|

|

|

[Page 235]

by Yakov Beker, Israel

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

The City Council was a communal platform in the true sense of the word. There were representatives in the City Council representing all political parties and communal groupings from Jewish and Polish society. The struggle of the opposing interests of these groupings was mirrored on the dais of the City Council.

Poalei-Zion was represented with a large faction from 1927 until the devastation of Chelm in 1939. During this period, elections took place three times and each time they came out stronger and with more support. The first City Council election took place in 1919. Because, Chelm had a Jewish majority, there was a “danger” that the City Council would have a Jewish majority. This caused great aggravation for the anti-Semitic supervisory regime. In the first City Council, Poalei-Zion was represented by Dr. Moshe Kanfer. The threat of a Jewish majority was avoided by a simple means: it was decided to annex the surrounding villages, such as Bazylany, Majdan, Wygun and Nowiny (a little village five km from Chelm). Thus, Chelm became a “real Polish city.”

Nevertheless the peasants from the little villages complained that they had to pay more taxes. However, it was clarified for them that they were fulfilling “an important national mission.”

An exceptionally intensive election campaign was carried out during the voting for the City Council on the 11th of November 1927.

Scores of gatherings, meetings and rallies were organized in the city's largest ballrooms on the part of Poalei-Zion. Representatives of the parties, the unions and the most active workers from Tz. K. [Tzukunft – Future] would appear at the rallies.

|

|

[Page 236]

The day of the election was a true mobilization of the entire Poalei-Zion multitudes, of the “youth,” “jamborees of scouts” and the P.Z. comrades from the surrounding shtetlekh. The election brought a victory for Poalei-Zion, having received 1,054 votes and electing three Councilmen: Mordekhai Erwi, Moshe Beker and Ahron Hipszman. Shmuel Szimel took the place of Erwi when he was chosen as an alderman and, later, he was replaced by Shmuel Barg.

The general results of the election were as follows:

| Poalei-Zion (Left) | 1,054 votes | 3 seats |

| (M. Erwi, A.D. Hipszman and M. Beker) | ||

| Tzeri-Zion | 319 votes | 1 seat |

| (Lazar Lederman) | ||

| Bund | 307 votes | 1 seat |

| (Hershl Fructgartn) | ||

| The Jewish “Red” | 287 votes | 1 seat |

| (The list was invalidated) | ||

| Artisans | 585 votes | 1 seat |

| (Israel Bursztin) | ||

| Jewish National Bloc | 1,349 votes | 4 seats |

| (Yakov Sztul, Y. M. Lederman, Yitzhak Bukhna and Finkelsztajn) | ||

| Total Jewish Vote | 3,901 votes | 10 seats |

| Polish Civil Bloc | 1,777 votes | 6 seats |

| P.P.S. | 2,559 votes | 8 seats |

|

|

||

| Total | 8,237 votes | 24 seats |

From the results shown above, it can be seen that the Polish workers in Chelm, the P.P.S. [Polish Socialist Party], scored a victory, too, receiving eight councilmen as opposed to six Civil. There was an ability to create a socialist city council and to run the city economy in the interest of the working masses from both populations [Jewish and Polish]. However, the Jewish and Polish workers received no satisfaction from the socialism of the P.P.S. The P.P.S. faction often joined the rightist Polish reactionary bloc.

At the first session of the newly elected City Council, the Town Council of five men was chosen: President – St. Gut; Vice President – Terfitz (both from P.P.S.); Alderman – Mordekhai Erwi and Feiwl Rozenblat (both proposed by Poalei-Zion) and one Alderman from the Polish Civil Club. Due to the protest of the rightist Polish Club, with the support of the Jewish Nat. Club, the election of the aldermen was invalidated. And at the second session of the City Council, it was shown that, in such a short time, the P.P.S. had gained complete control of the bloc, and with their votes, the Polish right received two alder-

[Page 237]

men and Jewish Chelm remained with one Alderman – Poalei-Zion representative, M. Erwi.

The Poalei-Zion councilmen were presented with a very difficult test; in order to take a position on all of the city council business they had to have knowledge of the questions of the city economy, budget and other very complicated problems.

However, the three Poalei-Zion councilmen were simple workers, had never even visited a middle school and had not properly mastered the Polish language. At first, professors, teachers, high officials from the rightist Polish bloc would look with mockery at the three men who did not fit at all into their group. The Polish anti-Semitic intelligencia would scoff because our councilmen spoke a Polish full of errors. In time this attitude changed. They were quickly persuaded that they had before them serious and uncompromising men; mockery against them did not help, nor flattery and they could not be frightened by threats.

It can be asserted with full reliability that there was no field that concerned the life of Jewish workers or any of the painful problems of Jewish national and social life that the P.Z. councilmen did not bring to the forum of the City Council. The P.Z. learned about the needs of the Jewish people in daily life. They described this need with their entire power on the dais of the City Council.

The former mockers noticed with amazement how the P.Z. councilmen began to show proficiency and insight about the most entangled questions of city economics, finances, the school and hospital systems, and so on.

The first clash came at the first solemn session (after the election for the City Council). At this session the representatives of various factions read their ideological declarations that were heard by everyone present. The representative of the P.Z. faction had just begun to read their declaration. At first, he read in the Polish language and then immediately changed to Yiddish. The Polish rightist councilmen began a dejected uproar. They would not permit such a “desecration.” The chairman, the peposovyetz [word derived from initials of the Polish Socialist Party – P.P.S.] Gut, interrupted the speaker, demanding that he leave the podium. He did not move from his place and ended his reading to the accompaniment of screams. He demonstrated in the open the struggle that P.Z. carried out for the rights of the Jewish masses; for the right of the Yiddish language. This was the first, but not the last stormy session of the Chelemer City Council.

The “ardent” sessions would take place when the yearly budgets would be dealt with for the city. During the discussion of finances and taxes, the P.Z. councilmen would demand that everyone living in only one room with a kitchen be freed from housing taxes; that the shopkeepers and artisans, who had licenses in the 4th and 8th categories, be freed from business taxes. They publicly came out against taxing cultural undertakings. Conversely, they would make motions to in-

[Page 238]

crease the taxes of the well-to-do, of the owners of large enterprises and large houses and to increase luxury taxes and so on.

