Avraham Bitker, Motke Chirge, Srulik Fridman, Yoske Kroyt |

In the afternoon, everyone streamed to the playing ground. The wet, clayey road stopped no one. At the ticket office, a table at the entrance to the field, people bought the relatively expensive tickets.

The fence surrounding the field was barbed wire, and people could see the game from outside without paying. The police commandant came to help us. At Valentinov's request, he sent a mounted policeman to every match. He rode around the field while the game was on. This time he sent several. Consequently, we had enough income to cover our expenses.

It was a friendly match. Our guests showed what they could do, but their strength could not equal ours. Our players made the greatest effort to score a goal, and they tied it. This time Kremenets saw a superior game. It was a valuable lesson for the Maccabees.

[Page 27]

From that point on, the qualifications of our team grew. Our first team grew stronger through two good players from Warszawa and through Helman from Lviv.

|

|

The team after the match with the Amatarzhe

Standing, from left: Liume Shnayder, Yakov Chasid, Mashke Margolis, Mishe Landsberg, Motke Chirge, Mishe Shnayder (Karal), Betya Kapuzer, Yoske Kroyt, Yisrael Goldenberg, Shlome Lerner, Avraham Magolis, Avraham Bitker, Frits Tsvik, Nisye Segal, Pinye Bukhbil

Lying: Yisrolik Grinberg |

In time the Maccabees, which then were called the Hasmoneans, were enrolled in the third Polish league. This consisted of Jewish and Polish football teams that had a decade-long history.

Of the important football events inn Kremenets, people could remember the road trips of the Rovno Hasmoneans throughout Poland, with the great players Asherke Bik, Sovitski, Ford, and others. Passionate football fans, whom we have already mentioned, supported Jewish football in the city and thus helped them reach higher levels.

In 1929, through the initiative of the Jewish professionals union in Kremenets, the Yutshnia sports club was established. Several labor leaders in the town were devoted to it, led by Bund activist Shmuel Vodonos.

Several good players, former sportsmen and gymnasts, transferred from the Hasmoneans to the Yutshnia team. It was no wonder, therefore, that soon after its inception Yutshnia appeared as one of the strongest and ambitious teams. It had many outstanding victories.

[Page 28]

|

|

Match between the workers Yutshnia sports club and the 12th Ulan

The Ulans are wearing shirts with light white stripes

Standing, from left: Shonye Rish, Shmuel Vodonos, Kagan, Abrashke Rays (on his left stands the famous-in-Kremenets quartermaster Butshek, with a white scarf on his head), then Landau, Nate Kiperman, Yoske Burbil. The man wearing the suit is one of the directors of Yutshnia, not a Kremenetser |

At that time, matches took place at the football field in the old park of the former School of Commerce, 20 minutes from the city center. The number of spectators increased to be like those in other cities. Often, when there were major matches, the town itself seemed empty. One could say that the competitive, proud young athletes inspired the whole Jewish population with their ambition, making their hearts beat more strongly.

Together with football, all other sports also developed in Kremenets. The Lyceum, with its sports teachers and athletes from every corner of Poland, served as guides and inspiration to us.

Rich with experiences and dramatic moments were those competitions and races, winter sports and swimming. But that is for another time. Then we will again breathe the air of that vital, young Kremenets, its pride and its athletic accomplishments.

* * *

The valuable photographs that we print with this article are from the collection of Avraham Bitker, of blessed memory, and provided by his sister Fanye.

[Page 29]

The Bright Blue Sky over Kremenets Turns Black!

Duvid Tsukerman

Translation by Theodore Steinberg

As it says in Akdamut[1], if all the skies were paper and all the seas were ink, there would still not be enough to describe all the misfortunes, the horror, and the suffering that the German murderers brought upon world Jewry and on our beautiful Kremenets.

For 28 years people have described those misfortunes, and even so, much remains unexpressed, because one would have to have extraordinary talent as a writer to present the circumstances and describe the inquisition that the murderers imposed on Jewry. Who could show that the beautiful, blue sky could turn black with sorrows? Who could show that the sun could shine and simultaneously be clouded over for a portion of humanity–for Jews? “The sun shone, the blossom burst, and the slaughterer slaughtered” (Bialik). Who could describe how the sidewalks were made for all but not for Jews, how the Ritsku, the filthy gentile who used to clean dirt off the graves, could have the right to walk on the sidewalk while Jewish citizens, intelligent Jews, including the town rabbi, could walk only in the middle of the street?

All of this happened only a quarter of a century ago, and though we have become a free, proud people, we can never forget each day of Jewish misfortune, and it must be passed on from generation to generation.

The entrance of the murderers into Kremenets. The pogrom in the Dubno road and the prison courtyard. They dragged Jews from their homes and forced them through the city to the prison, beating them with whatever they could. And if in Jerusalem there is a Way of Sorrows, it is nothing compared to the Way of Sorrows that these victims, the Jews of Kremenets, traversed from the city, through the Dubno road, to the prison, where their ransom was death. And those who managed to escape were psychologically broken.

Life in Kremenets was horrible. Every day new edicts. Every day new restrictions and abasements. Not to go on the sidewalk, not to go shopping in the market. First a band with a Star of David on the sleeve, then two yellow patches, one in front and one in back.

[Page 30]

Early every day there was an assignment from the Judenrat to slave labor from which no one was certain to return. Every day, terrible news. And every day the telephone or the newspaper brought bad news. They killed Avraham Brik, our neighbor; they killed Rozen, the engineer. All of the intelligentsia arrested in Tivoli. One could go crazy from these reports.

