|

|

|

[pp. 109-110]

[pp. 111-112]

[pp. 113-114]

The Editors

This memorial book is the only headstone that we can erect for the victims/martyrs of our town, whose ashes were dispersed by the wind. So long as there are still living witnesses, our holiest obligation is to amass all possible materials, everything that we remember, know, and feel about our town.

We are not professional writers, not historians. Only the shocking anguish in the appearance of the horrifying holocaust opened up our mute lips and made them speak. Every single note, when it is even recorded with a mild smile and light humor, is indeed an expression of concentrated feelings of trouble. Furthermore, every line, every memory, has its place of worth/value in this headstone-book, as a remembrance of our nearest and dearest.

Only a few Jews from Bursztyn were saved from the Nazi murderers; several only remained alive so as to relate about this holocaust. In Bursztyn, just as in hundreds of other cities and towns in Poland and Galicia, there are no more Jews. Furthermore, it took so many years following the Hitlerist flood, until we had found the strength within ourselves to gird ourselves and muster the strength to erect this monument, the memorial book of our town, Bursztyn.

It is clear and understandable that in most of the descriptions and accounts, which are contained within this book, one hears the lament of mourners; in the memoirs, everyone will hear the tone of eulogy and elegy, the lament of the horrible holocaust, as with the general tragedy of European Jewry, bound up with personal tragedy, with sorrow for our own and near ones. Here and there, there are perhaps repetitions of descriptions and of reference to the same matters, events, and people. But each one completes the other, and creates a picture of the way of life, of the disappointments and achievements. Everything together tells us how much we lost, how great, and literally, how incomprehensible the loss is!

Also mentioned in this book are Jews and Jewish life of the neighboring towns and villages, such as: Rohatyn, Bukaczowce, Bolszowce, Halicz, Jezupol [Pol.]/Azipoli [Yid.], Uscie Zielone, Tysmienica, Mariampol, Dem'yanov, and other towns, which were brothers of Bursztyn, and benefited from it

[pp. 115-116]

socially and culturally. May the kinsmen from these truncated and decimated Jewish towns, like rescued Holocaust survivors, wherever they presently find themselves, consider this Bursztyn memorial book as a monument to their most beloved and dearest ones.

With downcast heads and broken hands we stand before the modest monument for our annihilated Jewish community of Bursztyn. We unite with the holy remembrance of the murdered victims/martyrs. Sadly lost and not forgotten!

May this memorial book be an eternal reminder for generations to come, which will see in this very book, a document and a mirror of a rich way of life, which is no more.

May this lament, which ascends from this book, not be silenced and not stop demanding one's due for generations to come.

[pp. 117-118] [pp. 25-52 - Hebrew]

Dr. N. M. Gelber

The town of Bursztyn was built along the shores of the river, Gnila Lipa. On a large part of land there were pools of fish. The town lay beside the shore of the river, along the Rohatyn-Lemberg route. In the 16th and 17th centuries Bursztyn played an important role in the commercial import and export of Ruthenia. Through Bursztyn, the merchandise was delivered from Lemberg to the lowlands. It was there that the road split into two directions: one to Zloczew-Zaleszczyki, and from there, by way of Walachia, to Constantinople. The second – to Przemyslany, via Rohatyn – Bursztyn – Kalusz, Stanislawow, Kolomyja, [all the way] to Hungary.

In the 17th century, Bursztyn was a small town and belonged to the district head of Halicz. It was called Nowe Sioto. It was the property of Mikolaj Sieniawski. In 1505, 104 peasants lived there. At the top stood a “Wojt” [a high administrative officer of a Polish community]. In the same year, Zygmunt-August, the King of Poland, bequeathed estates to the brothers of Mikolaj: Prokop – the town of Ostrow, and Aleksander – Dolfojew [Dolzhka?]. Mikolaj received the entire district of Kaniuszki and the town of Bursztyn, and all the surrounding villages.

It is difficult to determine whether there was a Jewish settlement there at that time. There are no signs [of this], such as: privileges and documents to verify this. The Jews settled in Bursztyn at a later period, when the Jews of the district of Lemberg dispersed into the eastern parts of Poland.

In the 17th century Bursztyn suffered from the Tatar occupations. In October 1629, Stefan Chmielewski overtook the Tatars, drove them out from the area, and grabbed all the spoils, which they had stolen from there.

In the 17th century the economic situation sharpened in Ruthenia, so much so that the council of the district of Halicz, to which Bursztyn belonged, decided during a meeting on the 29th of July, 1681, to free the towns of Bohorodczany and Bursztyn, from paying taxes.

In the beginning of the 18th century, Bursztyn and its environs belonged to Castellan [i.e., the governor of a castle] Pawel Benoi of Warsaw; who was the castellan who built the Church of the Trinitarian Order. He took upon himself the task of liberating captives, who had been captured by the Turks. His daughter married Marshal Franciszek Rzewuski, and he received the town of Bursztyn as a dowry. From then on, Bursztyn was the property of the Rzewuski family – until the beginning of the 19th century. From the Rzewuskis, Bursztyn was handed over to Count Skarbek. And later on, it became the estate of his grandson, Prince Jablonowski.

In the middle of the 17th century, the Jewish settlement in Bursztyn was established upon the foundations, according to the model of noble towns [towns belonging to noblemen] of that time: the majority earned their livelihood by petty trade, village peddlers, tavern owners, and only a small portion took up artisanship. The leadership of the community was organized in the same manner as in all the communities in Ruthenia: at the peak stood the “Kahal” [official, designated Jewish community, recognized also by Gentile society], which was elected according to the statute that was enacted in 1630 in Kulikow, via 6 voters, in the following manner: in one of the election

[pp. 119-120]

ballot boxes, were [voting] slips with the names of the distinguished landlords/proprietors and trustees; in the second ballot box were the names of the officials and members of the commissions; in the third ballot box – the names of all the tax payers. Afterwards, two slips were removed from the first ballot box, and the rest of the slips were thrown into the second ballot box; then, they withdrew from the second ballot box two slips, and the remaining ones were thrown into the third ballot box; from there, two more slips were withdrawn; all six were those of the voters, and they nominated the new “Kahal.”

At the head of the Jewish community stood 3-5 elected heads of the community, who needed to be approved by the lord of the town. The elected heads carried out their functions every month, each one according to his place in the queue. During the time that he served officially, he was called the “month's elected head.” A portion of the elected heads would govern and carry out their functions with power/influence. In the Jewish community of Bursztyn, however, there were none as powerful/influential as Zalmen, the son of Wolf from Drohobicz, who was known for his cruelty, during the years 1750-1760. Up until the final years of the First World War, special songs were sung about him in the Ukrainian villages.

Aside from the elected heads, there were 5-7 distinguished landlords/proprietors in the Jewish community council, and for specific functions, special trustees were elected: “trustees of the great charity,” who concerned themselves with charity and the poorhouse, hospitals/infirmaries and the free burial society; oversaw the accounts and marketplace, weight, and hygiene; trustees of the Talmud Torah and the synagogue.

During times of exceptional circumstances, such as wars, Tatar and Ukrainian takeovers, from which this eastern town greatly suffered, trustees were elected who concerned themselves with the liberation of captives.

In practically every Jewish community, money was collected for the impoverished of Israel, which was sent to the “Mara D'Atra Kadisha” [i.e., a title of honor bestowed upon a Torah scholar and Jewish community figurehead] of Lemberg. Aside from the city's rabbi, there was a religious court of law of rabbinic judges.

The communal matters lay in the hands of a religious scribe and beadle, and in the smaller Jewish communities there was merely a lobbyist/intermediary.

Within the Jewish community there were various societies for good deeds and the study of Torah.

