|

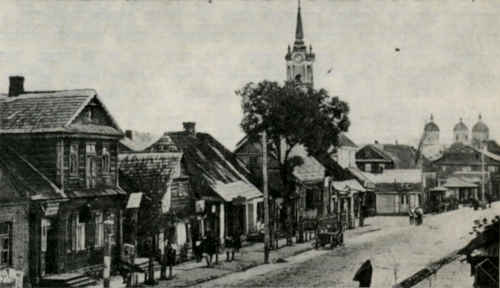

Bielsk – General Appearance

|

|

[Page 59]

by Bracha Zefira[1]

Translated by Nancy Schoenburg

In 1930 I visited Bielsk on my tour in Poland, and to this day it is etched in my memory as a unique city. The impression it made on me cannot be erased.

I was at that time a 15-16 year old student at Max Reinhardt's Institute of Theatre and Music in Berlin. As an orphan from infancy and independent in my decisions, I reacted to the impressions as an adult in every respect. As it is now, so it was then, that people from The Land of Israel would travel outside of the country, going, looking for a rest from the tension of pioneering and the intensity of life in The Land, assembling and sticking together with each other at gathering points just for them in the place where they landed.

In Berlin there was a community center where we would assemble and yearn together for our country and for our pure names. And here one evening a peppery Jew approached me, one of the immigrants from Romania. His name was Shafan.[2] He had just returned from an appearance tour that was arranged for Jabotinsky, and after that for Bialek in Europe. He tried to convince me to appear in Europe under his promotion. He convinced Nachum Nardi[3] and that influenced me, and I left.

That is how I ended up in Bielsk as well.

From the beginning it was understood that Shafan arranged appearances for me and for Nardi in the capital city Warsaw, my performance being in the Conservatory. There I met Isa Kremer[4] and Rina Nikova[5] and other prominent theater people in the Jewish world. It can be assumed that Warsaw was astounding. It aroused excited admiration and made an impression and so forth. In any event, my heart remained frozen to her [Warsaw] and she impressed me very poorly, except for one incident which stirred in me great excitement. The agitation, which expanded and grew to mystical proportions, was in the face of the Shoah [Holocaust], of which the Book of Bielsk is also tragic fruit. At this event I had a chance meeting with Elchanan Zeitlin, son of the great Hillel Zeitlan.[6] I myself sang at that time what I breathed and my soul had absorbed in the awakened [Land of] Israel. This I brought in sound and in vision to the listening audience in the diaspora. I sang “Yafim HaLailot” [“Beautiful Are the Nights”] and “Mi Yivne Bayit” [“Who Will Build a House”]; from the popular poems of Bialik and songs of the mizrach [East; oriental, especially Yemenite] that were part of my soul and my spirit. The younger Zeitlin approached me. He wanted to say something but could not manage it. He was too emotionally moved by this literary and musical greeting that I brought them from the land of the azure skies. As a profound Hebrew poet, his interest in it was deepened. He tried to express this but was not able. Over the years, with the ending of the Shoah, one of the survivors of the Warsaw Ghetto told me that during their days inside the ghetto there was no song and no poetry. The late Zeitlin z”l wrote a poem that everyone was longing for our small homeland, and above the lines of that poem was a dedication blessing to Bracha Zefira, who “On her visit to Warsaw showered me with dew of longing and vision and brought with her the taste of the homeland. The singing motherland and the awakening nation.”

That is everything connected to my visit in Warsaw. It remained a routine visit and were it not for this retroactive memory, it is likely that it would also be reverberating to the depths of things to be forgotten because it was created to be forgotten.

After Warsaw we came to smokey and smoggy Lodz with its dry Judaism sealed off from poetry and other spiritual affairs. Buttoned-up Bialystok, all of which was hidden and was not in the shadow

[Page 60]

of its Hebrew gymnasia. The impression that this school made on me was so strong that it alone remained with me as a memory of that city.