Every day the families ran with parcels and begged the killers to give them to their relatives. The inquisitors took the parcels, even though the detainees had long before been shot at the Mountain of the Cross. The Gentiles who used to come from the village through the Mountain of the Cross brought us the sad news.

Every evening at 6:00, the doors and shutters were locked, and no one could step outside. Lucky were those who lived with a communal exit or a common room. After 6:00 they could at least sit together; but those who lived alone or with a solitary exit had to remain alone with their terror, with their grief, and listen to the constant tuk-tuk of the killers' boots, never knowing if someone would shoot them through their closed window, a nightly occurrence.

Every day, new decrees: deliver 200 fur coats, Jews must bring their gold, silver, and jewelry.

Who could present the ways a people could be terrorized, debased, so that they could more easily be despoiled of their gold, their silver, and their fur coats, even though they were tarnished by theft and robbery?

I will never forget the night when they burned and destroyed the Great Synagogue. The sky was red, and all night one could hear the explosions, because without them they could not destroy the strong walls.

Early the next day, as we went to labor with a group of 40, we went by the synagogue. We all stood and mourned over the destruction–the Kremenets study hall. Even people who had never crossed the threshold of the synagogue were weeping. It was a terrible sight: roofless, ruined walls, blackened by the fire–everyone wept. The sky was dark with clouds, because the ruins of the synagogue embodied the sorrows of Jewish Kremenets' tragedy. I was quite attached to the synagogue. For many years, with my father, of blessed memory, I sang along with the greatest cantors.

[Page 31]

Life became more and more difficult. The young sought ways to flee Kremenets, because there were reports that the Russians were not far away. But this was all made up. The Russians actually put up no opposition. The situation grew worse from day to day.

People sold whatever they could to get through a day. The peasants from the villages would come with robbery in their hearts and buy the nicest things for a tiny bit of flour or produce. The Judenrat did whatever it could to organize help for the population. It opened a kitchen that was a great help. The soup provided twice a day helped rescue many people from the shame of hunger.

Once, in February 1942, I was seized in a police raid in the street. Together with many others, I was taken to a work camp near Vinnitsa. French, Romanian, and Czech Jews were also there. From there I fled with two Jews (one from Lodz, Yakov Lasker, and the other from Kalish, Mikhel Kaplan, both of whom had taken refuge in Kremenets) to the underground movement Iskra, which conducted violent activities in different parts of Ukraine. Dressed like German soldiers, we were sent on a variety of missions, for which we received awards from the Russian army. Once my companions and I were captured and we were about to be hanged, but partisans from the Lassaveyer Woods took us and seized the city of Pavlograd, which later passed from side to side until the Germans completely destroyed it.

At the end of 1943, I became part of the Russian army. From there I went to the Polish army, 4th Division, with which I fought to Berlin.

Later, in Russia, I wrote about the activities of the movement in a special pamphlet.

Finally, in 1945, I experienced the day of victory over the German killers.

Translator's note:

- Akdamut is a liturgical poem recited annually on the Jewish holiday of Shavuot. Return

[Page 32]

Memories of our Old Home

Yitschak Vakman (New York)

Translation by Theodore Steinberg

The Old Study Hall

I immerse myself in thought, memories from our old home. We lived directly across from the old study hall, there were the Zvihiler Rabbi, Rabbi Velvel, of blessed memory, prayed. Our synagogue had no women's section–it was the only sacred spot in the city without a place for women. I remember one holiday when Itsi the sexton carried a burning light through the streets, because the gentile girl had not come to extinguish the light and he was waiting for the wind to do it. I used to come early to pray–I was saying Kaddish for my dear mother, peace be upon her. Among the first Jews who arrived for prayers was a short fellow–Manus Taker. I loved standing next to him and hearing him pray. He parceled out the words as one parcels out pearls–separating each word, each letter. He did not have much book learning, but his praying was a wonder.

Ayzik Shlisele (an Example of Stinginess)

Ayzik Krants was our neighbor. People called him “Ayzik Shlisele”–that is, he would take money from the usurers and pay in weekly installments. It was said that he came from the family of the Dubno magid, of blessed memory, a short man with a hump, a distinguished scholar with a sharp mind and a sharp tongue. It was said that he once went with a young man–a new son-in-law who came to borrow money. As they went, Ayzik smoked a thin cigar. He used to divide an ordinary cigar into three parts and smoked very thin ones. The young man took out a Rotshke cigarette and lit it with a match. R' Ayzik turned and made an excuse: he remembered that he had to be somewhere else. He would see the young man tomorrow.

On the spot he had decided not to give the young man a loan–he saw that he could not be trusted. “He saw that I was smoking, and he could have lit his cigarette from mine. He could have used mine and not whipped out a match.” His son Berel (Bush) once broke his foot. When Dr. Litvak told him what it would cost, he did not want to pay. Only after his wife cried bitterly did he return to the doctor to help his son. Meanwhile, the child waited in pain and anguish.

[Page 33]

R' Matis Chazan

I still have memories of my father-in-law R' Matis Chazan, of blessed memory, the kind of person, whole and upstanding, who is seldom seen. About my father-in-law, people said he was wealthy and therefore should not be paid for his cantorial services. I know that he was far from wealthy–and more than once he missed that salary, though he never said so. He made do, but he never spoke about it. His home was open to all, and anyone who wanted could come there for a meal. This was true for everyone. Together with Blumenfeld and Tsizin, my father-in-law supervised the Talmud Torah teachers. My father-in-law had to suffer greatly in paying the teachers–but it was more difficult to dismiss a teacher who was not suitable. He took a great deal of abuse from the teachers' families, but he never responded. He just went quietly away. My mother-in-law would often say, “Why didn't you answer?” and he would say, “When he got home, he would regret what he said to me.” My father-in-law was a Kohen. I never remember seeing him angry. He had a good reputation and was beloved by all who prayed in the Bedrik Synagogue. He earned his reputation through his purity, his beautiful way of conducting himself. In our old home he was one of the rare figures that I have encountered in my life.

