|

and the candlesticks that were hidden with Christians in the

village. The Christian mother of the family, who was no longer

alive, believed that Shlomo would come to take them.

|

[Page 14 - English] [Page 23 - Hebrew]

Abraham Dragon

I wish to describe my birth-town to the young generation.

The town of Zuromin was a small town with about half of its inhabitants Jewish. They lived in the center of the town. Some were shopkeepers, others shoemakers, tailors, etc. They did not earn a lot of money but they lived respectably. It was a small town but it had a rich cultural life. There was a cheder where Torah was taught. In another cheder, Hebrew was taught. Years before the war, a library was established named after the writer I.L. Peretz. In the great hall of this library, plays were performed, lectures were given, etc. There was also a football team in town.

There were institutions in our town for social services, like bikur cholim, which gave free medical service to those who needed it. In 1938 Tipat Chalav (child care center) was established with the help of Zuromin Jews who emigrated to the United States. In this child care center, they used to give a roll and a glass of milk to every child.

Politically, all the parties that existed in Poland existed in Zuromin too. Life carried on like that until the Second World War broke out. On the second day of the war, all the youngsters – Christians as well as Jews – were ordered to leave the town. The town was attacked by German planes and that was when David Goldak of our town was killed – the first victim of the war.

A short time after that we returned home and no Germans were seen in town on Yom Kippur evening. That night some Germans came to town and made a list of the Jews who lived here. They returned on the morning of Shmini Azeret (the last day of Sukkot) and ordered all men aged 18-45 to be at the municipality at a specific hour. Then they separated the Jews from the Christians. The Christians were sent back home and the Jews were expelled to Lidzbark. There we had to collect potatoes. On that Simchat Torah night the Jewish shul (synagogue) was burnt down.

On Cheshvan 26 (the second month according to the Jewish calander) all the Jews of our town were expelled to Warsaw. On this day a Jew named Izchak Lapko was shot. He was the first victim of the Holocaust (and that was why we decided that this day would be the memorial day for the Jews of our town who were killed in the Holocaust). When we got to Warsaw, we had no dwelling place. So a few families of Zuromin found dwelling in the shul. We, the youngsters, did odd jobs to bring bread to our families. Conditions were terrible. It was very cold and we had no warm clothes. We lay paper on the floor and covered ourselves with paper. This was our only means of keeping ourselves a bit warmer.

After a short period, the Germans established the Warsaw Ghetto and we were left jobless. We used to sneak secretly out of the ghetto, evading the Germans, to bring into the ghetto some potatoes and corn. We would sell the stolen merchandise and use the money we received to get supplies for our families.

A short while later, the Germans planned to send my brother Shlomo and myself to a concentration camp. We left the ghetto secretly and got to Plonsk, all by ourselves. Our parents, sisters and brother stayed in Warsaw. We earned our living by working for farmers in the nearby villages. A short time later we sent a message to Warsaw to help our parents, sisters and brother escape and join us. My father and elder sister stayed in Warsaw because my father was ill and my sister was taking care of him. They both starved to death. My mother, brother and younger sister did manage to escape out of Warsaw and join us, but after a time they were sent to the death camp, Auschwitz. My brother Shlomo and myself were sent to Birkenau, where we met other Jews from Zuromin.

We stayed in Birkenau for over two years. Fortunately we stayed alive. We came to Israel and have been living here to this very day. Together with other people from Zuromin, we decided to build a memorial for our townspeople who were exterminated, on which are engraved the names of the families so that they will be remembered – not forgotten.

