|

|

|

[Page 365]

By Peleg-Marianska

Translated by Moshe Kutten

Edited by Jane S. Gabin

The will of the Pohoriles family in its Polish original is kept in the archive of “Yad Vashem” in Jerusalem. Only sections of the will are brought here along with the review by Mrs. Peleg-Marianska and with the kind permission from “Yad Vashem.”

The EditorThe Pohoriles family:

Emanuel Pohoriles, an agronomist, Ternopol District

Roza Pohoriles, the daughter of Herman and Regina Freudenthal, was born in 1891 in Aleksandrovka village, Skala province.

Hulda Pohoriles, the daughter of Emanuel and Roza Pohoriles, was born in Lviv in 1920.The entire family perished in Brzezany. May G-d avenge their blood.

A unique correspondence containing six letters was assembled in this article dedicated to the history of the Pohoriles family's Holocaust years. Three of the letters were written in April 1943, in Eastern Galitsia's town of Brzezany, by members of the Pohoriles family: the father Emanuel, mother Roza, and 23-year-old daughter Hulda.

These letters are the farewell compositions of people condemned to death. They all died in June 1943, three months after the date of the letters, during the final liquidation of the town's Jews. A copy of Emanuel's handwritten original will, signed by the three family members, is attached to the letters.

Another two letters, added to this collection, were written by a family friend, the Polish engineer Tzebinski, in 1946. He kept the material and sent it to their relatives in Israel after the War, as requested by the deceased. The sixth letter is an acknowledgment and thank-you to Mr. Tzerbinski by a family relative, Dr. Shvager, in Tel Aviv, for receiving that precious patrimony.

The letters of the Pohoriles family members excel in their shocking accuracy of the description of the slaughter waiting for them. Following the period of oppression and murders they had witnessed, they are heading toward their death with their eyes open, without a shadow of hope.

And here are some sections from these letters, translated from Polish:

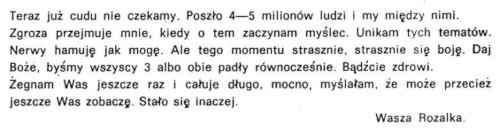

From the mother's letter:

“…Now we are no longer waiting for a miracle. Four to five million people, we included, are dying. I am haunted by horror and avoid talking about it. I try to control my nerves, but I am so fearful from that moment. G-d would ensure that all three of us, or maybe the two of us, die together … Be healthy… I say farewell with kisses to you. I thought that we would be able to see you again, but that will not happen...” Yours, Rozalka.”

|

|

[Page 366]

From the father's letter:

“…Do not forget… when the time comes for the negotiations about the peace, do not forget the millions who fell victim to the executioners. Do everything to take revenge for their... pure blood… These letters will be kept by noble people who helped us a lot and requested nothing in return. They will tell you when we were murdered and where we were buried…”

|

|

From the letter of the daughter:

“…We now stand in front of the gates of death and wait for it fully conscious, with no hope for rescue and mercy. Our will is strong to live and to get out of this horrific situation, to laugh at the whole world under the sunlight…and to live…to live. “We do not have poison because it is difficult to get it here, so there is no choice but to go by ourselves to our funeral, strip naked, stand face to face with our grave, and receive the bullet in our heads. It seems that I would go alone since Mother cannot march. They will 'finish' her at home, and the labor camp will wait for Father…”“We are waiting for 'it' during Passover when you pour your holiday wine – Here it would be the warm red blood…All of you be healthy, enjoy yourself, love, and don't bother yourself with nonsense. Today, I would also know how to live, but I understand it is too late. Now I know that everything is vanity…and spring is so wonderful compared to our horrific death.”

|

|

|

|

|||

[Page 367]

Special attention should be given to the Will of Emanuel Pohoriles, which contains a detailed list of the family's property. This is a typical list in its character and form. As an owner of an agricultural farm, the deceased counted accurately all the details. Among the details are the number and “private” names of the horses and the quantities of crops in measures customary to Polish villages, every tool, and agricultural machinery. All of that is listed with the indication of the monetary value at the time of the confiscation by the Soviet and German authorities. In the end, the deceased asked to divide the anticipated compensation between the engineer Tzerbinski and his relative in Israel.

The Will was written three months before the final Aktsia and testifies to the deep belief of the condemned to death in honesty and justice that will come after the War. Obviously, there is real meaning attached to that document but it also constitutes a precious human document.

