|

|

|

[Page 132 - English]

by Abraham Levite

At the beginning of January, 1945, just before the closing down of the sinister Auschwitz camp of annihilation, a group of young men decided to compile a collection by that name which would include poems, impressions and descriptions of what they had seen and felt there. The copybooks, in several copies, had to be hidden in bottles in different hiding places at work, outside the camp and then to be entrusted to some honest Poles, friends at work who were asked to retrieve them after their liberation, dig them up and give them into Jewish hands.

Like the other inhabitants of the Auschwitz camp these youths were convinced that they would never get out alive. The projected collection was to have mirrored their torments, given expression to their anguish and served as a kind of justification of their existence which they regarded as a shameful mockery in the light of the terrifying slaughter and the horrors with which they were surrounded.

The book was also meant to include a lot of material, facts of historical importance and descriptions of life in the ghetto and the abomination perpetrated by the Nazi killers there, before the imprisonment in the camp.

Some fine Hebrew poems by a Hungarian poet were already written down; there was an apology in letter form “To My Brethren in Eretz Israel:” and more.

Nothing came of it all as a fortnight later the camp was evacuated because of the approaching Russian forces. The written matter was left with the writers and the paragraphs appearing below were supposed to have been an introduction to the collection.

The text has been left intact as I regard it as a document written in Auschwitz about Auschwitz. Observations made of the death-camp by its inhabitants express the feelings of many brothers and sisters in the calamity, and as such are of certain value.

(Rouen, France, June 14, 1945)

[Page 133 - English]

I have read somewhere about a group of people who set out for the North Pole, only to have their ship stuck in a sea of icebergs. Their cries of S.O.S. went unheard, their food was gone, the cold pressed on them like a vise and, cut off from the world, hungry and frozen – they awaited their death. Yet for all that, they never let their pencil drop from their frozen fingers, continuing to make entries in their diaries on the verge of annihilation.

I was deeply moved when I read how these people, whom life had rejected so cruelly, abandoning them to the jaws of death could still transcend their predicament and go on doing their duty to posterity.

All of us who are going to our death in the midst of humanity's indifference, cold as the icy wastes of the poles, we who have been forgotten by the world of the living, -- still feel the need to bequeath something to posterity. And if these will not be perfect documents, let them at least contain some smattering of what we, the living dead, thought and felt, pondered and spoke about. Upon the graves in which we are buried alive the world is celebrating a witches' Sabbath in a satanic dance; the beat of the feet smothers our groans and our cries for help. By the time we are taken out of our graves we will have been asphyxiated, non-existent, dust to be dispersed over the seven seas. Then every man of culture, of decency, will think himself obliged to grieve for us and eulogize us. As our shadows flit across the cinema screens, sensitive ladies will wipe their eyes with their perfumed handkerchiefs and weep for us: “Oh! The poor creatures!”

We know: we shall never get out of here alive. The devil himself has written on the gate of this inferno: “Abandon hope, all ye who enter here!” We want to confess, a “Shma Israel” for the coming generations. It will be the confession of a tragic generation, one that did not betray its destiny, a generation whose feet weakened by rickets crumpled under the heavy weights of the torments which the times have piled upon their shoulders.

And so: we are not interested here in minute details or figures, the collection of dry data. Others will do it without us. The history of Auschwitz can be compiled without our help. Pictures, witnesses and documents will recount how men died in Auschwitz. What we want to do is show how people “lived” in Auschwitz, describe an ordinary, average working day in the camp. A say in which are interwoven a tangle of life and death, of fear and hope, of despair and a wish for life. A life in which one moment never knows what the second one will bring. How, with a sledge-hammer, we dug and scattered blocks of our own lives, bleeding blocks of youth, loading them gasping upon the freight car of time as it creaks along heavily on the iron lines of the camp conditions. And in the evening you unload it, tired unto death, emptying the car into the bottomless pit. Who will dredge up this horror-filled night, this blood-dripping day, all shrouded in shadows, out of the pit in order to confront the world with it?

It's true that some people will leave this place alive – non-Jews. What will they tell the world of our lives? What do they know of our sufferings? Indeed, what did they know of the Jews' anguish in the good years? They knew we were a nation of Rothschilds. Even today margarine wrappings and sausage peels are zealously collected as proof that things weren't so bad for the Jews in the camp. They would not be inclined to delve into the garbage cans of their memory to re-create those pale, dead-eyed shades that crawled along, silent and in constant fear, scratching the insides of the soup bins with their bluish fingers, to be driven away again and again and pick at the garbage, seeking a mildewed crumb of bread? Who would remember those miserable creatures, flickering like candles till they died away without having achieved their one and only ambition – to eat their fill just once? Then there were the thousands dubbed “Musulmen” by the camp, those whom every self-respecting functionary in the camp deemed it an “Auschwitz principle” to assist in… dying. It was these weakened, helpless and anonymous thousands whose pathetic shoulders bore all the tribulations, the sadism and horrors of the camp. They were forced to bear it all, even the sufferings of those more privileged until, at the end of their tether, they stumbled and fell, to be kicked away like worms by the shining boots of a Kapo.

They will not recount all this. Why depress everybody and invoke the ghosts of nightmares, especially as their own consciences were not too clean…? Better speak of the solitary few they knew who ate their fill. In this sea of torment and carnage they prefer to see the drops of oil floating upwards, the remnants of a sunken ship. Yes, as we bite our own flesh with

[Page 134 - English]

our teeth they say that we have plenty of meat, and when our parents are beheaded they envy us for the clothes we will be able to sell.

Our only resort is to speak of ourselves, though we are well aware that we lack the strength needed to write, to create a mirror that will reflect and express our tragedy. But this writing must not be judged on its literary merit. It must be regarded as a document, with due attention paid to the place and the time. The time is just before death; the place – the gallows. Only upon the stage is the artist expected to scream, weep and groan according to all the rules. After all he is not in pain. Who would criticize the actual victim himself for groaning too loudly or weeping too softy?

