|

|

|

[Page 137]

Translated by Jerrold Landau

[Page 138]

[Page 139]

by Sh. Papish

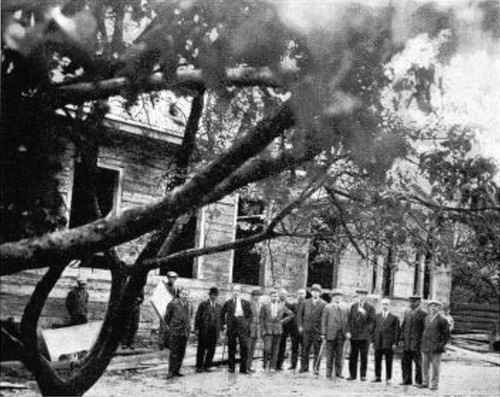

The educational and cultural enterprises in the town were organized by the Zionist organization. They also took responsibility for its budget. The school buildings stood on a public lot next to a grove of trees. A new building was erected over and above the two old buildings that were fixed up and rendered appropriate for their purpose. The eight classes and the kindergarten were housed in spacious rooms, full of light and fresh air. We can attribute an honorable place in organizing the educational institutions in our town and ensuring their ongoing success to Reuven Mishalov, who served as the first principal of the school. His organizational talent, energy, and influence on both the communities of parents and children, his dedication and talents in forging proper relationships also with other factors, even taking a strong stance at the time of need, along with the assistance of active members of the Zionist organization and some of the teachers, were all factors that helped overcome the many obstacles, and ensured the development of our educational institution to a high organizational level, and even to an educational level fitting for its name, already during the first years of its existence.

|

|

[Page 140]

The second stage of the development of our school and raising it to an educational-pedagogical level that brought it fame as one of the finer schools of Poland came with the change of guard, the growth of the teaching staff and the hiring of young teachers who were graduates of Hebrew high schools and of the Hebrew seminary in Vilna. This was under the leadership of Avraham Olshansky. This was the era of splendor of our school, which was the pride and glory of the Hebrew community of our town.

Hundreds of students were educated in the school. The classes were always filled to the brim. Children from the settlements of the region, from the nearby village of Choromsk to the village of Chrapun on the border of Soviet Russia, a distance of fifty kilometers from the town, would come to continue their studies in the upper grades.

The leadership of the school, most of the members of which were members of the Zionist organization, already they actualized to a significant degree the principles of the law of compulsory education. Tuition fees were graduated. Those of meager means, whose numbers were not small, paid from 25% to 50% of the regular tuition fees. Many parents who were unable to pay were completely exempted from tuition fees.

Many of the graduates of our school continued their studies in the Tarbut Gymnasium in Pinsk, in the Hebrew Teachers Seminary in Vilna, or in other upper-level and professional schools.

Throughout the years, a club for knowledge of the Land functioned in the school under the direction of Chaim Branchuk of blessed memory, one of the dedicated teachers, who served as the secretary of the Zionist organization for many years. His entire life was dedicated to educating the young generation and the building up of the Land. His desire to make aliya to the Land was strong, but he did not merit such. He oversaw with dedication the aliya of many of his friends. With the conquest of Poland, he was exiled along with the members Yaakov Yudovitz and Dov Rimar, members of the final Zionist council, and died on route to far-off Siberia.

Classes in Talmud for the students of the upper grades took place in the school for many years. The teacher was Rabbi Shneur Zalman Shapira of blessed memory. He would explain his lessons in Hebrew. The late rabbi was the chairman of the Mizrachi organization, a dedicated Zionist who participated in activities for the benefit of the funds and in other Zionist activities.

In 1933, the Bnei Yehuda [Sons of Judah] organization and Bnei Yehuda Cubs were founded alongside the school. This was the youngest Zionist organization in our town, and in the Zionist movement in general. Its members were the children of the first grade: the children of the kindergarten as well as four-year-olds who were still pre-kindergarten. Members of the Hebrew organization for young children kept faith with the Hebrew language. They refused to speak Yiddish. There is a story that one of the mothers urged her four-year-old daughter to speak to her grandmother in Yiddish, for the grandmother did not know Hebrew. The child responded, “Mother, how can I speak Yiddish? I have taken an oath to speak only Hebrew.” Even the shopkeepers, including those of the candy stores whose owners were gentiles, became comfortable with the Hebrew language, out of fear of losing their young customers.