Tzerbinski's letter contains information about the progress of the Aktsia in Brzezany in June 1943 and details about the fate of the Pohoriles family. According to the Tzerbinski testimony, all three were killed when their bunker, where they were hiding, was discovered. At that moment, Emanuel Pohoriles shot at the Germans, and after that, he shot his wife and daughter and then killed himself. The family's burial is in a mass grave, marked by Tzerbinksi, in a prominent location in Brzezany.

This bundle of letters, which was kept until the end of the War, was sent to Israel and handed over to “Yad Vashem” by the relatives of the Pohoriles family. It would serve as historical material and at the same time as a memorial for three among the million.

By Dr. Shimon Redlikh

Translated by Moshe Kutten

Edited by Jane S. Gabin

Our family resided at the edge of the Ghetto on Train Street, at the house of the Arauner family. The men worked in jobs provided by the Germans. Some of them worked in jobs of particular importance. These people were the owners of the letter W. The women, too, worked in various jobs.

Like in every house in the ghetto, hideouts (bunkers) were constructed in that house. The hideout, constructed before the Judenrein,

[Page 368]

saved the lives of several people. It was constructed as a double roof in the corner of the attic. It consisted of a limited space between two tin walls with a door located on the inner wall, which could be detected from the outside when closed.

About 40 people, almost all the house residents, entered the hideout on the evening of the Judenrein Aktsia. My father Z” L, Shlomo Redlikh, who was among the barrack's people, was convinced by his barrack friends that the Germans were about to conduct an inspection and that he had to be there. That was the last time we saw him. He was murdered a day later when the barrack's people were the first to be eliminated by the Germans.

On the day of the Aktsia, we heard the voices of those people who were taken out from their hideouts and led outside of the ghetto. There were three children and several elderly in the hideout, among them my grandfather Fishel Bomze Z” L and his wife, Rivka Bomze (nee Shvartz) Z” L. Since the hideout was small, people lay next to each other for three days. The food ran out, and the Aktsia lasted a few days. After a week, people began to exit the hideout to look for ways to be saved.

Only eight people remained in the hideout after two weeks: the owner of the house, Mrs. Trauner, her sister, Fishel Bomze and his wife, my mother Khana Redlikh, myself, and grandmother Flug and her nine-year-old grandson, whose parents left him with the grandmother to try to save themselves. Mother and Grandmother discussed what to do. In the end, it was decided to turn to a friend of the family, a Polish blacksmith, Stanislav Kadugni, who owed my grandfather a lot of money. When we looked through cracks in the window sill, we saw that he passed near the house several times. My mother and grandfather went out to that Gentile's home, several kilometers from the ghetto. My mother told us about that visit: “Grandfather knocked on his window, and the gentile immediately opened the door and got us in. We told him about what happened to us and cried. We asked him to help us with food. The gentile said he would help as much as he could. He gave us a pail of water, a few loaves of bread, and a sack of charcoal to prepare hot food.” My mother and grandfather agreed with Kadugni that they would come to him every two weeks on Tuesdays, in the middle of the night, to take food and water. These night trips became a routine.

During the following few weeks, Poles and Ukrainians entered the house below us, breaking walls and looking for properties and bargains. The house remained empty and half-ruined while we were hiding in the attic like ghosts inside the empty and destroyed ghetto.

Two months passed from the day we entered the hideouts when Mrs. Trauner fell seriously ill. She was dying for two days, witnessed by two children eight and nine years old. After her death, my mother and grandfather tied her body and lowered her down to the cellar. Her sister, Mrs. Trauner, left the hideout the following day. We were left with six people in the hideouts. Three more months passed.

On one of the days, we heard people who arrived at the house and came to fix the apartments. That lasted for several weeks. One night, my mother and grandfather went down and saw that everything was ready to accept new tenants. A question was asked then: how would they be able to go out and bring food, and in general, should they continue to live in a house populated by people? They consulted with Kadugni, and he stated that he could not provide shelter for us. In January 1944, when Mother and Grandfather wanted to leave on their regular night trip to bring food, they found, to their horror, that the door to the attic that led to the staircase was locked. They returned to the hideout and sat down. They spent the whole day trying to find a solution. Grandfather woke up the following day and opened the door with an ax. Our former apartment was located across from that door, from where a woman came out in panic. She promised not to snitch to the Germans but requested that everybody vacate the attic within a day or two.

