[Page 54]

Before World War I

Yitschak Rokhel (Tel Aviv)

Who will uncover your ruins, Kremenets, my hometown?

After the Holocaust that befell us, I decided to write a few lines about life in our city during my childhood in memoriam.

A View of the City and Its Surroundings

Kremenets lies in the southwestern part of Vohlin province, in a valley surrounded by mountains that are a part of the Carpathians. Being the district's center, the city oversaw the many villages and townships in its district. Before the war, the population numbered about 30,0000 people, 10,000–12,000 of them being Jews, but the non-Jewish residents – Ukrainian, Russian, and Polish – lived mostly on the outskirts of town and in the mountains, while the Jews lived in town and in the two suburbs – the Dubna suburb and the Vishnovits suburb. So when a visitor came to town, he received the impression that the majority of the residents were Jewish. And in fact, in the city's central streets lived a never-ending, congested Jewish population, while the houses were ethnically mixed in the side streets: a Jewish one next to a Russian or Polish one.

[Translation Editor's Note: The text describes Dubna and Vishnevets as suburbs, but they are actually towns.]

A large area of the town was taken up by the seminary for priests, its gigantic buildings and large grove reaching the foot of Mount Vidomka. To a certain extent, this institution had vested the town with a Christian-religious quality. The second educational institution, which was also in a large grove at the foot of the mountain, was the High School of Commerce, where more than half the students were Jews.

The town itself was narrow and long, with one long street dividing it from one edge to the other from the Vishnovits suburb through the center of town and the Dubna suburb, all the way to the railroad station. Although the street was quite narrow, it was called “Sheroka [Broad] Street.” Side streets and alleys that stretched from it twisted and interwove all the way into and through the mountains. Mount Bona, the highest of the mountains surrounding the town, afforded a panoramic view of the whole town. Its history was cloaked in assorted folktales about the castle that had been built there and the deep pit at its summit. The Jews called it “the Pit of the Condemned to Death,” where, according to traditional tales, castle soldiers who committed a crime and were sentenced to death were buried. During our time, this mountain was used as a lookout for fires; a scout walked day and night on the turret at its peak, and if he spotted a fire, he would blow the trumpet to alert the firefighters.

The mountain was connected to the town by a paved road, which was used for leisurely walks during the Sabbath and holidays. Across from it Mount Vidomka spread wide, with its groves and with vacation cottages built on its slopes and in its crevices. The Zionist young people used to assemble in those groves on the Sabbath, and during the revolution it sheltered most of their illegal meetings. Other famous mountains were the Mountain of the Cross (Krestova), because of the cross at its peak, and the Mountain of the Virgins. This mountainous area left its stamp on the life of the town and the character of the residents.

There was no river in town, but a narrow and turbid stream, which wound its way to the foot of Mount Bona, flowed full of water in winter and dried up in summer. The residents called it Potok, and the Jews called it Potik. When a divorce decree was issued, it would read, “issued in the town on the River Potik.”

[Page 55]

There were 12 subdistricts in the Kremenets District: (1) Radzivilov, (2) Berezits, (3) Bialokrinitsi, (4) Pochiyuv, (5) Vishnivits, (6) Shumsk, (7) Vishgorodok, (8) Lanovits, (9) Bialozorki, (10) Yampol, (11) Katerburg, and (12) Aleksinets.

[Translation Editor's Note: Many of these subdistricts currently are known by other names. The following list conforms to the names approved for use by the U.S. Board of Geographic Names. They are in the same order as the names given above: (1) Radyvyliv, (2) Velikiye Berezhtsy, (3) Belaya Krinitsa, (4) Pochayev, (5) Vishnevets, (6) Shums'k, (7) Vyshgorodok, (8) Lanivtsi, (9) Belozerka, (10) Yampil', (11) Katerinovka, and (12) Staryy Aleksinets. For their locations, see the Town Locator.]

Economic Life

How did the Jews of Kremenets earn their living? No statistical research has been done on this, so this review is general.

The area was mostly agricultural and had a market day (fair) every Sunday, when many of area's non-Jewish farmers would come to barter and shop with the townspeople. Most commerce at every stage (retail, wholesale, stores, and peddlers) and in all sorts of products (grain, lumber, iron, cloth, groceries, cattle, horses, etc.) was in Jewish hands. About half of the city's Jews were involved in business, about 20% as professional craftsmen and laborers. They were in only certain kinds of crafts, and no Jews practiced others; there were no Jewish stone masons or builders, or even plasterers. In contrast, there were many Jewish tailors, shoemakers, carpenters, woodcarvers, tinsmiths, seamstresses, and bakers, and Jews supplied all the town's transportation for people and merchandise as well as porters.

Except for one large foundry, owned by Jews and employing non-Jewish laborers, industry in Kremenets was not modern. A factory for matches lasted only a few years, and near town, by the village of Bialokrinitsi, a factory for fired bricks was owned by Jews, but the laborers were non-Jews; it was originally built to accommodate the construction of the army barracks in the vicinity.

Ours was not a large commercial town. It served only the area within the district and its needs. We did not have people with great wealth in Kremenets, but neither did we have extreme poverty. It was a town where people made a living, and generally the Jews had an economic base in it. The district did not have industrial plants either, except for those directly tied to agriculture, such as flour mills and distilleries. These were owned by the estates and leased to Jews, as were the fishing rights for the rivers.

Public Life

How did Jewish community life in Kremenets look in the period before World War I? The community was not well ordered and organized, but it did have a few public institutions with hardworking and devoted civic activists. The following are worth mentioning:

A. Care for the Sick (also called Hekdesh) – a public hospital intended for the poor, containing about 30 beds. Physicians volunteered their services, and the needy were treated for a minimal fee or none at all. In the last few years, this institution received a building of its own, and the two Jewish physicians in town, Drs. Landsberg and Litvak, worked there. Mikhael Shumski, Yisrael Margalit, and others were active in that institution for a very long time.