During that period, Hebrew on the Jewish street in our town was not only the daily language for hundreds of youths and children, but also in every house where the children lived.

At the end of the summer of 1935, when Yosef Baratz of Degania returned to Warsaw by train after visiting our town, he told those travelling with him about his impressions of his visit, with enthusiasm and appreciation. He described the wide-branched Zionist activity, discussed the achievements of the school, and especially of the Bnei Yehuda Cubs and the living Hebrew languages that had taken root in one of the towns of the remote district of Polesye. He told about Pablo, the guard of the school, and the maid in the home of the school principal, who both spoke Hebrew.

Our school was a ray of light in the gray, day-to-day life of the Jewish community of the town. Every celebration in the school – the Lag B'Omer parade, the year beginning, the distribution of report cards – turned into a holiday for the entire Jewish community. The streets filled with people, and the faces of the Jews beamed with joy and national pride at the site of hundreds of school children walking all together along the streets of the city.

The celebration of a decade of the existence of the school was an unforgettable event. The beautiful ceremony was prepared with exactitude and precision, and was carried out with success. The magnitude of content turned the celebration into a national festival for all the Jews of the town. Dr.

[Page 141]

Zweigel, the principal of the Hebrew seminary in Vilna, participated in the celebration on behalf of the Tarbut headquarters in Warsaw. On his way from the railway station, he passed through the streets of the city in a fine wagon hitched to beautiful horses, as the schoolchildren holding flags and the Jewish community greeted him with joy. The impression was strong. This was a very impressive demonstration of Hebrew education in one of the veteran communities of the towns of Polesye. These were moments of full satisfaction for the Zionist movement in the town. The gentiles whispered that the Jewish minister had come to visit the school of the Jews.

|

|

The Zionist library and the Zionist hall, which was opened in the latter years with brief interruptions, served as meeting places for the members to organize mutual activities. The active female members during that period included Nechama Friedman, Batya Shtofer, Shoshana Gloiberman, Musia Geier may G-d avenge her blood, Sonia Baruchin may G-d avenge her blood, Chaya Geier may G-d avenge her blood, and others.

During festivals, a “Zionist minyan” was held in the school. It always had many participants, even some who did not regularly attend synagogue. For that as well, we did not require any outside help. The entire “staff” was from amongst our members. Yerachmiel Rimar and Shmaryahu Reznik, may G-d avenge his blood, served as the prayer leaders. Moshe Erlich served as the Torah reader. Berl Katz would bless us with the Priestly Blessing. We also had a group of Levites[1]. The Zionist minyan imbued the members with a unique festive spirit.

Translator's footnote

by P. Dobrushin

The days of my childhood in our town pass before my imagination as if in a dream. The nicest memories are from the school. At first, we learned in the cheder with the melamed Shimon Leichtman. The cheder was large and spacious. Tens of students were hunched over the long tables, repeating enthusiastically: Kometz aleph oh[1]. The teacher walked among us, ensuring

[Page 142]

that the letters of the Holy Tongue would be absorbed well in our young minds. He derived pleasure from a diligent student who would go to the blackboard and recite his section properly. He did not spare threats from an indifferent or lazy student.

We got older, and transferred to the cheder of Reb Yosef Begun. There, we learned arithmetic and Chumash, and Rashi's commentary was not strange to us. We were already scholars to no small degree… Others of our age studied with Reb Shweidel. We were diligently engaged in our studies almost without a break during all hours of the day. We came home at night by the light of a lantern. This was over the course of many months.

One day, the appearance of the cheder changed. News of the opening of a school spread on the street and at home. This became the topic of conversation of the day. What was this all about? None of us children knew. Our parents toiled to establish that institution, and the future principal visited the cheder to inform us of the impending change. We were to become the third grade, the highest grade in the school when it was to open.