[Page 369]

In the evening before the Judenrein, My mother's sister and her husband escaped to the village of Rai, and there they found a shelter with a Ukrainian woman farmer. That woman came to our friend Kadugni, and by that, the connection between the two parts of the family was maintained. When our house was reoccupied, Mother and Grandfather did not go to Kadugni, so my aunt began to worry, and she sent the Gentile woman every evening to find out what happened to us. The day following the meeting with the new woman resident in our former apartment, Grandfather went out in the middle of the day, and when he arrived at Kadugni, he found the Gentile woman farmer sitting there. Grandfather cried and begged the woman to save us. In the end, she agreed to take all six of us to her village. Kadugni did not let Grandfather return to the ghetto during the day. When my mother saw that her father did not come back in the evening, she decided to come down with me from the attic. We left the attic and stood in the house corridor by the window, where we could look outside. We waited there for about an hour, and when it became dark, we suddenly heard the steps of Grandfather. He said: “G-d is great. The Gentile woman agreed to take us today and the rest of the people tomorrow.” My mother took my hand and went out of the house. The Ukrainian woman farmer and Kadugni's eighteen-year-old son stood on the sidewalk near the house. We had to cross the lit street, where we could have been discovered and handed over to the Germans. The young man walked in front of us so that he could slip away in a moment of danger. The woman farmer walked about five steps behind us. While crossing the street, the youngster whispered to my mother: “Pray to G-d, pray to G-d.” When we crossed the street into the darker side, the woman farmer took me on her back (I could hardly stand on my feet from lying down and not walking), and she also held my mother's hand. We walked like that for six kilometers in the snow that reached a depth of about a half meter (about 19.7 inches). We left at 6 in the evening and arrived at 5 in the morning. My mother tripped and fell several times, but she rose and continued to walk. We both grabbed snow and drank it thirstily since there was a shortage of drinking water at the hideout during the last few days. The Gentile woman went out to the ghetto again on the following day to bring over the rest of the hideout residents to her home. However, young boys discovered them on the way to Kadugni's house and handed them to the Germans. They were undoubtedly beaten and tortured but did not tell the Germans about us.

We spent the next six months, until the summer of 1944, sheltered by the Ukrainian Gentile woman, whose name was Tanka Kontzevitz. Her husband was taken to forced labor camps in Germany, and she remained with her two children, a son, 6 years old, and a daughter, 10. We helped to sustain her by asking a Polish woman friend to hand over various items we had left with her in the past.

In the winter, we hid in a narrow storage shack, where only a single bed was placed. In the summer, we moved to a small attic above a cowshed. Gentiles and even Germans entered the woman's home often, and we feared that we were going to be discovered every moment. Our hopes grew toward the summer when we heard the voices of the approaching front from the east. However, it was then that the dangers rose. The woman farmer decided, several times, to expel us, but with tears and shouts, we convinced her every time not to realize her threat.

In July 1944, we finally received the news about the liberation of the city and its surroundings by the Soviet Army. We returned to Brzezany, which was empty of Jews. We stayed there for about a year, and in the summer of 1945, we moved to Poland under the repatriation campaign of Polish citizens.

By Meir Tuller

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

Edited by Jane S. Gabin

For the sake of knowing Each of us needs to be informed not only about the crematoriums (Auschwitz, Majdanek, Treblinka, Bergen-Belsen, Belzec, and all of the others), and not only about the ghettos and mass graves at the municipal cemeteries. All Jews all over the world must also know and remember the hundreds of thousands of Jews tormented to death in the Nazi forced labor camps that existed in eastern, Lesser Poland and, principally, how the German murderers reigned over and tortured Jews.

Three of the innumerable such forced labor camps where hundreds of young men were taken from out of the city and area and where they perished were: 1) Gawrielubka (Tarnopol camp), 2) Borki Wielkie and 3) Kamionka (train station – Bugdnubka). I will here relate how the drudgery looked, and the death in the forced labor camp Kamionka.

After all of my experiences and fateful trials in the ghetto, hunger, and death aktsias [actions, usually deportations], I was, yes, really the only Berezhany camp Jew who survived. A witness who by a miracle personally endured over and over again and survived the great tragedy that took place in the forced labor camp Kamionka, only one from among the hundreds. Places of hell, as if cut off from the world, fenced in by electric barbed wire, tormented and starved to death, approximately 10,000 Jewish men from eastern Galicia, including a very considerable number of fellow townspeople.

