|

Ozarow, July 26

|

|

[Page 95]

[Page 96]

Shime-Leib, the oldest son of a family of lime dealers on Ostrowiec Street, brought prosperity to the family business. In order to diversify, he also expanded into wheat. In time, he sat on a tidy fortune, due to his business dealings, but it was said, due also to his miserliness.

In summer, he wore only one suit, and in winter, his “kurtka”, a furlined three-quarter coat, seemed to be glued to his shoulders. Unlike people of his generation, who were all more or less sympathizers of some political movement, he had absolutely no interest in current affairs. And as for friends? “They all lead you astray!” he would pronounce. What about girlfriends, then? “Only good for squeezing money out of you!” he would smugly reply. In short, he was thick and coarse in every respect, fat, and with his flat and suspicious stare, constantly giving passersby the look-over. His only pleasure consisted of going to Shiffman's Inn on Saturday afternoons. Once there, screwed into his chair, he would watch the others drink, never buying a drop for himself. Instead, he would spend hours munching on the pumpkin seeds which filled the deep pockets of his indestructible kurtka.

At 24 Kolejowa Street was the beginning of Dumenyk's alley which entered the little road leading to the train station at Jasice. There, a family preparing to emigrate to Canada lived.

Their son Pinye was, however, stuck in Ozarow because he still had to do his military service.

On his return from the army, Pinye got married, and before you knew it, he was the father of a baby boy. Pinye's parents moved heaven and earth so that the young family could join them on the other side of the Atlantic. But the cost was just too great. Pinye had to leave for Canada alone, and as soon as he could, he would send the funds needed for the rest of the family to join him there.

Days, weeks and months passed .....but no news! One day Pinye's wife received a registered letter. Her heart pounded wildly. She thought she could already see Canada's shores on the horizon. But alas! — the words danced before her eyes — Pinye was asking for a divorce! Had her fickle husband fallen for another woman? Or had he simply come to realize that he no longer missed his wife and son? No matter why, she and her little Motele were now abandoned and penniless.

Soon a rush of communal solidarity enveloped these two unfortunates: “We must help this young woman overcome this difficult pass! So

[Page 97]

why not arrange a little marriage between her and Shime-Leib? Sure, he's stingy and cantankerous....but even he has a heart like everyone else. If she were kind to him, maybe he would change.” In the end, the scheme worked so well that the marriage took place.

Shime-Leib, known to be stern and not very sentimental, adopted little Motele and from the very start, treated him as his own son.

Years passed without any slackening of this paternal love. Shime- Leib, the egoist with a flinty heart, had come to know the pleasure of sharing. Never again would he be seen chewing his pumpkin seeds all by himself. No, on Saturday afternoons, comfortably settled at the corner of Kolejowa and Ostrowieca, Shime-Leib and Motele could be observed munching away together like two sly conspiratorial squirrels. Then came the war, the German occupation and the dark days of the black market. At the same corner Shime-leib could be seen, anxiously asking anyone who passed if they had anything to buy or sell.

One day in September 1939, a Jew stopped in front of him and offered to sell him a gold fountain pen. “My brother-in-law gave it to me as a gift in France,” the stranger said. “I had wanted to keep it as a present for my oldest daughter's fiancé. But what do you want ? We're in a war and my children are so hungry....

” Shime-Leib paid a tidy sum and bought the pen. He pocketed it and ran off to the corner of a corridor to see if it had a hallmark.

He was delighted at his purchase, but he couldn't figure out how the pen worked. “No matter!” he exclaimed. “My little boy will grow up and he will know how to use it! Surely not to write to his father, disappeared in some far-off country, but to me, in thanks for the love I replaced...”

It sometimes happened that children would lose both parents.

Shloime and his brother Moishe-Louzer found themselves in this predicament during their adolescence. Fortunately, their strong fraternal bond enabled them to deal with their plight. One day, Shloime, the older of the two married, but he still continued to take care of Moishe. At that time, a prominent member of the community, Itche Weinberg, and his wife ran a prosperous business in Ozarow. This childless couple took in young Moishe-Louzer, and they showered him with as much love and attention as real parents.

So it was that Moishe-Louzer, despite being an orphan, grew up in a warm household. And when the day came that he married a girl from a good family, Reb Itche and his wife had given him their unqualified consent. Two children issued from this union, and they became both a source of joy for the young couple and supreme recompense for Moishe- Louzer's aged adoptive parents.

The union of Meyer Cukier and his wife Yocheved did not seem to have been blessed by God, for the couple remained hopelessly infertile. But the wife had a brother in Stanislawow with a family as numerous as it was poor. One day Meyer and Yocheved went to Stanislawow and brought back little Yoissef, one of Yocheved's nephews. From then on, they raised him as if he were their own son and placed all their hopes on him.

The passing years filled them with joy, for Yoissef grew up without ever going astray. Everyone in Ozarow liked him immensely, and gave him the nickname Yoissef the Redhead because of his flaming red hair. His fellow pupils in the Talmudic school also respected him because of his brilliance. Before long he became engaged to Sylvia, the daughter of a ritual slaughterer from Drildge. She immediately received an invitation to come to Ozarow in order to be introduced to her fiancé's family. A few days later, the couple left for Stanislawow in order to meet Yoissef's natural parents. A Jewish coachman came to pick them up to drive them to the Jasice train station. They crossed the market place and everyone leaned out of their windows to look admiringly at the beautiful Sylvia and her Yoissef the Redhead.