Though we are fumblers from the literary point of view, yet we have something to say. Even those who are utterly mute are not silent in their pain; they scream, albeit in a language of their own, the language of the mute. It is only the “Bonches” (reference to the Bonche Schweig by Y.L. Peretz, ed.) who remain silent, pretending to the guarding God knows what shattering secrets. Only in heaven, where no pose or pretence is tolerated, do they admit the secret of their life – a longing for a buttered bun!

The game has come to an end. A giant project has been finalized, one that will stand for generations: Judea has been obliterated from the face of the earth. The fire is being put out in the crematoria, the chimneys are dismantled. These are the monuments to the new civilization of Europe, the model buildings of the modern Gothic style. All are washing their hands, preparing for the benediction of “Kissui hadam” (covering the blood). Why not? After all there is no fear of a lack of covering ashes with five such crematoria shedding light all around!

And the slaughter was almost humane!

It is a splendid summer's day. A train of Displaced Persons made up of animal freight cars is making its way, its hatches barred with barbed wire. A stalwart soldier stands upon every step. A little child peeks out of one of the hatches, face beaming and bright brown eyes, all curiosity and courage. He knows no evil and what unrolls before him is an enormous book of pictures, open and stylized. There are colorful fields and meadows, and as the train moves on there are forests and orchards, houses and trees, all flying by, surrounding one in a half-circle only to disappear. The colors combine into a single splash, swirling for a moment and then gone. Tiny people and horses – living, moving toys which yet remain in one place. But the place itself is moving – where is all this going?

Suddenly, noisily galloping along, comes a train, black as the Devil himself. It hides the view, obliterates the sun and puffs out a choking smoke… Its cars rush along, trying to catch each other… Uniformed men can be seen through the windows. They appear strange, black-clad and smoke covered; they bode harm… Ah, the smoke, it hides even this. Finally the train passes. The picture repeats itself. Fields and forests, meadows and gardens, mountains and valleys flowing calmly and tranquilly be as if strung on a giant ribbon, only to disappear somewhere in the far distance… hovels and fences, trees and telegraph poles stream along as if swept by a giant current, everything passes, moves and lives. Strange, it is like some Mother's fairy tales… Where is it all going?

Inside sits the mother, head between her hands and her face bereaved. Her heart is beating strangely and her whole life seems to pass before her: childhood, youth, the short and happy family life, a home, a husband and a child. She sees her parents' home, the shtetl, the fields and forests. Everything rushes by, confused as in a pack of shoveled cards. Picture follows upon picture and all are marked with a black stain: the spacious apartment left abandoned – a family nest destroyed, doors and windows broken, smashed cupboards and kitchen utensils, trampled clothing. All this has been left behind and what now? Gewald! Where are we going?

The train crawls along at a slow pace, as if showing a last respect for the victims. After some ten minutes it returns empty. The Jewish plutocrat and the Bolshevic Jew, who had combated the Aryan world, hoping to destroy it, no longer endanger anybody. A goods' commando unit is already loading the clothing, still warm, upon the trucks…Los! Los! Somewhere in the land of the Huns a little Cain was born to order, to serve the state. The Reich's treasury pays him well for his work. Krupp has already prepared a gun for him. It is for his sake that Avremeleh's shirt, lovingly embroidered by his mother, is being transported.

And the world? The world, of course, is doing its very best. Questions are submitted and protests made; Committees of 5, 13 and 15 are held. The Red Cross holds out charity boxes, “Tzdaka tatsil mimavet” (charity will save from death) and the

[Page 135 - English]

radio and the press mourn for us. The Archbishop of Canterbury holds a prayer for the dead, and “Kadish” is said in the churches. Smug, complacent little men raise a glass to each other, wishing good luck to the souls gone to heaven, “and life and salvation for us…”

The rope is on the neck. The hangman is generous, he has plenty of time and so he plays with his victim. From time to time he downs a mug of beer or smokes a cigarette, smiling with pleasure the while. Let us exploit the short respite while the hangman is gorging himself. With the gallows as a writing table we will write down what we have to say.

Well then, comrades, write! Let your writing be concise and to the point, short as the days allotted to us and sharp as the knives thrust into our hearts. Let us leave a few pages to “I.W.O. Bletter,” to the Institute of Jewish Suffering. Let our brothers who have been spared read them and perhaps learn something from them. And to Providence we pray:

May it please You, who DO NOT HEAR our cries, to at least guard these chronicle of our tears in a special urn so that they will be preserved, fall into the rights hands and find their redemption.

Avraham Levite

(Published in Yiddish in the “I.W.O. Bletter”. New York, spring of 1946. Translated by Herzlia Dobkin)

In Hebrew in the book “People and Dust – The Auschwitz-Birkenau Book” by Y. Gutman, researcher of the Holocaust. Excerpts from the Introduction were quoted by the late Ben-Zion Dinur, Minister of Education and Culture, in his speech before the Knesset on May 12, 1953 on the occasion of the passing of the law of “Remembrance of the Holocaust and Heroism – Yad Vashem” by the Knesset.The Minister's speech and the above excerpts have appeared in the book “Alumot” for the eighth year of studies in the schools. “Messilot” edition.

[Page 136 - English]

by Chaim Bank

One summer day in June, 1979, while reading the National Jewish Journal “Algemeiner Journal”, I came across an advertisement from a travel bureau containing detailed information regarding a trip to Poland; the purpose of which was to visit the holy graves of the Hasidic rabbis, simultaneously designated with the names of the “shtetlech”, for example, Novy Sacz, Bobow, Rymanow, Dynow, Lancut, Lazajak, etc.

I became disturbed by the idea and was unable to calm down, it weighed so heavily on my mind I kept asking the question why? Why that restriction? Why only a tour to the graves of the rabbis? They actually died of natural causes. Why not visit the massive graves of my people, our martyr “Kdoshim” who were brutally and tragically cut off from their lives with the greatest cruelty by the German murderers?