In dealing with the medical and hospital systems, the P.Z. councilmen demanded full free care for the poor population. The P.Z. sharply protested against the particularly warm relations with the privileged neighborhoods in which the rich lived and against the step-motherly relations with the poor quarters in questions concerning the development of the city. Speaking about the Jewish institutions like the Jewish public school, libraries, TOZ [Society for the Protection of Health], Linas HaTzedek [institution for assisting the sick], and so on, the P.Z. councilmen would just indicate that the existence of the institutions was a witness to the depravations of the Jews because as citizens of the country they, of necessity, carried the burden of all of the expenses in the country. Therefore, it was the obligation of the state to take upon itself the full support of all of the institutions. Thus, they would make motions that the City Council should turn to the government about taking over the expenditures of all of the institutions and until this happened, the City Council must properly subsidize all of the institutions.

The motions did not always have the same fate. The greater number would be rejected by the majority. Certain motions would be accepted. In the course of the first term of the City Council, the Town Council carried out a series of measures that were accepted positively by the surrounding population. The P.P.S. found themselves under strong pressure by the P.Z. councilmen and the Poalei-Zion alderman. Polish workers were frequent visitors in the gallery of the City Council and would listen attentively to the utterances of the P.Z., and the P.P.S. often found themselves in an uncomfortable position. During the first term there was a successful fight for a series of grants for the Jewish institutions.

The P.Z. faction was in constant contact with its voters. There was an active faction office. The councilmen and Alderman Erwi would receive clients three times a week. The office was overflowing with Jewish artisans, poor shopkeepers, workers and women during the reception hours. They would submit pleas about taxes, about support; complaining about injustices against them on the part of certain officials. In great part, workers who had certain matters to discuss and not having any patience to wait until they would be received in the office would search for the councilmen at their workplaces or simply in the middle of the street and give their requests or complaints…

The Poalei-Zion faction would take positions from the podium of the City Council not only on local matters, but also regarding all events of general political life in the world and in the country.

When the bloody unrest broke out in 1929 in Eretz-Yisroel – provoked by the English – Poalei-Zion demanded that the City Council protest

[Page 239]

against English imperialism and grant 500 gildn to the Jewish victims. On 10/11/1929 a solemn session of the City Council took place dedicated to the 10th anniversary of Poland's independence. The presidium of the City Council wanted only to utilize the celebration for a ceremony and endeavored that no separate faction could express itself. However, Poalei-Zion would not yield its right. They read a declaration in which, among other things, they declared: “At every opportunity, the Jews of Poland contributed to the struggle that the Polish people carried out for their liberation.

“Today the Polish landowners and capitalists have the power and not the Polish workers and peasants; the Jewish masses are without rights. Therefore, we will carry the struggle further until the final goal of socialism.” P.Z. would read similar declarations at every appropriate opportunity. These “demonstrations” would create a great deal of bitter blood among the reactionary councilmen.

P.Z. would call frequent meetings at which reports would be given about their activities and all of the city's economic business would be discussed. There were enough stormy sessions, both of the City Council and the Town Council, and intense work was carried out. Scores and scores of motions were proposed by the Poalei-Zion councilmen and the Poalei-Zion alderman, and they courageously fought for them.

The Work of Poalei-Zion Alderman Erwi in the Chelemer Town Council

Mordekhai Erwi joined the P.Z. Party in 1927. He was in his blossoming years and demostrated energy and initiative as well as intelligence and education, and was thus accepted by P.Z. with great satisfaction because such people were much needed at that time. Therefore, it is understandable that when P.Z. had the possibility of having a representative in the Chelemer Town Council, they believed that Erwi would be the most suitable candidate for the office. At the first session of the newly elected city government, Erwi was given control of the finance department. It is hard to know if this was by chance or with a purpose. It is a fact that he was given the most difficult department with the most responsibility. He had to take care of the finances of the city while simultaneously representing the poorest section of the population.

M. Erwi actively began to study his new assignment in order to be able to use each paragraph for the benefit of the poor population. Possessing an extraordinarily sincere relationship with people, Motek Erwi very quickly became beloved by the widest strata in the city. Up to 10 Jewish officials and employees were employed by Alderman Erwi's department. This fact greatly pleased the Jewish population. The behavior toward the clients was also very different from the other departments – straightforward, non-bureaucratic. He would speak Yiddish to the Jewish clients.

[Page 240]

Alderman Erwi supported the struggle of the P.Z. faction in the City Council to free the poor population from taxes in a concrete manner. Thanks to the support of Alderman Erwi as finance director, hundreds and hundreds of requests asking to be freed from taxes would be forwarded to the province. Many of them would be dealt with positively and those that were returned with a refusal would again be sent with a new rationale. Alderman Erwi took an active part in the sessions of the Town Council and, returning to the dais of the Town Council, took a stand on the conduct of other departments with which he did not agree. This provoked opposition to him by the remaining members of the Town Council. They began a quiet, but stubborn struggle in opposition to him. This made him more popular and beloved by the Jewish population.

In one of the first sessions of the Town Council, an intense conflict broke out between Alderman Erwi and the rest of the Town Council members when he was dealing with a budget proposal calling for the Town Council to appropriate 15,000 zlotes for the unemployed; 15,000 zl. for the poor for heating: 5,000 zlotes for clothing Jewish children; 1,500 zlotes to open a trade course for the young Jewish unemployed trade workers; for the Jewish public school and children's home – 3,000 zl.; night school – 2,000 zl.; for the two Jewish libraries, for TOZ [the Society for the Protection of Health], Linat HaTzedek [organization caring for the sick] and the old age home – appropriate subsidies. Alderman Erwi strongly declared that he came to the City Council to defend the interests of the poor Jewish masses and, therefore, he would demand that the Town Council support the Jewish institutions just as it supported the Polish.

