|

|

|

[Page 371]

[Page 372]

|

|

|

|

[Page 373]

The German-Polish War

by Elchanan Sarvianski

|

A short time before the outbreak of the war, the Poles felt that it was approaching with giant steps. The newspapers wrote much about the “Prozdor” (Danzig, the free port city), and informed that the Germans were drafting an army and stationing it around the Prussian border, Pomerania, and Upper Silesia. In Augustow they already felt that something was about to happen. In those weeks it was possible to see that the Polish government began to implement means of self-defense after it came to know that it had been deceived by the Germans, and the Beck-Ribbentrop Agreement[1] did not help it. The Suwalki foot brigade abandoned Suwalk, and reached Augustow in the night. It crossed Bridge Street (Brik-Gasse), entered the market (Plotz Pulsodskiago), and to Krakovska Street. From there, I do not know – if to the Osowiec Fort, or to Grodno.

The police, fire-fighters, and the other types of “patriots” occupied the produce warehouses of the Levit brothers, and directed the produce of the area there and to the other warehouses that had been nationalized.

They began to catch people from the houses and the streets, for the digging of positions. The people hid. They went, therefore, from house to house and searched for men. I was curious and I went out to the balcony (an open veranda). They immediately sensed me. I fled to the upper roof of our house and I hid behind the chimney. They caught me, took me outside, and transported me together with a few other men to the excavations. The custom was: if you finished digging your quota, they freed to you to go home. On the way they caught you, and – back to the excavations. Tens evaded this, as usual, with the help of a bribe.

The excavations were dug in three separate places. At first, they dug simple military posts for the foot soldiers on the way to Ratzk, 5 kilometers from Augustow, next to two windmills, in a place

[Page 374]

that was called Slepsk. This was, apparently, the first line against the invasion from Prussia, by way of Gabrova or Ratzk. The second line was next to the train station, not far from the sawmill and the “Lipavitz” electric station. The third line was on the way to Grodno, on the 5th-6tthkilometer on the deep Sajno River.

Friday, September 1, 1939, was a market day (there were two market days every week in Augustow, on Tuesdays and Fridays). I arose at 4:00 in the morning and I walked to the Grayevo-Grodno crossroads. This was the place to which the small Augustow merchants would come out to meet the farmers' wagons, laden with various merchandise. Suddenly a tremendous noise of airplanes was heard. Hundreds passed over us. They came from Prussia. At the hour of 7:00 in the morning, approximately, all the residents of Augustow already knew that war had broken out. The Germans attacked Poland without advance notice. Meanwhile it became clear that the squadron of airplanes that passed over us had already shelled Grodno and Warsaw. On their return, they flew so low that I worried that they would destroy the chimneys of our houses with their wheels. A few of them bombed the train station, which was full of soldiers preparing to travel to Grodno. They were killed. That same hour information was received that in Garbova the Poles struck a German plane with a machine gun. The plane crashed, but two German pilots escaped from it. I remember that they brought them, slain, to the Polish hospital on “Posbiontny” Street, and all Augustow, the Poles and the Jews, went to see slain German pilots.

On the second day of the war there was announced a partial army induction; there were not enough arms for a general induction. A few names remain in my memories: Tuvia Brizman, who went and did not return; Feivel Lazovitzki did not return; Yaakov Blacharski returned and was killed in the Shoah; Berkovitz (Tzirski) was seriously wounded in Grodno; Lieske Gutman returned and was killed in the Shoah. The men wanted to fight, requested to enlist, and were answered negatively. Time went by quickly, and the Germans did not conquer Augustow, they preferred to go by way of Grayevo and conquer the “Osowiec” fort, and from there to go up against Warsaw. In this way Warsaw was left without rule.

At that same time I completed 20 years. My parents were afraid that if the Germans entered they would kill all the men of army age. They began to pressure me, that I should flee with the Polish army and not fall into the hands of the Germans. I did not want to listen to them, since my father was sick. They decided, therefore, to act behind my back and spoke with Hillel Rotenberg, the brother-in-law of Abba Popkin. He came to me, spoke with me, and convinced me to flee. This was on Friday, exactly a week after the outbreak of the war. On the Shabbat day, September 9, 1939, I came to Hillel Rotenberg. In his yard there already stood four wagons, each with a wagon hitched to a team of horses. We loaded various merchandise onto the wagons, and turned to the road that went to Suchovola. From there we wanted to continue to Bialystok.

We left Augustow with broken hearts. We crossed the bridge, and travelled and travelled in the direction of Bialobrega. Before Bialobrega we met a small group of 4-5 Augustovian Jews, and at their head the old Rabbi Reb Azriel Koshelevski, may the memory of the righteous be for a blessing. We requested of the Rabbi that he come on the wagon, but he refused. Towards evening we reached Suchovola. We spent the night there and regained our strength. On the next day towards morning we moved our caravan in the direction of Korotzin-Yasinovka. The Rabbi and the Jews from Augustow that accompanied him remained in Suchovola. We passed Koritzin, Yasinovka, and reached the Knishin forests. Suddenly soldiers and Polish officers emerged from the forest, and asked where we were coming from. We told them that we were from Augustow, and fleeing from fear of the Germans.

[Page 375]

They were so confused that we really took pity on them. On the next day before noon we reached Bialystok in peace. We unloaded the merchandise by Hillel Rotenberg's sister, rested a little, and went out to buy a few casks of oil. Hillel had enough money for his needs. We came to the factory, and there they informed us that they were no longer selling. But, since Rotenberg was a customer of theirs for years, they took it into consideration and sold him one cask. We tried to buy as much as possible, but they were not selling for Polish money. The economic situation got worse. It was impossible to buy any needed food for money, but only in barter, that is to say, for salt, kerosene, matches and soap. We did not have that merchandise. We were a little hungry, however, even though we had money. A day or two after our arrival was Rosh HaShanah.

On Rosh HaShanah eve the Germans bombed the storehouses at the Pulaski train station. When the Poles saw that the Germans were getting close to Bialystok, they opened the storehouses, and called to the public to take as much as they wanted, only that the goods should not fall into the hands of the “Swabians.”[2] I too ran there, and took as much as I could carry. On the way back, the German planes came and began to bomb. A few people were killed. I was saved by a miracle but I lost part of my booty. Meanwhile the neighbors came and told that on Staroviarsk Street they opened the storehouses of tobacco and cigarettes and everyone could take as much as they desired, so I also went there and brought tobacco and cigarettes. On the next day on Rosh HaShanah in the morning, we went to pray by one neighbor who had gathered a minyan in his house. Before the Torah reading, the son of one of the worshippers came and called: “Jews, in this moment the Germans are entering the city.” We stopped praying, and we scattered, each one to their house. We shut the gate and the shutters, and did not go outside.

On the next day, the hunger began to bother us. Neighbors told that on a Polish street they would distribute bread, one kilogram to everyone who would stand on line in front of the bakery. When my turn arrived the bread was gone. On the next day, I stationed myself on the line at 2:00 in the morning. A great many people were there. The Germans kept order. This time I was able to get a kilogram of bread. It was like clay, and without salt. But, since we were hungry, we swallowed it. I got used to going outside. I would take tobacco in my pockets, a bottle of oil or vodka, in order to trade for foodstuffs. Sometimes I succeeded, and sometimes, not. Yom Kippur arrived. We went to pray. This time, in the cellar of a neighbor. One of the worshippers told that his son was listening to Radio Moscow and heard that on that same day, that is to say, September 17, 1939, Russian troops advanced towards the Polish border. They had already crossed the border in a few directions, in order to liberate Poland, and they had already conquered Baronovitz, Stolpce, and were approaching Bialystok. Great joy burst out among us. Meanwhile the Germans caught tens of people, most of them Jews, loaded them onto a vehicle and brought them to the Jewish hospital on Varshavski Street, tasked them with removing the straw from the mattresses and to fill them anew. At the conclusion of the work, they stood them next to the wall and shot all of them, and buried them there in the yard.