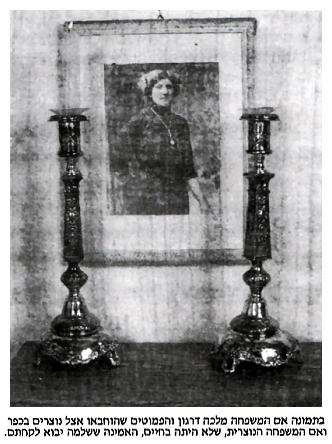

The Fate Of The Candlesticks

The chronicles of the candlesticks are incredible. For 50 years they have been in exile in Poland, knowing nought of Sabbath candles or holidays candles. They lay in exile, mourning their fate, while days, weeks, months and years went by, hoping for redemption, which failed to arrive. Fifty years had passed, and the day of redemption from amongst the “Goyim” (gentiles) had arrived. So many tears had my mother shed and so many prayers had she said when lighting Sabbath and holiday candles, whispering “lehadlik ner shel Shabbat” (“to light the Sabbath candles”). Fifty years, standing, awaiting redemption, which materialized finally. From now on you will once again stand on a Jewish table at Shabbat and at holidays, and we will once again light the candles, and you shall beautify the table with your holiness.

|

|

| In the photograph is the mother of the family, Malka Dragon, and the candlesticks that were hidden with Christians in the village. The Christian mother of the family, who was no longer alive, believed that Shlomo would come to take them. |

[Page 16 - English] [Page 25 - Hebrew]

Shlomo Dragon

Auschwitz, 10-11 May, 1945. The investigating judge of the Krakow district, Van Sehn, member of the investigating committee of Nazi war crimes in Auschwitz, by advice and presence of Dr. Ian Sygmund Rubbel based on Clause 254 regarding Paragraphs 107, 105, 115, and 124 of criminal law. Hear the testimony of Auschwitz concentration camp prisoner, whose number is 80359, testifying as follows:

My name is Shlomo Dragon, born on March 19th, 1922, in the town of Zuromin, Sierpc district, to Daniel and Malka of the Bekerman family (both are not among the living); not married, tailor by trade, Jewish, a full citizen of Poland, who prior to encampment lived at No.1 Biezun Street, in Zuromin, now probably at No.1 Warsaw St.

I arrived at Auschwitz in a transport of about 2,500 Jews of both sexes and varying ages from the Mlawa Ghetto on December 7th, 1942. We were received by the commander of the camp Fluge, Raportfuhrer Pallitch, and the camp doctor, Mengele. As we arrived we were driven through the selection scourge, thus being separated into two groups – women and children in one, men in the other. From the men, 400 were selected (myself among them) to be marched on foot to the Birkenau-Brzezinka camp. The rest of the men were joined with the women and children, and they were all driven by lorries outside of the camp.

Our group was located in Shack 3, in a part of the camp later designated for women. We were later transfered to the old sauna, Building 22 and Building 14 in the same part of the camp. On the evening of December 9th, SS men Moll, Fluge, Pallitch, and Schebe, along with Mikosh the work scheduler, arrived at Block 14. Moll announced that he would select from among us workers for a rubber factory. Each one approached him to be questioned about his occupation and to be observed. If he was regarded strong and healthy, he would be passed to the group of rubber factory laborers. My brother and myself declared we were tailors, and were selected by Moll and his assistants for the labor group. The next day, December 10th, after the groups left for labor, he reached Block 14 and ordered: “SonderKommando out!” We therefore deduced we were part of a special group, and not ordinary rubber laborers. We could not say what this special group was, for we had received no explanation as to our duties. We stood as ordered in front of the block. We were immediately surrounded by SS men who led us in two groups, 100 men each, outside the camp. We were brought to a forest in which a straw-roofed shack stood. The windows were blocked with bricks and on its door was a sign: “High Voltage, Danger.” Thirty or 40 yards away were two wooden shacks. On the far side of the shacks were four pits, 30 yards by 7 yards across, 3 yards deep. The rims of the pits were pitched and charred. We were made to stand in front of the shack, and Moll announced that we were to work cremating old people with lice; we would receive food and lodging within the camp, and unless we worked we would be beaten. He assured us that those who did not work would experience their sticks and feel the wrath of the dogs they brought.