During a smaller death aktsia, during a selection – instead of going to a shmaltz grub [a pit of chicken fat, an indication of something good], I entered the camp itself. On the 2nd of April 1943, I and 300 Jewish men, women, and children were caught and arrested. Standing in a suffocating throng 90 in our cell, we barely made it through the night. On the 3rd of April 1943, very early, all 300 of the captured Jewish victims were led out of the three cells into the prison courtyard where the Gestapo Sturmführer [German paramilitary rank] Herman, may his name be erased, carried out a selection.

“Who should live and who should die” was only dependent on the direction of his finger. The consequence was that 200 men, women, and children were instantly taken away to the cemetery, and the remaining 89 men were loaded on two open trucks to Kamionka.

The work there consisted of breaking stones, pouring tar, digging, repairing, and keeping constant the material stream that led from Tarnopol to Kiev through Podwo³oczyska for military purposes.

[Page 371]

Nearing the area of the Kamionka camp, we met a group of exhausted people, half barefooted, their feet bloody, wounded, and swollen; their clothing was torn, dragging themselves with tired steps – in rows and singing (!). Their expressions were miserable and resigned, with frozen noses and ears. With empty bread sacks and thin mess kits hanging, they walked as if at a funeral to their camp grave and were ordered to sing a song with the last strength of their almost exhaled souls.

This was the first image, the first greeting of our coming days.

Arriving before the camp gate, soaked by the rain, we were ordered to place everything we had with us on a pile; thus each of us remained penniless. To my good fortune, Yosek Majblum, who was the camp doctor, saw me there. He covered his face in pain wanting. He asked, “How did you come here?” At that time, I did not yet understand how painful his question was. However, he immediately consoled and assured me he would help me if he could. At the time and in those conditions, such a promise was a rarity.

The camp was located near the main street 10 miles [16 kilometers] from Podwo³oczyska [Pidvolochysk]. It was very high uphill, and we had to bring buckets of water from the wells in the valley. Therefore, there always was a lack of water in the camp. The camp consisted of a long chain of horse and cattle stalls in a former Polish farmyard. In addition to the camp managing committee, the number of prisoners was always 700 people (men).

In order to explain to us immediately what kind of area we were located in, and how we had to act, they took our clothes from us to “delouse.” While we were standing completely naked, as guests, we were honored with 25 lashes, but if any of us fainted from the pain, pails of water were ready for the “lazybones” to revive them in order to finish with the other 25 concentration camp inmates. Cleaned clothing was distributed as was appropriate for a collective, a shirt, a pair of pants, and a jacket for every man. Yours, not yours; there was no mine or yours in a camp.

Beaten physically and troubled spiritually, we were taken to our apartments of clay-covered cattle stalls, with small windows and wooden bunks arranged one on top of the other. Everything was smeared with tar, a kind of strong tar that killed all sorts of insects. No linen and no covers; under the head - a slanting, suitable little board. This was prepared for 60 of our group. This was our residence, our place of rest.

[Page 372]

Everyone slept in their clothing because there was no heat, and we were not permitted to use any light because of the danger of fire. We lived under these conditions and, as previously mentioned, there was a lack of water. But we immediately received the club for dirty ears or, God forbid, for a louse. And this actually happened very often.

This is my account of the first day in the Kamionka camp. On the first day, after the welcome, in taking over the dwellings, we were considered as regular residents, and the internal camp management, which consisted of only “our Jewish brothers,” ruled over us. They were harnessed to the brutal work of more quickly reaching the “final solution,” to be free of Jews, with another spoon of soup or another potato, and with the false assurances that we would remain alive.

In my time there, the management of the camp belonged to “Kalts” – the commandant, a Jew from Germany who had escaped to Poland to save himself.

Cukerman – the vice commandant, an academic from Tarnopol.

Ellowicz – the barracks commandant, a refugee from Radom.

Kranc – police commandant, also a German refugee. <

Rotman – the council writer [secretary?], a refugee from Western Galicia.

A chief cook and an undercook to run the kitchen.

Twenty brigades to urge on the workers.

Twenty-five militia men, simply bloodsuckers.

As well as an overseer of provisions, a manager of the workshop division, a doctor, and a clinician.

They all devotedly carried out all of the orders from the Gestapo, believing the promise that they would be protected. However, the Germans, with their feeling of justice, treated “all Jews equally” and also paid them the same “death wages” as the ghetto Jews and as the Judenrat [Jewish Council]. The second day in the camp began paskudna [nasty] very early for the freshly arrived under the new leadership. At four in the morning, they shaved our hair off our heads. Everyone received a yellow Magen David [Shield – Star – of David] on the front and shoulder of their jackets. Everyone received a bread bag, a mess kit, and a spoon. Then a little bit of black coffee was passed out from the kitchen. At six o'clock, we stood with all of the other camp inmates, 700 in number, and waited for the Gestapo chief.