As the marriage approached, Yocheved and Meyer Cukier decided to put their house in Yoissef's name. The building served them as a grocery, as well as their dwelling.

[Page 99]

“No gift is too beautiful for him !” they thought.

The house was temporarily separated in two, as was the shop. In that way, the young couple were able to preserve both their intimacy and their independence.

Unfortunately, Yocheved died the next year, and her passing profoundly affected Yoissef who had benefited so much from her love and tenderness. The pain was all the greater because given that his natural parents were still alive, he could not even say Kaddish over her grave.

In 1942, when I arrived at the labour camp, I noticed Yoissef at the registration office. From that moment, we never saw each other again. Later, I learned that he had been included in the first selection.

One day, I received word from Sylvia who asked me for news of her husband, since for a long time she had had no sign of life from him. I lacked the courage to answer her. Instead, I wrote to my mother to let her know that our dear neighbour Yoissef the Redhead was no longer among us.

Yisruel-Itzchak Rozentzveig

My brother was born on October 20, my sister on December 15, and myself on July 25 — the year of our birth date is less significant — but for sure, we weren't triplets. Each of us was definitely born in Ozarow, but in a different year and on a different month and day, and it was old Yisruel-Itzchak Rosentzveig's job to declare us to the governmental authorities.

It was in fact he who was responsible for relations between the Jewish community and the public administration. At that time, that kind of relationship didn't come easily. First of all, it was necessary to adequately master the Polish language, and secondly, as soon as anyone entered a government office of any kind, they found themselves standing in front of the white eagle — the national symbol — and a crucifix hanging on the wall. Experiences any Jew would find humiliating.

So, whenever a child was born, his parents informed Yisruel-Itzchak — a man who could neither read nor write, yet possessed a prodigious memory. First of all, he would mentally engrave the first name or names of the newborn. Then, in order not to forget the date of arrival in this world, he would fold a corner of a page of his haftorah (prayer book containing the Torah portions). Thus, he might remember that the baby had first seen the light of day during the week of Chanukah, the 15th day after Passover, or maybe on Tishe-ba'Av, when Jews mourn the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem.

He didn't bother registering one child at a time, but he would accumulate a consecutive number of dog-eared pages of his haftorah. Only then, would he attend to the task. Meanwhile, other children would be born, sometimes within the same families. There was a legal obligation to declare the birth of a child, but not necessarily on the very day of his birth. Thus, Yisruel-Itzchak would always recommend reporting the date of birth of a boy as late as possible: “That way, they would have more time before they had to appear before the draft board! Maybe even to get married before then, and give you grandchildren. That would always count for a little more time gained!” he would say to the family of the newborn.

On the other hand, he prescribed the opposite approach for girls: “It's necessary to declare them at once; if not, in only a few years from

[Page 101]

now — and God knows, they go by quickly — you'll have the unpleasant impression that you have to marry off an old maid!”

Given the way Yisruel-Itzchak went about his job, he ran the risk of making really funny mistakes. Thus, once he declared the birth of a boy to the authorities, confusing his birth with that of his sister, who was by then only ten years older! So, a few years later, a couple of policemen arrived at the door of the “young man's” house with orders to arrest him. But how could they take away a little ten-year-old boy playing innocently in the sand in the court yard? Just the same, the mayor obliged his parents to present themselves to the civil status authorities, accompanied by all their children. So they re-registered. The ages of the children were simply estimated, so that no child from that family would ever be able to confidently affirm: “I was born on such and such a day in such and such a year!” This lack of precision was highly prejudicial to those who applied for emigration. Most of them had to confront inextricable difficulties because of an incorrect entry in the registers of civil status. In that time, boys could no longer obtain passports after age eighteen, but had to wait until age 21 or 22 so that they could first come before the draft board. Thus, for many the question of their civil status had very serious consequences.

|

|

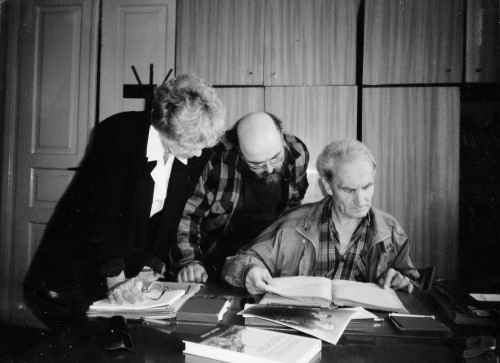

| Gloria Tannenbaum reading birth registration of her father Max Shaffer Ozarow, July 26 |

[Page 102]

Chaim-Meyer the Beadle and Cemetery-keeper

The Jewish community of Ozarow owned its own cemetery, and administered it, allocating graves as the need arose, without plans or records showing whether the plots were free or already occupied.

Chaim-Meyer Goldblum, who was the beadle and the right-hand man of Rabbi Chaskiel Taub, was also in charge of the cemetery. It was said of him that when the time came for him to appear before the draft board, he preferred to put out one of his eyes rather than serve in the Czar's army — with the result that he retained a strange staring look which frightened all the children.