Since I was not in a condition to visit all the massive graves, I decided to see at least the grave of my sisters and brothers the “kdoshim” martyrs from my native “shtetl” Brzozow. A warning came from my good friends and family not to undertake such a risky enterprise, based on fact that even at the present time Poland is not a safe place for a Jewish person. Disregarding all warnings, I resolved to undertake this trip. Just to assure myself and to keep my family from worrying, I took my son Dov (Bruno) for my companion, thinking also that while traveling we would visit other places besides my home town Brzozow.

On my way to Poland I wondered if I would be physically and mentally strong enough to be able to visit my “shtetl” Brzozow, which to us is now only the remains of a cemetery. There came to my mind recollections about the “shtetl” Brzozow, where I was born and grew up. I thought of my family, my teachers from the Hebrew and the public school; my friends, various organizations, the synagogues, and in general, the “haymish” Jews from the town with whom I had been in contact every day, sharing with them joyful occasions as well as those of sorrow… They are now “kdoshim”. The majority of them remain in the massive grave located in the forest in Brzozow.

In addition to visiting my home town Brzozow, clearly it was important to stop in Warsaw. There we visited the Jewish Historical Institute, the Jewish Cultural Society, The Monument of the Ghetto Warsaw Resistance, The Movement of Mordecai Anielewicz. We became reacquainted with the city erected from the ruins.

From Warsaw we traveled by train to Katowicz to meet the two sisters, daughters of the late Dr. Selenfreund, who presently resided there. We spent an entire day with them in conversation, reminiscences from the past; emotional memories. We received from them very useful information regarding our visit to Poland.

We left Katowicz for Krakow, the city I remember so well from the past. The center of the city remains untouched; only some suburban areas and peripheral city streets have changed from their previous appearance. At the present time several hundred Jews live in Krakow, but they are not visible. It is very hard to find a Jew on the streets of Krakow. We visited the temple where the late Rabbi Dr. Joshua Thon had been the spiritual leader.

From there we went to the “Rama-shul” (Rabbenu Moshe Isserles). At the rear of the “shul” the cemetery which, has been in existence for over five hundred years, is still present. Still legible on the monuments are the names of the righteous “Tzadikim” and important scholars from past generations. I was amazed that the German murderers had left this cemetery intact; however the public cemetery in Podgorze was completely destroyed. They built a wall from the gravestone monuments facing parallel to the “Rama shul”, but the names of the deceased are still visible on the monuments.

Here we had the privilege of meeting two old Jews who came from time to time to take a look at the “shul”. Both places, the “Rama-shul” as well

[Page 137 - English]

as the temple are very much neglected. Only on Friday evening for Sabbath services came one or two “minyans” (ten persons) to each synagogue.

On a street corner near our hotel, Hotel Francuski, my son noticed a sign, written in Yiddish, “Jewish Cultural Association Club”. We stepped in. The entire hall was filled with card players. I asked if there were any Jews among the people, the reply came, that only the woman in charge of the office was Jewish. Encouraged by that we stepped inside the office. There we received a warm reception; she only regretted the existing circumstances.

We also visited the suburban town Plaszow where the there had been a large concentration camp in which my brother Meir and other young men from Brzozow did hard labor. Nor did I forget to visit the locality of Kobierzyn where I had been interned in a prisoner-of-war camp for six weeks.

All the streets in Krakow, where the majority had been Jewish inhabitants, especially in the so called “Kazimierz Market” and its surrounding streets, which once were the center of Jewish life, were now transformed into a scene of death. The streets which used to swarm with Jewish trade and commerce, where you were able to touch the very pulse of Jewish life, where the “hu-ha” and hustles and bustle put the town into motion, where the turmoil set the tune - everything belongs now to the past. All is taken over by “others”, the “heirs” of the Jewish prosperity, but around them everything looks asleep. There is no sign of the dynamic, the impetus the rhythm, the spirit and the accomplishment typical of Jewish spiritual enterprise. The city of Krakow has been transformed into an ordinary provincial town. This I have witnessed and evaluated with my own naked eyes.

In the early morning we rented a taxi and left for Oswiecim (Auschwitz), the well-known extermination camp for the systematic slaughter of European Jewry. There we spent the whole day.

It is very difficult to describe the mood and state of mind, while visiting such a German “Culture Institution”. Better leave it to the reader's imagination…

The first deplorable scene was the “gate” through which the trains with their unfortunate Jewish victims, men, woman and children arrived. At the gate was the shocking inscription “Arbeit macht frei” (“Work creates freedom”). The cynicism of these words is beyond belief.

A film was shown to us about the liberation f the camps by the Soviet army, presenting the liberated human skeletons. Even a blind person would be able to see that the victims were Jews; however, in the explanatory part of the film the narrator talked about the various nationalities, among them “also” Jews.

We also visited the “Cultural Establishment” the Germans built in Oswiecim. The gas chambers, the crematorium, the rails on which the trains rolled in with the victims; the barracks in which the “hoftlinge” (those taken into custody) were concentrated, the chambers for special punishment where the Germans tortured the unfortunate for their “sinfulness”; and the “Apel Platz” (counting ground) where the victims had to appear twice a day by command of the German murders to be counted by the German woman in charge of “overseeing”.

The most moving impression was the sight of mountains of human hair, particularly women's hair, gathered in piles, children's shoes, and suitcases with the names and addresses of their unfortunate owners. I, myself, counted over two hundred Jewish names

|

|

[Page 138 - English]

from several countries - Greece, Yugoslavia, Hungary, Germany, Czechoslovakia, Italy, etc.