Book of Vishnevets

Duvid Rapaport

Translation by Theodore Steinberg

When I was in Kibbutz Ma'anit on Shavuot, my good friend from Vishnevets, Moshe Shteynberg, lent me the Vishnevets volume[1] put out by the Organization of Immigrants from Vishnevets in Israel with the help of their landsmen in America.

This book is an important monument, a written marker for a small shtetl. Dear beloved Jews, good, generous people who were mercilessly slaughtered by the German barbarians with the help of Ukrainian murderers on the accursed Volhynian soil. Kremenets and Vishnevets were like a home with an alcove. Our home in the Vishnevets Road was the Vishnevets entryway. I remember as a child the graceful Vishnevets contractors, waggoneers, merchants, teachers at the Kremenets gymnasium, brides and grooms who came for bridal clothing–they stayed with us overnight and filled our home with tobacco smoke, words of Torah, conversation, clever jokes, joy, and laughter.

[Page 34]

So went life in a little shtetl until the bloodthirsty rage of the inhuman ones played out and swept it all off the face of the earth.

The book opens with a detailed map of Vishnevets, with all the institutions, streets and paths, butchers and boulevards, synagogues, zones and gateways indicated. The book is full of depictions of people–too few, to our regret–who miraculously escaped from the bloodbath as well as emigrants from Vishnevets who left their home before World War II. A terrible shudder seizes your heart, your soul, and leaves you feeling broken. The fluent, folksy Yiddish pervades every limb with the well-known Vishnevets landscape and familiar people.

The book has many pictures. It is a shame that the editors did not provide names for the people in the pictures.

There was shtetl with Jews–the book honors their memory. May their memory be a blessing.

Translation editor's note:

- For a translation of this yizkor book, see https://www.jewishgen.org/Vishnevets/Vishnevets.html Return

Images of the Past

Yitschak Trakhtenberg (New York)

Translation by Theodore Steinberg

Tovye and Sender Shepsel's[1]

The winds of freedom that began to blow over Russia soon after the Russo-Japanese War had a great influence on internal Jewish matters. For us in Kremenets, this took the form of a revolution against the community leadership's power and trustees, along the lines of Mendele Mokher Seforim's “tax farmers.” This revolution was led by two very energetic young people, Tovye the leather-cutter and Sender the egg man. They both proceeded to organize a voluntary “bed carriers fellowship” instead of the moribund, old-fashioned burial society.

Community matters were conducted by powerful Jews, while the people were silenced. Tovye and Sender formed not a small group but a people's movement. The workers–all of them: turners, carpenters, tailors, shoemakers–all became comrades. Thus began a new epoch in Kremenets. The “people” came together through unity and cooperative labor.

[Page 35]

At that time, epidemics raged everywhere: typhus, influenza, and others. Poor people died en masse, and there was no one to give them a Jewish burial. One of the principles of the society was that deceased could have a minyan from the society. This was called a “queue.” The secretary was the “writer” Itsi Maneles. He would call together a “queue.” When the eligible citizens saw that the society did so much, they became trustees and gave money. Meanwhile, the activities of the society increased, and they collected charity for institutions: Ekdish, the old people's home, the hospital, the charity fund. The headquarters of these activities was in Tovye's workshop. Nor did they neglect spirituality. The society presented Torah scrolls to synagogues. On a mild winter evening, in an apartment on Pritsesher Street, they would celebrate the new Torah. The whole city participated. From there they took the Torah scroll under a canopy, with a klezmer band, to the synagogue. The society celebrated along with everyone else. On Simchat Torah, the society celebrated at decorated tables. There a carpenter (I don't remember his name) expressed the sentiment of everyone with the following repeated cry: “The kahal is a great fellow! The kahal is a great fellow!” Sender used to go to the villages to buy eggs, and he would drink those eggs that broke. He had a voice like a lion. And at happy occasions he would sing the songs he would use to call peasant girls together in the fields. When he sang, the effect was like thunder.

They bought off a bit of land near the cemetery, and on a certain day the society came with a crowd to make a toast.

Once I was in a field with a friend and we searched among the old graves. We found Yitschak Ber Levinzon's grave. The monument was small, almost ruined, and one could barely read his name.

At all meetings and community gatherings, the society was represented by Tovye and Sender. They were our pioneers in the city in the area of multibranched social aid for the people's self-esteem.

Honor their memory!

Fishele the Porter

Curious, dried up, with a nice face, Fishele used to stand in the market, tied with a dirty rope, and wait. When the wagon would come with big, heavy chests and packages, the porters group would make a ruble.

[Page 36]

But Fishele was not one of them–not with his strength. People would see Fishele with a five pood [a Russian weight] sack of flour (twice his own weight) on his back, bent over and pulling, barely moving his foot.

“That, too, is a porter,” people would laugh. Fishele knew how to read a sacred book and to read Torah n synagogue. On Sabbath, Fishele would always leave the study hall with two companions and gesticulate as he considered a difficult question. The Jews wished him, “Good Sabbath to you, Fishele, good Sabbath.”