A tall German arrived wearing a long, leather coat with a riding whip (of the same color leather); he listened to the report, looked over the horde of slaves, and commanded:

March to work singing!!!

[Page 373]

After a walk of seven to 10 kilometers [a little over four to a little over six miles], we arrived at the workplace – everyone received tools, someone a pickax, a spade, a hammer to break stones, or a wheelbarrow. Every brigade of 10 men also received a designated order, how much and where to work that day.

Tormented for eight hours with deadly sweat, having absorbed a number [of blows] from rubber sticks from the brigadier, we crawled home singing. We had to stand in rows in the camp for a long time to receive the daily food distribution that consisted of one liter [about one quart] of soup (in which one had to search with a candle to find a diced vegetable), 20 grams of bread [about three-quarters of an ounce] (always moldy) and 10 grams of butter or 40 grams [about one and half ounces] of marmalade.

Thus, it was repeated day after day. This was what the daily life of the Jewish prisoner looked like. If he did not appear at the roll call because of a certain illness, he was healed immediately with a bullet. Two prisoners were specially designated as the khevre kadishe [burial society] specialized in the burial of the worthless [meant ironically] element. Standing in reverence, they carried out the “worthless one” so that everyone could see. The bundle of bones was laid down in the wood cabinet, covered with several shovels of dirt, and done. From December 1941 to May 1943, approximately 9,000 “parasites” were disposed of under the wood cabinet, I was secretly told by the writer Rotman.

We did not officially receive any mail, newspapers, or other information about what was happening in the world. We would ourselves learn [what was happening] according to the military traffic on the street or from secrets grabbed from the air. As a supplement to the picture of daily, normal camp life, extraordinary events occurred that remain deeply engraved in my memory, and I will tell about several of them.

by Moshe Bar David

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

They were together in a camp for an entire year. Suddenly, the son escaped. Because of this, the father had to endure a real hell. A reduction in food, heavy labor, whippings at every opportunity, slept not on a plank bed but in the passageway where everyone had to step over him in order to go by. Several days later, a Ukrainian policeman brought the son back to the camp with his hands in chains. We prepared for a terrible scene … “for our benefit.”

[Page 374]

As in all other camps, a gallows (a tall pole from which a rope hung down from an iron scaffold) was erected in the middle of the courtyard of our [camp] as a means of terror for bad behavior. There was no doubt that we would be witnesses to a frightening ceremony. In the morning, we all stood for rollcall, deadly pale in terrible trouble. The shackled “criminal” (Frajzinger was his name) stood under the gallows and waited for the “Angel of Death.” He [the “Angel”] came closer with a sarcastic smile, raised his head toward the rope, made a motion with his leather fajtshe (whip) pointing to the gallows, and ordered us to shout “Hoorah” during the ceremony!!!

At the last moment, the shackled one fell to the feet of the man from the Gestapo and asked him to change the sentence because of his father… An unbelievable miracle occurred!… “Give him 25 lashes,” the murderer ordered. All of us felt as if we had become frozen, but only for a short time. The young soul, exhausted, from fear and suffering, died at the 18th lashing. The emblem chai [life] had no effect, and the call to God did not help.

Two Brothers in the Camp

Only two young brothers from the murdered Halperin family of Trembowla [now Terebovla, Ukraine] remained alive. One was caught immediately and taken to the Kamionki camp, where he was lucky to become the bootblack in the cleaning stable of the Gestapo Hauptsturmführer [paramilitary rank equivalent to captain]. The other brother remained alone* …lucky to become the bootblack in the cleaning stable of the Judenrat [Jewish council] in Trembowla, they should help him to be with his brother in the camp. During a lapanke [akstie – usually a deportation], he was taken into a group of slaves in the camp militia. He actually wore the hangman uniform with a rubber club, but he was given guard duty. Every morning before the roll call, he would stand at the door of the barracks, where Jewish believers had sneaked in to grab a holy blessing and he would protect them so that, God forbid, there would be no evil eye because every gathering of even three people would threaten death.

*[Translator's note: there is a typographical error in the text. Text is repeated and/or missing. The text has been translated as it appears, including the errors.]

