|

|

[Page 15]

[Page 16]

[Page 17 - Hebrew] [Page 363 - Yiddish]

by Binyamin Dubinski

Translation by Martin Jacobs

Geographic, demographic, and statistical data

The town has had many names, although phonetically they all have one source. In Hebrew it was called Divenishok; in Yiddish, Dzivenishok; in Russian, Dyevenishki = Девенишки; in English, Devenishki; in Polish, Dziewieniszki; and in Lithuanian, Deveniskas.

The town is situated on the bank of the Gavya River, which has its sources about 15 km from the town. The entire region is rich in springs of water. The Gavya River flows into the Neman River.

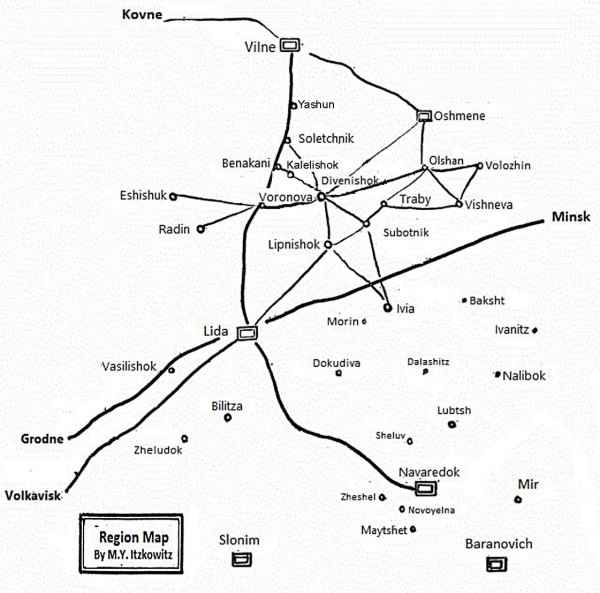

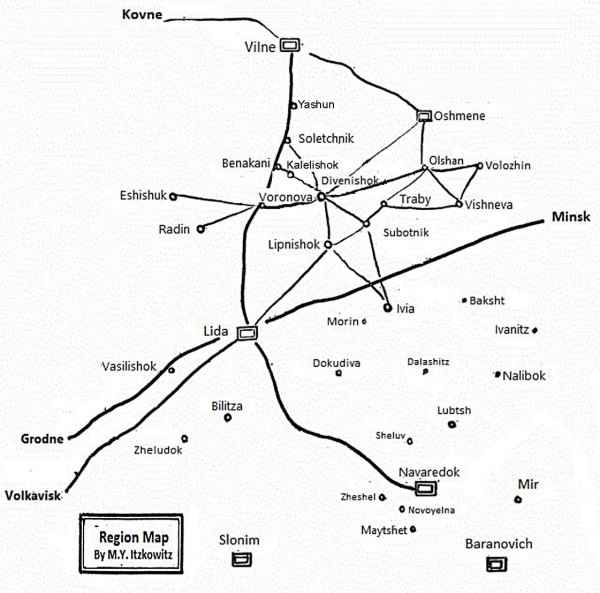

Divenishok is situated on a plateau about 150 meters above sea level, at 54° 12' latitude, 43° 16' E longitude. It is about 30 km southwest of Oszmiana, 63 km from Vilne, 12 km from Subotniki, 21 km from the Benakani railroad station, and about 50 km from Lida.

The origin of the town's name is not sufficiently clear but it is related to the Polish word “dzwon” (bell). On all official documents the bell appears as the official symbol of the town.

The founding of Divenishok; its owners

According to the Slownik Geograficzny [ed. note: geographical dictionary of the former kingdom of Poland and other Slavic lands], in 1433 Divenishok, as well as other properties in Lithuania, passed into the possession of the well known Gasztold [tr. note: Goštautas] family, by order of the Lithuanian Grand Duke Sigmund Kiejstutowicz. In 1500 a Catholic church was established in the town by one of this family. After the last of the Gasztolds, Stanislaw, died, the town passed to the guardianship of King Sigmund; that was in 1542. And so it was transformed into a state possession, administered by a starost [tr. note: governor of a province in Poland].

In 1782 Marshal Jadka ruled Divenishok. (“Marshal” was a designation for Polish nobility; he was a descendant of a convert to Christianity, who was given a noble title.) Rental on his estate brought him a yearly income of 1,184 zlotys.

In the 19th century there was a distribution of town lands, as a result of which agricultural parcels were divided among the Christian residents (who were called “mieszczanin” [tr. note: burghers, townspeople]), except for the hundred desyatin [tr. note: obsolete Russian land unit, one desyatin is equal to 2.7 acres] of land granted to Nazaretski, a state official.

In 1880, 843 Christians lived in the town; their principal occupation was agriculture. Jews formed the majority of the town's population, and they were in trade and handicrafts. They made a good living, especially at the weekly market days and at the two great yearly fairs.

The community included nine rural areas with 90 villages and 5,796 residents. It is surprising that the Geographic Dictionary gives no information on the number of Jews in Divenishok, since it does have information about the number of Jews in other towns.

The founding of Jewish towns in Lite

The beginnings of the Jewish settlement in Divenishok are shrouded in darkness, as is the blossoming of all the small towns on the broad plain between the Neman, Gavya, and Vilija Rivers. For the most part this area is covered with virgin forest, green meadows, and flowing streams, extending over a terrain of thousands of kilometers.