Original footnote:

- In my childhood, Tovye Shpigel (Shaykovski) aroused great interest and enthusiasm with regard to his many activities, which were often combined with charitable deeds (especially in the civil war years). My feelings for him and his aid activities were published in the Hebrew “Alterman's Courtyard,” which appeared in Pinkas Kremenets, published in Israel, pp. 166-267.] Return

In Memoriam

Eliezer (Luzer) Brik, of blessed memory

Rachel Geva-Brik (Sdot-Yam)

Translation by Theodore Steinberg

It is impossible to describe and discuss my father, Luzer Brik, of blessed memory, without going back to his city of birth, Kremenets. There was the source of his love of labor, his love of life.

From his stories and those of his many friends, we (his daughters) absorbed a love for that city and its people.

It then seemed that we ourselves came from there, together with all those who visited us and who even lived with us.

He was born on 1/12/1898. His father was Berish–Beyle Berke's Brik, and his mother was Sore (Surtshe).

His father, Berish was a locksmith, an artist in his craft. From his workshop on Sheroka Street he earned a good living for his family. He had a good lineage and was a prayer leader with a developed musical sense and a pleasant voice.

[Page 37]

On Sabbath or holidays when he led the prayers in Hersh Mendel Roykhel's synagogue, young people would listen to his melodies with great pleasure.

Luzer (Luzke) was the youngest son and the darling of the family–but he was not naughty. He loved to laugh and amuse. He was not in school for very long. He had to join the father in working at the locksmith business. There he absorbed his love of work. He took seriously the verse, “Love our labor!”

When he got older, he opened his own workshop, and among the various things he worked at, he would make sleds for children. Many of his patrons were “scamps.” Along with their order he would give a free gift: a little song, a charm for good sledding. This is how the song went that the gentile would have to sing aloud:

Laugh–laugh–gentiles blow

Jews blessings–gentile fevers.

Not understanding the words, the gentile would earnestly rush out to do his duty: to sled while singing the chorus…

The workshop was always full of neighborhood children, who were drawn to him.

With pleasure they watched him work as he transformed a simple iron wire into remarkable, beautiful shapes.

In 1923 he immigrated to Israel with his family and settled in Tel Aviv. He needed no help. He did it all by himself, and in a short time his home was transformed into an “absorption center.” Scores of Kremenetsers coming to Israel spent their first days at his home, and he helped them with advice or, more than that, with getting things in order.

Luzer soon created a workshop, because he said, “I can't work for anyone else.” “I trust only my own two hands. They earn my living.” He loved every bit of work, and it was hard for him to stop.

“In the mornings I love to think about my work–just as my father, peace be upon him, did.” A workman–an artist. An iron fence, a shutter for a gate–nothing out of place. He made everything beautiful: a flower, a leaf, just as his imagination directed.

[Page 38]

He was no scholar, not even very good at Hebrew, but he loved to hear learned people, and he followed the saying, “Sit in the dust at the feet of the wise” [Pirke Avot 1:4].

Thus, he knew a great many verses by heart, and he mixed them into his everyday conversations just like Tevye the Milkman.

When Dan, the youngest of his grandchildren, did not know what to do with his Chanukah gelt, he gave him this advice: “Buy yourself a friend. Short and sweet.”

The children, his grandchildren, loved him totally, and he himself was like a child with them.

All three of his daughters joined different kibbutzim. That was far from his ideal, but he accepted it with understanding and love. He visited them often and felt at home there.

When he was working, Luzer would sing bits of cantorial music. On Sabbath he was prepared to walk even to Petach Tikvah or Ramat Gan to hear a cantor that he admired.

Every Sabbath afternoon he would go to Ohel Shem to hear cantors with their choirs.

During his last years, his eyesight declined, but even then, he never lost his verve and humor.

Every day as he made his way to synagogue, the children would introduce themselves: I am Yosi, I am Dani, and so on, because they knew that although Grandfather Brik could hardly see them because of his eyes, he could feel them in his heart. He gave them lollipops, and they led him to daven.

Three times I saw my father cry: when his mother died, when it was announced on the radio that Kremenets had been taken by the Nazis, and when he sold the workshop that he had brought with him from Kremenets. He sat alone and cried.

He died on Purim in 5731 [1971].

Yiddish translation by Rachel Otiker.

[Page 39]

Yitschak Barats, of blessed memory

Yehoshue Golberg

Translation by Theodore Steinberg

On Thursday evening, June 3, 1971, a number of Kremenetsers gathered in the Levinzon Library to honor guests from Canada, Fayvel Barats and his wife. With them was Itsik Barats, Fayvel's older brother, who shared equally the moving meeting with our landmen. On Friday evening the two Barats brothers were together again, this time in the home of Aba Kneler in Ramat Gan, with another pair of Kremenetsers. On going home, Itsik felt ill, and shortly thereafter he died in the hospital.

The Barats family was known in Dubno for its open home and hospitality. All of the sons aided their father, R' Yisrael Barats, in his lumber warehouse.

After the outbreak of the war in 1941, Itsik, after extensive wandering, arrived in the middle of Asia, in Alma Ata, where he worked in a sawmill. There, too, he met his future wife, Chasye.

After the war they settled in Szczecin, Poland.

In 1948, Itsik, with his wife and his daughter Miryam, came to Israel and was one of the few immigrants to settle in Yehud. There he tried his luck in the lumber business. Thanks to his good business sense and his good relationships with people, he earned a fine reputation and a large clientele. The old Arab hovel where he first settled was transformed into a large land comfortable home.

Itsik was beloved by all the inhabitants of Yehud. He made time for everyone who came to him. One would ask for advice, a second for a handout or security for a bank loan. He also frequently made secret gifts.

At his funeral it was obvious how much he was loved. It was a sad day in Yehud: merchants closed their stores, the council chair participated, as did the officials of the bank and members of the local police. There was a spontaneous demonstration of final honors for a man whose ideals had brought him such a reputation.

