[Page 409]

Seventh Chapter:

The Zionist Movement

[Page 410]

[Blank]

[Page 411]

The Beginning of Chibat-Tzion[1] (1886)

Translated by Libby Raichman

A

On the Saturday night of the weekly Torah portion “Lech Lecha”[2], the leaders of the Chovevei-Tzion[3] movement assembled in the prayer house of the philanthropist Mr. Yisrael Papierno, to consider all the work that was done for the benefit of the association, in the past year - the first year of its existence. In his address, the speaker Abromovitsh, spoke about the negative situation of the Jewish people among the nations, and he called upon the audience to participate in the grand plan of settlement in the Land of Israel. After that, two musicians from the school of music (Affere) who were present, went on to the stage and sang the prayer “El malei rachamim”[4] to the soul of the righteous minister Moshe Montefiore, and to the souls of the accomplished writers who cherished the holy plan – Peretz Smolenskin and Dovid Gordon.

Mr. Ashpiz, a representative of the association, presented an account of its income and expenditure for the whole year, to all those gathered, and after him, Mr. Fried read out the protocols of the organization, and the last letter from the Rabbi, the Gaon[5], Mr. Shmuel Mohiluber. In total, 403 Rubel was collected during the year, of which 200 Rubel had already been sent to Dr. Pinsker in Odessa, 150 Rubel was currently in the hands of the representative, and the rest covered increased costs and other expenses.

The leaders of the organization were of the view that their activities were still limited because most of the members were minors and young men. They suggested that if they were joined by people who were eminent and those of means, then the income would increase sevenfold. They decided to bestow honor and show respect to the elderly, for that is surely what was done when the position of chairman was given to the elderly wealthy man, Mr. Yisrael Papierno. The leaders of the association were people of integrity and there was no need to doubt their devotion to providing for the needs of the organization.

Now it is appropriate to welcome everyone who wants to be counted as a member of “Chovevei Tzion”; and may the wealthy among us, follow the example of the honored elderly man, participate, and be in the forefront of the activities of the organization so that the old and the young will always be with us, and increase and expand the deeds and activities of the group.

Eliezer Liezerowitsh

(“Ha'melitz” 1886, edition 150)[6]

B

The 18th December – this serves to inform the readers of “Ha'melitz” so that they will recognize and know, the shame and disgrace that Chovevei-Tzion endured in our town from the ignorant, self-righteous, and more than that, the pseudo-educated sectors; I will relate what happened last night. The preacher Mr. Abramovitsh acceded to the request of the leaders of the organization to speak in the large synagogue, on the subject of settlement in the Land of Israel, because we knew from his sermon on the 5th day of Mar-Cheshvan[7] that he would express himself in a knowledgeable and pleasing manner, that his words would be informative, and will achieve its objective. The news spread quickly throughout the town because of the notices that were attached to the walls of the prayer houses. Men and women came to hear the words of the impressive speaker. However – unfortunately for us – our good intentions did not materialize. Two leaders of the synagogue B. H. – M. G. and together with them, also one of the educated members of the community, who said that he has great knowledge on matters of income and economy, expressed their anger because we did not consult them, and they rebelled against us. They did not allow us to put our thoughts into action and poured shame and disgrace on this sacred plan in general, and those involved with the plan, in particular; and the people scattered, everyone returned home bitterly disappointed. Oh! The shame of it!

After I began to expose the villainy of these people to the readers, I will also relate, that after the meeting of the “Chovevei-Tzion” association on the 5th day of Menachem-Av[8], that was held in the synagogue of the Gaon Yisrael Papierno (chairman of the association), a memorial service was held for the accomplished writers Moshe Smolenskin and Dovid Gordon, may their memory be blessed. The people gathered in groups in all the synagogues, and each person expressed his opinion, because this time, before the Messiah comes, there will be those who will have greater audacity to take the Torah scrolls in memory of notable atheists, about whom we can say, they lessen and do not enhance ….

(Ha'melitz” 1887, edition 28)

Translator's Footnotes:

- Chibat-Tzion – the name of the organization means “Love of Zion”. Return

- Lech Lecha - is the name of the third Torah portion in the book of Genesis. Return

- Chovevei Tzion – means Lovers of Zion - a movement to build the Land of Israel that preceded Zionism. Return

- El malei rachamim – are the first words of the prayer for the dead. They mean ‘God, full of compassion’. Return

- Gaon – a genius, a learned man. Return

- Ha'melitz – the first Hebrew newspaper to appear in Russia – founded in 1860. Return

- Mar-Cheshvan – the 8th month on the Hebrew calendar, also called Cheshvan. Return

- Menachem-Av – the title of the month of Av, the 11th month in the Hebrew calendar. Return

[Page 412]

In the Days of Unrest 1891

Translated by Libby Raichman

In Bobruisk, two organizations were established to buy property in the Holy Land. One was founded by the lawyer Mr. A. Sh., who with his pleasant manner of speaking, was able to awaken this idea. Twenty wealthy men signed the document that required every member of the organization to contribute 300 Rubel to its treasury. Half was to be paid when their delegate returned from the Holy Land with precise information about the plot of land that he was designated to purchase. The second half – to be paid two years from the day of purchase. The second organization was founded by the rest of the residents of the town that numbered up to one hundred; each one of its members was required to contribute 300 Rubel: 200 after the purchase of the land, and the rest of the money was to be paid at specific times. A deposit of 31 Rubel was also paid on the day that the donor signed the papers.