In connection with the census that was to take place on the 26th of February 1928, with a view toward apportioning the Chelm districts for the Sejmik [county legislature], the Town Council, at the initiative of Alderman Erwi, decided to send out an application in Yiddish to the Jewish population and thus Jewish registration commissars were employed.

The application in Yiddish was very warmly received by the Jewish population. Therefore, all of the Jews' enemies strongly resented it. The Endekes [Polish anti-Semitic nationalist party] and Kadekes [extremely religious anti-Semitic party] newspapers published the entire Yiddish application on the first pages of their newspapers with the appropriate aggressive, ludicrous invective toward the Polish middleclass of the city who had permitted it.

At the City Council meeting in October 1928, after the results of the census were used to increase the area that constituted Chelm in the Sejmik, a president was chosen for the City Council. The P.P.S., faithful to the lines drawn, then also joined the Endekes-Senatorial Club – creating a Polish majority and enabled the election of an Endeke chairman and

[Page 241]

a P.P.S. vice chairman. The Poalei-Zion faction delivered a sharp statement and left the session; later, the remaining Jewish councilmen did the same.

The following report was published in the organ of the Left Poalei-Zion in Poland, Arbeter Zeitung [Workers Newspaper], No. 3 of 1/1929 under the title, “One Year of the Poalei-Zion Fight in the Chelm City Council.” Because of the characterizations of the report we print it here without any changes: -

“Proposals that had as their goals to satisfy the needs of the local poor and the Jewish masses without means were filed by the Poalei-Zion faction:

Figures Reflecting the Activities of the Faction:

| Interventions carried out in the tax department | 902 |

| Of these, freed from paying the state-local taxes | 702 |

| Of these, freed from paying the city taxes | 200 |

| In the department of communal protection and aid | 127 |

| Received the ability to travel to the Warsaw and Lublin hospitals | 63 |

| Received support for unemployment | 53 |

| Freed of paying penalties for arrests | 11 |

| Interventions with the Town Council Secretariat | 87 |

| Interventions with the Town Council Presidium | 37 |

| Total | 1,153 |

[Page 242]

|

|

Alderman Erwi in his presentation against the budget at one of the sessions of the budget commission, demonstrated that Chelm is a city with a 60 percent Jewish population and that they benefit from the support and subsidies the least. According to the statistics, during the past year, from 1/4/28 to 31/3/29, 391 people benefited from the support given out; of these, only 28 were Jews. A child in the powszechna school [Polish primary school] cost the City Council 26.42 zl. for the past year. At the same time, a child in the Jewish school cost only 7.50 zl. His bold presentation, with his pointed exhibits, strengthened the hatred toward him on the part of his Polish opponents on the City Council and Town Council. However, this made him more popular with and more beloved by the Jewish population. However, his young effervescent life was cut short…

On the night of the 28th going into the 29th of July, 1930, he was murdered in his own apartment at the age of 31. The news about his murder spread lightning fast over the entire city in the dusky darkness of daybreak. The entire Jewish population of the city and also a portion of Polish labor were certain that this was a political murder and that a political opponent and courageous fighter for the interests of labor and the Jewish poor had been eliminated. Later, it was shown that this was just an assumption.

Over 10 thousand people took part in the funeral that was arranged by the Paolei-Zion party committee. Almost all of the businesses and workshops were closed until the end of the funeral. The city was enveloped in sorrow.

[Page 243]

The funeral procession stopped at the City Hall building. Eulogists spoke from the balcony: the city president [mayor] Gut, and, in the name of Poalei-Zion, Yankl Beker.

The representatives of the professional unions, the kehile and other Jewish institutions and Nator Wasynczuk, of the Ukrainian Peasants party – Selrab [Peasant Worker Party, part of the Communist Party in the Western Ukraine] – spoke at the cemetery.

At the conclusion of shlishim [the 30 days of mourning] a sad assembly took place in the city movie hall with the participation of President Gut; Zerubavel; Yakov Feterzeil of [the Central Committee of] Poalei-Zion in Poland;. Hershl Frukhtgartn – party committee of the Bund in Chelm; Izbicer of the Poalei-Zion in Brisk; Moshe Yermus – of the artisans – and Yakov Beker in the name of the Chelemer Poalei-Zion.

|

|

With the death of M. Erwi, the Poalei-Zion Party lost one of its most capable people.

The City Council, the first in which Poalei-Zion played such a role, was dissolved in 1933 after the audits of the city economy were carried out in the City Hall and in various departments. The president, vice president and two aldermen were dismissed from their offices. Only Alderman Frokopiak was left for a short time to lead the City Hall and, later, he was replaced by the state commissar, Gorszalkowski.

The new city council elections took place on the 20th of May 1934. It was at the time when the influence of Hitler began to penetrate the countries of Europe. Polish reactionaries and Fascism began to lift their heads. The persecution of labor intensified.

The Poalei-Zion Party ignored the arrests and provocations and carried out an extensive election campaign with meetings, assemblies and electioneering [from house to house].

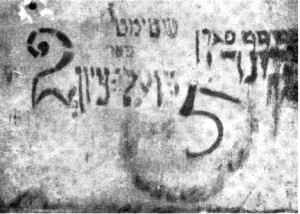

On the day of the election, extraordinary provocations were made against the Jewish voters at the election offices in the poor Jewish quarters. A document with a photograph was demanded of everyone who came to vote. [A document with a photograph] was not then common among large parts of the Jewish population. The work in the voting offices was intentionally prolonged and voters had to stand for hours before they had a chance to go into the voting office. When night fell, large groups of

[Page 244]

of hooligans came and chased off those waiting in line and succeeded in closing the voting offices. In such a manner, many hundreds of Jewish worker-voters were not permitted to cast their votes. However, Poalei-Zion received 1,140 votes, 100 votes more that in the earlier voting and elected three city councilmen. It was said that if not for the extraordinary chicanery, Poalei-Zion would have had five city councilmen. The general election results:

| Poalei-Zion | 3 city councilmen | |

| Jewish National Bloc | 9 city councilmen | |

| P.P.S. | 2 city councilmen | |

| Polish Civil Bloc B.B.W.R. [Bezpartykny Blok Wspolpracy z Rzadem – Non-Party Bloc for Collaboration with the Government) | 18 city councilmen | |

| Total | 32 |

Just as in the earlier election, at the call from Poalei-Zion, a multitude appeared; this time scores of meetings, assemblies and electioneering [from house to house] was carried out with complete enthusiasm. The results of the voting showed that P.Z. was not only not weakened, but the opposite; it received an increase of almost 100 votes.