We were divided into several groups. The job of 11 other men and myself, it became clear, was to drag the bodies from the shack. We received gas masks and were ordered to the door. Moll opened the door, and only then did we see that within the shack lay the bodies of people of varying ages and of both sexes. Moll ordered us to take the bodies out to the yard. We started by four of us taking each body, which raised Moll's anger. He rolled up his sleeves and threw bodies into the yard through the door. In spite of his example, we told him we could [editor's note, I believe the word 'not' needs to be added here] work as he did, and he allowed us to resume the work in pairs. When the bodies had all been laid in the yard, a dentist, guarded closely by an SS man, took out all the gold teeth. A barber, also guarded by an SS man, came and cut the bodies' hair. Afterwards, another group collected the bodies and loaded them onto carts that stood on narrow rails, leading to the pits. The rails ran between two pits. One group was busy preparing the pits for the cremation. They first put thick logs at the bottom, thinner branches upon them in criss-cross fashion, and finally dry branches. Another group took the bodies from the carts and threw them into the pits. When everything had been prepared, Moll poured kerosene in the four corners, lit an ebonite comb, and threw it to where he had poured the kerosene. The fire rose and consumed the bodies. During all this process, we stood in front of the shack and watched closely. After the bodies were taken out we were forced to clean the shack, wash the floor with water, spread sawdust and white-wash the walls. The shack was divided inside into four cells: the largest could contain up to 1,200 people, the second 700, the third 400, and the fourth 200 to 250 people. In the wall of the largest cell there were two lattices. The other three had but one lattice.

These lattices were closed by a wooden door. Each cell had a different entrance. On the main door was a sign warning: “High Voltage, Danger.” The sign was seen only when the door was closed, and when open, a sign could be seen saying: “To the Bathing.” Those condemned to die in the cell saw the other sign, posted on the cell doors, which said: “To the Disinfection.” Behind this door there was, of course, no “disinfection,” for it was the door through which we dragged the dead bodies out to the yard. The description of the cell as I have given was drawn by Eng. Nussel of Auschwitz. This cell was called Bunker 2. Apart from it, about 500 yards away, was Bunker 1. It also was a brick building which had but two cells, containing the sum of up to 2,000 naked souls. These cells had only one door and one lattice each. Next to Bunker 1 stood a barn with two shacks. The pits were further away, served by hundreds of carts on rails. At the end of the first working day we were led back to the camp, not to Block 14 from which we left that morning, but to Block 2, to which the second group also returned. As it happens, they were working in Bunker 1. The block was separated from the rest of the camp by a wall. We were forbidden from associating with prisoners from the other blocks. The poisoning of prisoners did not require the whole group. It was usually done at night, when about 20 of the men were picked to help in this work. The poisoning itself was done mainly by SS men, by bringing the people in lorries to the shacks. We would then help the sick to dismount and undress in the room. They all disrobed in the shack. The shacks and the space between them were surrounded by SS and their hounds. The naked people would then go from the shack to the cell. The SS men standing near the door hurried them with sticks. When the cell was filled with people, the SS men closed the door, and Mengele ordered his assistant Rottenfuhrer Steinmetz to commence. He exclaimed “Steinmetz, get it over with!” Steinmetz would then take a canister of gas, a hammer and a special knife out of the Red Cross van, which followed every condemned transport. He would put on a mask, open the canister with the knife and hammer and pour its contents through the lattice into the cell, and close it. He would then take the empty canister, the hammer and knife and put them back with the mask into the car. This van was commonly called zenker by the Germans among themselves. I myself have heard many a time Mengele asking his assistants: “Is the zenker here?” After committing these actions, Mengele and his assistants drove away with the sanitary van and we were brought back to the block. I know not how it was at the beginning, but later on, after such a poisoning, SS guards would stay near the bunker cell. It actually happened that when the bunker was left unguarded, crates of gold teeth which (among other things) were kept in the shacks, were stolen.

