|

|

[Page 1]

|

[Page 3]

Translated by Eugene Sucov

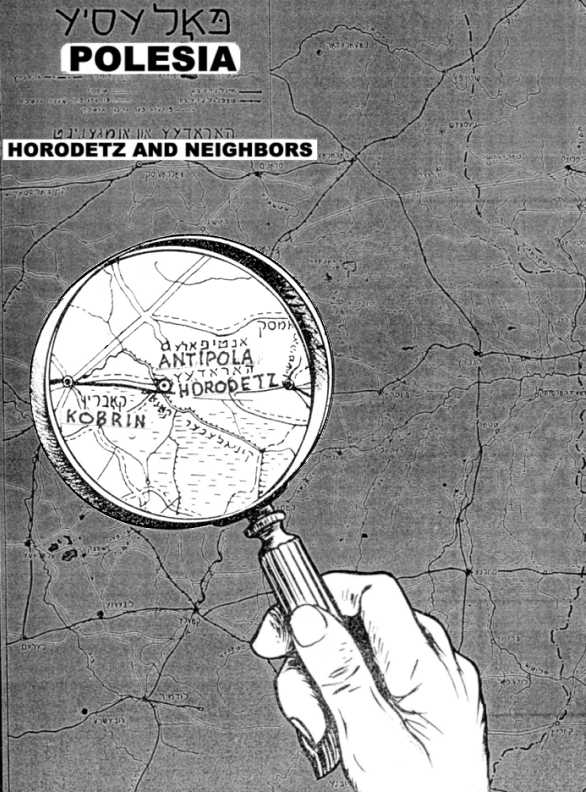

From contemporary drawings we can see how Horodetz appeared in those years when the entire area from Pinsk to Kobrin was overgrown with a thick forest and settlements were very few. In 1559 a forest path was hacked out from Pinsk, cutting through Tarakan and Horodetz, to Kobrin and Pruzhana.[3] In those times Horodetz did not yet have a river. Where now is a beautiful meadow, there were swamps through which the river Mokhavetz cut its way from Pinsk to Kobrin. Horordetz was then like an oasis in a desert; a settlement surrounded by forests and swamps in which roamed various wild animals.

The details of life in ancient Horodetz are not known. According to Babrovski, the historian of the Grodno gubernia, Horodetz contained, at the end of the 16th century, 5 streets: Kobrin, Freishibadske, Pinsk, Groshevski and Ilinske. In addition, there was a business market since there were 222 dwelling places, 15 taverns, 11 of which were beer parlors, and 23 breweries. In older official documents Horodetz was described as a town and not as a village.

It is worth while to examine more deeply the legend, which old Horodetz Jews and also residents of the nearby village of Antipolya (7 km from Horodetz), used to relate, namely, that in former years Antipolya and Horodetz were one town.

Ask yourself:

It is worthwhile to remark on a major error, by now already printed in the Yiddish-English encyclopedia. There it says, “The small village of Horodetz was at one time a part of Kobrin, but it was destroyed in 1653, when it was overrun by the Swedish army.”[6] This error is traced to a faulty translation from Babrovski's history book. He stated there that Horodetz was administratively and economically connected to Kobrin but that didn't mean they were one town.[7]

It is clear that Horodetz was, in those days, a central distribution point and people settled there to take advantage of the commercial activity. In summary, from the 17th century onwards, the Horodetz Jews were quite well integrated, according to the concepts of that time. This can be seen according to the accounting of the head tax which Horodetz Jews paid in 1673. They gave 51 zlotas. This was not a small amount in that time.[10]

Also, from another source, we learn about the Horodetz Jewish community and the role it played in Jewish life. This can be seen from regulations promulgated by “The Council of Four Lands”[11] in 1623. One of those decisions allocated a sum of money to Horodetz in order to renovate their synagogoue.[12] Horodetz is also included in the list of towns for which The Council of Four Lands worked out special regulations concerning wandering soldiers.[13]

According to various other documents, the Horodetz Jews joined with Brisk which was itself a part of the “Council of the Lithuanian Nation”, which was composed of Brisk, Grodno and Pinsk.

It is worthwhile noting that the Jewish Chronicle, in writing about Bogdan Khmielnitzki's revolt in 1648, never mentioned Horodetz. However it does mention that in Kobrin, 200 Jews were murdered.[14] Is it likely, that if Horodetz was part of Kobrin, it would have escaped the massacre?