In general this tour in Poland was one with great depression in it, with gloomy cities whose inhabitants were gloomy with dejected souls, cities whose outward appearance was grey, matching their sad Jews, depressed to dust with nothing in themselves to hold onto.

|

|

Bielsk – General Appearance |

I remember silent Vilkovisk, suddenly waking up from its stillness on market day where everyone is selling horses and trading with each other. The next day in Branovich [in western Belarus], a mother-city in a district with houses too small for its size; houses that are really tiny and its residents stoop and enter their gates, but it is all a company of singing and joyful music. Its streets are humming from groups that were born to sing. Nevertheless, it was a gloomy city.

And Grodno of Cherno[7] dared to establish a seminary for teachers and kindergarten teachers in foreign lands and to establish kederim[8] for teaching biblical studies and the language from the past [Hebrew]. And the impression was strong. Really strong. That was the impression of this seminary.

But all these passing impressions are joined with one general impression of cities and towns that are all dreary, and there is nothing to gladden the heart of a singer, still a child, whose soul is open to something new and different and surprising, and that is not in them.

Until I came to Bielsk.

Suddenly it was like I fell onto a different planet. After the dirt roads in the Jewish towns of Poland and their dusty houses with vestiges of a rainy winter and an autumn that casts its drops of mud on everything that it happens upon on its street. I suddenly found here an amazingly clean city. Its streets are polished, and its homes are white with their cleanliness. And every window in them with thousands of suns reflected in their shiny windowpanes, whose curtains flutter with much charm and are ironed and proud to receive, as it were, an important guest from the Holy Land.

[Page 61]

The entire way to the place where I was staying in Bielsk seemed to me like a bright path leading to the festival and sacred attribute. There was something about the streets of Bielsk, which was not in any other city which I had previously visited. Everything here was white and clean. Sometimes it seemed to me that all of Bielsk was a city of pampered people, who even in their poverty could not stand dirt, gloom and dreariness. It was as if they were always occupied with polishing their city and cleaning their courtyards and the alleyways of their neighborhood.

I remember how difficult it was for me to endure the feeling of sadness that enveloped me when I would enter a Jewish city in Poland and when I would leave it. At the entrance before the action of their markets, I felt a full spasm of despair for the Jews chasing after a livelihood and being disappointed. The dark alleyways filled me with depression and disgust, and it all grew stronger as I left there. The children followed me with their eyes through the car window, their eyes mysterious and yearning for something far away and hidden which was forbidden to them, as it were, by the dictates of their fate. In those towns, standing before my eyes was the spirit of my little Tel Aviv, with its azure sky. The joy of its whitened streets and the singing of merry children and my heart was enwrapped and pulling me away from here.

Not so Bielsk: here it was as if I returned to one of the quarters of a clean, German town, as all were then, with a culture of cleanliness and order.

I recall my entering into the auditorium in Bielsk. The chairs sparkled from lacquer that the people of Bielsk remembered to rub them with for each event that seemed to them honorable and special. The floor was scrubbed and polished, the walls glistened with their clarity, and the space was filled with silence. A festive quiet of the expectation of something big that was about to happen. In a little while the stillness would be pushed outside, and in its place would be a symphony of sounds and voices, all waiting with impatience.

That is the impression I got of the auditorium in Bielsk, where the people of Bielsk were imbued with the joyous spirit of the occasion.

If every place in Poland and in Israel where I performed my songs and illustrated their contents with facial expressions and motion, as is proper with folk songs, then here in Bielsk a different spirit was in me. In light of the celebration that poured out into every corner here and on every face, I also was filled with that festivity. I cleaned myself up and I got myself ready, not just for singing, but for a concert. The evening in Bielsk was truly a concert with the audience dressed for a holiday. They were polished, clean and tense. I also stood there tense, serious, without the movements and grimaces; the back was not bent nor were my eyes winking as I would have had them accompanying my folk songs. Here I stood, tense, listening to myself, meticulous in every note, every variety of melody delivered here in trustworthiness for the concert, for the celebratory audience at this concert.

And if I ever wanted to clarify it for myself, upon turning the pages of my travel diary - where did this relationship to Bielsk come to me from and why was I impressed thusly. I explain it to myself that this is something that I call culture of man. In Bielsk they had a tradition of culture that made it forbidden to desecrate with a lack of culture, that is to say, if people get together for different occasions, everyone must leave their personal weaknesses and must all be attentive to the general wishes of those gathered. They must not be a burden on other people or on the “performer” in listening. Everyone must contribute a personal contribution with self-control and silence for the sake of the general quiet.