On the next day the Russians entered Bialystok, and the people began to emerge from their hiding places. The joy was great. They danced out of great joy. The young people jumped on the Soviet tanks, and circled the city on them.

[Page 376]

I said to Hillel that I didn't want to remain in Bialystok anymore, that my heart was drawing me home. I took a little food in a rucksack and went with the Russian army to Augustow. I came home and I was happy that I found them all. During the whole time of my absence the Germans did not enter Augustow. The border stabilized as follows: Ratzk, Suwalk, Filipova, and all the area were under Russian rule; 8 kilometers before Augustow the border stood on the bridge from Suwalk to Augustow in Shtzavra-Olshinka. On the other side, on the dirt road to Ratzk, Bianovka, the border remained as in the time of the Poles; Grodno, Bialystok, Grayevo, Osovitz, were in the hands of the Russians.

From the time that the Russians reached Augustow, they quickly found helpers for themselves. Many Jews found upper- and middle-level jobs with them, in both the police and the N.K.V.D.[3] Many felt the power of their arm.[4] They informed on party activists of all streams, who were exiled because of it to Russia. They revealed storehouses. They found a big storehouse in Popkin and Rotenberg's attic.

In this way they confiscated produce, stores, sawmills, flour mills, and more.

The Russians entered Augustow, continued to advance to Ratzk, and stayed there 3 days. They were in Suwalk for a day or two, and then they retreated, and were stopped at the new border, as I detailed in the previous paragraph. Before their retreat, most of the Jewish officers, and also the Russians from the Red Army, advised that the Jews come with them, since the Germans would enter these towns according to the agreement that was signed between the Russians and the Germans. They put at the disposal of every family that did not want to remain with the Germans, a vehicle to transport their possessions and people. In this way, a stream of refugees began to stream from Suwalk, Ratzk and more, towards Augustow. Very quickly the city filled with refugees, and the crowding was great.

In the month of April 1940, the order came from Moscow that all the refugees had to distance themselves from the German border by 100 kilometers in the direction of the old Russian border, to the area of Baronovitz and Slonim. Whoever wanted was able to cross the border to Russia. In this way the refugees were forced to leave Augustow. Part of them wandered to Russia, but most remained in the area of Baronovitz-Slonim. This part was slaughtered in the first days of June 1941, by the Germans, with the outbreak of the Russian-German war.

At the beginning of the year 1940 it was publicized that everyone who wanted to, could travel to Russia on condition that they would obligate themselves to work in it for a year or two. They promised the volunteers everything. Part of the Augustovi youth signed the agreement, and after a short time they travelled to Russia. When they reached Russia, they were sent to work in the coal mines, which were in the distant Ural. Some of them fled from there by all kinds of ways, and returned to Augustow. Among these, I remember only a few individual names: Pshashtzalski (the son of Mushke Dundah), the youngest son of Hershel Meltzer, my uncle's daughter Shulamit Sarvianski. A few weeks after they returned from Russia, they were sentenced by the Russians to imprisonment, until the period of each one's volunteering was complete, according to the work contract that they signed.

[Page 377]

There were also those who did not flee from their work, and completed their period of obligation in peace. There are at least three of them in the land: Shayna Zielaza, and the Levinski sisters.

In February 1940, the expulsion began, and it continued in March and April. The Russians were deported to Russia, the party activists, business owners, and those with money. People were also deported who could not afford to pay taxes. People closed stores, butcher shops, etc. In their place new businesses sprung up, mostly buffets, and shops for writing materials, which were supported by the army that was camped in the city. Most sought work or a job with the authorities, in order to be saved from the expulsion. I too was among the latter. After I closed my shop because of the tax burden, I got work as an administrator of the second shift, at the flour mill of the Borovitz's who were exiled to Russia. The director of the first shift was Stein, who before the war was a shop-owner for writing implements. I worked at the flour mill until they drafted me into the Red Army.

In the Second World War

On Yom Kippur eve in the year 1940, I was drafted into the Red Army, together with a few other friends from Augustow: Chuna Rudnik, the son of Moshele the tailor; Tzvi Pozniak, the son of Shmuel the blacksmith; Moshe Kravitz, the son of Beinish the porter; Barukh Brenner; Feivel Zeimanski, the brother-in-law of Tziporah and Friedka Sarvianski; Beinish (I no longer remember his family name), the son of a shoemaker who lived with Aleksandrovitz; me, and Elchanan Sarvianski, the son of Itshe from Charnibrod. The assembly place for the inductees was the third house from ours, in the house of Chaim Leib. We stood to go out on the train at the hour of 1:00 in the morning, on Yom Kippur night.

With a heart full of sorrow and with tears I parted from my mother, from my two sisters, and from the rest of the relatives. I set out, broken and shattered, for the assembly place. A few hundred Poles from Augustow and the area were gathered there, and us - 7 Jews. There remained much time before the train would go out, and everyone attempted “to kill the time” according to his understanding. Many went to get drunk. I directed my steps to the synagogue, for the “Kol Nidre” prayer, and for “kaddish” after my father my teacher, may his memory be for a blessing.

The synagogue was full from mouth to mouth. Here the Jews of Augustow gathered, with their wives and children, to pour out their conversation[5] and to throw down entreaties before their Master. Holiness saturated everything. All of them were dressed in holy day clothing, wrapped in tallitot and white “kittels.”[6] Here were ascending to the podium Rabbi Azriel Zelig Koshelevski, the gabbai Reb Fenya Ahronovski, and the “ba'al tefillah” with the pleasant voice, the shochet Reb Gedalyahu Gizumski at the head of a choir of boys (among them, his youngest son Shlomkeh). Reb Moshe Dovid Morzinski the shamash, wrapped in a “kittel,” his beard coming down on it,[7] knocking on the table, and a hush is sent throughout the whole synagogue. They open the Aron HaKodesh and take out the Torah scrolls. Reb Asher Hempel passes from bench to bench with the Sefer Torah, and each one kisses the Torah. They finish the hakafah[8] and bring the Torah scrolls to the bima. Here they are placed in the hands of the Rabbi, Reb Fenya, and the Chazzan. This last one opens with the singing of Kol Nidre, and every Jew in the synagogue is helping

[Page 378]

beside him and singing together with devotion. I lift my head and I look at the Jews of Augustow for the last time. Here is Doctor Shor; here is Shevach, the brother-in-law of F. Aharonovitz; here is Dr. Grodzinski; here is Paklof; standing next to me my uncle Leibl Steindem, Velvel Starazinski, and Reb Mottel Leib Volmir with his sons; next to them, Shmuel Sosnovski; behind me, Vilkovski (Manoly the porter), Mottel Staviskovski, and the tailor the “baal tefillah” Reb Mendel Kolfenitzki, and the smith with the beautiful beard; and here – Dovid Leib Aleksandrovitz with his two sons, Alter (Zalman Tzvi) and Aharon; on the other side of the Aron Hakodesh stand Reb Itshe Rotenberg, Manush Kantorovitz, Mordechai Lev, the Lozmans, Shmuel-Yehuda Zborovski and Hershel Meltzer, Yehuda Rinkovski, Chaikel Morzinski with his two sons; and below, “the simple people.” The chazzan concludes the “Kol Nidre” prayer, they put the Torah scrolls into the ark, and all the klei kodesh[9] descend from the bima. The chazzan Reb Gedaliah and his choir approach the prayer “amud”[10] and the Rabbi Reb Azriel Zelig Noach Koshelevski approaches the bima that is in front of the Aron Kodesh, opens the aron, and begins his sermon. I turn my head towards the Ezrat Nashim. There too it is full from mouth to mouth, and the sound of the women's weeping is heard…

The rabbi concludes his sermon and returns to his place. The chazzan opens with the “Barechu”[11] prayer and all the holy nation prays with devotion. There are not secular thoughts now, everything speaks holiness. We reach the “Aleinu L'Shabayach,”[12] and I say the “kaddish.” Tears glisten in my eyes; my heart is broken within me.