We also visited the barracks in which the “Jewish Museum” is now located; a very few Jewish exponents can be found there. It appears to be a poor tourist attraction. Upon my question, “why was the leader of the visiting group passing by the Jewish Museum?” came the reply “that this could be obtained by request from the tourist group through their guide.” To my second question, “is a visit to other barracks also based on the request from the tourist to his guide,” I got the following answer, “I'm only an employee, unable to answer your question,.,”

With a shaken heart we arrived at the neighboring camp Brzezinki (Birkenau) where the slavish life of the Jewish women was of the most deplorable. It is very hard to describe these women's suffering with the most deceptive conditions of hard labor under the clout of the German whip and revolver. They were waiting for redemption which came, however, in the form of gas chambers and extermination in the crematorium. Even now you can see several of these “barracks” where the unfortunate victims waited for their final liberation…

We entered the town of Oswiecim, once a real Jewish “shtetl”, now you would be unable to find there a Jew even for a “refuah” (medical cure).

Full of grief and saddened by our experience we returned to Krakow for two days. After that we left for the final destination, my “shtetl” Brzozow. We left Krakow by an express train to Rzeszow and from there took a bus to Brzozow. The closer we approached the “shtetl” the more I was beset by all kinds of unpleasant thoughts. We passed the well-known villages near Brzozow - Blizne and Stara-Wies. Already nearing the Christian cemetery, we were able to observe changes in the “shtetl. At last we were in Brzozow.

The bus station is located between the parish and the lower part of the court building opposite the little park. Upon our arrival we went to a hotel located on the ground where Dr. Pilshak's house stood. It is near the drugstore of the late Mendel Trinczer. After refreshing ourselves with a shower we took a look around the “shtetl” and at the existing changes. As I passed the Polish pedestrians no one recognized me. We went to the sidewalk near the court and church; here already there were changes. A few small Jewish houses across from the church, which had belonged to the late Hershele Ratz and Ciwie-Feit-Lerner were demolished. Even the house of the druggist Dr. Zacharski, who was killed by the Gestapo, was wiped out.

As I stood there I imagined seeing Reb Jakov Joel Wolker holding his bag of talit and “tefillin” (phylacteries) under his arm as he hurried to the “Beit Hamidrash” synagogue for prayers. In a moment I realized it was a hallucination for Reb Jakov Joel had found his place in the “brothers” grave and the “Beit Hamidrash” was completely destroyed.

As we approached the Rynek, a few remaining Jewish houses became visible - the house of the late Reb Chaim Jakov Katz, the house of Benzion Laufer and Reb Kalman Wolf. Opposite the house of Reb Chaim Zeiler were Reb Abraham Kornfeld's, Sima Kuflick's, Mendel Filer's (he died in Mexico) and Reb Gedalie Filer's; also the houses of the Laufer Family, David Jonah Markel, and Josef Pener which were still standing. All other Jewish houses were destroyed, replaced with new living quarters occupied by new and old Christian inhabitants.

The apartment in which we had lived was now occupied by our former landlord - Rychlik's daughter. At that time I avoided visiting my old apartment and decided to walk around the “shtetl” in order to find out some valuable information regarding the final moments when the pulse of Jewish life was still alive.

The weather, indeed, was not cooperative and it was difficult to take clear photographs of the “shtetl”. But from time to time the sun came out from behind the clouds and in those moments we took a few pictures.

At the end of the Rynek near the house which had been the late Dr. Samuel Selenfreund's office there stood a group of Polish people; one of them came near and remarked that he recognized me, but he could not remember my name. When I asked him to look on the other side of the Rynek and pointed out the location of our store, he cried out, “You are Mr. Chaim”. His name was Anton (his father used to fire the bricks in the late Ben Zion Trachman's kiln). Immediately other Polish people from Brzozow came near with the intention of having a “smuesh” (conversation). The first “shmuesher” remarked that he was ninety-two years old and did I remember him? As it turned out this particular person had been my teacher in the public school; his name was Niziolek.

[Page 139 - English]

I could spend no more time talking, for it was senseless to continue.

Next I decided to visit the apartment of Mrs. Kuzio, one who is among the “Chasideh Umot Haolam” (the pious among the gentile people). This tender noble woman had risked her life. She brought food for a few Jewish girls hiding in the forest of Brzozow until they were finally discovered by Polish informants. Mrs. Kuzio was now eighty-seven years old and lived together with her daughter. Our reception in their house was very emotional and many tears were shed. I received from them some information about the final days of the Jews from Brzozow and about the deplorable human behavior of a “part” of the Polish people.

We received additional information about the Polish physician, Dr. Szuba, who had been called to the hiding place in Mrs. Gorgacz's house of a sick person, Mrs. Henia Katz, widow of Reb Ha'im Jakov Katz; she was in desperate need of medical assistance. Dr. Szuba prescribed medication or the sick woman, but at the same time informed the Gestapo about the hiding place. The next day the Gestapo entered the place and took away Mrs. Katz, her daughter-in-law, Chaja Markel, her child, and arrested the Polish woman Mrs. Gorgacz. When I asked Mrs. Kuzio if this was a moral and ethical behavior of a physician, I received the diplomatic reply, “You could expect that kind of thing from him.” We will return later with a description of further information that I received from Mrs. Kuzio.

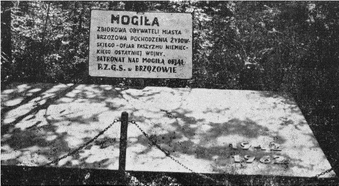

In order to reach “The Brothers' Grave” that day, we needed to rush because the grave was located in the forest. We rented a taxi and arrived at the destination - the grave of our “kdoshim”. It was difficult to find the exact location and we were forced to walk several hundred meters before finding the place camouflaged in the forest.

When I reached the grave, my whole body began shivering from my discovery. I found that grave partially desecrated, the metal plate containing the proper dedication in the Polish language was thrown down. Bones, skulls and skeletons were scattered all over the area, even whole skeletons peered from the deep holes made purposely for the grave. Apparently it was the work of Polish vandals scavenging for treasures of our “kdoshim” who had been resting there for over thirty-eight years. It is very difficult to describe the despair and rage of a Jew at that moment.