I recall how Father of blessed memory discussed the school with others. He had many meetings with his committee, until that splendid institution, in which we first and many after us were educated to love the nation and the Land, became firmly based. What feelings pervaded on the street when the benches were carried to the school building on the shoulders of the parents. I will never forget the first day of classes. At first, we studied in the old building, which seemed to us like a palace at that time. New worlds were revealed to us, and they were especially attractive and interesting. It was good to exchange the cheder for the Tarbut School.

The school flourished from year to year, and its students were successful in their studies. Teachers came from outside the city. A kindergarten was opened. At first, the kindergarten was looked upon with distrust by the parents. However, it quickly gained admirers. We became a modern city of culture, bustling with “scholars” of school age. Our teachers suffered from a delay in salary more than once. Our parents lovingly signed the contracts that were given to the teachers as an advance.

The students of the school quickly turned into warriors for the Hebrew language. A brigade of Hebrew speakers was formed, which spread through the outskirts of the city and its shops. They stubbornly spoke Hebrew, and “forced” the adults to answer them in that language.

Years passed, and grade three became grade seven – the first graduating cohort, “the most important students.” The founders, builders, teachers, and workers on behalf of the school merited to celebrate with joy the graduation of the first cohort, to which I had the pleasure of being part of.

|

|

[Page 143]

The parents, teachers, and many guests gathered in the yard, and the ceremony of distribution of diplomas turned into a festival for the city. We graduates had a multiple dose of joy. Our exam period had ended. These were literal matriculation exams, which took place in the hall of the firefighters, and they left a great impression upon us with their seriousness. Now, we were happy that we had gotten through them.

The teachers and the parents' committee sat next to a decorated table. With holy awe, we approached one by one to receive our diplomas from our dear school. At this sight, tears flowed from the eyes of many who knew us well. The people of our city were used to seeing us going out on excursions with the song of Chazak Veematz [Be Strong and of Good Strength] on our lips. On occasions, we provided them with pleasure as excellent actors in the performance of Shnei Nigunim Li [I Have Two Tunes] by Y.L. Peretz. We also astonished them by exercising before their eyes, and we visited their homes on occasions for matters of the Jewish National Fund.

The community was proud of us, and participated in our joyous occasion with a full heart. It is unfortunate that they did not merit to see us among the builders of the State, actualizers of their great dream.

Translator's footnote

(from the Pinsker Shtime [the newspaper Voice of Pinsk], 1934)

by Litman Gotlieb

The years of existence of the Hebrew school were difficult. It had to fight with the Orthodox from one side, and with the Yiddishists from the other side. It had as many internal opponents as it had external opponents.

In addition, it also had to struggle with the indifferences of the parents and the enticement to send the children to other schools.

Today, the school has 400 students. All the students, from the second grade to the seventh grade, speak Hebrew amongst themselves at home and on the street. When they enter a store, they speak to the shopkeeper in Hebrew. He speaks Yiddish and they respond in Hebrew.

A wall newspaper is put out by the students (with the help of the teacher) every week. Student clubs for literature, history, and the like are organized. There was a carpentry shop for the students of the upper grades. Graduates of the institution also worked there. There was also a sewing course for the female students and graduates.

To this day, the school has graduated five cohorts (more than 100 individuals). A large portion of them continue their studies in Tarbut institutions such as the gymnasium, seminary, technion (of Vilna), and trade schools. A portion have made aliya to the Land of Israel, and a portion work in kibbutzim.

All the graduates of the school are organized into a special club under the guidance of the principal of the institution, Mr. Olshansky. Constant contact is maintained between the club and the graduates who left David-Horodok.

Now, they will be celebrating the decade of the existence of the school, with the participation of the teachers of the institution, its graduates, and its students. An exhibition is being prepared (through the efforts of the supporters and the students), and a celebratory newspaper will be issued.