The bodies lay in the bunker until morning, when the cremation group arrived. The cremation process was the same process as I described on the first day, when I worked in Bunker 2. The belongings of the dead people were sorted by a special group and transported to the Effectenkammer in Auschwitz. The pits were emptied of ashes, usually 48 hours after the cremation. The ashes still contained bits of bone. We saw skulls, knee caps and long bones, and shoveled the ashes to the pits' rims. Then came lorries, onto which we loaded the ashes to be transfered to the river Sola. There we unloaded the lorries into the river, under close supervision by SS men, of course. The space between the lorries and the water was covered first by cloths, so that not a single bit of ashes would touch the ground. As instructed by the SS men, we would throw the ashes onto the water so they would not sink to the bottom, but be carried away in the current. Afterwards, we would shake the cloths well into the water and sweep the place. The dead bodies were mainly lying down when the door was opened, men pressed together in layers; some were in an inclined position. In many cases I have seen white froth on the lips of the dead. It was very hot inside the cell, and traces of sweet tasting gas could still be sensed. The canisters which contained the gas were made of metal, with yellow stickers, exactly like the ones later used in the crematorium. In both bunkers mainly Jewish transports from Poland, and later on from Lithuania, France and Berlin, were poisoned.

Bunker 1 was completely dismantled by 1943. After Crematorium 2 was built, the shacks next to Bunker 2 were also dismantled and the pits were covered. The bunker itself remained to the end and, after a long pause, was reactivated to poison Hungarian Jews. New shacks were then built and the pits were reopened. Day and night shifts then worked near Bunker 2. I myself worked there for two days. During this period we took the bodies out of the cell a shorter time after the poisoning than before. Therefore it sometimes occured that when we entered the cell we could still hear moaning, especially when we grasped the bodies with our hands to drag them outside. In one case we discovered a live baby who was wholly encased in a pillow. Its head was also covered, and after removing the pillow it turned out that the baby's eyes were open, and it seemed alive. We brought the baby to Oberscharfuhrer Moll, announcing that the baby was still alive. Moll took the baby to the pit's edge, put it on the ground, trod on its neck and threw it into the pyre. With my own two eyes I have seen that when he trod on his neck, the baby moved his arms. He did not cry, so I was unable to determine whether he breathed or not, but nonetheless he seemed different than the dead bodies. Bunkers 1 and 2 contained about 4,000 people, Bunker 2 itself more than 2,000.

In 1943 we were transfered from the women's camp to camp B II D, Block 13, and then on to Block 11. During autumn of that year I somehow was reassigned to the Sonderkommando. In between jobs, I was part of a wrecking team. I worked near Crematorium 5. Until May 1944 I worked in gardening, wood cutting and Koks (coke) moving, since the crematorium was activated only in May 1944, when the Hungarian transports began arriving.

The crematorium work was managed by Moll, and the supervisors were Bogher and Eckhardt. Among the guards were Kurzschluss and Gutz. This crematorium was built like Crematorium 4. In both were four furnaces on each side, each furnace containing up to three bodies. The gas chambers and the disrobing room were partially below ground.

Poisoning was carried out in the same manner as in Bunkers 1 and 2. The people were transfered in lorries, and towards the end, after setting the rails to Brzezinka, I was rushed to Crematoriums 4 and 5. The newcomers entered a wardrobe, rushed by an SS man named Burger, who told them to hurry so the food and coffee would still be hot. People asked for plain water, but he answered that the water was cold and not for drinking; therefore they had to hurry, and when they came out of the bathing they would receive hot tea made for them. When they were all inside, he stood on a bench and addressed them, telling them they had arrived at a camp where the healthy ones would go to work and where the sick and the women would remain inside the blocks. He showed them the boundaries, and told them that they should first bathe, otherwise the camp management would not allow their entry. After everyone disrobed, they were rushed into the gas chambers. At first, there had been only three cells, and near the end a fourth cell was erected. The first contained 1,500 people, the second 800, the third 600 and the fourth 150. From the wardrobe, people entered the cell through a narrow corridor. Inside the cells were signs “To the disinfection.” When the cell filled, SS closed the door. Usually Oberscharfuhrer Moll closed it himself.