The synagogue was built in the first half of the 18th century, in accordance with the tradition of the Jews of Bursztyn in the old Jewish cemetery, founded more than 400 years ago. The cantor, R' Itzik-Dovid told Rabbi Meir Landau, many years prior to the First World War, that he had seen a headstone in the Jewish cemetery with the engraved name of the deceased: the son of the Gaon Mahar”m [Maharam] of Lublin. Rabbi Landau deduced from this that the Jewish cemetery had already existed 400 years earlier.

The conclusion that the Jewish community had existed, already at the end of the 16th century, is, however, not acceptable. First, in the archival documents, which refer to the old East Galician Jewish communities, Bursztyn does not figure in at all: second, [the notion that] Rabbi Meir, son of Gedalia (Mahar”m) of Lublin, lived during the years 1558-1616, is indeed not possible, if his son died 400 years ago.

To the Jewish community of Bursztyn also belonged the Jews who lived in the villages: Nastaszczyn, Junaskow, Sarnku, Ozieran, Kuropatnyky, and Tenetniki.

According to the accounts that remained among the Jews of Bursztyn, the Jewish community suffered greatly from the Cossack attacks of 1658.

The Jewish populace grew, not only in number, but it also respectfully sustained the Jewish autonomous institutions. The Jewish community representatives took an active part in the regional council.

In 1714, the assembly of the “Council of the Land of Reissen” was convened in Bursztyn.

[pp. 121-122]

From this, one may derive how important and significant the Jewish community was.

The major Hetman Adam Michal Sieniawski called together on 27 July, 1713 in Bursztyn, the council of Jewish communities of the district of Ruthenia, Podolia, [and] Pokucja, so as to – as is stated in the order of the assembly – “The Jews from the [afore]mentioned places shall in an urgent/pressing manner uphold an assembly on my estate of Bursztyn of the council of the land with the goal of distributing the contributions and receiving an assignation of payment, which was issued to them, according to the lists of the appraisers and their chief writer.”

Bursztyn stood opposite the cities of Rohatyn and Podhajce, the main points of the Shabbetai Tzvi movement, and later on, of Jacob Frank. Their missionaries also attempted in Bursztyn to sway people.

Elisha Schorr, one of Shabbetai Tzvi's leading believers, along with his three sons – Shlomo-Natan, Lipman, and Lieb – dispersed the belief in Sabbatianism and Frankism from Rohatyn. They moved about among all the Jewish communities in the area, and preached their [own version of the] Torah.

It is not known whether they had any influence upon the Jews of Bursztyn, and they succeeded in capturing people there, but the fact is that in the Frankist lists of converted [apostate] Jews following the dispute, which took place in Lemberg from 17 July – 10 September 1759, not a single Jew from Bursztyn was found; this demonstrates the complete failure [of the Sabbatians].

At that time, there was a rabbi in Bursztyn, Rabbi Tzvi son of Natan. Along with two Jewish community leaders and a beadle, he verified by way of an oath [taken] at a census on 15 February, 1765, “We recorded [accounted for] all the Jews from big to small, in their residences, in the villages [that stand] opposite, which are included as part of the Bursztyn Jewish community; as well as those situated along the way; we did not exclude anyone.”

At the time of the census, which was taken for a head-tax, there were in Bursztyn, proper,

438 adult Jews and 154 children. In seven villages that belonged to the Jewish community of Bursztyn – 43 [adult] Jews and 5 children.

On account of the dearth of believable/reliable documents and sources, we lack information regarding the development of the Jewish community of Bursztyn. It is only known that the influence of Chasidism grew stronger with time, among the [Jewish] residents of Bursztyn, and also lasted into the periods of Austrian rule.

The owner of the city – the Rzewuski family needed the Jewish residents, who, with their merchandise, improved the economic situation in the area. Therefore, they gave the Jews separate privileges: they built stone houses for them, some of which still remained until the end of the Second World War. Economically, the situation of the Jews of Bursztyn was very good. Their livelihood supported/aided them against the peasants in the area. They mainly took up merchandise pertaining to agriculture/farming and tavern-keeping. However, they suffered heavily from the taxes that were then placed on Jews. Aside from the head-tax, they still had to pay various other taxes.

Following the first partition of Poland, major changes took place in the land and in Galicia, from which Bursztyn also greatly suffered.

Until the year 1785, the Jews of Galicia were organized according to the Jewish law of Queen Maria Theresa, of 1776, in a separate body: the main leadership of the Jews of Galicia, which stood at the highest point. The organization was initiated in 1785, and no other institution was founded in its place. In average-sized and small Jewish communities like Bursztyn, stood three community leaders at the peak. Their task was to take care of Jewish community matters. At that time, Bursztyn belonged to the province of Brzezhany. The Jewish community did not have a rabbi,

[pp. 123-124]

only an adjudicator of Jewish law, who did not receive a salary, merely a residence. In the provincial city of Brzezhany, there was a rabbi of the province. His annual upkeep came to 200 florins and an official residence.

In all the cities of the Bursztyn area: Bobrka, Chodorow, Strelisk, Przemyslany, Podhajce, [and] Rohatyn, there were no rabbis, only religious law adjudicators.

Just as in all the Jewish communities of Galicia, aside from the standard taxes, a “bowing fee” and a “concession fee” were also placed upon the Jews of Bursztyn. For permission to marry off a son – one had to pay according to the family's earnings. Whoever married off his children without the [controlling] power's permission, was seriously punished – even to the point of seizing his property.

At that time, the Jews of Bursztyn suffered greatly from postmaster Röttel [i.e., presumably a non-Jew], who would inform on them. For every “transmission” regarding a non-official marriage, he would receive a reward from the authorities.

King Joseph II gave an order in 1782 that Jewish land workers only needed to pay half of the marriage tax. He also promised them that in a short time he would totally free them from this tax. The government wanted to give the Jews strength, so that they would invest themselves in agriculture/farming.

The [ruling] power also prepared a plan to establish economic settlements/colonies for Jews. In the spring of 1786, the first Jewish settlement was established in the village of Dabrowka, near Nowy Sacz (Santz), and later, “New Babel” (New Babylow), near Bolechow. There were also a number of other small settlements that did not exist for long.

The government's plan confirmed that from the general number of 1,400 families, which the Jewish communities had to mobilize for the agricultural settlement, the province of Brzezhany (10 Jewish communities) must give [this to] 69 Jewish families, who had intended to settle on 49 tracts of land. They were supposed to receive 66 homes, 66 granaries, and stalls, 66 work machinery, 124 horses, 88 oxen, [and] 147 cows. At the distribution, the Jewish community of Bursztyn offered up 7 families, together: 9 men, 9 women, 2 girls, and 8 boys – they received 7 portions of land, 7 homes, 7 granaries, and stalls, 7 work machines, 14 horses, 20 oxen, and 23 cows.

According to the official report of the [ruling] powers, these families settled upon their privately owned land until the end of 1793.

In 1822, from among the 60 [Jewish] families of the district of Brzezhany, 40 of them remained in agriculture. –Thereby, it is not known how many of them hailed from Bursztyn.

The budget of the Jewish agricultural settlement was placed upon [assigned to] the local Jewish communities. The settlement expenditure account for one family reached a sum of 200 florins.

As mentioned, the Jews of Bursztyn, just like those of other Jewish communities in Galicia, suffered from the heavy taxes, which led them to economic collapse.

Aside from the “Tolerance Tax” (Toleranz-Steuer), the Jews paid various other taxes, such as: the cost of kosher meat, for lighting candles.

Aside from tavern-keeping, the Jews of Bursztyn were involved in petty trade and village peddling, [and] in the sale of agricultural products. The geographical position of Bursztyn, which lay along the main highway, created economic opportunities to concentrate various branches of trade in Jewish hands.