Slowly the synagogue empties out. People bless each other with the blessing “May you be signed and sealed for a good year.” I emerge from the synagogue and return to the gathering place. I wandered around there for an hour or two, and there still remained about an hour and a half, the last ones, of my stay in Augustow. I decided to approach our house, in which I grew up and in which I lived for more than twenty years. I entered the yard and I looked in the windows for the last time. My whole family was sleeping. Our puppy sensed me and jumped on the window. I opened the kitchen window and went inside. I listened to the sound of the rhythmic breathing of my dear ones and I went out again. I went around and looked in all the corners of the yard and I went with a broken heart to the induction place. After some time they loaded us on the vehicles and transported us to the train station. Young men and women who came to accompany us waited there. We parted. We went out of Augustow to an unknown land.

The train had already left the sawmill and the “Lipavitz” electric company behind it and was racing quickly towards Grodno. After about two hours it stopped in Grodno. A few wagons loaded with inductees from Grodno, Grayevo, Shtutzin, Vonsozh and their surrounding areas were already waiting for it there. They were joining their cars to our train. The signal was given, and the train moved from its place. We were arriving at Breinsk, and here too they connected cars with inductees to our train. We were passing Volkovisk, Slonim and Baronovitz, in every place the same sight recurring over and over. From Baronovitz the train was skipping to the old Russian border, and we were on Russian soil. All of us were sticking our heads out of the windows, and gazing at the Russian scenery. We were passing by giant factories with tall chimneys. We were arriving in Minsk, the capitol city of Belarus, and continuing to Kiev, Charkov, Dnieper-Petrovsk, Zaporozhe, Tula, Oryol. We travelled a few weeks on the train until we reached

[Page 379]

Rostov on the River Don. We stayed there about half a day, they put us onto vehicles, and brought us a distance of 40 kilometers to Novi Tzarkask.

In Novi Tzarkask, which before the revolution was the capital city of the Don Cossacks, the journey meanwhile was concluded. There were me and another 3 Augustovians: Barukh Brenner, Chuna Rudnik and Beinish, living in the barracks that before the revolution was a palace of Ottoman Cossacks. In a palace-barracks like this, an army battalion entered. The soldiers of our division were from various nations, and there were almost no Russians in it. When we came to the division I said to my friends from Augustow that most of the people in the division were Jews, according to the appearance of their faces. We did not recognize until then the various members of the nations from east Asian Russia, who were partly of the Semitic race. Therefore, I approached them and asked them in Yiddish if they were Jews, and from where they had come. They stared at me and answered in halting Russian that they were Armenians, Azerbaijanis, Turkmans, Tatars, and more.

After some time they finally assigned us and I remained in my platoon with one and only one Augustovi, with Chuna Rudnik. To our luck there were another 3 Jews with us: one from Grayevo, one from Shtutzin, and one from Vansosh. Barukh Brenner and Beinish were transferred to another battalion. They were in another barracks in the same yard, and we would meet each day. After a few days they began to turn us into soldiers. We received clothing, rifles, and all the rest of the equipment. At first they taught us to march, and after a few months – military tactics and shooting. One day followed another, and month followed month. The training became harder from day to day. Time moved slowly. In this way 8 months of my being in the army went by, and only another sixteen months were left to the completion of service.

In the middle of the month of May 1941, our division received an order to gather its people and its “property,” get up onto wagons, and travel. To where? No one knew. We travelled for 6 days until we reached Kiev. In Kiev we got down and went by foot to the area of Biala Tzarkiev. In the forests we dug posts and put up big tents, 16 people in each one. On the next day the battalion went to the bathhouse in Biala Tzarkiev. In the city I encountered many Russian Jews. From them it became known to me that the Germans drafted an army and stationed it on the Russian border. I began to understand why they had transferred us, together with all the northern Caucuses' corps. On Shabbat June 22, 1941, we received an order to put on a full battle belt and to prepare for a race with full military equipment, a distance of 10 kilometers, with gas masks on our faces. The generals of the division and the “Politruk”[13] gathered to take counsel.

Ten minutes before the hour of 12:00, the Lieutenant-General got up and opened with these words:

“Friends! Today, the Shabbat day, towards morning, June 22, 1941, the dark, armed[14] forces of the German Hitlerists attacked our country, without a declaration of war. They bombed Grodno, Berdichev, Minsk, Kiev, and more. They crossed the border, entered Lithuania, Latvia,

[Page 380]

and Estonia. They also crossed the border to Belorussia (that is to say, they crossed the border from Prussia and entered Poland, in the area of our city). The Germans threw into battle thousands of tanks that they plundered from the conquered countries in Europe and from the enormous “Skoda” factories (factories in Czechoslovakia). Our soldiers retreated. It is our job, the soldiers of the Red Army, who are always ready to defend our soil, to enter the battle and hold back the enemy.”

Exactly at the hour of 12:00 they activated the radio, and from it burst out the voice of Molotov, calling to the soldiers and the nation to defend their soil. A shiver passed through my body upon hearing the “message.” All of us were despondent. It was immediately agreed among us, the Augustovians, that if one of us would see his friend killed in the battle, then the obligation fell to him, if he remained alive, to inform the parents of the slain the day and place of his falling, so that the parents would know on the day of the memorial (yahrzeit)[15] to say kaddish for him. At night we went to see a movie that they were showing in the forest. The fabric was hung between two trees, and the movie was military, showing how the Russians were chasing the Japanese Samurais from their soil. During the time of the screening, there suddenly burst out a few German jets. Panic arose. They stopped the screening of the movie. We scattered in the panic, but to our luck they did not bomb us. On the next day with dawn, the brigade distanced itself a few hundred meters from the place, and began to entrench itself.

After a few days an order was given to our brigade to march to Kiev and get on the train that was already waiting for us. We loaded the cannons, the tanks, and the rest of our implements of destruction. On the roofs of the wagons we positioned machine guns to protect us from the planes of the enemy. It was known to me from the officers (I was involved with them, and I became endeared to them) that the objective of the journey was Lvov. The journey progressed slowly, and continued for many days. At every station we were forced to wait a long time. The road was loaded with military that travelled to the various fronts. In all of the stations I encountered trains with Russian and Jewish refugees, who had fled from Poland and Bessarabia. The engines and the wagons were punctured by bullets and shrapnel, the roofs were full of holes and dirt. Trains loaded with machines arrived, whole factories, that the Russians managed to dismantle in order to move them to Oriel and Siberia. Finally our train moved. Towards morning we reached Smolensk. The station was full of thousands of soldiers, and various weapons, which were loaded on the trains. The soldiers from the nearby trains told that they were already waiting in Smolensk for a few days and could not move forward.

Towards morning a German reconnaissance plane appeared that flew very high above the station. Our cannons and machine guns opened fire at it. It flew above us for about ten minutes, and fled. Not an hour had passed when hundreds of German planes appeared above us, and began to rain from their machine guns, and to bomb us and the trains that stood in the station. Panic prevailed. The trains, the cannons, and chunks of human flesh – flew up into the sky. All around the German jets sowed death, and there was no one to give

[Page 381]

an order. I called to my friends that they should jump to the ditches that were at the edges of the tracks. I ran first, and they after me. We somehow hid ourselves until the planes emptied all their munitions and left, leaving after them death and destruction.

From our battalion about 70 men were left. I suggested that we get away from the place before the Germans returned with new munitions. We fled from Smolensk station and directed our steps far from settlements, by way of fields. We passed about 10 kilometers and sat down to rest. And here we see that tens of planes are nearing, from two directions, and flying over us. To our surprise we noticed in one squadron the identifying marks (a star) of Russian jets. In the second squadron were German jets. An air battle developed really right over our heads. Tens of planes went up in flames, and fell next to us with tremendous thunder. The German pilots that were left escaped. The Russians returned to their bases. We decided to flee, but we did not know to where…

After consultation we decided to retreat in the direction of Moscow. We were nearing the main Minsk-Moscow highway. This broad highway was full of soldiers, tanks, and cannons that were retreating from the German military corps. The movement was conducted with great slowness. The beginning and end of the long line could not be seen. On the way one could see tanks and vehicles that overturned on their soldiers when they fell from the high highway to the ditches that were at the edges of the highway. Killed people were seen with every step and pace, and no one was paying attention to them.