Later on, Mengele ordered Steinmetz to carry out his actions, as it was near the bunkers. He would go to the van with the Red Cross, take out the gas canister, open it and throw its contents into the cell through the lattice in the side wall. The lattice was pretty high, so he had had to climb a small ladder, here also with a mask on. After some time Mengele would announce that the people were not alive, phrasing it “It's over,” and together they drove off in the Red Cross van.

Moll then opened the gas chamber's door, and we would put on our masks and drag the bodies from the cells, through the narrow corridor, into the wardrobe and from there through a corridor to the furnaces. In the first corridor, next to the entry door, barbers would cut the hair, and in the second, dentists took out gold teeth. The bodies were put on metal stretchers mounted on wheels, and pushed into the furnace. The bodies were stacked in trios: two of them parallel, head to head, and the third arranged so the head rested on the latter's legs. By the time we put the third body in place, the bodies previously put inside the furnace were already on fire. I saw that due to the heat, the hands shrank and then the legs. All in all, we were in a rush, and could not see the entire cremation process. We had to hurry because of the lifting of limbs, which made it difficult for us to stack the third body in the right place. We used the stretchers in this manner: two prisoners would lift the end farther from the furnace, and one lifted the closer end. After the stretcher was guided into place, one prisoner would hold the bodies in place with a rake,and the other two would pull the stretcher from underneath them. After filling a furnace, we moved on to the next one.

Cremation took 15 to 20 minutes. Afterwards, we opened the furnaces' doors and filled them with more bodies. When the transports from Hungary arrived, we worked in two shifts in Crematorium 5, the day shift from 6:30 AM to 6:30 PM and night shift from 6:30 PM to 6:30 AM. This job lasted about three months, for the crematorium was not enough, and pits were dug next to it – three big ones and two smaller ones. The body cremation process was the same process used near Bunkers 1 and 2. Here, too, Moll was the cremator. The ashes were taken out in a similar fashion, crushed to dust in special containers and moved to the river. The crematoriums' ashes were first buried in special ditches, and later on, as the Red Army started attacking, Hoess, the commander of the camp, ordered the ashes to be dug out and moved to the Sola river.

The gas chambers in Crematorium 5 were approximately 2.25 meters high, for I couldn't touch the ceiling by reaching up with my hand. The ceiling stood about 25 inches above the doorway. The lower edge of the lattice through which the Zyklon gas was poured into the cell was within reach of an average man lifting his hand, but Steinmetz had a small ladder on which he climbed to reach the lattice. This was also done by other SS men in different periods, though I cannot recall their names. I do remember, however, Steinmetz's name, for at the beginning he was in charge of our Sonderkommando group. I cannot recall his first name. He was a medium-height man, shorter than me, a blonde of about 26. He always got Slovakian girls for various services. I know not in which language he spoke to them.

The supervisor of Crematoriums 4 and 5, along with Bunker 2, was Hauftscharfuhrer Moll. He was a fleshy, medium-height man, his blonde hair swept sideways. He had a false left eye, and his age was about 37. His wife, ten-year-old son and seven-year-old daughter lived in the town of Auschwitz.

Dr. Mengele, the camp doctor, was usually present during the poisoning. He was a tall man, with fair hair, about 40. He always arrived with the Red Cross van, in which the Zyklon gas was brought. All the group members saw that during the process he stood next to the gas chamber's door, which had a small lattice. After the poisoning, the door would open on his command. As the bodies were dragged out, he was already on his way in the notorious sanitary van. Never have I seen Mengele examining the people who were about to be slaughtered or the dead bodies.