My son Bruno, flushed with tears, maintained his self-control and preserved that horrible scene on film.

I stood disturbed and for a moment felt as though my brain was covered by a mysterious cloud. In the silence surrounding us I heard the grass growing on the graveyard and suddenly heard a terrible outcry, “Why? For what reason did we deserve this horrible end?”

Arousing from my uncomfortable situation, I got no answer and could only conduct the prayer for the dead “El Malay Rahamim” (Almighty, full of compassion) and to ask “m'chilah” (forgiveness) for all survivors, “Landsleit” and for the entire Jewish population. Broken hearted from this painful experience, we left the brother grave of our “kdoshim” with a prayer that they would be the last victims of the Jewish nation.

I went, immediately, to the Municipal Council in Brzozow and informed them of the grave's deplorable condition and the imperative necessity for improvement. The secretary at the Municipal Council promised to send workmen immediately to remove the obstacles. He made this important remark: “We are very concerned that the grave with the remains of over one thousand martyrs, among them men, women, children and invalids, should remain as a monument of our sense of outrage with the German nation which reached the highest level of cruelty, comparable only to that of wild animals.” The answer was only con- The answer was impressive but hardly believable.

Our next visit was to our former housekeeper Aniela Raytar; there we received some information. According to her a young Jewish man named Klauser, from the town of Domaradz was a member of the Polish partisan resistance (The Native Polish Army - A.K.). Before the Soviet army's arrival he was snatched out by his Polish comrades. I was also told that on Liberation Day, the Jewish lawyer Israel Kuflik was seen on the streets of Brzozow but never seen him again. Solomon Mener, a Jew from Brzozow was hidden by a Polish family near the cemetery with the same result. No one knew what happened to him. Gita Fass was hidden by a Polish family, Bolek; she had been told that on the following day her house would be demolished. At the risk of her life she went to her house at night for her valuable possessions. Unfortunately, she was observed by a “Volksdeutch” (native German) named Kestling and turned over to the Gestapo. Herman (Hershele) Roth, leader of the “Agudah Israel” (The Society of Is-

[Page 140 - English]

rael) in Brzozow and family Hasidic man from the Rabbi of Czortkow, was hidden with part of his family by the mailman Skalski, who wiped out the entire family.

After leaving our housekeeper, we drove to Borkowka where the daughter of the couple Bargiel lives. Her mother let me know immediately after liberation in 1944, that my mother had left many valuables concealed and if I desired these things, they were at my disposal. I refused the offer since it was dangerous for a Jewish person to travel at that time in Poland. I now asked the daughter if she had any of the things which could serve as mementos. She crossed her heart and with tears in her eyes replied that nothing was left from her mother…When we began talking she told me that after the liquidation of the Jews from Brzozow, two sisters and a brother from the Birnbaum family, the Cheyder teacher Josef Aaron Birnbaum was their father, lived in a ruined house in Borkowka. According to the daughter's story, Mrs. Bargiel would throw a loaf of bread into the hiding place, until they were discovered one day and as a result of a Polish informant taken by the Gestapo.

It was very difficult for me to decide whether or not to enter the apartment in which I had lived. As I mentioned earlier, the apartment is now occupied by the landlord's daughter. Setting aside my unpleasant feelings in such emotional moments, strong desire and curiosity prevailed. I want to see and be present in the apartment in which we had lived for so many years and from which my dear mother, sister and brother were carried to their terrible destruction by the German murderers.

As we approached the house a woman was standing by the entrance waiting for the bell to be answered. We asked her if she was Mr. Rychlik's, the landlord, daughter. Her reply was, “Yes, I am Wanda, the younger daughter.” We identified ourselves by saying that we had been her father's tenants, but she did not recognize me, thinking that I belonged to the Reich family who had been our neighbours. When I began to explain that her father also had second tenants she embraced me and started to cry, “Now I know! You are Mister Chaim, son of the noble Mrs. Masia.”

At that moment the door opened and she introduced me to her older sister, Maria with her husband, the current owners of our apartment. After the customary greetings and an invitation to come into “their” house, we sat down and had the regulatory glass of vodka offered by Poles to drink “Le chaim” (to life). Then we started with the “shmues”. Meanwhile my mind was trying to absorb the completely different feeling of the place and I was not in a mood for conversation. Apparently noticing the change, in me, the hostess turned to me and said, “Of course I understand your feelings at the moment, and I will leave you alone for the time being.” After a few minutes she returned and asked me to go through the entire apartment to convince me that no physical changes had been made. I gladly took the initiative and without disturbing anything walked from room to room noting that everything remained the same except the furnishings.

As I walked through the rooms, I stopped by the window that looked into the backyard where there had been the living quarters of many Jewish families. There were no more Jewish homes with their inhabitants, but in my imagination I heard Reb David Lapin the “shochet” with his strong baritone repeating the prayers for the High Holidays (Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur), those sweet words “Vehavienoh Lezion Irchah Berinah… Vesham…” (Lead us in triumph unto Zion the City… with song… and there…). At that moment I returned to reality and realized that it was an illusion, a mirage in the desert. Everything in the backyard was changed; there was no sign whatsoever that our “hejmish” Jewish people once lived there.

After a light snack we continued our conversation; we asked each other questions regarding family and general characteristics. Before leaving the apartment our hostess handed to me a brass candlestick covered with dust and ends of unfinished Sabbath candles and also a Hanukah menorah in which my Grandfather had lit the Hanukah light which consisted of cotton wicks dipped into oil.

I received, as well, a pamphlet written in Polish, entitled “The History of the Jews in Poland” by Naftali Shipper, (not related to Dr. Ignatz Shipper). While giving me the “gifts” the hostess explained that she had discovered these items in the loft under the roof of the house. She promised to look again to see if she could find other substantial things which might be of value to me. With a farewell I left and we promised to be in touch with each other.