[Page 62]

Because we are not speaking here about a passing thing; here is about to take place the culture itself to add a link to the chain of the advancement of man. First of all, it is a culture of silence and sound, of attentiveness and a celebration raising the spirit.

All this explanation came to me from the festive impression I got in Bielsk during my first contact with her. I received its approval afterward, after my concert. When I finished my program and hinted to the Bielsk community that the program was over, an amazing, powerful song broke out in the hall. There was total enthusiasm of the audience in its entirety. I have only seen such a thing a very few times in my life and only in my country. But first I tended to think that all the silence that accompanied my appearance in Bielsk, beforehand and during it was a kind of an expression of coldness of character and lack of enthusiasm. But after this burst of passion following the concert, it was clear proof that the people of Bielsk were blessed with self-restraint and with great spiritual concentration. When something is spoken related to the art of singing, the intelligence of attentiveness is the right definition that was shared by all the people of Bielsk, the kind of listening that has in it a deep expression of their spiritual aspirations and transcendence. The wonderful people of Bielsk.

And especially the youth, the wonderful youth of Bielsk.

In most of the towns on my tour, as mentioned, there was a sadness extending from every event. Everything was carried out by adults, while the youth were serving as messengers and doing what they were told. The gloomy indifference that the adults were not always able to overcome at the time of the program and that almost infected the youth as well. But in Bielsk everything was different. The youth were seen in everything, and I would almost say that the young people were in control of everything that happened around me. The adults would listen to them and would behave accordingly for a festive event where the people were assembled. And this also is a measure of culture of a high nation, a mutual obedience of generations, of fathers and sons.

The young people of Bielsk were truthfully something rare in Poland. They all had smiles, joy, a sense of duty. They were enthusiastic yet restrained. They were heard without voices, understood and profoundly important, without an after-taste of despair and helplessness which usually accompanies people of thought. This was an elegant youth, fine and likable and unable to be forgotten.

All that evening I felt the excitement in the activity of the youth. I saw that these young people were literally jumping out of their skin, to do things, to add something, and to break out and run. Despite that, there was some kind of discipline that was invisible but very much felt as when one person obeys another. And the activity is done according to the wishes and satisfaction of everyone.

I write down words in art, and my regard for Bielsk is of course as the regard of an artist for his listening audience. But not only as an artist; I was also filled with enthusiasm and affection for Bielsk as a young Jew, a native of The Land [of Israel], absorbing the culture of the nations and human beings on her tour. I saw in this city many special and superb things.

As an artist I was not able to escape from the discovery of the high folk-education that the people of Bielsk had absorbed from some source unknown to me that was revealed to me that same evening of the performance. I saw before my eyes an audience that knew the tradition of a concert and of song to create a framework for success. The doors were closed on time, with the entire audience already seated in the hall; no one was late. The opening time was held to the exact moment, and intermission took place at the appointed time and no one

[Page 63]

burst in toward the artists, neither to Nahum Nardi[9] nor to me to disturb us. They knew that this recess was designated for us to rest and to be together, to let go and to focus. They did not have permission to disturb us. Behind the scenes, we heard a noise of the assemblage during the intermission. We were surprised to see the audience all sitting quietly in their places when we entered the hall.

Where can such an audience be found today? And where was it then?

A wonderful city of Bielsk remains in my memory, and it is difficult for me to forget her. The hardest to forget is the marvelous youth that was there. I am reminded of the excitement of these young people standing there to receive our autographs, expressing their yearning for The Land [of Israel], its artists, and the culture that it was forming. Their eyes sparkled with hope, that soon, in just a little while, they also would be participants in creating the wonderful nation. It hurts me deeply that they were not given this opportunity. And the pain is very great.

Translator's footnotes

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Bielsk-Podlaski, Poland

Bielsk-Podlaski, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2024 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 22 Dec 2023 by JH