Itsik was 61 when he passed away. He left his wife, daughter, grandson, son-in-law, and a son in the Israel Defense Force.

May his soul be bound up in the bonds of eternal life.

[Page 40]

Klara Shnayder, of Blessed Memory

Shmuel (Milek) Taytelman

Translation by Theodore Steinberg

An outstanding woman from Dubno. Her husband, Moshe Shnayder, of blessed memory, was a grain exporter. Their home was always open to everyone. The refugees from World War I in Kremenets who came from Russia naked and barefoot found succor in their home.

At the beginning of World War II, the Shnayder family was thrown into the broad expanse of Uzbekistan. There, too, at that difficult time, those in need found a refuge in their home.

After arriving in Israel, the Shnayder family settled in Rehovot, with their daughter-in-law and grandchild. A few years later, their son arrived from Russia with his wife and two children.

In Rehovot, too, Klara was beloved in her circle.

Our landsmen, meeting her on joyous civic occasions or at the memorial for the martyrs of Kremenets, treated her with great respect and friendship.

Klara died on 3/19/71–suddenly, in her sleep. She died quietly not disturbing anyone even in her final moments.

Klara left behind a daughter-in-law, a son with his wife, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren.

May her soul be bound up in the bonds of eternal life.

Eliyahu (Eli) Shifris, of Blessed Memory

Manus Goldenberg

Translation by Theodore Steinberg

On January 26, 1971, Israeli radio and newspapers announced that a terrible catastrophe had occurred on the road from Beersheba to Tel Aviv. In a collision between two cars, one of them, a private vehicle, was destroyed and the driver and two hitchhikers, soldiers, were killed.

The driver was Eliyahu Shifris, the son of Gute and Yosef Shifris, 22 years old.

[Page 41]

Gute and Yosef Shifris immigrated to Israel from Poland in 1958 with their two children, Eli and his younger sister.

After finishing his schooling, Eli worked as a mechanic in an automobile company.

During his military service, he served in the Six-Day War as a sergeant. He fought in Arab East Jerusalem and in the Golan.

When he returned home, the automobile firm named him its chief salesman and gave him one of the firm's automobiles. He was on a business trip when his tragic death found him.

Eli was supposed to be getting married. From his and his wife's earnings he bought an apartment in Ra'anana, where they were supposed to live. There was a room there for his parents.

With Eli's death, his parents lost a good and treasured son. From their conversation, one can see that in his brief life he gave them much pride.

May his memory be a blessing.

Binyamin Barshap,

of Blessed Memory

Yitschak Vakman

Translation by Theodore Steinberg

A few words over the fresh grave of our Binyamin Barshap, peace be upon him.

I knew him since 1943 when I became a member of the Kremenets Society in New York. This was in the war years when I received many letters from our brothers in the camps in Germany. We decided to start a relief committee, and I was given the honor of being chair. I then had the opportunity to work with Binyamin Barshap, of blessed memory, which gave me much pleasure.

[Page 42]

There was not a single meeting of the committee that he missed. He was always among the first there. We used to go together to the Bronx restaurant of his father-in-law, Isidore Zalmanovitsh. After reading the letters from our landsmen, Binyamin Barshap, of blessed memory, was the first to participate, for he felt that every meeting should have a concrete outcome. He was a person, a carpenter with little training in Judaism, but he had read a great deal of Jewish literature. Some years later he told me a bit about his life. He felt then that his days were numbered. He said, “It is a shame that I didn't go back three years, because in recent years I have suffered much, particularly because of my noble wife's illness.” Although ill himself, he devoted himself to his wife, to whom he was so close.

Binyamin was loved by his friends and customers as a good workman and a fine man. He distanced himself from anything improper–I never heard a crude remark from him, nothing that was not upstanding. At meetings of the Society, which he himself had established 55 years earlier and of which he was several times the chair, he would always speak sparingly and tactfully–counting his words–not showing off, but to the point.

A conflict between Binyamin Barshap and the Society over a family plot in the cemetery caused him great agony after he had given so much to the Society, supporting, as he had earlier, the needy landsmen everywhere. He did not part from the Society that he had so long supported. Later, when our townsman Yisrael Mandel from Kremenets wrote to me about the need to put a fence around the common grave of our city's martyrs, the Society gave $150, and we each gave the remainder. He went with me to buy the packet that we sent, and this enabled them to erect a barrier around our brothers' cemetery. Six days before he went to his eternal rest, Binyamin sent for me via his daughter. I went quickly to the hospital, where he said this to me: “Since I will soon no longer exist, my daughter will give you a certain sum ($500) for the Society in Israel.” Also $100 in charity he had long given to maintain my son-in-law, Rabbi Yosef Karasik, who should speak at his funeral, and another $50 in charity for another rabbi. This was our landsman, Binyamin Barshap, peace be upon him.

[Page 43]

This was a man of an unblemished character, 86-year-old Binyamin Barshap, of blessed memory, “the father of the Kremenetsers,” as he was called years ago by all the “green” Kremenets immigrants to whose help he came after offering them a roof over their heads for their first days in America.

Let him not be lost or forgotten.

Honor to his memory.

Moshe Vayner,

of Blessed Memory

M. Goldenberg

Translation by Theodore Steinberg

Moshe Vayner, son of Eliezer and Shifre, was born in 1912. His family lived in Dubno. Like most of the families there, they were industrious, friendly, and generous.

With the outbreak of the war, Moshe, like many other Kremenetsers, fled to Russia. There he was mobilized in one of the workers' battalions. He went to Tashkent and after the war was repatriated to Poland.