Once more we walked around the “shtetl” to complete our view of the changes and replacements that had taken place since the destruction of the

[Page 141 - English]

Jewish population. I finally determined the following facts:

The fact also came to our attention that after the war Josef (Joske) Tag the son of Zudek Tag was murdered on the railroad station in Rymanow and carried out by the Polanski brothers from Bzianki. They used to bring passengers from Brzozow to Rymanow in their automobile. (Reb Elimelech Herzlich the “kadosh” was murdered by his Polish neighbor, Michal Yayko, who pretended to agree to hide him, and in this way inherited his possessions.) I received the names of various Polish informers who sent Jews in to the hands of the Gestapo. All the Poles as well as the “Volksdeutch” (native German) escaped punishment together with the Germans.

I intended to visit Mrs. Zacharski the widow of Dr. Zacharski, who as mentioned before, was killed by the Gestapo. After my liberation in 1944, Mrs. Zacharski sent me a letter offering unlimited financial assistance, to give me an opportunity to get back on my feet. At that particular time I was unable to benefit from her generosity because I had left Poland for another destination. At the present time Mrs. Zacharski resides in Jaroslaw and as a result it was impossible to see her in person.

A museum with various exhibits, most of them Jewish, was established in the Town Hall of Brzozow, but regrettably it was closed at the time of my visit.

We reached the moment for departure and so started the “Vaichad Yitro” (dilemma); on the one hand I desired to leave the arena called “Brzozow” as quickly as possible, on the other hand, it was difficult to depart from the place to which I was connected by so many memories - pleasant and unpleasant. My heart is in the “shtetl”. My eyes were full of visions; I was still seeing my fellow Jews in their everyday problems, successes, delights and sorrows. I saw and listened to the souls being summoned in vain as they rose from their graves, bidding farewell, and proclaiming to me, to all “Landsleit” and to the entire Jewish people, that such outrageous experiences should never be permitted to repeat themselves.

It only remains to me to ask them “mchilah” (forgiveness) from “our brothers who sacrificed their lives for the sanctification of the honor of Israel. And may the purity of their souls be reflected in our lives.” We pray of a better future without such painful and heart rending suffering…

We left Brzozow by bus for Przemysl. On the way we stopped in the town Dynow for a half an hour. In that short time I looked around the shtetl observing only very small changes. A few houses and stores which had belonged to Jews were empty. Here I was informed of a Jewish hero, a “kadosh” named Hoch (I don't remember his first name). During the extermination of the Jews in Dynow, Mr. Hoch jumped on a Gestapo man and killed him instantly; he was, however, killed on the spot by

[Page 142 - English]

machine gun bullets. We also passed through several other Jewish villages including Dubiecko and Krzywcza.

Finally we arrived at Przemysl and went straight to the place where the ghetto had been. It was here I had my own sad experience during the decline of the ghetto. Not far from the ghetto, we visited the house in which we had been hidden by a Ukrainian man, after escaping from the ghetto. Sixteen men and women were hidden there as well as my son Bruno, who at the time was four years old. He was the only child there. We also visited the street where my in-laws, Mr. and Mrs. Abraham and Ziporah Sperling had lived.

We left Przemysl by express train for a one day trip to Zakopane, located in the Karpat hills in order to recuperate there. It was delightful; the landscape was beautiful, and I indulged myself by thinking that the Polish people did not deserve such a natural treasure.

From Zakopane we were forced to come back to Warsaw; passing by cities like Kielce, my blood began to boil in my body as I remembered the terrible pogrom in 1946, in which the Poles cut down defenseless Jews - men, women, children and even pregnant women. A total of forty-two were killed by our “brother citizens”. It seems to me that the Polish people intentionally wanted to finish the plan of the Germans, by murdering the Jewish survivors of the concentration camps, as well as refugees from the Soviet Union.

Not far from Warsaw we passed the town of Gora Kalwaria, which once was full of Jewish life and intense religious spirit. It was the center of the “Gerer” Hasidic movement, a group with a Hassidic population approaching the tens thousands, perhaps even hundreds of thousands.

Before departing from Poland I was in a state of confusion, resulting from the realization that no long ago three million, five hundred thousand Jews had lived in this Polish territory. At present there remain five to six thousand Jews, old and sick people. Fear possessed me, body and soul. My lips whispered quietly, “The soil of Polish land deserves to be cursed because it is saturated with Jewish blood.”

A mystical divine hand had guided me to my “shtetl Brzozow, turning me into a witness in order to meet the challenge of restoring and improving the condition of the “kdoshim brother grave” damaged by ferocious vandals.

I am sitting now in an airplane which will take me via Switzerland to our Eretz Israel. Behind me was a land of deep-rooted hatred for the Jews and that soil soaked with innocent Jewish blood.

I now have a great deal of time to think. My brain is bursting with all kinds of thoughts about the suffering and pain I have recently experienced with my own eyes.

I am saturated with tragic war-time experiences from which keep coming to my mind. I keep thinking and am not able to come to any conclusion. It is frightening to relive all of that once more, even in your mind. I keep coming up with the same result: We Jews are encircled by wild animals desiring to swallow their victims. Yesterday it was the German murderers with their sophisticated “culture” which was supposed to win the world. Now the names have changed to the P.L.O., or peace speakers, followers of Stalin, with their slogans based on the “liberation of the world” a euphemism which goes together with hatred for the Jews. In our America obscure individuals are also rising up against us mouthing their well-known philosophy of the Nazis…

And now the “Bechol Dor Vdor Omdim Aleynu Lechaloteynu” has become a part of our lives. This idea is always prevalent among the nations and we must constantly be on guard against it.

All the philosophers, spiritual leaders, statesmen, politicians, persons of high culture and educators, etc., claim the improvement of mankind's condition to be their main principle. But man has been stripped his sensitivity towards events of individual catastrophes which have led to twentieth century to a shambles - reverting Sodom and Gomorrah.