[Page 56]

B. Talmud Torah – This Orthodox school, intended for the children of the poor only, had its up and down periods. For a long time it was run by R' Duvid Leyb Segal, the son-in-law of the previous rabbi, R' Velvele. R' Moshe Rokhel, a wealthy Orthodox merchant, invested much effort in this institution and succeeded in strengthening it economically.

The affairs of the rabbis, ritual slaughterers, synagogues, and Burial Society occupied an important place in community life. The same was true of vigorous public activity in various public arenas, such as charitable concerns, acts of loving-kindness, anonymous donations, supporting the sick, the Free Lodging Society, hospitality, and the like.

The atmosphere of volunteerism among the townspeople when it came to community affairs and charities should be noted. A “rebbe” (“a good Jew”) who came to town for a few days would never leave empty-handed. He was given donations generously.

Volunteerism and Civic Activists

Emissaries from distant yeshivas in Lithuania used to come to town to collect donations. At times, a particular public project would excite the town and bring a wave of volunteering with it. I remember when the new bathhouse was to be built; a few donations were for the sum of 1,000 rubles each. During the dispute over the rabbis, each side made sure his rabbi was well taken care of. Here is an episode that illustrates the spirit that lived within the hearts of the best civic activists. One day, a new district governor, known to be impeccably honest, was installed in our town. When two civic activists of his acquaintance mentioned during a conversation that he was dishonoring the town by driving an old carriage, he explained to them that a government employee who does not accept bribes and cannot afford a stately carriage is unable to purchase one. Daringly, they offered to buy him a new carriage as a gift. After vacillating, he finally agreed to accept the carriage as a token of friendship on the part of the Jewish community. But, he added, from then on he would not veer from his habit and would not take bribes. When the two community representatives left him, one suggested taking up a collection from the wealthy members to buy the carriage, but the other said, “God forbid! You and I will give him the carriage out of our own money.” They did so, and without publicity, so as not to cause problems, presented the carriage in the name of the community. This helped establish good relations between the governor and the town's Jews.

The community representatives chosen to deal with the authorities came mainly from assimilated circles, whose language was Russian, and in everyday life they associated with Russian society and the government office staff. Of these representatives, Mikhael Shumski and Yisrael Margalit stood out. They usually functioned together, so much so that the townspeople tended to mention their names in one breath. Both were members of the City Council and were generally considered expert Jewish representatives in dealing with the authorities, though no one could tell for sure if or when they had elected for this task or whether circumstances had put them there. They were also among the founders of the High School of Commerce and members of its supervisory committee for many years. Those connections took the character of intercession in personal matters and communal affairs through the use of personal influence and gifts. From time to time, certain members of the religious circles whose personal standing, strong character, and wealth had trained them for it would join the negotiations with the authorities.

The Story of the Dispute

A bitter dispute about the rabbis in our town lasted for nearly ten years. Rabbi Velvele (his family name was Mishne) from the town of Zvihil held the rabbinical chair of the Kremenets community for 25 years – from 1880 until his death in 1905.

[Page 57]

|

|

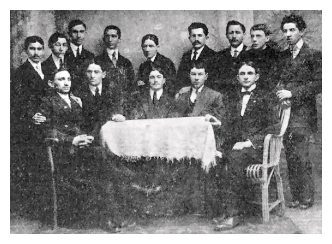

Figure 8. Group from the Young Zion Society, 1912

(Right to left) sitting: (1) Avraham Biberman, (2) Yeshayahu Bilohuz, (3) … [unknown] (4) Moshe Biberman, (5) Chanokh Hokhgelernter.

Standing: (1) Yeshayahu Katz, (2) Yakov Broytman, (3) Goldenberg, (4) Aleksander Rozental, (5) Okun, (6) Yitschak Rokhel, (7) Yisrael Biberman, (8) Chanokh Kesler, (9) Moshe Yampol. |

He was a learned and God-fearing man, but hot-tempered and quick to anger. He never showed favoritism toward people of important standing in the community, and because of that, he was unpopular among civic activists. When his son-in-law, R' Duvid Leyb Segal, settled in our town, he made an effort to remove pivotal institutions – Care for the Sick, Talmud Torah, and others – from the influence of the town's civic activists and put them under the rabbi's sphere of influence. As long as R' Velvele was alive, the opposition remained restrained, but the community's activists kept their resentment inside. After his death, a group of his close associates brought Rabbi Senderovits from Piotrkov to town. With this choice, they intended to continue the rabbi's influence on the town's affairs. Another group of influential civic activists, who were opposed to this choice, brought a rabbi of their own choice to town, R' Yitschak Heler from the town of Kurilovits. For about ten years, the discord between the supporters of each rabbi continued. With it came many negative side effects: defamation of the opposite rabbi, his expertise in the Torah, and his authority, subversion, slander, disruptions in the reading on the Sabbath, divisions in the synagogue, the establishment of new synagogues, and even fights. But to their credit, it should be noted that tale-bearing and slander were never brought to the authorities, though in general our town's hands were not clean of this offense.

The discordant chapter is a sorry one in the late period of our town's life. It brought on a deep division and unwarranted hatred, as a result detracting attention from the community's essential affairs. It is fair to assume that the ones to suffer most from the discord were the two rabbis, and it is possible that they did not even get involved in it at all, even if they could not stop it.

Both were great scholars; one of them, Rabbi Heler, had authored few books of Responsa: Isaac Acceded, The Offering of Isaac, and others.

[Translator's Note: In Hebrew, Isaac Acceded is Vayater Yitschak, and The Offering of Isaac is Minchat Yitschak.]

[Page 58]

I still remember today the sermon given by the rabbi from Kurilovits at my bar mitzvah. The subject was “Tefillin for the Head and Tefillin That Is in the Head.”

At the head of the opposing factions were Aba Tsukerman, supporter of the rabbi from Piotrkov, and Hirsh Mendil Rokhel, supporter of the rabbi from Kurilovits. During the war years, the discord dissipated. The rabbi from Kurilovits left town with the flow of refugees and settled in Odessa.