“The Order Concerning Jews” of King Joseph II (of 20 March 1785) forced the Jews to create their own schools. In the district of Brzezhany, during the years 1788-1792, schools were created among the Jewish communities: Brzezhany, Rohatyn, Podhajce, Bobrka, [and]

[pp. 125-126]

Rozdal. Bursztyn, a small Jewish community with a small number of residents, did not merit a general Jewish school.

In 1812, the [ruling] power of eastern Galicia carried out a census. It is understood that the census was made with the purpose of collecting taxes. The census revealed that in Bursztyn there were 100 Jewish families, among them – 197 men, 216 women – in total, 413 people. In comparison to the last census of 1765, (453 people) [this] was, according to the census of 1812, a decrease of 40 people (10%) from the Jewish population of Bursztyn.

III.

In the second half of the 18th century, one of the famous rabbis of the Jewish community was Rabbi Tzvi-Hirsh son of Natan Ashkenazi, who in 1765 had signed the census list.

Rabbi Tzvi-Hirsh son of Natan Ashkenazi was the grandson of “Chacham Tzvi” and the brother of Rabbi Yabetz. His father was a large figure in Torah, one of the wise men of the religious house of study in Brody. He would give sermons about Halacha [Jewish law] and Aggadah [rabbinic homilies of various sources] before the wise men of the study house; his commentaries appeared in the booklet, “Imrei Noam” (compilations from the great men of that generation).

His mother was the daughter of R. Moshe of Brody.

Rabbi Natan had three sons: R. Ephraim, one of the wise men of the study house and a religious preacher in Brody, R. Moshe, the head of the religious court of law of the Jewish community of Zborow – the father of R. Yaakov of Lissa (Lorberbaum), the author of “Chavat Daat” and “Netivot Hamishpat” – and R. Tzvi Hirsh, the head of the religious court of law of the Jewish community of Bursztyn.

When R. Tzvi-Hirsh son of Natan died, his son-in-law, R. Yosef Teomim, was elected the rabbi of Bursztyn (R. Yaakov of Lissa was his student).

Following R. Yosef Teomim, R. Yosef Schwartz, a student of R. Yaakov of Lissa, inherited the rabbinate seat. He led the rabbinate for many years in the city. When he was elderly, in the year 1857, he made Aliyah to Israel.

R. Meir Landau (1830-1907), [was] the son of Rabbi Mordechai Ziskind Segal- Landau, the head of the religious court of Stryj (along with the head of the religious court of law, R. Enziel). His mother, Hinda, was the daughter of the rich man, R. Hirsh Hirtzman of Bursztyn, having been born in Grodek-Jagielonski. He moved to Bursztyn and became one of the wealthiest individuals in the area.

Rabi Meir Landau was born in Bursztyn. At the age of 20, he was already rabbi of the town of Knihinicz, not far from Rohatyn. In 1857, he became rabbi of his town of birth, Bursztyn. (The Chasidic rabbi of Stratyn, R. Avraham son of Yehudah-Tzvi, wrote to his followers in Bursztyn, and ordered them to be on his side). For 40 years he oversaw the rabbinate, until 1898, when his son was elected the rabbi of Bursztyn, while his father was still living. Rabbi Meir Landau died 10 Nisan 5667 [25 March 1907]. His son, R. Moshe-David Landau, took his place. R. Moshe-David's wife was the daughter of Rabbi Naphtali-Hirtz Landau of Strelisk, the grandson of R. Yoel-Moshe. During his time, the well-known religious judges were: R. Leizer Yaakov, R. Chaim-Yudl Deichsler, [and] R. Leibl Jupiter.

R. Moshe-David was rabbi in Bursztyn until 1927, when he died.

In 1910, following the initiative of R. Shmuel, the son of the Preacher of Strelisk, R. Yoel Ginzburg, the head of the Mesivta of the Brzezhany Yeshiva of the Gaon, R. Shalom-Mordechai Schwadron, was invited to Bursztyn. Following his sermon, he was taken up as the city's adjudicator of religious law, and filled this position until the annihilation of the Jewish community.

Prior to the revolution of 1848 in Austria, there was a difficult struggle during the lifetime of Galician Jewry between the religious and Chasidim from one side and the Maskilim [the Enlightened Ones] from the other side. The Jewish community of Bursztyn

[pp. 127-128]

did not appreciate the flavor of this struggle. Its inner life was entirely influenced by Chasidism.

Already in the beginning of the 19th century, Chasidism set down roots in Bursztyn. The founder was R. Yehuda-Tzvi-Hirsh Brandwein from Stratyn, a student of R. Uri Strelisker, known by the name “Saraf,” a student of R. Shlomo of Karlin. His eldest son, R. Avraham, inherited the rabbinic seat from his father. His brother, R. Eliezer (Leizerl) was the Chasidic rabbi of Jezupol. He had two sons: R. Uri, his successor in Jezupol, and R. Nachum.

|

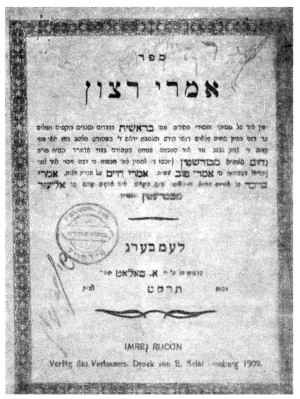

R. Nachum became the rabbi of Stratyn in 1865, when he was 18 years old. A few years later he relocated to Bursztyn, and was rabbi there until 1914; he was a diligent Torah scholar and a Kabbalist. He wrote 4 books regarding the Kabbalah: 1) “Imrei Tov,” 2) “Imrei Chaim,” 3) “Imrei Bracha,” 4) “Imrei Ratzon.” R. Nachum established a stunning [rabbinic] court in Bursztyn. There was always a large number of “residents” whom the rabbi supported. In the Bursztyn and Rohatyn area there were many of his followers, who formed local “Bursztyn study houses” – in Rohatyn, Bukaczowce, Bolszowce, Halicz, Bukaczowce, Bolszowce, Jezupol, Monasterzyska, Nizniow, Nadworny, Łysiec, Tysmienica, Stanislawow, Uscie-Zielone, Mariampol, and Podhajce.

The rabbi's court and the large number of arriving Chasidim/followers contributed to the economic existence of the Jewish community of Bursztyn.

In the summer of 1914, while the Chasidic rabbi was at his country house in the mountains, a fire broke out in Bursztyn, which destroyed half of the town, and the rabbi's court was also consumed. At that time, R. Nachumtze left Bursztyn and moved to Stanislawow. He died there in 1915. He left behind a son and four daughters.

His son, Leizerl, took his place in Stanislawow. His sons-in-law: 1) R. Aizikl of Podhajce, 2) R. Ephraim Horwicz, rabbi of Uscie, 3) R. Leib, the Chasidic rabbi of Olyka, 4) R. Moshe-Lieb, the Chasidic rabbi of Schatz [i.e., the city of Suceava, situated in the historical regions of Bukovina and Moldavia].

Following R. Nachum's death, his followers [or Chasidim] broke into three “courts”: one – of R. Leizerl, the second – of his son-in-law, R. Aizikl of Podhajce.[2]

In the beginning of the 1930s, R. Moshe, R. Leizerl's son, renewed his grandfather's court in Bursztyn. He led the rabbinate until he was murdered, along with his wife and three sons, during the murderous Nazi period. Aside from the Stratyner Chasidim, there were Belzer and Czortkower Chasidim in Bursztyn. Their influence was apparent in the life of the Jewish community until the outbreak of the Second World War.

|

|

| Rabbi Reb Moyshe'le (Brandwein) of blessed memory, the Rebbe of Bursztyn, the son of Rabbi Reb Leizer'l of blessed memory, the Rebbe of Stanisławów and grandson of Rabbi Nachum'tshe, founder of the rabbinic dynasty of Bursztyn. Rabbi Reb Moyshe'le was famous throughout Poland and Galicia and he had many Chassidim. The Nazis caught him and tortured him severely and he died in 1942 in Stanisławów |

During the years 1846-1847, the council of the Jewish community was in a difficult financial situation, and was unable to cover its expenses. The Jewish community asked for a permit from the regional leadership to increase the price of kosher meat, so as to cover the needs of the Jewish community. At the end of 1847, the regional leadership of Brzezhany allowed the Jewish community of Bursztyn to add an additional tax to the cost of [kosher] meat, so as to cover the expenses.