There are creditable documents attesting to the presence of Jews in Lithuania as early as the ninth century. Bishop Adalbert of Prague, sent in 997 to preach the Gospel to the pagans in Lithuania, relates that “many Christian prisoners are sold to Jews for money and he was not able to ransom them”. It is also known that there was a large Jewish emigration from western Europe to Lithuania in the 14th century, during the rule of Gediminas (1316-1341), who expanded the borders of the Lithuanian state to the Neman and the Bug. Gediminas was a pagan, free of anti-Jewish complexes, and he opened the gates of his land to the persecuted Jews of western Europe. His grandson, Witold Vytautas (1392-1430), Grand Duke of Lithuania, also had a sympathetic relationship with the Jews. He even published a “Jewish Law” of 37 paragraphs which granted special rights to the Jews. Witold's laws for the Jews of Lithuania essentially resembled the charters of Duke Boleslaw of Kalisz for the Jews of Poland and recognized their civil, religious, and commercial rights, and granted permission to move freely across the entire land. The Lithuanian population, pagan until the second half of the 14th century, knew nothing of anti-Semitism and had honorable and tolerant relations with Jews.

The beginning of the Jewish settlement in Vilne and environs

Vilne was founded in 1323 by Gediminas, Grand Duke of Lithuania. From that time on Jews little by little began to settle in the city and basically engaged in trade and brokerage. The Jewish population of Vilne grew very slowly. In 1520, when the Council of Four Lands was formed, only three communities of Lithuanian Jews were represented in it: Brisk, Horodne, and Pinsk. The size of the Jewish population of Vilne at the time did not justify representation in the Council. Only after 1623 were the communities of Vilne and Slutsk included in the Council of Lithuanian Jews. This means that only more than 300 years after the founding of Vilne had its population increased significantly enough to justify its joining the Council of Lithuanian Jews.

The development of the Jewish settlement in the Vilne area paralleled that of the city itself. Individual Jews settled in each administrative center and wherever a Catholic church had been built. There they had the prospects of a decent living. Jews settled in the villages near the center and so began the spread of Jewish settlement in the region and in Vilne.

A decisive factor in the growth of the Jewish population in the Vilne region were the massacres of 1648 and 1649. At that time Bogdan Khmelnytsky lead the Cossacks in a holy war against the Polish land owners. In their bloody path the Cossacks destroyed entire Jewish communities in the Ukraine and Podolia. A stream of Jewish refugees began to flow west, many of them coming to our region. Survivors of these pogroms also settled in Divenishok.

The Russian-Swedish war

The Jews in the area lived through hard times during the war between Russia and Sweden at the end of the 17th century. The Russian army swept across Poland and Lithuania and in 1655 it occupied Vilne and its environs. There were pogroms against Jews in Vilne and Grodne, but there are no historical reports of pogroms also taking place in the surrounding small towns such as Divenishok.

Carl Gustav X, King of Sweden, who was then at the height of his military power, exploited the anarchy in Poland to launch a surprise attack on Russia. His armies took all of Lithuania by storm and reached Vilne and even areas to the south. To the present day there are testimonies to the Swedish presence in our town. About five kilometers from Divenishok, on the highway from Vilne that goes through the Dubink forest, lies swampy terrain which makes passage difficult, especially on rainy days. The Swedes solved the problem as they did in Sweden in those days. They sawed pine from the forest into planks and covered the roadway with layer upon layer, and in this way created a bridge over the swamp and solved the problem of crossing the mud. The remains of that bridge are still visible and the locals call it “shvedska greblia” (ed. note: the Swedish embankment).

The period of the Russian occupation

Three times, in 1772, 1789, and 1795, Russia, Prussia, and Austria partitioned the Polish state among themselves. After the third partition the largest part of Poland came under Russian rule and the Jews of Lithuania found themselves subject to Catherine the Great, the “enlightened” empress, who immediately defined a Pale of Settlement for Jews and issued harsh decrees against them, such as an absolute prohibition of living in villages. The Jews who in the course of generations had put down roots in the villages, and had their own land, were forced to leave everything and move into the towns empty handed.

In 1804 the expulsion began. It was interrupted by Napoleon's invasion of Russia. The expulsions were renewed after Napoleon's defeat and continued intermittently throughout the 19th century. These expulsions led to a flow of population into the cities and towns; this is one of the reasons for the increase in the Jewish population of Divenishok.

The Russian occupation also had positive aspects: Large markets in Russia opened up for the Jews of Lithuania. This led to economic prosperity in the Lithuanian towns. The religious and cultural connections between the Jews of Lithuania and Russia were also broadened, as is shown by the distribution of newspapers and the publication of religious books and research books.

The age of upheaval and change

The years from 1914 to 1945 were full of difficulties and afflictions, because power passed from hand to hand. In 1915 the Germans occupied the town and were in control for two years. After that the Bolsheviks were in control; they stayed briefly, until the Poles expelled them. In 1919 the Poles set up their administration in the town, which lasted until 1939, when Divenishok was taken by the Soviets. In 1941 the Germans again took the town. In 1943 the Germans transferred it to the Lithuanians. When the region was taken by the Soviets in 1945, the town was finally transferred to the Lithuanian Soviet Republic, to which it still belongs [ed. note: Divenishok is currently in the Republic of Lithuania].

Development of the Jewish community in Divenishok

As a result of the break in communications with Poland we have no documents which can shed light on the beginning of the Jewish settlement in Divenishok. The only authoritative source we possess is the Yevreiskaya Entsiklopedia [tr. note: Jewish Encyclopedia] by Katzenelson and Ginzburg, according to which there were 94 Jews [ed. note: could mean 94 families] in Divenishok in 1766. In 1847 the town had 240 Jews [ed. note: could mean 94 families] and in 1897 [ed. note: 1897 is probably an error since the Jewish encyclopedia reports this date as 1898] there were 1,897 residents in the town, 1,225 of them Jews.