There was no room for the retreating infantry on the highway, and with no choice we walked by way of the fields that were next to the highway. After many hours of walking, we decided to sit and rest a little. Russian floodlights lit up the sky, and revealed a number of German planes. You could see the planes well, cannons against planes shooting at them, and always, missing. The German planes were shooting fireworks in the air, illuminating the whole area, and sowing panic. The tankists jumped from the tanks and fled, the vehicle drivers left their vehicles and fled, and we too fled a distance from the highway as much as possible, in the direction of the forest. We hid ourselves at the feet of the hills and in pits, and we waited for what was to come. After some time the sound of a great explosion was heard. At the time that the German planes lit up the highway and its surroundings, and sowed panic within the retreating army. Other planes parachuted saboteurs onto the Dnieper bridge who blew it up. The whole line that was moving on the highway was stopped, for it was not possible to move forwards or backwards. With dawn the German planes came and destroyed everything.

We, the infantry, remained in the forest and dug ourselves in. The hunger bothered us a lot. Over the course of weeks we did not see bread, and human food did not enter our mouths. We existed on wheat, rye, carrots, onions that we found in the fields. We also did not have water. We drank water from the swamps, which was crawling with all kinds of bugs, and stank. I became very weak, and I did not have the strength to continue to flee. My friends were also in the same condition. The day passed, and in the evening we placed our steps in the direction of the town of Dorogobuzh. In the nights we walked on the highway; before dawn we would go down from the paved road, get a few kilometers away, and hide ourselves in the forests all day. The German planes were flying full hours over the forests. Suddenly there was someone from the retreaters shooting fireworks towards the planes, and they were immediately bombing the forest.

[Page 382]

In light of these facts we decided not to allow soldiers that we did not recognize to follow behind us, but this did not help. We saw that German planes were parachuting on the outskirts of the fields, parachutist-saboteurs, in groups of 4-5 men equipped with 85- or 86-millimeter mortars and sub-machine guns that were shooting expanding bullets. We destroyed more than one group like this while they were still in the air. The Germans were parachuting saboteurs day and night, dressed in the clothing of Russian generals and officers. Next to the train stations saboteurs were parachuting in the clothing of train workers, or in the clothing of Russian policemen, and the like. These were destroying bridges and trains, and shelling the army that was hidden in the forests. We finally reached Dorogobuzh. I requested of our one officer that he should put at my disposal a few soldiers and I would go and look for a bakery. My request was granted. I took Chuna Rudnik and another two Russians with me. We found one and only one bakery. It worked for the army, the manager was a Jew, and he was also an army man. In Yiddish I told him our troubles, and that we were hungry, and that bread had not entered our mouths during the course of the entire retreat. He immediately gave each of us a loaf of bread, and we devoured it on the spot. He told us that the Germans were nearing Dorogobuzh, and in another few hours he was abandoning the city. He gave us as much bread as we were able to carry. We returned to our friends and told the news. We ate and rested until the evening.

Towards evening we went out and walked in the direction of the highway that went to Yartzevo. We met many soldiers that had fled for their lives after their defeat at the hands of the Germans in additional places. From them it became known to us that there was no other way to retreat but the road that led to Yartzevo, Yazma, and from there to Moscow. We went tens of kilometers until we reached Yartzevo. Next to Yartzevo we encountered barricades and next to them officers. They called to our officer and asked him where we were coming from and where we wanted to go. The officer explained that we were hit in Smolensk and were retreating to Moscow. The general informed us that we had to remain in Yartzevo. He called to the Polkovnik (Major-General), and commanded him to show us the section of the front that we had to hold. They told us that two days before the Germans had taken Yartzevo, the airfield, the ammunition storehouses that were across the river, and we had to chase them from their new bases. In the evening we would receive reinforcement, and it would be on us to attack. Our officer did not panic, he informed that first of all he had to feed the hungry young men, that food had not entered their mouths for a few weeks, and they had to give them a few days to rest. Food was not given to us, and we did not attack.

After a few days they brought food, weapons, and ammunition, and they also added men in order to bring the battalion up to full size. At the end of July 1941 towards morning the General visited our trenches with his staff. He said that on the next day in the afternoon we would receive an order to attack, jointly with other units, Yartzevo and the airfield that was about two kilometers on the other bank of the river, in order to destroy the German “bridge” behind our line. He asked if we would fulfill the order, and we answered as one: “Yes, Comrade General!”

On the next day, our artillery began to shell the German commando posts. Exactly at 12:00, we began to attack Yartzevo, and at evening time we captured it. We dug ourselves in and waited for reinforcements,

[Page 383]

which arrived after a few days. At the beginning of August an order came to cross the river at night and attack and conquer the airfield and the rest of the areas that were in the hands of the Germans. We went out towards evening for the attack. We crossed the river and advanced without shooting, until we got about 200 meters before the German trenches. Then the Germans sensed us, or maybe they allowed us to approach deliberately. Suddenly they lit up the area, and opened heavy fire from automatic weapons and from tanks that were entrenched in the ground, and created havoc among us. When darkness fell, and the shooting stopped a little, I got up and ran for my life. On the way I heard someone calling my name. By the voice I recognized that it was my old friend, the Uzbek Chadirov. I approached him and saw that he was seriously wounded in the belly. I tore his shirt and his undershirt; I took out a bandage and I bandaged him. I left him in his place, and I ran to the place from which we attacked. On the way I found another friend who was also seriously wounded. Finally I reached the river and crossed it. There I met about another twenty men, among them Chuna Rudnik. I told the officer about the two seriously wounded men, our good friends, who were lying in a place a distance of a kilometer from where we were. He put at my disposal 6 men, and charged me with bringing the two wounded. I went with the “group” by way of the field that bordered the main highway, where it was possible to walk upright. When I felt that we had reached the place across from where the wounded Chadirov was lying, I ordered the “chevre”[16] to cross the road behind me. Not one of them moved. The four Russians announced that they would remain in their place and provide cover for us. I explained that in another half hour it would be dawn, and we would be unable to return. They insisted, for they were afraid. I threatened them that I would tell the officer that they did not want to fulfill an order, but despite this they were frightened, and remained. I and another two – one of whom was Maniak Grayevski – climbed to the edges of the highway (the highway was 15-meters high in that place, and I deliberately chose that place).

With the “Shma Yisrael”[17] prayer in my heart, I crossed the road peacefully, crawling. I waited for the other two to cross also, but they were afraid and did not move. I was forced to return to them, and with difficulty convinced them to cross after me. We came down from the highway, loaded the wounded onto a canvas sheet (which served also as a tent, a coat, and a sheet), and we began to walk. The body of the wounded man was on the sheet, and his feet dragged on the ground. He screamed from all the pain. I explained to him that he should not scream, lest the Germans hear and open fire, but he apparently could not overcome the pain and he screamed the whole way. It was difficult for three men to carry him. The two of them held the front edges of the sheet. It was pleasant and easy for them, I held onto the two edges of the side with the lower part of his body. The feet that were dragging on the ground interfered with my walking. I made an effort and carried him with what was left of my strength. I asked the Grayevi to switch with me a little – he would in no way agree. At that moment the Germans lit up the area, shots were heard, and this Grayevski grabbed his chest with his hand and screamed “Ma…” He did not have time to say the word “Mama” and fell on me killed. The wounded Chadirov also received a bullet from the same burst, which killed him. We left everything, the two of us lifted our feet, and fled in the direction of the river.