As is known, in 1850, Jews were permitted to purchase immoveable properties. From all the Galician cities, Jews submitted requests to the Minister of the Interior in Vienna, regarding permits to purchase immoveable property.

From the Jews of Bursztyn, there were three who submitted requests in 1864: B. Blauer, Mehrberg, and Feldklein. In 1866, Erdstein and Kimmel, major grain dealers in eastern Galicia, requested a permit to record their places and houses, in the registry of property estates. A few months later they received the permit.

At that time, there were already two Jewish physicians residing in Bursztyn: Dr. Goldscheider and the surgeon, Rittner. In 1845, Rittner did something that shook up the

[pp. 129-130]

Jewish community of Bursztyn: Rittner had a son, Edward, and when he was yet a small child, his father had him converted to Christianity. Insofar as the query why he had done such a thing, the father replied – that he had done it, due to a conviction in belief. He was asked: “Since when are you interested in religious matters, and when did you come to the conviction that Christianity is more desirable than Judaism?” Here he admitted that he did this, not because of conviction, but knowing that his son, who was very capable, would climb in life as a Catholic, and that if he were to remain a Jew – he would barely be able to become a lawyer, or a doctor with a good practice in the province.

Edward Rittner did indeed make a great career [for himself]: he joined the government service and became a lecturer in laws of the Church at the University of Lemberg. And when he turned 31, he was made a full professor. Later on, during the years 1896-1897, he became, in the government of Count Kazimierz Badeni, Minister of Galician Matters.

Dr. Rittner had a major influence in government circles, and was one of the confidantes of Kaiser Franz Joseph I; when the Crown Prince Frederick grew very ill, and his brother Otto was elected to temporarily take his place, Kaiser Franz Joseph ordered Rittner that he broaden [i.e., educate] him for his forthcoming position.

When Professor Dr. Rittner died on 26 September 1899, the marshal of Galicia, Count Stanislaw Badeni, eulogized him, saying: “Rittner, the researcher, the shining jurist, possessed exceptional abilities and a show of politics, and with every matter that he oversaw, he was a loyal servant of the country” --- His son, Tadeusz Rittner, 1873-1921, was a well-known writer and dramatist.

|

Another case of Jewish apostasy took place in Bursztyn in 1858: a Jew by the name of Finkel took his child, Ludwik, to be converted. Ludwik Finkel, 1858-1930, was one of the founders of the new Polish bibliography and historiography. He studied philosophy in Berlin and Paris, and was appointed lecturer of history at the Agricultural Institute of Dublany – and in 1886 – in Lemberg.

In 1892, he was appointed a full professor at the University of Lemberg, and he was a lecturer there until 1927. Dr. Finkel was well-known as an historian among Polish historians; he wrote many studies and books about the history of Poland during the Jagiellonian period. His bibliography regarding the history of Poland (2 volumes, 1891-1914) is a foundational book, following lengthy research work, based on primary sources.

It is worth mentioning that Polish society did not know anything about his Jewish heritage.

Later on, in Bursztyn, there arose private teachers who began teaching the children of the wealthier families, general studies and also languages, German, and Polish.

To the important families belonged: Hammer, Raphael; the head of the family was the in-law of Naphtali-Hirtz Hirtzman, the city's wealthy man and son-in-law of Rabbi Mordechai Ziskind Landau from Stryj; the families: Breiter, Feldbau, Kleinfeld, Gelernter, [and] Friedlander. Along with Rabbi Landau's family, the economic and social life of the Bursztyn Jewish community was concentrated within their hands. In the city there were already progressive Jews: Maskilim, such as Shevach Klarberg, [and] the Hammer family.

[pp. 131-132]

At the end of the 19th century, there stood at the head of the Jewish community: Moshe Hammer, Yonah Feldbau, [and] Shevach Klarberg. In 1903, the Austrian ruling powers oversaw elections for the cultural council. Elected were 12 members of the council, among them: Moshe Hammer, Yonah Feldbau, [and] Shevach Klarberg. Elected as the representative of the Jewish community council was the pharmacist, Tierhaus; his position representative – Zelig Hammer.

|

|

Little by little, the aspiration toward the Haskalah [i.e., the Jewish Enlightenment] penetrated the Chasidic town of Bursztyn, into the upbringing of the youth, in the spirit of the times.

In 1898, there opened in Bursztyn – as demonstrated by the efforts of a small group of Maskilim, at whose peak [stood] Shevach Klarberg and Dr. David Maltz – a Jewish school for boys, founded by the “Baron Hirsch Foundation,” which initiated educational activities in Galicia and Bukovina since 1801, and built 37 school buildings. In 1901, the number grew to 50 school buildings.

The director, Antshl Fogel, taught the students in the Baron Hirsch School farm labor.

The studies were well received, and the religious elements also sent their children to the school.

The Baron Hirsch School existed until the outbreak of the First World War, 1914. After the war, the director, Fogel, worked as the secretary of the Jewish community of Lemberg.

The Jewish community took over the school building. The Peretz Association and the Peoples' Library were located there.

“IKO” [Jewish Colonization Organization] created loan offices in Galicia in order to provide financial aid to the artisans, petty merchants, and village peddlers. At that time, in April 1905, according to the initiative of Director Fogel, an “IKO” loan office was founded in Bursztyn. The overseers of the loan office were Antshl Fogel and Fishl Rottenstreich.

Aside from the “IKO” loan office, there also existed a cooperative bank; people called it “The Lowest [Level] Bank,” because the bank was located in the cellar of Leizer Landner's house. The directors of the bank were: Zalmen Stern and Zelig Hammer. The members of the supervisory council – [were] Berish Gelernter, Berish Hornik, Avraham Eli Tobias, and Avraham Frisch.

The loan office and the cooperative bank were active until the outbreak of the First World War. In 1918, both of the institutions were consolidated into the single “Cooperative Loan Office,” at whose helm stood Dr. Rurberg, Zelig Hammer, and Dr. Wolf Shmarak.

An ebullient national [way of] life began in Bursztyn with the establishment of the Zionist organization, “Chovevei Tzion.” The founder was Bunem Schapira, an educated person in whose home Bursztyn's youth assembled, and Schapira would read them Bialik's poetry. Among the youths were: Tauber, Zalmen Stern, Meir Redisch, Moshe Schumer, David Frankl, Yisroel Jamper, [and] M. Tobias.

In 1900, Dr. David Maltz moved to Bursztyn and opened his legal office [practice]. With him, the city acquired a Jewish-Zionist personality, which had since 1882 carried out important functions for Galician Jewry. He was an organizer, a speaker, and a writer with a strongly sharpened quill and a lucid style.

Dr. David Maltz was born in Lwow [i.e., Lemberg] in 1862. In 1882, he joined a group of Zionist students, who were led by Dr. Avraham Kurkis, and from then on, he belonged to the Zionist activists. He was a member of “Mikra Kodesh,” the first Zionist organization in Lwow,

[pp. 133-134]

founded by Yosef Kobak (1820-1913), Dr. Reuven Bierer, and Ozer Yehudah Rohatyner (1849-1889).

Dr. Yehoshua Thon, along with his brother-in-law, Dr. Mordechai Ehrenpreis, Adolph Stand, and Dr. Mordechai Brode, founded the organization “Tzion” (Rynek 12) in Lemberg. From there, they began to create the Zionist Federation of Galicia, several years before the appearance of Dr. Theodore Herzl.