It should not be inferred from this that there was no Jewish settlement in Divenishok many years earlier. The fact that in 1500 a Catholic church was established there and the place was designated a regional center raises the possibility that individual Jews were already living there in the sixteenth century, since they could live and develop peacefully there. It also seems reasonable that individual Jews, engaging in brokerage and agriculture, lived in the surrounding villages.

There is reason to believe that in 1652, with the inclusion of Vilne as an independent area in the Committee of Lithuanian Jewry, the population in Vilne increased at the same rate as the population in the area as a whole, including our town, although this cannot be proven from the historical data, since the head-tax which the Jews of the small towns paid was included in the total accounts of Vilne and the region.

Some data can, to a certain extent, throw light on the beginning of a Jewish settlement in our town. As is the general custom, cemeteries are at somewhat of a distance from settlements. In Divenishok the cemetery was located in Magazin, more than a kilometer from the town. However, at the same time, an old cemetery was located in the town center, about ten meters from the market. It had not been used for more than a hundred years. The grave stones were half sunk into the ground and overgrown with vegetation, showing beyond all doubt that the town was first built far from its present location and for unknown reasons was moved to where the town cemetery was located. Even the most elderly townspeople did not know where the town had first been. They could only say that the cemetery had graves from the year 5450 [tr. note: 1690], that is, about 300 years ago.

I remember that there was a special synagogue for praying in summer in Divenishok. In its women's section there was an inscription carved into the wood: “This synagogue was built in the year 5500 [tr. note: 1740]”, 235 years earlier. That it was able to build a special summer synagogue for itself shows the economic strength and spiritual vigor of the Jewish settlement in the town.

The synagogue collapsed in the twenties and was replaced by a Hebrew school. In order not to destroy the holiness of the spot the rabbi decreed that an ark with a Torah scroll be placed in one of the classrooms, and there people prayed from time to time.

I remember that in the study house there were several bookcases with ancient volumes of the Talmud, which had been printed in Livorno, Italy. There were yellow drops of candle wax on them, proving that hundreds of years before, many scholars had lived in the town and spent their days in the study of the Talmud and Mishna.

From everything mentioned above it follows that a Jewish settlement in Divenishok was forming in the 16th century. At first it was very small in scope, only a few dozen families in the town and the surroundings. Because of the persecutions of Jews both in the east and the west the settlement continually grew and developed into a typical town. It is difficult to determine if the dominant majority in the town consisted of Jews who came from the east, from Russia, or German Jews who came from the west. In the opinion of Rabbi Joseph Movshovitsh the great stream of Jews came from Germany. He cited as proof the great number of family names which sound German, like Levine, Kuhn, Becker, Pludermacher [tr. note: could also be Fludermacher, impossible to determine from original text], and others. The Rabbi had also heard that the grandfather of Justice Frankfurter of the United States Supreme Court had once lived in Divenishok and had owned the Pushpeshk farm. But many Jews changed their names, so as not to serve in the Czar's army, thus hiding their true identity. In addition Jews in Germany had close commercial ties with Jews in the Baltic lands; in time of trouble they of course found a refuge in tranquil Lithuanian towns.

In the seventeenth century the town was in its beginnings and only towards the eighteenth century did it begin to crystallize into an ordinary Jewish settlement. In that century the development of the town was dynamic and economically strong. In the nineteenth century the town grew in size and in quality because of the expulsion of the Jews from the villages. After that, however, the town lost population as a result of the mass migration to America, which continued into the twentieth century.

For over 400 years the quiet charming town existed in the thick forests of Lithuania, until the German enemy came and wiped it from the face of the earth. May the curse of generations cling to him forever.

Municipal affiliation

During the Polish-Lithuanian Union Divenishok belonged administratively to the region of Lida and was under the jurisdiction of the regional court in Lipnishok. It received its mail by way of Subotniki, a town 12 km away. After the last partitioning of Poland (1795) the Russian authorities did everything they could to Russify the region. An Orthodox church was set up at the market place in Oszmiana and a Russian school was opened in the city. Oszmiana was designated a regional seat, taking in five towns, including Divenishok. According to the 1880 census a total of 11,131 Jews lived in the entire Oszmiana region.

Starting with the Russian occupation Divenishok belonged to the Vilne gubernia (region) and the Oszmiana oyezd (district). When the Vilne-Baranovich railway line was opened mail began to come to Divenishok from the Benakani railway station, 21 km away.

In the period of Polish rule (1919-1939) Divenishok belonged administratively to the Vilne voyevod (region) and Oszmiana powiat (district). During Soviet rule it belonged to the Oszmiana Rayispolkom (Regional Executive Committee) and the Grodne Oblast (region), within the framework of the Belorussian Soviet Socialist Republic, with its capital in Minsk. Since the Soviet occupation Divenishok has belonged to Lithuania and administratively to its capital Vilne.

Employment and economy

The economy of the town was principally based on commerce and crafts. Agriculture supplemented the income of land owners. The Slovnik Geograficzny [ed. note: geographical dictionary of the former kingdom of Poland and other Slavic lands] indicates that the town included nine rural regions, which included 90 villages. Trade was in the hands of the Jews, who made up a dominant majority of the town's population. Commerce brought the Jews a good living during the regular market days and the two great semi-annual fairs. The situation did not change in the 20th century. Trade with the surrounding villages served as an essential basis for Jewish existence in the town. Such a situation characterized all towns in Lithuania from their founding.