Today we would say of him that he kept a computer tucked in a corner of his brain! For indeed, he retained the plan of the cemetery in his head, down to its smallest details. He knew which plots were free or occupied, as well as the identities of those whose gravestones did not yet have any inscription. His prodigious memory allowed him to store the names of all the deceased, as well as the dates of their deaths.

Whenever people from out of town wanted to gather at the graves of their family members, he would infallibly lead them to the correct location, even if the inscription on the grave stone had long since been worn away with the passage of time.

Every day he would make the rounds of the village, down to the smallest back street, in order to remind people of the death anniversary of their loved ones so that they would not forget to recite the Kaddish. And if the reminder was intended for a non-observant son or a childless widow, it was Reb-Chaim Meyer who took it upon himself to recite the memorial prayer in their place.

Whenever you left the village centre, heading northwest, you would come to Spacerowa Street — the Esplanade — which led in one direction to the synagogue square, and in the other to the market place. There on the fringe of the ritual slaughterers' neighbourhood, lived Ozarowers who formed part of a large clan. Their names? Weinryb, Cukierman, Goldblum, Mandel, Melman and many others. But everyone in Ozarow lumped them together under the nickname, the “Spivoks”.

This sobriquet had nothing to do with any physical trait, as typified by the parade of “Redheads”, “Brunettes”, “Gimps”, “Hunchbacks”, “Fatties” and “Skinnies” — nor with any profession. No! “Spivok” was a derivation of the Polish word “spiewak”, or “singer”. How did this nickname originate? All of these families attended services in Rabbi Chaskiel Taub's “shtieb'l”, or prayer house, and were followers of the great Rabbi of Modjec, who was the most popular chassidic cantor in all of Poland. And what else could a follower of such a personage do but sing? Or perhaps dream of spending the holy days in his company. And when this dream came true, he would return to his neighbourhood in Ozarow with a repertoire of new hymns to sing and stories to tell for the rest of his days.

Moishele Rivke's, who lived on a corner of Spacerwowa Street, was the dean of the “Spivoks”, respected by all. His large house of several stories teemed with his children and grandchildren, exuding gaiety. Everyone in this little world respected a well-established Spivok tradition: intermarriage within the group. Thus, for example, Chaskiel Weinryb married his cousin Mala, the daughter of Yankiel Weinryb. As for Chaskiel's sister, she wed Yankele, the son of Shloime-Isaac Cukierman and the older brother of Max Cukierman. Respect for this custom enabled the “Spivoks” to maintain their cohesion and to team up in order to carry on certain businesses together.

Walking down Spacerowa Street, you would pass several other “Spivok” houses, belonging to Hertzke Weinryb, Yankele Meilech's (Weinryb), Yerm'ye the Scrap Dealer, Leibish-Meyer the Tailor, Moishe the Locksmith, Moishe-David Rosentzveig the Synagogue Beadle, Abraham Paluck (Mandel) and Chaim-Meyer Goldblum, whose two sons — Chil and Itzchak — married two sisters of Shyale Kleinmintz — Gitche and Perele.

[Page 104]

The first of these couples emigrated to France, while the second remained in Ozarow in the house they inherited from their parents and grandparents. Two other children of Chaim-Meyer Goldblum, Bairish, and Chaya-D'voira, who married Avrum-Itzik, settled in France.

All of the Spivoks, with the exception of Shloime Isaac Cukierman and Moishe Weinryb, lived near each other, making their living from business. Some kept grocery stores, but most, like the Weinrybs, sold wheat. And the children took after their parents. Not one broke custom by learning a manual trade.

Leibke and Moishe-Chaim

Beside Number 3 Ostrowiecka Street, you would come across a house with a narrow front and a glazed front door to enter the store on the ground floor. From there you could go up to the first floor where Moishe-Chaim Hochbaum's family lived. A small courtyard led into the lane where you could find Shulim the Butcher. In the store Moishe- Chaim sold beer, as well as various other forms of liquid refreshment, including the lemonade made in Ozarow by the partnership of Cheynoch Kleinmintz and Shaul Daches.

Number 5 Ostrowieca Street belonged to Alta Youme's. While her husband Youme was still alive, the “Spiliters” (inter-city wagon drivers) would regularly stop at their place to spend the night in a decent bed and get a good meal. Youme's grandson, Yoissef with the Twisted Mouth, once showed me his grandfather's hand-lettered sign in Hebrew, which read “MACHULIM TOVIM V'MACHOM LELAIM” — good food and lodging. After Youme died, everything changed. Their shop was divided in two. In one half Leibke, Youme's son, sold sweets and drinks, and in the other, Alta just sold tea to the customers. Often while on her way to the table, she would take a couple of good swigs from the glass. If the irate customer then asked, “How come you're drinking my tea?” she would answer, “I'm just tasting it to make sure it's not too hot and that it's sweet enough!”

Between his neighbour at Number 5, Leibke Youme's, and the one living at Number 3, lived Moishe-Chaim Hochbaum, who sold beer, and was a member of Moishe-Yoske's family. Relations were far from neighbourly. This was due to intense business competition, as well as Leibke's irascible character, contrasting with Moishe-Chaim's mild temperament. Leibke would dump his garbage on the side of Moishe-Chaim, who was then obliged to get rid of it. It's all right to be even-tempered, but surely there are limits!

On Kol Nidre evening of 1938, a fight broke out between them. Physically, Leibke had the advantage, but the incident came to be recalled as the Moishe-Yoske's Affair. Someone alerted Shyale Rohme's (Kleinmintz) who quickly arrived at the scene, accompanied by his two strapping sons, Cheynoch and Leibish.