But what will all this investigation bring?

Thank God, I have landed at Lod airport and with Israeli air once more in my lungs, my mood has changed completely. All troubles disappear as with a magic wand. The sense of power one has in one's own land is rejuvenating and disperses my sense of inadequacy.

Here in my Jewish homeland the instrument of our future survival, I am filled with self-exaltation, renewed vitality and pride, and a sense of a future for our troubled people. Here I feel that “Lo Alman Israel” (Israel is not left behind) and I see the “Am Israel Chaj” (revival of the people of Israel). My lips whisper a prayer to the Almighty that this should last forever more AMEN!

[Page 143 - English]

by Sol Filler

(Published in “The New Zealand Herald Weekend, by Helen Davis) - April 24, 1976)

April 27 is the day when Jews throughout the world remember and mourn the six million Jews murdered in the Nazi holocaust.

It is a day of poignant memories for Sol FILLER of St. Heliers Auckland. He spent more than three years in Auschwitz concentration camp where four million Jews were killed.

Last year he and his wife, Ruth returned to Poland to visit Auschwitz and the Galician village of his childhood.

“I was warned in Israel not to return to my village,” says Mr. Filler. Two Jews who did return there after the war were killed because they tried to reclaim their property. Polish Jews I met in Israel thought I was mad to go back.

But I had to go. I was compelled to say Kaddish at my parents' grave.

Ruth and I hired a car in Krakow and drove to the outskirts of my little village. We found the monument to the Jews who were murdered there. But we couldn't find the grave itself. Eventually we met a nun from an orphanage at the forest's edge.

I explained to her in Polish who I was and what I was looking for. She took us deep into the forest to the place where it happened.

She told us how the Jews had come in trucks - about 1000 men, women and children - my parents and two brothers among them. They were forced to undress at the edge of the forest. Then they were marched to a huge pit and shot. They were covered with lime and buried.

I asked her how she knew all this. She told me that boys from the orphanage had climbed up into the trees and watched it all.

We went into the town to have a look around and to buy some postcards. I introduced myself to the postman. And he knew immediately who I was. “You are Gedalia and Ruth's son,” he said. He was amazed that I had survived. He took me to see the baker who had worked for my father. They were very moved to find me alive. So few had returned.

I'd have stayed a little longer, but Ruth was very frightened. Especially when the postman started asking me if I had come back in order to sell my family home. I said no, forget it. I don't want the money.

I left with my wish fulfilled, leaving as a free man and not under guard as I had been taken away the last time - six days before they rounded up all Jews and shot them.

But I had to go back to Auschwitz. Almost every night I dreamt that I was back in camp being beaten by the guards. And now the dreams stopped.

I saw it empty. No guards, no Germans, no prisoners. I walked in and I walked out again. Free to return to New Zealand. I'm pleased I went. But I wouldn't want to go back again.

Mr. Filler was 20 years old when he was taken from his village with his 15-year old brother Ben. The Germans put them to work in a camp near Cracov, building a railway.

The brothers escaped into the Krakow ghetto but was recaptured and taken to Auschwitz when the ghetto was demolished.

Among 25,000 Jews were transported in that shipment to Auschwitz, where the notorious Dr. Mengele “selected” 500 Jews. The rest went straight to the gas chambers.

We had to run about 200 meters past soldiers who were hitting us with their rifles, says Mr. Filler. “If you started to bleed, you went to the chambers - although of course we didn't know that at the time.

I got to Mengele with Ben beside me. “How old” he said. Twenty. Occupation? Baker. And he waved us to one side, which meant we lived.

But of those 500 selected, only 200 survived the first four weeks in quarantine, when we did all sorts of jobs until the Germans found permanent work for us.

The prisoners died of typhus and dysentery contracted after drinking contaminated water. Others were kicked and beaten to death. We had very little food. In the end maybe 10 people survived from that whole Cracow shipment. I personally know of only

[Page 144 - English]

there including Ben and myself. Perhaps there were more.

I survived because I was young and fit and because I was determined to live to take my revenge on the Germans after the war. Not everyone had that determination to survive. A lot just gave up and killed themselves on the electric fences.

I quickly found out that you get used to death. We were put to work loading corpses on to trolleys and taking them to the crematoriums. After a while you lift up legs and arms as if they were nothing.

I was sent to work in the coal mines. We got up at 4 in the morning, started work at 6, after a long walk and finished at 10 or 11 at night. All we had to eat was a bowl of soup and a bit of black bread. At night we took our uniforms off and folded them up as pillows.

We were slaves. It was almost unendurable. I saw boys deliberately injure themselves - cut their own hands and fingers off in the mine machinery so that they could go to the hospital. We all know that no one ever returned from the hospital, but that didn't stop them. They just wanted to finish it.

The men we all feared the most were the kapos, the prison guards. Auschwitz was run by German underworld types. Murderers and criminals. They were the kapos.

The kapos could do whatever they liked. They killed indiscriminately and the Germans didn't care. We had roll call twice a day. If the roll said there were 180 men in the barracks the SS didn't care if 20 or 30 of those men were lying dead on the barracks floor. So long as the tally was right.

On January 18, 1945 Auschwitz was evacuated. The Russians were drawing near and the SS marched the Jews for five months, in the middle of winter, with virtually no food and no clothing other than their cotton uniforms.

About 30,000 prisoners left Auschwitz. Only about 200 arrived at Theresienstadt in Czechoslovakia. When men couldn't walk any more, they were shot. It was hell. Mr. Filler suffered more on that march than in his whole three years camp. For the first time he had doubts that he would survive.

“I escaped several times, but I was always caught again,” says Mr. Filler. “I didn't try to escape from Auschwitz for the simple reason that there was no-where to go, no one who would hide me. I was told that he Partisans hated the Jews as much as the Nazis, and killed any Jew who tried to join them.