How did the contemporary Horodetz Jews live? How large was the contemporary Jewish community?

For these 2 questions we can get a partial answer from an old Polish document. From this document we can learn that the Horodetz community grew in numbers and in power. This document itself is not encouraging. It is a document which illustrates the helplessness of the Jews and their tragic condition even in the land where they had, as it were, national autonomy.

The Jew always lived in terror and all through those times he was exposed to the danger of expulsion and the confiscation of his property. How did the Jews survive the terrors at the end of the 17th century? Exactly what brought on the dark and evil decrees is not known. What we do know we learn from an old Polish document, a report of a legal ruling concerning Horodetz Jews, dated July 10, 1700.[15]

It deals with a Polish woman who had loaned money to several Horodetz Jews. On which terms they borrowed the money was not mentioned. All that we can be certain of is that they did not pay off the debt. The Polish judge in Horodetz ruled against the Jews. The decree was that the entire community must suffer. All Jewish property must be confiscated, even that which was outside the boundaries of Horodetz. And all the Jews, young and old, were expelled from Horodetz.

Was, indeed, the decree carried out according to the letter of the law or was it made less harsh? This is not known. But this is certain, that the protocol of the decree was saturated with hate for the Jews. The phrase, “The Untrustworthy Jews” was repeated in the protocol many times.

From the same document we can infer that Horodetz was then a town, since that is how it was described. Also the names of the 12 Jewish representatives can be confirmed. One of them is Missan (Nissan?) Haranovitz. It is worthwhile to ponder these strange names since it was not a small community. Concerning subsequent years there is very little knowledge. In 1766, we know, there were 254 Jews in Horodetz, a quite sizeable community for those years.[16] It appeared that the newly excavated canal, through which Horodetz became rejuvenated [17] also had an effect on the Jewish population. The population was nearly doubled; in 1847 there were in Horodetz 422 Jewish souls.[18] Unfortunately the Horodetz Jewish community did not hold on to its increase. We learn from a royal statistic of 1860 that in Horodetz were 295 Jews among 700 non-Jews.[19] Later, in 1878, again the community grew and in Horodetz were 567 Jews among 1264 residents.[20] And in 1897, the Jewish population numbered 648 among 1761 non-Jews.[21]

In 1793 Horodetz was transferred to Russia and incorporated into White Russia (Belarus). From that time on a new chapter was started in the story of Horodetz. This chapter continued until 1914 when the first world war broke out and the Romanov dynasty no longer had any influence over Horodetz.

It is unlikely that the Napoleonic war (1812) had no effect on the Jews of Horodetz. All we know is that there were Jews siding with the French and others who were on the Russian side.

But we do have exact information about the Polish “povstanya” (rebellion), especially the second “povstanya” in 1863. Many Horodetz Jews sided with Poland. They provided the Poles with food and also with hiding places. But, when the Jew hides the Pole, is the chicken in the middle of the roosters, and the Pole does not forget to shout at his Jewish saviors, “Zshid Parkati, Zdeim Tshapki” ( Filthy Jew, take off your hat).

The Russian regime settled scores with the Jewish “saviors” and one of the sacrifices was Devorah, the sister of Hersh Leib Sirata from Vigada, who was, for this sin, exiled to Siberia.

The suppression of the Polish revolt also overturned the political situation in Horodetz. Horodetz, with the surrounding villages, such as Rodetz, Vorotepolyeh, Tshelishtshevitsh, Ferekhreshtsh and others, had belonged to the Polish landlord, Voret. The Russian regime confiscated the property of the Jews and sold it for a small sum to the old man, Shter, who bought it from the Romanovs. The Horodetz Jews paid “platzveh” (land tax) to Shter and afterwards to his younger son, to whom Horodetz, Vorotepolyeh and Palayeh belonged.

Under the Tsar's regime the Horodetz Jews suffered all the evils and persecutions which the government dreamed up for Jews. Also the wave of pogroms which had raged in Russia for the past 80 years once again engulfed Horodetz Jews. In the beginning of the 80 years the Polesia railroad line was built from Zshavinke, near Pinsk, through Horodetz. The Russian regime brought Russians from the heart of Russia to build this raliroad line. In Horodetz were stationed some of these Russians who were working on the line. The air, which the Tsarist regime had poisoned, was full of hate against the Jews. The Russian ruffians had only to wait for an opportunity and they would beat the Jews.