Moshe made the heroic journey on the famous ship Exodus. After arriving in Israel, he enlisted in the Haganah and fought in the ranks of the Israel Defense Force until the end of the War of Independence.

In 1949, Vayner got married.

Until two years ago, when he was struck with his fatal illness, he worked as a building carpenter.

After long struggles, Moshe Vayner passed away in January 1971, leaving behind his devoted wife Klemantin in deep sorrow for her deeply beloved husband.

May his memory be a blessing!

[Page 44]

Miscellaneous

Duvid Rapaport–On his coming to Israel, a hearty welcome, and although it is not certain that he will stay with us, he has already participated in editing Kol Yotsei Kremenets.

Rapaport has been active as secretary in the Society of Kremenetsers in New York for many years. He has also done much to distribute our booklets and has from time to time contributed to them.

We receive him as a member and co-worker with open arms and wish him health and an easy transition to our country and its inhabitants.

After a few weeks at Kibbutz Ma'anit, Rapaport has taken a place in Tel Aviv.

* * *

Among our veterans–On the 50th anniversary of the Pioneer immigration from Kremenets, a collection of the remaining members from the first Kremenets settlement gathered on 2/8/71 at Shlome Poltorak's in Tel Aviv with their families and a few good friends. They spent the evening reminiscing about those distant times.

Member Rokhel read a letter from 1921 to his parents in Kremenets, a week after his arrival in Israel, the writings of a young pioneer, his first steps in Israel, and thoughts about his future–a document that reflected the reality.

Member Poltorak told humorous stories and sang songs from the “creation day.” Member Manus poured out his bitter heart about why people then rejected him for being too young so that he had to stay in Kremenets until 1933.

For our part, we say to our veterans: “Blessed are your advanced years that are not ashamed of your younger years.”

[Page 45]

The Golden Wedding Anniversary of Yakov Shafir and his wife Chane (née Poltorak)–was celebrated in January 1971.

Here are a few details from his biography. Together with his brother-in-law Bozye Landsberg, Shafir was one of the leaders of the Zionist organization in Kremenets.

Born in Dubno, after his father's death in his early childhood he was raised by his grandmother Tsviye in Kremenets, where he learned about poverty and want. But thanks to his diligence and energy, he made it to the Vilna Teachers Institute, where teachers for the government Jewish schools were trained. After graduation, he spent some time giving private lessons while working as a teacher in the former Hebrew School in Kremenets.

When the Tarbut schools began, he transferred there in Kremenets, following service in Zwierze and Ostrów Mazowiecka as director of the schools there.

During World War I, when he served in the Russian army, he became a member of the committee of Zionist soldiers in Minsk.

Returning to Kremenets, he became active in the Zionist movement, as well as in overall Jewish community life.

At the time of Petliura, and also of the Bolsheviks, he spent time in prison together with Bozye Landsberg, Dr. Litvak, Goldring, and other Zionist leaders.

In 1938 he immigrated to Israel and settled in Tel Aviv, where he was accepted as a teacher in a special school for children with delays.

Together with Rive Berenshteyn, of blessed memory, Manus Goldenberg, and Leyb Kotliar, of blessed memory, he was one of the founders of the Organization of Kremenets Emigrants in Israel, and for a while he was very active. Only in his last years, because of health concerns, did he take a passive role in Kremenets landsmen's activities.

Shafir was an outstanding speaker in three languages–Hebrew, Russian, and Yiddish. He wrote for various newspapers. In Russia he was a correspondent for the liberal paper Russian Glory. He published articles in the Kremenets newspaper Kremenitser Shtime. In Israel he published articles until the present on pedagogical subjects in Davar, Lemerchav, and Davar for Children.

[Page 46]

Yakov Shafir is beyond the “age of heroism,” and we wish him and his wife much nachas, health, and long life.

* * *

In Our New York Society–Our member William Kagan has assumed the post of society secretary. We wish him much success, and we hope that he, like his predecessor, Duvid Rapaport, will be active in distributing our notebooks among the members of the Society.

At our holiday table, the Society has wished the devoted secretary David Rapaport success in Israel.

* * *

Mrs. Helen Vaynberg from Kremenets and her husband Yakov saw the marriage of their son Aharon to Susan Fisher. The Society celebrated this occasion on January 10, and we wish them much luck. We hope that in time they will join us. Helen published poems full of longing for our old home. Some of her poems appeared in the Pinkas Kremenets in Israel and in the Kremenets yizkor book from Argentina.[1]

* * *

We have written about our generous mentor Avraham Barshap, who for many years was a kind of “minister of absorption” for immigrants from Kremenets in America. Recently Barshap has been ill, and we wish him a complete recovery so that he can continue his blessed work for many years.

* * *

Birthdays in common–Between Lag ba'Omer and Shavuot of 5731, the Rokhel siblings had birthdays: (a) Yosef Avidar Rokhel turned 65, (b) Moshe Rokhel turned 70, (c) Yitschak Rokhel turned 75, and (d) Sore Rokhel turned 80.

Their children held a common birthday celebration for all four in the home of Yitschak Rokhel's son, Eldad, in Moshav Beit Zayit near Jerusalem.

Invited were members of the wider Rokhel family, three generations, as well as distant family and near friends, about 100 people. The guests were treated to hearing about the family's ancestors–on the father's side, Rokhel–from the time of the Second Temple–and on the mother's, the Heylperin's, descended from King David's, all of it well documented…if you can believe that.

[Page 47]

And if not–so be it. One of the sons-in-law, Yakov Tsur, became jealous and undertook to show with signs and wonders that his family, too, Tsur-Tshernovits, came from King David. If he is right, we envy him.