Elected were Moshe Beker, Yakov Beker and Ahron Dovid Hipszman. Because the P.P.S. had a significant defeat and received only two councilmen, the City Council had an absolute rightist majority.

Therefore, the role of the P.Z. faction carried an exclusively oppositional character. Councilman Yakov Beker resigned from his office immediately after the first session, and was replaced by Berl Akslrod. Akslrod settled in Chelm in 1930, with his wife, Nekha, who also was a teacher with pedagogic training. He was the manager of the Jewish Folks-Shul [public school] and as a comrade of Stasz in the party, a man with education and knowledge of foreign languages; he quickly took a leading position in the P.Z. movement. He excelled in mastery of the Polish language and it was also

|

|

Second row: Fishl Iliwicki, Fishl Kopelman, Moshe Bojm, Zisha Kornfeld (Israel), Shmuel Szargel (Israel), Haim Bibl (Israel), Moshe Strojl |

[Page 245]

his fate to take part in the difficult oppositional struggle that was carried out by the P.Z. both in the city council and in the Kehile. He was a courageous fighter. For a time, he was an alderman.

The first session of the newly elected city council looked like a military parade. Taking part in it were the staroste [provisional governor] and vice president, the oldest priest, the president of the court and high military officials. (This was a hint that the communal institutions also were being created to serve the military leaders of the country.)

At the election of the Town Council, the candidacy of the lawyer, Tomaszewski, as president was made known by the Polish Civil Bloc. The Jewish National Bloc asked for a recess of 10 minutes and afterward declared that although they were not asked for their votes, they would, however, give their votes for the above-mentioned candidate. The Poalei-Zion faction announced an ostensible candidate, Comrade Yakov Peterzeil of Warsaw. The councilmen of the Jewish National Bloc also gave their votes to the candidacy of Pawliak, as vice president, although each of them knew very well that Pawliak was a public anti-Semite. Two weeks earlier as vice commissar, during a celebration by the city firemen, he ordered that one of them dress as a Hasidic Jew and that he should lay down with his bottom up on a cask of water and tremble and that this should be a part of the general march past the entire city. Understand that the excited Polish population was amused and ridiculed the Jews who tremble [from fear] of a fire…

It was necessary to have six votes to elect an alderman. The Jewish National Bloc had, with six votes, elected Abraham Szajn as Alderman. Poalei-Zion had their three votes and the two votes of the P.P.S. They received a refusal to their request that the Jewish National Bloc give them one vote so that there would be another Jewish alderman. And so, instead of another Jewish alderman being chosen, there was another Polish Endek.

The reactionaries grew bolder and cockier. A wave of anti-Jewish excesses began – pogroms in Brisk and in Pshitek, edicts against kosher slaughtering, separate benches for Jewish students, beatings by student hooligans in Warsaw streets, official anti-Jewish boycotts, supported by the government. (Owshem boycotts [Our Own, government policy of a general boycott of Jewish products and workers] were declared by the then Interior Minister Skladkowski.) Each day brought new edicts and oppressions.

On the dais of the City Council, the P.Z. councilmen expressed the accumulated cry of protest and rage of the Jewish masses. However, the Polish Civil councilmen were impertinent. They would heckle, interrupt in the middle of the speeches. There was even a case when a councilman, Rikhter Uminski, was threatened with prison. The P.Z. councilmen did not let themselves be terrorized, but continued their fight.

[Page 246]

The edicts that began to be strewn over the heads of the Jewish population in the country did not steer clear of our city. Many Jewish families were ruined by the edict against kosher slaughter. The boycott also was strongly felt. On market days, anti-Semitic young people would distribute slips of paper to the peasants urging them not to buy from Jews. There were even cases where hooligans would picket the Jewish businesses and not allow any Christian customers to enter. In addition to all of this came a new edict with the name “Urbanistic.” Under the cover of ostensibly beautifying the city, various ruses were invented to bring harm to the Jewish population.

This “Urbanistic” policycompletely ruined several hundred Jewish families in our city.

Fifty or 60 businesses were found on the so-called rynek [market] in the center of the city (on Lubliner Street), from which hundreds of Jewish merchants, retailers, artisans and workers drew their livelihood. Our local anti-Semites were conspicuous at this rynek and they decided to lay off workers because of “urbanistic and strategic motives…” The P.Z. councilmen immediately realized the danger, knowing precisely the political results expected by the rulers of the country. They understood that here no pleas and interventions would have any effect. Therefore, they proposed that the remaining Jewish councilmen immediately undertake a series of measures, such as threatening to leave the City Council and not voting for the budgets. (In order to support the extraordinary budgets, as well as in order to receive loans, it was necessary to have the votes of several Jewish councilmen.) The Civil Jewish councilmen did not accept the Poalei-Zion proposals. They hoped to repeal the edict in other ways, with other means. However, the edict was not repealed; all of the owners received papers asking them to leave their businesses. The owners of the stores and workshops did not want to voluntarily leave their spots, from which they had drawn their income for many years.

|

|

[Page 247]

Then firemen came and shattered the rynek with axes and hammers. This was a frightening and unforgettable picture: thousands of Jews stood with teeth pressed together and clenched fists and it was as if a pogrom had been staged against their possessions and the lives of several hundred families were ruined.

At one of the last sessions of the City Council, Berl Akslrod, the Poalei-Zion councilman, came out publicly with a very strong speech against the hypocritical politics of the city landlords concerning the Jewish population, with their speedy rush to tear down the rynek. Akslrod's presentation made a strong impression; as a result, the representative of the Jewish National Bloc, Yankl Sztul, delivered a statement that the stand of Poalei-Zion was correct and that they would support it. Moreover, he reported that the president had fooled and misled them (the Jewish National Bloc).