However, the great depression with the accompanying impoverishment has brought difficulties to the institution. Nevertheless, we can hope that all those who bear the burden of the school to this day will continue with their work into the future – work that is difficult, but blessed and with significant results.

by Moshe Meiri (Moravchik)

The Hebrew school in the town was renown throughout all of Poland. That school educated an entire generation in the spirit of Hebrew culture and the ideas of national revival.

[Page 144]

How pleasant it was to see hundreds of boys and girls hurrying and running to school every morning, with their schoolbags on their shoulders and joy rising from their mouths.

The school that stood in the large yard on a side street was a first-degree cultural center of this town.

The school and its large yard served as a meeting place for boys and girls not only during school hours, but also in the afternoon. They spent many hours in the yard playing or participating in games.

This splendid school, with hundreds of male and female students, was the largest enterprise in the city from old times until the destruction.

The teaching staff, who were carefully chosen, did not just see their role in teaching. They also saw themselves as bearing a loftier task – the education of the younger generation to a new life, and raising them as faithful children to the Hebrew nation, and guiding them along the path that leads to Zion.

Indeed, very many of the students of the school followed that path in which they were educated. Very many of them recall that study hall with great appreciation, awe, and honor. To this day, it remains as one of the finer memories of the life that has passed and the reality that is no more.

by Yaakov Hochman

Abrasha Olshansky, the principle of the populist Tarbut School in David-Horodok, had a strong desire for his students to speak Hebrew in their day-to-day lives, rather than only at school. The objective that he preached day and night was not simple, and he found many ways to influence the people of David-Horodok. For example, the Hebrew teacher promised celebratorily that any student who would speak Hebrew outside the walls of the school would get a boost in marks – that means, a student who was fitting for a “satisfactory” mark would get “good,” and a student who was fitting for “good” would get “very good.” However, all the enticements, requests, and speeches did not help: not because of the refusal of the students, but rather because of the environment in which they lived. Meetings and activities in Hebrew were held at the youth movements of Hashomer Hatzair [Young Watchmen], Hashomer Haleumi [National Watchmen], Beitar, etc. However, at home, at the grocery store, and in every place where one had to meet with adults and not just youth – this was virtually impossible. How could one approach Mother and speak to her about food, clothing, etc.? It would be as if you were speaking to her in Chinese. It was somewhat easier with the men, for some of them understood but did not speak, and others spoke a bit. There were a few who were fluent in Hebrew, and one could “get along” with the help of the hands and feet [i.e., gestures]. The objective was more difficult with the women.

Thus, it was both ridiculous and interesting to see Meir Plotnitzky, a twelve- or thirteen-year-old student, decide suddenly – I believe this was at the end of the major vacation of 1934 – to speak Hebrew with every Jew, whether or not they understand. Meir was stubborn and strong-willed, and he did not care what people would say about him. He fulfilled his word. He did not give in, and did not utter even one word in Yiddish. He spoke Hebrew with everyone. If someone did not understand him – they would go and learn.

This behavior was strange in the eyes of the other children (whose day-to-day language was Yiddish), and therefore, they mocked him. One day they even hurt him. Meir went to the principal, Abrasha Olshansky, and told him what had happened. The children were called to the principal for clarification, and he rebuked them. Eliyahu Veinstein, the son of the cantor, and Motele Shneidman were among those who hurt Meir. As a sign of full regret over their deeds, the children decided to join Meir in speaking Hebrew. Several other students joined them within a brief period, and they founded the Bnei Moshe [Sons of Moshe] Society.

After some time, its name was changed to the Bnei Yehuda [Sons of Judah] Society, for the name of Eliezer Ben-Yehuda[1]. This was a society

[Page 145]

that was zealous for Hebrew, and only accepted into its ranks members who proved that they would only speak Hebrew.

It was not easy to join the society. One of the students would come and announce that he had decided to speak only Hebrew, and that he had spoken Hebrew for a certain time. After they heard his announcement, they told him to wait for an answer. In the meantime, they would send a group of students to spy on him and inform them whether indeed he spoke Hebrew at home, with the neighbors, etc.