At this opportunity, it is certain that all whose heritage is thus assured are princes of the house of David.

* * *

Purim in Haifa–As they do every year, Kremenetsers in Haifa tried to make a joyous Purim, and so this year they created the proper mood.

Members from Tel Aviv and elsewhere also participated. Also participating was a guest from Paris and his wife. This was Kremenetser Azriel Gorinshteyn. There were interesting costumes, particularly that of engineer Rayzman.

* * *

More Kremenetsers in Israel–Two families recently came to settle in Israel.

Shmuel Tsherepashnik and his wife, from Cordova, Argentina, after their daughter has already been in Israel for several years as a member of a kibbutz. Shmuel Tsherepashnik (his current name is Romanovitsh) lives in Herzeliyya and is retired. His new career is not clear yet.

The Kerler family: from Soviet Russia comes the Soviet writer Yosef Kerler, with his wife Heni, who is a Kremenetser, a Barshap daughter. Yosef Kerler participated in the journal Soviet Homeland and spent some years in Siberia. He was well received here and was welcomed by the head of state. They have already held a bar mitzvah for their son, and among their guests was Moshe Dayan, head of security.

With our whole hearts we wish these new arrivals a hearty welcome, success, and an easy transition to Israeli life and the life of Kremenetsers.

[Page 48]

A reception in the Levinzon Library in honor of beloved guests from abroad and to honor the 75th birthday of Yitschak Rokhel.

On Thursday evening, June 3, 1971, there was a celebratory gathering in honor of our beloved guests from Toronto, Canada, Fayvel and Tabe Barats; in honor of Duvid Rapaport from New York, who was not new to us; and in honor of Yitschak Rokhel's 75th birthday.

Manus Goldenberg, in a few words, described the many-faceted Barats family, welcomed Duvid Rapaport as a colleague, supporter, and encourager of the Kol Yotsei Kremenets booklets, and congratulated Yitschak Rokhel on his birthday.

Shike Golberg reminisced about the Barats family and its place in Kremenets, being beloved by both Jews and gentiles.

Fayvel Barats was grateful for this generous display.

Yitschak Rokhel–for the honor people shared with him.

Duvid Rapaport discussed the influence and unifying effects of Kol Yotsei Kremenets around the world.

He also read excerpts from his ballad “Kremenets” from the yizkor book published in Buenos Aires.

A piece by Mordekhay Katz, published in the Argentinian yizkor book[2], was also read. Everyone took great pleasure in hearing about “Chayim Pinchas the Water Carrier.”

People felt quite nostalgic. What happened later, sadly, readers can see in the notebook.

* * *

Guests from abroad–Lately a number of Kremenetsers from abroad have been visitors to Israel as tourists: (1) Azriel Gorinshteyn–Paris; (2) Anshel Zilberg–Winnipeg, Canada; (3) Hilda Shvartsapel-Royt and her husband–New York; (4) Fayvel Barats and his wife–Toronto, Canada; (5) Gershon Shkurnik and his wife–New York; (6) Yitschak and Genye Vakman; (7) the well-known cantor Karaulnik-Radzivilover, New York; (8) Avraham Barshap and his wife, Los Angeles.

They met with relatives, friends, and acquaintances. There was also a reception at the Levinzon Library for these dear guests.

As usual on such occasions, people recalled their memories of the past, sometimes with humor, read through chapters of our yizkor book, and enjoyed a warm and friendly atmosphere.

[Page 49]

Kremenets Poles write from London–London, 4/8/71–Honored Yehoshue Golberg!

“We received your letter of 1/15/71. Our answer has been delayed by the postal strike. We thank you for the two booklets from the “Kremenets Landsmen” and we are excited by your enthusiasm at the memory of Kremenets and your devoted work in producing the booklets. Unfortunately, we do not read Hebrew and so cannot fully enjoy the booklets. We thank you for the brief translation into Polish and ask that you send even further translations. Soon we will send you material from our collection for forthcoming booklets. We wish you the best and send hearty greetings to all Kremenetsers in Israel.”

Halina Tshernetska, Chair

Hermashevski, Secretary

Translation editor's notes:

- For translations of these yizkor books, see https://www.jewishgen.org/kremenets/kremenets.html and https://www.jewishgen.org/kremenets3/kremenets3.html, respectively. Return

- For a translation of this yizkor book, see https://www.jewishgen.org/kremenets3/kremenets3.html Return

Argentinian Division

Mordekhay Katz

Translation by Theodore Steinberg

A Meeting of Kremenetsers

On Sabbath evening, June 19, Kremenetsers gathered in the home of Chane and Chayim Fayer to mark the fourth anniversary of the historical victory of the Israel Defense Force in the Six-Day War, but the gathering spontaneously turned into a many-colored holiday. The presider, Chayim Mordish, began by recalling the fallen heroes of the Six-Day War. He also thanked the owners of the house for their generosity in putting it at our disposal and having decorated it for our celebration. Then he turned things over to our secretary, Mordekhay Katz. The secretary stated that the Fayers had dedicated the evening to the Kremenets Union in association with Chane Fayer's recovery from illness and also because their son Manolo and daughter-in-law Fufi had produced a new grandchild. He invited the ladies Bela Berenshteyn and Mrs. Shulik to take flowers to Chane and Fufi Fayer in thanks and appreciation. Because we could not celebrate Independence Day and the Six-Day War separately–since everyone could not be brought together twice in such a short span of time–every year we celebrate the two historical events together.