The session of the second City Council had ended long ago. However, no new elections had yet been set. The rulers of the country knew very well how much wrath had been gathered against them, particularly among the Jewish population. Therefore, they had to insure their leadership by entirely changing the voting methods.

New elections were set for the 20th of May, 1939 by the supervisory regime on the basis of the new voting edict, according to which proportional voting was created. The city was divided into six regions and was cut up so that the regions that were populated by the Polish population would provide the largest number of councilmen. Everything had been prepared so that the leftist Jewish councilmen would no longer have access to the city council.

The election month was during the month of May. In as much as it was a very beautiful and warm spring, all of the meetings took place under the open sky. The P.Z. meetings took place on the Neier Welt [New World] (Katowski Street), near Szwarcman's Square. On Shabbos,

|

|

[Page 248]

thousands of Jews would assemble on the Square and would listen with tension to the speeches of the P.Z. councilmen and other leading comrades. On the part of P.Z. this time, the best speakers were sent from Left P.Z. (Zerubavel, Mietek from Lodz and so on).

On the day of the elections, the Jewish voters ran into unending difficulties. Old Jews, men and women, would stand in line for hours and then not leave until they were able to give their vote. The results of the elections brought a great surprise: of the 3,907 Jewish votes submitted, the Left P.Z. and the Prof. Union received 3,031 and brought in 8 councilmen (a ninth was short a few votes). The Jewish Civil [Bloc] – 2; the P.P.S. – 8: the Polish Civil Bloc – 14 (this time 32 councilmen were elected). The workers again received the majority. The Jewish population expressed their appreciation to the P.Z. Party for their courageous and worthy struggle, which they carried on in the Chelm City Hall during the course of 10 years. Moshe Beker, Berl Akslrod, Ahron Dovid Hopszman, Israel Goldrajkh, Sh. Szener and Israel Berman (a shoemaker) were elected for the P.Z.

The matter of the elections hit the ruling clique like a thunderbolt. The elections were not certified for months. At the end, the supervisory regime announced that the voting was declared void in two regions (those in which the Jews received five councilmen – four P.Z).

The new elections for the regions were set for the month of … September. This picture is deeply etched in the memory of the writer of these lines: the 3rd of September, 1939, the first three days of the war pass. However, Hitler's battalions have already succeeded in penetrating deep into the country… The streets of Chelm are blocked by luxury taxis. Polish nobility, capitalists, high officials are rushing to the borders in order to leave the country quickly… On the symbolic spot on which the rynek earlier had been found, I meet Mr. Akslrod, who is going around and collecting signatures from the Jews, while notices on the walls of the Chelm streets shout out that the elections for the two regions have been declared void and that new elections will take place in two weeks… Mr. Akslrod does his work, although he immediately knew, as I and many others, that now no elections would take place.

Occupied with “beautifying” the cities, saving the “Polishness” of Chelm and other cities, they lost Poland…! The ruling clique that administered Poland until 1939 received its punishment. How horrible it is, however, that the innocent victims – almost all of Polish Jewry and among them, approximately 18,000 Jews from our hometown, Chelm – paid for their crimes and for the crimes of their former partners…

[Page 249]

by Hersh Handelsman

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

|

|

The Jewish Artisans Union in Chelm wrote an important page in communal life. It was founded in 1919, several years later than in other cities in former Czarist Russia, where a movement to organize Jewish artisans had begun in 1912. The idea of organizing the Jewish craftsmen arose because of the impoverished condition of the Jewish artisans in the Pale of Settlement. The invisible communal role of the Jewish craftsmen also provoked their striving to free themselves from their servility in facing the Jewish leaders in kehile life, who looked at the artisan as if he belonged to a lower layer of the Jewish population.

From the information I received from Josef Szperling, the Chelemer artisan-advocate, we know how the Chelemer Artisans Union was organized and about the first phase of its activities.

The first organizational conference was held in the house of Haim Atlas. This was after the First World War and the rise of the Polish state, which introduced democratic ordinances and gave equal rights to the Jews. The Jewish kehile began to organize on a more democratic basis; the so-called rich people no longer had an exclusive monopoly in kehile matters.

Immediately after the First World War, the architects of the founding of an artisans union began to recruit members within the walls of the synagogue and then the recruiting was taken to the houses, going from one artisan to the next. The registration of members took place at a fast tempo. Craftsmen from every corner of the city enrolled as members of the founding artisans' administrative body. Artisans from neighboring shtetlekh, who were driven from their residences to Chelm by the war, registered as members.

A general meeting was then called that among other points on the agenda proposed the election of a managing committee. In fact, a managing committee was elected at this conference with the following people: Israel-Yitzhak Nankin (chair-

[Page 250]

man); Welwele Milsztajn; Berl Kelberman; Lev Sztekn; Shlomoh Brustman; Josef Szperling; Josef Cymerman and still others.

At the first meeting of the managing committee, a plan of activities was presented and a motion by W. Cymerman to found a parts and work tools cooperative was unanimously accepted. The same W. Cymerman offered his shop as the place where the cooperative would open, emphasizing that he would not accept rent money.

This cooperative was quickly opened. In truth it was an enormous and important help for the poor artisans, who, before the development of the cooperative, had to pay high prices for all of the necessary parts and materials because of the instability of the exchange rate and the everyday rise in prices for all of the goods and of the tools and articles that were needed by the artisans. Because of the developing speculation and price instability, the artisan could not buy any goods and, as a matter of course, could not earn enough even for his poor way of life.

Simultaneously, cultural activities began among the artisans.

In 1921, the Artisans Union created a dramatic section and, although all of the members were family people, they took on the production of two shows from poems by J. Gordin: Khasye di yesoyme [Khasya the Orphan] and Der Gebrukhene Hertzer [The Broken Heart]. Both productions were a great success. The theater, Sirena, overflowed with a large audience that was eager to see how artisans act.