This is how it was. One time, during the night, on the 20th of July 1882, the ruffians got drunk and began breaking windows, beating Jews and ravaging the Jewish community. It was a miracle that the Christians did not join them. The Uriadnik (Police captain), Shabnov, along with the Starshina (town elders), did not allow the pogrom to get any worse. Also the young Horodetz Jews were not sitting with folded hands and they fought back.[23]

A second time, in the summer of 1906, when the Russian ruffians rebuilt the iron bridge, another pogrom descended on the heads of the Jews, and we were overcome with terror.

This canal was opened with a great parade in the year 1784. In the great crowd was also the Polish king, Stanislav August Poniatavski, who made a special visit to Horodetz in order to personally witness the event.[24] The accomplishment was very great, and much was spoken and written about this at that time.

The canal, which ended here in Horodetz until 1841[25], joined the river Moklhavetz, near Kobrin, in the middle of the river Pina from Pinsk. In other words, this canal connected the 2 great rivers, Dnieper and Bug (consequently it was called the Dnieper-Bug canal). Thanks to this canal the Black Sea was connected to the Baltic Sea. The length of the canal was over 75 km.

Because of this canal one could ship through Kobrin, Brisk, Warsaw and Danzig various products such as grain, whisky, barley, hogs, candles, cloth, human hair, hog hair, tar, timber and ceramics.[26] Thanks to this traffic, Horodetz was called “Little Danzig”, since Horodetz was transformed into a place for export and import business.

We read the following statistics for 1860: 23 ships and 69 barges were downloaded, carrying 29,315 “poods” (1 pood = 40 lb.), with a value of 104,438 rubles. And, in the same year, were loaded for export 32 ships and 9 barges carrying 28,393 poods worth 121,954 rubles.[27]

Above the canal was a primitive bridge which used to be opened with a rope when a “Berlinner” ( wooden boat) or a “Parakhod” (steam ship) needed to pass through.. About 30-40 men used to pull the rope until the bridge opened. The crowds of travellers used to have to wait a few hours until the bridge got itself together before they could cross over. In 1883 a wooden bridge was made high enough that even a Parakhod could pass under it.

Horodetz became an important center because of its canal, and the Russian regime made Horodetz also a military stonghold. From about 1876, soldiers began to be stationed in Horodetz. In the beginning there was just one company of soldiers (about 100 men), but thereafter a total of 4 companies were stationed in Horodetz. The soldiers left Horodetz in 1888 but 5 years later they returned to stay until 1896.

With the outbreak of the first World War, the Horodetz canal lost its usefulness. We stopped exporting timber to Germany and the canal no longer carried commercial shipping; it became a simple local stream.

Commercial importance returned to Horodetz when the Polesia railway line was constructed (1882-1884). The line, which went behind the town, also required an iron bridge over the canal, so a train station to meet the canal was built a few minutes from Horodetz. Because of the importance of the canal, the local train station was called Dnieper-Bugskaya. Years later, under Polish rule, local citizens requested that the name of the station be made the same as the name of the village, Horodetz.

The canal and the railroad connected Horodetz with the outside world, and merchants with various businesses would come to Horodtz because of its markets. Along with the building of the train station, Horodetz also became the location for a central post office, from which was sent mail to Antipolya and other nearby villages.

Horodetz was much beautified when the highway between Horodetz and Antipolya was built (1908-1910). The main streets of the village were paved and mud was cleared away.

By 1928 Horodetz was linked to the outside world by telephone. The single telephone was in the post office from which we could connect to other towns.

During this time the highway between Kobrin and Antipolya was built (21 km) and an autobus route was established between Kobrin and Antipolya, passing thrugh Horodetz.[28] This traffic strongly connected Horodetz to her nearby towns and villages.

Occasionally the Rav (teacher) would study with several young men who were ready for advanced learning and preparing to be “Poskim” (experts in a branch of Talmud) and judges.

The Jewish children taught themselves Russian. Very few Jewish children attended the “Schola” (Russian folk school), which had only one teacher for over 100 gentile children. In addition, the sanitary conditions were not fit for the Jewish child.

When the enlightenment came to Horodetz, the young men of the synagogue would read “forbidden and false” books hidden under the Gemara. Some of these young men, who were corrupted by these stolen waters, never returned. They lost their father and mother and lost themselves in the outside world seeking “education”. However, some were able to resist the pull of enlightenment. Only those with strong character stayed behind in the town, where they were able to satisfy their thirst for education and become famous personalities. One of these is the famous and learned Dr. Israel Michael Rabinovitz [29] who, himself, did not return to Horodetz. However, his nephew, Leyb (Reb Joshua Jacob's son), who had “gotten lost” with him, did return to Horodetz.