Torah and Fear of God

Was our town a place of distinguished scholars who were erudite in the Torah? Not in particular. It could be said that the town was graced with an “average character”: it had no extremely wealthy people and no wretchedly poor ones, but was a town consisting of people who earned a living. There was no fanatic Hasidim and no sharp Mitnagdim, but mutual tolerance between them. There were neither extremely religious people nor converts. The same thing was true in relation to “scholarship”: there were not many distinguished, erudite scholars, but complete ignoramuses and illiterates were almost nonexistent. Most Jews knew the Torah – how to read portions of the Pentateuch with Rashi's commentaries. Between the afternoon and evening prayers, they would study a chapter in the Mishna and sometimes a page of Gemara. In the synagogues and study hall, permanent study groups mainly studied the Mishna and Ein Yakov. From time to time, in honor of finishing a section, they would celebrate with a glass of brandy and cakes. True, there were a few distinguished scholars like the venerable R' Shlome Alinkis the Gemara teacher, R' Chayim Leyb Volf, and the sharpest of them, R' Moshe Velis, who served as a permanent arbitrator in money problems because of his great astuteness. There was no yeshiva in our town, so those few who desired to do yeshiva study had to travel to other towns – to yeshivas in Lithuania. For a few years, a small yeshiva existed in our town, run by a head of yeshiva who had moved to our town from Zvihil. One of the prodigies that he brought with him was Avraham Ikar, a member of the Second Immigration and the Haganah.

[Translation Editor's Note: Ein Yakov is a compilation of stories from the Talmud.]

Most of our people were religious, and few were freethinkers. The general atmosphere in town was imbued with devotion to tradition; during the Sabbath, all the stores were closed, work stopped, and the synagogues were filled with worshipers, and the effect of the holidays was very obvious. People did not drive on the Sabbath, and those who breached the rules did so out of sight, not daring to enter the town in a vehicle. Most old and middle-aged men wore kapotas, especially on the Sabbath and holidays. Most men of the young generation shaved their beards and walked in public with their heads uncovered, and some spoke Russian. But as the saying goes, “Even the sinners of Israel are full of good deeds, like a pomegranate,” for the truth is that members of the young generation were deeply embedded in Jewish traditions, and to “honor thy father” they would come to the synagogue on the Sabbath and holidays, keep kosher, and follow the other ways of Judaism. The High School of Commerce had a destructive influence on traditional ways, as its students had profaned the Sabbath since their youth and instilled this habit in their parents' homes and everyone around them. A second reason for the breaking of rules and traditions was the revolutionary movement, which swept up a considerable number of the town's young people. The World War speeded up the process of secularization.

[Translator's Note: The kapota is a long coat, generally black.]

Relations between Peoples

Because the law forbade the Jews to settle in villages, few settled in the villages in the vicinity of Kremenets. In the townships and the city itself, the Jews were a considerable part of the population, and their effect was bigger than their numbers. It should be noted that the Jew did not see himself as a “temporary visitor” but as a citizen involved and rooted in a country with an ethnically mixed population. And this was also how the other ethnic peoples saw the Jews. Certainly, anti-Semitic propaganda was carried out, and here and there it also bore fruit, but in day-to-day life, hatred of the Jews was not seen. In daily life, their treatment was completely proper. Our city and its surrounding area did not experience pogroms (though during the days of Petliura, there were some isolated cases of murders of village Jews).

[Page 59]

As opposed to this, the Jews were discriminated against when it came to the law, and they had no part in city and government administration. For that reason, every government action was received as a decree that had to be overcome through lobbying, bribery, and such.

Reciprocal contacts among different ethnic groups occurred mainly for work and business purposes, and they were only minimally ties for mutual cultural and public activities. Wealthy merchants and members of the intelligentsia, who spoke Russian, saw it as an honor to be members of the public club called “the high-society salon,” where they enjoyed their evenings playing cards and dominos in the company of Russian intelligentsia and officials. There were other means of cultural association and close relations, but in general it has to be stated (that is, for the period before World War I) that the Jewish community in Kremenets formed a tightly knit, unified, independent entity – it had a way of life of its own, including a pronounced national folklore with all its light and shadows. And Jews were largely immune from assimilation into the other ethnic groups that formed the majority in the area. The fact is, mixed marriages or conversions were very rare.

Status of the Zionist Movement

What was the status of the Zionist movement in our city? The attitude of most people from our city was one of indifference and dismissal, while a considerable number were openly opposed to it. The average person – a merchant and craftsman who saw himself as a wise and practical man – looked at the handful of adolescent and adult Zionists and saw a bunch of impractical idlers. In the days of public awakening, as in the 1917 revolution or during general elections, public sympathy seemed to be with the Zionist movement, but as soon as the wave of excitement dissipated, the Zionist Organization was pushed back into a corner, and the practical man went back to his business.

From time to time, a Zionist preacher would visit our city (Preacher Berker, father of Kariti of Kiryat Anavim, is remembered favorably) to preach to the public in the study halls between the afternoon and evening services. And it would seem that he had awakened dormant sentiments toward Zion and its new life. The community leaders, whether they were religious or freethinking, were not Zionist adherents. The religious ones opposed the basic idea because of dechikat hakets, and some did not approve of meetings where men and women attended together, sat with their heads uncovered, and spoke Russian. It is true that, in the early period, many of the talks during Zionist meetings were in Russian, even though most Zionists were members of the middle classes. In the eyes of the religious ones, the Zionist movement equaled heresy. Later, the situation changed. In 1920, the Young Zionists and Jewish Social Democratic Workers Party were active in Kremenets in addition to the veteran Zionists, and a group of pioneers immigrated to Israel. Early 1921 saw the Zionist Organization fighting to gain a leading position in the city's public institutions. Gathered around them were young people – mostly children of community notables and some from different circles – and a few adults. At that time, there was no clear difference between the Zionist factions; the Young Zionists, a fellowship without a clear program, were an active and lively part of the Zionist Organization, a sort of “youth guard.” As for the adults, although they were few in number, they were deeply rooted in their belief in Zionism and steadfast in their ideas. Each of them had an influential personality and was well known in the community: Dr. B. Landsberg, Yakov Shafir, Meir Goldring, Aharon-Shimon Shpal, Moshe Eydelman, Getsi Klorfayn, Aharon Fridman, Munye Dobromil, Meshulam Katz, and some other personalities – civic activists who paved the way for widespread cultural and Zionist activity in the period between the two wars and prepared for a large-scale pioneer immigration.