(“Ha'tzfirah” 1891, edition 101)

|

|

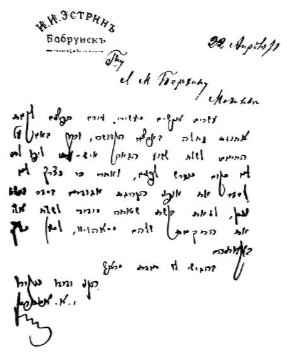

The printed/translated letter follows here below

22. 4 1891

In honor of

Mr. L. M. Barchin

Mohilev.

Twenty wealthy residents of our town want to purchase property in our Holy Land, and we are already prepared to sign and send a suitable person to Jaffa to find a place and set it aside for us. After that, we will need to organize the mode of leadership of our group and arrange correct governance. For this purpose, I request, my friend, that you send me your regulations from Mohilev so that we can follow your example.

I thank you in advance,

I, your friend, and admirer,

Y. A. Esterin. |

In The Group of Chovevei – Tzion

by Shmaryahu Levin

Translated by Libby Raichman

A few weeks passed from the day that I submitted my “supreme request” (that was what was accepted in those days), a request to join military work as a volunteer until the day that I actually commenced work. I had countless free time to pass, because I knew that soon, I would not have any free time at all, so I hastened to approach the youth of the town of Bobruisk and connect with them in a friendly manner. Of course, initially I approached the leaders of “Chibat-Tzion” in the town. Indeed, the power of connection is wonderful when one affiliates with people with a common goal, but particularly, the connection between the youth. From the first moment I felt at home in their company, as if I had landed among people who had always been my friends. Members from within the movement, the association of “Chibat-Tzion”, received me warmly, like an old friend.

There were three leaders of the movement in the town: Leon

[Page 413]

Luzinsky, Shlomo Fried, and Eliezer Leizerovitsh. The Luzinsky family was one of the most special and affluent families in Bobruisk. Indeed, when Leon Luzinsky's father and mother died, they did not have assets, but his relatives provided him with considerable support, and he was again able to earn a living with dignity. Leon was the first born in his family, and his two brothers and three sisters saw him as head of the family and its dependable leader. He completed high school, but because of his failing health, he was forced to leave his studies in the prayer house of higher learning. He was popular as one of the most enlightened young people in Bobruisk, but more than that, he endeared himself with his good qualities – his purity of heart and depth of spirit. He was a young man with a great mind, a sharp wit, but sometimes, also with cruel taunts and ridicule.

Shlomo Fried was an educated person, with a brilliant knowledge of the Hebrew language, but he did not rise to greatness, only to the point of writing letters to Hebrew newspapers, about country towns.

Leizerovitsh was a Hebrew teacher who was very successful, because of the level of mediocrity of his colleagues in the teaching profession. He came to Bobruisk from Borisov where people complained about him, that he was involved in many misdeeds, issues that clung to him, but no one knew what these issues were.

These three people were enthusiastic Chovevei Tzion. Leizerovitsh, the most difficult and stubborn of them, wanted a Jewish state in any shape or form, Fried clung to fine rhetoric, but was inclined to compromise, only if he succeeded in expressing his rhetoric. The most profound approach to the Jewish question, emanated from Luzinsky. He was an expert in Russian literature, as well as world literature, as long as the latter was translated into Russian. He did not find his way to Zionism in the usual way, through Hebrew education, rather through a process of general education. There was a dignity about him, in his person, and in his relationships with others, something that stood him in good stead – without bowing to others or lowering himself in their presence. His censure of assimilation was witty, and as sharp as a blade. He did not give his opinion regarding the practical difficulties of assimilation at all, but discussed his theories, in which he saw disgrace and servitude. In his view, assimilation was a kind of self-admission by the Jewish people that they were of an inferior level, that arose from a tendency and a desire to imitate. He felt that there was no injury more serious than this, to the feeling of pride that was in his heart, in all his being.

I do not know if it was his dignified disposition that induced his nationalistic view, or on the contrary, if his patriotism influenced this dignity. Be that as it may: the quality of his character made a deep impression on me that could not be erased. For me, he was the first Jew, self-conscious, a proud Jew, who saw his patriotism from a general human aspect that spoke in favor of Israel, not for all its glorious past and many enterprises. “Let's say” – Luzinsky would say – “that we are like all other people; let's say that the big wide world did not inherit a legacy from us, not great assets, nothing; does that mean therefore, that our right to life has expired? That we are by law, not entitled to acquire the primary, simple, right to life at the cost of exceptional deeds and enterprises?”

This way of proving our rights was new to me. Until now, I was used to demonstrating our right to exist referring to the greatness of our ancestors, and our historical deeds in the past; when I heard from this man, his proof and logic regarding our rights, I felt that I had been enriched with great wealth. Again, I am not obliged to pay for what happened in our past, the past is a precious asset of mine, a kind of iron-clad reserve fund that was not for daily use.