When Khassidism began to spread over the Jewish settlements, it also did not overlook Horodetz. Horodetz became a khassidic fortress of the Karlinner dynasty. Karlin, which is not far from Horodetz, in a short time found open hearts for the Karlinner doctrine. Many years later, when Reb Moshe from Kobrin began to spread his khassidic teachings, Horodetz Jews began to travel to Kobrin to be near Reb Moshe. After his death, they became his followers.

We cannot say that the khassidic way came in to Horodetz without wars and arguments. The opponents of khassidism were not quiet, but the sharpness of the arguments was moderate and did not inflame itself, as it did in other towns and villages.

Another movement which fought fiercely to take root in Horodetz, was the Zionist movement. In the beginning, when Dr. Herzl emerged onto the Jewish arena, there were already several Jews in Horodetz who were inflamed by the idea of independence. Little by little this idea captured the entire Jewish community. Thanks to the Land of Israel movement, several Jewish families were saved from the murderous hand and they lived in and helped build the Jewish State.

The new rulers little by little began to introduce the German language into the folk school. Horodetz Jews, young and old, began to teach themselves German and learned how to get along with the German “Order”. When the Germans lost the village, Horodetz became without civil government and various gangs terrorized her by day and by night. Finally Horodetz was included in the new Polish state. Then the terror became “legalized”. The Polish regime quickly put the robbers and murderers under her protection.

It didn't take long before Horodetz was once again destroyed in the war between the Russians and the Poles. We prepared to escape but already there was no place to go. There was no longer the possibility of leaving and the Jews no longer had the strength to leave. The few Jews who still remained in Horodetz were the old and the children. The younger Jews had immediately gone to peaceful Brisk and began to escape to America.

Finally peace was secured and Horodetz became a part of Poland. The Polish regime introduced harsh laws about racial purity against those Jews who were not residents. The truth is, they were evil decrees specifically aimed against the Jews. The Polish regime also pased a law of compulsory public education for every child. Jewish children had to attend the “pavshekhne” (Polish folk school) till noon and only after this could they quench their thirst for Jewish studies.

The Polish government also introduced military service. The Horodetz Jews were not at all enthusiastic about this. But, many young men did their duty and went into the army. Some of them even excelled. But what does one do when one comes home after army service? What trade can be followed when the Polish regime has closed off all the ways in which a Jew could make a living?

The spirit starts to think about emigrating. But where should one go since all doors are closed? Two streams of immigration pulled them. One towrds Eretz Israel and the second to South America to countries like Argentina, Brazil, Cuba, etc. Horodetz gradually was emptied of its Jews and the Jewish pulse slowly weakened.

This was the situation until the outbreak of the second world war in 1939 when Horodetz was occupied by the Red army. Now, the Soviet regime began to rule the village. Subversive ideas came in on the backs of writers, whose books the Russian soldiers brought in, who promised “complete redemption” not only spiritual but also physical. The Russian army doctors were not burdened with soldiers so they lived very well in our town. But they spread rumors that the Soviet regime had exiled several Horodetzers and that a Horodetz girl had to poison herself.

After a short time Horodetz was captured by the Germans and Horodetz was wrapped in the embrace of the Nazis. Horodetz Jews were enslaved, tortured, killed and confined to a ghetto. The Horodetz Jews did not surrender but rather rebelled, sabotaged and escaped to the partisans in the forests, who were giving the Germans plenty of trouble.

But Hitler was stronger. He controlled everything and everyone. He smashed the houses to the ground and erased the memory of the cemetery. The grave stones were taken and used as paving blocks for the streets.

Horodetz became empty of her Jews. No more was there Jewish charm in the old Jewish village, no longer is heard the voices of children, Jewish hearts no longer beat there. A quiet cemetery atmosphere is felt in the air, which is soaked with blood. No traveller can stay there because of the sadness which hangs in the air. Even the extra-ordinary surviving Jew, David Volinietz, cannot stay there for more than 2 days. Every step reminds him of a martyr, every stride is bound up with memories of the happy past, which is no longer there.[30]

Horodetz once again became Russian in 1943. Did she also become Jewish? Do Jews live there? Does a Jewish life exist there?