His brother, the boot-polisher would sneak in when the murderer was not in the house – to the radio - and would often bring news to us in the camp, which we would always interpret as being good. This strengthened us and helped us persevere.

Four weeks before the total liquidation (by shooting) of the camp, I really succeeded in getting help from Dr. Yosef Majblum to escape from the camp. Understand, it was through a daring plan and through unbelievable miracles. (But this is a chapter in itself.)

[Page 375]

How fortunate I was when after the liberation, being in Czortków [Chortkiv] as a bookkeeper while delivering the balance of my work, I met the two Halperin brothers. We all cried together with joy. And they told me the end of the Kamionki affair. The boot polisher overheard the noise and conversation of the drunk members of the Gestapo and immediately ran to the camp and shouted that the end was sealed for that night… Only approximately 100 men were able and dared to storm the armed camp guards and escape to the surrounding forests. They assured me that both of my brothers-in-law, Shlomo Zauberberg and Itshe Gros and his son, Pesakh, were among those who escaped. I was excited and hoped, perhaps… but all or almost all of those who escaped fell as victims of the wild forest epidemic that reigned in the forest at that time.

Those remaining in the camp were all shot the same night.

Passover in the Camp – 1943

Berezhany's wagon driver with the name, Rajbsztajn, would always bring bricks from brickyards to the houses being built; his son-in-law and Pinya Mehler's son, both prisoners from a year earlier, worked at the Av Barukh group. They would go to Jewish houses as well as those that were bombed and burned in the surrounding cities and villages and take the materials away for military purposes.

We already lay tired on the plank beds; a desolate night like all of our nights (no “why is this night different” [reference to the Four Questions asked on Passover]). They suddenly came into our barracks with matzos in their hands. They had probably found a living Jewish family somewhere near their work.

They crumbled the matzos into small pieces and distributed a piece to each of us. Agitated, with a wild voice, he shouted: Let us ask the Master of the Universe our questions?!…

A hearty moan and cry broke out. The feelings and thoughts of everyone passed like a hurricane, a whirlwind without control. The Haggadah was pouring out our bitter hearts without words – our tears and death sweat which ran like wine, the matzo was the substance and symbol of an exodus from the camp!

Our hope then for [the Exodus] were the bitter herbs!!!

[Page 376]

The Provision of Clothing in Camp Kamionka

Right after Passover 1943, an auto with used clothing, pants, jackets, dresses, underwear, long fur-lined coats, talisim [prayer shawls], and various children's garments came to the camp. Everything was dirty, wrinkled, and useful only as rags. These were the remnants from the cleaned-out Jewish homes. According to their method, they would always carry out a murder aktsia [action, usually a deportation] during a Jewish holiday. The Jews were taken to the crematoria, or later, when they lost their shame, [the Germans] murdered them daily at the local cemetery. And then they sold the most valuable things to the German families for small change; the less valuable household items were sold to the Volksdeutchen [ethnic Germans] by weight (50 kilos [110 pounds] for 2 zlotes] and the real rags were brought to the camp for the half-naked and half-dead camp Jews.

The rags had to be deloused before the division. Until the disinfection, the entire pile was thrown up in the attic of the supply barracks and the ladders were taken away so that, God forbid, no one should climb up and steal a bit of treasure, but the prisoners, with torn fringes on their half-naked bodies, made a living ladder, climbed one on another's shoulders and laughed at the “thou shalt not steal!” What was stolen [from the attic] was taken from many as well as the provisions for an entire week as a punishment.

This is just a minimal picture of camp life and the various abandoned legends of which the world, in general, was not informed, but hundreds of thousands of Jews suffered inhumanely and actually were tortured until a bullet freed them. These camp Jews drank up the bitter cup of Nazi poison to the very bottom.

It is hard to believe that a human life could endure this. As is evident, human suffering brings out inhuman strength!

May both remain for the ages! The one who reminds us and the one who remembers, of blessed memory!

by Moshe Bar David

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

|

There was a shtetl [town], clean and neat Near the golden linden, Life exterminated – ruins remaining Memories that demand – an echo that shouts.

White birch trees encircle

Meadows and fields turned green

Moonlit night – winter cold

Water cans draw crystal water

Street of Jewish houses – brick

Young people longing, dreaming of the future,

Window eyes look blue

Remained alone, but not unfamiliar

No headstone, no coffin |

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Berezhany, Ukraine

Berezhany, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2024 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 21 Apr 2024 by LA