My new friends heard from the group in Minsk that they could use me as an outstanding speaker for publicity. Leo Luzinsky took me to the house of his uncle Yehoshua Luzinsky, whose daughter was engaged to Luzinsky. About fifty young people came to the house – for a secret gathering, of course. Luzinsky spoke first and I had to speak after him. I was very impressed with the way Luzinsky spoke about the issues regarding Israel, but I was unable to suddenly change in a way that was acceptable to me. In the meantime, I was still attached to my old pattern of presentation – to speak with pride about our past and our enterprises, and to convert in the spirit of the time, to the concept of ancient Israel and of the national choice of the Land of Israel. In such a speech, it was easy to include a great deal of enthusiasm and excitement and I used this opportunity to do so. In the first moments, I already felt that there was a relationship between me and the audience. A feeling of calm enveloped my being, and I felt confident in myself and my speech. These thoughts sustained me, my spoken language and reached my audience. I spoke for approximately one hour, and when I finished, I sat down at my place, and I felt the way a hero surely feels, that has just won a great victory in a campaign.

(From “Memories of my Life”, Book 2.)

[Page 414]

The Sale of Zionist Bank Subscriptions 1899

Translated by Libby Raichman

Since the second Zionist congress, the Zionists in the town were busy gathering signatures for subscriptions to the bank. During all that time, they managed to sell only six or seven hundred subscriptions, mostly, to approximately 50 people. When this came to the attention of the preacher Aharon Meir Drogitshin, he completed it, and brought the number of subscriptions to 1000. And the 300 subscriptions that he added were greatly appreciated and were divided among 300 people, one subscription for each person. These signatories were people who enjoyed the fruit of their labors and ‘by the sweat of their brow they ate their dry bread’[1]. And the money of the few wealthy who live in the town, lay idle.

(“Ha'melitz” 1899, edition 104)

Translator's Footnote:

- A quotation from Genesis chapter 3, verse 19, signifying the importance of labor to provide for one's needs. Return

Chaim Moshe Luzinsky

Translated by Libby Raichman

Chaim Moshe, the son of Naftali Hertz Luzinsky, was born on the 14th Tishrei 5634 (1873). In his early childhood he was orphaned by the death of his father and was educated under the influence of his mother who was very religious. His traditional Jewish education left him with traces that could not be erased. Until the end of his life, he remained faithful to his religious beliefs. Initially, he educated himself in the Gimnasia in Bobruisk, and after that in Slutzk.

Avraham Bakal of Bobruisk relates – “he completed his studies at the Gimnasia in Slutzk with great success, one of the outstanding students. However, his observance of the sabbath in its most minute detail, restricted him and he did not receive a gold medal, because he was not willing to exchange it for the medal of Judaism, under any circumstances. In all his days at school, including the days of examinations, he never desecrated the holiness of the Sabbath and the festivals, not in writing and not in drawing, and this did not please his teachers.” When he completed his studies at the gymnasia, he went to Berlin to study at the Rabbinical school of Rabbi Hildsheimer. At the same time, he took lectures in philosophy and economics at Berlin university. After two years in Berlin, he was accepted into the Institute of Law at Kiev university and completed his Law degree in 1901. During his studies, in all his free time, Chaim Moshe Luzinsky devoted himself to the study of the literature and history of Israel, and unrelentingly, to practical work for the Zionist movement.

Due to his fervent love for the Jewish people and his dream of revival in the Land of Israel, Chaim Moshe Luzinsky immediately occupied a prominent place in the Political Zionist movement, as a tireless worker with boundless devotion to the Zionist ideals. He participated in all the congresses. With the establishment of a bank for funding the building of Jewish settlements, he travelled to London and through his efforts, he garnered great benefits for the bank. In Kiev, Dr. M. Mandelshtam alerted him to a complex and responsible issue – the management of the financial center of the Zionist organization in Russia. In the town of Minsk, (in the absence of M. Mandelshtam), Luzinsky appeared as a lecturer on behalf of the financial center. In a general way, he merged his intense belief in the success of the idea that was so close to his heart, with his gentle and emotional character – great strength and love of toil. Despite the demands of his Zionist activities, he found the time to study subjects that were of interest to him. He had an incredible knowledge of philosophy, modern literature, both general and Hebrew literature.

“More than that the deceased was a calm enthusiastic Zionist” – writes Bakal – “he was a true Jew, concerned about religion, observant, comfortably fastidious, and serious. He also excelled and should be marveled at, for his good heart and his pleasant disposition. In short, in the soul of the deceased we chanced upon one who hosted: high education and complete faith, observance, and every good and true virtue.”

Luzinsky was devoted with all his heart to the Zionist movement – he rejoiced in its success and was disheartened by difficult inter-personal relationships. When an upsetting clash occurred between Achad Ha'am and Max Nordau, Luzinsky was so depressed

[Page 415]

by this incident that he became ill. It is difficult to describe how disturbed his Jewish heart was because of these terrible events of the past summer.

The terrible tragedy (disturbances in Kishinov) that was so severely inflicted on his people, caused him indescribable mental anguish. Perhaps this mental turmoil was reflected in the state of his health and aided the progression of his illness that prematurely ended Luzinsky's young life.

Luzinsky died on 25th Kislev 5664 (1903) aged 34, after a short and difficult illness. For a long time, the town had not seen such a huge attendance at a funeral. Thousands accompanied this man who fought for the eternal ideals for Israel, to his last resting place.

The mother of the deceased donated 10,000 Rubel to charity in memory of her son; 1000 Ruble to the National Library in Jerusalem. The local Zionists proposed to eternalize the name of the deceased by establishing a special wing in the National Library in Jerusalem in the name of Ch. M. Luzinsky.