At the beginning of May 1944, the killing and cremation of the Jews of Hungary began. The bodies of those who arrived in the first transports were cremated in crematorium 4 due to malfunctions in the furnaces of Crematorium 5. Until the end of the period, the Jews of Hungary were cremated in pits dug for this purpose near Crematorium 5. Five pits were dug, 25 yards long each, 6 yards wide and 3 yards deep. Around 5,000 people were cremated in those pits daily.

In accordance with the large numbers of people arriving each day, Bunker 2 was reactivated for the purpose of killing and cremating people. I know not how many people were cremated each day, for at the time I did not work near Bunker 2. All places then worked in two shifts, day and night. This labor was carried out through May and June of 1944. According to my calculations, during those two months about 300,000 people were cremated in Crematorium 5. Those people were rushed on foot straight from the railway station to Crematorium 5. Among them were men, women and children of various ages. When a transport arrived, we were locked in two small rooms intended for this purpose, so as to not come in contact with the transport people, so we would not be able to warn them of their impending fate. Nonetheless, it sometimes occured that a person would be too weak to walk by himself and then, supervised by an SS man, we were forced to take him to the Crematorium. On such occasions we used to talk, more than once, with the carried person. Most did not realize they were going to their death, nor would they believe us when we warned them. I remember that in 1943 about 70,000 Jews of Greek origin were slain, for at the time, Keller, the supervisor of Crematorium 2 and 3, told us that our “idling” days were over, because 70,000 people were due to arrive from Greece. He informed us thus because there was a perceived slowing in crematorium activity, and our work was easier. On matters of other nationalities I have no data, and cannot determine how many victims of each were annihilated in Auschwitz. It is my estimate, however, that over four million people were slain in the two bunkers and the four crematoriums. Other members of the Sonderkommando held the same view. The Kommando's secretary Grodowski, born in Grodno, maintained a list containing a record of the number of people killed and cremated, based on data received from prisoners who worked in the crematoriums, and according to prisoners' assessment through their labor. He was killed in the uprising of October 1944, when 500 prisoners of the Sonderkommando out of a total of 700 were shot to death. One hundred worked in Crematorium 2, one hundred more in Crematorium 3, and 500 in Crematorium 4. Grodowski's records were buried near Crematorium 2, in an area surrounded with barbed wire, where I dug them out and handed them to the Soviet Committee. Along with the numerical records was a letter addressed “To the finder,” translated to Hebrew by request of the committee by prisoner Dr. Gordon. The committee took the material with it. I also know that in the Crematorium 2 area more records and the deceaseds' papers are buried. There should be a search, for since the blowing up of the crematorium I can no longer find my exact bearings, because the explosion changed the area. I did not work in Crematoriums 2 and 3. Zissner and Mandelbaum were working there, and Tauber worked with me after being transferred from Crematorium 1 in Auschwitz to Brzezinka. The Sonderkommando was assembled mainly with Slovakians prior to December 1942, who were murdered in Crematorium 1 in Auschwitz. As I noted, my group included 200 men, and shortly afterwards 200 more joined. Later on 200 were sent to Lublin, and 20 Russians from there joined us. From them we learned that those 200 sent to Lublin were shot to death. In 1943, 200 Greek Jews joined, and in 1944, 500 from Hungary. In October most of the latter were murdered, 400 of them in the Crematorium 4 yard, and 100 more in a field near Crematorium 2. In the same month Moll selected 200 more prisoners and sent them to Auschwitz, as we had later learned from the “Kanada” group, whose job was to sort the dead's belongings, to be disinfected in a clothing disinfection warehouse. In November 1944 an additional 100 prisoners were sent, we were told, to Grossrosen Camp. They were sent on a punishment transport.