We crossed the river in peace and joined our friends. In the afternoon a special runner came from the Division Staff, bringing the news that in the evening a new brigade that would relieve us. The brigade that came was made up of men dressed in civilian clothes and their weapons were one rifle for every two or

[Page 384]

three. There were many adults among them. They were refugees from the towns that were conquered by the Germans. We left that section and walked along the river until we reached a giant fabric factory (the second largest in Russia). They ordered us to enter the factory and settle in there. We sent a few men to bring potatoes from the fields. The “chevre” brought potatoes and a few chickens that they caught, and we prepared a meal. We ate and lay down to rest under the machines, so that we would be protected from shells and shrapnel. I was deathly tired, and I immediately fell asleep. In my dream a beautiful man came to me, adorned with a black beard and a large kippah[18] on his head, and he resembled my grandfather Reb Shmuel Yosef, who I had never seen, but I recognized him from a picture that was hung on the wall of our house. He caressed me, placed his hand on my shoulder, and said: “my son, tomorrow you are going to an attack. Go, don't be afraid. Don't submit and don't hide yourself, for you will not be killed, although soon you will be wounded.” I woke up terrified. A cold sweat broke out on my forehead, but I was happy, and new hopes awakened within me. Until the end of my life, I will believe in the dream.

Towards evening they sent us reinforcement. From the day that we entered the battle and until this very day, we remained 16 veteran soldiers in our brigade. We guarded each other as much as possible. We all received ranks. Some were division commanders, some were in contact with the division, and some were in the “Staff.” We were very connected to each other.

Meanwhile the Germans broke through the Russian defense lines. They conquered towns and came near to Yartzevo.

The next day an order came to prepare for the attack. The engineering force prepared a crossing from rafts on the river. Half an hour before 12:00 the Russian tanks opened up with shelling on the German positions, and exactly at 12:00 in the afternoon the order came to attack. We began to advance. Part of us had time to cross on the rafts in peace. But when the turn of the second half came to cross, the Germans noticed them and opened with terrible cannon fire. Shells fell on a raft and destroyed it. There were many sacrifices. We did not wait, since we were afraid to lag after other brigades, and we attacked. We advanced quickly and conquered the train station and another few villages. We did not have time to dig in, and the Germans opened with a total counterattack, with the help of ten tanks. They were arranged in rows head-on, and began to advance towards us, while they were drunk and shooting from sub-machine guns. They didn't even duck. We allowed them to come close and then we opened fire. The first line was almost destroyed but about 100 meters after it marched a second row, a third, etc. – all of them drunk. We destroyed row after row, and they did not stop walking on the corpses of their soldiers and to come near us. We could no longer hold the position and we retreated about a kilometer. We entrenched ourselves in a four-story school. Around it we positioned mortars and machine guns. Meanwhile reinforcement reached us and entrenched itself behind us, and all of us together shattered the counterattack. The Germans suffered heavy losses and retreated. The night came. Under the cover of darkness more reinforcements of men and artillery came to us, and took positions. The next day we continued the attack. The Germans retreated and we advanced slowly. In this attack I lost the last Augustovi – my friend Chuna Rudnik. I did not see him again.

On September 12, 1941, on Shabbat before the afternoon, when I advanced in the attack with my friend the last Jew, about 40, from Minsk (I no longer remember his name), a shell exploded next to us. My friend

[Page 385]

was thrown into the air and torn limb from limb, and I fell wounded and unconscious on the ground. After some time I began to feel cold, and slowly my eyes opened a little. There was no one around me. I got up from the ground and felt myself, to convince myself that I was still alive. I felt the injuries; the mouth and the bottom half of the nose were torn, the upper jaw was broken, and also eight upper teeth. Shrapnel penetrated my cheeks and the area of the eyes. I took out a handkerchief that was dirty with ash, put it on the torn mouth, and began to run with the remains of my strength towards the river that was next to the forest. I knew that the Division Staff was there in the forest, and a temporary hospital. On the way I met a compassionate brother and requested that he bandage my wound. He put a bandage on my mouth, but it was dropping and falling. I was forced to hold my hand on my mouth. I requested that he help me to go and show me the way. He refused. He was afraid because there was heavy shooting in the area, and it was impossible to walk at full height. I took out the pistol that was with me, aimed it at his chest, and said that he would go with me or I would shoot him, and the two of us would die here. He was terrified, and so with difficulty I got to the bank of the river and fell. A few soldiers caught me and took me across the river on their backs. They brought me to an underground clinic or hospital. My face swelled up and shut my eyes. I became blind and deaf. I also could not speak. The hunger troubled me greatly. For two days food did not enter my mouth. Finally someone came, patted me on my shoulder, and said something to me. I requested that he speak loudly. He asked if I needed to go out. He supported me and I walked after him. Afterwards he returned me. After some time he came back and took me to the office. There they asked me what brigade I was from, what was my name, and the name of my family. They did not understand me, so I requested paper and a pencil. With one hand I opened the eye and with the second hand I wrote. At night they loaded me with other wounded onto a vehicle and brought us to the forest. Underground were two hospitals. There they sutured the wounds and took out the shrapnel and I began to see again. The next day they took me, with a group of severely wounded, and brought us to the airfield, a distance of a few hundred meters from the hospitals. They put me and another wounded man on a plane (every plane took two wounded people), and transferred us to Kondrova. After the emergency room they transferred me to Murmas and from there to Viksim in Gorky district. I lay there for two weeks.

The front got closer to Moscow. They began to evacuate the military hospitals that were found in the areas of the range of the bombs of the enemy. For this purpose a sanitary train came. They transferred all the seriously wounded to the train. After two days it went out to the long way to Siberia. The sanitary train was equipped with beds, with doctors and nurses, and they performed operations in it. The wounded who were able to walk would pass from car to car looking for acquaintances. I too was among the walkers. The Russians recognized that I was a Jew, would belittle me, and ask “why aren't you like all the Jews, who sit themselves far from the front in offices and live it up? You, loser, went to the front, and here, see what shape you are in.” They liked me and would share with me in everything. On the second day of travelling, during a friendly conversation with the wounded, I discerned in one that his hand was put in a cast. I “suspected” that he was a Jew, I approached him, and asked him if he was “amcha” (this is a sign of recognition between Jews). He denied it. The next day I asked him where he was from. He answered that he was from Belorussia. I pressured him to tell me from exactly what place, and then he clarified that he was from Lomza.

[Page 386]

The train swallowed up the vast distances of Russia. Here we were in Kazan, and here is Orel. On all the roads were trains loaded with soldiers. The Siberians were travelling to defend Moscow, the capital. In every place our train was delayed a few days and allowing the military trains that were hurrying to the front to pass. Very slowly, after a journey of six weeks, we arrived at Novo-Sibirsk. They took some of the wounded off the train and moved them to hospitals, and I too was among them. The hospital that I arrived at was new and stood on the main street, across from the unfinished opera building. In the hospital they received us warmly, since we were the first wounded that reached Siberia.

In February 1942, my wounds were healed. They also made me eight false teeth, but while eating they would fall out. I almost swallowed them. I went to the doctor and demanded that they make the teeth on crowns for me. She refused. I got agitated and I hurled at her: “Is this my reward for coming from Poland and spilling my blood to fight for you? I will not go to the front again.” Not an hour went by, when a messenger came and invited me to the Commissar. The Commissar began to interrogate me about what I said to the doctor. I told him that I requested that they make me good teeth. He said that I slandered the government and I said that I would not go to the front. He commanded to bring my clothing, and put me into a room whose only furniture was two wooden beds without mattresses. The cold in it was terrible. They locked the room, and outside the door they posted a guard. Hours went by. I very much regretted the slip of the tongue that had brought this kind of trouble on me. My mind began to work vigorously. Suddenly there flashed in my mind a wonderful idea, which indeed was what saved me. I knew that the Director of the hospital was Jewish, an adult woman at the rank of Colonel. I decided to go see her, be what may. I knocked on the door of my cell and asked the guard to bring me to the bathroom. On the way I noticed the room of the hospital Director. In the blink of an eye I opened the door and entered the room, running, when the guard grabbed me by my robe. I said that I wanted to speak with her about an important matter. She ordered the guard to go out, and the two of us remained in the room. I began a conversation with her in Yiddish, and I told her that I was a Jew from Poland, that I was wounded in battles, and the Germans murdered all the members of my family, etc. I added that the division administration was anti-semitic, and that I was worried about my fate. The speech greatly influenced her, and tears glistened in her eyes. She quieted me and promised that tomorrow they would free me from imprisonment. I returned to my room, but I could not find rest for my soul. My worries and my fears were very great. I closed my eyes, but I could not fall asleep. And here I hear that the door to my room was opening, and a person in civilian dress was entering. He seated himself on my bed and asked why I was placed in detention. I told him everything, he said goodbye, and he left.