There was a court of arbitration even in the first phase of the Artisans Union and various internal disputes were taken care of in the best way. However, the Artisans Union went through many crises at various times. There was a shortage of money and there were times when there was not enough in the treasury to pay rent to the owner, Berish Kuper, in whose house the artisans' meeting hall was located.

|

|

The artisans' meeting hall was in Berish Kuper's house from the time of the founding of the union until September 1939. This house at Lubliner 27 was

[Page 251]

well known in Chelm. Lubliner Street was the main street in Chelm and Berish Kuper's building with the number 27 was also well known. The meeting hall for Left Poalei-Zion was also there and various social events and entertainments, splendid evenings and lively meetings took place there.

The artisans' meeting hall that was the home of the Chelemer Jewish artisans was located on the second floor and many craftsmen had their apartments there. Jewish life pulsed day and night in this house. Lubliner Street was a neighbor of Neie Tzal Street and Neie Welt Street that were thickly populated by Jews.

The artisans' union was an important economic-communal force that consisted of about 1,200 members. All trades were incorporated into the union such as furriers, tailors of women's and men's clothing, makers of ready-to-wear men's and women's clothing, construction workers, masons, house painters, furniture and cabinet makers, tinsmiths, copper and brass workers, locksmiths, shoemakers and gaiter makers, harness makers, butchers, watchmakers, goldsmiths, decorative painters and others.

Later, the following sections were divided according to the guild law: tailors of men's clothing, makers of inexpensive ready-to-wear clothing, tailors of women's clothing, seamstresses, hatmakers, furriers, a leather section, gaiter makers, shoemakers of ready-to-wear shoes, harness makers, tinsmiths, locksmiths, painters, glaziers, construction section, knitwear makers, carpetmakers, smiths, hairdressers, bakers, watchmakers, headstone carvers, metal workers and others.

The artisans organized for mutual aid and widows and orphans of artisans were provided with support. Loans would be made. When a cooperative bank was founded, the Artisans Union was represented in the bank by six or seven representatives. These were the artisan activists who were representatives in the bank: Shimshon Bursztyn (vice chairman of the bank), Wewtshe Handelsman (who was chairman of the shoe-

|

|

[Page 252]

maker section), Moshe Yermus, Shlomoh Brustman, Berl Kelberman and M. Rubinson.

The Artisans Union had representatives in all of the philanthropic institutions and in societies, such as: the interest-free loan fund, clothing for the poor, old age home, in TOZ [Society for the Protection of Health] and in other institutions.

The following artisan activisits were elected to the kehile: Haim Houzman, Moshe Yermus, Wewtshe Handelsman, Ezrial Kratka, Shlomoh Brustman. Ezrial Kratka and Haim Housman were on the kehile managing committee. Haim Houzman and Karp were also wardens. And when Nankin, for many years the chairman of the Artisans Union, died, Izrael Bornsztajn was elected chairman in his place. He was also elected as a councilman to City Hall.

The Artisans Union was active in all of the above mentioned institutions and reacted to unfair trade by various community activists.

The public meeting report in the January 15th, 1926 Chelemer Undzer Shtime [Chelm's Our Voice] (independent democratic weekly covering literary-communal and economic questions) can serve as a historic document about the artisans, as follows:

“Sunday, that is the 10th, a meeting of artisan managers took place in the Artisans Union meeting hall under the chairmanship of Mr. Nankin. In short talks, the managers, Housman, Kratka and Karp, pointed out the actions of the Orthodox councilmen, with the presidium at the head, who determined from their report that they had done everything wanted by the poor artisans. However, the times were already different and the Jewish artisans would take every means to oppose the will of those who take advantage of the economic situation of the Jewish artisans.

“The councilmen also pointed out the various vexations they had to endure both on the part of the Orthodox who spoke with one voice more than the other groupings and on the part of the Zionists, who, ignoring the understanding about mutual aid, constantly betrayed the artisans on every important question dealt with by the gmina [community].

“Councilman Karp pointed out the ridiculousness of the plan to build a Jewish hospital that would cost a colossal sum in such difficult times that the city would in no circumstance give and only because Mr. Biderman wanted it. On the contrary, one did not want to oppose the demand of the artisans for an artisan's school that could be achieved with a small sum of money.

“Mr. Nankin spoke afterward, pointing out that despite the fact that today we have an elected kehile, actions are still being carried out without the knowledge of the councilmen. People are taking responsibility on their own, making various decisions that are causing great harm to the Jewish population. And the speaker further said that it is unacceptable to participate in the production of city hall's city budget, as was done by the

[Page 253]

Messrs Biderman and Janovski who participated at a time when the Jews needed to avoid giving aid to the unjust existence of a city hall government whose term ended long ago. However, thanks to the indirect assistance of the Bidermans, the city hall regime continues to exist.

“The meeting was closed with a read through and unanimous acceptance of the following resolution.

“In the report of the meeting called together by the Artisans Councilmen, Sunday, the 10 of January in the meeting hall of the Artisans Union, under the chairmanship of Chairman H. Nankin, the following resolutions carried:

“Learning of the activities of the gemina by our comrade councilmen after 16 months of work

From this report, we see how the artisans' representatives — Nankin, Houzman, Kratka and Karp — strongly defended the respect and dignity of the Jewish artisans and

[Page 254]

reacted to unjust actions by the kehile in challenging a just tax system and a subsidy for an artisans' school.

A very complicated condition resulted when the Guild Law of 1927 was enacted in Poland. This law reestablished a series of old qualifications from the past with the aim of limiting Jewish entry into crafts. A difficult struggle was carried out to repeal this edict, but nothing was of help.

During the course of the years 1925-1927, preparations took place to issue these Guild Laws that threw fear among the Jewish craftsmen who imagined that they would not be able to legalize their workshops.

However, according to the Guild Law, all previous craftsmen were free of the substantial procedure of examinations. They only needed to go through a small examination of practical work, not any theoretical examination. The examining commission consisted of representatives of the administrative regime, of representatives of the Christian artisans and of the Jewish Artisans Union.

A socialistic artisans union was organized in connection with the Guild Law. Artisans – home manufacturers, who took work home from craftsmen or from enterprises – were members of the administrative body.

Thanks to the activity of the Bund, the home artisan enterprises were successfully freed from the Guild Law. This was a great relief for these artisans.