After all those reductions, the group remained at 100 prisoners. Crematorium 5 was active until the Germans' last days in the camp, after which it was blown up just prior to their fleeing. Near the end, only the dead and those murdered in the camp were cremated in the crematorium. There were no more poisonings. Thirty prisoners would then work in the crematorium and the rest, myself among them, worked in dismantling Crematorium 2 and 3. At the end of May, 1944 the group was moved from Block 11 in section B II D to Crematorium 4, in which I remained until October, 1944. As I mentioned, about 700 prisoners lived there. As the crematorium was overcrowded, and not so many workers were needed, we were ourselves afraid of extermination. We agreed upon an uprising, which was planned for a long time. We had contact with the outside world, we manufactured grenades, and we had arms and a camera. We waited for the third attack of the Red Army. We estimated that only under those conditions did we have a chance of success. We therefore agreed to put it off no more, and act. I do not recall the exact date, but it was a Saturday when we fell upon the SS guards, injuring 12 of them. There might have even been some casualties. During that time, the prisoners of Crematorium 2 were moved, and those of Crematorium 3 were unable to even begin the operation. An SS force immediately arrived at our crematorium, and several units took over the area, shot 500 prisoners, and only those who hid themselves were saved. I myself hid behind some timber, and Tauber hid inside the Crematorium 5 chimney. The rest of the survivors were moved to Crematorium 3. Our lives were spared so that we could be interrogated, but the questioning led nowhere, in spite of search parties and personal interrogations. Following the failure of the uprising we buried the materials, especially the grenades, and stopped the underground actions.

I lived in Crematorium 3 until November 1944, when I was moved with my group to B 11 D camp. I was in Block 3. From October, the time of the uprising I mentioned, I worked in dismantling the crematorium, mainly Crematorium 4, which was burned in the uprising, so we worked on dismantling the walls. The metal parts were sent to Auschwitz, where they remained in storage. Other prisoners were dismantling Crematorium 2 and 3. Their dismantling began on November 1944, and we were told they would be sent to Grossrosen Camp. Metal parts, doors, ventilation equipment, benches, stairwells and various parts were in storage. Note that the doors and window covers in Bunkers 1 and 2 were of the same manufacture as in Crematorium 4 and 5. They were made of heavy wood, thick and insulated with felt in the grooves. The doors were shut with double metal handles, and for perfect sealing, bolted shut. All doors leading to gas chambers had small glass windows in them. In Crematorium 2 and 3 there were no covers, for the openings in the gas chambers were in the ceiling, and were sealed by concrete covers. Enclosed are the drawings of Bunkers 1 and 2, and of Crematorium 5, which was identical to No. 4.

I remained in Block 13 in section B II D untill the beginning of January, 1945. We were moved to Block 16, from which, on January 18th, we were sent towards the Reich. We marched on foot, and near Pszczyna, Tauber and myself were able to slip away from the marching lines. With me, all of the Sonderkommando group, over 100 men in all, were marching. Only a few survived. In the last days, Mazze Van-Klive returned from Holland and without delay went back to his own country. Among those who left Auschwitz were Zabeck Chazhan of Gostynin, Shmuel of France, Leibel of Grodno, Llemke of Skarbanowo, David Nanzel of Rypin, Moshe and Yankel Veingarten of Poland, Sender of Berlin, Moritz of Greece, my brother Avraham Dragon from Zuromin, Poland, Serje of France (the block veteran), Abba of Grodno, Becker Baruch of Luna, Kuzzin of Radom and many others, whose names I cannot remember. It is my intention to return to Zuromin and resume my occupation. I hope my brother shall also return, so that we will work together. I am looking forward to enlisting in the army. After what I have been through I am tired and weak, and would like to lead a normal life, disengage myself from the camp atmosphere and let all the trouble I have been through be forgotten.

Justice: Ian Sehn

Witness: Shlomo Dragon

Prosecutor: Eduard Pechelsky

Reported by: Christina Shymanska

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Zuromin, Poland

Zuromin, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 29 Feb 2008 by LA