[Translator's Notes: Dechikat hakets refers to the concept of forcing the issue of the messiah's arrival by returning and rebuilding the homeland of Israel before the messiah's arrival. Young Zionists is Tseirey Tsion in Hebrew.]

[Page 60]

Education

Where in our city were Jewish children educated? Here, too, precise numbers are missing. It is reasonable to assume that about half the boys were educated in the cheders, and the rest in other schools. Also, when they grew up, those who studied in a cheder for few years went to a Jewish or mixed school. It should be noted that Kremenets had dozens of cheders, each with 20–40 pupils. There were three schools in town where the language of instruction was Russian: a Jewish primary school, a city (primary) school for Jews and non-Jews, and the High School of Commerce. For some time, there was a private high school for Jewish and non-Jewish girls that belonged to Mrs. Aleksina. It is estimated that about 500–600 children were educated in those institutions. The two primary schools drew middle-class children, and children of the wealthy attended the High School of Commerce, due to the high tuition and long years of study. A good number of this school's graduates went away to large cities for higher education: to Kiev, Odessa, Petersburg, and Moscow. When they graduated, some became physicians and settled in different towns, but only a few returned and found a place in their hometown.

How Kremenets Was Saved from the Riots

Akiva Ziger (Haifa)

It was right after World War I. Russia was still embroiled in the revolution. From day to day, whole regions found themselves under different governments. This happened to Kremenets, too. Here Petliura's gangs ruled, and the roads to Kremenets were already overflowing with the Polish army. Petliura's men abandoned the town, which was left without rule of law or government protection, and immediately gangs of farmers from the area got together with insurgent townspeople and schemed to slaughter the Jewish population. The Polish estate owner Visotski, who was in town, heard about this and immediately joined the gangs as a leader and commander, telling them to get ready to land a mortal blow on the “Zhids.” He assembled all of them in the Lyceum and told them that the following morning they would sweep throughout the town and destroy it completely. In the dark of night, Visotski went to the Dubna road, where the Polish army was awaiting him. Secretly, he led them in, and thus the murderers' scheme was thwarted. My father, of blessed memory, told me later that Kremenets had been saved thanks to the blessing received from a visiting rabbi. The fact is that Kremenets came out of World War I without damage. But this time, even the rabbi's blessing did not help … annihilation came upon it, together with the rest of the holy communities.

[Page 61]

Help for Refugees during World War I

Menachem Goldgart (Tel Aviv)

Close to the beginning of the war, the Russian-Austrian front stretched near the shores of the River Ikva, about six kilometers from Kremenets, for a long period. But in the summer of 1915, General Brusilov opened a big offensive on Galicia, and within a few days the front shifted westward. During this move, quite a few cities and towns in the area were completely destroyed, and a stream of Jewish refugees began to flow into Kremenets from Radzivilov, Kozin, Pochayev, and other places. The wealthy families had left town earlier. But the poor came walking into Kremenets empty-handed; all their properties and houses had gone up in flames, and they had escaped to save themselves after many were killed during the battles, and many injured came with them. It was only 35 kilometers from Radzivilov to Kremenets, but it took the refugees weeks to arrive, hiding in the forests during the day and walking at night.

As soon as the community heard the news about the approaching refugees, community activists and workers set up a committee to help them (Aleksander Frishberg, Dr. Arye Landsberg, Yitschak Poltorek, Mrs. Perlmuter, and others), and young people from the refugees joined them. The main concern was feeding the people, even before their arrival in town. The committee appealed to the Red Cross, which sent field kitchens to the forests where the refugees were roaming. The provisions were handed over to the committee, which oversaw the distribution of kosher food. About 3,000 refugees came from Radzivilov alone, and with those from other towns, the number swelled to about 5,000. Meanwhile, the need for shelter was being taken care of. As soon as the refugees arrived in town, they were placed in buildings of assorted community institutions, private homes, with relatives, and other places. The Talmud Torah building, which had previously been used as horse stables by the Russian army and was a semiruin by now, was the main shelter. It was very crowded, with 10 people per windowless, doorless room. The Christian seminary buildings could easily have housed most of the refugees, but the buildings stayed empty, as they were not offered of use. The Red Cross kitchen, however, was allowed to set up in the seminary's spacious yard.

A few dozen of the city's young people, mainly from Zionist movements, established a group to help the refugees, for some reason calling itself the Market Statistics Council, and at its head stood the young and enthusiastic Bozye Landsberg. In reality, this council took on the responsibility of caring for the refugees, developing effective, extensive activities in many fields, and thanks to their devotion, physical and emotional degeneration was avoided. The first thing they did was to create a detailed list of the refugees according to Red Cross regulations (the name of the council came from this task). They set up real legal aid, seeing to identity documents and the like. Financing for the assistance came from three large organizations that worked in the field in Russia at that time: the Red Cross, the United Councils of Cities, and the United Zemstvos. An oversight board made up of representatives from the three organizations was formed, and the youth council worked with them as their implementation group.

[Translator's Note: Zemstvos refers to an elective council responsible for the local administration of a provincial district in czarist Russia.]

The kitchen that opened for the refugees in the seminary yard, which was run by the young volunteers, supplied three meals a day for more than 3,000 people. As the products received from the Red Cross were insufficient, the volunteers solicited money from other sources and improved on the food given to the needy.

[Page 62]

|

|

Figure 9. Youth Committee for Refugee Aid, 1916

Sitting, right to left: (1) Vayser, (2) … ? (3) M. Goldgart, (4) … ? (5) Sonye Landsberg-Poltorek.

Standing, first row: (1) Balter, (2) … ?, 3) … ?, (4) Zamberg, (5) Sonye Perlmuter, (6) … ?