[Page 106]

They were joined by Shimshon Grohman's three sons and Hersh- Yoissef Kleinmintz, who had run all the way from the Tarlow road, in the northern section, and across the market place, rounding up all the members of the Moishe-Yoske's family they could find on the way.

I tagged along. When I got to the scene, I saw my Aunt Malka already engaged in defending Moishe-Chaim Hochbaum with her formidable arsenal of curses. This time Leibke didn't emerge the victor. Humiliated, he retreated to his house and sent his wife outside to close up the big doors to his shop.

Laibel the Limper and Simcha

Moishe-Chaim Hochbaum's brother, Laibel “Koulos”, or the Limper, emigrated to Canada around 1910. Ozarowers were fond of telling many stories about him, especially about how he knew how to win the respect of Catholics, as well as Jews. One of his best friends was Simcha Mosh'ke's, the best hairdresser in town, but a man who preferred to let others work if he could help it. Honesty was certainly not his strong suit.

After the First World War, Laibel the Limper invited his friend Simcha to come to live in Canada, but warned him that there he would have to live like an honest man. Simcha, however, would have none of this. And Laibel, who had guaranteed his friend's good conduct, was forced to make him leave Canada.

In 1934 Laibel came back to Ozarow to see his father, brother, sisters and friends once more. Anyone who had a relative living in Canada came out to pay him their respects, for in Canada he was an important man — the president of the Ozarowers' Benevolent Society. They opened their hearts to him as if he were a visiting grand rabbi. He listened attentively to all their sad stories and made promises to help. Promises which he would surely keep. Twice a year thereafter, at Rosh Hashonah and at Passover, he would send money from Canada to his father Hershel Hochbaum, who would then make the distribution. This went on right until the outbreak of the war.

The oldest daughter of Moishe-Chaim, whose name, Perele, was — strangely — the same as her younger sister's, had long been of marriageable age, but seemed to have scant chance of finding a suitable boy. Yet, with the visit of her Uncle Laibel from Canada, everything changed.

Now, all the marriage brokers came knocking on the family door with offers of introduction to young bachelors. The mere promise of

[Page 107]

Uncle Laibel to sponsor their emigration to Canada had made Perele a very desirable catch indeed. Zelig, the son of Idel the Baker, had the good luck to be approved by Uncle Laibel, and the marriage was quickly arranged so that the eminent uncle from Canada could attend before returning home.

On the eve of the wedding, Simcha Mosh'ke's went to pay a call on his old friend Laibel Koulos. They fondly reminisced over that wonderful time when one market day in Ozarow they had, with their boots on, danced a fine dance on crates of eggs, making a giant omelette which spread over the paving stones of the marketplace.

“Yes, I remember all of that well,” said Simcha ominously,”but the real reason for my visit is to find out why you got me thrown out of Canada!”

“You are still my friend,” replied Laibel placatingly. “It was all an unfortunate misunderstanding. In fact, I've come here to set things right by bringing you back with me. Tomorrow there's a wedding at my brother's. Come to see me afterwards and we'll settle the whole thing.” Laibel knew that his life was in danger. Simcha had certainly not come to visit with the intention of forgiving him. So he decided to discreetly take his leave of Ozarow, and as fast as possible. The wedding took place as planned, and for Laibel it was an occasion to bid farewell to his old father Hershel and his brother Moishe-Chaim. As the guests were leaving the party, Laibel went out the front door disguised as a woman, with a wig, and a pearl necklace around his neck. In a tiny back alley, a taxi, brought in specially from Ostrowiec, waited to take him to Warsaw and safety. Farewell, farewell, Simcha-Mosh'ke's...

Henri Kaplan

The oldest son from the first marriage of Moishe-Chaim Hochbaum was called Henri Kaplan, but Kaplan was not an Ozarow name. It was said that at the beginning of the century Moishe-Chaim had married a woman from Solec, about forty kilometres away. As was the custom, they were married at the rabbi's, and a child was born of their union whom they named Aarele.

Soon after, they divorced, again at the rabbi's. The young woman went back to her home town, where she registered the baby boy under her maiden name, Kaplan. As an adolescent, Henri Kaplan came back to

[Page 108]

Ozarow to live with his father, and the two emigrated to France around 1925.

Malach, Adler or Hochbaum

Kive Malach Adler, also a member of the Moishe-Yoske's family, was born in 1908. While his parents, who had married at the rabbi's, had registered the marriage at the town hall, they neglected to register the birth of their little boy, Kive. Shortly afterwards, Shloime, his father, left for America, and one day, his mother Malka received a certificate of divorce in the mail.

Later, she married another Shloime — Shloime Karp — with whom she had four daughters: Esther, Kreindel, Feiga and D'voira. When Kive reached adolescence, his father from America asked him to come and live with him there. His mother Black Malka said, “No, my only son will not go to live with a father who abandoned us.” She registered Kive at the town hall under the name Malach. Why Malach? If she gave the real name of his father, Adler, sooner or later he would be taken to America. If she gave him her maiden name Hochbaum, it would also be easy for the father to trace her only son. On the other hand, the name Malach was unknown in our milieu, and also reminded us of Malach, the angel who died young and childless.