The market days were days of strenuous administrative and physical activity which determined the extent of Jewish earnings for the week. Bearded burghers would stand at the thresholds of their shops looking for customers. Merchants, coachmen, and traders urgently hurried to buy produce from the farmers before the competition could get there. Peddlers and salesmen invited customers by calling and gesturing. People bought and sold everything they had. The other days of the week the town was quiet and life was lazy. Everyone was getting ready for the next market day.

Before the 20th century we have no data on the occupational make up of the population. The Jewish Encyclopedia has information on this matter basically for the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the twentieth. The 1898 census reports a population of 1,877, of whom 1,283 were Jews. There were 277 craftsmen in the town; about 66 women made their living from knitting socks which were sold in Vilne. Approximately ninety three people were day laborers and the rest of the population was in commerce. Charitable organizations in the town included the shelter for poor travelers, a free loan fund, and the society for visiting the sick. In addition there was a library with Yiddish books, a school with 84 students, a Jewish religious school with 20 pupils, and five Jewish elementary schools with 56 children.

It should be noted that knitting socks was an exceptional occurrence in the town and only a temporary one. Only three towns were engaged in this occupation: Molodetchno, Kobilnik, and Divenishok, and only until the large knitting mills were set up in Vilne and other cities.

Life in the town followed the same fixed patterns as in all the Lithuanian towns. For hundreds of years life flowed by “beside the still waters”, unchanged and undisturbed.

Employment and one's economic situation determined the status of everyone in society. Wealthy people and established shopkeepers were considered the most respectable. Most of the town's residents hunted for work and lived by the toil of their hands. Despite difficulties in making a living the Jews were proud, with a strong Jewish and national consciousness. Many of them emigrated, looking for a better life.

The fires

Our town experienced two large fires and several smaller ones. In 1912 a big fire broke out in the marketplace and almost destroyed the whole town. There was a second fire in 1932, in which many houses in the market burned. The fires impoverished the townspeople, but thanks to mutual help those who suffered from the fires were able to rebuild. We should emphasize that helping each other in the event of a fire was taken for granted in Lithuanian towns. So we find in the newspaper “HaMelits” in the year 5652 (1891) that Divenishok is listed among the towns which gave valuable assistance to the Jews in Lida after the great fire in that city.

In the First World War

With the outbreak of the First World War the situation in the town worsened, especially after the Germans came in 1915. They seized the young people in the town for forced labor (in the so-called “Fonye battalion”) and stole food from the villages. The situation worsened daily. On top of this typhus was spreading through the surrounding area and many fell victim.

In the registry book for Y.K.P. [tr. note: Yevreski Komitet Pomoshchy (Jewish Aid Committee)] for that period we find a report from Divenishok: M. and S., 10 and 13 years of age. Father died of typhus. Mother blind. S., her 13 year old daughter, runs the household. The house is not fit to be lived in and might collapse. By pleading, the girl can get a little firewood from good hearted neighbors to warm the family. There is suffering, distress, and poverty in the town.

The Y.K.P., a well known philanthropic organization, undertook the task of helping the town. Urgent meetings in Vilne were arranged; delegates from Divenishok, Arye Leyb Rogol and Rabbi Movshovitsh, participated. Urgent assistance was sent to the towns of the area, including Divenshok. A public kitchen was opened for the poor; the needy received help with food and clothing. This situation continued with the arrival of the Bolsheviks in the town and improved when the Poles came.

Polish rule

Polish rule can be divided into two periods. The first was the time of Marshal Pilsudski. He treated the Jews with tolerance; their economic situation achieved a certain stability. In the second period, which succeeded Pilsudski, the position of the Jews worsened more and more as a result of an increasing wave of anti-Semitism. The Poles began to remove business from Jewish hands; they opened shops and cooperatives in every town and village; they organized a boycott of the Jews with the slogan “swój do swego” (everyone for his own people).

We read in the report of the Y.K.P. about the position of the Jews in Divenishok at that time: There are 250 families in Divenishok, 140 of them Jewish. Principal occupations: shop keeping, trade with the villages, crafts, sewing workshops, and clothing manufacture. There were 60 shops in the town owned by Jews and two Polish cooperatives which received financial aid from the local government.

Merchandise in the cooperatives was brought from the central warehouse in Benakani. The Jewish merchants brought their merchandise by wagon from Vilne. Because of the expense of the transportation, the excessive number of shops, and the fierce competition from the Polish cooperatives, the Jewish shops were in a very difficult position. The weekly market day was held every Thursday. About 20 to 30 families made their living dealing in produce from the villages (korobelnikes [tr. note: peddlers]). There were five sewing workshops for clothing manufacture in the town, employing 40 men and women, who earned 20 - 30 zlotys a week. Their products were marketed in the neighboring towns of Vishneva, Trok, Olszanica, Oszmiana, etc.

Two expert Polish shoemakers and one carpenter also worked in the town, but no builders. Five Jewish families had five desyatin each of agricultural land. They tilled the land themselves or with the help of day laborers. There were also Jews “who lived from the air” (“luftmentshn”): brokers, match makers, peddlers, etc.

From 1939 to 1941 the town was under Soviet rule. It took just a few days for the Red Army to make off with everything in the shops. Business stopped completely and most of the Jews lived from hand to mouth. They engaged in illegal trade and in selling what was left from Polish times. Life became gloomy and oppressive.

In July of 1941 the Germans entered Divenishok and our community was cruelly destroyed.

Bibliography:

- Dr. Raphael Mahler, Toledoth haYehudim bePolin, “Siphrith haPoalim”, 1946.

- Prof. Sh. Dubnov, Pinkas haMedina shel Vaad haKehiloth haRishioth beMedina Lita, Berlin, 5688 [1928].