Standing, second row: (1) Yitschak Eydelman, (2) Dr. Binyamin Landsberg, (3) Bazdizhski, (4) … ? |

The towns from which the refugees came were almost completely destroyed, but some had saved a few possessions were in underground cellars. After much effort and persuasion, we rented 100 wagons from local farmers and, in a large caravan, went to Radzivilov to collect what was left of the possessions. At that time, the czarist regime suspected that Jews were spies for the enemy, so they allowed only two Jews to accompany the caravan: Mr. Barats and this writer. Endangering their lives, they managed to rescue the possessions that had not been burned, particularly clothing, and bring it to town. It was put in communal storage, from which it was distributed among the refugees.

Because of the general situation in the city, it was not possible to provide jobs for the refugees, so some of them eventually moved to other places in Ukraine and Russia. However, the majority stayed in our city and needed public support and care for a long period.

A special branch of the youth council made sure the children of the refugees received an education. Temporary schools were formed in which some of the young volunteers served as teachers. Eventually, those temporary institutions became permanent, regular schools, where children from the town were educated together with the refugees' children. Much effort, enthusiasm, and endless devotion were invested in this generous and blessed project. Thousands were saved from starvation. Many young people, who with the fervor of youth were carried away with this work, found that it was the way to the masses of the nation. Later, some of them became good social workers, educators, and community activists.

[Page 63]

At the Beginning of the Revolution

M. Kornits (Jerusalem)

It is February 27, 1917, an ordinary winter day with no discernible changes. Life continues in its routine tracks as in days past. The train has not arrived, nor have the newspapers. Even when they arrive in an hour or two, will you find the echoes of today's happenings in them? They are published in Kiev or Moscow or Petersburg two days ago. Suddenly, an unusual movement is felt in town. Here and there a group of people forms in the streets, excited discussions begin, and in moments the whole town knows that a revolution has begun in Petersburg, the Czar has abdicated, and a temporary government has been elected under Kerensky's leadership.

Is that believable? Finally, even we, the Jews, would not be singled out for discrimination, but we would be citizens with equal rights like the rest of Russia's nations. Joy and merriment! Every face is radiant. The masses streamed to the Great Synagogue for a public meeting. Young members of the freedom movement came out with exciting speeches. The gathering thousands decided to elect a Jewish Community Council, and on the spot the young people elected young Fritz Eydis as head of the community. Later it was seen that this was a hasty move … the era demanded the injection of young blood into community life. After some time, a Community Council of representatives from different political factions was elected, and I was chosen as the council secretary. The members worked on a voluntary basis, each willingly donating his time and efforts on behalf of our town's Jewish community.

Until that time, the authorities had appointed the members of the City Council, and under the Czarist regime the council had included Christians and only one Jew. This was M. D. Shumski. As it happened, the city fathers never considered the needs of the Jewish population, and more than once Mr. Shumski had to take on the battle single-handed. Although he fought his war with wisdom and dedication, he never succeeded. Jews comprised about 40% of the 30,000 residents of our town. We then decided to bring about a drastic change in the ratio of power and representation in the City Council. When a new law governing elections to the City Council was announced, we started a fierce campaign and successfully elected a City Council of which 50% of the members were Jews from different circles and factions. These were M. D. Shumski, Avraham Verthaym, Meir Goldring, Moshe Eydis, M. Sturozh, Konya Segal, Sh. Fingerhut, Krozman, and this writer.

After the election of a new mayor, the City Council, and its assorted committees, we set a goal for ourselves: to improve the poor conditions of our public institutions, such as the hospital, the home for the aged, the Talmud Torah, etc., as soon as possible. Municipal offices, which had not previously employed Jewish clerks – even though about 75% of the levied taxes came from the Jewish population – now employed quite a few. The situation with regard to supplies in the city was quite serious; these were days of shortage and scarcity of flour, sugar, salt, fuel, soap, etc. At one of the City Council meetings, it was decided to establish a supply department, with Meir Goldring at its head and me as his assistant. After many negotiations and much travel to the county seat of Zhitomir, we managed to acquire essential consumer goods. City stores were opened and supplies were distributed according to ration cards. Slowly, day by day, matters were brought up to acceptable levels, but then the political situation worsened and, with it, economic conditions. A separatism movement began in Ukraine, and thanks to encouragement from the Germans, it yielded fruit in a short time. Ukraine declared itself an independent country, and Skoropadski was declared the head of free Ukraine.

[Page 64]

The regime's “fist-and-whip” policy was felt most strongly among the Jews. The beating and arrest of the progressive members of city councils and public institutions began. In our town, Bozye Landsberg, Fritz Eydis, the Ukrainian socialist Koval, the pitiable Tsiperfin (the poor man was so depressed by his arrest that he died shortly after his release), and I were arrested and jailed. Meir Goldring managed to escape arrest at the last moment. We were kept in jail without investigation or trial for 99 days until our release. A few days before that, we had declared a hunger strike and demanded that each of us be given a notice of charges. This was denied, and instead, the warden in charge, a veteran clerk from the czarist days, came to our cell (we were all incarcerated in the same cell), and addressed us as follows:

“Gentlemen, please stop this hunger strike. Tell me what you want for the evening meal, and I'll order a samovar heated for you immediately and send someone to buy fresh sausage and white bread. This jailhouse is the best place for you; if you were free now, who knows how many of you would still be alive .…” Indeed, his words were almost true; waves of rioters ran all over Ukraine rampaging against the Jews. But we did not stop our hunger strike until the next day, after we received a secret note from a young Jew not to worry, that on the next day he would be arriving at the head of a detachment from Petliura's army and would free the city. And so it was. The young man came riding on a white horse, conquered the town, and sent his soldiers to release us. When the gate opened and we saw who was releasing us, we preferred to stay in our jail cell, so terrible did our saviors seem to us. Eventually, we left the jail and dispersed, each to his home.