(“Yivriskaya Z'izn” 1904, edition 1, pages 223-225,

And “the Mizrachi” edition 5, pages 383-384)

[Page 423]

“The Workers of Zion” in Bobruisk

by Mikhel Margolin

Translated by Odelia Alroy

A. Poale-Zion of Bobruisk (Youth)

The youth organization “Poale-Zion” [Workers of Zion] in Bobruisk numbered several hundred young boys and girls between 15 and 18 years old—an excellent group who were eager to learn whatever was taught in the self-educational clubs. Elihu Naiman, who was the leader of the organization, stuffed the material used for overshoes, was an intelligent worker, a good speaker and he was good at organizing the youth, but when it came to political activities, the director was the “private committee” which was waiting for instruction. The organization was divided into groups which would meet separately several times a week except for Shabbos, when there would be general meetings. During the winter the meetings would take place in homes, in summer in the field or forest, outside the city. It was nice to see how the young people would go to the meeting places after lunch on Shabbos, on the other side of the Berezina, among the hay fields. They would get to the river, rent small boats, for 5-6 people and row across the river -and then they would first go a few verst on foot until they reached the spot. They sat in a circle, some would lean against the trees and the meeting would begin. Between speeches there would often be singing. They would sing softly as is fitting for groups that do their work secretly. They were Jewish songs, revolutionary songs by Avrom Reisen and H.D. Nomberg. Reisen's song was very popular:

“Roar, roar harsh winds

Now is your season.

The winter will not last long

Summer isn't far.”

It is understood that we interpreted the song as we wanted: Now is the time of harsh winds—

arrests, deportations, hard labor but summer is not far—the revolution is coming. Just the same, there was little concern with revolution in the first days of “Poale Zion.” The main work consisted of spreading the ideas of Labor Zionism.

B. Elections for the Zionist Congress

At the time of elections for one of the Zionist Congresses a fight broke out between two candidates—Levkovitch and Elihu Naiman. Both wanted to go to the Congress and both were deserving—at the same time as that issue, another question came up: will the Poale Zion of Bobruisk be allowed to vote or not? Levkovitch's side argued that they wouldn't —they were too young and they would not be allowed to go to the ballot box. Elihu Naiman and his backers argued the other way, that the Bobruisk Poale Zion would be given the right to vote. Both Levkovitch and Naiman were understandably not so concerned with the good of the “Poale-Zion” of Bobruisk. It was known that the “Poale Zion” of Bobruisk would vote for Naiman.

C. General Poale-Zion

The General Poale-Zion considered itself as one of the strongest Jewish labor organizations in Russia. It had its dedicated activists-workers and intellectuals. The Bobruisk branch—about three or four hundred members—was divided into independent groups of ten members in each group. At the illegal meetings of the groups which devoted themselves to education, they studied economics, cultural history and Jewish history. If anything stuck to the students from all the learning, I'm doubtful. Tired after a full day's work and dragging around in the exchange in the evening, they had little strength to concentrate on the lessons. But to prepare some twenty odd residences for all the groups, and we had to change locations each week, because we were afraid of being caught-and preparing some twenty odd teachers was enough hard work and required much effort and exertion. I remember that in the winter days, dressed in a white jacket and boots, with a stick in hand, I was running around looking for locations. Only in the house of Moshke Miliniki and his two sisters, the bakers, did we have a steady meeting place. Aside from that, we had to run around from one teacher to another, giving them the addresses of the meeting places and the lesson plans of the students in each group. All had to be done secretly-we must not fail.

After an entire day tramping through the Bobruisk mud, I would return home in the evening and fall asleep exhausted.

D. Putting together the Secret Committee

The self-education group scheduled secret meetings, which were appropriate for the individual groups. From the leaders of the secret meetings they would put together the secret committee.

It was one of the hardest assignments. The electors were not allowed to know who had been elected. First they would select a trustee as head of the committee, who was in fact the leader of the organization. Every “secret meeting” sent a representative to the electors. The elections were held in the following manner: each elector wrote the name of a party member who he recommends as a member of the secret committee on a piece of paper and gave the paper to the trustee. That way the trustee was the only one who knew, by the papers, who was elected to the committee. The members, who participated in the secret meetings, didn't even know who was selected from their ranks as electors, because the selections were made in this way. The participants in the secret—meetings wrote the names of the candidates who they proposed on notes and secretly gave them to the trustee, who would tally the votes, and according to the count, write down who was in the group of electors.

At that time, when Yankel Paritsher—a student—was the trustee, it happened that a friend at the time of the voting of the secret committee, didn't write his name on a note, leaving it to Yankel to decide on a candidate in the committee. I was the youngest member—just a boy—and for the first time I felt lost among the older members, active party members, workers and students.

E. The Exchange

The larger the organization, the more important it was, the bigger part of the main street it occupied. The “Bund” which was at Muraviavska St., was the largest in Bobruisk. It stretched from Belinsky's porcelain business until the Turkish bakery, noisy and lively. The other side of the street, from Barash's Pharmacy until the end was occupied by the “Poale-Zion.” Later it transferred to Shosi St. The exchange was the vital nerve, the pulse of each party. This was the place of discussion, meeting, debating about ideas and work conflicts and sometimes getting even with whomever one needed to. An organized group was always there, ready for whatever.