Kive left Ozarow for Lodz, one of Poland's biggest cities, where he worked as a tailor. He arrived in Paris in the 1930's. Since his papers weren't in order, he left in 1937 for England where he spent the war. In 1950 he went to Canada and the United States in order to meet the family, both on his mother's side and on his father's, since it had been a marriage between cousins (Hochbaums and Adlers). In Detroit Cousin Harry told Kive that his father Shloime hoped to meet him. After forty years of heartbreak, the father Shloime Adler met his son Kive Malach, who under Cousin Harry's influence again took up his real name, Kive Adler.

Visiting his friend Chaim Sherman in his factory in Brussels, Shya Tenenbaum picked up the story which follows. In it, Chaim Sherman traces the history of his family, whose central figure is his great-grandfather from Ozarow, Reb Yoiel Fudym. This chronicle, replete with love, hate, heartbreak and reconciliation, in its fashion, throws light on an era tragically gone by.

It was in 1860.

Reb Yoiel Fudym was working as a tailor — a trade which had been a family tradition for several generations. According to legend, one of his grandfathers could even boast of having worked for the royal court of Jan Sobieski, the last king of Poland, from 1673 to 1696. It was noted that His Majesty, his ministers and his generals were not a little proud of the patriotic attachment vouchedsafe to them by their Jewish tailor.

A worthy heir to his forefathers, Yoiel Fudym was an expert professional. He did work for the great landlords, making them their “sukmanes” — traditional overcoats, fur garments and “tchapkas”, or fur hats.

A large number of working class Jews participated in the 1863 insurrection which sought to overthrow the Czar. Reb Yoiel attended clandestine meetings of the committee of village notables. His incessant patriotic activity soon earned him the admiration of certain Polish aristocrats. At the same time, he had frequent entrée to the sumptuous manor houses of the landlords in order to do fittings and to deliver finished garments. Still, he knew the Talmud well, for his parents had not neglected to give him a solid religious education. Furthermore, he spoke excellent Polish and Russian. He knew, when the occasion required, how to sing a revolutionary anthem or recite the quatrains the poets wrote to denounce the Czar and exhort the people to rise up.

But in time, the Czarist police invaded his workshop and arrested him. They interrogated him brutally, pumping him for information without let-up. Why was it that Reb Yoiel and his fellow workers toiled so devotedly day and night? They made him strip and battered him black and blue with their blows. Reb Yoiel was then thirty years old — very robust and endowed with unusual moral courage, which enabled him to resist this harsh treatment without denouncing anyone. He was finally brought to trial and sentenced to ten years of hard labour in a Siberian penal colony.

[Page 110]

So there was Reb Yoiel in the prime of his youth, forced to leave his wife and ten children and all his friends. Fortunately, all of his wealthy customers didn't forget him. The landlords from the surroundings saw to it that the Fudym family would not want — for meat, flour, milk, cheese or moral support. And for ten interminable years Reb Yoiel fought isolation, the freezing climate, hunger and illness. Yet, his moral and spiritual energy remained intact, as did his faith. Even in Siberia, he continued faithfully to observe the religion of his ancestors. He even found time to study Torah in the company of a few other Jewish prisoners. Above all, he never lost hope of one day reuniting with his family.

The day came when he was set free. From his penal colony, he had to cross the immense Siberian wilderness. He carried with him the skins of two white bears he himself had killed and a little case containing the gold he had managed to earn from tailoring during his years of detention.

Finally, he made it to Ozarow. Imagine his joy at once again seeing his ten children, some of whom were already adults. But he also had to bear immense grief, for his beloved wife Feiga-Sheindel had died long before his return.

Little by little, life once again took its course. Reb Yoiel married off his oldest daughter to a fine boy from an honourable family from Kielce.

He was able to provide a beautiful dowry and the wedding was splendid.

A great procession filed through the streets of Ozarow, making its way to the synagogue to witness the ceremony. A couple of facetious guests decked themselves in the by now legendary bear skins from Siberia. In the evening the entire village was lit up by the flaming torches which bold horsemen, astride their pawing mounts, passed and repassed from hand to hand. All of Ozarow was in a state of jubilation.

Many years later, Libale, now a grandmother, still talked about her wedding to her wide-eyed grandchildren. She would relive that extraordinary day and her voice would tremble with emotion.

Little by little, Reb Yoiel became an influential person in the locality.

The important landlords continued to be friendly toward him, and he became a “Dozer” or counsellor to the organized Jewish community.

On Sabbath and on the holy days, he could be seen from afar in his chassidic garb, topped by the shtraim'l, the traditional hat of orthodox Jews. Presently, he came to own a carriage drawn by two fine bay horses. He had an impressive synagogue and ritual bath house built. Soon he

[Page 111]

also made a gift to the community of two lots. One, in the very centre of the village, would serve as a residence for the Ozarow rabbis. The other became a cemetery adjacent to Ozarow so that her dead would not have to be buried in other villages. Reb Yoiel enjoyed the esteem of everyone, and this was due to his great generosity.

He kept an open table at which several guests could regularly be found. He distributed subsidies to the rabbis to permit them to live more decently, and on certain grand occasions, he even brought in a cantor from Warsaw.

Nevertheless, he remained concerned, for the future of his children was a constant preoccupation. They needed a mother. That is why one day he married a woman called Sura-Ita, a widowed midwife. A little while later the youngest son of Reb Yoiel, Berele, married one of Sura- Ita's daughters.