We had spent hardly a few days at home when new trouble arrived: the Petliurans had been chased away, and new rulers arrived. More correctly, chaos reigned and there was no rule. The Bolsheviks came, stayed a few days in town, “purified” the bourgeois a little, and went away. Rumors spread that the Polish armies were nearing the city, but until they did, our town suffered a few hours of horror.

The farmers from Shumsk and nearby villages found out that the city of Kremenets had left abandoned without anyone in charge, and they decided to “take the law into their own hands.” The gang arrived in town with sacks on their backs, because their leaders had promised them that they would be given permission to ransack and loot the Jewish population to their heart's content. Visotski, who had previously been an officer in the Czarist army and was in town at that time, saved the community from a total pogrom. He succeeded in approaching the Polish army posts and getting them to hasten their entrance to the city. On their arrival, the Shumsk gang escaped with their lives. This reign, too, was short-lived; the Poles retreated under pressure from Marshal Budyoni's troops. Again the authorities changed, and our city went from hand to hand until the Bolshevist army retreated from the Warsaw vicinity, and the Poles recaptured our town and ruled it until September of 1939.

Many hardships were visited on Kremenets in 1917–1918, but the town's Jewish representatives guarded the interests of its residents in spite of all the vagaries of the time.

[Page 65]

During the Changes of 1917–1920

Azriel Goren (Gorengut, Pardes-Chana)

When the Kerensky government was established, I moved from my hometown, Yampol, to Kremenets, where I served as a rabbi. This was a short honeymoon period for the Russian intelligentsia in general and Jews in particular. With the declaration of equal rights for all minorities in Russia and abolition of the special restrictive laws that had oppressed the Jews for generations, a wave of excitement flooded the Jewish section of Kremenets, too. In national and communal work, our national intelligentsia in particular excelled. At its head stood the distinguished B. Landsberg, a high school classmate of the president of the Kneset, Yosef Shprintsak, may he live long.

This activity focused on three aspects: (1) preparation for immigration to Israel, (2) cultural activities, and (3) attainment of equal rights for Jews in law and in practice.

The first immigration group was established in those days, but because of all the political entanglements, immigration was postponed for a year and a half. In the city's two high schools, for boys and for girls, the study of Bible and the history of Israel (which I was teaching) were added to the curriculum. Lectures on the history of Zionism and the culture of Israel deepened our young people's national consciousness.

Five representatives of the Kremenets Jewish community were elected to the Kremenets City Council, headed by the liberal and likeable Judge Pokrovski. For the first time, the Jewish community became organized into an intrinsically autonomous national framework, which kept a constant link with the Center for Jewish Communities in Petersburg.

The excitement and elation lasted just a few months; our achievements in the life of the country's renewal and in local authority were large and important – and then heavy blows landed on our heads from the national movement led by Petliura. The situation worsened with the disintegration of the Russian army. Every day Ukrainian and Russian deserters showed up in town, extorting, robbing, and terrorizing. How could the police use weapons against hungry and embittered soldiers? The atmosphere was permeated with dread and horror, particularly in the Jewish section. In one of the alleys, a young Jew was killed after refusing to take off his shoes and hand them over to an extorting deserter.

It is hard to bring up memories from our youth; our feelings seem to be similar to those of an amputee who feels pain in an amputated foot ….

Editor's Note: The era of Polish governance, 1920–1939, is covered extensively in the next sections: “Public Life,” “Education and Culture,” and “Zionism and Immigration.”

[Page 66]

Twenty-One Months under Soviet Rule

Ayzik Hofman (Tel Aviv)

English Translation by David Dubin

On September 10, 1939, the Polish government and its diplomatic corps escaped from Warsaw through Kremenets-Zbaraz-Zaleshchiki on their way to Romania. On their way, they stopped in Kremenets for three or four days and stayed in the Lyceum and hotels. The city had never witnessed such regal pomp, fancy cars, and consular representatives of foreign countries with their flags and symbols as were seen in those few days. Of all the countries' representatives, apparently only the Italian and USSR delegates been forewarned of the coming bombardment and left in time, while the rest of the diplomats stayed.

The next morning, the city was bombed; it was market day, and hundreds of people were killed in this surprise attack, which was aimed at striking the government and causing confusion among the citizenry. Many people left their homes to hide in the mountains and forests. Some returned at night, while others stayed and slept in the open. This one shelling was sufficient to paralyze the life of the city.

On September 17, the citizens listened to Radio Moscow announce the agreement between Russia and Nazi Germany. People left their hiding places and awaited the arrival of the Russians. Some wealthy people and landowners escaped to Poland and Germany, but none of the Jews left. When the Red Army arrived on the 22nd, it was received cheerfully.

The mayor and the Polish police were ready to help the new regime keep order; a “temporary administration” was formed immediately – under the authority of the Russian army and politicians – to which were added some local clerks from the Jewish intelligentsia and Communists who had been released from jail and returned to Kremenets.

In general, the new regime showed a tendency to favor the Jews, who were an intellectual and devoted element, while many of the Poles were members of nationalist movements. During the early months of Soviet rule, the Jewish population swelled by 5,000–8,000, including refugees from western Galicia and Congress Poland, escapees from the Nazis, returning students, and those from the city who had been living out of town temporarily. The tendency for families to reunite was growing stronger. Some newcomers were absorbed into the government administration, and others young Jews with a technical education, who had been denied the opportunity to work in their profession because of the Polish oppression and had been forced to go into commerce, were now able to pursue their professions.

Rapidly, all the economic institutions prevalent in Russia were established: a national commerce network, including national companies to utilize forests and buy agricultural products and supplies. Industrial cooperatives, such as a large one for shoes, were formed. Coal and peat mines that had not operated during the Polish regime were rehabilitated and employed many workers and clerks. In those enterprises, refugees who did not know Russian found work as laborers.

In those days, the saying was that all three nations living in Vohlin were satisfied during the Soviet regime: Jews received jobs in offices, Poles were permitted to deal in secondhand clothes (before then, they were jealous of the Jews, who had a monopoly in this), and Ukrainians were permitted to have signs in Ukrainian (the official language in the government offices was Russian only).