As far as we know, no Jews live there now. It was a Jewish village and now it is no more. May her name be written in the history of Jewish martyrdom with golden letters!

|

|

| Aharon Itche Leyzer's house (about 200 years old) [since 1949 another 60 years have passed…] This was drawn by Israel Zusman |

References and Translator's notes

Ida Selevan Schwarcz and Roman Turovsky, who helped me understand obscure Yiddish / Russian expressions.

Translator's note: In the original Yiddish, the rhyme scheme for each 4 line verse was a-b-a-b. I have not tried to replicate that rhyming scheme in the English translation.

Once there was a shtetl small,

Horodetz was it known as.

And what happened to it

Is a secret known to one and all.Not a word in history is written

About its people, secular or observant.

And from the houses and crooked alleys,

Only a trace is remaining.Now I remember how I went to kheder,

Where summer and winter it was my home,

And where “Old Man Sender” constantly taught

Aleph bais with a whip.In the cold winter nights

We would go together from kheder

Wrapped in an overcoat

With a lantern in our hands.

[Page 11]

I was taught by many teachers

In rooms with many children.

But inscribed in my memory

Is the melody of Shimon Isaacs when he chanted from the Bible.Comes the snow and the frost

And everything immediately is frozen,

Birds stay in their nest

And kids slide on the frozen river.Who doesn't think abut the cold shul

With a matza on the wall

To expel the old ghosts

With an invisible hand.The study hall in its street,

And the small Hassidic shul in the market.

We used to become angry over an aliyah wrongly given

But we would still enjoy the service.Where are you now, anti-hassidim and hassidim?

Jewish scholars and story tellers,

Jews working and toiling,

Jews ordinary and Jews remarkable?Where is R. Itzik's guest house

Where every weary traveler

Would find a home

So he could rest his legs?Where is the Rav R. Khayim's beautiful presence,

With his good attributes in his modest life?

R. Aryeh's ripe fruit became old,

His soul was freed from troubles and suffering.

[Page 12]

Where are Khayim Nissan and Naftali, the doctor,

Asher David, the ritual slaughterer as well as blacksmith,

And Shimon Isaacs roaring a sad song,

And the fire brigade putting out a fire?Where are the young pioneer kids

With courage in their hearts and plows in their hands

Who had all prepared so rapidly

To travel and recover our land?Where are the tailors, shoemakers and wagon drivers?

Where is Big Moshe in Karlinski's store?

No longer in Horodetz are there any Jewish shops,

All wiped clean from a black street.And do you remember Fridays in the summer?

The Horodetz river would call us

And Jewish women and men joyfully bathed

In honor of Shabbat.On the river's small waves

Occasionally would swim from Pinsk

A steamer and also row boats

With important merchants, as many as from Minsk.Quiet would life flow there,

Quiet as the waters in the river.

Each one would to somethng aspire,

Whether children or whether wealth.

[Page 13]

Did Satan not envy

Our peaceful life and streets?

Did he not spin and contrive

A partnership with the Angel of Death?The Bund was banned and locked up,

And immediately Horodetz overflowed with troubles.

From ten measures of grief and anguish

She drank in total, nine.Said Satan to the Angel of Death,

“In serious Poland have some fun.

Go down there and take a whip

And give them there a life which is called Germany.”“With this whip break every limb

Of this difficult people, the Jew.

And whoever is weak and is wailing

Ever more strongly shall you strike him.”Every Jew went to their slaughter

With mute hearts, depressed and grieving.

In the evening sinks the sun,

Red faced and ashamed.In a mood like that of Yom Kippur

From their depths emerged a prayer,

“Ah, God of Abraham and Sarah.

Why, from all the sinners in all the worlds,

Did you select us to be a sin offering?”

[Page 14]

We forget the heavens, the sun and earth.

We will forge a sword,

A sword of hate, iron and steel,

Like the Maccabis did long ago.We will “Destroy the memory of Amalek from under the heavens”

And then we will drink a l'khayim to us all.Once there was a shtetl small,

Horodetz it was known as.

And what happened to it

Is a secret which everyone knows.

Final comment by the poet:

Among the grievers sorrowful and stooped

As a mourner during the 30 days of mourning,

Stand I, with tear filled eyes,

And recite the Kaddish for the Holy Ones who were murdered.

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Haradzets, Belarus

Haradzets, Belarus

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 16 Oct 2010 by LA