Nearly every week, Dr. Maltz traveled to various cities to give talks and readings, propagandizing Zionist ideology, founding Zionist organizations, and societies for the Yishuv [settlement] in Israel.

In 1893, in Lwow, the first brochure [bearing] the contents of the Zionist program, entitled “What Should Be the Program of Jewish Youth?” [was issued]. Dr. Maltz wrote the chapter there concerning Israel and the colonization of the country. Even then, he was already considered one of the best Zionist writers. His articles in “Pszyszloszcz” and “Self-Emancipation” under the editorship of Dr. Natan Birnbaum made a strong impression with their ideological clarity and sharp polemic style, against the assimilationists. His articles provided a serious contribution to deepening the Zionist ideology among the Jews of Galicia.

In 1892, the first Zionist newspaper, “Pszyszloszcz” (Future), appeared in the Polish language. It was mainly dedicated to the propaganda among Polish-speaking circles. Dr. Maltz belonged to the most important writers there. Thanks to his sharp satirical style, he was the polemicist of the newspaper. There was not a single event in Jewish life to which he did not, in his own manner, respond. He came out especially sharp against the assimilationists and opponents of Zionism. He assaulted them mercilessly.

At the Zionist conference, which took place in Lemberg the 23-25 April, 1893, Maltz came out with an all-encompassing and sharp assault against the delegates who only emphasized Jewish nationalism, as though it had no connection to Israel; a national movement – according to his speech – “that did not include as part of its goal the renaissance of the Jewish nation in its [own] land, is foreign to the Jewish spirit. There are no prospects of dealing with the Jewish question upon the foundation of a national renaissance in Galicia. The national idea means a full-fledged solution to the Jewish question in Israel. The only means is to liquidate the diaspora and concentrate the nation in Israel.”

For this particular outlook, Dr. Maltz fought his entire life.

From 1893, Dr. Maltz, together with Dr. Avraham Kurkis and Dr. Hescheles, was the editor of “Pszyszloszcz.” During the summer months of 1893, Dr. Maltz made a big propaganda and educational advertisement trip across Galicia.

Under the influence of Dr. Herzl's “Judenstadt,” Dr. Maltz wrote a drama in Polish, entitled “Dr. Moshe Blum,” which, at the time, made a huge impact on the Jewish youth. He was elected a delegate to the First Zionist Congress in Basel (1897), in which he took an active part.

Following the congress, he was active insofar as propaganda and educational advertisement in the press. He took part in the Zionist conferences and congresses, and was a member of the country's administration within the Zionist Federation.

In 1899, Dr. Maltz became well-known for his sharp speech against Dr. Emil Bick,

[pp. 135-136]

the president of the Jewish community of Lwow, who had declared that the difference between the Jews and the Poles existed only in terms of religion.

At the Jewish Communities Conference, which took place May 1, 1900, Dr. Maltz, as a delegate of one of the Jewish communities, sharply assaulted this very theory that [caused the] degeneration of social life among the Jews of Galicia.

After he moved to Bursztyn, he was again Zionistically active in land surveying. At the conference, which took place on 16-17 June, 1901, he refereed the situation of the Jews of Galicia. Using rich historical and statistical material, he provided an overview in his lecture of the legal, economic, and cultural development of the Jews at the close of the 19th century. He established that Galician Jewry, particularly the intelligentsia, still did not understand the tragedy of the situation, and that there was no other solution, aside from Zionism. Insofar as the economic element, the Jewish populace became an extraneous matter. The Jews are pushed out of every realm, the Jewish intelligentsia distances itself from Judaism on account of fear, so that it will not need to worry about our future. At the conclusion of his lecture, he proposed an economic program, creating offices for employment mediation, organizing modern, social activities, [and] creating savings and loan offices. In the cultural realm, he demanded that they make an impact on the education of the youth in a national constructive spirit, spread education among the people.

At the conference, he was elected a member of the country's administration. At the Fifth Zionist Congress in Basel in 1901, he was elected a member of the large actions committee of the Zionist World Federation. He participated in the Sixth and Seventh Zionist Congress, where he belonged to the opponents of the Uganda Plan. Also, at the Eight Congress in The Hague (1907), he participated.

During the years 1901-1903, he took an active part in the establishment of the Zionist youth movement, particularly academically; he took part in the Zionist monthly journal in Polish, “Moriah,” which was established according to the initiative of Dr. Yaakov Thon in 1903.

At the time of the elections for the Viennese Parliament, Dr. Maltz ran as a candidate in the province of Zolkiew-Rozdal and received 1,269 votes. He took an active part in the “election fight”; politically, he was for joint action with the Ukrainians, and during the election proceedings he would speak Ukrainian.

At the Assembly of the Jewish Communities, which took place on 28 April 1908, according to the initiative of the Viennese Jewish community, with the goal of establishing a general Jewish centralized institute, which would be able to make appearances in the name of all of Austrian Jewry, Dr. Maltz represented the Jewish community of Bursztyn. Dr. Maltz is the one who brought the Zionist spirit into the general debate. At that time, he was active in the realm of politics and land surveillance, actively participated in the political conference of the national federation, which came together in Krakow on the 15th May, 1910, under the leadership of Dr. Beno Straucher, the deputy of the Austrian Parliament.

|

|

(at the end of the 19th century) Second row: David Maltz, Adolf Stand, Laufer |

Also, at the elections for the Viennese Parliament in 1911, Dr. Maltz ran as a candidate in Tarnow, where he received 1,194 votes.

At the Central Zionist Land Conference, which took place the 24th December, 1911, in Stanislawow, Dr. Maltz was

[pp. 137-138]

a presidium member, and was elected to the federation council. During the years 1911-1914, he concentrated his Zionist activities in Bursztyn.

When the First World War broke out, he fled to Vienna, where he was again active in Zionist activities, taking part in January 1914 in the assembly of the members of all the central commissions/committees in the Austrian Zionist movement. After he returned to Galicia, he again continued his Zionist activities.

However, during the war he overcame much embitterment and resignation.

In 1917, following the Russian Revolution, he did not believe that the war was close to ending. He asked: “Who can predict whether the Russian Revolution will give birth to a living tree, or to a totally poisonous plant?” Regarding the Jewish problem, he writes: “If the promise of Wilson and Lloyd George insofar as the national home in Israel is based on the truth, then the struggles [wars] and losses were worthwhile; then our children in Israel will have a worthy existence.”

I have given more attention to Dr. Maltz, because he was among the [leading] figures of Galician Jewry, and it was an honor for the Jewish community of Bursztyn to have him among its residents and to take him up as an experienced leader.

The Zionist movement in Bursztyn was, until 1914, a social, cultural factor in the life of the Jewish populace. In 1909, a Hebrew school with one teacher and 29 students was founded by the local Zionists. At the time of the First World War, the Zionist movement received an active, organizational strength in the person of Dr. Wolf Shmarak, who moved to Bursztyn and worked as a lawyer.

From an economic standpoint, the professional composition of the Jewish populace in Bursztyn did not change. The majority consisted of merchants with stores, furs, wood, grain, cows, [and] horses. A certain number of Jews ran businesses with the estate holders and worked for them as administrators and advisors regarding the sale of agricultural products.

Jews were also merchants, tailors, capmakers, carpenters, barbers, blacksmiths, and shoemakers. Of the free professions, there were three Jewish doctors, lawyers, a pharmacist, and several government officials, employed by industrial enterprises, such as Friedlander's mill.

|

|

Factually, the complexion of the city was a Jewish one. Even the letter carrier, R. Ephraim Schneider, was dressed in the Jewish manner, with a beard and sidelocks, and as is understood, did not work on the Jewish Sabbath or on Jewish holidays. Even the Christian politicians spoke Yiddish.