- Prof. Sh. Dubnov, Dibhré yemé olam, Debhir publishers, Tel-Aviv 5710 [1950].

- Moshe Shalit, Af di khurves fun milkhomes un mehumes, Pinkas fun gegnt komitet Y.K.P., Vilne 5691 [1931].

- Sepher Yahaduth Lita, Tel-Aviv 5727 [1967].

- Sepher Oszmiana, Tel-Aviv.

- Sepher Lida, Tel-Aviv.

- [ed. note: skipped]

- “HaMelits”, 5662 [1902].

- Tsaytshrift far geshikhte, demografye un ekonomik, Minsk 1928.

- Slownik geograficzny, Bronislaw and Filip Chlebowski, Warsaw 1882.

- Yevreiskaya entsiklopedya [Jewish encyclopedia], Dr. Katzenelson and Baron Ginzburg, Peterburg 1912.

- Yevreiskaya entsiklopedya [Jewish encyclopedia], Brockhaus and Efron, Peterburg 1912 [tr. note: may refer to “Entsiklopeditcheskiy slovar” [Encyclopedic dictionary] published by Brockhaus and Efron in St. Petersburg (1890-1907)]

- Jewish encyclopedia, New York and London, 1903-1916.

Eliohu Wiener

Translation by Meir Bulman

When the Bolsheviks occupied Poland in 1920, a harsh famine took hold of Divenishok. The situation had not improved much even after the Bolsheviks retreated and the Polish regained control. Skyve's home we knew had burned down, and so we had to move to Chaim Gershovitsh's house, which was previously used as a school.

Wandering, Starving, Dying

I remember an episode from those days. Nathan Kaplan's grandfather had a large plot of land behind his house, where he grew potatoes. Since the famine was so severe, the cobbler's son, Hershl Pinchas Katz, and I snuck into the garden, took out the planted potatoes, cooked and ate them, skin and all.

After a while, the hunger at home became unbearable. My mother Sarah, my brother Leybkeh, Yitzchak Schneider (whose brother was Leyzer “Der Voyevada” [Ed. Note: as a verb voyeven means to howl or to roar, or, to romp or frolic, which could be a character description, or a voyevode is a Provincial Governor, which in this case could be a tongue–in–cheek epithet], and I decided to head to Grodne. We had heard by way of a rumor that the situation there was better. My sick father stayed at home and my sister Tzirah Leah stayed to care for him.

We wandered from town to town and asked for food. We were not ashamed at all, since it was a time of mass–wandering. When we got to Grodne, we contracted Typhus and were hospitalized in town. I was the weakest among us and spent a year in the hospital.

On our way back, we traveled through Shtutchin, a city near Lida. My brother, who was 16, landed a job as a tanner. Thanks to him we had the chance to lodge in the corner of the room where skins were dried. The stench of the skins was overwhelming, but we saw a positive aspect in having a place to rest our heads. Shortly we were informed that our father Yoel had passed away, and my sister Tzirah Leah moved to Vilne, so we decided to not return to Divenishok and to stay put in Shtutchin. In 1934 death came for my mother too. My brother married and worked as a cobbler, but his hobby was writing poems. He was an intelligent young man and locals came to him to write addresses in America for them.

In 1931 I traveled to Vilne to attend a trade school, “Hilf Dorkh Arbet” (Assistance Through Labor), where subjects like carpentry, tailoring, drawing, and more were taught. I chose drawing. I was accepted to the school as an orphan and received three zloty a month as spending money, as well as vouchers for the soup kitchen on Vilner Street. Because the availability of sustenance worsened at school, I decided to work as a tailor's apprentice and learned that trade.

Escape to Russia

In the early 30's the situation in Poland was at a low point. Mass unemployment and heavy taxation burdened the Jewish population. As a result, a movement began of Jewish youth emigration to Russia, and I too decided to cross the border.

My friend Zelda, another friend, and I, connected with a farmer who lived on the border. Upon his recommendation, we arrived at a hotel in Ivanitz and transferred from there to the farmer's house. We hid three days with him until the weather became rainy and dusty, and on a dark and misty night, the farmer took us beyond the river and instructed us to walk towards a field whose trees looked pale through the mist.

We crossed the border and Russian guards led us to Koydenovah Camp, where there were about 200 people, mostly Jews, as well as some Poles and Lithuanians.

After a staying a few days in the camp, we realized that we had been foolish and had gotten ourselves into a venture for which we might pay with our lives. The sanitary conditions were atrocious, and all the prisoners were hungry, exhausted, and crawling with lice. The Russian prisoners were wearing rags, and we learned from them about the terrible situation in the Soviet Union. Many young men were on the brink of despair. It seemed that what the Poles had been unable to carry out in the way of torture and detention camps, the Russians had accomplished in a mere few days. The dreams of a Russian utopia vanished, and everyone had but one dream: the return to capitalist Poland.

I was lucky, as I began to work in the kitchen and at least could have access to larger food portions. A meager 200–gram slice of bread, and soup containing horse's head and carcass were our nourishment, and even that was scarce.

Along with that, the Russian were experts at interrogation. For six weeks various officials interrogated us daily. Once I was even interrogated by a Jewish man from Radin, who had probably already arrived in Russia by WWI. Interrogations were meticulous and thorough, and every detail was written. In all interrogation sessions we were offered a return to Poland for a spying mission.

During my interrogations I claimed repeatedly that I had escaped from Poland due to a lack of employment and the rumor was that in Russia all youths are given the opportunity to learn and progress. I feared a trap and maintained my position stubbornly, and the interrogators failed to break me.