From then on, Reb Yoiel seemed to have everything to assure him a serene and happy life: a large, united family, material affluence, universal respect and consideration, and a peace within his soul which gave him the certainty of living harmoniously with the precepts of the Eternal.

Alas, it must be written that he would never again know such felicity.

One night during Purim, Reb Yoiel had a long meeting with his son Berele whom we have just been talking about. Did he give way too much to the general jubilation which reigned? Could it have been that his mind was befogged by the good bottle of wine he had just merrily downed? All the same, it ended that Berele, his watchful son, seized the opportunity and convinced his father to make him his sole heir. You can imagine the bitterness and hatred which each passing day afterwards, tore away more and more at the family so recently united. And the melancholy old man became a tragic witness to the pettiness of his own children. One day in a fit of anger, one of his grandchildren, Meyer, the youngest son of his daughter Libale — grabbed an axe within easy reach and threatened his grandfather with it. He was only fourteen years old.

From then on Reb Yoiel lost his desire to live. He became anxious and morose with despair. Why go on if his own grandson could threaten to kill him like a savage beast?

One night he entered the room where it was his habit to pray and he opened the holy ark. A great peace came over him and it was in all simplicity that he was then able to confide his secret desire to the Master of

[Page 112]

the Universe: he was worn out and no longer took any pleasure in living. To die was the only thing to which he aspired.

Having uttered these words, he felt an immense weakness invade his body. He collapsed to the floor. His soul took flight. He was a little more than sixty years old.

His death plunged his family and all Ozarow into profound grief. An immense crowd accompanied his body to the grave. Even the great landlords insisted on paying him homage at his final resting place.

It seems that in the ensuing years his family and posterity were afflicted with a strange curse as if they had never been pardoned for pushing a man like Reb Yoiel to the last extreme.

Berele, to whom Reb Yoiel had left his entire fortune, was not a happy father. Contemplating Bruchale, his daughter, the unfortunate Berele would say to himself: “A skinny redhead! Honestly, how could anyone fall for such a creature? Maybe in an extreme case, someone could find her green eyes attractive, but it's too bad that she is so horribly cross-eyed.” Yet, wouldn't you know but Meyer, the son of Libale, the selfsame grandson who had sacrilegiously threatened his grandfather with the axe, fell passionately in love with his cousin Bruchale. Berele went into a mad rage. “There is no way that Meyer will ever marry my daughter. This criminal is responsible for the death of our father (may he rest in peace). May he be banished from our family! May he go rot in some far-off hole and fall prey to remorse. May he suffer for his sin until the day he dies.”

He stuck fiercely to his position and remained inflexible on the matter. So Bruchale didn't marry her cousin. Instead she ended up marrying Fishele Gewandsznaider, a part tailor, part pedlar, but it was not to be a happy union. In fact, their first child died at a tender age, the second was born blind and the third deaf-mute. One day while he was playing by the side of the road, the third child was crushed by a passing cart.

For a long time Meyer lived unhappy and ashamed to have been so rejected. He moved from Ozarow to Ostrowiec, thinking he could get a fresh start in life by marrying a girl who, while admittedly not brilliant, would be someone with whom he might find happiness. That is not the way it turned out. Disputes and quarrels arose between them with increasing frequency. Meyer could not settle for a divorce because his wife had given him children. One day his youngest daughter, little Sarah-

[Page 113]

Gittele, fell into a well and drowned. The curse had once again struck the descendants of Reb Yoiel.

According to tradition, the firstborn male of a Jewish family is named after one of his forefathers, and everyone then tries to discern some resemblance to the departed patriarch in the little boy. He may exhibit the same deep blue eyes, the keen intelligence or the promise of the same athletic build as the deceased. The memory of Reb Yoiel was cherished, but feared as well. In looking at Yoiel, Meyer's only son, you were struck by the incredible resemblance and you couldn't help but think that the grandfather had returned incarnate in the baby boy. He grew up to be a living reproach, silently demanding a settling of accounts for his father's sin committed so long ago.

In time Meyer's son, Yoiel, grew up to be a handsome young man.

One day while he was walking in the woods looking for mushrooms and blackberries, he ran into a band of Polish thugs. A violent scuffle broke out from which he managed to escape with great difficulty, dragging himself to his parents' house, where he collapsed on his bed and fell into a sleep from which he would never awake. The doctor, who had been urgently summoned, arrived only to pronounce the young man dead as a result, he said, of the blows which had left their marks on his body. The whole village followed his remains to the Ozarow cemetery, where he was buried beside his great-grandfather, Reb Yoiel.

Crushed by grief, his father Meyer would never return to Ozarow. Every Thursday he would fast in an attempt to expiate the sin of his boyhood. He neglected his appearance and his unkempt beard made him look like a wild animal, like one of those fierce bears that his grandfather had killed in the depths of cold Siberia. Like his grandfather before him, Meyer threw himself into the revolutionary movement.

More often than not, he would bear the red banner high at the head of parades of manifestation. In the midst of one of these manifestations, on May Day, he was violently attacked by the Czarist police. He succeeded in wresting away the sword of one of them and threatened him with it...just as long before, when he was fourteen, he had threatened his own grandfather with the axe. He was arrested, judged, convicted and imprisoned for several years in Ostrog. Meyer managed all the same to emerge alive from the Czarist prisons. Tortured and unrecognizable, he returned to his family when he was set free, but neither his wife nor his children wanted to have anything more to do with him.