People walked back and forth, up and down, in the area of their exchange, talking, screaming, droning and it seemed that the street was swarming in one bi beehive. And if a Poale-Zionist wandered into a Bundish exchange or in reverse, he'd be surrounded by a group who would try to convince him, loudly with quotations from books and speeches, which one had never seen or read, that his party is correct and the others not.

And if it would happen that the Bundist couldn't counter the Poale-Zionist, he'd let out with a proven weapon. Even Nardov himself couldn't find a difference between these points and so forth, which was enough so that the “enemy” would give in.

The exchange was also popular with the police. They knew each one and they knew to which group he belonged and they guaranteed that there would be no getting lost.

F. Illegal Meetings

Because of the constant lurking danger by the Czarist spies, we had to conduct all party business in secret and all meetings were organized quite stealthily. That wasn't easy. To organize and conduct general meetings with the participation of a hundred people, or an assembly of two parties (often between the Bund and Poale-Zion) in order to discuss a joint activity or a discussion of ordinary problems the organizers needed to show professional talent, not only for secrecy, also security and stealth. The most important was to choose such a house for the meeting, which had many exits and was in a labyrinth of streets. Such houses are most often in the outskirts, the poorest part of town. There in a carpenters shop, which met the requirements the general meetings would take place.

For security, we would begin the meetings by telling the people that if there should be a slip, they shouldn't be afraid and get into a panic, but each should say that he came accidentally, because someone had invited him, but he didn't know what for.

The person who took upon himself the responsibility for everyone was Chaim K. I remember that I was jealous, that he was given the privilege to be the sacrifice for everyone. Once I asked Chaim to give me the responsibility to be the scapegoat. He looked at me with sad, fatherly eyes and said: “Wait Mikhailke, your day will come. You will bear the burden of responsibility. Meanwhile it's too soon for you.”

Aside from the shops, we would also hold meetings in the barracks. That was the good idea of some of our members who lived near the barracks and saw how they empty out, when the soldiers leave for maneuvers in the summer. The members decided to use these empty barracks for Poale-Zion meetings. In order to make them more secure, we would station patrols the entire way from the barracks to the police stations. There were quite a few couples in the organization. It was not secret and they would stroll in the streets and enjoy each other—each couple had a pair of boards and in the event of danger, a show of police or soldiers on the way to the barracks was enough for a couple to start clapping the boards, and as quick as an eye blink the signals went form one couple to another until it reached the meeting. Upon hearing, the people assembled would disperse orderly in the streets, and when the police arrived, there was no trace of the meeting. More than one discovery by the police was averted on account of our loving couples, who the police never suspected were guarding the illegal meeting.

G. Meetings in the Forest

In summer we would move our meetings beyond the town into the forests. Some members would locate a suitable place in a nearby wood, which we could approach from various sides. Shabbos , after lunch, we would leave the town on the pretense of strolling in the woods. The guards would climb the trees and suing binoculars watch in the direction of the town. Once, in the midst of a meeting, the guards sent an alarm that police and soldiers are approaching the wood.

Those at the meeting then decided not to disperse and not to spread out into the forest via the secret passageways and paths, as usual in such an event, but instead in an organized fashion to oppose the police and set tows—the girls in the middle—armed with sticks we set out back to town, opposite the oncoming police. Some of the intellectuals who were with us, proposed running away, because they would have suffered more by an arrest than the rest. Btu they relented. We approached the police and the police approached us. We were almost ready for a war to break out…suddenly to our great amazement, the police turned their backs on us and marched into town. What was the reason for their going back remained a mystery. On the way, the police beat two members and arrested several others. In town, the news had already spread, that the meeting was uncovered and they awaited us in chains. When they saw us coming with a police guard, healthy and lively, they rejoiced. The pair arrested were freed the next morning.

In general, very few meetings fell through. If not for the spies, the police would never have traced our secret work.

H. Fighting Groups

The fighting groups, a decided group in the organization, had its own laws and discipline. Not everyone was deserving of being taken into this very secret group, which carried out one of the most important functions in the activities of the organization.

The fighting groups would capture members arrested by the police; while they were being transported, get even with strikebreakers and “teach” the bosses.

I remember a piece “of work” by the fighting group, during a strike by the pharmacists. All the pharmacy owners gave into the demands of the strikers, except one, a Pole. It was a beautiful evening, the sun had not yet set, but the street was empty. My friends and I were wandering about the exchange. Suddenly a member of our group, Reuvke, came over to us and whispered a secret to each of us that we should leave here as quickly as possible. In a while we heard the shatter of glass—that had been done by Reuvke and his friends, breaking the windows of the Poles pharmacy. By the time the police master and the Cossacks came, there was no trace of Reuvke and his gang.

The police master was angry, cursed, but it didn't help. The perpetrators weren't caught.

The pharmacist after this episode was no longer stubborn and gave into the demands of the strikers.

I. The Self Defense Organization

The self-defense, as opposed to the fighting groups, was a broad based organization. Nevertheless, the fighting groups were the heart, the foundation of the self-defense. The Bobruisker organization was armed with a few old guns and small bombs, which were never used. The bombs were stored in the Slobodka Talmud Torah in the attic. A spy told the police the spot and the gendarme came especially from Minsk to uncover the arsenal.