This socialist Artisans Union had approximately 50 members. The managing committee of the union consisted of the following people: Hersh Fruchtgartn, (chairman); Abraham Sztajnberg; Y. Mager; Hersh Handelsman.

In 1929 the Jewish Artisans Union organized evening courses for their members, wanting to give them a little education and professional knowledge in order for them to be able to receive permission to run their workshops legally.

|

|

[Page 255]

Many groups of artisans became guilds after their legalization and each guild had its own management. The chairman of the metal trade was Josef Fiszboim. A. Kornfeld and Kh. Goldgevikht were active advocates in this trade; W. Kornfeld and P. Grynberg were trustees.

|

|

Such guilds were established for other lines of work.

The most meritorious artisan advocates were: Berl Kelberman, Shlomoh Brustman, Moshe Jermus, Gershon Lustiger, Dovid Nisnboim, Haim Hoizman, Ezrial Kratko, Shimshon Bursztajn, Wewtshe Handelman, Yisroel Bursztajn, Ahron Sziszler, Motl Goldman, Khona Kamanszteper from Szelest, Y. Nankin, Icykowicz, Nodelman, Nusenkorn, Hercberg, Dumkop, Szteper, Figlosz, Gojwaser, Mager, Wetsztajn, B. Feldhendler, Abraham Berland, b. Grynwald.

[Page 256]

In 1931 a convention encompassing three poviats [counties] — Chelm, Zamoszcz and Hrubieszow — took place in the artisans' resource room. Approximately 150 delegates attended the convention.

The Jewish toiler, the Jewish artisan went through great difficulties in Poland. The enacted guild laws disrupted the development of Jewish crafts and, in addition, the abrupt higher taxes completely impoverished the Jewish artisan.

However, the artisans union eased the situation through the difficult times. It joined the populist Artisan Central in Warsaw that was under the chairmanship of Rasner and Noakh Prilucki. The artisan representatives from Chelm often would participate in the country-wide conference of Jewish artisans in Poland and they also were a contact with the general artisan cells in Poland.

The Jewish Artisan Union occupied a distinguished position in public Jewish life in Chelm and was an important communal organization that was of great use to the craftworker, defending his interests and inculcating in him the love and responsibility for the communal interests of the Jewish people.

[Page 255]

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

It can be said that Chelm played its role in Jewish life equally with all of the Jewish cities in Poland.

It is a shame that no statistical material remains that could tell about the cultural, school and library systems. However, that which is preserved in my memory will give witness and give the following details:

There was no library in Chelm until the outbreak of the First World War. The simple reader was exposed to the story books of Josef Itshe, Hinde's son (many of the survivors must remember him).

The best readers would be delighted with Peretz's Yom-tov Bletlekh [Holiday Pages] and other publications from the Yiddish library that were received by Mordekhai Dubkovski, Hebrew and literature of the Enlightenment from Yehuda Milner, may he rest in peace (incidentally, the latter, was one of the most beautiful personalities that Chelm possessed).

Starting in 1916 a Yiddish-Hebrew library arose from which developed the Hebrew-Yiddish library named after Y. L Peretz and the worker library named after Ber Borokhov.

[Page 256]

For a time the Bund and the prof. unions also had libraries that were under Communist influence. The Bundist library closed because of Bundist inactivity in Chelm. The Communist library – as a result of persecution.

The Peretz Library, with 500 readers and almost 6,000 books, and the Borokhov Library, with its 300 readers and almost 3,000 books, lasted right up to the last minute. There were a large number of Polish books in both libraries.

It should be remembered that Khishele Rozenfeld, a daughter of the “Horodler teacher,” continually led the Peretz Library. It was one of the best Jewish libraries in Poland as a result of her effort and energy.

There remains a fact which has not been clarified:

In 1945 thousands of Yiddish and Hebrew books from the Peretz Library were dug up from a chamber on Szienkewicz Street; who hid them is still not known after all efforts [to find out].

The dug out books were sent to Lodz by the writer of these lines and in 1946 they became the foundation of a P.Z. [Poale-Zion] Yiddish-Hebrew library in Lodz.

[Page 257]

The cultural work in Chelm between the First and Second World Wars was carried out in general by all of the parties and youth organizations that existed in Chelm. Reports on various problems were arranged. However, in the main, P.Z., whose literary judgments and other literary undertakings were renowned and were truly a respected contribution to the cultural work in the city, excelled during the entire period.

Chelm was one of the few cities in Poland that possessed a weekly newspaper. Even before the publication of the Chelemer Shtime [Chelm Voice], three issues of Aygns [Property; Possessions] (written) were published that took up 24 closely written sides and which dealt with real problems of that time.

Later, in 1924, at the initiative of Nakhem Goldberg, and with the assistance of Sheike Wajnsztajn (publisher-owner), the publication of the Chelemer Shtime began; it was published without interruption until the outbreak of war. Feiwl Fryd and Fishl Lazar were editors for a time. For such a city as Chelm, the publication of a weekly newspaper was clearly of great importance and if someone among the Chelemers abroad preserved the 16 years of publication of the Chelemer Shtime, it would be a terrific contribution to the research about the life of the Jews of Chelm during the course of the years 1924-1939.

One year, a newspaper was published in Chelm through the P.Z. under the name, Chelemer Folksblat [Chelemer People's Newspaper]. However, it was not able to exist for more than a year.

In general, both newspapers were important contributors to the Yiddish press in Poland.

For nearly two years, Hersh Goldman also published the Chelemer Woknblat [Chelemer Weekly Newspaper] with advertisements and a section about the life of artisans in a smaller format than the Chelemer Shtime.

After the First World War, the question of a “Jewish secular school system” was placed in the foreground.

In Chelm, too, a kindergarten and Jewish school was created. It was inter-party at the beginning. It remained this way until 1927. Later it was led by Poale-Zion. Children from the poorer environment continually studied in the school. The Messrs. Hershl Frukhtgartn and A.D. Hopszman made important contributions to the school.

In 1939, the construction of its own building was started. However, the Hitlerist murderers destroyed everything.