On the next day they freed me. I wandered around in the hospital about another ten days.

On February 27, 1942 I went out of the hospital with a group of soldiers to a selection place.

The selection station was full of soldiers who had recovered from their wounds, with Soviet soldiers from the areas of the German conquest, with soldiers that came from the areas that the Russians had conquered from Poland, in Serbia, Lithuania, and more. All these the Soviet regime returned from the front, or did not allow to travel to the front, since it did not trust them.

[Page 387]

In addition to these, there was a Polish battalion from General Andres' army, that was preparing to travel to Iran. In one of the corners of the selection station was a buffet that sold various drinks and sauerkraut. I stood in line to buy cabbage. I felt someone put his hand on my shoulder, turned my head around and was amazed. Before me stood the Lomza'i with whom I travelled in the sanitary train. This time he did not deny that he was a Jew, and added that they called him Yoske (he is in the land). We became friends. We walked around together in the station, and found many Jews from Lvov, from Stanislavov, from Kishinev, and more. I was afraid lest they send me to the front again, and I decided on a daring step. I told my new friend about my plan, to enter the office of the station commander and demand from him a transfer to the Polish army. He hesitated, but in the end he agreed. I approached the door of the commander's office, opened it, and entered, and after me, my friend. Across from me sat the Station Commander, the Major-General. I saluted, and requested permission to speak. When I made my request, I told him that we were from Poland, that we volunteered for the Red Army, that we spilled our blood for the Soviet homeland, and now we were requesting that he transfer us to the Polish army, in which our relatives were found. After a short consultation, the General responded that for the time being we would work in the rear, and when there would be an additional recruitment to the Polish army, they would inform us. We were also happy with this answer, and we went out in peace. The next day the managers of factories, construction works, and army storehouses came to the sorting station to recruit workers. Each of them passed before us, while we were standing in a row, and asked for various professionals, or someone who graduated elementary school. My friend and I were in one group. They loaded us on a vehicle and brought us, by way of the forests, to the Anskaya train station. There they gave us food, money, and clothing, and sent us to the bathhouse.

The next day the manager explained our role to us. He said that it would be good for us if we would work in order. He asked each one about his education, and according to the answers assigned to each one his place and type of work. They set me up as helper to the manager of the division. In the division worked hundreds of civilian women, who would arrange and bind and count the army clothing, shoes, etc. Over the course of two weeks they called me to the office and said that they were thinking about appointing me manager of the division, but I had to know, that I would need to check the women workers each day, that they had not stolen something and tied it on their bodies. If God forbid something should be missing from the monthly stock, then I would be responsible. I heard these words and immediately answered that I did not accept this kind of responsibility on myself, since I struggled with Russian writing. They transferred me, therefore, to the role of guarding the main exit. I was obligated to check and to count the fabrics, the shoes, etc., that were registered in the transport certificate of every truck and also to feel in the clothing of all the workers and the officers that were going out. My friend stood in the passageway behind me in the same role. We agreed between us that we would not get entangled in unkosher activities. It happened, that they loaded onto one truck more than had been declared on the certificate, and the officer who was responsible for the truck would come and offer me a bribe. I always rejected such offers. My work was interesting, I earned well, the food was excellent, I received clothing, and it was very good for me.

Half a year went by and I became ill with fever. For about two months they treated me without success. Finally they dismissed me. My friend quit, since he did not want to part from me, and they sent the two of us back to Novo-Sibirsk, to the sorting station.

In the sorting station they drafted me and my friend to a work battalion. This was a big government company. Its role was to serve all the army brigades in Novo-Sibirsk and the surrounding area. I and my Lomza friend were sent to building work, to carry bricks and more. We saw that it was nasty business, and did not

[Page 388]

go out to work. When the supervisor threatened us, I told him that we were not political convicts, but rather, wounded, and that we would not work unless they arranged guard duty for us. Meanwhile all of them were assigned to various work, but for me no suitable place was found. I began to walk around in the market. I met Jewish merchants from Kiev who fled to Novo-Sibirsk during the time of the war, and managed shops for cotton wool. The dealings were not kosher. Most of the managers of warehouses and shops in the city were connected to each other, and supported by each other. I entered into this “commerce,” and I earned a great deal, until they informed on me that I was not working, and gorging myself on everything good, while they, the Russians, were working hard and didn't have enough food. I was invited to the Commissar. There were with him another 7 men who didn't want to work. He asked me from where I had money and clothing and so much food, in a time when I wasn't working at all. I denied everything, but he sent all of us, accompanied by guards, to the police commander, and asked that he arrest us as “refusing work.” The commander asked each of why we did not want to work. I answered that I was severely wounded, and that I could not carry bricks, and that I was ready to engage in guard duty or something like that.

I was appointed as a supervisor of a large stable. My job was to feed the horses, to clean the stable, to distribute to the waggoneers, etc. There were six workers who worked in three shifts. I worked with one other 24 hours straight, and then two days we would rest. On the free day off I would engage in selling. I also brought the Lomza'i into the business, since his situation was difficult. Selling was more than enough for all of us.

One day I returned from the market feeling unwell. My head was feeling dizzy, my appetite disappeared, and my knees were collapsing. I lay down to rest. My temperature went up and I almost lost consciousness. My friend Yoske ran to call the medic. He came, checked me, and determined that I was sick with a type of typhus. He filled out a questionnaire, and sent me to the hospital for infectious diseases. I went by foot. I reached the hospital with difficulty, and there was no room, and they directed me to another hospital. It too did not accept me. When I reached the fifth hospital I collapsed, and fell unconscious. I returned to consciousness over a course of two weeks. Since in the nights I would get up from my bed and wander around the room, they would tie me to the bed. After two weeks, the crisis passed and a binge of ravenous hunger attacked me. I would eat all the portions of the unconscious soldiers in my room. The water that was in the bottle was not enough for me, I always asked for more. A fire burned within me. After a month they permitted me to go out of my room. I went into the bathroom, opened the faucet, and drank a lot of cold water. The next day I was sick with dysentery, and I lay another month. I left the hospital in the middle of the winter and went to the “barrack.” I did not have the strength to walk upright, the wind and the ice hampered me. I preferred to crawl on my knees to the shared apartment. There my friends met me, and immediately cooked potatoes in a large pot for me, which I swallowed quickly. They told me that after I got sick, a wave of typhus broke out in the “barrack.” The medic got infected from me, and he infected almost all of them. They took him to the hospital and he died there, and another few men died. My friends went to visit me in the hospital where I had first been sent, and they told them that I was not there. They thought, therefore, that I had died. Slowly, slowly, my strength returned to me.

[Page 389]

The months went by. I, with my partner, engaged in selling in our free time, until on one bright day, my friend Yoske was caught with a cargo of merchandise. The policeman confiscated the merchandise, and invited him to walk behind him to the police. In this way the policeman gave, intentionally, an opportunity to my friend to flee, in order that the merchandise remain in his hand, and he would not have to turn it over to the government. The matter recurred over and over each day. Things reached a point that my friend could not engage in selling in that city, and moved to sell in another city.

Immediately after I got well, I left the barrack and moved to live in a private house, with Russian people. The landlord and the members of his family were good-hearted people. They did not agree to receive the rent; sometimes I even found, when I returned home, that my work clothes had been laundered.

One day, at the end of the year 1943, I met with my friend from Grodno, Yasha Kobrinski. He told me that he met one Augustovi in the draft office, and his name was Alter Kaplanski. I was very happy, for not only was he from my city, but he and his parents lived near us for many years. I succeeded in finding him, and from that day we would meet very frequently. He told that he was working as a fuel warehouse man. Once, he told me and my friend, that he could sell fuel, and that the drivers were prepared to pay any price. We advised him not to engage in this.