The early interrogation sessions were conducted gently, but as time went by they acquired an increasingly confrontational tone and were accompanied by swears, threats, and insults. Our spirit was suppressed because we had not expected this “warm welcome” for youth such as ourselves, full of ideals of justice and brotherhood. The cat was out of the bag and we were now acquainted with this “progressive” regime.

The Release

After six weeks my friend and I were summoned from the holding cell to one of the interrogators, our clothes were returned and we were told we were being sent back to Poland. Later we were joined by our friend Zelda who came to Russia with us. At night we were led to a location near the border by a Russian woman wearing a military uniform. The woman gestured where we should head to cross the Polish border.

We were fearful since we had heard of young men who had snuck into Russia, and then when crossing back were thought by Polish officials to be spies and were brutally tortured. One man from Mir was tortured to death in Baranovich, and as a cover–up the prison guards hung him, claiming he committed suicide by hanging.

While being aware of all this we changed course with the clear intention of being captured by Polish border control. We knew that we would remain imprisoned for a while and then would be released. And indeed, border patrol captured and imprisoned us. My interrogation sessions were uneventful, but other prisoners notified me that my friend was being harshly tortured because of the few dollars that were found on his person. I understood what the issue was and decided to rescue him (he was suspected of surveillance), and asked for an interview with the chief interrogator.

At the meeting with the chief I said that we had come to the town of Ivanitz even before crossing the border to Russia, and there we had stayed for a day at a Jewish hotel. We exchanged our Polish money for ten dollars we could use in Russia, and my friend had sewn the bill into his shirt collar. The Russians were unable to find the bill, but the Poles had succeeded, and so this is why he is being accused of spying. “The truth is,” I told the interrogator, “that the guy did so with no ill intent”. To prove my claim, I provided him with the hotel owner's name. The Poles confirmed it and my friend was saved from tragedy.

A few days later we were tried for illegally crossing the border and were sentenced to two months in prison. Compared to the Russian camp it was a luxury hotel.

After our release from Stolpce prison, we wandered without wages or a means to return home. A certain detective who saw us aimlessly wandering a border town like Stolpce suspected we were trying to cross the border to Russia. He arrested us at the train station and promptly sat us on the train to the Vilne police. We had not told him a thing, because we were interested in reaching Vilne, but once there we told the truth and confirmed our claims with documentation. We were released to the detective's shame: he had inadvertently assisted us in reaching our destination.

For many years, the reason for our release by the Russians was a mystery to me, since many of our acquaintances were sent to Siberia where their souls departed them. But only thirty years later in Israel the mystery was solved. I happened to meet a childhood friend from Zheludok, which is not far from Shtutchin. I knew that he too had been in Russia and we got to discussing the old days. He told me he had escaped death by “activating” a spy. The interrogator in Russia had given him half a kerchief of some girl named Zelda and had told him to show it her and inform her of her mission. That is how it became apparent why we had been released. Zelda could not withstand the pressure and had accepted a surveillance mission. To not raise any suspicion, my friends and I were let go too since we had crossed the border with her. Of course, Zelda later suffered for her recklessness. After my return home, I presented myself for military duty, but was declined for political reasons. Due to the lesson I had learned in Russia, I abandoned my political work and began training as a tailor.

As WWII erupted in 1939, I visited my relatives by Leybeh Eydel's daughter Bilha in Divenishok. After the collapse of the Polish regime, it was difficult to return to Vilne, since it was unknown who would control it. With many difficulties, I made it to a restless Vilne. The Poles had vanished and the town was without a government. The Jews feared that the gentiles would launch massacres against them. To maintain order until some sort of government could form, the Culture Department of Professional Unions organized the Workers' Civilian Guard, “Rabochaya Gvardia,” to operate governmental functions until commands were clarified. I was among the active members of this organization. The leaders were two Jewish men, Kroshkin and Shuchman, and they took hold of police warehouses, distributing weapons among members who went to patrol the town's sensitive regions. That arrangement continued until the Lithuanians entered, when the civilian guard disbanded, with some members joining the Russians and others remaining in Vilne.

I left Vilne on my way to Lida, where I married my wife Sarah. Together we returned to Vilne where I worked as a tailor until the war commenced. In the days of German control I was in various detention camps. After being liberated, I arrived with my wife in Israel, and here my two daughters were born.

Orit Kaplan

Translation by Meir Bulman

In 1923, in a town named Divenishok , which was located 63 kilometers south of Vilne, on Rosh Hashanah, the youngest child was born to an established Jewish family. That child would later become my father. He had four sisters and one brother– and of course his older sisters pampered him. His father– my grandfather– was the town's bank manager, a landowner who employed Christians from the nearby villages as land workers. He also owned a food supply store and was the synagogue administrator.

There were 5000 Jewish residents in the town, aside from a number of Poles who worked in local government and the police force. There were a few Christian families that made their living providing janitorial services to Jews.

Once a week a market day took place in the town. The nearby farmers brought their produce to sell and would buy their necessary products. The entire town profited from the business generated by market day. The noise level was high' auctioneers and jugglers performed too. All of that made market day a great economic and social event.

The town had a large synagogue and nearby was a Hebrew School with 7 classrooms. On Fridays, the Sabbath, and on holidays, town Jews gathered there for prayers. My grandfather had a designated honorary spot by the ark, which had been inherited for generations, and my father was obliged to join him there. As a young boy the reciting of the prayers was a burden to him, and he would sneak out with the other children to play in the synagogue yard. Before prayers concluded he would sneak back into the synagogue. His father would usually scold him for his mischief. The synagogue was a meeting spot for many Jews, who came to pray three times daily. Jews who did not have time to attend services prayed at home.