I recall that I once went with a group of children for the final act of espionage about a student who announced that he wanted to join the society, and that his language was only Hebrew. It was clarified that he indeed spoke to everyone in Hebrew. However, the matter was suspicious, since his mother did not understand Hebrew at all. We visited him at night. We sat and chatted. When we left the house, one of us, Beryle Veinstein, a student in our class, remained there, hiding under the bed of the “candidate.” Nobody in the household noticed that, and Beryle followed matters from his position under the bed. Before he went to bed, he argued strongly with his mother, who did not understand him. He used various means, including threatening language, to explain his desire – and he did not utter one word in the vernacular. When Beryle saw the behavior and suffering of the candidate, he was convinced that he was fit to join the society. He immediately came out of his hiding place to the surprise of all the members of the household, approached the lad, tapped him on the shoulder, and declared: “You have been accepted!” (That is what the group did when it was determined that a candidate had passed the test.)

The society, the planning, and the various committees were run only by the students, under the guidance of the principal Abrasha Olshansky, who was full of satisfaction. His dream had been realized.

A member who was accepted to the society was not always certain about his membership. Members would supervise each other lest they stray, Heaven forbid. There is a story about my sister (a member of the society and a student in grade four or five). She had returned from an agricultural exhibition in the nearby village of Chovorsk. Because of her great impressions, she said to my mother, who did not understand [Hebrew], in Yiddish: “I saw there a giant ox with very large horns.” Suddenly, the heads of several of her classmates appeared from behind the window, and declared in Hebrew, “Speak Hebrew!” They escaped, of course. Because of their testimony, my sister was removed from the society to her dismay and sorrow.

The society, which at the end encompassed almost all the students of the Tarbut School, also left its impression upon the students studying in the schools based on other languages, and even upon the youths who were not studying – everyone joined the circle of Hebrew speakers. The wonder was actualized, and, having no choice, the parents also began to understand the language, some more and others less.

The news of the founding of the Bnei Yehuda Society in David-Horodok took on wings. The Hebrew schools in the nearby cities began to take interest in the matter. The two mockers, Eliyahu, the son of the cantor, and Motele Shneidman, later became the pillars of support of the society. To this day, I am surprised how Motele Shneidman, short in stature and thin, only twelve years old, spoke amongst men, and lectured in a convincing manner with enthusiasm. Eliyahu, the son of the cantor, was like him. They were both sent to make the rounds in the Hebrew schools in the nearby cities of Stolin, Luninets, and others. Their enthusiasm slowly caught on to the people of those cities, even though at the outset they did not believe what their ears heard: “How is it possible to speak Hebrew all the time?” “Do you even think in Hebrew? And when you wake up, are you first words in Hebrew?” they asked. We also asked such questions at the beginning of the formation of our society…

Translator's footnote

[Page 146]

by Yerachmiel Morstein, Ramat Gan

We are getting more distant from the era of the Second World War, when a third of our people were annihilated in a cruel fashion, including our closest relatives. Therefore, it is indeed appropriate to extend double gratitude to the dedicated activists, natives of David-Horodok, for their efforts to erect this memorial monument. To my dismay, my native town did not succeed in such. May your hands be strengthened!

The town of David-Horodok, with its Jews who are no longer, with their lives and customs, is typical of a large portion of the towns that I had visited and knew well on account of my work. The natives of that city were indeed blessed for their great dedication in the perpetuation of that path for our children. You should know, they are the place from where we were forged. Those good Jews did everything, but to our sorrow did not merit to be with us and to participate in the realization of their vision and our vision – the establishment of our state, to which they helped lay the foundations.

Already today, during the era of the rise of the state – most of the youth who were raised in the Land do not recognize the importance and place of the Diaspora Jewry from which we stemmed. To those youths, the concept of the Diaspora refers to weak Jews, lacking in power, afraid and trembling before all gentiles, who tear up decrees through the recitation of Psalms and fasting, closed in their four cells[1], awaiting the arrival of the Messiah… Our children cannot imagine for themselves that all the dreams and dreamers of the establishment of our state – the pioneers in all manners – stemmed from there, and that it is to their merit that we have attained that which we have attained.