Alter was a regular guest by me and by friend over the course of about half a year. Suddenly his visits stopped. When two weeks went by and he didn't come, I went to his apartment. His landlady told me, weeping, that about ten days before emissaries from the N.K.V.D. came in the night and took him. We tried to investigate his fate, but it was told to us by a friend of his that we should not look for trouble…in this way I lost my neighbor and my fellow townsman.

The war was continuing. The front required reserves. Already they were drafting almost everyone, even the “politicals.” Men from the draft bureau were coming to the factories, the warehouses, and the like, closing the gates in order to not let anyone evade the inspections. They were also stopping men in the markets and streets of the city and checking their release papers. Only those who had great “protectzia”[19] succeeded in being released. In an atmosphere like this, my turn came, too, to present myself for inspection. In the medical examination I was classified as fit for the front; in the political examination, as unfit, since I said that I was from Suwalk, which did not belong to the Russian protectorate, but to Poland. The chairman, a Major-General, looked at the map that was hung on the wall, and ruled to free me and three other Jews, since we were from Poland. We remained to wait until we received our release papers. After the chairman and the doctors had gone their way, an officer nevertheless ruled that we had to present ourselves in three days at the train station, in order to be sent to the front. We were afraid to open our mouths and we went to pack our belongings. I succeeded in selling part of my possessions, part I left for my good landlords.

[Page 390]

At the appointed time we presented ourselves at the train station. On the next day we reached Kamarova. There they trained us without a pause.

After two weeks of difficult training, the order was given to go out to the front.

The train went out on a long road. It travelled with great speed to the front, in order to crush the Nazi animal. We went by Novo-Sibirsk, the city where I spent 2 ½ years. We passed Omsk and Tomsk, reached Kazan, and from there to Moscow. Day and night I was sitting by the window, and looking at the wonderful scenery of Siberia and Oriel, and my eyes could not get enough of seeing. In every direction, from Vyazma on, one could see the traces of the Germans, who burned or cut down the forests and the settlements, in a diameter of a kilometer or more, from two sides of the iron tracks, from fear of the Russian Partisans, who blew up and took down the German trains that were loaded with soldiers and tanks. The train went by Smolensk, Minsk, Hummel, and was approaching Vitebsk. The front was already very close. Before the old Russian-Polish border, from before 1939, the train was stopped. We got off next to the Molodizhna forest (if I am not mistaken), which only a few days before was conquered by the Russians. The forests were full of thousands of soldiers and thousands of modern implements of destruction. Here they divided the soldiers into brigades that were needed for reserves, after they had been thinned out in the battles. I, and about a dozen[20] Jews from Stanislavov and Bessarabia were joined to the 695 Foot Brigade, from the 221st Division, which belonged to the Belorusian Third Army. The Commander of the Army was the Jewish Marshall Tchernichovsky. We rested in the forests for three days. Each one received his weapon and all the equipment of a battle soldier. On the next day the order was given to go out to the front singing.

We crossed the old border. We entered the towns of Soly, Keni, we conquered Smorgon, Oshmyani, and Stara-Velika. We advanced towards Vilna. The Germans began a speedy retreat. It was really a “pleasure” to see how the “heroes” were fleeing, and leaving everything behind them. We did not have enough time to chase after them. A battle over Vilna developed. Our brigade conquered the train station and the surrounding streets, and the rest of the brigades completed its capture. After the conquest of Vilna, we got a day off. After a day of rest, we entered the battle and conquered a few villages, we crossed the old Polish-Lithuanian border, and advanced towards Kovno. We crossed the river Niemen quickly on rafts, and entered the city together with other brigades. We received a few days of liberty to fill in our brigade, whose men had dwindled in battle. I went with my friend to the Kovno market to buy brandy and various foods. I noticed there a Jew and a Jewess. I asked them in Russian if they were “amcha” (Jews). They answered that they were not, but when I began a conversation with them in Yiddish, they told me that they were Jews, and that they had emerged from the forest only two days earlier. They looked in every direction, gripped by fear, asked me not to speak with them, and left. After we rested, the Major-General came for a visit and announced that our brigade had been given the job of conquering Mariampol. On the next day

[Page 391]

the cannons and the Katyushas opened up with great noise, and in face-to-face battle we conquered the city. As a reward for our heroic acts, they called our division The Mariampol Division. The corpses of the Nazis lay everywhere, and there were very many captives in our hands. We didn't know what to do with them.

After the capture of Mariampol, we advanced quickly to Kalvaria. We entered into very heavy battle, since Kalvaria lies on high hills. Within the hills were reinforced concrete fortifications. We advanced in the tanks to Kalvaria, and in face-to-face battle we conquered it. The Germans fled in every direction, we pursued them, and we also conquered Vierzblova. We reached the Lithuanian-Prussian border, next to the great Masurian lake. We had no more strength left to pursue. We remained few, and tired to death. Over the course of weeks we almost didn't sleep, and we didn't take off our shoes. On our toes great wounds developed from sweat and decomposition; the men fell and fainted from the super-human effort. When Marshall Tchernichovsky saw that his boys were unable to move from their places, he gave us another day's rest, and commanded to bring a military band. Afterwards he began to speak to us. In his surveying the long way that we had crossed until we reached the border of the Nazi animal's lair, he said to us, that here, in its lair, we needed to destroy it once and for all. When the sign was given, the band began to play, the soldiers arose, and the feet began to march by themselves.

To the sound of the music of the band, we crossed the German-Lithuanian border and entered Prussia. Every house in their villages was built in strategic fashion. In every house, a reinforced concrete basement, which was able to withstand artillery fire. The most effective weapons against fortifications like this were grenades. One had to capture house after house. In conditions like these we advanced towards the holding of the German Air Marshal, the Nazi Goring. We conquered the bridge, made of concrete, adorned with statues of lions and stags, that was on the river, and advanced about two kilometers by way of a thick and well-kept forest, to Goring's palace, which we conquered at night, in face-to-face battle. We rested there and in the morning we advanced forward and conquered villages and farms. In those villages and towns we did not encounter even one German citizen. They fled a few weeks before this, when they heard that the Russian army was rapidly advancing, and when they saw that the German army was retreating. We approached Goldap without resting, pursuing the fleeing German army.

We received an order to get up on the tanks. We entered Goldap, which was full of German citizens and army men who did not expect us at all. We jumped from the tanks and began a face-to-face battle. The tanks destroyed mercilessly. Finally we conquered Goldap. After a few hours the Germans recovered and moved to a counterattack, and reconquered Goldap. We retreated about two kilometers from the city, fortified ourselves, and dug ourselves into the German cemetery. We did not have enough men with which to attack. The men and the weapons dwindled in the battles. We waited for reserves.

At the end of October 1944 an order was received that the whole battalion would go out for a day tour, in order to check the German strength and equipment that were arrayed against us, and to catch German soldiers alive from whom it would be possible to extract information. The Major-General himself oversaw the operation. He commanded to bring very many cannons and Katyushas, which opened heavy fire on the German positions. Under cover of fire we dashed

[Page 392]

forward and we reached the German posts. We threw grenades and created havoc among them. The captive soldiers told that they were from a Hungarian brigade, while others were from a battalion of Poles (folksdeutchen).[21] We understood that arrayed against us this time were not Germans, but rather their Hungarian and Polish partners. They revealed to us where the brigade staff was. Our Commander asked who volunteered to go out about thirty meters forward from our posts, to be a sniper. My friend, who was a commander of a squad, volunteered and went out with a sniper's rifle. The next day he came and told me that he discovered the place of the German staff, and that the way was possible under his sniper fire. He suggested that I go with him to see how he was destroying Germans. I acceded to him. And indeed, we would only see one German on the way – a bullet was expelled, and the German was no more. This “game” very much found favor in my eyes. I immediately requested a sniper's rifle, and I remained with him to hunt “Fritzes.”[22] We sat together in that cemetery for about three weeks and sought prey. When German appeared in “our territory,” we immediately killed them. The Germans noticed this, and started seeking us with the help of shelling. In the last two days they covered our approximate territory with hundreds of shells, which exploded in front of and behind us.