[Page 67]

Until January 1940, economic life continued in an orderly fashion; commerce was free, and products were sold in stores according to the ruble-gulden exchange. Quite soon it became evident that stocks would not be replenished, resulting in rising prices. The delivery of supplies was irregular, and when sugar or manufactured goods arrived in the government stores, long lines formed in front of them.

At the end of November 1939, any inventory of goods in wholesalers' stores was gone, and their keys and all their goods were confiscated without any compensation, although retailers were left alone. This harmed lumber and iron merchants most of all. After a while, flour mills and bakeries were confiscated. Step by step, systematically and consistently, all commerce and industry were taken from the city's Jews.

At the end of 1939, residents were ordered to vote for or against annexing the city to the Ukrainian-Soviet republic. Obviously, the Jews voted for annexation. For fear of the authorities, or because they had no choice – as when the choice was Hitler or the Soviets – they chose the Soviets.

In the spring of 1940 an order arrived for all refugees to register and declare their choice to stay in Russia or return to Nazi-held Poland. Many felt that living under Soviet authority was too difficult and, believing that they would be given permission to leave, declared their wish to return. The result was not what they expected. One night, a squadron of the NKVD took them and their families and sent them to work camps in the Urals and Siberia. (The Polish citizens who had been settled in the vicinity of the city area during the 1930s to give it a Polish character were taken away in the same manner.)

The Jews felt very miserable, but later realized that they had been saved while the others perished.

****

National Jewish life came to an end without the need for the authorities to act. The Jews understood that public activities were not acceptable under Soviet rule and that they had better concern themselves only with their personal needs. The most outstanding public personality in our city was Dr. Binyamin Landsberg, leader of the Zionist movement. He resigned all his public positions, moved to Lvov (where he was not known as a Zionist), and got a job as a teacher of Russian. Then many other Zionist activists and members of the bourgeoisie moved to Lvov and other towns, which saved them from being deported (many people in the town of Dubna were deported). Fear had done its job.

All Zionist and other types of organizations ceased to exist. Everyone devoted himself to adapting to the new way of life. The head of the NKVD in Kremenets was Kovalenko. While he hesitated when Ukrainians and Poles questioned why he did not destroy the Zionist movement's resources, he replied that even if he simply wanted to ban Zionists' activities, he would have to imprison the majority of the Jews of Kremenets in the jailhouse, yet the Zionist Hebrews are useful and faithful subjects to the Soviet regime. And, indeed, the Jews adapted themselves quickly to life under the new regime.

Use of language in public life soon changed. Without being forced, the Yiddish that was used during trade union meetings gave way to Russian and Ukrainian.

[Page 68]

The public and cultural life of the Jews was completely cut off. Ended were meetings and conventions; organizations were terminated; even the Dramakrayz, the trade union organizations' amateur theater group, ceased to exist. The movie house continued to function, of course, but showed only Russian movies.

Key positions generally were given to party members who came from eastern Russia and were “Easterners” (“Vastatshniki”), and they were assisted by some local Communists. For example, Meir Pinchuk (a former member of the Youth Guard turned Communist) was appointed to be in charge of the Lyceum, and his wife, in charge of other schools. The Tarbut School existed, but in a physical way only; it used the same building, furniture, and teachers, but the languages used were Russian and Ukrainian, and the teaching system and content were completely changed.

[Translation Editor's Note: The Youth Guard (in Hebrew, Hashomer Hatsair) was a socialist-Zionist youth movement.]

It is interesting to note that some Jewish laborers who were leaning toward communism thought that now they would be relieved from labor and given positions in government institutions, but the new authorities preferred to choose from the intelligentsia, and rejected them completely, or gave them a minor job, like being in charge of a storage plant. Because of their lack of knowledge in business management, they often got in trouble in their new jobs and later were accused by inspectors of wasting public property; then they were arrested or exiled. True, in the long run [these] actions benefited the exiled, as it saved their lives. Note, also, that the Communist Party was a “closed shop”; for 21 months not one new member was accepted: “Slowly, first you have to adjust to us, prove your allegiance, then your time will come to join” … But the time never arrived.

****

Taking us by surprise, the war between the USSR and Germany erupted on June 22, 1941; four days later, the Germans were close to the city. The residents were inclined to move east, deep into Russia, but an order soon came that no one was to leave his job or he would be considered a deserter. Most people accepted the edict and stayed in town. Only a minority, a few hundred young people, took a chance and left town for the east on June 26–27, while the sound of shots echoed behind them. At the former border, near Yampoli, Lichovtsi, and other places, they got into arguments with the border guard, but eventually were let through to the depths of Russia and thus were saved. Why did many not leave but, instead, stay to be annihilated? There were several reasons for this. First, there was a strong belief that the Germans would win and overtake the escapees, so it was preferable to await them at home and not break up the family. Second, although the Nazi's cruelties were known by then, the atrocities of the extermination were not yet known. Third, many hesitated to endanger themselves by acting against the authorities, who had forbidden them to leave town.

After a while, Stalin's famous order commanding loyal residents to leave their locations, burn and destroy everything, and leave behind only scorched land changed the policy. Many Jewish settlements, such as towns in Bessarabia and others, obeyed the order, moved east, and were saved. For the Jews of Kremenets, the order arrived too late; by the time it was announced, their fate was set for annihilation.

[Page 69]

Courageous Spirit

Brigadier General Y. Avidar (Jerusalem)

English Translation by David Dubin

The bravery and courage of my town's Jews are engraved deep in my memory. They proudly stood up against all foes and attackers, defending their life and honor. From the oldest to the youngest, they were imbued with heroic spirit, and when the time came, they were ready to fight back. Here are some episodes from my youth.

When news about the pogroms in Proskurov reached our town, the School of Commerce, which was attended by Jews and gentiles, was engulfed in an atmosphere of hostility toward the Jews. Provocative writing appeared on the walls, proclaiming “We'll do to you as in Proskurov” and similar sentiments. The Jewish students, a minority in the class, were attacked by hoodlums. A fight in the third grade (13-year-olds) between the two nationalities lasted about an hour, and the non-Jews were beaten badly. The teachers could not stop the fight until the trusted and well-liked school principal, Yefim Konstantinovits Domanski, intervened. He was finally able to stop the fight.