As the director of the Jewish agricultural cooperative in Pinsk, founded by the I. C. A. [Jewish Colonization Association], I visited towns in the area and searched for the Jews. Outside my job I investigated their past. I arrived at the railway station of Lakhva in the spring of 1932, and began to search for a wagon driver to take me to Horodok. How great was my pleasant surprise when I heard one of the wagon drivers, a young lad, calling out bevakasha[2]. I did not believe what my ears heard, so I turned to the wagon driver and said, “Did you say something in Hebrew?” “Amnam ken”[3], he responded, and boasted that he was a member of Bnei Yehuda [Sons of Judah]. During the journey, he explained to me the purpose of the society that was set up by the youth in the town: to learn and speak only in Hebrew so that it will become the language of the masses in time, and not the heritage of a restricted group – mainly maskilim [followers of the Haskalah [Enlightenment] movement] – as it is today. To my questions as to whether this could be realized, he responded with self-assurance that he and his friends are very proud of their achievements to this point, and he would prove this to me when we reached the town. Indeed, he proved it to me, and I was convinced!

Their oath when they joined the society, to refrain from using any other language, was fulfilled with the enthusiasm that is typical of youth. The Hebrew language struck roots thanks to the stubbornness of these youths.

Translator's footnotes

by Mendel Kravchik

At the end of 1922, a youth dressed in festive clothing appeared in the town. Because of his clothing, it was immediately recognized that this man was foreign in town. News quickly spread through town that this man was a teacher who intended to set up a cheder in town.

The first deed of the teacher was to invite parents to a meeting in the home of Shlomo Rozman. Out of curiosity, several youths, including the writer of these lines, chose a hiding place in one of the rooms next to the meeting, and listened to what was taking place at the meeting. The young teacher spoke at length about the new subjects that he intended to enter into the curriculum: about his desire to teach nature, geography, and history. Many of the parents expressed their willingness to send their children to the new cheder. They even promised a means of livelihood for the teacher, and he decided to settle in the town. A few parents objected to the cheder, and regarded the changes and innovations as heresy and a deviation from the straight path.

[Page 147]

At the beginning of the studies in the cheder, the news spread that one should come with a head covering only for Bible classes. For the rest of the classes, one was to come with an uncovered head. The teacher introduced another custom – the obligation to knock on the door. This modern cheder was maintained by the teacher Branchuk until the establishment and renewal of the modern Hebrew school in 1924. He was appointed as a teacher there as well. Very many people studied Torah from him until he was imprisoned in 1941, starting from studies of Bible and ending in classes in history and music.

I remember our teacher when he appeared at the first music class with a violin in his hand. His appearance elicited our laughter. We were embarrassed to open our mouths, and he helped us by starting to sing.

He was my first counselor in the classroom at school. Every week, the counselor had to record notes regarding the behavior and studies of each student in a special ledger maintained by the institution. We had to bring these notes to the attention of our parents on the Sabbath, and they had to certify it with their signature.

Since we knew what would happen to us at home if our parents were to read negative reports, the writing of these reports served as an expert pedagogic tool. Because of this, along with the influences of his explanations, we were very diligent in good behavior.

He knew no weariness. His body was weak, but he bore the yoke of all the tasks imposed upon him. The number of students in the school was large. The school building of that time could not accommodate them all, so the classes were given in two shifts. He himself taught in both the morning and the afternoon. After the classes, he would organize the school choir and student performances, take care of the library, etc.

Aside from all this, he himself was forced to continue his studies, since the government educational authorities demanded a teaching certificate from him. Therefore, he had to prepare for the exams.

|

|

The pioneering Zionist idea slowly began to penetrate the circles of the older youth of the town. A Jewish National Fund brigade was organized, and pioneering youth groups were established, mainly from amongst the students of the school. In that period, the school was a “factory for the souls of the nation,” and the youth groups filled up what was lacking in it.