Among the older generation, there were religiously knowledgeable people who did not cease learning Gemara or the holy books for a single day. One could always see them in the city's religious house of study and in the houses of worship.

Aside from the Great Synagogue, in the city [there] was the rabbi's little synagogue, a religious house of study, and the houses of worship of the Zydaczower Chasidim, of the Czortkower, and the Stratyner; a Halicz house of worship, a Polish house of worship, which was established by Mendl Polak, the house of worship in the religious house of study, and the “Tailors' Synagogue,” which was part of the Great Synagogue.

Among the societies was the Free Burial Society, which was overseen by Yonah Geller, the Talmud Torah with Yehoshua Hammer at the helm, “Bikur Cholim” under the leadership of David Bauer; “Yad Charutzim,” “Dorshei Tov,” “Linat Hatzedek”

[pp. 139-140]

(an organization of artisans), the Women's Association, of which Sarah Hammer was the president.

Notwithstanding the major changes that took place in the lives of the Jews of Galicia during the years of the First World War, the majority of the Jews of Bursztyn consisted of Chasidim. Approximately 90 percent was traditionally dressed. Although in Bursztyn the rabbis of the Brandwein dynasty “reigned,” many Jews were followers of our rabbis.

During the years 1912-1913, the Jewish community numbered 560 tax payers. At the peak of the Jewish community's board stood Zelig Hammer.

During the years 1880-1910, the Jewish population grew in comparison to the others [other populations], according to the following numbers:

| Year | Population Number |

Poles | Jews | Others |

| 1880 | 3,953 | 522 = 13.2% | 2,017 = 53.3% | ---- |

| 1890 | 4,209 | 453 = 10.8% | 2,174 = 51.7% | ---- |

| 1900 | 4,438 | 541 = 12.2% | 2,209 = 49.8% | ---- |

| 1910 | 4,896 | 654 = 13.4% | 2,245 = 45.8% | ---- |

| 1921 | 3,581 | 1,431 = 37.4% | ---- |

During the years 1880-1910, the number of Ruthenians grew from 1,324 in 1880 to 1,996 persons in 1910. That is, from 33.5%, it increased to 40.8%. In truth, the number of Poles increased from 522 in 1880, to 654. That is, from 13.2% to 13.4%. In contrast, the number of Jews decreased percent-wise from 53.3% in 180, to 45.8% in 1910, although the absolute number rose during the course of this period from 2,107 to 2,245 people in 1910. In 1921, there were 1,341 Jews among a population of 3,581. In contrast to 1910, the number fell from 45.8% to 37.4%.

An absolute growth both in number and in percent occurred only among the Ruthenian population.

The war during the years 1914-1918 brought with it the utter destruction of the city and of the Jewish population. Heavy battles took place around the city. A large number of Jews fled from the city, westward. A portion of them spent the war years in the refugee camps in Bremen, Moravia, and Austria. A portion managed to reach Vienna.

Following the war, a portion of the Jews of Bursztyn returned to Bursztyn.

Following the fall of the Hapsburg Monarchy and the declaration of the West Ukrainian Republic within the realm of eastern Galicia, “Jewish National Boards” were created in the cities with a Jewish population. In Bursztyn, at the head of the “Jewish National Board” stood Dr. Wolf Shmarak.

During the periods of Ukrainian rulership, the Jews suffered from the difficult economic situation and from the weakness of the central powers in western Ukraine, which could not restrain the anti-Semitism and rampages of the apparatus and military against the Jewish populace.

Before the Poles marched in, Pyetlura's military in eastern Galicia staged pogroms against the Jewish populace in the cities of Bolszowce, Bukaczowce, and Bursztyn, in which 11 Jews were killed. Also, when the Poles conquered the city, the Jews of Bursztyn still did not have any calm or peace.

Translator's Footnotes

[pp. 141-142] [pp. 53-62 - Hebrew]

Dr. Mordechai Haber

If I needed to characterize in a few words the town and its people, I would do this with a single word: readiness-to-help [in Yiddish it reads: “hilfsgreytikeyt”]. Everyone together and everyone individually was always ready to help one another.

The older generation referred to the town as: Little Jerusalem. For over four hundred years, Jews lived in this town. Generations of religious learners and common folk were raised with joint pain and joy, strange conflicts, and arguments, and yet, with so much closeness and love.

I do not know when Bursztyn received the character and name of a town [shtetl]. It is accepted that it was founded in 1654, when Count Potocki created it in the name of his son, and called it Stanislawow. At the same time, Prince Jablonowski invited Jews to come reside at the boundaries of his principality. With this, he had as his goal to develop both trade, as well as artisanship. At that time, Jews were marked as part of the Prince's property, and not as part of the general population.

From headstones in the old Jewish cemetery, we can derive that already in the 16th century Jews resided in Bursztyn. It is, however, possible that this cemetery was not the first one. Also, the old synagogue bore the seal of Romanian architecture of the 17th century. According to the legends that the old folks would relate, Bursztyn was already a large Jewish community, already four hundred years ago.

Geographically, Bursztyn lies between Lemberg and Stanislawow. With the train line it is 96 kilometers to Lemberg; to Stanislawow – 38. There is also a nicely paved highway that connects Bursztyn to these cities. Jews thoroughly resided in the center, where the businesses and shops were located. They worked in all sorts of areas: manufacture, living means, ironworks, leather [work]. There were barbers, tinsmiths, capmakers, tailors, and shoemakers.

In the middle of the circle stood a row of wooden barracks, which were designated for stores. Moshe Feld's tinsmith workshop, Mechl Drimmer's tavern, Moshe Feldbau's butcher shop, [and] the large house of the Hammers were also situated there. Beside Nachman Breiter's house stood the “cabs.” This is how they referred to the carriages.

From the city to the train station it was approximately six kilometers. There was also a train station beyond the village of Demianow. In the city, people said that during the process of building the train line, Prince Jablonowski resisted, with the motive that this would disturb the peace of the populace. And he followed through [on this]. They needed to build it six kilometers further away. Beside Mechl Drimmer's tavern stood the porters with their wagons. Standing there were: Yudl Ripacz [sp.?], Moshe from the holy place [likely a reference to the Jewish cemetery], Raphael Isaac, and others. Somewhere further along, next to Nachman Breiter, stood the simple porters: Shachna-Shlomo Machnicki, the small Moshe-Leibl, Hersh Itche's brother-in-law, and others. They were heroes, always bound up in thick twine, and carried the heaviest loads upon themselves, which they carried [to their owners] for earnings of a few groshen [i.e., a pittance].

It was here that Miriam the booth keeper had her kiosk with

[pp. 143-144]

fruit and bread; Leibl, the beadle's wife and other wives who worked hard for their husbands, or widows – for their children. Every Tuesday was a market day. Farmers and traders from various surrounding towns who planted their booths in the middle of the circle came.

Jews also lived in the surrounding villages: Demianow, Martynow, Wochowka, Kuropatniki, Korostowice, Sarnki, Ludwikowka, Nastaszczyn, and others. From the three villages with the name Demianow, there was one village, in which the peasants would not allow any Jews to dwell. On Shabbat [the Jewish Sabbath] the Jews from the villages would come into the city to pray. They belonged to the Jewish community of Bursztyn.

The number of the general population in the town with the peripheries was estimated at 6-7 thousand. Of this, fifty percent were Jews.

The previous generations in the town were not involved in any politics. However, they led vivacious, social activities. There existed various welfare offices, a Linat Hatzedek, whose function was to remain vigilant about ill members. There was an organization, “Hachnasat Kallah.” Every Friday, homeowners/proprietors went around collecting donations for poor brides. Every year before Pesach, the adjudicator of Jewish law, Yoel Ginzburg, Yaakov Rude, and Yossel Mintz went around town collecting Maot Chitin for Matzot [Matzos] for poor people.