Fortunately, the fighting groups had removed them the day before—indeed just one day before—no more, they had taken them to another spot and the gendarme was disappointed.

What happened was that at first they went straight to the attic where they found nothing and so they tore apart the walls, destroying the whole roof. But the bombs weren't there. They left Bobruisk angrily.

We, the youth of the self-defense group, would get up each morning before daybreak and would travel far beyond the town to learn how to shoot the old guns. We would gather in the hayfields where no one saw us and we would set up a board and take aim at it or a tree. Bentche Rachlin was our teacher. Where he learned how to shoot, no one knew.

It seemed like a child's game, but we took it seriously and diligently learned how to shoot. The force that led us to organize ourselves in a self-defense group was the Kishinev pogrom, which shook us all to the depths of our souls. Different rumors spread about the destruction of the community, one worse than the next. We felt a shame and a sorrow that we had not opposed the pogrom makers, that we allowed ourselves to be slaughtered like sheep. We very much wanted to get even with those who made the pogrom—kill them and show that we can fight. And when a short time after the pogrom, Chaim Nachman Bialik published a poem that made a strong impressing. Bialik accused us, the young people of cowardice in sticking out our necks to the executioner. Bialik's poem worked better than one hundred agitators—it woke in us national self-worth and urged us to fight for our lives. It also had a strong effect on the citizens. They began to treat us with respect and were drawn to us. The saw a point to us, and the wealthy began to support the fund for self-defense.

J. Zubatovshtshina

The Zubatovshchina movement got its name from its founder, Polkovnik [Colonel] Zubatov, who was chief of the Moscow police force. His plan to form a new workers organization, which would fight for economic rights again the exploiters, was a well thoughts out plan to diver the working masses from the political battle against Czarism and to snare the workers in the police net. Outwardly the movement seemed to be innocent and logical. Indeed many workers, devoted and honest activists, turned to this group.

Zubatov promised his followers: help from the government, improvement in the economic situation of the workers, help for the strikers in their battle for better working conditions. He only demanded that the battle carry only an economic character, that is, halting the political battle against Czarism. Then the movement would get all the privileges of a legal organization.

The Bund came out with a warning not to be taken in, led a thorough discussion with the supporters of the new workers movement. But it didn't help. They were dazzled by the first well-organized aims.

In Bobruisk the union of clerks—a few hundred people—joined the Zubatovtze side and they immediately declared a strike. It was a shame to see how the leaders of the strike rode around with the police master in one wagon, protected by the police and they carry on a strike.

The police kept their word. They supported the strikers. Members of the revolutionary parties looked at this spectacle with disappointment and gritted their teeth. The strike was led with a heavy hand, with terror. At Belinsky's porcelain business, they broke several cartons of porcelain and the police stood by silently.

At the end it came to pass as it had to—as had been planned. When the strikers began to win in the economic battle, the police stopped the incendiary acts and went to the side of the bosses and then there was a conflict between the Zubatovtzes and the police. The strike was over and there were arrests. Who the activist were, the Czarist agents now knew…. The organization fell apart and a number of the members came over to us, the Poale-Zion, and some to the Bund.

K. The First Demonstration

The committee of the Poale-Zion party decided to organize a protest demonstration on the anniversary of the Kishinev pogrom. All the members of the Poale-Zion were requested to come to the big shul on Shosi on Shabbos morning and to pretend that they came to pray. After prayers, when the congregation would start to leave for home, they would lock the door and not let anyone out. One of our comrades would go up on the stage (bimah) and talk about the Kishinev pogrom. After the speech, we would go onto the street, on the Shosi, and demonstrate. The town was sunken in mud and the Shosi was the only place where it was possible to have a demonstration.

The plan was carried out just as it had been thought out. At about 10-11, the comrades started to gather in the shul. Those praying wondered why so many young people had come to pray and took pleasure in that. The crowd was in a holiday mood. When they were finished with their prayers and wanted to leave, some strong young men blocked the exit and asked the people to wait—and by the time they looked around, one of our comrades was already on the stage, rapped the lectern for the quiet and began his talk. He talked about the Kishinev pogrom, about self-defense, mentioned Bialik's poem and the crowd was confused, not knowing what was happening. Some were angry; some were pleased by the antics. After the speech, the doors were opened and we went out first, planted ourselves on the Shosi, unfurled the flags and started singing, as we march onto the street. We went in set rows and the crowd around us grew bigger and bigger, encouraged us, clapped “Bravo.” We were smeared with mud, from our heads to our toes, and like agitated devils, we marched through the street. Several comrades took guns out of their pockets and began shooting in the air, in order to liven things up, and it was lively. That is how we marched for a half hour. Suddenly from nowhere, Cossacks appeared and began to beat us with whips, chasing us into courtyards and we fled. Comrades hid wherever they could: in courtyards, over fences and they scattered in all corners. There were no arrests that I can remember. We only were very frightened.

That was the only demonstration I took part in. I ran home. Old man Rendel already knew everything and when I came home sweaty and tired and caked with mud, Rendel came over to me. Not harshly, not punishingly, but fatherly, even with humor. First, he decided that I should change my clothes, freshen up, clean the mud off my boots and calm down—today he is not letting me out of the house. I can do whatever I want: lie down or go to work. And if the police come to ask for me, he'll say that I'm sleeping or working. I listed. How I listened!