[Page 50]

The secretary invited 23 women to light 23 candles as a special way to honor the 23 years of the state of Israel. The candles were extinguished by the president of the cooperative Lo Esperanza, Chayim Mordish. The cooperative and all the women spontaneously and voluntarily contributed to the organization's treasury. Tsipe Katz took this opportunity to say a few words about the symbolism of the candles. The official word about the holiday's significance was briefly provided by the secretary Chayim Nudel. Later, while everyone amused themselves at the full table, Mordekhay Katz called attention to the fact that today the Jewish world was marking the 55th anniversary of the death of the immortal writer Sholem Aleichem. The Kremenets Union board then invited the secretary to read some Sholem Aleichem stories, which were received with great interest and pleasure. At the request of the attendees, Mordekhay Katz also read some of his writing from the Kremenets yizkor book in which he described people from Kremenets who served the community selflessly, really righteous people. But they never boasted. They just felt that they had to live that way. That was their ethical greatness. But they themselves never grasped this. (A righteous one, in his innocence, never grasps that he is a righteous one …) There was great applause. Finally, there was an interesting Israeli film about the Six-Day War and kibbutzim in the state of Israel. Late that night everyone left with elevated spirits.

[Page 51]

Congratulations

The board and the women's section of the Union of Kremenetsers in Buenos Aires sincerely wish President Chayim Mordish and his wife Shoshana good health after their escape from a traffic accident. We wish them health and active and necessary work for the benefit of the Union.

* * *

The board and the women's section congratulate members Chane and Chayim Fayer on the birth of their grandchild Sore-Tsirele. We wish them great pride, and to the parents Manolo and Fufi, we hope that they will raise her in a traditional spirit, in health and joy.

* * *

The board and the women's section congratulate members Freyda and Avraham Yergis on the bar mitzvah of their beloved grandson Mario (Meir). We hope that they will see him under the canopy, and to his parents Pakhata and Bernardo Vekhetilne, we hope that the bar mitzvah boy will grow to be a force in Israel for his people and his country.

* * *

We congratulate our dear brother and brother-in-law Shalom Mordish (in Israel) on his escape from a traffic accident. We wish him many healthy years in a peaceful country.–Chayim and Shoshana Mordish and children

* * *

The board and the women's section send hearty congratulations to members Nuta and Chayke Kiperman on the engagement of their youngest daughter Felisa to Carlitos Margolis and on the birth of a grandchild, Yosef Yakov. You should live to get much pride and joy.

* * *

The board of the Kremenets People's Union wish a full recovery to our important landsman, Pesach Ditun, so that he can continue his daily work.

* * *

* * *

[Page 52]

Sad News

We extend our deepest sympathy to member Yisrael Laybel and his sisters: Dobe (in North America), Ester, and Sore (in Israel), on the loss of their dear brother Hershel, peace be upon him (in North America). May you find comfort in his heritage and know no more sorrow.–Union Board and Women's Section

* * *

We extend our deepest sympathy to our landsmen Tuye and Tsipe Shnayder on the loss of their dear brother and brother-in-law, Velvel Shnayder. May you be free of sorrow!–Committee of the Kremenets Union

* * *

The board extends our deepest sympathy to our landsmen Dokha and Meir Vaytsman on the loss of their sister, Chane Vaytsman. May you be free of sorrow!

* * *

As we close this issue, our friend Vakman has brought us the sorrowful news that our dear Binyamin Barshap, of blessed memory, has passed away. We send our condolences to the family in New York. Be consoled by the good name he left behind.–Organization of Kremenets Emigrants in Israel

[Page 53]

Contributions from Abroad

Shmuel Taytelman

Translation by Theodore Steinberg

As we do in each issue, we present a list of contributions from abroad from individuals and from landsmanshaften.

| For the benefit of Kol Yotsei Kremenets |

| 1/15/71 |

New York Landsmanshaft via D. Rapaport |

$ 10 |

|

| 03/01/1971 |

Hebrew Union College, Cincinnati |

6 |

|

| 3/28/71 |

Yosef Margalit, Winnipeg, Canada |

25 |

|

| 4/25/71 |

Argentine Landsmanshaft, via Mordekhay Katz |

120 |

|

| 4/28/71 |

Morris Medler, Arizona |

20 |

|

| 5/20/71 |

New York Landsmanshaft |

30 |

|

| 6/27/71 |

Binyamin Barshap, of blessed memory, New York |

250 |

|

| |

|

|

$ 461 |

| For necessities |

| 3/20/71 |

Yitschak Vakman, New York |

$ 50 |

|

| 04/08/1971 |

Yitschak Vakman, New York |

100 |

|

| 6/29/71 |

Yitschak Vakman, New York |

100 |

|

| 6/29/71 |

Binyamin Barshap, of blessed memory, New York |

250 |

|

| |

|

|

$ 500 |

| For the Levinzon Library and other organizational responsibilities |

| 04/08/1971 |

Norman Deser (NY), Newtonville, Mass. |

$ 50 |

|

| 4/26/71 |

Hilda Shvartsapel, New York |

100 |

|

| 06/04/1971 |

Fayvel Barats, Toronto, Canada |

100 |

|

| 06/04/1971 |

Max Shapinka, Toronto, Canada |

100 |

|

| |

|

|

$ 350 |

| |

Total |

|

$1311 |

| In Israeli currency |

|

|

|

| 3/71 |

Azriel Gorinshteyn, Paris |

50 lirot |

|

| 04/06/1971 |

Duvid Rapaport, New York |

50 lirot |

|

| |

|

|

100 lirot |

Sincere gratitude to our friends and donors.

Error processing SSI file

Error processing SSI file

Kremenets, Ukraine

Error processing SSI file

This web page created by Jason Hallgarten

Error processing SSI file

Updated 23 Dec 2022 by JH