After my father completed sixth grade at the Hebrew school he transferred to the local Polish public school named for Adam Mickiewicz, a well–known Polish poet. The school was attended by Jewish children who had completed Hebrew school, as well as the Christian farmers' children. The percentage of Jewish students in that school was small. There were usually 5 to 8 Jewish students and between 30 and 40 Christians. The Jewish children excelled at their studies, especially in mathematics. There was a tense atmosphere at school and there were few social interactions between the Jewish and Christian students. There were occasional squabbles between Jews and Christians. Once a quarrel erupted between my father and one of the Poles, whose parent was employed by the town. Although neither child had complained, the matter was brought to the principal's attention. As punishment they were forced to carry rocks on a stretcher from the school yard to the field. After they worked cooperatively for two hours they were released by the principal, and since then, despite incitements by other Christians, they remained good friends until my father emigrated to Israel.

Even as a child my father excelled at athletic activities and thus the principal appointed him director of team sports. In one of the volleyball competitions he added five Jews to the school team, as well as his Christian friend. The school principal objected to that, adding two more Poles. Only after he realized that his line–up is causing the team to lose did he agree to my father's line–up, who then led the team to victory.

On Polish Independence Day, annual prize–granting sports competitions took place, in which Jews did not participate. At the age of twelve, a year before my father emigrated to Israel, he decided to participate in the boys' 60–meter sprint. He had to run numerous times before the finals and the organizers realized that his competitors did not stand a chance;, they added two young men, but their plan failed, and my father was the first past the finish post. Additionally, he won first place in the long jump. An important noteworthy fact is that the Christian mayor, who was an anti–Semite, had to announce the victory of a Jewish boy, and his face flushed with rage, he shook my father's hand in the presence of the Polish aristocracy. My father still recalls that they murmured in wonderment: “How is it that no Pole succeeded in catching up to the Jew?”

As news of the event spread through town, my grandfather, who was a fundamentalist, Orthodox Jew, came to the field looking for my father, who was afraid his father would be angry. But my grandfather approached him, and though his eyes were radiant, he did not say anything, took his hand affectionately, and with a heart filled with satisfaction said: “Nu? Come home”.

A year later my father emigrated to Israel with his parents.

In Israel he attended “Ahad Ha'am” high school in Petah Tikva, and lived with his parents at Kfar Ma'as. This period was a bloody chapter in the history of Israel. His parents' house was right on the border. Beyond the fence there was an Arab orchard from which shots were fired at night. Residents guarded positions to prevent Arabs from breaching into the village. Since my grandfather was an elderly man and could not participate in guard duty, my father replaced him on many nights, and as a result had to cope with drowsiness during school hours. He once earned a teacher's scolding who had sensed his lack of alertness in class and his desire to doze.

My father's home was a traditional one where religious commands and customs were strictly adhered to. My grandfather was also an enthusiastic Zionist basking in the glory of the Kingdom of Israel. During his childhood my father inherited from his father a pride in the bravery of the Kings of Israel in the spirit of the Bible, where prophets and kings are described as visionary heroes, glorifying the Kingdom of Israel.

Considering this education, it was natural for my father and grandfather to make Aliyah, and afterwards for my father to fight for Israel's independence, following which he founded a family in Israel.

by Meir Yosef Itskovitsh

Translation by Meir Bulman

I put the term in the title as we all knew it, both Jews and gentiles. It essentially means what we know today as a civil guard.

Every night, four people, each one from a different household, would patrol the streets of town until dawn. The role of the varte was to guard the lives and possessions of the residents of Divenishok. In case of a burglary, the police had to be woken, and in case of fire, the siren had to be sounded and the fire department summoned. The next night, four people from the homes next in line patrolled and so on until the final person at the edge of town was reached and the cycle began again. Usually, a member of the households would patrol, but when it could be afforded, a gentile would be hired for the task.

I remember one night when I returned home for summer vacation from gymnasium. The duty of varte reached our house. I approached father and asked him to hire me instead of a gentile, since I would patrol town into the late hours of the night anyway. To my delight father agreed.

At midnight I was on varte duty joined by my great–uncle, and the daughter of Alexander (Oless) Pezkovski the tailor. As a typical young man, I could not walk calmly and withstand the temptation of blonde–haired Helenka, and on the balcony (ganek) of Nachum Lipkunski the bakery owner, we made a connection. I do not remember what we discussed or did not discuss, but I remember that we were so absorbed in conversation that we did not notice that on the horizon, from Dubtshinski Street, the sky turned red and an entire village burned, without us noticing.

The next day, a ruckus was raised: How could it be? How did the varte not notice the fire? Why was the siren not sounded? Who was on watch?

Imagine what I went through. I shook in fear, but as they say, ‘oysgekrenkt dem gantsen fargenign.’[1] Who knows how the whole ordeal would have ended if not for my father, who was a member of the town council and accepted and respected by the authorities. Thanks to his intervention the sad events of the varte night were put to rest.

Editor's footnote:

Dr. Menachem Weisenfeld

Translation by Martin Jacobs

I was born in Galicia, in the town of Zuravna, located between Lemberik and Stanisle. There I completed elementary and middle school and then went on to study medicine at the University of Vilna. I was one of the students who supported themselves by giving lessons. Among my pupils were the children of Slonimski , the well known attorney, one of the leading Zionists in Vilna.

When I finished my studies at the university I learned that Divenishok needed a “sejmikowy” (regional) government physician. A permit for this was given only by the starosta [Ed. note: district administrator] responsible for the district, who lived in the city of Oshmene. The Poles never have distinguished themselves by their love of Jews and the starosta had never certified a Jewish physician for this position. But I tried my luck and sought an appointment with him. The man gave me a penetrating look and spoke with me briefly. He apparently liked my “non-Jewish” face and my fluent Polish; he directed me to his secretary to have the certification forms filled out. When the secretary read my diploma, in which my given name, Menachem Mendel, was recorded, her eyes went dark, but without a word she filled out the documents and the starosta signed the contract.