The only people who showed us any kindness on the march were the Czechs. The villagers would come and throw us food - bread and apples mostly. We were very grateful for that food.”

“We were finally liberated from the ghetto in Theresienstadt. At six one morning we heard a rumbling and there was a motorbike and two tanks of Russians. We rushed to get out of the barracks, but the Czech police wouldn't let us go.

I approached the commander of the Russian group that liberated us and tried to explain in Russian what was happening. He said to me in Yiddish: Don't break your teeth on Russian. Speak your mother tongue.” He was a Jew.

He told the police to let us go. We were like madmen. We must have looked very frightening. Leaping, shouting, haggard skeletons.

A lot of boys died because they over-ate in those first few days of freedom. They ate butter by the handful and anything else they could find. And their systems couldn't cope. They got dysentery and died. It was terrible.

Others had nervous breakdowns - men I thought were as tough as nails who could take anything in camp. But one the war was all over it hit them. All their families, their homes, everything gone…

I don't believe it could happen again. I think the Jews are different since the holocaust. We have ISRAEL behind us. We've learned a lesson.

The Jews of Europe were too gentle, too helpless. And not just the Jews. Everyone seemed to lose their will to fight back.

I remember, early in the war, when the Germans had taken over my little village, being summoned to the police station to chop wood and wash floors.

A German soldier asked if I could speak Russian and I said that I could. “Then tell these Russians that they are going to die,” he said, pointing to the three Russian prisoners, sitting on a bench outside the station.

I hesitated. It is a terrible thing to have to tell a man that he is going to be shot. But the German made me do it. I said: Look I am terribly sorry, but the Germans are going to kill you. They just sat there and said nothing. One shrugged.

They were strong young men, trained to defend themselves. They weren't even under a very strong guard. You'd think they would rather die fighting than die like animals. But they did nothing. They were loaded on to a cart, taken to the forest and shot. I helped to fill the grave.

[Page 145 - English]

by Zippora Levite (nee Hager)

|

|

I was neither born in Brzozow nor ever visited it, yet somehow I feel as if I were a native of that town, have lived there for many years and was deeply involved in all its affairs.

After I married a native of Brzozow I found myself adopted by the few existing survivors who made me a part of their family.

As I had wandered a lot in my childhood, which was spent mostly in a large city and its environs, no place meant very much to me and I was not familiar with the tightly-knit, intimate relations of shtetl inhabitants in general and those of Brzozow whom I now got to know.

For the last three years “Brzozow” has been a constant presence in our home, becoming an integral part of my being so that I feel that it has also absorbed me into it. But alas for such an absorption! Would it have been otherwise!

I can imagine myself strolling among its highways and byways, knowing just how to maneuver the descent at the Beit-medresh Barg without barging into the opposite wall before the turn. I feel I could find my way to the “Schochet” beside the “Bedel-wasser” stream, and it is no secret to me where to find the children and the youngsters playing in the “untern barg”. I could even name the people praying at the “Beit-hamidrash” and those at the Clois; who attended high school and who remained solitary, candle in hand, studying the Gemarrah at the Beit-hamidrash. Yet my imagination balks when it comes to the way leading to my husband's family, to his father's house. How am I to reach his mother's home and make her rejoice at the sight opf my growing children, my grandchildren…? Where can I find his brother, he who remains eternally young and whose name my grandson bears? And how can I ever reach my brave and beautiful sisters-in-law? Are they in the forest? A childhood rhyme rings in my mind: “In wald hob'ch moyreh!” (I am afraid in the forest…)

It is a terrible sense of naked, quivering bereavement, this total absence of at least a tombstone that one can touch and feel a contact with those buried beneath it. It is this total deprivation that creates the longing for everything that is evocative of the shtetl.

Personally I knew very little about the Jewish Gallician shtetl and its inhabitants. I have a vague and very early memory of a street scene in some East Gallician town - a mud-covered street with wooden boards (“kliatkes”) lying across it, the Jews walking on them looking sad, for some reason. Any later knowledge I may have had comes from the books I have read.

It appears that there was a weekly market-day in Brzozow and thee were those who subsisted throughout the week on the earnings made on that single day. Yet, they were the people who never had enough money to lay in an adequate stock. From one person's tales, from the memoirs of another and the evidence of a third I can recreate in my imagination the Brzozowian “institution” of “short-term loans” - Gemilath Hessed. With the money lent by one person another buys and sells, pays back and so on, ad infinitum. “Azov ta'azoz imo” here assumes a special meaning and reality. Then there was another “institution” - the nightly watch kept by two youngsters at the bedside of a dying man -- “nech-tiken”, to enable the exhausted family to get some rest before coming back to tend the patient on the morrow…

[Page 146 - English]

Modes of living evolved over the generations, where have they gone, erased as if they had never been?

I was there when the idea of the book was evolved, witnessed its progress and perused its pages as they piled up. I listened to conversations about the shtetl and its people and saw the labor of collecting and joining the shards of broken memories culminating in the work of reconstruction. It has been a labor of love and devotion.

During all that time I suffered many a nightmare and fearful dreams. Having identified myself so completely with the subject, I am no longer objective about it. But it seems to me that when we read these pages the picture rises up before us of a Jewish shtetl in the diaspora, active and full of life, which has sunk into the depths… This is an attempt to preserve its shadow from complete oblivion and thus, perhaps, put up a modest monument upon the graves of those who have been denied a resting place.

At moments of sadness and longing we, our children and grandchildren, will be able to take this Memorial Book from the shelf and, as we leaf through it, see ourselves as if we were going up to the graves of our Fathers (“Kever Avot”) to be at one with the memory of all our loved ones whose lives were cut down before their time.

|

|

the path leading to the scene of the annihilation. It was built by the Polish authorities in 1962. |

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Brzozow, Poland

Brzozow, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2024 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 29 Jul 2013 by JH