The demonstration was wonderful. Everyone talked about it. Everyone like the idea of meeting in shul, locking the door and not letting the congregants go home—that worked. The police were annoyed: an unheard of scandal—to pull it off right under their noses and to have a demonstration with flags, with song and even shooting and no one caught in the middle of the day.

In the evening, the “Bund” organized a demonstration on Muriavoskva St., but it wasn't successful. Only a few people participated in the demonstration and the effect was small. Understandably, we teased with the Bund and threw it up to them, that they couldn't organize a demonstration….

L. The Opposition

Every party had an opposition. It was enough for a few dissatisfied people to get together—and there was an opposition. And the opposition would be organized with all the details of a proper organization: with its own committees, its own meetings and its own leaders. It was in short; an organization with in an organization. At that time I participated in the opposition of the Bobruisk, Poale-Zion. It is understood, we also had demands. The requests were very “original” no more, no less.: “Down with the white collars and cuffs.” We couldn't think of anything smarter, so that was the issue. In reality, the reason was because of other things, pure and simple. We went about pompous, unhappy and with complaints for the committee: “What do you mean, such work is going on and we, the poor masses, don't know about it.” When there was no important news, “no revolutions are carried out silently.” It never even occurred to us….life was always secretive and that led us to think that something was always brewing….. Something was always happening that they are not telling us about and we wanted to know it all. We didn't want anything kept from us. Curiosity raged and the thirst for secrets was great. In truth, the committee people didn't have secrets—and their replies, their swearing that they have nothing to tell worked like oil on fire. The more they answered, the less they were believed, and the more they answered. In short, our opposition grew. We had the majority of the organization. We would hold separate meetings. We had a separate committee—and the main point—we also developed a conspiracy. And when the opposition group declared, down with the white collar and cuffs, it was an opposition within an opposition. …In a word, our committee began to negotiate with the committee of the organization. In truth, we didn't even know what to negotiate about. But it was an opposition, we tried to negotiate, evening after evening we had meetings, which lasted a long time. Eliezer Shine was the leader of the committee, a loyal Jew, a scholar, but with all his learning, he accomplished little. His opposition was as strong as iron, and there was nothing to be done. I remember certain evenings when we had long discussions and fiery debates and didn't resolve anything, so we began to demand there be a vote as to whether we should maintain the opposition or give it up. There were comrades, who thought we should give up the opposition and make peace with the committee. So we voted and it came out that the majority wanted to retain the opposition, in no way to abandon it. After the election, when Eliezer Shine saw that he had lost, he asked for an opportunity to say a few words, before he pared from us. It is understood that his request was granted. He began quietly, soothingly and at the same time he was punishing. His words are etched into my mind “As you know—he began—I am a strong believer in the Torah—all that Moshe, our teacher, wrote in the holy Torah, is right and clever. There are no extra words. There is no thought, which is incorrect. But I have one though that I can't get rid of. How each of you knows there are more fools than wise men. Sometimes, you have to direct a clever man when there are fools all around. When voting, you have to side with the minority that is the cleverer. Why our teacher Moshe sided with the majority is a mystery for me. I don't begin to understand why one should follow the majority “what the fools say” and he finished as quietly as he had begun.

A queer mood settled over everyone. The room was quiet. No one spoke, as though

Eliezer had given us a sharp blow, which made us mute. In the few minutes of quiet, we thought it over. I came to myself first, the leader of the opposition…. Ashamed, I went over to Shine and extended my hand, a sign that I give in—no more opposition! Others followed my example. There were those who were unhappy with our stand, screaming that we had spoiled it for them, but it didn't help. The opposition was broken.

M. The First Proclamation

I remember until today how they brought me the first proclamation, a single copy and told me that I should print a hundred copies to distribute among my friends—That was a proclamation from Yekaterinoslav.

How to print several hundred copies, I had no idea? After a long search, I found that one needs a hectograph. We were afraid to buy one so it came out that we would make a hectograph ourselves. We went to a friend, who studied with the pharmacist, and asked him to teach us to make a hectograph. He knew a bit and he learned a bit from the pharmacist or others and in short, he gave us the instructions for putting together the hectograph. First, we went to a tinsmith and put together the tin materials, next we bought gelatin; and other materials. We bought everything in a different place, in order not to arouse any suspicion. And, we made a hectograph, which worked very well. We got a bottle of special gold ink and some new feathers and we took to our work. Like religious Jews at the last prayer on Yom Kippur, we trembled before our holy work. We worked with special paper, decorated the top of the proclamation and began printing. We printed and put the printed pages all over the room so they wouldn't stick to each other and smear. We were almost done with our work and we felt so good: the first proclamation done with our own hands.

Suddenly— we were disheartened! We were discovered! On the oven, which was divided from our room by only half, a wall, sat the landladies daughter, her head stuck into our room and she is looking at what we are doing. My speech stopped from fear. What had happened! And the little girl winked impishly with her dark eyes and laughed. From fear I was unable to speak. I imagined what kind of fate I would have from my landlady! I'd at least have to find another room.

The landlady had an idea that we were up to something illegal. Our tiptoeing about, locking the room, hushing, had brought out the thought, and she sent her daughter to see what we were doing.