At the end of December 1928 I arrived in Divenishok, where I stayed with the pharmacist Arye Leyb Rogol. He was already seriously ill and the pharmacist N_ [Ed. note: accurate name translation not possible as written in text: nun-mem-yud-vov-tes] was working with him at that time. In addition to my work as a physician, I was responsible for the sanitary and hygienic conditions in the town, and it was my job to go out with the chief of police to inspect businesses and courtyards for cleanliness.

Before I came this had been done by the public health doctor of the district seat, Oszmiana, and the Jews had to put up with a lot from him, especially the restaurant owners, bakers, and business owners. Depending on how good his mood was, he wrote summonses right and left – “let the Jews put a bit of money into the state treasury” – he used to say. The appearance of this sejmikowy physician in the town was like a visit from a ghost, because the Jews were terrified of him, since most of them were very poor and it wasn't just once that they had to run around wherever they could to borrow a fortune to pay the fines.

With my appearance in the town a great feeling of trust came upon the Jews there. My wife was very friendly with the family of Noah Kartshmer, and if the townspeople found it difficult to get close to him, my wife, Rosa Ostrinski, found him approachable. She was known in the town as the daughter of Ostrinski, the well known Vilne merchant, and it was due to Noah Kartshmer that she could let the townspeople know when the sanitation commission was about to make an appearance.

The police chief used to say to me: “The townspeople must be afraid of you. Since you've been the physician here hygiene has been exemplary and it hasn't been necessary to write summonses.”

Once a week I visited schools in the villages in the vicinity to investigate sanitary conditions. In this capacity I checked on the health of the Polish teachers to see if they were fit to be teaching. A carriage with two horses and a coachman was at my disposal. The townspeople were overjoyed when I went through the streets of the town in the carriage. I was in close contact with the police officer and the Christian priest, a man of Lithuanian origin named G_ [Ed. note: possibly Gedgaudas; accurate name translation not possible as written in text: gimel-daled-gimel-vov-beyz-daled]. We visited with each other, and took walks together through the streets of the town. The Jews were very pleased that the priest was friendly with the Jewish physician.

At government ceremonies, which were celebrated with great pomp, I appeared on the reviewing platform in the uniform of a Polish officer, in sight of thousands of Poles who crowded around the platform. This raised the esteem of the Jews in the eyes of the Poles and raised the sense of pride of the Jews.

S_ [Ed. note: accurate name translation not possible as written in text: samekh-tes-reysh-vov-gimel-tsadek-apostrophe], a well known man of wealth from Oshmene, brought me into the center of the Party of Independents, set up by Pilsudski to bring the Jews closer to himself. This was a party without any obligation either to the right or to the left. Its sole aim was to work together with the government. I represented Divenishok and I was consulted on town matters more than the “Wojt” (head of the council) Motskowitz.

Most of townspeople were poor. They roamed around the surrounding villages buying produce from the farmers to sell in Vilne. It was said about Divenishok: “Divenishok of the forty beaters”, meaning that the town had forty horse owners, known as “beaters” because they whipped their horses.

*

Divenishok was charming. I loved it because of the enchanting landscape and its delightful people. Every one was attached to tradition, even the irreligious. I remember an incident concerning Sholem Yakov Alkanitski, whose 19 year old son Aharon came down with pneumonia and whose condition was very serious. Despite the fact that this Sholem Yakov was a devout communist he wrapped himself in talis and tefilin and in the middle of the night ran to the synagogue, opened the holy ark, kissed the holy Torah scrolls, prostrated himself before the ark, wept bitter tears, and implored mercy for his son.

To my great sorrow I was unable to fulfill my duties for long in Divenishok. The Poles, who were saturated with venomous hatred toward the Jews, and could not tolerate a Jewish physician serving in such a high position, began to undermine me; they sent petitions to the government opposing a Jew serving as “sejmikowy physician”. A Polish physician named Raszko was especially out to get me. He was a landowner in the vicinity of Benakani who was eager to take my place. He organized a venomous propaganda campaign against me and, since he had connections with the land-owners, he had great influence with the authorities. This Raszko was not a certified physician. At most he had completed some sort of school for “feltshers” [Tr. note: old-time barber-surgeon (cf. Weinreich), or assistant surgeon (cf. Harkavy)], but, as people said, he was an unadulterated goy and a great anti-Semite, and that was what was most important. I became convinced that it was not worthwhile for me to remain in Divenishok. It was with great regret that I left the town. I decided to go to Vienna to qualify as an ear, nose, and throat specialist.

In 1939 I enlisted in the Polish army and fought the Nazis. When the Nazis occupied Poland I was in labor camps in Slonim and Bialystok. Some time before the end of the war I went out to the village of B_ [Ed. note: possibly Benakani] disguised as a Christian, and worked in the sawmill. Everything that happened to me in that period is recorded in Isaac Nimsevic's book “For Their Sake – Likenesses from the Journal” under the heading “Secretary to the Gestapo – A Jewish Partisan” (published by the Ministry of Defense, January 1968).

When I reached Israel I joined the war of independence and was decorated by the state. I also joined “Mission Kadesh” as a doctor in the army hospital. I was decorated both for fighting for the state and for fighting against the Nazis.

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Dieveniškės, Lithuania

Dieveniškės, Lithuania

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 05 Jul 2018 by JH