[Page 114]

Broken morally and physically, he took to wandering aimlessly in the surrounding forests, until the day when hunters discovered him dead. Struck by Reb Yoiel's curse.

Laibele Fudym, nicknamed “Payes”, had gone against family tradition, by becoming a shoemaker, the best in the region. He cobbled shoes and boots for the Polish landlords, just as in bygone days Reb Yoiel had clothed the local aristocracy. He died young and his widow Brandel didn't survive him very long. So the rest of the family had to take in Yoiel and Hershel, the two young orphans they left behind. It was agreed that they would spend one day a week with each relative.

Sura-Ita, as Shya Tenenbaum recalled in his chronicle, had married a second time to Reb Yoiel. Even in our day, she continued to practice as a midwife, helping with the lying-in of young women, just as she had for their grandmothers and for some of them, even their great-grandmothers. She died at almost one hundred, only a few weeks before the outbreak of the war, as if she could sense the menace looming for the Jewish people and preferred to take her leave before the catastrophe.

Chaim Sherman, the Brussels tailor, one of the few descendants of Reb Yoiel, survived the Hitlerian nightmare. And it was one rainy day in autumn that he told his family's story to his friend Shya Tenenbaum, seated on a wooden stool near the sewing machne. While Chaim talked, his friend looked at the sheets of rain falling to earth. “You know Shya,” he said. “I'm leaving for Montreal. I'm invited to attend the wedding of a girl whom I used to cradle in my arms when she was a baby here in Brussels. Her entire family will be there to greet me and it will be a wonderful reunion.”

Soon after Chaim Sherman left for Canada, but once there, maybe exhausted from the trip or by overwhelming emotion, he took sick as he was leading the young bride to the wedding canopy. A few minutes later, he expired without ever regaining consciousness.

Thus he joined in death all those whom the curse of Reb Yoiel had struck before him.

(April 12, 1913 — September 25, 1996)

Eulogy for a Hero

Mechel Flicker was born in Ozarow on April 12, 1913. He was booked to sail to Quebec in June 1928 on the same ship as the translator's father, but two weeks before, the cousins who had sponsored his immigration, fearing that he would become a burden to them, withdrew their sponsorship, dooming him to remain in Ozarow until the German invasion. A skilled mechanic born into a family of wagoners, he expanded that tradition by operating two taxis with a couple of partners during the late 1930's (see page 80). He survived the Holocaust by heading for Russia, where he was arrested and sent to a labour camp in Siberia for two years. After his release, he wandered on foot through the former Soviet Union, supporting himself by doing odd manual jobs. At the end of the war, he elected not to return to Poland, where he had no one and nothing left. He was placed in a displaced persons camp in Germany, and from there finally emigrated to Montreal in 1947 — 19 years later than he had planned. He had a family and owned a small scrap metal business. He became a pillar of the Ozarow synagogue in Montreal, Congregation Anshei Ozeroff, and he was zealous in the perpetuation of the memory of the town. These are the words of love and tribute spoken by his son David at his funeral in Montreal on September 26, 1996.

I stand before you to speak of and to honour our father, Michael Flicker. I stand before you on behalf of myself, my sister Gail, and my wife Ruth, who was a daughter to him in every sense that truly matters.

How to encapsulate the life and spirit of a man in a few words? I cannot do so, but most of you who are here today knew him well — knew his strengths and weaknesses (the former far outweighing the latter) and the profoundness of his ability to love and to give of himself. My father needs no eulogization: his life speaks for itself and it speaks far more eloquently than I ever could.

Nonetheless, it is altogether proper and fitting to speak of our loved one, and so I will briefly do.

Michael Flicker was buffeted hard by the turbulent winds that blew over 20th century Jewry. He was born in Ozarow, a small Polish town. While he was still a baby, the town was razed as armies swept back and

[Page 116]

forth across south-eastern Poland; and my father's parents spent the next few years as refugees before they could return home to Ozarow after the war. Ozarow made my father what he was: he was begotten of and shaped by the life of the shtetl. By the mishpochah, by the cheder, by the marketplace, by the beis hamidrash, by all the richness and tempestuousness, by all the liebschaften and all the broiges that contributed to the ornate brocade that was Jewish life in Eastern Europe.

But my father also had a technical side. Time and circumstance denied him any formal education, but he was a master mechanic. Around my father, machines were simply happier and ran better. His work may not have been aesthetically pretty, but he always made things work. Much of his learning was self-taught and his technical skill innate, but part too was acquired when he served four years in the army as an engineering sapper, the most arduous of all services in the Polish army. My father never tired of telling his children and then his grandchildren of his exploits in the army. My father was a very “talentful” man.

And he was a survivor. He survived infancy in war-torn Europe; he survived poverty and want, often going hungry to cheder; he survived cancer in his later years; and he survived the greatest tragedy of them all. After a year of German occupation, a soldier told him that he must escape for the next day the Jews of the town would be slaughtered. My father ran to the town elders, but they refused to believe him — “Of course the Germans are bad, but they are not animals. Such a thing could never happen. Not here and certainly not now.” That was the last day that the Ozarow he knew existed. On the morrow, the SS moved in to perform their abominations. My father in his later years crafted a remembrance tree on the leaves of which he inscribed the names of every family member he lost that day and the days that followed. There are a 112 names on the leaves of that tree.