When I was just a small boy in preschool, a Russian student, the son of the police commissioner, insulted me and called me “Zhid.” I did not let him get away with this; I followed him home, hitting him all the way from school to his home. The commissioner complained, and the principal called me and informed me, officially, that a complaint had been filed against me. I replied that it was true, I did hit the boy, but that he deserved it as he had insulted my people. The principal accepted my explanation and did not punish me. More than once, during games, a fight would ensue when a group of Jewish children felt insulted by their gentile friends. And though fewer, they did not shrink back, and they won more often than not.

Brigadier General Moshe Carmel told me his impressions after visiting our town and meeting its young people. In the different towns that he visited as a representative of Young Pioneer, he witnessed incidents of cowardice by Jewish young people when intimidated by hoodlums. In Kremenets, the situation was completely different. When a group of boys were walking out of town near the Ikva River or in the mountains, gentile boys often attacked them. After seeing the reaction of the boys from other towns, they expected this group to run away and were surprised to see them immediately marshal themselves for a “defensive battle,” fighting and hitting their foes until they ran away.

[Translation Editor's Note: Young Pioneer (in Hebrew, Hechaluts Hatsair) was a Zionist organization aimed at preparing young people for immigration to Israel.]

Such were our town's children, such were our young people, and this was the spirit of the adults.

In a later period, during Polish rule, I remember soccer tournaments between Jews and Poles. When the Polish group was going to lose, the Polish audience would start to provoke the Jewish audience, but the gentiles ended up being the losers.

Pogroms were not perpetrated on Jews in Kremenets. This was not a matter of the gentiles of our town and its surroundings, but mainly because the Jewish Kremenets was courageous and knew how to stand and defend itself in times of trouble.

Over the years, in times of civil war and with frequent changes of government, the Jews had established “self-defense” groups of different forms or names. Sometimes they were joined by the gentiles and other times not, according to the situation. However, the initiative and instruction of these groups came from the Jews. In the interval between governments – and sometimes that lasted for days – authority was in the hands of the “Defense.” When the new government was established, the commanders of the Defense presented themselves to the government and handed over the authority and part of the armaments and ammunition.

[Page 70]

Most of the time, the new authorities acknowledged the Defense as a semiofficial civilian force. In this form, it continued until the new “revolution.”

The existence of the Haganah imbued the townspeople with a feeling of security and pride. I can still recall the strong effect on me, a young boy, watching the Haganah's guard platoon striding confidently, guns in hand, in the center of the street, guarding the city's peace. My heart was full of pride, because my brother, Chanokh Rokhel, and my cousin, Avraham Biberman, were two of the guards, erect and confident, their guns bayoneted. I remember well a Polish man, Mr. Visotski, who was a big help to the Haganah organization.

In 1917, all of Russia was raging in the throes of the revolution. On the eve of the Bolsheviks' takeover, hooligans began to erupt. These were not just “underworld” people but also some decent citizens who felt it to be an opportune time for reckoning with the Jews. Near Mr. Goldenberg's store on Sheroka Street, a pogrom was organized under the leadership of an officer in the motorcycle troupe stationed in the area. The Jewish druzhina showed up immediately and dispersed the hooligans. Their evil plot was thwarted.

[Translation Editor's Note: Druzhina is Russian for a select detachment of troops.]

I remember another aborted pogrom in our town. During a change in government, a sort of authority vacuum was created in the city. The gentiles in the suburbs “smelled” the odor of lawlessness; tempted by the army's supplies, which were housed in the large seminary buildings, they started to ransack and loot them. The farmers from the area rushed into town to join them in robbing and looting. A bloody storm was at the city gates. There was no doubt that as soon as the lawless crowd was done there, it would proceed to the Jewish areas of town and start looting and murdering. A pogrom was sensed in the air. Rapidly, the defense groups organized, appeared at the entrance to the center of the town, prevented the gangs of hooligans from entering the city limits, and put an end to the looting.

The self-defense of the Jews of Kremenets was not a passing episode; it existed for many years under different names and forms: druzhina, Home Defense, Self-Defense, and Civil Militia. I remember Mr. Azriel Gorengut, the active Zionist and “government-appointed rabbi” who was a longtime leader of the Civil Militia. The young members of the Haganah trained themselves in the use of weapons. There was a constant concern for the acquisition of weapons and ammunition, as most were acquired from those abandoned during changes of government. Although they were required to relinquish their weapons to the new authorities, they made sure not to be left empty-handed. Most of the time, they owned a few hundred guns. The Defense's ability to organize should be noted. In general, good order prevailed, as well as responsibility, protection of property, chain of command, patrols, passwords, weapons assignment, messenger boys, and even an information bureau to find out ahead of time about impending changes of authority so as to be ready and well organized.

Who were the members of that self-defense? They included mostly Zionist youth and students, but also adults and many ordinary people.

The existence of the self-defense organization in Kremenets was well known in the area, near and far, and maybe that was the reason our town was spared the bloodbaths that visited many towns in Vohlin and Podolia during the years after World War I.

Some attribute the heroic character of our town's Jews the fact that they lived in a mountainous area. But the Zionist idea, which permeated Jewish hearts more and more, strengthened its spirit and awakened feelings of personal and national pride and honor.

****

Courageous youth, a proud Jewish settlement – how you were pillaged!

This material is made available by JewishGen, Inc.

and the Yizkor Book Project for the purpose of

fulfilling our

mission of disseminating information about the Holocaust and

destroyed Jewish communities.

This material may not be copied,

sold or bartered without JewishGen, Inc.'s permission. Rights may be

reserved by the copyright holder.

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Kremenets, Ukraine

Kremenets, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Yizkor Book Director, Lance Ackerfeld

This web page created by Lance Ackerfeld

Copyright © 1999-2024 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 20 Mar 2013 by LA

![kre009.jpg [35 KB]](images/kre009.jpg)