She gave us a lecture, punished us for going in such a direction: “You'll get caught in the end. And what will happen then? do you think they will pinch your cheek or pat hour head? What if your father and mother knew! They would…. meanwhile, I'll ask you to clean out this stuff. There must be no trace left.”

I obeyed—. I was happy that I got away with only a bit of fright. I was ready for a scandal. I thought she would throw my things out the street and that I'd have to look for another place to spend the night. It came out better than I thought it would. I got a lecture, heard the woman's big mouth, gathered my proclamations and all was quiet—just as though nothing happened.

N. Herzl's Death

Workers left their work, storekeepers closed their shops and everyone ran into the street. No one could sit in one spot, alone with their sorrow. They didn't want to believe that it was true. They ran to the Dobkins, to Yitzhok Isaac Estrin—one to another to ask, to be sure if it's true. No one wanted to believe it. Herzl died and the people cried. There was no way to console them in their sorrow. The crown had been torn from their head.

After 3 days they decided to hold a service in Bobruisk in which the whole town would participate. But where would we find such a risky place to hold the whole town? In the cemetery on the outskirts there was an empty field and on that field they would hold the service. It was announced in the synagogues that everyone should come to the field where they could pay tribute to the great Herzl. And that is what happened. That day the whole town gathered on the field. Everyone went. Old and young, man and wife, school children in set lines in a sorrowful procession. Even the poor women, the beggars from the outskirts, wrote a sign of mourning on a piece of torn sheet, tacked to two poles.

In the midst of the memorial demonstration a friend came and warned me that the Bundists had come to the service and they wanted to demonstrate. I didn't want to believe it. That could lead to a bloody fight. I went to look for the leaders of the Bund. I found Nomke from Paritch and appealed to him, telling him this was not the place for a demonstration, but he answered me curtly “That's how it is going to be.” I went looking for other activists. I went to other friends, asking them not to provide, but it didn't help. The members of “Poale Zion” were also looking for a fight, like the Bundists. At the end of the service the Zionist leaders decided that since there was such a crowd at a Jewish gathering, we should say a blessing for the Czar. As soon as the Bundists heard Nicolai, they began to scream from all corners of the field in agitated voices: “Down with the Czar,” “Let there be freedom,” and other slogans of that sort. And before I left that tumult, I saw them beating up one another, the Poale-Zion and the Bund. The police had a chance to get involved in restoring order—and they hit both sides.

There were some curious developments at the time of this tragic incident. I remember how a member of the Poale-Zion was fighting with someone from the Bund and a policeman ran over to separate them. The Bundist stopped fighting and started screaming in the policeman's ear, loudly “Down with the Czar, Up for freedom.” The policeman, a friendly man, thought it was funny and started to laugh: “You are a fool—he said to the Bundist—why are you yelling at me “Down with the Czar.” Go to Petersburg and yell and if you accomplish anything in Petersburg, and change things there, things will be different. Don't be silly, go home, he appealed to the fighters. But it didn't help. They keep fighting and how they fought!

That is how the memorial for the great leader Dr. Herzl ended. The story of blessings the Czar angered everyone. A few people, wanted to ingratiate themselves with the authorities and that led to the fight. A few people were arrested and as usual in such instances, everything was done to free them, whether they were Bundists or Poale-Zion.

O. The Soviet Socialist Movement

The Soviet Socialist Movement, from its first beginnings, began little by little. Almost unnoticed, it began to spread its influence over the ranks of the Poale-Zion organization.

The ideas and territorialism found a way to all branches of bosses, citizens and workers.

The Poale Zion movement was for the most part swallowed up by Soviet Socialists, except perhaps in south Russia where the head of the organization was. Ber Borochov was the only bright star of the group. When the intellectuals, Syrkin and Yakov Leshchinsky at the head, stood up to the SS. they took the territorial stand. In Bobruisk there developed a lively activity in the SS.

I had a friend, Davidke Fialkov, from Pinsk. One day I began to notice that my friend seems to have a secret that he is hiding from me. Until we both met at a meeting of the newly forms SS. We then laughed at each other about our conspiracy.

P. After the Revolution

I returned to Bobruisk, returned to the exchange. Again among old friends, everything the same, but nothing the same. Things were quieter—not what it had been. The noisy, turbulent life of a year and a half ago had disappeared. A large number of the comrades were swept up in the storm of emigration and left for big, rich America. The emigration wrecked the ranks of the organization. The best comrades left, fled—the ranks thinned. After the first great enthusiasm, there was a lull. The failure of the revolution was felt by all the revolutionary parties. The Poale Zion” movement still had momentum—but it was the momentum of inertia, from the strength which had been amassed in the good years. But the decline was beginning to be apparent. Boys and girls began to carry fiddles and mandolins, played music and looked for places to dance. The hot rivalry between the Bundists and Soviet Socialists eased. The exchanges became sparser; they had thrown off the pack of idealism; life became empty.

This material is made available by JewishGen, Inc.

and the Yizkor Book Project for the purpose of

fulfilling our

mission of disseminating information about the Holocaust and

destroyed Jewish communities.

This material may not be copied,

sold or bartered without JewishGen, Inc.'s permission. Rights may be

reserved by the copyright holder.

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Bobruisk, Belarus

Bobruisk, Belarus

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Yizkor Book Director, Lance Ackerfeld

This web page created by Jason Hallgarten

Copyright © 1999-2024 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 28 Feb 2024 by JH