[Page 148]

Branchuk played a large role in the youth groups, and we always met him there, whether it was a “celebration of questions and answers” (in vogue at the time) or public meetings of the youth groups. He would always come, lecture, explain, and guide. He spared no effort, and often accompanied us on our hikes to the forest near Borok.

In the autumn of 1931, Branchuk was chosen by us as a delegate to the Tarbut convention in Warsaw, in which Ch. N. Bialik participated. Afterward, he gave over details of that convention with great emotion at a public meeting that was called in town after his return. He told us about the ways of the Zionists at the convention, and the lectures of the poet Ch. N. Bialik. Our emotions grew stronger when he told how the poet thundered against the leaders of the Jewish community of Poland by shouting, “Shkotzim – to the cheder!”[2]

In the spring of 1932, most of the youths were organized into Zionist youth groups. The older ones were registered for the most part in the Zionist parties, and we decided to demonstrate our collective power in the town through a mass demonstration that was to take place on Lag B'Omer. We also invited the youth groups from the nearby towns of Stolin and Lakhva. Almost all the Jews of the town participated in the demonstration. The students of the school marched at the front. Behind them marched the members of the parties and youth groups, with their flags. This was an impressive sight. The national flags fluttered in the air. The shirts and ties stood out from all sides. After several speeches delivered from the porch of Mordechai Rimar's home in the marketplace, we began to dance the hora. Branchuk, who by chance was standing next to me, told me with emotion, “Behold, this is Tel Aviv and not David-Horodok. We will yet merit to see the blue skies of the Land of Israel.”

The Soviet army entered David-Horodok in the autumn of 1939. The communal activists began to worry about the fate of the Hebrew school. The students were required to return to their studies after the vacation. The local authorities had not yet solved all the government issues in the town – so for now, there were no classes. Finally, a directive was issued regarding the ban on the Hebrew language. It is hard for me to forget the image etched in my mind: there are rows of students standing in the long corridor of the school, and the teachers were explaining to them that the Hebrew language is now strange to us – and from now we will learn in our mother tongue of Yiddish. Branchuk's throat was choked with tears as he said, “From now on, it will be good for us here, and we must not think about aliya to the Land.”

It was the night of February 11, 1941. I was among the prisoners arrested in the town that night. We began to surmise the reasons for the imprisonment. After they hauled in Shmuel Zezik and Kopel Moravchik – the political background, Branchuk suddenly appeared. Nervousness and fear overtook us. Aharon Moravchik burst out weeping, and Branchuk encouraged him, “The sun shall yet shine for us. Our only sin is that we were Zionists. We did not sin one iota against the Soviets. I am certain that they will free us.” He concluded his statement. After the end of the investigation, they transferred us from the interrogation cells to the central prison in Pinsk, and we met again. The cell was full of prisoners, mainly of the worst kind. We Jews found a corner in the cell and avoided all meetings and conflicts with the worst of them.

Branchuk approached them, explained some geography to them, and earned their appreciation. Things came to the point where they sat around us with special awe, listening to his explanation, and ensuring that nothing bad will happen to him or his belongings. Through his merit, we too were helped.

A sack of tobacco, like a treasure, was tied to his neck, and he gave some to whomever would request. They began to speak of his good heart with great admiration.

We were in prison in the heart of Russia, and the days were at the beginning of the Russian-German war. Soviet troops were retreating. There were alarms and bombardments several times a day – and we were locked up in a room. The prisoners began to guess, and some said, “Would it be that the enemy will arrive, and we can get out of jail.” Branchuk quietly expressed his opinion to the Jews, “Heaven forbid for us to think that the Germans will be our saviors. Even though we are prisoners, we must not request their arrival.” He spoke with fear about the fate of the families who remained in David-Horodok, “My heart tells me that the path that seems short – is the long path.”