Pogroms

During the First World War, when the Russians took over the town, the Cossacks engaged in robbing Jewish homes, raping Jewish women. It so happened at the time, that a Jewish girl who had freed herself from the hands of a Cossack, fled to the Jewish study house, which was located in the home of my grandfather, Moshe Haber. The Cossack chased after her. Following the cries of the girl, my grandfather ran in. He was at the time already 75 years old, but a fit and strong person, and with force, he tore away the Cossack from the girl, who immediately took flight. The Cossack, filled with murder, attacked my grandfather with his sword, beating him up very badly. From these beatings he grew seriously ill, and a short time later, he died.

In the town there was a bank founded by IKO [i.e., Jewish Colonization Organization]. This was located in David Neiberger's [Neuberger's] house. The artisans also had their own loan office.

In this manner, the town lived calmly, [with] each one helping the other. Only when it came to electing somebody for the Jewish community, or for the [position of] a synagogue or religious study house trustee, did moods grow excited, and stormy arguments flared up.

In the synagogue building there was an anteroom in which artisans would pray. Nute the tailor was the trustee. His representative was Fishele, also a tailor. During the holidays, they all prayed in the synagogue. They would sit on the benches in the very back, not feeling as at home as in the anteroom.

The conflagration during the time of the First World War also affected both of the religious study houses. The large study house they rebuilt following the war. In contrast, the smaller one, due to a conflict with A. Breiter, was not rebuilt. Jews looked with mournfulness at the destruction.

The city had an important rabbi, a big scholar, Rabbi Moshe David Z”L [i.e., “May his memory be for a blessing.”]. In his younger years he lost a leg, and walked on stilts. He benefited from the greatest respect from the entire Jewish populace, not only from the town, but also, from the entire area. Following his death, his younger son, Herzl, following another bitter argument, became the rabbi. There was also an adjudicator of Jewish law, R. Yoel Ginzburg, Z”L. His two sons and daughter all received a secular

[pp. 145-146]

education; and for this reason, he had to withstand much trouble and many insults from the Chasidim in the town. Aside from three religious slaughterers, there was also a trustee, a relative of Shalom Baumring.

At the entrance to the Jewish cemetery, there would be a lot of poor people standing, waiting for a funeral, or visitors on [the occasion of] a Yahrtzeit. One could sometimes also see a volunteer there with a plate for the Keren Kayemet for Israel.

The Jews of Bursztyn were generally calm people, but not cowards. In necessary cases, when there was some threat of danger, the Jews of Bursztyn were always prepared to defend their lives and their honor.

Prince Jablonowski, a religious Catholic, only settled Catholics upon his estates, who parted ways with the Ukrainian Protestants; this purely Polish village was called Ludwikowka. He did this with the express intention of creating a safeguard against the majority of Ukrainians, so that in a situation of need, he would have whom to support himself. He brought the new Polish peasants from eastern Poland, built huts for them in this village. Among the new transplants, were also weavers. Summertime, they worked in the prince's fields, and wintertime, they wove materials for the peasants out of linen from the surrounding area.

Prince Jablonowski always looked for a way to ease the lives of the Polish peasants. And he decided to build a water mill for this village. For this purpose, it was necessary to dig out a new bed for the stream, which would fall into the Dniester. At that time, he brought up many Tatar laborers, who were, however, poorly paid.

As customary, their wrath was taken out on the Jews, and the Tatars began preparing for a pogrom. Also joining them were Polish peasants, and they plunged down upon the town.

In the beginning there was chaos. Jews hammered up their stores and secured themselves inside of their homes. The infuriated Tatars, along with the Poles and Ukrainians, ran wildly through the streets, hitting [window] panes. However, at some point they came upon the Jewish workers of Moshe Feldbau's butcher shop, which was located in the [town's] center. Joining them were other Jews, armed with knives, hatchets, and other work tools. They threw themselves upon the Tatars, who quickly withdrew; and running from fear, they fell, one on top of the other.

On the way, they encountered a Jewish coachman who was driving from Kalisz with his horse and wagon. He was transporting salt for Yehoshua Kletter. A whole crowd of frenzied Gentiles pounced upon him. But he did not lose himself, quickly tore out a wagon shaft from the wagon, ready to defend himself. Also here, the Tatars right away, after the first blows, withdrew.

The uprising of the Jews of Bursztyn came to them unexpectedly. They knew that one can beat and murder Jews without fear of receiving any punishment. The strength and heroism of these Bursztyn Jews was for them an enormous surprise. For the first time, these pogromists felt that they were threatened with danger for their own lives, and in great panic, they fled. The town emerged with small losses. In the meantime, a gendarmerie arrived from Rohatyn. In the town there was complete calm.

This occurred at the end of the 19th century. Many years later they still spoke about this case in the area. The heroism of the Jews of Bursztyn also served as encouragement for the surrounding Jewish towns.

Jewish Heroes

In the town there were two families, which were exclusively involved in the horse trade.

[pp. 147-148]

This was the Shurkmans and the Glotzers, who were referred to as the “chatshyuliks.”[1] The Shurkmans were an old, veteran family in the town. In contrast, Wolf Glotzer came from another place, and got married to a girl from Bursztyn. All of them were eminent heroes who bestowed fear upon the surrounding peasants.

There was a Gentile, Michajlo, who worked as a guard in the city brickyard, and lived there later on with his family. He would pick quarrels with the Jews, insult them, [and] beat them up. A tall man, a strong man, he would yet like to get drunk; and at the time, there was no limitation to his coarseness/vulgarity. Nobody wanted to go near him and avoided him, until one time when he came upon one of the horse traders, who got even with him for all the times, and beat him up so much, such that he never again attempted to bother a Jew. From that time forth, the town breathed more easily.

During the years 1917-18, at the end of the First World War, fights continued for a long time between the Ukrainians, Poles, and Bolsheviks in the Bursztyn area. Because of its strategic placement, Bursztyn sustained a key position. It is clear that the scapegoat was always the Jewish population. Everybody tore pieces from them [i.e., ganged up on them]. Whichever army went through there robbed and raped Jewish women, filling the town with wailing. The women were raped in the presence of their husbands, parents, and children. The most heavily felt in the town were the Petlyura-ists. Jewish life was utterly abandoned. In the pogroms and rapes participated both the Ukrainian peasants, as well as the intelligentsia, who demonstrated the lowest degree of animalism and sadism.

The bands of the Polish, General Haller, did not fall [far] behind. They became well-known for chopping off the beards of elderly Jews. Just as in every Jewish town, the soldiers in Bursztyn also received free reign from their general, and were permitted to do with the Jews as they pleased. The town was robbed and impoverished. Many Jewish homes were burnt at the time. In addition, there was the huge conflagration of 1921, when half of the town went up in smoke. Were it not for the help of the Joint at the time, it would have spelled the complete downfall of the Jews.

The Joint, at that time, organized a peoples' kitchen in Bursztyn, which was located in the building of the Baron Hirsh Synagogue. For the homeless families, temporary barracks were erected. One of these barracks was situated on the spot of R. Moyshele's burnt-down house, next door to Yosef Shlomo Rudy. Another barrack was erected next to the Great Synagogue.

Aside from the collective help with which the Jewish community dispensed, significant help also arrived for individuals from various relatives in America, which helped a lot of Jewish families get back on their feet.

These are the sad, the tragic episodes of Jewish life in Bursztyn. But each one of us also has his nice memories, firstly, of one's childhood years.

In the Glow of [One's] Radiant Childhood Years

Like a glow was the winter with its play in Bursztyn. Just as soon as the first snow fell, we immediately took out our sleds, which nearly every boy owned. Because for whomever this was purchased, he himself mastered it, for what sort of face would winter have without a sled? This was one of the greatest pleasures, to go out beyond the city, and slide down from the mountains to the valley, flushed, screaming, frolicking, without worry. The guiltless, genuine childish joy of competition, as to who would sooner reach the designated goal. It is understood that the one who won was he who had a better

[pp. 149-150]

sled. The poor, wooden sled could never catch up with the metal-forged and precision-made one.