A Jewish gymnazie in the Polish language also existed in Chelm from 1918 to 1931 that struggled continually for its survival.

[Page 258]

|

|

In the center, F. Zigelboim |

A “finishing school” also existed in Chelm that also had started to construct a building just before the outbreak of the war.

It still can be said that the competition in the field of education in Chelm was first class.

A dramatic section at the Jewish intellectual club and at other community institutions was active in Chelm between the two wars.

Feiwl Dreksler (perished), under whose leadership the dramatic section stood for a time, must be remembered. The sections principally gave and staged plays from the Yiddish repertoire. In addition, from time to time they produced things from unfamiliar repertoires. There were many associates in the development of the dramatic sections during the first years of their existence: Moshe Klerer (now in Brazil); Reizele Kelberman; Serka Citrin-Ziskind (perished); Abraham Bernfeld (living).

There were also musical sections led by Dr. Walberger, Josef Goldhaber, Tuvya Klajner (all perished) that assisted the dramatic circles, and from time to time, appeared in concerts.

Our singer, Dora Dubkowski, appeared in concerts all over Poland before the war (perished);

Ida Hendl, the famous violinist, is one of ours.

From these notes, it can be seen that Chelm gave worthy contributions to Jewish life in Poland. There are no more Jews in Chelm. The Jewish community has disappeared forever, just as it disappeared from the other communities in Poland.

However, during the time that Jewish Chelm lived, there is nothing to complain about – it was one of the most beautiful Jewish communities in Poland.

[Page 259]

by Yisroel Aszendorf, Buenos Aires

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

There was a Chelm with skhus oves [ancestral merits invoked in the interest of descendents.] A Chelm underground. This was the Chelm that had pulsed for many years with a strong Jewish communal life, with political parties, with cultural institutions, with a rich reserve of cultural people who did not only provide for their own needs, but provided for other Jewish settlements, even my shtetl [town] that was far away near the Russian-Romanian border to which came a Hebrew teacher from Chelm (Moshe Lazar). He taught me Tanakh [Hebrew Bible] and modern Hebrew literature and stimulated me into making my first poetic attempts.

I know, too, about the widespread activity of the various Chelm landmanschaftn [organizations of people from the same town] around the world, but I will now dwell on another Chelm, the Chelm that lives crying [through the] jokes – about Chelm's merits.

Every Jew liked to hear a joke every once in a while. Others liked to tell jokes, but there were many Jews who also liked to create jokes. Almost ever shtetl had its own clown or creator of witticisms. However, the majority of them did not cross the boundaries of their shtetl. Only a few did cross and also took their towns with them, such as Hershele Ostropolier and Efraim Grajdinger. However, the shtetlekh did not play any particular role in their stories. The heroes were Hershele and Efraim, the people, the individuals. The only city that remains in the history of Jewish folk-humor is Chelm. Chelm alone was the hero and not an individual, but as a community at large.

A number of stories and anecdotes were assembled over the course of many years. Did they really happen in Chelm and not in other Jewish communities? – This is not very important. What is important is that they exist. Are some of them rooted in the humor of another people? – What is important is they were made Jewish by Chelm. Those that are told about Chelm are these stories and no other.

The foolishness of the Chelemer [person or people from Chelm] is not foolishness that comes from maliciousness, although there can be a maliciousness in such foolishness that goes with goodness, with naivety. The Chelemer are not people who make fools of others; they fall victim of their attacks. Thus the Chelemer became similar to the Don Quixotes who always were ready to help other people and thus catch many blows from fate and from people.

The Jewish joke is in general a joke that bites, that jabs, that burns – pepper and salt. Chelm humor is a naïve one, mild, not a joke of deceiving and swindling, but of the deceived and swindled. And this is the main thing: the Chelemer is not satisfied with the skeleton of the joke, but clothes it in flesh, fills him with the blood of the story.

[Page 260]

Let us take the first story:

The first snow fell in Chelm, covered the autumn muds and the moldy roofs of the houses. What a light for the eyes! Then what? When the shamas [sexton] goes to wake the Jews for prayer, he will disturb the beautiful, white and fresh snow, make it dirty. The Chelemer worried and sought a solution for how to avoid this. The end of the story is not important. The Chelemer decided to put the shamas on a table and four Jews would carry him. This anecdote is important because the Chelemer strive for purity, for beauty.The second story:

The Chelemer shamas became old and weak. The Chelemer thought about what they could do so that he would not have to go every morning to knock on the shutters and drag himself on his sick feet through the wet, muddy alleys.Story number three:They decided to bring the shutters to the synagogue. The shamas would knock on them there and not have to drag himself and lose his strength. What kind of characteristic trait is revealed here for us in the character of the Chelemer? – Pity.

A Chelemer bought a sack of feathers at a fair and dragged it through a field to Chelm. On the way he suddenly had an idea: the wind was blowing now in the direction of Chelm, so why should he carry the load on his back. He would let them go with the wind. The wind would bring them home to him.Here we see how the Chelemer even trusts the wind with his property. The Chelemer believes.

I will mention the famous stories in which the Chelemer go through the world to find justice.

The various stories reveal for us the soul of the Chelemer, the soul that longs for beauty, that is full of mercy, that possesses belief and that searches for virtue. Oh what positive character traits the Chelemer possess!

True, the Chelemer seldom attains his goal; he constantly suffers defeat in his quests, caves in, but that is the fate of the honest and just in this world most of the time.

Various Jewish writers have tried to make artistic improvements to the Chelm stories, each in their own way. Did not Sholem Aleichem use Chelm as a pattern when he created Kasrilevke? Did he not see the Chelemer when he made the small people stately with great ideas?

Hundreds of Jewish cities and shtetlekh [towns] in Poland disappeared. But the heavenly Chelm was not annihilated. Chelm was created from the Jewish nation and it will continue to live like the nation. With our departure from Poland we took with us so much pain and misfortune. Of course, without a doubt, we need a little joy. Therefore, let us tell the stories about the good- natured, naïve Chelemer Jews again and again.

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Chelm, Poland

Chelm, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 19 Feb 2021 by LA