[Page 149]

It was August 1941. We were once again brought by trains from the prison to the heart of Russia. Branchuk took comfort, “Perhaps there we will survive. Would it be that they will also bring our families.” That time, the journey was difficult and tiring. There was a serious lack of water. The food was salty, and when a flask of cold water was brought at one of the stations, people fought over it, and the strongest won. Branchuk became ill on the fourth day of our journey. According to the medic who was with us, this was dysentery and intestinal spasms. Those on the train treated him with respect and patience. We changed his clothing, and helped him eat, but his energy dissipated from day to day. We arrived in Kyruv on August 16, 1941. We received a notice to prepare to disembark. We dressed him in warm clothing. We packed his sack and took him off the train. It was difficult to recognize him. He was dying. We laid him down on the grass quietly. He was trembling all over. The policeman prodded us to join the ranks of the healthy ones who were continuing their journey on foot. I looked behind me to see where the grave of my teacher was being dug.

Toward evening, we met a Jewish doctor from Pinsk who certified his death to us. It took place about an hour after we took him off the train.

May his memory be blessed.

Translator's footnotes

(My Uncle Asher, Aunt Beila, and brother Abrasha Olshansky)

by Sara Rimar Olshansky

Father of blessed memory was a Zionist, and he did not want his children to assimilate among the gentiles. Therefore, he took us to Pinsk, so we would be among Jews, and mainly so we could study Hebrew.

I was seven years old at the time, and my brother was six. That night when Father informed me that he must part from us and return to his home will never leave my memory.

I wept bitterly all night, and my aunt and uncle were unable to console me. How great was our joy the next morning when we saw our father return to us. He did this intentionally. He wanted to see how we would behave in his absence. He spent a week with us until our aunt and uncle earned our trust, and our hearts began to love them.

We did not lack anything in our new house, including the love, dedication, and care of a mother. Our childless aunt dedicated her whole heart to us, and we returned the love to her bosom. During the time of the German occupation of the First World War, when the command came to register the population, our aunt and uncle registered us as their children – and from that time, we called ourselves by their family name.

Their dedication to us was exemplary. Even during the times of famine in Pinsk, when our uncle's material situation was quite poor since his entire business was in Kiev in the Russian zone, leaving him in complete lack – they went out to work in the fields at the risk of their lives so that we would not suffer, Heaven forbid, from want. Most of the children left their studies for the schools were closed, but we received our lessons from private teachers even during the difficult times. They dedicated their whole hearts to us.

We moved to David-Horodok, my uncle's native town, when the borders opened in 1918. I made aliya to the Land seven years later, and my brother Abrasha traveled to Vilna to continue his studies in the seminary. Abrasha knew that our uncle could not afford to bear all the expenses, so he tried to the best of his ability to earn a livelihood from giving lessons. Nevertheless, our uncle gave him the main portion of his sustenance. When Abrasha finished his course of studies, he started teaching in the Tarbut School of David-Horodok, and was appointed as its principal a short time later. He imparted the best of his strength and energy into the school. He was loved by both the teachers and the students. He won over souls for Zionism amongst the students, and organized the youth into his primary task: speaking Hebrew wherever they were. Even the parents were forced to speak Hebrew with their children.

In 1937, my brother visited the Land, and decided to return there with his family. However, the war thwarted his plans, and he remained stuck in David-Horodok. When the Russians entered the city, he could have moved to our parents in Russia, but he was concerned that such a step would put an end to all possibilities of ever making aliya to the Land. The Tarbut School turned into

[Page 150]

a Soviet school. Abrasha was fluent in Russia, but the new form of education was disappointing to his spirit. In one of his lectures on behalf of the authorities, he had to speak to the students and parents about the Soviet regime and the new education. He began his speech, but did not have the energy to continue, for tears choked his throat. It was difficult for him to preach Communism instead of Zionism. Thus, his fate was sealed. The new regime regarded him as an untrustworthy person. The period of his wandering and tribulation began. He was forced to leave David-Horodok, and he sought refuge in Bialystok, but there too he did not find rest. He moved with his family to Luk, and from there we lost track of them. Apparently, the hand of the murderers reached them there. May their memories be blessed.

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Davyd-Haradok, Belarus

Davyd-Haradok, Belarus

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2024 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 08 Jan 2024 by JH