Occasionally, one would also hitch a ride with a coachman, who would place his wagon upon wheels and harnessed his horses, wintertime, with bells around their throats, connected to the light sleigh, which literally flew across the snowy roads. When we hurriedly got onto one of those sleighs, there was nothing that was comparable to our joy at the time.

When the river, Gnila Lipa was already well frozen, with a thick layer of ice, the soda water and lemonade dealers would break up whole chunks of ice and bury them deep in the ground for the forthcoming summer. Yosef Shlomo Rudy, Chaim Stryzower, and others concerned themselves with this.

The most freezing temperatures were [felt] during the months of January and February. However, even then, it would so happen that the sun would warm things up in the middle of the day, and from the rooftops and windows it would pound down until evening time, when the sun set, and the temperatures once again dropped. All the windows and rooftops were then covered with hanging icicles, which served as playthings for the children, the following morning.

The forest, enveloped in white, empty, even in winter, did not cease attracting children and adults to it. The starlings, which did not leave the forest the entire year, echoed with their happy chirping. An exceptional event was Shabbat Shira, when father and mother would go with us to throw crumbs to the birds, and it appeared as though all of winter's nature was singing a song, praise to heaven and to life.

A beloved place for the youth to go sledding was also situated between the Christian cemetery and the home of the Malikows, who delivered bricks for my grandfather's brickyard. Here, we felt protected against the assaults of the Polish and Ukrainian hooligans.

Beautiful, Unforgettable Figures

Small and poor was our town. However, it had splendid figures. Many years have passed and I cannot precisely recall the names or lifestyles of everyone. But they stand before my eyes, and from their figures limitless, heartfelt warmth streams down upon me.

Bursztyn was a religious Jewish town. There were many Chasidim there, who followed various rabbis, who would frequently come to the town with their trustees, stayed at [the homes of] the well-off Chasidim, and led their tables[2] there. They would come in the middle of the week and remain over the Sabbath, leading the Musaf prayer at the pulpit of the large religious study house.

Following the Sabbath the rabbi would listen to all of his Chasidim [or followers], doled out advice, and granted blessings, and in addition, accepted the donations that everyone gave, according to his ability. In addition, the trustees would also receive very fat profits.

|

|

To these beautiful, unforgettable figures belongs Moyshele Rudy, who had lost a leg in his youth. He was a great religious scholar and was loved by the entire populace. He had a small factory of soda water, which the children later took over. R. Moyshele Rudy was also a Mohel in the town, for which he did not receive any money. Following his death, Berele Haber became the Mohel, who though not such a scholar as R. Moyshele, was a very religious and honest Jew. Until the time of the First World War, he lived in the village of Svitanok, next to Bursztyn. He made his livelihood from dealing in cattle. But whenever he had a Bris, he would pass up on the very best marketplace. The good deed of [performing] a Bris stood higher for him than all material profits.

[pp. 151-152]

The Happiest Day of the Year

Simchat Torah was the only day when the Jews of Bursztyn allowed themselves to drink and become intoxicated. In the town, it was the happiest day of the year. People danced in the streets. Poor and rich, young and old, would break into a happy round dance and sang. Old Gentiles who had music boxes with canaries and gave concerts in the marketplace, came to the town, allowing themselves to join in the joy and play along. The blind Jewish singer, Mechl, would on that day, sing his entire repertoire.

Not far from Moshe Strickendreier and his wife, Ita, two good, honest people, lived Dovidale the cantor, a prayer leader in the large study house. From the small upkeep that he received there, he was unable to subsist, and had to earn additional [profits] by teaching boys. With him, there were already more adults learning. Notwithstanding his poverty, he was always happy, ready for everyone with an expression [and] a joke.

An important imposing figure in Bursztyn was that of Hersh Schlesinger. During the time of the various upheavals, when Bursztyn went over from one army to another, and not a single Jew could show himself in the street, the Minyan was held at Hersh Schlesinger's home, where the surrounding residents came together to pray, behind nailed down doors. With his dominating aristocratic demeanor, he also affected the other Jews. In his home everyone felt calm, full of belief and hope in better times. He was a big scholar and a beloved activist, ready to come to the aid of every needy individual.

His wife had a store of manufactured goods in the [town] center. In addition to her marketing skills, she also had the virtue of natural modesty and humility. For the men's social activities she demonstrated the warmest understanding.

Meir Walches, a poor Jew, who nonetheless, never stopped conducting himself with the utmost honesty in his relationships with people. He lived on the street that stretched all the way to the Jewish cemetery, in an old, decrepit little house. There, he had a small, compact little shop where the peasants would bring him flax, and he would sell it to other, bigger merchants, leaving for himself the smallest profits, as much as one would give a delivery boy for making a delivery. Nobody ever heard him complain about his impoverishment.

A central personality in the town was David Neuberger, the soul of the Jewish community. Much want and desolateness were alleviated by him. He blotted out many disputes. Everywhere that he got involved, he brought peace and happiness.

Following the First World War, his house became a point of aid for all needy individuals. Aside from the Joint's aid, he, too, gave from his own pockets. He was a big timber merchant and was the first in the town to give his children a secular education. His children were the first students in Bursztyn. But their son, Munye, died before completing his studies. His death broke his parents terribly; they grew indifferent to their own business, which began to go downhill.

But even in the most difficult times, the refined character of the Neubergers did not change. They still retained all their lovely manners, thanks to which their figures remain forever etched in my memory.

Moshe Yosef Tobias was an old Austrian official. In the house where he lived, outside of the city, was the post office; opposite the Ukrainian church, he built for himself prior to the First World War, a four-story house. Following the war, he sold it for Ukrainian money, which, shortly thereafter, lost its value.

[pp. 153-154]

As far as the house was concerned, later on, there were lengthy lawsuits.

Moshe Yosef Tobiases' younger son, Philip, who studied law, was a legionnaire with Pilsudski; later on, a lawyer in Bursztyn, was thoroughly assimilated and had a Christian wife. During the German occupation, he was the representative of the Judenrat.

Organizations and Their Devoted Members

The Right Poalei Tzion, early on in its existence, carried out lively cultural activities among the youth. The I. L. Peretz Library was situated in the building of the Baron Hirsch School. There, courses were organized for those who could not read and write.

|

|

Among the most active were: Yitzchak Landner, Yisroel Leib Fenster, Leib Krochmal, Fishl Schneider, [and] Heller, Nachman Geller's son-in-law. The work that they conducted at the time was exceptionally meaningful. However, it did not last for long. Soon came the fissure, which tore apart this important cultural activity.

In Yisroel Leib Fenster's barber shop, where comrades would get together, Bundist newspapers and proclamations would sometimes appear. In the midst of many youths, there existed a [state of] chaos. The constant arguments disturbed every regulated [form of] work.

The members of the “Hitachdut” Party consisted mostly of well-to-do children. Dr. Besen, a lawyer who was elected a representative in the city council, simultaneously led discussions among the youth, where Zionist problems were discussed.

In 1925, Chaim Ginzburg, the adjudicator's son who had studied in Lemberg, founded “Gordonia.” Following his departure, Yisroel Weiss took over; however, shortly thereafter, he left it [“Gordonia”].

A few people remained behind after the difficult cataclysm, which hit the Jewish people, and as with hundreds of other Jewish towns, Bursztyn was likewise obliterated. Those who had the opportunity to come to Israel, feel the great obligation to write, recall, and tell future generations the history of the destruction of our most beloved and dearest. May these very lines of mine be a brick in the headstone for our town of Bursztyn.

Translator's Footnotes

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Burshtyn, Ukraine

Burshtyn, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2024 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 22 Feb 2024 by LA