My father escaped the Germans, but his trials had just begun. He was quickly arrested by the Russians as — of course — a capitalist spy and sent as a prisoner to Siberia where he survived for two long years. All around him, people simply lost the will to live and succumbed. But my father did not. He survived! And why? Because he had an implacable thirst for life. On shabbos, when we would gather around the table my father would point to Ruthie, to me, my sister, and each of his grandchildren and say that this was why he had survived. This was why he had

[Page 117]

told himself every day that he must live just one day more. That he would rebuild the family life that had been torn from him. And he did!

During the war he met my mother in the far eastern Soviet Union and their's was a marriage of true love. My father was a man of strong will and perhaps had a highly idiosyncratic way of manifesting his love, but it was nonetheless unmistakable. He honoured my mother and she honoured him. And it was good. It was so good, in fact, that they were married three times . . . to each other. The first marriage was under a “chuppah kiddushah;” the second was a Russian civil marriage that, as my father delighted in recounting, cost a grand total of four kopeks; and the third by a US chaplain in a DP camp in Bad Reichenhal. My father got a lifetime of very good value for his four kopeks.

The years in Canada were good years. Somehow he had the moral strength to emerge from the blighted and blasted ruins of Europe and to rebuild a life. . . to take a small step and then one step more and then to stride. Think of the courage that he and his generation have displayed. There is something to this Yiddishkeit that enables our people to say “Mir zeinen do” no matter how terrible their travails.

Our home, though never rich, was always warm and loving. Our door always open. Our needs never unsatisfied. My father was protector and provider. He worked very hard: his days were long and his hours filled with toil. But there was somehow a sense of joy in his work — he was providing for his family and that was a source of great satisfaction to him.

But to give to one's own is not really tzadakeh. My father enthusiastically helped others. From the family members he brought to Canada, to the loans he signed for his friends, he gave wholeheartedly and unstintingly. And perhaps, most of all he gave back to Ozarow through his tireless devotion over nearly 50 years to his beloved Ozarower Shul, Anshei Ozeroff, of which he served as an officer for many years.

My father was not a saint nor was he a simple man. He needed to do things his way and it was not always easy for him to get along in institutions or in large groups. He was quick to learn and hard to teach, needing to understand intuitively rather than through instruction, but he cherished learning nevertheless.

I will conclude with a brief personal anecdote that goes a long way towards portraying the man my father was.

[Page 118]

Our son Paul was in grade 1 at JPPS, (Jewish People's and Peretz School), Sarah was entering nursery school and Charles was a newborn. Ruthie had just decided to cut back to working half-time. Child care expenses were high and I was not yet earning very much. We didn't know how we would make ends meet with all the expenses we were facing. On a Friday afternoon, my father, still sweaty and dirty in his work clothes, came to Ruthie. He took her hand and placed in it a fist full of money. The amount was far more than he and my mother could easily spare, but he said just four words: “Far der Yiddische Schule.” Then he smiled and walked quietly away.

|

|

| Mechel Flicker striking a jaunty pose on an Ozarow street in 1936 |

[Page 119]

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

| Top left: Perel Youkef's Kestenbaum, “the mother of the poor”, with her husband Leibel Top right: The Birenbaums, Ozarow 1930. Back, Raisel, Sarah & Marmish Front,Yocheved, Chaskiel & Yechiel Bottom left: Shya Kleinmintz, Reb Reuven Epstein's right hand man |

||||

[Page 120]

|

||||

| Zangvil Waxman, front centre, photographed with his colleagues in a Polish army shoe repair detail during the First World War |

||||

|

|

|||

| Left: Moishe-Mendel and Nesha Grynspanholc Right: Jacob "Yankev" Meyer and Marme-Rivka Fraiberg, grandparents of the translator |

||||

[Page 121]

|

||||

|

|

|||

| Aaron Moishe "Moe" Fraiberg and Sarah Fraiberg, father and aunt of the translator, as children of 11 and 8, and as teenagers. The picture of Moe, then 17, was taken a few months after his arrival in Montreal. | ||||

[Page 122]

|

|||

| Elye, Shya (Charles Rothman) and Berel Rochwerg, maternal great-uncle and uncles of the translator photographed in Montreal in 1921 or 1922 | |||

[Page 123]

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

| Top left: Yocheved Fraiberg (right) Top right: Joseph Weissfogel (right), father of Rosalie Wise Sharp of Toronto Bottom left: Moshke Manheim, hero of the Spanish Civil War Bottom right: Mechel Flicker on his motorcycle, circa 1936 |

||||

[Page 124]

|

||||

| Portrait of Shaul and Chayke Grynspanholc dated December 31, 1938, sent to their aunt and uncle Frayda and Zangwil Waxman, who had emigrated to Montreal in 1935. This young couple died at Treblinka less than four years later. | ||||

|

|

|||

| Left: Frayda Waxman, seated right, and Frayda Rochwerg, standing right centre, with some

young cousins. Right: Frayda Waxman and her children David and Chayele, a few years before the family emigrated to Montreal. |

||||

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Ożarów, Poland

Ożarów, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2024 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 6 May 2017 by LA