On November 29, 1944, the German shells found us. When a German shell crashed right next to me, on the left side, I was wounded and fell covered in my blood and unconscious. After a time, when I returned to consciousness, I stood up in great pain and I saw my friend Dmitry Bogoslavitz from Stanislavov sitting in his place at the post. I yelled to him that he should bandage my wound. When he did not answer I kicked him, until I saw that blood was dripping from his head and congealing on his forehead. I understood that he was not alive. I ran in the direction of the posts, which were full of mud from the rain and the snow, until I reached my friends. An orderly bandaged me, and transferred me to the hospital that was next to the division. I felt strong pains in my head, which was wounded, as if hammers incessantly pounded in it, and in my back, which was wounded by shrapnel to the depth of the left lung from above, and in my left hand, which was paralyzed. They immediately tore off my shirt, which was red with blood. I lost consciousness.

When I regained consciousness, after three weeks, I was in the hospital in Kovno. Next to my bed stood 6-8 doctors who asked me how I feel, and what hurt me. They consulted among themselves and told me that they would give me a blood transfusion, and that after two days they would operate on my head. I asked them what happened to my head, and they answered that the skull was fractured, and inside, until the membrane of the brain, there were many shards of shells of all sizes. Besides that there was also shrapnel in the skull bones, and they had to at least remove these, for they were endangering my life.

After two days they gave me various injections and took me to the operating room. Among the surgeons I recognized that one was a Jew. He had a typical Jewish face with an eagle nose. I saw that they wanted to tie me to the table, and I said that I would be quiet and ready for everything, and that they should not tie me. I began a conversation in Yiddish with the surgeon, and I asked him to spare my life. I told him who I was, and from where

[Page 393]

I came. I saw that my story touched his heart. They put a sheet on my head, with an opening, and I immediately felt that something was stuck into my head, and was cutting. The whole time the surgeon was talking to me in Yiddish and asking me about my home, and who remained there, and I answered him with difficulty. I felt strong pains, and I asked the surgeon to do something to quiet them. Afterwards I felt that the surgeon was working with “tweezers” and saying to me that I should not move my head even one millimeter, since he was removing shrapnel from the membrane of my brain, and if I moved, the tweezers was likely to puncture the brain, and then I would be lost. When I heard these things, I tried with all my strength not to move my head. When he finished taking out the shrapnel, they stitched the skull, bandaged it, and put me into a room for the severely ill (two in a room). Meanwhile my face and my head swelled up, and I couldn't see anything for a few days. I couldn't walk around or move, and when one side hurt from prolonged laying on it, I asked the nurse to turn me to the other side.

Days passed, the swelling went down, and I was already able to sit up in bed. Very slowly, I began to get off the bed to go to the bathroom, holding the wall with one hand, and my head with the other. Very slowly I got stronger, and I began to walk around in the hallways. The doctors decided then to send me to the rear.

On one of the cold days of December of the year 1944, they transferred me from the hospital in Kovno to a sanitary train that was collecting all of the severely wounded that were being sent to the rear to the various hospitals.

Me they brought to a giant hospital in the center of Ivanovo, near Moscow, which only took care of head wounds. Immediately the wounded who had been there for a long time surrounded me, and asked me where I was from, and from which front I came from, and what was going on at the front, and how we beat the “Fritzes,” etc. We became friends. We played dominos, chess, and checkers. We would go to see a movie, a performance, comedians, a band of singers or musicians that would very frequently come to entertain us and lighten things for us. Delegations would come from various organizations and from factories and bring small gifts: notebooks, envelopes, pouches for tobacco (Makhorka)[23] that were made by hand and embroidered by hand. Every gift had a small letter included, with an address, asking the wounded man to reply to the sender of the gift. In this way the wounded found friends among the citizens that would come to visit them; after their recovery the wounded would visit in the houses of their friends.

The wound on my head continued to heal. The hand and the back healed on their own, without the care of doctors, but there remained in my back much shrapnel, and one piece was next to the left lung. They are there to this day. Another two weeks went by, the wound in my head was almost healed, but there remained a wound the size of a match head, which according to the calculation of the doctors should have already formed a scab, but it remained open and was oozing pus. The matter aroused the doctors' suspicion, and one day I was called to the doctors' room, in which was also the Director of the hospital, an adult Jewish woman, who recognized me from her visits to my room (she knew that I was the only Jew in the hospital). The doctors had reached the conclusion that they needed to send me for Roentgen pictures. After I had the Roentgen pictures,[24] I returned to my room. Together with me in the room there was a Ukrainian by the name of Tzervinski. When I arrived at the hospital, he was already walking around and they thought to send him home, but he had a wound like mine, and they decided to operate on him again. And so,

[Page 394]

they operated on him that same day, returned him to the room, and towards morning he died. The orderlies who came to the room in order to transfer him to the morgue made a mistake, and approached me. I was in deep sleep, but when they took hold of me with their hands and wanted to put me on the stretcher, I opened my eyes, looked at them, and asked them what they wanted. They were confused and stuttered that they sent them to take Tzervinski to the morgue. After I explained to them that my name was Sarvianski, they let me go, and took the dead Tzervinski.

After two days a nurse came to shave my head before the operation. I refused. The surgeon called me to his room and explained that the operation was necessary. I did not agree and returned to my room. After some time, the Director of the hospital, the Jewish woman, sent to call me to her room. I answered her and came. I told her that I was very afraid of a second operation on my head, and the main part of the fear was because of the surgeon, that he was young, and in all the operations that he performed, the patients died. The Director explained to me that pus had accumulated in my head, between the membrane that enveloped the brain and the inner bone of the skull, as a result of shifting shrapnel. Since the external wound had healed, no path remained for the pus to emerge, and there was a danger that the pus would burst the membrane and be spilled into the brain, and then there would be no saving me. She advised me, for my own good, to be operated on that same day. I turned to the Director with a request that she operate on me. She answered that she and the surgeon would operate on me together. That relieved me and I agreed.

They immediately shaved my head, and towards evening of the same day I entered the operating room by myself. There the Director and the young surgeon were already waiting. I got up on the operating table. They injected a few local anesthetics, put the sheet with the opening on me, and after a few minutes I felt the scalpel at work. Blood dripped from my head and went into my left eye. I lay without fear, without moving my head. The Director spoke to me in Russian the whole time. After they finished their work and stitched the wound, they lay me on a stretcher, and brought me to the room. My head immediately swelled up, but after a few days the swelling went down. Two weeks went by, and the wound was healing nicely. After a month I was already walking around without a bandage. Every few days I would go to the doctors' room, where the Director always was, for an examination. Once I complained that a large piece of shrapnel which was exactly next to my left eye was bothering me. They knew about it from the Roentgen pictures. The surgeon offered to operate, but informed that he was not responsible for the eye. I passed on the operation.

Very slowly the time went by. I stayed in the hospital a little longer, and on March 27, 1945, they gave me instructions how to behave in daily life, dressed me in old army clothing, gave me dry food, a product card for the way, documents, and sent me home.

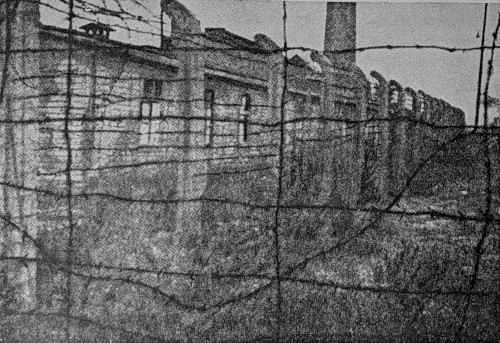

I left the hospital and walked to the city Commander. I requested a free travel ticket to the city of my birth and a permit to cross the border to Poland. He gave me the permit and a free travel ticket to Lublin. In a letter that he sent in my hand to the Commander of the 9th Infantry Brigade of the Polish Army, which resided in the buildings of the Majdanek extermination camp (3 kilometers from Lublin), was instruction to hold

[Page 395]